Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Chalmers - Metametaphysics

Загружено:

Pokojni TozaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Chalmers - Metametaphysics

Загружено:

Pokojni TozaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Philosophy in Review XXX (2010), no.

David Chalmers, David Manley, Ryan Wasserman, eds.

Metametaphysics: New Essays on the Foundations of

Ontology.

Oxford: Oxford University Press 2009

529 pages

US$45.95 (paper ISBN 978-0-19-954600-8)

Metametaphysics is an excellent collection of papers about the nature and methodology of

metaphysics written by the subjects movers and shakers. It will be of great interest to

anyone enamored, repulsed, or mystified by metaphysics.

Metaphysics, especially ontology, enjoyed something of a renaissance a few

decades ago, at least when compared to the preceding anti-metaphysical currents of the

early 20th century. According to lore, this renaissance had two main causes. The first was

Quines alleged purification of ontology: Quine revived ontology by showing us how to

do it without indulging in the obscurities which so bothered his positivist predecessors,

such as Ayer and Carnap. But there remain questions about the accuracy of this lore and

what its legacy ought to be. Peter Van Inwagens essay articulates and defends Quines

alleged purification. Scott Soames critically examines the nature of the infamous debate

between Carnap and Quine, arguing that they were more closely allied than the lore

allows. Huw Price argues that Quines alleged revival of ontology has been vastly

overstated.

The second cause of metaphysics renaissance was the bold metaphysics of Saul

Kripke, David Lewis, David Armstrong, Kit Fine, and others in the last part of the 20th

century. These philosophers shamelessly invoked supposedly mysterious metaphysical

notions (such as possibility, necessity, essence, natural properties, truthmakers, and

grounding) and used them toward fruitful and ambitious philosophical ends. Along this

trajectory, Bob Hale and Crispin Wrights essay focuses on how the neo-Fregean project

uses abstraction principles (such as: the number of Fs = the number of Gs iff the Fs and

the Gs correspond one-to-one) to develop a Platonist view about numbers which avoids

its traditional epistemic pitfalls.

However, reading the essays in Metametaphysics gives one the impression that the

renaissances days are numbered. This is because most of the essays are each, in one way

or the other, concerned with addressing skepticism about metaphysics.

The essays by David Chalmers and Eli Hirsch each defend a broadly neoCarnapian view according to which answers to many (if not all) metaphysical questions

reflect little more than our choices about how to describe reality. The essays by Matti

Eklund, John Hawthorne, and Theodore Sider are direct responses to this view. Both

Eklund and Hawthorne, although in different ways and toward different ends, object that

173

Philosophy in Review XXX (2010), no. 3

neo-Carnapians must reject plausible semantic principles. Sider objects that reality has an

objective structure and that metaphysics strives to discover it.

The skeptical threats are manifested in other ways too. Karen Bennett, while

unsympathetic to neo-Carnapianism, nevertheless argues that creatures like us are poorly

suited to making metaphysical progress. Amie Thomasson rejects much of traditional

metaphysics as concerned with unanswerable questions, while favoring a revisionist

metaphysics combining conceptual analysis with empirical investigation. Stephen Yablo

argues that discourse which apparently carries ontological commitment is, in a peculiar

way, ontologically neutral and so ontological questions about the objects of that discourse

are factually defective.

The preoccupation with skeptical threats is partly just the playing out of the old

epic struggle between metaphysics and epistemology. But there also seems to be a more

specific culprit: the nearly universal endorsement of Quines conception of ontological

questions as quantificational questions (which, ironically, was supposed to have purified

ontology). For once Are Fs real? is purified as Is there at least one F?, then it can seem

that only two sensible methodologies emerge for answering such questions: (i) consult our

Moorean beliefs (Theres obviously a table there!); or (ii) consult our best science

(Physics only needs the particles, and not any table over and above them!). If (i), then it

seems that the answers to ontological questions are trivial and uninteresting; but if (ii),

then it seems that science, not metaphysics, provides the answers. So either metaphysics

trades in trivialities or is made obsolete by science. Thomas Hofwebers essay explicitly

concerns finding a place for metaphysics between this rock and hard place, and many of

the other essays are at least implicitly wary of this dilemma.

