Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

1989 Moller

Загружено:

Irfan MohammadАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1989 Moller

Загружено:

Irfan MohammadАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet.

, 1989,30: 123-131

123

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

A study of antenatal care at village level in rural Tanzania

B. Moller*, 0. Lushinod,

0. Meirikb, M. Gebre-Medhin

and G. Lindmark

Apartments of Obstetrics and Gynecology, %cial Medicine and =Pediatrics, Uppsala University, Akademiska Sjukhuset, Uppsala

(Sweden) and *Muga Regional Hmpitai, Iringa (Tanzania)

(Received August 31s~ 1988)

(Revised and accepted November 4th. 1988)

Abstract

Antenatal care is an acknowledged measure for the reduction of maternal and

perinatal mortality. In the rural village of

Ilula, Tanzania, the possible impact of

antenatal care on mortality was studied longitudinally on the basis of the 707 women delivered in the study period. Ninety-five percent

of the antenatal records were available.

Anemia, malaria and anticipated obstetric

problems were the most frequent reasons for

interventions. Among the women from the

area who were delivered in hospital, 90% had

been referred there. No relationship was

found between the number of antenatal visits

and the pregnancy outcome, but perinatal

mortality was correlated to a low birth

weight. Even with a mean attendance rate of

six visits and full coverage by antenatal care

maternal and perinatal mortality remains

high.

Keywords: Prenatal care; Developing country; Health care research; Perinatal mortality;

Twin diagnosis; Breech presentation.

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) emerged in its basic

form 50 years ago in Europe [l]. Although

0020- 7292/ 89/ $03. 50

0 1989 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

Published and Printed in Ireland

this model generally has been adopted in

developing countries, the health problems

noted there are quite different. In Tanzania,

for example, the maternal and child health

(MCH) services operate with limited material

and manpower resources. At a time when the

effectiveness of ANC is being questioned in

European countries by consumers and care

providers alike [2,3], it is prudent to assess the

effectiveness and relevance of various parts of

the ANC part of the MCH organization in

developing countries, including Tanzania.

In 1984 a joint WHO/Tanzanian study on

primary health care [4] reported a mean 95%

registration rate to ANC in seven regions,

with at least one visit to the MCH during

pregnancy. The average number of visits during pregnancy was 4.3, with pronounced

variations between the studied regions. Shears

and Mkerenga [5] analyzed the impact of

mobile MCH services on the maternal health

and pregnancy outcome in several villages of

Tanzania, mainly in the northern part. They

concluded that the MCH services had only

limited influence on the principal problems of

maternal health and nutrition.

The present study analyzes antenatal care

service at the village level in an area where

ANC coverage and attendance are good. It is

based on an evaluation of the actual contents

of the care in terms of detection of complicaClinical and Clinical Research

124

Moller et al.

tions, interventions and patient compliance

relative to pregnancy outcome. To our knowledge such an area-based, prospective study

has not been performed in Tanzania or, for

that matter, in any other developing country.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Between June 1, 1983 to November 30,

1985 all women from the village of Ilula who

delivered at, or attended the antenatal clinic

in Ilula were eligible for enrollment. Of a

total 719 women, 685 were enrolled at a visit

to the antenatal care clinic in Ilula and 34

when they were delivered, shortly after the

study commenced.

The Ilula mission dispensary is staffed by a

village midwife, trained as an MCH aide,

assisted by another MCH aide and the locally

All women

trained

MCH

attendants.

delivered at home (230/o), in the dispensary

(68%) or in the Iringa Regional Hospital

(9Vo) 47 km away. The distance from the

mothers home to the dispensary did not

exceed 6 km for any of the women in the

study population.

Methods

The village midwife undertook the data

collection. She was known by the villagers for

many years, and she knew the women in the

two villages well and enjoyed their respect.

The national antenatal record was used. After

childbirth an extensive questionnaire

was

completed by the midwife during an interview

with the mother. This information served to

validate some data from the antenatal card.

The obstetric history was recorded at the

first antenatal visit. The national Swahili

action-oriented antenatal card [6] has tick

boxes to note risk factors present at

registration or detected at subsequent visits.

When risk factors are present, instructions

adjacent to the boxes explain the nature and

timing of appropriate actions, namely referral

for consultation or for institutional delivery

at a hospital or a health center. Specified risk

Int J Gynecol Obstet 30

factors include previous cesarean section or

poor pregnancy outcome, grand multiparity,

maternal bleeding or hypertensive disorders,

maternal height under 150 cm, fetal malpresentation and post-term pregnancy. The card

also provides separate space for notes on the

dispensing of iron, folic acid and antimalarials. Reasons for referral are noted

and the back of the card is used as the delivery

record. The mothers keep their antenatal card

themselves. The women were instructed to

give the antenatal card to the village midwife

subsequent to delivery or abortion.

