Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Media Law - Freedom of The Press: ALADS v. Los Angeles Times (2015) - First Amendment - Prior Restraint - Anti-SLAPP - Constitutional Law

Загружено:

California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

123 просмотров11 страниц"In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy.

The press was to serve the governed, not the governors."

(New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) 403 U.S. 713, 717 [29 L. Ed. 2d 822, 91 S. Ct. 2140] (New York Times.) "[P]rior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on

First Amendment rights." (Nebraska Press Assn. v. Stuart (1976) 427 U.S. 539, 559 [49 L.Ed.2d 683, 96 S.Ct.

2791] (Nebraska Press).) "The damage can be particularly great when the prior restraint falls upon the communication of news and commentary on current events."

For independent investigative reporting, news, analysis and opinion about the California Judicial Branch:

California Judicial Branch News Service www.cjbns.org

Supreme Court of California Report: www.californiasupremecourtnews.blogspot.com

Judicial Council Watcher: www.judicialcouncilwatcher.com

Judicial Council of California Report: www.californiajudicialcouncil.blogspot.com

Commission on Judicial Performance Report: www.cjpnews.blogspot.com

Center for Judicial Excellence: www.centerforjudicialexcellence.org

California Superior Courts Report: www.californiasuperiorcourts.blogspot.com

California Courts of Appeal Report: www.californiaappellatecourts.blogspot.com

California Federal Courts Report: www.federalcourtnews.blogspot.com

State Bar of California Report: www.statebarnews.blogspot.com

California Law Enforcement Report: www.lawenforcementreport.blogspot.com

Sacramento Family Court Report: www.sacramentocountyfamilycourtnews.blogspot.com

Third District Court of Appeal Report: www.thirddistrictcourtofappealnews.blogspot.com

California State Auditor Report: www.stateauditornews.blogspot.com

Sacramento Superior Court Report: www.sacramentosuperiorcourt.blogspot.com

Оригинальное название

Media Law - Freedom of the Press: ALADS v. Los Angeles Times (2015) - First Amendment - Prior Restraint - Anti-SLAPP - Constitutional Law

Авторское право

© Public Domain

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документ"In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy.

The press was to serve the governed, not the governors."

(New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) 403 U.S. 713, 717 [29 L. Ed. 2d 822, 91 S. Ct. 2140] (New York Times.) "[P]rior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on

First Amendment rights." (Nebraska Press Assn. v. Stuart (1976) 427 U.S. 539, 559 [49 L.Ed.2d 683, 96 S.Ct.

2791] (Nebraska Press).) "The damage can be particularly great when the prior restraint falls upon the communication of news and commentary on current events."

For independent investigative reporting, news, analysis and opinion about the California Judicial Branch:

California Judicial Branch News Service www.cjbns.org

Supreme Court of California Report: www.californiasupremecourtnews.blogspot.com

Judicial Council Watcher: www.judicialcouncilwatcher.com

Judicial Council of California Report: www.californiajudicialcouncil.blogspot.com

Commission on Judicial Performance Report: www.cjpnews.blogspot.com

Center for Judicial Excellence: www.centerforjudicialexcellence.org

California Superior Courts Report: www.californiasuperiorcourts.blogspot.com

California Courts of Appeal Report: www.californiaappellatecourts.blogspot.com

California Federal Courts Report: www.federalcourtnews.blogspot.com

State Bar of California Report: www.statebarnews.blogspot.com

California Law Enforcement Report: www.lawenforcementreport.blogspot.com

Sacramento Family Court Report: www.sacramentocountyfamilycourtnews.blogspot.com

Third District Court of Appeal Report: www.thirddistrictcourtofappealnews.blogspot.com

California State Auditor Report: www.stateauditornews.blogspot.com

Sacramento Superior Court Report: www.sacramentosuperiorcourt.blogspot.com

Авторское право:

Public Domain

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

123 просмотров11 страницMedia Law - Freedom of The Press: ALADS v. Los Angeles Times (2015) - First Amendment - Prior Restraint - Anti-SLAPP - Constitutional Law

Загружено:

California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas"In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy.

The press was to serve the governed, not the governors."

(New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) 403 U.S. 713, 717 [29 L. Ed. 2d 822, 91 S. Ct. 2140] (New York Times.) "[P]rior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on

First Amendment rights." (Nebraska Press Assn. v. Stuart (1976) 427 U.S. 539, 559 [49 L.Ed.2d 683, 96 S.Ct.

2791] (Nebraska Press).) "The damage can be particularly great when the prior restraint falls upon the communication of news and commentary on current events."

For independent investigative reporting, news, analysis and opinion about the California Judicial Branch:

California Judicial Branch News Service www.cjbns.org

Supreme Court of California Report: www.californiasupremecourtnews.blogspot.com

Judicial Council Watcher: www.judicialcouncilwatcher.com

Judicial Council of California Report: www.californiajudicialcouncil.blogspot.com

Commission on Judicial Performance Report: www.cjpnews.blogspot.com

Center for Judicial Excellence: www.centerforjudicialexcellence.org

California Superior Courts Report: www.californiasuperiorcourts.blogspot.com

California Courts of Appeal Report: www.californiaappellatecourts.blogspot.com

California Federal Courts Report: www.federalcourtnews.blogspot.com

State Bar of California Report: www.statebarnews.blogspot.com

California Law Enforcement Report: www.lawenforcementreport.blogspot.com

Sacramento Family Court Report: www.sacramentocountyfamilycourtnews.blogspot.com

Third District Court of Appeal Report: www.thirddistrictcourtofappealnews.blogspot.com

California State Auditor Report: www.stateauditornews.blogspot.com

Sacramento Superior Court Report: www.sacramentosuperiorcourt.blogspot.com

Авторское право:

Public Domain

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 11

Page 1

1 of 1 DOCUMENT

Positive

As of: Apr 17, 2016

ASSOCIATION FOR LOS ANGELES DEPUTY SHERIFFS et al., Plaintiffs and

Appellants, v. LOS ANGELES TIMES COMMUNICATIONS LLC, Defendant and

Respondent.

B253083

COURT OF APPEAL OF CALIFORNIA, SECOND APPELLATE DISTRICT,

DIVISION THREE

239 Cal. App. 4th 808; 191 Cal. Rptr. 3d 564; 2015 Cal. App. LEXIS 717; 43 Media L.

Rep. 2326

July 21, 2015, Opinion Filed

SUBSEQUENT HISTORY: The Publication Status of

this Document has been Changed by the Court from

Unpublished to Published August 19, 2015.

Time for Granting or Denying Review Extended

Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs v. Los

Angeles Times Communications LLC, 2015 Cal. LEXIS

8973 (Cal., Oct. 27, 2015)

Review denied by Ass'n for L.A. Deputy Sheriffs v. L.A.

Times Communs. Llc, 2015 Cal. LEXIS 9542 (Cal., Nov.

18, 2015)

PRIOR-HISTORY:

APPEAL from an order of the

Superior Court of Los Angeles County, No. BC520745,

Michelle R. Rosenblatt, Judge.

