Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Violenta Domestica/protectia Copilului

Загружено:

Stoica Ioana CristinaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Violenta Domestica/protectia Copilului

Загружено:

Stoica Ioana CristinaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Child Abuse

Domestic

Review Violence

Vol. 16: 311322

in New South

(2007)Wales, Australia

Published online in Wiley InterScience

(www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/car.991

Domestic Violence:

A Priority in Child

Protection in New

South Wales,

Australia?

311

Jude Irwin*

Fran Waugh

Faculty of Education and Social

Work, University of Sydney,

Australia

Over the last several years there has been increasing awareness of

the connection between domestic violence and child abuse, yet only

minimal attention has been paid to the implications of this for child

protection practice. This article begins to address this gap. Drawing on

research undertaken in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, it examines

child protection practice in relation to children and young people who

have been exposed to domestic violence. The research involved

analysis of the responses of the statutory child protection authority

in NSW (the Department of Community Services or DoCS) to abuse

allegations involving domestic violence. The data are drawn from

observation and analysis of the initial responses to referrals to DoCS

and the tracking of a sample of these referrals over an 18 month

period. From the data obtained, it is evident that domestic violence

referrals are treated less seriously than other referrals, with more

being confirmed as abuse but fewer resulting in follow up or

intervention. The implications of this for child protection practice are

teased out. Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Increasing

awareness of

the connection

between domestic

violence and child

abuse

Domestic violence

referrals are treated

less seriously than

other referrals

KEY WORDS: domestic violence; child abuse; child protection

ver the last 15 years in the western world, including Australia,

there has been increasing attention paid to the effects of

domestic violence on children. Research undertaken in Britain,

the USA, Canada and Australia shows that there is frequently a

link between domestic violence and child abuse, with the presence

of one form of violence often being associated with the other

(James, 1994; Jaffe et al., 1990; OKeefe, 1995; Laing, 2000;

Edleson, 2001; Jourles et al., 2001; Mullender et al., 2002; Calder

Correspondence to: Associate Professor Jude Irwin, Faculty of Education and Social

Work, Building A35, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. E-mail: J.Irwin@edfac.

usyd.edu.au

Contract/grant sponsor: Australian Research Council; Barnardos, Australia; NSW Department

of Community Services.

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

312

How do

practitioners make

sense of this in

their practice?

Irwin and Waugh

et al., 2004; Humphreys and Stanley, 2006; Radford and Hester,

2006). How has child protection practice been influenced by

this knowledge? How do practitioners make sense of this in their

practice? This article addresses these questions utilising research

undertaken in NSW, Australia which explored statutory child

protection practitioners responses to domestic violence. To

contextualise the research, the article begins with a brief overview

of the social and political background in both federal and state

arenas (particularly NSW) and provides an outline of early policy

responses to child protection in relation to domestic violence.

Australia: The Social, Political and Legal Context

All except Western

Australia have some

form of mandatory

reporting of child

abuse

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

In just over a decade of conservative federal government in

Australia, there has been an erosion of services to women living

with domestic violence. A concerted move towards the consolidation of the family has resulted in a dismantling of many of the

policies and services that had been put into place by previous

governments. These have included: a decrease in child care subsidies so increasing costs to users; dismantling of youth training

schemes; tighter controls over youth allowances resulting in families having to financially support young people for longer time

periods; cutbacks to legal aid which have had a negative impact

on womens access to justice; reductions in supported accommodation schemes, affecting funding to refuges (shelters) and

emergency accommodation and support services; and privatisation

of family court support services and the movement to negotiated

settlements.

In Australia, statutory child protection work is the responsibility

of the state and territory governments. There are differences in

legislation and procedures between the states but all except Western Australia have some form of mandatory reporting of child abuse.