The mothers were examined at each visit,

and their weight, blood pressure, any edema,

general health status and the date of their next

visit were noted.

Blood pressure

was

measured in the sitting position with an

aeroid sphygmomanometer.

Complications

and interventions are noted as they occur.

Tetanus

vaccinations

and

prophylactic

medication with iron, folic acid and antimalarial agents are formally parts of the

List of complications during pregnancy divided in

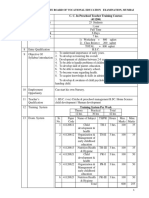

Table I.

symptoms and signs as noted at the 4392 antenatal visits to the

MCH.

No.

of

notes

notes

100

38

10

9

16

34

13

3

3

7

5

14

53

2

18

1

30

10

Symtoms

(a)Abdominal pain, backache, headache,

leg pain

(b) Fever, malaria

General illness, other

Vaginal bleeding

Vaginal discharge, local vaginal disorder

Urinary tract infection, diarrhea

Premature labor, premature rupture of

the membranes

g&W

(c) Anemia, clinicrd diagnosis

Hb<8.5g/lOOml

Pre-eclampsia

Fetal complications: malpresentation.

twinning, fetal distress etc.

Total

20

292

Frenatat care evaluation

Table II.

125

Documented interventions during pregnancy related to length of gestation.

Interventions

Gestational age (weeks)

32-35

Total

Qs of

total

21

28-3 1

Medication (at Ilula dispensary)

Admitted to Hula dispensary

Referrals

For blood transfusion

For consultation of doctor

For hospital admission

For hospital delivery

12

3

10

2

9

4

8

2

3

2

42

13

30

9

2

1

I

3

1

1

2

11

7

2

21

7

5

1

2

18

3

38

18

26

2

27

13

19

Total

18

18

35

43

26

140

100%

program. Fever and general malaise are

regarded as malaria. The diagnosis of anemia

is usually made on clinical impression. Laboratory determination

of hemoglobin most

often was not available.

At the conclusion of the study period,

antenatal cards were scrutinized for notes on

symptoms

and signs, complications

of

pregnancy and interventions.

The information

was coded

and computerized.

Complications were classified in symptoms

and signs, according to Table I. Interventions

were categorized as local interventions or

referrals to hospital (Table II). Referral to a

doctor in the Iringa Regional Hospital for

assessment or admission was a common intervention, either during pregnancy or from the

delivery ward of the dispensary, mostly during labor.

36-39

Data analysis

This analysis is based on the 683 available

antenatal cards, which corresponds to 95% of

the 719 pregnant women enrolled in the

study. The reasons for missing cards were as

follows: six patients had mislaid their cards,

five mothers were lost to follow-up, four

mothers had moved from the area, one

negated antenatal care and 20 cards were lost

in other ways. Judging from other sources of

information, such as the questionnaire, the

log-book and personal communication with

the staff, the utilization of antenatal care in

these groups did not seem to be different

from that of the analyzed population.

Information on hospital deliveries was supplemented with followup information when

the card was not available. Five of the women

with a lost card had hospital deliveries.

Length of gestation at successive visits for all attenders and for attenders divided into two groups according to the

Table III.

number of visits (gw = gestational week).

Length of gestation (weeks) at visit

For all attenders

For women attending five times

or less

For women attending six times

or more

1st gw

Zndgw

3rdgw

4thgw

5thgw

6thgw

7thgw

8thgw

!Jthgw

1Othgw

22

26

30

33

35

36

38

39

40

41

25

29

33

35

31

20

25

29

32

35

36

38

39

40

41

Clinical and Clinical Research

126

Moller et al.

Results

Registration and intervals between visits

The mean

length

of gestation

on

enrollment was 23 weeks, with a range of 634. The number of visits averaged 6.4, with a

range from 1 to 14. Eighty-six percent of the

women had made more than two visits. The

average week of pregnancy for each successive visit is given in Table III. The average

weeks of the visits have been tabulated separately for women with six visits or more and

for those with five visits or fewer. Women

who made five visits or fewer during the span

of pregnancy registered at the ANC clinic in

the 25th week, on average, and delivered at an

average of 38.2 weeks. Half the visits were

made before 33 weeks, and half after.