HEADNOTES-1

Sheriffs' Employment Records--Anti-SLAPP Motion

to Strike.--It was proper under Code Civ. Proc.,

425.16, the anti-SLAPP (strategic lawsuit against public

participation) statute, to strike a complaint by unnamed

deputy sheriffs and their union that sought to enjoin a

newspaper from publishing reports about the hiring and

evaluation of deputies, including allegations of past

misconduct. Of all the constitutional imperatives

protecting a free press under U.S. Const., 1st Amend., the

most significant is the restriction against prior restraint

upon publication.

[Cal. Forms of Pleading and Practice (2015) ch. 303,

Injunctions, 303.71; 5 Witkin, Cal. Procedure (5th ed.

2008) Pleading, 1030; 5 Witkin, Summary of Cal. Law

(10th ed. 2005) Torts, 651; 7 Witkin, Summary of Cal.

Law (10th ed. 2005) Constitutional Law, 363.]

CALIFORNIA OFFICIAL REPORTS HEADNOTES

(7) Constitutional Law 57--Freedom of Press--Prior

Restraint--Newspapers--Publication of Deputy

COUNSEL: Green & Shinee, Elizabeth J. Gibbons;

Benedon & Serlin, Gerald M. Serlin and Kelly R.

CALIFORNIA JUDICIAL BRANCH NEWS SERVICE

CJBNS.ORG

Page 2

Horwitz for Plaintiffs and Appellants.

FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

Davis Wright Tremaine, Kelli L. Sager, Rochelle L.

Wilcox, Daniel A. Laidman; and Jeffrey D. Glasser for

Defendant and Respondent.

1. The Office of Public Safety and the Los Angeles

County Sheriff's Department

JUDGES: Opinion by Egerton, J.,* with Kitching,

Acting P. J., and Aldrich, J., concurring.

*

Judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court,

assigned by the Chief Justice pursuant to article

VI, section 6 of the California Constitution.

According to appellants, the Los Angeles County

Office of Public Safety (OPS) used to be a law

enforcement agency separate from the Los Angeles

County Sheriff's Department (LASD). In 2010, the

county decided to merge OPS into LASD. Apparently,

OPS officers who wanted to work for LASD were

required to complete application forms for LASD. LASD

hired former OPS officers to work as deputy sheriffs.

OPINION BY: Egerton, J.

OPINION

EGERTON, J.*--"In the First Amendment the

Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it

must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy.

The press was to serve the governed, not the governors."

(New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) 403 U.S.

713, 717 [29 L. Ed. 2d 822, 91 S. Ct. 2140] (New York

Times.) "[P]rior restraints on speech and publication are

the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on

First Amendment rights." (Nebraska Press Assn. v. Stuart

(1976) 427 U.S. 539, 559 [49 L.Ed.2d 683, 96 S.Ct.

2791] (Nebraska Press).) "The damage can be

particularly great when the prior restraint falls upon the

communication of news and commentary on current

events." (Ibid.)

In this case, the union representing deputy sheriffs in

the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department sued to

enjoin the Los Angeles Times from publishing news

reports about the department's hiring of officers who used

to work for the county's office of public safety. The union

alleged that a Times reporter had documents and

information from the applications and background checks

on the deputies. The trial court granted the Times's

anti-SLAPP motion.1 The union and unnamed Doe

plaintiffs appeal. We affirm.

*

Judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court,

assigned by the Chief Justice pursuant to article

VI, section 6 of the California Constitution.

1 A SLAPP is a strategic lawsuit against public

participation. A defendant facing such a lawsuit

may file a special motion to strike the complaint.

(Code Civ. Proc., 425.16.)

The LASD application form is 17 pages long. The

form asks for (among other things) the names and

addresses of family members, previous employment,

military service, educational background, current debts,

monthly income and expenditures, and references. The

application form also requires applicants to state whether

they have ever been fired from a job or reprimanded at

work, expelled or suspended from school, court-martialed

or otherwise disciplined by the military, arrested as a

juvenile or adult, been the subject of a call to police, or

had their driver's license suspended or revoked.

The form does not say that the information the

applicant provides will be kept in confidence. Applicants

also are required to sign an "Information Waiver"

authorizing others to release "confidential and privilege

[sic]" information to LASD "[f]or [the] specific purpose"

of LASD's consideration of the application. At least as of

September 2013, LASD "assured" the applicant "of the

confidential nature of his application and that it will not

be divulged." It was the "understanding" of at least one

deputy who joined LASD from OPS in June 2010 "when

[he] submitted [his] application and the supporting

documentation that all this information would be

maintained by the Sheriff's Department as confidential."

At least as of September 2013, LASD's practice was to

contact all five references an applicant listed and to ask,

for example, about the applicant's temperament, drinking

habits, and drug use. At least as of September 2013,

LASD's practice was "to provide assurances to these

references that their names and comments will be held in

strict confidence."

In July 2013 two LASD deputies who had worked

for OPS received telephone calls from a man who

identified himself as Robert Faturechi, a reporter for the

Los Angeles Times. Faturechi told one deputy that he had

Page 3

a copy of the deputy's "complete background

investigation file," and that he had obtained "several

other deputies' background files ... from a source within

the Department." That deputy agreed to meet with

Faturechi. Faturechi asked the second deputy about his

disciplinary record when he worked for OPS. Faturechi

told both deputies that he was writing an article for the

Times about LASD's hiring of former OPS deputies.

2. The Complaint and Application for Injunctive Relief

On September 10, 2013, the union representing

deputy sheriffs in LASD--the Association for Los

Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (ALADS)--filed a complaint

and an ex parte application for a temporary restraining

order and order to show cause, seeking preliminary and

permanent injunctions. The complaint also listed as

plaintiffs "Deputy John Doe[s]" 1 through 13, "Deputy

Jane Doe-1," and "500 Similarly Situated ALADS

Members." The complaint named as defendants Robert

Faturechi, a Los Angeles Times reporter,2 and Los

Angeles Times Communications LLC.

2

ALADS never served Faturechi with the

summons and complaint, and he never appeared

in the action.

ALADS alleged a single cause of action entitled:

"CAUSE OF ACTION for Temporary Restraining Order,

Preliminary Injunction, Permanent Injunction Preventing

Release of Confidential Personnel, Education, Medical

and Credit Information." ALADS alleged that, in

applying for employment with LASD, the former OPS

officers were required to provide a substantial amount of

confidential and private information. ALADS also

alleged that background checks for the applicants

involved "interview statements," and that LASD's

"practice" was "to promise, and provide, confidentiality

to the people making these statements in order to obtain

the fullest, most complete, and most can did statements

concerning the applicant as possible." ALADS alleged

that "[a]t some unknown time prior to August, 2013,

Defendant Faturechi stole, received from someone else

who stole, or otherwise unlawfully came into physical

possession of the confidential background investigation

files of Deputy John Doe and approximately 500 other

County peace officers who are similarly situated to

Deputy Doe." ALADS alleged Faturechi had contacted

some of the OPS/LASD deputies to ask them questions.