The long shadow skeptical doubts cast upon the essays in Metametaphysics might

easily give one the impression that metametaphysics is primarily concerned with

responding to skeptical challenges to metaphysics. But (fortunately) metametaphysics

isnt merely the epistemology of metaphysics. A few maverick contributors are more

focused on the metaphysics of metaphysics. This is especially evident in the way these

mavericks depart from various aspects of the Quinean orthodoxy mentioned earlier.

Many of the authors recognize the need to distinguish an ordinary metaphysicallyunloaded sense of the quantifiers from their serious metaphysically-loaded sense. But

Sider pushes this idea further by building upon Lewis notion of natural properties and

taking reality itself to have natural joints: objective structure which only the

metaphysically-loaded sense of the quantifier captures. Ontological questions are

quantificational questions; but only a special kind of quantificational question is an

ontological question. Kris McDaniel defends a revival of the outmoded distinction

between ways of being by arguing that Siders general notion of structure is really an

abstraction upon many particular notions of structure, each corresponding to a distinct

way of being.

174

Philosophy in Review XXX (2010), no. 3

One last maverick theme opposes contemporary metaphysics focus on ontology.

There are at least two reasons why it is thus focused: (i) Quines alleged purification of

ontology, and (ii) David Lewis tour de force of how an incredible ontology of possible

worlds provides broad philosophical payoffs. No wonder, then, that the only anthology

on metametaphysics is subtitled New Essays on the Foundations of Ontology!

Refreshingly, Jonathan Schaffer and Kit Fine buck this trend. While Schaffer

agrees with Quine that ontological questions are quantificational questions, he argues that

ontological questions just arent what metaphysics is really about. It is rather about what

is fundamental or prior (in the sense of being ontologically independent), as opposed to

what is derivative (in the sense of being ontologically dependent). More radically, Fine

rejects what all the other essays (implicitly or explicitly) endorse: the Quinean

assimilation of ontological questions to quantificational questions. Instead, Fine defends a

primitive metaphysical conception of reality which does not support construing

ontological questions quantificationally. Metaphysics is about what facts hold in reality

and how they ground those facts which do not. Ontology is just a (small) branch of this

larger project; it is the branch concerned with which objects the real facts are about.

The contributions of these mavericks seem to be the most refreshing and

interesting parts of Metametaphysics. It is unfortunate that they did not receive more

attention from the other contributors. For one example, Hofweber chastises Schaffer,

Fine, and others for making metaphysics an esoteric game playable only by members of

an elite club who claim to possess metaphysical concepts, such as fundamentality,

ground, and reality. Suspicions about these metaphysical concepts are thus taken to be a

reason to conceive of metaphysics without them. But perhaps that is to change the

subject. Perhaps the way to rein in metaphysics excesses of esotericism is not by

ignoring its distinctive but elusive concepts, but by confronting them head on.

In any case, its understandable that metaphysicians want to defend their

discipline, especially after feeling so much pressure from skeptics for so long. But it

seems as if the skeptics have been allowed to set the terms of the debate. Perhaps some

more mavericks are needed.

Nevertheless, this is a first-rate anthology of first-rate essays. These papers,

together with David Manleys useful introduction, offer an accurate snapshot of the

current state of metametaphysics. Not only that, they also give us an idea where

metametaphysics is headed.