Clinical findings at antenatal visits

At the 4392 visits by the 685 women, 292

complaints or complications

were noted.

Complaints such as abdominal pain, headache, backache and heaviness without accompanying objective signs were noted in 100

cases, but were not premonitory signs of an

adverse outcome, except in one case of prematurity in week 31. Abdominal pain was

Table IV.

Noted complications related to length of gestation

at diagnosis.

Complications

Fever, general

illness

Vaginal bleeding

Rupture of

membranes

Anemia

Hypertension

Twins, breech

presentation

Total

Gestational age (weeks)

Total

UP

to

28-31

21

32-35

36-39

40

12

3

12

1

10

3

4

1

48

9

8

11

2

9

1

14

53

2

2

21

10

1

12

1

24

41

29

41

31

150

Int J Gynecol Obstet 30

generally poorly defined and might mean discomfort, anxiety or uterine contractions.

Only when accompanied by other symptoms

or signs was it associated with an adverse outcome. The distribution of complications over

time is shown in Table IV.

In addition, 12 women had had a cesarean

section in a previous pregnancy. Seven of

these were delivered in hospital, and four had

a cesarean section delivery this time. Of all

parturients, primigravidae constituted 17%.

Thirteen percent of primigravidae were delivered in the hospital and 71% in the dispensary. Of all pregnant women, 24 (3.4%) were

shorter than 150 cm. Forty percent of the 24

were delivered in hospital.

There were 38 febrile episodes presumed to

be malarial attacks in the antenatal cards, but

at the interview after delivery 171 patients

gave a history of having had malaria during

pregnancy. In this regard, less than a quarter

of malarial attacks were treated at the

antenatal clinic; most patients were treated at

other times at the out-patient department of

the dispensary.

A total of 4240 blood pressure (BP) measurements were made in the study period.

Readings were nearly always recorded to the

nearest multiple of ten. The mean antenatal

pressure was 100/65 mmHg and this did not

vary over pregnancy. Throughout pregnancy

8-10070 of the diastolic readings were 80

mmHg or over, but only 14 readings (0.3%)

were 85 or more. Twenty-nine (0.6%) of the

systolic pressure readings were over 120

mmHg.

Only two patients were referred to hospital

because of an elevated BP reading at a regular

visit. An additional four patients were sent

from the dispensary in labor because of

hypertensive complications. The diastolic BP

at the previous visit to MCH had not

exceeded 80 mmHg for any of the four. However, two of these women had had eclampsia

at the dispensary.

Sixty-four percent of the 58 diagnoses of

anemia were made before the 32nd week, the

majority by inspection of the mucous mem-

Prenatal care evaluation

Hemoglobin values obtained from 152 consecutive

Table V.

antenatal care attenders in Ilula.

Hemoglobin value (g/l)

Readings 070

<85

85-99

100-114

115-129

> 130

33

38

19

branes and not confirmed by laboratory

measurements.

Hemoglobin

values were

checked in a group of patients (n = 152)

participating in concomitant nutritional studies. The distribution of the hemoglobin values

recorded in this group is given in Table V.

Most anemic patients were prescribed

ferrous tablets, generally in inadequate

amounts, as the supplies seldom matched the

demands. Three patients had blood transfusions at the hospital because of anemia

[l] and antepartum hemorrage [2].

Interventions

Interventions resulted from symptoms or

findings. A total of 140 interventions were

documented (Table II). Local interventions

were most commonly medication for malaria,

anemia and other illnesses. Of a total of 95

Table VI.

Hospital deliveries (n = 67, 61 referred, 6 not

referred) and the indications for referral.

Reasons for referral

Referred

From ANC

Malposition, twins, big baby

Previous cesarean section

Anemia

Premature rupture of membranes

Hypertension (2 eclampsia)

Lack of progress in labor

Postmaturity

Local vaginal disorder

Miscellaneous

Unknown

Referred

4

1

6

3

43

referrals, only 85 were actually activated

(Table II). The main indications for referral

to a doctor were pelvic assessment of

primigravidae, twinning, malpositions and

anemia.

Twenty-two of 119 primigravidae

had

pelvic assessment. Of 13 primigravidae 150

cm or under, two had pelvic assessment and

later were delivered by cesarean section at the

hospital. Among 11 remaining short women,

four had normal delivery at home, five delivered at the dispensary, and two delivered at

hospital, one having cesarean section and one

vacuum extraction.