ALADS prayed for an injunction barring the Times

from "[r]eleasing or publishing, in print, on line, or in any

other media or format, to the public" any information

"obtained from or contained in the background

investigation files," including the deputies' names,

photographs, and "[a]ny non-public criminal history."

ALADS also sought a court order requiring the Times "to

immediately return" to LASD3 "each and every copy of

every Sheriff's Department background investigation file

[that] were [sic] unlawfully obtained by Defendants [sic]

Faturechi."

3 The LASD has never been a party to this

action.

A hearing on ALADS's ex parte application for a

temporary restraining order and order to show cause

apparently was held on September 10, 2013, in a writs

department.4 The trial court denied ALADS's application.

The court noted the Doe declarations ALADS submitted

"contain no personal details about the declarants that

would relieve them of the obligation of identifying

themselves, particularly when the declarations contain the

hearsay statement of defendant Faturechi concerning

when the article is going to be published and what it will

contain--the evidence most critical to the showing of

irreparable harm or immediate danger that plaintiff must

make to justify ex parte relief." The court also observed,

"The declarations are also very vague in their reference to

the personal information that Faturechi told the declarants

he would be publishing." The court "decline[d] to issue a

TRO imposing a prior restraint on defendants' free speech

based on the speculative hearsay testimony of anonymous

witnesses."

4

ALADS has not submitted a reporter's

transcript of that proceeding.

The court denied the application on the additional

ground that ALADS--by its own admission--had known

for weeks if not months that the Times had information

from the OPS/LASD deputies' files, that notwithstanding

this knowledge it had not proceeded by noticed motion,

and therefore that "any exigency appear[ed] to be of

[ALADS's] own making."

3. The Times's Anti-SLAPP Motion and the Trial Court's

Ruling

The case was assigned to a calendar and trial court.

The Times filed an anti-SLAPP motion, arguing that the

injunction ALADS sought would be an unconstitutional

CALIFORNIA JUDICIAL BRANCH NEWS SERVICE

CJBNS.ORG

Page 4

prior restraint. ALADS filed opposition. ALADS argued

that the court should delay ruling on the motion until it

could depose Faturechi, that the SLAPP statute did not

apply because Faturechi's possession of the files was

"illegal as a matter of law," that ALADS had shown a

probability of prevailing on its claim, and that the

injunctive relief it sought was not a prior restraint

because it was not "content-based." ALADS submitted

declarations from two deputy sheriffs doing background

checks in the personnel bureau, two deputy sheriffs

identified only as John Does 3 and 14,5 a man who owns

a company that helps "law enforcement officers and their

families in removing private and personal information

from the Internet," and a sergeant who was

"investigat[ing] the theft" of the files. The Times filed

evidentiary objections to parts of the declarations.

5 The complaint does not list as a plaintiff a

John Doe 14.

The trial court held a hearing on the special motion

to strike on October 9, 2013. The court sustained many of

the Times's evidentiary objections to ALADS's

declarations and overruled others. At the conclusion of

the hearing the court granted the motion. The court first

noted that the SLAPP statute generally stays discovery

absent a noticed motion showing good cause. The court

agreed with the Times that "the qualifications, conduct,

and identities of peace officers are matters of public

interest," citing Gomes v. Fried (1982) 136 Cal.App.3d

924, 933 [186 Cal. Rptr. 605] ("'law enforcement is a

primary function of local government'" and the public has

a great "'interest in the qualifications and conduct of law

enforcement officers'" (italics omitted)). The trial court

also stated that ALADS had not "provide[d] any evidence

that Faturechi's possession or acquisition of the

background investigations is illegal/criminal." The court

observed the cases ALADS cited were distinguishable:

"they were situations where illegality was either

conceded by the Defendant or where Plaintiffs' evidence

established illegal conduct." The court acknowledged the

"wealth of both State and Federal case law" finding First

Amendment protection for journalists who "did not

[themselves] engage in the illegal conduct but had reason

to know the information they had received had been

obtained illegally in the first instance."

As for the probability of success on the merits, the

trial court stated ALADS had "not adequately alleged any

underlying privacy cause of action," instead pleading

only "a single cause of action seeking injunctive relief."

The court observed ALADS had "not provided any

admissible evidence identifying what, if any, confidential

documents [the Times] has i[n] its possession." The court

concluded the injunction ALADS sought would be "a

prior restraint of speech." As for ALADS's request for a

court order requiring the Times and Faturechi to turn files

over to LASD, the court stated ALADS had not alleged

any "separate cause of action for conversion or any

comparable claim" nor had it or the Doe plaintiffs

"identified their ownership rights to [the] property."

Finally, with respect to ALADS's delay, the trial court

cited evidence the Times had submitted showing the

Times "began reporting on the Sheriff's Department's

deficiencies in hiring" in October 2012.

ALADS timely appealed.6

6 The Times states in its brief that it published

an article on December 1, 2013, reporting that

LASD had hired "dozens" of OPS deputies even

though their background investigations "raised

serious concerns about dishonesty and

misconduct," and that the county board of

supervisors then asked LASD to investigate. The

Times has not complied with rule 8.252 of the

California Rules of Court, governing requests for

judicial notice.

APPELLANTS' CONTENTIONS

ALADS contends the Times is not entitled to invoke

the anti-SLAPP statute because its possession of the

deputies' "confidential personnel files" is "clearly illegal."

ALADS also asserts the trial court erred in sustaining

evidentiary objections to parts of the declarations

ALADS submitted. ALADS argues that, even though it

termed its cause of action "one for injunctive relief," its

factual allegations add up to a claim for invasion of the

"primary right of privacy." Finally, ALADS contends--as

it did in the trial court--that the injunction it seeks is not

a prior restraint because it is not "content-based."

DISCUSSION

We review the trial court's evidentiary rulings for

abuse of discretion. (Molenda v. Department of Motor

Vehicles (2009) 172 Cal.App.4th 974, 986 [91 Cal. Rptr.

3d 792].) We review the court's grant of the anti-SLAPP

motion de novo and independently determine whether the

parties have met their respective burdens. (Cross v.

Page 5

Cooper (2011) 197 Cal.App.4th 357, 371 [127 Cal. Rptr.

3d 903] (Cross); Soukup v. Law Offices of Herbert Hafif

(2006) 39 Cal.4th 260, 269, fn. 3 [46 Cal. Rptr. 3d 638,

139 P.3d 30] (Soukup).) We do not weigh credibility or

compare the weight of the evidence. (Cross, supra, 197

Cal.App.4th at p. 371.)

1. California's Anti-SLAPP Statute

In 1992 the Legislature enacted section 425.16 of the

Code of Civil Procedure.7 Under the statute, "[a]

defendant may bring a special motion to strike any cause

of action 'arising from any act of that person in

furtherance of the person's right of petition or free speech

under the United States Constitution or the California

Constitution in connection with a public issue.'"