Michael J. Raven

University of Victoria

175

Вам также может понравиться

- MercerДокумент33 страницыMercersadir16100% (4)

- Injection Machine RobotДокумент89 страницInjection Machine Robotphild2na250% (2)

- Critical Scientific Realism: AbstractДокумент245 страницCritical Scientific Realism: AbstractderrickbartОценок пока нет

- Deep Beauty - Understanding The Quantum World Through Mathematical InnovationsДокумент488 страницDeep Beauty - Understanding The Quantum World Through Mathematical InnovationsRobert Klinzmann100% (3)

- Practice For The CISSP Exam: Steve Santy, MBA, CISSP IT Security Project Manager IT Networks and SecurityДокумент13 страницPractice For The CISSP Exam: Steve Santy, MBA, CISSP IT Security Project Manager IT Networks and SecurityIndrian WahyudiОценок пока нет

- Better Typing and Dictating PracticesДокумент7 страницBetter Typing and Dictating PracticesDiyansh JainОценок пока нет

- Does Physics Answer Metaphysical Questions?Документ23 страницыDoes Physics Answer Metaphysical Questions?Jaime Feliciano HernándezОценок пока нет

- Does Physics Answer Metaphysical Questions?Документ23 страницыDoes Physics Answer Metaphysical Questions?Maristela RochaОценок пока нет

- Project Muse 820393Документ3 страницыProject Muse 820393zshuОценок пока нет

- The Shaky Game +25, Or: On Locavoracity: Laura RuetscheДокумент18 страницThe Shaky Game +25, Or: On Locavoracity: Laura RuetscheGilson OlegarioОценок пока нет

- Metaphysics A Guided Tour For Beginners PDFДокумент153 страницыMetaphysics A Guided Tour For Beginners PDFAsif Akbar KhanОценок пока нет

- The Scientific Realism DebateДокумент16 страницThe Scientific Realism Debate25061950Оценок пока нет

- Nontraditional Arguments For Theism: Chad A. McintoshДокумент14 страницNontraditional Arguments For Theism: Chad A. McintoshRayan Ben YoussefОценок пока нет

- Rovelli - Physics Needs Philosophy, Philosophy Need PhysicsДокумент11 страницRovelli - Physics Needs Philosophy, Philosophy Need PhysicsJúnior BaracatОценок пока нет

- What Is The Relation Between Science and PhilosophyДокумент25 страницWhat Is The Relation Between Science and PhilosophyAbelooo OoОценок пока нет

- Apologetics Press - 7 Reasons The Multiverse Is Not A Valid Alternative To God (Part 2)Документ9 страницApologetics Press - 7 Reasons The Multiverse Is Not A Valid Alternative To God (Part 2)Glenn VillegasОценок пока нет

- Zhu Xi, MetaphsicsДокумент15 страницZhu Xi, MetaphsicsNicholas Sena HusengОценок пока нет

- Física y FilosofíaДокумент11 страницFísica y FilosofíaMichel tОценок пока нет

- Metaphysics Between The Sciences and Philosophies of ScienceДокумент17 страницMetaphysics Between The Sciences and Philosophies of Scienceperception888Оценок пока нет

- Olsen 258378 PDFДокумент14 страницOlsen 258378 PDFGerimy Bernardino BacsalОценок пока нет

- H F Empirismo Lógico9 PDFДокумент23 страницыH F Empirismo Lógico9 PDFPelayo Baquero SánchezОценок пока нет

- Physics of The World Soul Whitehead and CosmologyДокумент65 страницPhysics of The World Soul Whitehead and CosmologyMJ Qa100% (1)

- The Emergence of Subtle Organicism: Michael Towsey Queensland University of Technology AustraliaДокумент28 страницThe Emergence of Subtle Organicism: Michael Towsey Queensland University of Technology Australiafireworkli023Оценок пока нет

- Does Science Need Philosophy?Документ4 страницыDoes Science Need Philosophy?Luluwa MurtazaОценок пока нет

- Scientific MetaphysicsДокумент6 страницScientific MetaphysicsVakiPitsiОценок пока нет

- (PE) (Taylor) Probing The Limits of Reality - The Metaphysics in Science FictionДокумент7 страниц(PE) (Taylor) Probing The Limits of Reality - The Metaphysics in Science Fictionjcb1961Оценок пока нет