Of all referred patients, 43 delivered in

hospital (Table VI). Another 18 referrals for

hospital delivery were made from the

dispensary of patients in labor. Six of the 67

mothers delivered in hospital had gone there

of their own choice without having been

referred.

Antitetanus vaccination is provided as a

basic immunization for those previously not

vaccinated and as a booster dose for

previously vaccinated women. The coverage

by immunization was 80%. Prophylactic antimalarials and hematinics were provided very

irregularly and clearly not to the extent

intended in the national ANC program.

Twins, breech presentation

Of the 25 twin pregnancies (Table VII), 16

were correctly suspected or diagnosed at an

Table VII.

Twins and breech presentations.

In labor

14

6

5

2

2

1

2

18

127

Correctly diagnosed in

antenatal clinic (olo)

Diagnoses at delivery (olo)

Hospital delivery (Vo)

Birth weight < 2000 g

Mean birth weight (g)

Perinatal mortality rate (Vo)

Twin

pregnancies

(n = 25)

Breech

presentations

(n = 17)

64

36

20

15

21m

28 (14150)

47

53

53

3

2635

53 (9/17)

*Birthweight was known for 44 twins and 12 breech-delivered

infants.

Clinical and Clinical Research

128

Moller ef al.

Table VIII.

Number of antenatal visits in relation to

pregnancy outcome. The table is based on the 683 women for

whom an antenatal card was available (PMR = perinatal mortality rate).

Visits

l-2

No. of patients

Abortions

Deliveries

Mean gestational age at

delivery (weeks)

Birth weight < 2000 g

Mean birth weight (g)

Perinatal deaths

PMR/lOOO

41

7

34

3-4

126

3

123

5-6

187

0

187

>6

329

0

329

Total

6.4

(mean)

683

10

673

37

38

39

40

39.4

8

8

5

0

21

2492 2877 2958 3195 3011

9

9

12

12

42

260

73

64

37

63

average gestational age of 31 weeks. Five

mothers had an X-ray to confirm the diagnosis. Of the 16 women with twin pregnancies

diagnosed antepartum, six delivered at home,

and five (20%) were sent to the referral hospital.

Breech presentation was correctly diagnosed in 8 of 17 cases. Five of these 8 women

had hospital delivery. Because four women

with undiagnosed breech presentation were

referred to hospital for other reasons and

delivered there, nine of the 17 breech presentations (53%) were delivered in hospital.

Number of visits andpregnancy outcome

The outcome related to the numbers of visits is shown in Table VIII. As half of the visits

took place before 33 weeks and subsequent

visits were more closely spaced, women with

premature deliveries had fewer visits. The

high perinatal mortality rate in the low birth

weight groups occurred in women with few

visits. Eight of the nine perinatal deaths in the

group with one or two visits to the ANC clinic

occurred in babies with a birth weight below

2000 g. Evidently the high mortality in the

groups with few visits was associated with a

low birth weight and prematurity.

There were four maternal deaths in this

study. They all occurred in term deliveries

Int J Gynecol Obstet 30

around the time of delivery. In no case could

the outcome

be linked to insufficient

antenatal care, nor was any abnormality

noted during pregnancy.

Discussion

Many components of antenatal care, especially health education and social support, are

difficult to evaluate. In contrast, other

components such as the correct diagnosis of

breech presentation

and twins, site of

delivery, referral patterns and the numbers of

antenatal visits can easily be quantitated. The

Tanzanian national antenatal card [6] was

designed as an instrument to help reduce

maternal and perinatal deaths. This study

demonstrates its additional use for health

service research. Ninety-five per cent of the

cards were available for analysis in this study,

compared with 87% in a similar study in

Aberdeen [7].

Clinical findings at antenatal visits

Some complication or complaint was noted

in 7% (292/4392) of antenatal visits. One

third

concerned

mainly

physiological

inconveniences of pregnancy of no clinical

importance (Table IIa), usually eliciting no

action other than possibly short courses of

symptomatic medication. In general, staff of

busy clinics in many countries pay little heed

to these problems

[3] although

it is

important for the women to be treated with

sympathy in this respect. In 107 instances,

however, symptomatic complications

were

noted (Table IIb). These conditions led the

patient to seek medical care even though a

visit was not scheduled. Eighty-five women

(Table 11~)had a diagnosis of generally symptomless conditions,

mainly

anemia

or

abnormal presentation detected through the

routine monitoring of pregnancy.

Unfortunately

clinical examination does

not always lead to identification of multifetal

pregnancy

or breech presentation.