(Bergstein v. Stroock & Stroock & Lavan LLP (2015) 236

Cal.App.4th 793, 803 [187 Cal. Rptr. 3d 36]

(Bergstein).)8 Courts are to construe the anti-SLAPP

statute broadly. (D.C. v. R.R. (2010) 182 Cal.App.4th

1190 [106 Cal. Rptr. 3d 399].)

7 Unless otherwise noted, all statutory references

are to the Code of Civil Procedure.

8 The statute includes within its definition of

acts in furtherance of protected free speech both

"written ... statement[s] ... made in a place open to

the public or a public forum in connection with an

issue of public interest" and "any ... conduct in

furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional

right of ... free speech in connection with a public

issue or an issue of public interest." (Code Civ.

Proc. 425.16, subd. (e)(3), (4)). ALADS did not

dispute in the trial court, nor does it here, that the

Times's publishing of news reports falls within

these statutory categories.

When ruling on an anti-SLAPP motion, the trial

court employs a two-step process. It first looks to see

whether the moving party has made a threshold showing

that the challenged causes of action arise from protected

activity. (Equilon Enterprises v. Consumer Cause, Inc.

(2002) 29 Cal.4th 53, 67 [124 Cal. Rptr. 2d 507, 52 P.3d

685] (Equilon).) If the moving party meets this threshold

requirement, the burden then shifts to the other party to

demonstrate a probability of prevailing on its claims.

(Ibid.) "In making these determinations, the trial court

considers 'the pleadings, and supporting and opposing

affidavits stating the facts upon which the liability or

defense is based.'" (Bergstein, supra, 236 Cal.App.4th at

p. 803, quoting 425.16, subd. (b)(2).)

2. The Trial Court Correctly Found ALADS's Complaint

Arises from the Times's Protected Activity: News

Reporting

ALADS asserts the trial court erred in finding the

Times had met its burden on the first step of the analysis

because the Times obtained the LASD files "through

criminal means." ALADS repeats the allegation from its

complaint that the Times reporter "stole, received from

someone else who stole, or otherwise unlawfully came

into physical possession of the confidential background

investigation files ... ." As the trial court correctly

observed, ALADS has presented no admissible evidence

that Faturechi or anyone else at the Times stole anything.

For this proposition in its brief, ALADS cites the

declaration of Sergeant Jay Moss. Sergeant Moss states

only that he has been "assigned to investigate the theft of

up to 500 background investigation files from the

Sheriff's Department." Moss also states that only

investigators, supervisors, and command staff are

"authorized to possess or review the contents" of the files.

ALADS cites Flatley v. Mauro (2006) 39 Cal.4th

299 [46 Cal. Rptr. 3d 606, 139 P.3d 2] (Flatley). There,

our Supreme Court held that "a defendant whose

assertedly protected speech or petitioning activity was

illegal as a matter of law, and therefore unprotected by

constitutional guarantees of free speech and petition,

cannot use the anti-SLAPP statute to strike the plaintiff's

complaint." (Id. at p. 305.) The court stated the rule this

way: where "either the defendant concedes, or the

evidence conclusively establishes, that the assertedly

protected speech or petition activity was illegal as a

matter of law, the defendant is precluded from using the

anti-SLAPP statute to strike the plaintiff's action." (Id. at

p. 320.) In Flatley a lawyer's letters and telephone calls to

the plaintiff "constituted criminal extortion as a matter of

law" and so were unprotected. (Id. at pp. 305, 332.) The

evidence of the defendant's communications was

uncontroverted. (Id. at p. 329.) The court emphasized its

conclusion that the defendant's communications

constituted criminal extortion as a matter of law was

"based on the specific and extreme circumstances of

[that] case."9 (39 Cal.4th at p. 332, fn. 16.)

9 (See Paul for Council v. Hanyecz (2001) 85

Cal.App.4th 1356, 1366-1367 [102 Cal. Rptr. 2d

864] (Paul), disapproved on another point in

Equilon, supra, 29 Cal.4th at p. 68, fn. 5

[defendant's conceded illegal money laundering,

Page 6

although arguably political conduct, was not

protected activity and not subject to special

motion to strike]; Novartis Vaccines &

Diagnostics, Inc. v. Stop Huntingdon Animal

Cruelty USA, Inc. (2006) 143 Cal.App.4th 1284,

1300 [50 Cal. Rptr. 3d 27] [individual activists'

terrifying

"home

visits"

of

plaintiffs'

employees--in which their windows were broken

and cars vandalized--were illegal activities as a

matter of law.].)

Cases decided after Flatley have held the Flatley rule

applies only to criminal conduct, not to conduct that is

illegal because it violates statutes (other than criminal

statutes) or the common law. (Bergstein, supra, 236

Cal.App.4th at p. 804; see Fremont Reorganizing Corp.

v. Faigin (2011) 198 Cal.App.4th 1153, 1169 [131 Cal.

Rptr. 3d 478]; Cross, supra, 197 Cal.App.4th at pp.

384-392 [rejecting plaintiff's claim that defendant's

disclosure of location of registered sex offender

constituted extortion and violated other Pen. Code

provisions as a matter of law; anti-SLAPP protection

available]; Mendoza v. ADP Screening & Selection

Services, Inc. (2010) 182 Cal.App.4th 1644, 1654 [107

Cal. Rptr. 3d 294] ["the Supreme Court's use of the

phrase 'illegal' was intended to mean criminal, and not

merely violative of a statute"].)

Bergstein, decided very recently by this court,

discusses the governing authorities on this point at some

length. There, the plaintiffs sued the lawyers who had

represented their adversaries in litigation over financial

transactions. The lawyer defendants filed an anti-SLAPP

motion. In opposition, the plaintiffs argued "their claims

did not arise from protected activity" because the

defendants had "participated in the theft of confidential

and privileged documents and information, and in the

unlawful purchase of claims" to force a bankruptcy in

violation of federal law. (Bergstein, supra, 236

Cal.App.4th at p. 802.) The plaintiffs submitted more

than 2,000 pages of documents, including e-mails among

the lawyers and others. The trial court granted the motion

and the Court of Appeal affirmed. The court discussed

Flatley, Mendoza, and many other cases, concluding the

illegality exception applies to statutory violations that

constitute criminal conduct and that, in any event, the

record did not establish the defendants' conduct was

illegal as a matter of law.

ALADS cites--and miscites--various statutes it

contends are violated by Faturechi's mere possession of

the records. For example, ALADS asserts that section

6200 of the Government Code makes it a crime for "any

person" to steal, remove, or secrete "official government

documents." But the statute does not say "any person." It

says "[e]very officer" who has custody of a record

"deposited in any public office" shall not steal, remove,

secrete, destroy, mutilate, deface, alter, or falsify the

record or permit another person to do so. (Ibid., italics

added.) Similarly, ALADS claims Government Code

section 3307.5 "makes it illegal, as a matter of law, for

anyone" to release a photograph of a peace officer to the

public. In fact, that statute concerns officers' relationships

with the agencies that employ them. It says officers shall

not be "required as a condition of employment" to

consent to the use of their photographs on the Internet.