This research was undertaken in NSW, the most populous state in

Australia, over a four year period: 1997 to 2001. In 2000, towards

the end of the data collection for this project, new child protection

legislation was .introduced. The NSW Children and Young Persons

(Care and Protection) Act 1998 (NSW Government, 1998) was

proclaimed in 2000. Section 23(d) of the Act states that a child

or young person is at risk of harm if current concerns exist for

the safety, welfare or well-being of the child or young person

because of the presence of domestic violence. We argue that,

despite this inclusion, domestic violence remains a key issue in

child protection (see for example NSW Child Death Review

Team, 2002; NSW Ombudsman, 2004, 2005, 2006) and the issues

identified in this research remain relevant for practitioners and

policy makers.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

Domestic Violence in New South Wales, Australia

313

NSW: Early Policy and Practice Responses to Children

Protection and Domestic Violence

It was six years earlier, in June 1994, that domestic violence

was introduced into child protection procedures as a new child at

risk notification category: emotional abuse due to exposure to

domestic violence. This was the first time that exposure to domestic violence could be recorded as a form of child abuse. The change

evoked both positive and negative responses from professionals

working in the areas of child protection and domestic violence

(Irwin and Wilkinson, 1997). In February 1997, there were further

changes as exposure to domestic violence was replaced by three

separate categories relating to:

The first time

that exposure to

domestic violence

could be recorded

as a form of child

abuse

1. the behaviour of the carer;

2. risk or harm to a child as a result of intervening in domestic

violence; and

3. risk to a child as a consequence of witnessing violence.

Prior to and at the time this research was undertaken, workplace

factors played an influential part in the day to day practice of statutory child protection workers. In the decade prior to the research,

there were major restructures of the statutory child protection

authority resulting in closure of offices; downsizing of management

numbers; an overall reduction of staff numbers; and the demoralisation of child protection workers with high turnover of staff

(Perrin, 1992; Humphreys, 1993; Waugh, 1997). When the research

was undertaken, the workplace factors at local offices continued

to be unstable and included: ongoing staff shortages; high staff

turnover; a large variation in child protection practice knowledge

and experience held by intake workers; differing team structures

from office to office; differing decision-making processes between

offices; high workloads necessitating the prioritising of crisis

responses; the number of referrals outweighing the capacity to

respond which resulted in cases remaining unallocated; and varying levels of supervision of intake workers (Irwin et al., 2002). It

was in this turbulent context of rapid policy change, diminishing

resources and challenging work practices that the research project

described in this article commenced.

When the research

was undertaken, the

workplace factors

at local offices

continued to be

unstable

The Research

The aims of the overall research project were to:

1. examine practitioners knowledge and understandings of domestic

violence;

2. review the child protection strategies utilised by practitioners; and

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

314

Irwin and Waugh

3. identify effective strategies which could be used in responding to

both women and their children.

An intended

outcome of the

research was the

development of a

template of good

practice

An intended outcome of the research was the development of a

template of good practice for practitioners which would address

the rights, needs and interests of women and their children who had

lived with domestic violence.

The project included four related studies undertaken over a four

year period:

1. The observation and analysis of responses to domestic violence

at five statutory child protection offices in NSW over a 20 day

period, followed by the tracking of a sample of these referrals

over 18 months. The views of intake workers and their supervisors

were also sought.

2. The exploration of practitioners understandings of the child protection practice and policy issues related to children and young

people who live with domestic violence.

3. The exploration of womens experiences of living with domestic

violence and the protection of their children.

4. The exploration of how children and young people managed

living with domestic violence.

It is the first of these studies: the analysis of the statutory responses

to domestic violence, which is the focus of this article.

Outline of Statutory Child Protection Intake Process in

NSW in 19972000

When a referral

was first received

there were three

possible decisions

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

The statutory child protection offices participating in the research

all employed designated intake staff who responded to the incoming referrals. The responses involved collecting relevant information, undertaking a preliminary assessment to clarify issues and

preparing a plan of action which was presented to their supervisor.

During the period when the research was undertaken, there were

various decision-making points in statutory child protection practice which would result in referrals either being filtered out, thus

not requiring further investigation, or remaining in the system to

be further investigated. When a referral was first received there were

three possible decisions that could be made:

1. The referral could be recorded as information onlythis was if

the allegation was not considered serious. No further action would

be taken.

2. The referral could be recorded as intake only on the Client

Information System (CIS)this was when the allegation was

considered more serious. These referrals involved minimal or no

follow up.

3. An allegation considered the most serious would be recorded as

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

Domestic Violence in New South Wales, Australia

315

a notification on the CIS. At the time of the research this was the

official recording of the child abuse allegation and involved follow up. (The nomenclature for notification changed to report in

new child protection legislation in 2000.)

If a decision was made to record the allegation as a notification, the

next step was to decide whether an investigative assessment would

be undertaken. This involved consultation with senior staff, other

relevant agencies and the family to complete a more detailed

risk assessment. The five possible outcomes of an investigative

assessment were:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

confirmed, registered;

confirmed, referred, closed;

confirmed, closed;

not confirmed, referred, closed; or

not confirmed, closed and not located.

Five possible

outcomes of an

investigative

assessment were

Collecting the Data

This part of the research study explored how the Department

of Community Services (DoCS) in NSW (the child protection

statutory authority) responded to reports of child abuse, particularly

those which involved domestic violence. It involved three aspects.

Observation and Analysis of Intake Practices at Five Offices of

the NSW DoCS

Researchers at each of the five participating offices shadowed

an intake worker and used a structured questionnaire to collect

information on each referral over the observation period. Data

were collected on all child abuse referrals not only those involving

domestic violence. Two of the offices were located in the urban

areas of Sydney and three were in rural NSW.

The Tracking of a Sample of Intake Referrals Over an

18 Month Period

Researchers at

each of the five

participating

offices shadowed

an intake worker

and used a

structured

questionnaire

A sample of the referrals was tracked over 18 months. This included

all referrals where domestic violence was the primary reason

for referral and a similar number of other referrals. A structured

questionnaire was used to collect information from the files and CIS

on: family composition and social supports; nature, frequency, time

frame and outcome of intervention by the DoCS; and the involvement of other agencies and any inter-agency work with the family.

The purpose of this was to provide information about the outcome

on any intervention.

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

316

Irwin and Waugh

Interviews with Intake Workers and Assistant Managers Who

Participated in the Project

An interview guide was used to elicit information from intake

workers and any staff who had decision-making responsibilities

concerning the referrals. Information was sought about professional

background and experience, understandings of domestic violence

and the role of statutory child protection personnel in responding

to situations when domestic violence was present. Practitioners

views were also sought on the availability of professional supervision, workloads, the adequacy of staffing levels and resources,

workplace practices and the work environment.

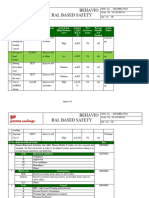

The Intake Data

A total of 431

referrals were

observed in the

five participating

offices

During the observation period a total of 431 referrals were observed

in the five participating offices (see Figure 1). Domestic violence

was the highest primary grounds for referral, with 111 (26%). The

next highest referral was physical harm (72 referrals <17%).

Just over 50% (217) of the 431 initial referrals were tracked over a

period of 18 months after the observation period.

Comparison of Domestic Violence and Other Referrals

A higher

percentage of

domestic violence

referrals were

recoded as

information only

A similar percentage of referrals for domestic violence as for other

forms of child abuse and neglect initial referrals were recorded

as notifications (56% (62) of domestic violence referrals and 58%

(188) of other referrals). However, a higher percentage of domestic violence referrals were recoded as information only, namely

13% (14) domestic violence referrals and seven per cent (21) other

referrals. Thus, at this early stage in the child protection process,

domestic violence appeared to be assessed as less serious than other

forms of abuse and is therefore less likely to be recorded on the

CIS to the same extent as other referrals. This effectively discounts

Figure 1. All observed referrals

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

Domestic Violence in New South Wales, Australia

domestic violence in child protection practice with the consequences of no follow up, ongoing involvement with the family or

referral to another service.

A similar picture emerged in relation to notifications. Even though

a similar percentage of the initial domestic violence and other

referrals were recorded as notifications, there was a significant

difference between the percentage of domestic violence referrals

and all other tracked referrals which were followed up with investigative assessments. Investigative assessments were pursued in

36% (40) of the domestic violence notifications and 52% (55) of the

other notifications. Again it is evident that referrals on the primary

grounds of domestic violence were less likely to be followed up with

an investigative assessment than referrals on other grounds.

There was also great disparity between confirmation of the

domestic violence and other abuse referrals, namely, 75% of

the initial domestic violence referrals were confirmed and 56%

of the other initial referrals were confirmed. Although a higher

percentage of domestic violence referrals were confirmed, only 16%

(three) of the confirmed domestic violence referrals were recorded

as registered cases, whereas 63% (19) of the other confirmed

referrals were recorded as registered cases. So, although more likely

to be confirmed, referrals based on domestic violence were less

likely to be registered and result in an ongoing response from statutory child protection workers.

317

Only 16% of the

confirmed domestic

violence referrals

were recorded as

registered cases

Re-referrals

Over the 18 month tracking period, 88 of the original referrals were

re-reported to statutory child protection authorities on one or more

occasion. Of these 69% resulted in a notification, with similar

rates for both the domestic violence and other categories of abuse.

As with the initial referrals, a higher percentage of domestic

violence re-referrals resulted in an intake only decision and were

filtered out of the child protection system. The domestic violence

re-referrals were again less likely to result in investigative assessments and registration. Investigative assessments were undertaken

in 55% of domestic violence referrals and 68% of other referrals.

Only 19% of domestic violence re-referrals were registered compared with 48% of the other re-referrals.

From these data, a clear pattern emerged that domestic violence

was treated differently from other abuse referrals. Despite being the

highest reason for original referrals, the data show that domestic

violence is either not considered as a child protection issue or is

responded to less seriously than other forms of abuse and neglect.

At all stages of statutory child protection intervention, domestic

violence referrals were filtered out at a far greater rate than

other referrals. At intake, a greater number of domestic violence

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Domestic violence

referrals were

filtered out at a far

greater rate than

other referrals

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

318

Domestic violence

re-referrals being

much less likely to

be registered

Irwin and Waugh

referrals were recorded as information only, a lower proportion

underwent investigative assessments and a higher percentage

were confirmed but fewer were registered and followed up. A

similar pattern emerged with re-referrals with domestic violence

re-referrals being much less likely to be registered than other

referrals and more likely to be referred to other support services

and closed. The interviews undertaken with the intake workers

and their supervisors provide a partial explanation for this.

Interviews with Statutory Child Protection Workers

These two groups

struggled to identify

domestic violence

unless it was very

obvious

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Although the child at risk category emotional abuse due to exposure to domestic violence had been included as a reason for child

abuse referrals in June 1994, less than half of the 20 practitioners

interviewed had undertaken training about assessing risk related

to domestic violence. The domestic violence knowledge of the

statutory child protection practitioners in this study varied considerably and fell into four broad groups. The first group of practitioners perceived that domestic violence was not a child protection

issue unless the child was physically hurt or saw the abuse of their

mother. These practitioners tended to have narrow understandings

of domestic violence as either physical abuse, or the threat of such

abuse. They had limited knowledge of the dynamics of domestic

violence, especially as it related to children. While the second group

of practitioners had a greater knowledge and understanding of

domestic violence, especially as it related to children and young

people, like the first group they considered domestic violence only

of concern when children or young people saw physical violence

between their parents/carers. They had only minimal understanding of the broader implications of living in a household where

there is domestic violence. These two groups struggled to identify

domestic violence unless it was very obvious. The third group

demonstrated a more comprehensive knowledge of domestic

violence and the effects of living in a household where domestic

violence is present. These practitioners had confidence in assessing the impact of domestic violence. They frequently saw women

as having the responsibility to protect their children. The fourth

group also had a comprehensive knowledge of domestic violence

especially as it related to children and young people. For these practitioners, the womans and childrens safety was inter-dependent.

The largest numbers of practitioners fell into the second (eight)

and third groups (six) with three each in the first and fourth groups.

Understanding of domestic violence and their view about whether

it constituted a child protection issue were highly influential in how

these practitioners responded to referrals of child abuse based

primarily on domestic violence.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

Domestic Violence in New South Wales, Australia

319

Implications for Policy and Practice

The inclusion of domestic violence as a discrete criterion in child

protection appears to have created a milieu in which the technical

process associated with the recording of domestic violence has

become the focus of the child protection statutory authority response. Whilst the data indicate that increasing numbers of child

abuse referrals contain domestic violence as a factor in the abuse,

there appears to be no concomitant perceptual or service delivery

response.

Despite the frequency of links between domestic violence and

child abuse having been established (see for example Radford and

Hester, 2006, pp. 5456), this research shows that even though

domestic violence is included as an official form of child abuse, it

is dealt with differently and treated less seriously as a risk of harm

compared to other forms of abuse and neglect. The serious consequences that living with domestic violence can have on children

and their mothers has been confirmed by research undertaken in

numerous countries in the western world (Mullender et al., 2002;

Stanley et al., 2003; Breckenridge and Ralfs, 2006; Radford and

Hester, 2006; Humphreys and Stanley, 2006; Houghton, 2006). In

NSW this is evident in the NSW Child Death Review Team reports

and in the NSW Ombudsmans Reviewable Deaths Annual Reports

(NSW Ombudsman, 2004, 2005, 2006). In the 200001 CDRT

report, 21 children in NSW died as a consequence of abuse or

neglect or suspicious of abuse and neglect. There was a history of

domestic violence in 18 of the families of these children (NSW

Child Death Review Team, 2001). In the 2001 02 report, a similar

number of children died as a consequence of abuse or neglect

or suspicious of abuse and neglect, with 17 having a history of

domestic violence (NSW Child Death Review Team, 2002). In the

NSW Ombudsmans first Reviewable Deaths Annual Report 2003

2004, there were 161 reviewable deaths over the period January

2003 to June 2004. Of these, there were 96 reports of risk of harm

related to domestic violence. The report states:

Seven of the children whose deaths were reviewed in detail had been

reported to DoCS for concerns about exposure to domestic violence. In none

of these cases did we find any evidence of DoCS making referrals to external

agencies specialising in support of victims of domestic violence or agencies

specialising in treatment of perpetrators. (NSW Ombudsman, 2004, p. 62.)

We argue that contact with or referral to a health, community

or human service professional creates a possibility for women,

children and young people who live with domestic violence to be

offered services and support which may enable them to begin to

make changes in their lives. The importance of offering access to

such services is supported in research undertaken by Mullender and

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Be no concomitant

perceptual or

service delivery

response

Services and

support which

may enable them

to begin to make

changes in their

lives

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

320

Living with

domestic violence

was not

conceptualised as a

real child protection

issue

The gendered

nature of domestic

violence, power

and control issues

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Irwin and Waugh

colleagues (2002) in which children and their mother were interviewed about their experiences of living with domestic violence.

The research showed that listening to children and supporting

mothers to connect with their children are key functions of

agencies, creating opportunities to understand and enhance safety.

Irrespective of the controversy around the mandatory reporting

of domestic violence to the NSW statutory child protection agency,

referrals to DoCS create this same possibility. In this study however, the opportunity for ongoing intervention was rarely realised.

Children, young people and their mothers who were exposed to

domestic violence and referred to the statutory child protection

authority were unlikely to receive protective intervention, support

or referral to other agencies. Was this because of an overwhelming

increase in the numbers of notifications combined with statutory

practitioners limited understandings about the complexities surrounding domestic violence, resulting in less priority given to

investigating such notifications? Was it because of the complexity

of the situations with domestic violence often co-occurring with

other with other forms of abuse such as parental drug and alcohol

misuse and /or mental health concerns? For whatever reason, the

opportunity for intervention was lost. The women and their

children received inadequate or no risk assessments, limited referral and support, sporadic or no follow up or referral to agencies

largely because, for whatever reason, living with domestic violence

was not conceptualised as a real child protection issue. Despite

the NSW government being committed to a co-ordinated and

comprehensive response to promote the protection of children

and young people and their families, this was only rarely evident

in the referrals based on domestic violence. All too frequently the

chances to provide women and their children with support were lost.

We are arguing for a response that is sympathetic to women

and their children who live with domestic violence, linking them

with supportive and empowering services rather than one that

ignores the impact of violence, is punitive and blaming of women

for not protecting their children. Protecting children from harm is

not the responsibility for only one agency, it requires collaboration

from both public and community based agencies working effectively together to reduce the risks to children (see for example and

Stanley and Humphreys, 2006). In a review of six research studies

on domestic violence, Radford and Hester (2006) conclude that

if there is to be positive practice with children and mothers who

live with domestic violence, then a multi-agency approach is

crucial and has to underpin any work by welfare or other agencies

engaged in work with families experiencing domestic violence

(Radford and Hester, 2006, p. 149). Child protection services need

to understand the gendered nature of domestic violence, power

and control issues and ensure a supportive, positive rather than a

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

Domestic Violence in New South Wales, Australia

321

punitive and mother-blaming approach (Radford and Hester, 2006,

p. 149).

Conclusion

Many women, children and young people who live with domestic

violence do have contact with health and human service agencies

so there are genuine opportunities to intervene and provide services and support. Unless child protection practitioners and policy

makers move beyond the rhetoric to take domestic violence seriously and develop relevant training and risk assessment processes

that account for the specific needs of children and young people who

live with domestic violence, effective services to children, young

people and their mothers will remain limited. We need to ensure

that practitioners work collaboratively to pick up the cues and

respond to domestic violence to end the kind of experience

described by an eight year participant in the research who said:

No one helped my mum.

No one helped my

mum

Acknowledgements

This research project was sponsored by a grant from the Australian

Research Council, Barnardos Australia and the NSW DoCS. The

research was undertaken with approval from the NSW DoCS.

However, the conclusions drawn from the study constitute the

views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view

of the NSW Government, The Minister for Community Services,

or the Department. The authors acknowledge the contribution of

the late Dr Marie Wilkinson to this project.

References

Breckenridge J, Ralfs C. 2006. Point of contact front-line workers responding

to children living with domestic violence. In Domestic Violence and Child

Protection: New Directions for Practice, Humphreys C, Stanley N (eds).

Jessica Kingsley Publications: London; 110 123.

Calder M, Harold G, Howarth E. 2004. Children Living with Domestic Violence.

Towards a Framework for Assessment and Intervention. Russell House Publishing: Lyme Regis, Dorset.

Edleson J. 2001. Studying the Co-Occurrence of Child Maltreatment and

Domestic Violence in Families. In Graham-Bermann S, Edleson J (eds).

Domestic Violence in the Lives of Children. American Psychological Association: Washington, D.C. 91110.

Houghton C. 2006. Listen Louder: Working with Children and Young People.

In Humphreys C, Stanley N (eds). Domestic Violence and Child Protection:

New Directions for Practice. Jessica Kingsley: London. 8294.

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

322

Irwin and Waugh

Humphreys C. 1993. The Referral of Families Associated with Child Sexual

Assault. New South Wales Department of Community Services: Sydney.

Humphreys C, Stanley N. 2006. Introduction. In Humphreys C, Stanley N (eds).

Domestic Violence and Child Protection: New Directions for Practice.

Jessica Kingsley: London; 9 16.

Irwin J, Wilkinson M. 1997. Women, children and domestic violence. Women

Against Violence: An Australian Feminist Journal 3: 15 22.

Irwin J, Waugh F, Wilkinson M. 2002. Domestic Violence and Child Protection

A research report. University of Sydney: Sydney.

Jaffe P, Wolfe D, Wilson S. 1990. Children of battered women. Sage: Newbury

Park.

James M. 1994. Domestic violence as a form of child abuse: Identification

and prevention. Issues in Child Abuse Prevention. Child Protection

Clearinghouse: Melbourne.

Jourles E, McDonald R, Norwood W, Ezell E. 2001. Issues and controversies

in documenting the prevalence of childrens exposure to domestic violence.

In Graham-Bermann S, Edleson J (eds). Domestic Violence in the Lives of

Children. American Psychological Association: Washington, D.C.; 1334.

Laing L. 2000. Children, young people and domestic violence. Australian

Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse: Kensington.

Mullender A, Hague G, Imam U, Kelly L, Malos E, Regan L. 2002. Childrens

Perspectives on Domestic Violence. Sage: London.

NSW Child Death Review Team. 2001. Annual Report 20002001, NSW Commission for Children and Young People: Sydney.

NSW Child Death Review Team. 2002. Annual Report 20012002, NSW Commission for Children and Young People: Sydney.

NSW Government. 1998. Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection)

Act 1998, No. 157, NSW Government Printer; Sydney.

NSW Ombudsman. 2004. Reviewable Child Deaths Annual Report 20032004.

NSW Ombudsman: Sydney.

NSW Ombudsman. 2005. Reviewable Child Deaths Annual Report 20042005.

NSW Ombudsman: Sydney.

NSW Ombudsman. 2006. Reviewable Child Deaths Annual Report 20052006.

NSW Ombudsman: Sydney.

OKeefe M. 1995. Predictors of child abuse in maritally violent families. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 10: 325.

Perrin T. 1992. NSW Department of Community Services, Staff Climate Survey

Final Report. NSW Department of Community Services: Sydney.

Radford L, Hester M. (2006) Mothering Through Domestic Violence. Jessica

Kingsley: London.

Stanley N, Humphreys C. 2006. Multi-agency and multi-disciplinary work:

Barriers and Opportunities. In C Humphreys, N Stanley (eds). Domestic

Violence and Child Protection: New Directions for Practice. Jessica

Kingsley: London, 36 50.

Stanley N, Penhale B, Riordan D, Barbour R, Holden S. 2003. Child Protection

and Mental Health Services. Interprofessional responses to the needs of

mothers. The Policy Press: Bristol.

Waugh F. 1997. Policy in action: An exploration of practice by frontline workers

in New South Wales Department of Community Services in responding to

notifications of child emotional abuse. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of

Sydney.

Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Child Abuse Review Vol. 16: 311322 (2007)

DOI: 10.1002/car

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- ERO Opportunity Framing 11-3 PDFДокумент27 страницERO Opportunity Framing 11-3 PDFSamuel Gaétan75% (4)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Topic 11 To 14 Answer PDFДокумент11 страницTopic 11 To 14 Answer PDFSrinivasa Reddy SОценок пока нет

- Alberta Justice Communications, 2008Документ265 страницAlberta Justice Communications, 2008Stoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- The Social Life of EmotionsДокумент21 страницаThe Social Life of EmotionsStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- BootstrapДокумент1 страницаBootstrapStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- Heading h6 Is The Smallest.: HTML Stands For Hypertext Markup Language, and Is Used To Give A Webpage StructureДокумент4 страницыHeading h6 Is The Smallest.: HTML Stands For Hypertext Markup Language, and Is Used To Give A Webpage StructureStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- CSS TipsДокумент7 страницCSS TipsStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- Copil/violenta DomesticaДокумент15 страницCopil/violenta DomesticaStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- Testingexperience01 09 CollinoДокумент8 страницTestingexperience01 09 CollinoStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- Children and Domestic ViolenceДокумент2 страницыChildren and Domestic ViolenceStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- Testingexperience01 09 CollinoДокумент8 страницTestingexperience01 09 CollinoStoica Ioana CristinaОценок пока нет

- PWC The Use of Spreadsheets Considerations For Section 404 of The Sarbanes Oxley Act PDFДокумент9 страницPWC The Use of Spreadsheets Considerations For Section 404 of The Sarbanes Oxley Act PDFbserОценок пока нет

- Disaster Management (Role of Social Workers) 1Документ20 страницDisaster Management (Role of Social Workers) 1Neethu AbrahamОценок пока нет

- Inbound 5517148729659412571Документ9 страницInbound 5517148729659412571Rabeh BàtenОценок пока нет

- OGP 434-01 RiskДокумент40 страницOGP 434-01 RiskDavid BarreraОценок пока нет

- DRRR DLL 1 WeekДокумент6 страницDRRR DLL 1 WeekMichael Jhon Funelas MinglanaОценок пока нет

- Capital Budgeting Practices in Developing CountriesДокумент19 страницCapital Budgeting Practices in Developing CountriescomaixanhОценок пока нет

- 02 Security-Management-Module UEL-CN-70149089Документ18 страниц02 Security-Management-Module UEL-CN-70149089shirleyn22225Оценок пока нет

- FCCL Ar 22 1Документ288 страницFCCL Ar 22 1i201692 Shafeen AhmadОценок пока нет

- Decision-Making Behavior and Risk Perception of CHДокумент18 страницDecision-Making Behavior and Risk Perception of CHManuel CerveroОценок пока нет

- Risk Management HandbookДокумент32 страницыRisk Management HandbookMorais JoseОценок пока нет

- Lesson 4: Practice Occupational Safety and Health ProceduresДокумент6 страницLesson 4: Practice Occupational Safety and Health ProceduresBrenNan Channel100% (1)

- The Next-Generation Investment Bank - The Boston Consulting Group PDFДокумент13 страницThe Next-Generation Investment Bank - The Boston Consulting Group PDFlib_01Оценок пока нет

- BBS - Risk - Assessment UpdatedДокумент2 страницыBBS - Risk - Assessment UpdatedSuraj RawatОценок пока нет

- Application-Portfolio-Governance - Software AgДокумент24 страницыApplication-Portfolio-Governance - Software AgRohitОценок пока нет

- Risk and Resilience in The Era of Climate Change Vinod Thomas All ChapterДокумент77 страницRisk and Resilience in The Era of Climate Change Vinod Thomas All Chapterdena.joseph863100% (6)

- (03a) LHN Offer Document (Clean) PDFДокумент614 страниц(03a) LHN Offer Document (Clean) PDFInvest StockОценок пока нет

- Glykas 2010 Fuzzy Cognitive MapsДокумент435 страницGlykas 2010 Fuzzy Cognitive MapslupblaОценок пока нет

- LR004WS03 - Libacq - Final Feasibility Report - REV01Документ151 страницаLR004WS03 - Libacq - Final Feasibility Report - REV01Zoran KostićОценок пока нет

- Decision TMA2 AnswerДокумент5 страницDecision TMA2 AnswerYosef DanielОценок пока нет

- Ready Pack Information SheetДокумент2 страницыReady Pack Information SheetSatish HiremathОценок пока нет

- Cash-Flow Reporting Between Potential Creative Accounting Techniques and Hedging Opportunities Case Study RomaniaДокумент14 страницCash-Flow Reporting Between Potential Creative Accounting Techniques and Hedging Opportunities Case Study RomaniaLaura GheorghitaОценок пока нет

- WHO Good Manufacturing Practices For Excipients Used in Pharmaceutical ProductsДокумент41 страницаWHO Good Manufacturing Practices For Excipients Used in Pharmaceutical ProductssajimarsОценок пока нет

- Chevron Corporate Responsability Report 2011Документ52 страницыChevron Corporate Responsability Report 2011CSRmedia.ro NetworkОценок пока нет

- ISO 22301 ChecklistДокумент3 страницыISO 22301 ChecklistAkbar AnsariОценок пока нет

- I. Some Risks of Poor Corporate GovernanceДокумент3 страницыI. Some Risks of Poor Corporate GovernanceTrần Ánh NgọcОценок пока нет

- Risk Assessment ISO31000Документ61 страницаRisk Assessment ISO31000André Santos50% (2)

- UOB Risk Management 2Документ10 страницUOB Risk Management 2jariya.attОценок пока нет