For

example, the frequency of correct twin

diagnosis in antenatal care was 60% in Swe-

Prenatal care evaluation

den in 1971 [8], before ultrasound or biochemical indicators were used routinely,

suggesting that the 64% detection rate of

twins in Ilula is the rate that can be attained in

routine clinical work without the use of

sophisticated techniques. The breech detection rate of 47% is comparable to the

61% detection rate of term breeches in San

Francisco between 1976 and 1984 [9].

Considering that some breech deliveries in

Ilula were preterm, this detection rate is

reasonable. The value of prelabor diagnosis is

particularly great in view of the perinatal

mortality of 50% and the skill required to

handle breech and multifetal deliveries in the

best of circumstances. As this skill generally is

available only at institutions, patients with

breech presentation or multifetal pregnancy

should be made aware of the importance of

institutional delivery.

Antenatal referrals

Only every fifth primigravida was sent to a

medical officer for pelvic assessment, and

only two of the 13 short primigravidae were

assessed. That all but one of the assessed

women

also had institutional

delivery

probably better indicates that these women

were prone to comply with staff recommendations

than that they were especially at risk. The majority of primigravidae

did not have pelvic assessment, and its value

as part of antenatal monitoring of pregnancy

must be questionned.

Medical actions at the MCH clinic

The prophylaxis and treatment of anemia

and malaria are important ingredients of

ANC. Most febrile illnesses are considered to

be malaria and treated accordingly without

examination. Three quarters of all febrile episodes occurred outside scheduled visits to the

MCH and were treated elsewhere. When

defined according

to WHO (< lOOg/l),

anemia was found to be present in 14 women,

or 10% of the sample. This frequency is considerably lower than the 45% reported from

Mozambique [lo] and the 20% from the

129

Ivory Coast [ 111. Although the diagnosis of

anemia by clinical inspection is inaccurate

[12], laboratory confirmation is often not

feasible. The use of prophylactic medication

by all pregnant women or at least those displaying signs of anemia, should constitute a

more important part of antenatal care than

was seen here.

Weight and blood pressure recordings

A considerable amount of time and effort

is spent on recording the body weight and

blood pressure of every expectant mother at

each visit. Maternal weight and its relation to

birth weight will be reported elsewhere [ 131.

In routine clinical work, the findings at

weighing mothers at each visit rarely alter

their management, and this practise was even

discarded by Essex et al. [6].

The yield of blood pressure measurements

was particularly low. Ilula is an area with a

relatively low rate of eclampsia. The two

cases of eclampsia were not detected in the

pre-eclamptic

stage. The remaining

few

hypertensive patients were identified through

concomitant or incidental clinical symptoms

rather than by blood pressure recordings. The

detection rate might be increased, with less

waste of time, by performing blood pressure

recordings at each visit only in risk groups,

namely primigravidae, women with previous

pregnancy hypertension and those with a high

blood pressure at the first visit. Tests for

albuminuria in these cases should be given

priority, and when diagnostic tools are scarce,

they should be saved for these cases.

Prophylactic medication

One of the stated purposes of antenatal

care is to provide prophylactic medication for

the prevention of some complications such as

anemia and malaria. Also, neonatal tetanus is

prevented by maternal immunization. Logistic problems make this part of ANC vulnerable and insufficient [14]. Of medications and

vaccinations, only the antitetanus vaccination

program worked fairly well, while hematinics

and anti-malarial agents very often were not

Clinical and Clinical Research

130

Moller et al.

available. This important goal of the national

preventive program has not nearly been

reached.

Number and timing of antenatal visits

Several reports [15-171 show a correlation

between frequent attendance at an antenatal

clinic and a good pregnancy outcome.

However, these studies suffer from two major

weaknesses. One is the problem of self-selection by mothers registering for antenatal care,

and the other is that the quality of the care is

not assessed [ 181. In most European countries

a full antenatal program comprises lo-12

visits. The recommendations for the spacing

of visits vary considerably, however, but

according to Blonde1 [19] outcome as measured in national perinatal mortality is not

related to the number of antenatal visits.

In this study we found an association

between the outcome of pregnancy and the

number of antenatal visits. We question,

however, the causality of this association. If

the preterm and low birth weight babies with

their high mortality are taken into account,

an independent effect of the number of

antenatal visits is no longer obvious. Unfortunately, prematurity and low birth weight

are usually not preventable through antenatal

care other than possibly by treating malarial

episodes and other infections.