(Ibid.)

ALADS also seems to assert that the Times's

possession of the files constitutes the crime of receiving

stolen property in violation of Penal Code section 496,

subdivision (a). First--as the trial court noted--ALADS

has presented no evidence10 that Faturechi or anyone else

at the Times "received" the files knowing they were

"stolen." (See CALCRIM No. 1750, setting forth the

elements of the crime.)11 Second--as the trial court

noted--ALADS has not distinguished, and cannot

distinguish, the "wealth of both State and Federal case

law, discussing the protection journalists and the press

enjoy under the First Amendment where there have been

allegations that published or disclosed content had been

illegally obtained."

10

ALADS asserts that the Times "had the

burden of proof on this issue." ALADS is

mistaken. "[O]nce the defendant has made the

required threshold showing that the challenged

action arises from assertedly protected activity,

the plaintiff may counter by demonstrating that

the [defendant's conduct] was illegal as a matter

of law because either the defendant concedes the

illegality of the assertedly protected activity or the

illegality is conclusively established by the

evidence presented in connection with the motion

to strike." (Soukup, supra, 39 Cal.4th at pp.

286-287; see Flatley, supra, 39 Cal.4th at pp.

313-315; Paul, supra, 85 Cal.App.4th at p. 1367

[if plaintiff contests validity of defendant's

exercise of protected rights and cannot

demonstrate as a matter of law that defendant's

CALIFORNIA JUDICIAL BRANCH NEWS SERVICE

CJBNS.ORG

Page 7

acts do not fall under anti-SLAPP statute, "then

the claimed illegitimacy of the defendant's acts is

an issue which the plaintiff must raise and support

in the context of the discharge of the plaintiff's

burden to provide a prima facie showing of the

merits of the plaintiff's case" (original italics)].)

11

As the court also noted, according to

ALADS's own allegations, the files belong to

LASD, not the individual deputies or their union.

A leading California case is Nicholson v. McClatchy

Newspapers (1986) 177 Cal.App.3d 509 [223 Cal. Rptr.

58]. Two newspapers reported that the State Bar's

commission had found the plaintiff unqualified for

appointment to the bench. The Government Code

required that commission ratings remain confidential.

The plaintiff sued the newspapers and the State Bar,

alleging violation of his right of privacy under the

California Constitution and the common law. The

plaintiff also alleged the defendants had conspired to

disclose the evaluation "to unauthorized persons and for

unauthorized purposes." (177 Cal.App.3d at p. 521.) The

trial court sustained the newspapers' demurrers and the

Court of Appeal affirmed. The court observed the

"plaintiff had the right to expect the State Bar's negative

evaluation would remain confidential and, undoubtedly,

someone acted in violation of this law in disclosing the

evaluation to the media defendants." (Id. at p. 516.) But,

the court said, "the First Amendment protects the ordinary

news-gathering techniques of reporters and those

techniques cannot be stripped of their constitutional

shield by calling them tortious." (Id. at p. 513.) The court

stated that ordinary news-gathering techniques "of

course, include asking persons questions, including those

with confidential or restricted information." (Id. at p.

519.) The court concluded, "While the government may

desire to keep some proceedings confidential and may

impose the duty upon participants to maintain

confidentiality, it may not impose criminal or civil

liability upon the press for obtaining and publishing

newsworthy information through routine reporting

techniques." (Id. at pp. 519-520.)12

12

ALADS cites Shulman v. Group W

Productions, Inc. (1998) 18 Cal.4th 200 [74 Cal.

Rptr. 2d 843, 955 P.2d 469] for the proposition

that the Times "has no constitutional protection

for unlawful news gathering [sic] activities." In

Shulman, a television cameraman recorded

footage, including audio, of an accident victim on

the highway and inside a medevac helicopter. A

production company later broadcast the footage as

part of a television reality show. The Supreme

Court held that the plaintiff victim could not sue

for public disclosure of private facts because the

subject of the broadcast was newsworthy. But, the

court said, triable issues of fact precluded

summary judgment for the production company

on the victim's intrusion claim for the recording

and broadcast of footage inside the helicopter.

The court held the cameraman's videotaping at the

accident scene on the highway was not actionable.

But the inside of the medevac helicopter was

essentially an ambulance, and the victim "was

entitled to a degree of privacy in her

conversations" with the nurse on board. (Id. at p.

233.) There is no allegation here that the Times

sent anyone into any of the deputies' hospital

rooms or eavesdropped on any conversation with

any medical provider. Nor did Shulman involve a

request for an injunction barring publication. The

footage in Shulman already had been broadcast.

Many other cases have reached the same result. (See,

e.g., Bartnicki v. Vopper (2001) 532 U.S. 514, 517, 535

[149 L. Ed. 2d 787, 121 S. Ct. 1753] [1st Amend.

protected journalists who reported contents of illegally

intercepted telephone conversations even though they

knew "or at least had reason to know" the interceptions

were unlawful; contentious collective bargaining

negotiations between school board and union were

matters of public concern]; Landmark Communications,

Inc. v. Virginia (1978) 435 U.S. 829 [56 L. Ed. 2d 1, 98

S. Ct. 1535] [1st Amend. protected newspaper from

criminal conviction for publishing confidential

proceedings of judicial review commission]. Cf. Cox

Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn (1975) 420 U.S. 469 [43 L.

Ed. 2d 328, 95 S. Ct. 1029] [1st Amend. protected

reporter who published rape victim's name in violation of

state criminal statute]; Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing

Co. (1979) 443 U.S. 97 [61 L. Ed. 2d 399, 99 S. Ct. 2667]

[invalidating state law that criminalized publication of

juvenile murder suspect's name without court

permission]; The Florida Star v. B. J. F. (1989) 491 U.S.

524 [105 L. Ed. 2d 443, 109 S. Ct. 2603] [1st Amend.

protected newspaper that published rape victim's

name--inadvertently released by police--in violation of

state criminal statute].)

For all of these reasons, the trial court correctly

Page 8

found the "illegal conduct" exception to the anti-SLAPP

statute inapplicable in this case.

3. The Trial Court Correctly Found the Injunction

ALADS Sought Would Be an Unconstitutional Prior

Restraint

ALADS contends that--even if its complaint arises

from protected activity and the Times was entitled to

bring an anti-SLAPP motion--the complaint adequately

alleged a cause of action for invasion of privacy and the

injunction for which it prayed was not a prior restraint.

As noted above, ALADS's complaint alleged a single

cause of action for injunctive relief. That cause of action

alleges that the Times intends to "release to the public

confidential information from peace officer personnel

files, including but not limited to private, confidential and

legally privileged and protected personnel, education,

credit and medical information"; that the Times is

"precluded by law" from "releasing any confidential

information" from the files; that the individual plaintiffs

"have no adequate, speedy remedy at law"; and that they

will suffer irreparable harm if the court does not enjoin

the Times's "illegal publication" of their "confidential

information."

ALADS

argues

that

these

allegations--taken together with all of the factual

allegations of its complaint--"assert harm suffered by the

invasion of their right of privacy."

ALADS seems not to claim that it has stated a cause

of action for any of the four common law privacy torts.13

Instead, ALADS appears to contend that its complaint

stated "a cause of action for invasion of privacy in

violation of article I, section 1 of the California

Constitution." "An actionable claim requires three

essential elements: (1) the claimant must possess a legally

protected privacy interest [citation]; (2) the claimant's

expectation of privacy must be objectively reasonable

[citation]; and (3) the invasion of privacy complained of

must be serious in both its nature and scope [citation]. If

the claimant establishes all three required elements, the

strength of that privacy interest is balanced against

countervailing interests. [Citation.]" (County of Los

Angeles v. Los Angeles County Employee Relations Com.

(2013) 56 Cal.4th 905, 926 [157 Cal. Rptr. 3d 481, 301

P.3d 1102], citing Hill v. National Collegiate Athletic

Assn. (1994) 7 Cal.4th 1, 35-38 [26 Cal. Rptr. 2d 834,

865 P.2d 633].)

13 These are public disclosure of private facts,

false light, intrusion into private affairs, and

appropriation of name and likeness. (5 Witkin,

Summary of Cal. Law (10th ed. 2005) Torts,

651 at pp. 957-958.)

The first problem with ALADS's argument is that

any privacy right in the information contained in

deputies' employment applications belongs to the

deputies (and their employer, LASD), not to the deputies'

labor union. "It is well settled that the right of privacy is

purely a personal one; it cannot be asserted by anyone

other than the person whose privacy has been invaded,

that is, plaintiff must plead and prove that his privacy has

been invaded." (Hendrickson v. California Newspapers,

Inc. (1975) 48 Cal.App.3d 59, 62 [121 Cal. Rptr. 429]

(original italics) [family members could not bring privacy

suit against newspaper that published obituary revealing

decedent's criminal conviction]; cf. Roberts v. Gulf Oil

Corp. (1983) 147 Cal.App.3d 770, 791 [195 Cal. Rptr.

393] [California's "constitutional [privacy] provision

simply does not apply to corporations. The provision

protects the privacy rights of people." (orignal italics)].)

As the only cause of action even arguably pleaded in the

complaint is invasion of privacy under the California

Constitution, ALADS has no standing to prosecute this

case.

In any event, we need not determine whether the

complaint as pleaded adequately alleges a cause of action

by the individual unnamed Doe plaintiffs for invasion of

privacy under the California Constitution because the

injunction plaintiffs seek would be an unconstitutional

prior restraint. The seminal case, of course, is the

Pentagon Papers case, New York Times Co. v. United

States (1971) 403 U.S. 713 [29 L. Ed. 2d 822, 91 S. Ct.

2140]. There, the United States sought to enjoin The New

York Times and the Washington Post from publishing the

contents of a classified study about the Vietnam conflict.

(Id. at p. 714.) As Chief Justice Burger observed in a later

case, in New York Times "[e]ach of the six concurring

Justices and the three dissenting Justices expressed his

views separately, but 'every member of the Court, tacitly

or explicitly, accepted the Near [v. Minnesota (1931) 283

U.S. 697 [75 L. Ed. 1357, 51 S. Ct. 625]] and

[Organization for a Better Austin v.] Keefe [(1971) 402

U.S. 415 [29 L. Ed. 2d 1, 91 S. Ct. 1575]] condemnation

of prior restraint as presumptively unconstitutional.'

[Citation.]" (Nebraska Press, supra, 427 U.S. at pp.

558-559.) Justice White noted that the United States

Criminal Code contained "numerous provisions" that the

Page 9

newspapers might violate if they published--for

example--classified information about communication

intelligence activities. (Id. at p. 735 (conc. opn. of White,

J.).) Justice White cited a provision of the Criminal Code

that made it "a criminal act for any unauthorized

possessor of a document 'relating to the national defense'"

to "communicate" it to any unauthorized person or to

retain it. (New York Times, supra, 403 U.S. at p. 737

(conc. opn. of White, J.).) Justice White stated, "[T]he

newspapers are presumably now on full notice of the

position of the United States and must face the

consequences if they publish." (Id. at pp. 736-737 (conc.

opn. of White, J.).) Nevertheless, Justice White joined in

the court's decision "because of the concededly

extraordinary protection against prior restraints enjoyed

by the press under our constitutional system." (Id. at pp.

730-731 (conc. opn. of White, J.).) Other justices spoke

more forcefully. Justice Black quoted Founding Father

James Madison: "'The people shall not be deprived or

abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish

their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of

the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.'" (Id. at

p. 716 (conc. opn. of Black J.).) Justice Brennan added,

"So far as I can determine, never before has the United

States sought to enjoin a newspaper from publishing

information in its possession." (Id. at p. 725 (conc. opn.

of Brennan, J.).)

The cases invalidating prior restraints--especially

restraints on publication by the press--are legion. (See,

e.g., ; Vance v. Universal Amusement Co., Inc. (1980)

445 U.S. 308 [L. Ed. 2d 413, 100 S. Ct. 1156, 63] [public

nuisance statute that authorized state judge to enjoin

exhibition of obscene films was unconstitutional prior

restraint]; Nebraska Press, supra, 427 U.S. 539

[invalidating restriction on reporting about criminal

defendant's confession even though report might

jeopardize defendant's 6th Amend. rights]; Near v.

Minnesota, supra, 283 U.S. at pp. 718-719 & fn. 11

["The fact that for approximately one hundred and fifty

years there has been almost an entire absence of attempts

to impose previous restraints upon publications relating

to the malfeasance of public officers is significant of the

deep-seated conviction that such restraints would violate

constitutional right."]; Organization for a Better Austin v.

Keefe, supra, 402 U.S. at p. 418 [invalidating court order

that enjoined community organization from distributing

leaflets that plaintiff claimed violated his privacy; "[i]t is

elementary, of course, that in a case of this kind the

courts do not concern themselves with the truth or

validity of the publication"]; In re Providence Journal

Co. (1986) 820 F.2d 1342 (Providence Journal) [court

order that newspaper not publish report based on illegal

FBI surveillance, in violation of privacy rights, was

invalid prior restraint].) The California Constitution

"'provides an even broader guarantee of the right of free

speech and the press than does the First Amendment.

[Citation.]'" (Freedom Communications, Inc. v. Superior

Court (2008) 167 Cal.App.4th 150, 154 [83 Cal. Rptr. 3d

861].)

ALADS contends the injunction it seeks to prevent

the Times from publishing is "content neutral" and

therefore not a prior restraint. ALADS also argues an

injunction restraining speech "may issue in some

circumstances to protect private rights."14 None of the

cases ALADS cites involved an injunction barring the

press from reporting or publishing news articles. (See

Madsen v. Women's Health Center, Inc. (1994) 512 U.S.

753 [129 L. Ed. 2d 593, 114 S. Ct. 2516] [upholding

court order that enjoined protesters from entering buffer

zone around abortion clinic and from assaulting patients,

but striking down as unconstitutional portion of

injunction that prohibited protesters from displaying

images to patients]; Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Human Rel.