- Review of The Devil's DelusionДокумент7 страницReview of The Devil's Delusiontoypom0% (1)

- Kant Metaphysics 1Документ58 страницKant Metaphysics 1Quantum SaudiОценок пока нет

- Brian J. Shanley, O.P. - Analytical ThomismДокумент14 страницBrian J. Shanley, O.P. - Analytical ThomismCaio Cézar SilvaОценок пока нет

- MichelWeber Much Ado 2011Документ8 страницMichelWeber Much Ado 2011infochromatikaОценок пока нет

- (Posthumanities) Isabelle Stengers - Translated by Robert Bononno-Cosmopolitics I-Univ of Minnesota Press (2010) PDFДокумент307 страниц(Posthumanities) Isabelle Stengers - Translated by Robert Bononno-Cosmopolitics I-Univ of Minnesota Press (2010) PDFMateus Thomaz100% (1)

- Physics Needs Philosophy. Philosophy Needs Physics.: Carlo RovelliДокумент9 страницPhysics Needs Philosophy. Philosophy Needs Physics.: Carlo RovelliflyredeagleОценок пока нет

- Discontinuous MaterialismДокумент9 страницDiscontinuous Materialismbenjaminburgoa521Оценок пока нет

- Justifying Sociological Knowledge From Realism To InterpretationДокумент30 страницJustifying Sociological Knowledge From Realism To InterpretationGallagher RoisinОценок пока нет

- Metaphysics Investigates Principles of Reality Transcending Those of Any Particular ScienceДокумент1 страницаMetaphysics Investigates Principles of Reality Transcending Those of Any Particular ScienceRansel Fernandez VillaruelОценок пока нет

- Thomism and The Formal Object of LogicДокумент39 страницThomism and The Formal Object of Logicpaco100% (1)

- Are There Genuine Mathematical Explanations of Physical Phenomena - Alan BakerДокумент17 страницAre There Genuine Mathematical Explanations of Physical Phenomena - Alan BakerFelipe100% (1)

- Metaphysical Deja Vu Hacking and Latour On Science Studies and Metaphysics - Martin Kusch 2002Документ9 страницMetaphysical Deja Vu Hacking and Latour On Science Studies and Metaphysics - Martin Kusch 2002Ali QuisОценок пока нет

- Adrian Johnston - Prolegomena To Any Future Materialism. The Outcome of Contemporary French Philosophy (Vol. 1) PDFДокумент265 страницAdrian Johnston - Prolegomena To Any Future Materialism. The Outcome of Contemporary French Philosophy (Vol. 1) PDFHernán Noguera Hevia100% (4)

- Bridging The Gap Between Science and MetДокумент19 страницBridging The Gap Between Science and Mettlhnabb2016Оценок пока нет

- Special Issue of Spontaneous Generations PDFДокумент222 страницыSpecial Issue of Spontaneous Generations PDFgerman guerreroОценок пока нет

- MetaphysicsДокумент16 страницMetaphysicsmanoj kumar100% (1)

- Metaphysics - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFДокумент18 страницMetaphysics - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFRodnyXSilvaОценок пока нет

- Mathematical Realism and The Impossible PDFДокумент26 страницMathematical Realism and The Impossible PDFkronstadtОценок пока нет

- Stanley L Jaki On Thomistic MetaphysicsДокумент35 страницStanley L Jaki On Thomistic MetaphysicsCarolina del Pilar Quintana NuñezОценок пока нет

- Metaphysics A Guided TourДокумент154 страницыMetaphysics A Guided Tourv͓̽o͓̽l͓̽p͓̽e͓̽ ͓̽m͓̽a͓̽r͓̽r͓̽o͓̽n͓̽e͓̽ ͓̽v͓̽e͓̽l͓̽o͓̽c͓̽e͓̽Оценок пока нет