Early enrollment for antenatal care has

long been encouraged. The purpose of this

early attendance is to permit the detection and

treatment of maternal diseases such as anemia, syphilis and tuberculosis and to allow a

better dating of pregnancy. Unless screening

for these conditions is actually practised, the

justification of early enrollment fails.

Structured programs

To improve results within the framework

of programs with limited resources, greater

emphasis should be placed on quality rather

than on quantity in antenatal care. Structured

programs based on local priorities ideally

should optimize the use of scarce resources.

In her account of the setting in Scotland, Hall

Int J Gynecol Obstet 30

[2] suggests a reduction in the number of

planned visits for normal multigravidae to

four. Primigravidae should be followed up

according to the traditional

programme

because of their higher risk of hypertensive

disorders.

In the case of Tanzania, programs may be

worked out along the same goal-oriented

lines. A few visits will be enough to detect

most risk factors. Some women with risk

factors will need closer monitoring.

All

women

should

be advised

to report

immediately should complications such as

bleeding occur. Most gravidae will benefit

from a program in which the aim of all

scheduled visits is defined and clearly stated.

Improved attention to individual and group

instruction, especially of women at high risk

such as women with multifetal pregnancies

and breech presentations,

should assist in

improving pregnancy outcome. To increase

compliance, women should be made aware of

their personal risk factors [20].

The present organization of MCH clinics in

Tanzania is such that women bring their

children and all parties receive regular health

education. Visitors to MCH clinics have been

found to be very receptive audiences [5]. An

appropriately compiled collection of centrally

prepared short health education programs

will help the MCH staff in this task [21].

Limits of antenatal care

In this study, the main causes of perinatal

death were prematurity and LBW births. In

the absence of resources for referral to a hospital and/or of an effective preventive medication program, one can speculate if perinatal

mortality rates can be lowered by significantly

more frequent routine antenatal visits.

Other determinants of pregnancy outcome

clearly are present. Social factors such as

female work load and nutrition, from childhood onwards, also influence the outcome of

pregnancy and probably are just as important

as those risk factors that might be mitigated

by specific actions taken in antenatal care.

In conclusion, our assessment of the effec-

Prenatal care evaluation

tiveness of the antenatal services in a rural

setting in Tanzania has shown that despite

good coverage of the pregnant population by

a popular antenatal service, maternal and

perinatal mortality rates remain high, apparently not affected by the frequent antenatal

monitoring. One probable reason for this is

that perinatal mortality is largely associated

with prematurity and low birth weight, both

of which cannot be easily influenced simply

by checking mothers for risk factors.

On the other hand, the present system

of

antenatal

care

provides

excellent

opportunities to reach mothers with prophylactic medication, vaccinations, and diagnosis

and treatment of infectious diseases, and also

health education programs.

The present study suggests that more

emphasis should be placed on preventive

medical and social measures. Strengthening

of the referral capacity is also a necessity if

obstetric risk screening is to be made

worthwhile.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by SAREC grant

81/79. We are indebted

to UNICEF,

Tanzania, for logistical support.

References

Wagner MG: Health services for pregnancy care in

Europe. Int J Technol Assess Health Care I: 789,1985.

Hall M: Antenatal care in practice. Spastics Int Med Public, London, 1982.

Garcia JO: Womens views of antenatal care. Spastics Int

Med Public, London, 1982.

Government of Tanzania/UNICEF:

An analysis of the

situation of women and children. Dar Es Salaam, 1985.

Shears F, Mkerenga R: Evaluating the impact of mother

and child health (MCH) services at village level, a survey

in Tanzania, and lessons for elsewhere. Ann Trop Pediatr

5: 55.1985.

131

6 Essex BJ, Everett J: Use of an action oriented record for

antenatal screening. Trop Dot 7: 134.1977.

7 Hall MH, Chng PK, MacGillivray I: Is routine antenatal

care worth while? Lancet ii: 78, 1980.

8 Grennert L, Persson PH, Gennser G, Kullander S:

Ultrasound and human placental-lactogcn

for early

detection of twin pregnancies. Lancet i: 4, 1976.

9 Flanagan TA, Mulchahey KM, Korenbrot CC, Green JR,

Laros KL: Management of term breech presentation. Am

J Obstet GynecolZ56: 1492,1987.

10 Boatin BA, Bulsara MK. Wurpa FK: Evaluation of

conjunctival pallor in the diagnosis of anaemia. J Trop

Med Hyg89: 33.1986.