Comm'n (1973) 413 U.S. 376, 388, 391 [37 L. Ed. 2d

669, 93 S. Ct. 2553] [city ordinance forbidding

newspapers from listing help-wanted ads by gender was

not unconstitutional; discrimination in employment is

illegal commercial activity; court's decision does not

"authorize any restriction whatever ... on stories or

commentary originated by Pittsburgh Press"; court

"reaffirm[s] unequivocally the protection afforded to

editorial judgment and to the free expression of views on

these and other issues, however controversial"]; DVD

Copy Control Assn., Inc. v. Bunner (2003) 31 Cal.4th

864, 871 [4 Cal. Rptr. 3d 69, 75 P.3d 1] [upholding

injunction that issued to prevent defendant's ongoing

misappropriation of digital "master keys" and algorithms

that were plaintiff's trade secrets]; Aguilar v. Avis Rent A

Car System, Inc. (1999) 21 Cal.4th 121, 138 [87 Cal.

Rptr. 2d 132, 980 P.2d 846] [upholding injunction that

barred Latino employees' manager from verbally and

physically harassing them--for example, from calling

them "motherfuckers"--because jury already had found

that manager's conduct constituted employment

discrimination; injunction "simply precluded defendants

from continuing their unlawful activity"]; Planned

Parenthood Shasta-Diablo, Inc. v. Williams (1995) 10

Cal.4th 1009 [43 Cal. Rptr. 2d 88, 898 P.2d 402]

CALIFORNIA JUDICIAL BRANCH NEWS SERVICE

CJBNS.ORG

Page 10

[affirming injunction after trial that kept abortion

protesters from blocking entrance to clinic; "place

restriction" that required demonstrating to take place

across the street on public sidewalk was content-neutral].)

14 ALADS takes this phrase from Wilson v.

Superior Court (1975) 13 Cal.3d 652, 662 [119

Cal. Rptr. 468, 532 P.2d 116]. In Wilson the

California Supreme Court unanimously held

unconstitutional, as a prior restraint, a court order

that enjoined a candidate from distributing a

libelous newsletter about his opponent. Justice

Mosk, writing for the court, discussed all of the

United States Supreme Court cases including the

then recent Pentagon Papers case. Following the

phrase on which ALADS relies, the court cited

Magill Bros. v. Bldg. Service etc. Union (1942) 20

Cal.2d 506, 511-512 [127 P.2d 542]. In Magill

the court held a bowling alley was entitled after

trial to an injunction barring a union that sought to

represent its employees from picketing in front of

the bowling alley.

Moreover, the injunction ALADS seeks would not

be "content-neutral" at all. ALADS asks the court to

enjoin the Times from publishing any article containing

any information in 16 listed categories, including the

names of any OPS/LASD deputies, their photographs,

and their "non-public criminal history."

In sum, ALADS has cited no case permitting the

kind of injunction it seeks here, to restrain a newspaper

from publishing news articles on a matter of public

concern: the qualifications of applicants for jobs as law

enforcement officers. ALADS has cited no case because

there is no such case. For more than 100 years, federal

and state courts have refused to allow the subjects of

potential news reports to stop journalists from publishing

reports about them. (Providence Journal, supra, 820 F.2d

at pp. 1348-1349 ["In its nearly two centuries of

existence, the Supreme Court has never upheld a prior

restraint on pure speech."; the Supreme Court has never

upheld a prior restraint on the publication of news].) If

and when the Times publishes any article that constitutes

actionable libel or invasion of privacy about any

individual deputy, that deputy remains free to file any

lawsuit he or she can plead and prove in good faith. (Id.

at pp. 1345, 1349 [that publication would infringe

privacy rights is insufficient basis for issuing prior

restraint; remedy is subsequent action for damages].)

4. ALADS Has Not Shown the Trial Court Abused Its

Discretion in Ruling on the Times's Objections to

ALADS's Declarations

Finally, ALADS contends the trial court "erred in its

evidentiary rulings." We find no abuse of discretion.

Under the abuse of discretion standard of review,

appellate courts will disturb discretionary trial court

rulings only upon a showing of "a clear case of abuse"

and "a miscarriage of justice." (See Blank v. Kirwan

(1985) 39 Cal.3d 311, 331 [216 Cal. Rptr. 718, 703 P.2d

58]; Denham v. Superior Court (1970) 2 Cal.3d 557, 566

[86 Cal. Rptr. 65, 468 P.2d 193].) A trial court abuses its

discretion only when it "'exceeds the bounds of reason,

all of the circumstances before it being considered.'"

(Denham, at p. 566; see Sargon Enterprises, Inc. v.

University of Southern California (2012) 55 Cal.4th 747,

773 [149 Cal. Rptr. 3d 614, 288 P.3d 1237].)

Substantial portions of the ALADS declarations were

admitted into evidence on the anti-SLAPP motion, either

because the Times did not object to them or because the

trial court overruled the Times's objections. This admitted

evidence includes:

--Descriptions by a lieutenant and a sergeant in the

LASD personnel bureau of what information applicants

are required to provide, how extensive that information

is, how background checks are conducted, what kinds of

questions references are asked, the fact that LASD tells

applicants as well as references that LASD will keep

what they say in confidence, and the fact that the

personnel bureau has not authorized anyone to give the

files to anyone outside the bureau. (Declaration of Milton

Murphy, pars. 1-7, 10; declaration of Cynthia McDaniel,

pars. 1-3, 4, 2d sentence, 5, 6, 7, 1st and 3d sentences,

12.)

--Statements by two Doe plaintiffs that they provided

extensive personal information to LASD on their

application forms. One of the two said when he applied

he "underst[ood]" LASD would maintain his

"information" as "confidential." (Declaration of Deputy

John Doe-3, pars. 1-5; declaration of John Doe-14, pars.

1, 3-6.)

--Statements by a police officer--who also owns a

company that "assist[s] ... law enforcement personnel in

protecting their private information on the internet"--that

gang members and "[c]areer criminals" take pride in

Page 11

shooting and killing police officers. (Declaration of

Kevin Shaw, pars. 1-7.)

The trial court also sustained a number of the

Times's objections to ALADS's declarations. Some of the

statements not admitted into evidence include:

The trial court sustained some objections to the

ALADS's witnesses' statements about what Faturechi had

said to them and what they had said to him, and overruled

others. (Compare declaration of Doe-3, pars. 11, 13, 14,

14 [sic]; declaration of Doe-14, pars. 9-10 with

declaration of Doe-3, pars. 7-9; declaration of Doe-14,

pars. 11, 14.) While both Doe-3 and Doe-14 could testify

as to what they put in their applications for LASD jobs,

they could not testify as to what documents and

information Faturechi had or did not have, as the trial

court correctly ruled.

--Legal conclusions. (See, e.g., Declaration of

Cynthia McDaniel, par. 7, 2d sentence; declaration of Jay

Moss, pars. 10, 11.)