- Pedrinho Cheração SaudeДокумент28 страницPedrinho Cheração SaudePablo DumontОценок пока нет

- MetaphysicsДокумент158 страницMetaphysicsjanistroques100% (3)

- Metaphysics - WikipediaДокумент27 страницMetaphysics - WikipediaHamilton Dávila CórdobaОценок пока нет

- Deep Beauty Understanding The QuantumДокумент488 страницDeep Beauty Understanding The QuantumKanin FaanОценок пока нет

- 330 Pages. $19.95.: Five Proofs of The Existence of God. by Edward Feser. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2017Документ7 страниц330 Pages. $19.95.: Five Proofs of The Existence of God. by Edward Feser. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2017Μιλτος ΘεοδοσιουОценок пока нет

- Philosophy of Science PaperДокумент3 страницыPhilosophy of Science Papermarc abellaОценок пока нет

- Truthmaker Ontology CorrectedДокумент275 страницTruthmaker Ontology CorrectedEma BrajkovicОценок пока нет

- Quine and Ontology - Oswaldo ChateaubriandДокумент34 страницыQuine and Ontology - Oswaldo ChateaubriandMarlon Henrique100% (1)

- BUNGE, Mario (1981) - Scientific Materialism (Reidel, Dordrecht) PDFДокумент220 страницBUNGE, Mario (1981) - Scientific Materialism (Reidel, Dordrecht) PDFenlamadrehijo100% (1)

- Not a Chance: God, Science, and the Revolt against ReasonОт EverandNot a Chance: God, Science, and the Revolt against ReasonРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (15)

- Comments on Richard Colledge’s Essay (2021) "Thomism and Contemporary Phenomenological Realism"От EverandComments on Richard Colledge’s Essay (2021) "Thomism and Contemporary Phenomenological Realism"Оценок пока нет

- Universe 05 00113 v2Документ9 страницUniverse 05 00113 v2Yuri YuОценок пока нет

- The Return of Radical ImpericismДокумент8 страницThe Return of Radical ImpericismFlorin CiocanuОценок пока нет

- Scientific Realism in The Age of String TheoryДокумент34 страницыScientific Realism in The Age of String TheorysonirocksОценок пока нет

- Multiple Universes Have Been Hypothesized inДокумент3 страницыMultiple Universes Have Been Hypothesized inStormОценок пока нет

- The Renaissance of Epistemology 1914 194Документ11 страницThe Renaissance of Epistemology 1914 194michaeldavid0200Оценок пока нет

- Tautological Oxymorons: Deconstructing Scientific Materialism:An Ontotheological ApproachОт EverandTautological Oxymorons: Deconstructing Scientific Materialism:An Ontotheological ApproachОценок пока нет

- ODR-1 PCBДокумент1 страницаODR-1 PCBPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- ODR 1 SchematicДокумент1 страницаODR 1 SchematicPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- ODR 1 LayoutДокумент1 страницаODR 1 LayoutPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- ODR 1 LayoutДокумент1 страницаODR 1 LayoutPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- ODR-1 SchematicДокумент1 страницаODR-1 SchematicPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- ODR-1 PCBДокумент1 страницаODR-1 PCBPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

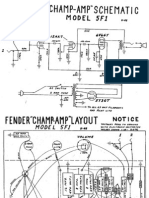

- Champ 5f1Документ2 страницыChamp 5f1Vincenzo MalerbaОценок пока нет

- Heidegger Deleuze Sholtz LawlorДокумент10 страницHeidegger Deleuze Sholtz LawlorscribdkfcОценок пока нет

- Godel Free WillДокумент24 страницыGodel Free WillPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- 2204 ModsДокумент3 страницы2204 ModsPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- Nietzsche's PositivismДокумент43 страницыNietzsche's Positivismgerti09Оценок пока нет

- Ontology and AxiologyДокумент5 страницOntology and AxiologyPokojni TozaОценок пока нет