11 Reinhart MC: A survey of mothers and their newborns in

Abijan, Ivory Coast. Helv Paediatr Acta Suppl 41, 33:

1978.

12 Wurapa FK, Bulsara MK, Boatin SA: Evaluation of conjunctival pallor in the diagnosis of anemia. J Trop Med

Hyg 89: 33,1986.

13 Moller BJ, Gebre-Medhin M, Lindmark G: Maternal

weight, weight gain and birth weight at term in the rural

Tanzanian village of Ilula. Br J Obstet Gynecol, in press.

14 Ministry of Health: Report on a study on patient

management, essential drugs and equipment supply. Tanzania, 1985.

15 Ryan GM: Prenatal care and pregnancy outcome. Am J

Obstet Gynecol137: 876. 1980.

16 Gorthmaker S: The effects of prenatal care upon the

health of the newborn. Am J Public Health 69: 653, 1979.

17 Greenberg R: The impact of prenatal care in different

social groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol145: 797,1982.

18 Helliger FJ: Prenatal care, neonatal intensive care and

infant mortality. J Technol Assess Health Care I: 934,

1985.

19 Blonde1 B: Some characteristics of antenatal care in 13

European countries. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 92: 565,1985.

20 WHO/UNICEF Joint Statement: Maternal care for the

reduction of perinatal and neonatal mortality. WHO,

Geneva, 1986.

21 Morley D: Communication and learning. In Pediatric

Priorities in Developing Countries, p 3%. Butterworth,

London, 1975.

Address for reprints:

G. Ltodmark

Dejnutment of Obstetrks and Gynecology

tJPplul8univemity

AludemisluS]nkbnset

s 75185 Sweden

Clinical and Clinical Research

Вам также может понравиться

- Jurnal GH TambuntaДокумент6 страницJurnal GH TambuntaIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Dia Care-2015-Huang-746-51 PDFДокумент6 страницDia Care-2015-Huang-746-51 PDFMohammad IrfanОценок пока нет

- Antibiotic Treatment Strategies For Community Acquired Pneumonia in AdultsДокумент12 страницAntibiotic Treatment Strategies For Community Acquired Pneumonia in AdultsCumbelia PrimaОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Metabolism: Departemen Fisiologi Fakultas Kedokteran USUДокумент22 страницыIntroduction To Metabolism: Departemen Fisiologi Fakultas Kedokteran USUAnditha Namira RSОценок пока нет

- Managing Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura: An UpdateДокумент7 страницManaging Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura: An UpdateApriliza RalasatiОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis and Management of Clinical ChorioamnionitisДокумент18 страницDiagnosis and Management of Clinical ChorioamnionitisIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Itp Periop1Документ4 страницыItp Periop1Irfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Dia Care 2015 Krul Poel 1420 6Документ7 страницDia Care 2015 Krul Poel 1420 6Irfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- K 19 20 Metabolism RegulationДокумент29 страницK 19 20 Metabolism RegulationIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Itp Periop1Документ4 страницыItp Periop1Irfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Dia Care 2015 Bellido 2211 6Документ6 страницDia Care 2015 Bellido 2211 6Irfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Dia Care-2015-Siraj-2000-8Документ9 страницDia Care-2015-Siraj-2000-8Irfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- 1994 Al NasserДокумент9 страниц1994 Al NasserIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- CH08 Vaginal Breech DeliveryДокумент25 страницCH08 Vaginal Breech DeliveryShintaPuspitasariОценок пока нет

- Terapi AntiretroviralДокумент13 страницTerapi AntiretroviralthiamuthiaОценок пока нет

- 2005 HildingssonДокумент7 страниц2005 HildingssonIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Normal Newborn CareДокумент49 страницNormal Newborn CareIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- 1987 ReebДокумент7 страниц1987 ReebIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Maternal Anatomy WilliamsДокумент52 страницыMaternal Anatomy WilliamsIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- 1987 ReebДокумент7 страниц1987 ReebIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Dia Care-2015-Zeitler-2285-92Документ8 страницDia Care-2015-Zeitler-2285-92Irfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Dia Care 2015 Bellido 2211 6Документ6 страницDia Care 2015 Bellido 2211 6Irfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- ITP BJH 2003Документ23 страницыITP BJH 2003Mohammad IrfanОценок пока нет

- Antibiotic Treatment Strategies For Community Acquired Pneumonia in AdultsДокумент12 страницAntibiotic Treatment Strategies For Community Acquired Pneumonia in AdultsCumbelia PrimaОценок пока нет

- Guidline EndocarditisДокумент54 страницыGuidline EndocarditisIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- Copd NICE GuidlinesДокумент61 страницаCopd NICE GuidlinesIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- 2007 NiceДокумент249 страниц2007 NiceIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- HipoglikemiaДокумент12 страницHipoglikemiaIrfan MohammadОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- RCPI Diabetes GuidelinesДокумент88 страницRCPI Diabetes GuidelinesJohn Smith100% (1)

- Thesis Statement Opposing AbortionДокумент5 страницThesis Statement Opposing Abortionaflnbwmjhdinys100% (2)

- NCP Pain - OBДокумент5 страницNCP Pain - OBSandra Guimaray50% (2)

- Childbirth Education Then and NowДокумент5 страницChildbirth Education Then and Nowazida90Оценок пока нет

- Maternal Mortality 1-5Документ36 страницMaternal Mortality 1-5Samuel CrewzОценок пока нет

- 2B-C - Why Did Mrs X Died PDFДокумент19 страниц2B-C - Why Did Mrs X Died PDFReyna Chame GarcinezОценок пока нет

- Pre School Teacher Training Course. 1Документ19 страницPre School Teacher Training Course. 1MithileshОценок пока нет

- Safe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGДокумент16 страницSafe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGAryaОценок пока нет

- 05-Insurance Companies Policy-NewДокумент18 страниц05-Insurance Companies Policy-NewIBRAHIM ELSHOURAОценок пока нет

- Stugeron DosageДокумент5 страницStugeron Dosagetarcher1987Оценок пока нет

- Susana O. Pabinguit, B.S.N., R.N. DOH-Central VisayasДокумент58 страницSusana O. Pabinguit, B.S.N., R.N. DOH-Central VisayasRnheals Central Visayas100% (8)

- ANC Guideline PresentationДокумент42 страницыANC Guideline PresentationDeepak BamОценок пока нет

- AEMT - Obstetrics and Pediatrics Exam PracticeДокумент26 страницAEMT - Obstetrics and Pediatrics Exam PracticeEMS DirectorОценок пока нет

- ScizopheniaДокумент20 страницScizopheniaGogea GabrielaОценок пока нет

- Why Antenatal Care is EssentialДокумент4 страницыWhy Antenatal Care is EssentialChennulОценок пока нет

- Nihms 940015Документ50 страницNihms 940015Maria Salome Olortegui AceroОценок пока нет

- Duty Report 5.12.1978Документ55 страницDuty Report 5.12.1978Riyan W. PratamaОценок пока нет

- Lecture 10 - Reproductive SystemДокумент83 страницыLecture 10 - Reproductive SystemNiyanthesh Reddy100% (1)

- Stonecoal v3 Guidelines 2023-06-09Документ77 страницStonecoal v3 Guidelines 2023-06-09Entertainment Buddy'sОценок пока нет

- Determinants of First Antenatal Visit Timing Among Pregnant Women in Antenatal Care at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Western UgandaДокумент19 страницDeterminants of First Antenatal Visit Timing Among Pregnant Women in Antenatal Care at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Western UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONОценок пока нет

- OC Set B NEWДокумент18 страницOC Set B NEWmatrixtrinityОценок пока нет

- Calculation of Concentrate Requirement of A Dairy Cattle On The Basis of FatДокумент4 страницыCalculation of Concentrate Requirement of A Dairy Cattle On The Basis of Fatfarid khan100% (1)

- Assessing Fetal Wellbeing in PregnancyДокумент8 страницAssessing Fetal Wellbeing in PregnancyViviane Ńíáshéè Basod100% (1)

- Sepsis Neonatorum UpdatedДокумент87 страницSepsis Neonatorum Updated'Eduard Laab AlcantaraОценок пока нет

- Rle NST PPT DraftДокумент4 страницыRle NST PPT DraftJingie Leigh EresoОценок пока нет

- Prenatal Chart 2022Документ3 страницыPrenatal Chart 2022Dheeraj ChopadaОценок пока нет

- Midwifery and ObstetricsДокумент16 страницMidwifery and ObstetricsOdette Wayne BalatbatОценок пока нет

- Abortion Case StudyДокумент18 страницAbortion Case StudyJuan Miguel T. Magdangal33% (3)

- Sss Gsis LawДокумент57 страницSss Gsis LawBroy D Brium100% (1)

- Rheumatological Disorders in PregnancyДокумент61 страницаRheumatological Disorders in Pregnancydrsyan hamzahОценок пока нет