We have reviewed each of the 54 objections the trial

court sustained as well as each of the 15 it overruled. We

have found no abuse of discretion.

--Hearsay and statements lacking foundation. (See,

e.g., Declaration of Doe-3, par. 15; declaration of Kevin

Shaw, pars. 9-15; declaration of Elizabeth J. Gibbons,

pars. 7, 9-15.)

DISPOSITION

--Statements by an LASD sergeant that he is

investigating "the theft of up to 500 background

investigation files" from LASD. (Declaration of Jay

Moss, pars. 1-8.)

--Statements purporting to testify to Faturechi's

intent. (Declaration of Doe-3, par. 14.)

--Improper lay opinion15 or conclusions. (See, e.g.,

Declaration of Milton Murphy, pars. 8, 9; declaration of

Cynthia McDaniel, par. 11, 4th sentence; declaration of

Doe-3, pars. 17, 19; declaration of Doe-14, par. 20.)

15

ALADS asserts that Lieutenant Murphy,

Sergeant McDaniel, and the man identified only

as "Deputy John Doe-3" are experts. ALADS did

not make this argument in the trial court.

Therefore, it has waived it. (Greenwich S.F., LLC

v. Wong (2010) 190 Cal.App.4th 739, 767 [118

Cal. Rptr. 3d 531]; Ochoa v. Pacific Gas &

Electric Co. (1998) 61 Cal.App.4th 1480, 1488,

fn. 3 [72 Cal. Rptr. 2d 232].)

--Some of Shaw's statements about crimes

committed in other jurisdictions against peace officers.

(Cf. Long Beach Police Officers Assn. v. City of Long

Beach (2014) 59 Cal.4th 59, 65, 75 [172 Cal. Rptr. 3d

56, 325 P.3d 460] (LBPOA) [declaration by police

department lieutenant that revelation of officers' names

could expose officers and their families to harassment

and gang retaliation expressed "concerns" only "general

in nature"].)

Law enforcement officers protect the public. They

prevent crime, and they investigate and make arrests

when crimes occur. They carry and use firearms and

other weapons. They are authorized to use deadly force

and to restrain individual liberty. The public has a strong

interest in the qualifications and conduct of law

enforcement officers. "... 'Peace officers "hold one of the

most powerful positions in our society; our dependence

on them is high and the potential for abuse of power is

far from insignificant."'" (LBPOA, supra, 59 Cal.4th at p.

73, quoting City of Hemet v. Superior Court (1995) 37

Cal.App.4th 1411, 1428 [44 Cal. Rptr. 2d 532].) Here, a

labor union and unnamed officers seek to stop a

newspaper from publishing news reports about the hiring

and evaluation of officers, including allegations of past

misconduct. "Of all the constitutional imperatives

protecting a free press under the First Amendment, the

most significant is the restriction against prior restraint

upon publication." (Providence Journal, supra, 820 F.2d

at p. 1345.) The trial court properly granted the Times's

anti-SLAPP motion. We affirm the order. Respondents

are entitled to recover their costs on appeal.

Kitching, Acting P. J., and Aldrich, J., concurred.

Appellants' petition for review by the Supreme Court

was denied November 18, 2015, S228983.

CALIFORNIA JUDICIAL BRANCH NEWS SERVICE

CJBNS.ORG

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Motion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Документ15 страницMotion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (2)

- Placing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportДокумент153 страницыPlacing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas50% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Appellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaДокумент50 страницAppellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Sample Requests For Admission Under Rule 36Документ2 страницыSample Requests For Admission Under Rule 36Stan Burman57% (7)

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaДокумент9 страницIn The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkДокумент44 страницыAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Federal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteДокумент55 страницFederal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictДокумент13 страницIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeДокумент11 страницAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Prosecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyДокумент2 страницыProsecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Respondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryДокумент135 страницRespondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Breach of DutyДокумент4 страницыBreach of DutyLady Bernadette PayumoОценок пока нет

- Counter-Affidavit Ruth Gurrea TaalДокумент4 страницыCounter-Affidavit Ruth Gurrea TaalDence Cris RondonОценок пока нет

- Opposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Документ6 страницOpposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Dr.-Borgy-Dela-Cruz JAДокумент6 страницDr.-Borgy-Dela-Cruz JABorgy Dela CruzОценок пока нет

- People v. Rodil conviction upheldДокумент2 страницыPeople v. Rodil conviction upheldShirley BonillaОценок пока нет

- Valenzuela Vs PeopleДокумент1 страницаValenzuela Vs Peopleice.queenОценок пока нет

- 2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtДокумент24 страницы2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- DA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyДокумент4 страницыDA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Terry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketДокумент64 страницыTerry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Prosecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeДокумент1 страницаProsecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- E.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCAДокумент55 страницE.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCACalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Silicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsДокумент8 страницSilicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- District Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeДокумент1 страницаDistrict Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- "GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsДокумент4 страницы"GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Judge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201Документ38 страницJudge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Opposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Документ4 страницыOpposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Garrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloДокумент2 страницыGarrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

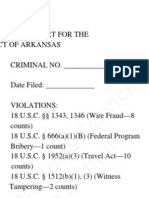

- Federal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasДокумент13 страницFederal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Judicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaДокумент3 страницыJudicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantДокумент4 страницыIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Judge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliДокумент10 страницJudge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Profile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictДокумент3 страницыProfile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefДокумент19 страницIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Qeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictДокумент2 страницыQeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- 3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMДокумент9 страниц3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasОценок пока нет

- Corpuz v. People PhilippinesДокумент2 страницыCorpuz v. People PhilippinesSamuel WalshОценок пока нет

- 1.4 G.R. No. 5887, U.S. v. Look Chaw, 18 Phil. 573Документ3 страницы1.4 G.R. No. 5887, U.S. v. Look Chaw, 18 Phil. 573Juris FormaranОценок пока нет

- Notice To The Court Exhibit AДокумент3 страницыNotice To The Court Exhibit ATom LambОценок пока нет

- People Vs PalmonesДокумент8 страницPeople Vs PalmonesDan LocsinОценок пока нет

- People vs Mariano: Affidavit details buy-bust operation arresting two for illegal drug saleДокумент7 страницPeople vs Mariano: Affidavit details buy-bust operation arresting two for illegal drug saleGuevarra RemОценок пока нет

- Affadavit of Service by Chris Gaubatz in CAIR Racketeering CaseДокумент6 страницAffadavit of Service by Chris Gaubatz in CAIR Racketeering CasejpeppardОценок пока нет

- Spec ProДокумент9 страницSpec ProAndrei ArkovОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law FDДокумент24 страницыCriminal Law FDSushrut ShekharОценок пока нет

- Directors Cannot Be Prosecuted Without Arraigning The Company As AccusedДокумент7 страницDirectors Cannot Be Prosecuted Without Arraigning The Company As AccusedLive Law100% (1)

- Tutoral Law Chapter 1 & 2 (Sem 1) (2018)Документ6 страницTutoral Law Chapter 1 & 2 (Sem 1) (2018)waniОценок пока нет