- Fabrication of Mortar Mixer and CHB Filler PumpДокумент15 страницFabrication of Mortar Mixer and CHB Filler PumpRenjo Kim VenusОценок пока нет

- Class 10 Mid Term Syllabus 202324Документ4 страницыClass 10 Mid Term Syllabus 202324Riya AggarwalОценок пока нет

- 14-) NonLinear Analysis of A Cantilever Beam PDFДокумент7 страниц14-) NonLinear Analysis of A Cantilever Beam PDFscs1720Оценок пока нет

- Effects of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Education On Childhood Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Rural Dembiya, Northwest Ethiopia An Uncontrolled (2019) Zemi PDFДокумент8 страницEffects of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Education On Childhood Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Rural Dembiya, Northwest Ethiopia An Uncontrolled (2019) Zemi PDFKim NichiОценок пока нет

- Rajesh Raj 2015Документ13 страницRajesh Raj 2015Habibah Mega RahmawatiОценок пока нет

- Ontologies For Location Based Services Quality Enhancement: The Case of Emergency ServicesДокумент8 страницOntologies For Location Based Services Quality Enhancement: The Case of Emergency Serviceskhairul_fajar_3Оценок пока нет

- Module 1: Introduction To VLSI Design Lecture 1: Motivation of The CourseДокумент2 страницыModule 1: Introduction To VLSI Design Lecture 1: Motivation of The CourseGunjan JhaОценок пока нет

- Performance in MarxismДокумент226 страницPerformance in Marxismdeanp97Оценок пока нет

- Module 2Документ4 страницыModule 2Amethyst LeeОценок пока нет

- Genogram and Eco GramДокумент5 страницGenogram and Eco GramGitichekimОценок пока нет

- ME Math 8 Q1 0101 PSДокумент22 страницыME Math 8 Q1 0101 PSJaypee AnchetaОценок пока нет

- Sequential Circuit Description: Unit 5Документ76 страницSequential Circuit Description: Unit 5ramjidr100% (1)

- 11 Technical Analysis & Dow TheoryДокумент9 страниц11 Technical Analysis & Dow TheoryGulzar AhmedОценок пока нет

- The Scientific Method Is An Organized Way of Figuring Something OutДокумент1 страницаThe Scientific Method Is An Organized Way of Figuring Something OutRick A Middleton JrОценок пока нет

- Notes On Guenter Lee PDEs PDFДокумент168 страницNotes On Guenter Lee PDEs PDF123chessОценок пока нет

- A Presentation ON Office Etiquettes: To Be PresentedДокумент9 страницA Presentation ON Office Etiquettes: To Be PresentedShafak MahajanОценок пока нет

- Discussion Lab RefrigerantДокумент3 страницыDiscussion Lab RefrigerantBroAmir100% (2)

- 6 Biomechanical Basis of Extraction Space Closure - Pocket DentistryДокумент5 страниц6 Biomechanical Basis of Extraction Space Closure - Pocket DentistryParameswaran ManiОценок пока нет

- Build Web Application With Golang enДокумент327 страницBuild Web Application With Golang enAditya SinghОценок пока нет

- 2 The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility On Firms Financial PerformanceДокумент20 страниц2 The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility On Firms Financial PerformanceFam KhanОценок пока нет

- The Advanced Formula For Total Success - Google Search PDFДокумент2 страницыThe Advanced Formula For Total Success - Google Search PDFsesabcdОценок пока нет

- CalibrationДокумент9 страницCalibrationLuis Gonzalez100% (1)

- Second Form Mathematics Module 5Документ48 страницSecond Form Mathematics Module 5Chet AckОценок пока нет

- EnMS. MayДокумент7 страницEnMS. MayRicky NoblezaОценок пока нет

- Building and Environment: Edward NGДокумент11 страницBuilding and Environment: Edward NGauliaОценок пока нет

- Filed: Patrick FisherДокумент43 страницыFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет