Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Only G-D Is Unblemished

Загружено:

outdash2Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Only G-D Is Unblemished

Загружено:

outdash2Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Parshat Emor

13 Iyar, 5776/May 21, 2016

Vol. 7 Num. 34

This issue of Toronto Torah is sponsored by Esther and Craig Guttmann and Family

in memory of Beila Chana bat Chaim Baruch zl

Only G-d is Unblemished

For any man in whom there is a

blemish shall not approach: a man who

is blind or lame or whose nose has no

bridge, or who has one limb longer than

the other; or in whom there will be a

broken leg or a broken arm (Artscroll

translation of Vayikra 21:18-19)

Strangely, the Torah prohibits

kohanim exhibiting certain physical

defects from serving in the Beit

haMikdash. Excluding a physically

marred priest was not unusual for the

ancient Near East (This Abled Body,

pg. 26), but it seems inconsistent with

the Torahs broad messages regarding

the relative unimportance of physical

perfection.

Our greatest prophet, Moshe, the

source of our Torah and the closest

confidante of G-d, identified himself

as having a speech defect, and G-d did

not choose to heal him. (Shemot 4)

When the prophet Shemuel was sent

to select a king, and he was impressed

by a candidates physical form, G-d

rebuked him, Human beings see with

their eyes, but G-d sees the

heart. (Shemuel I 16:7) The Talmud

records a story of a man who was

insulted as ugly, and it approves of his

response, Go tell the Craftsman who

made me. (Taanit 20b) Torah and

tradition render absurd the idea that

there is any inferiority in, or any

Divine rejection of, a human being

whose form is damaged or incomplete.

Further: the demand for physical

perfection hardly guaranteed a proper

priesthood. The ranks of

unblemished priests included Chofni

and Pinchas, who abused their power

in control of the Mishkan; the high

priest Evyatar supported Adoniyahus

coup; the descendants of the priestly

Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner

Chashmonaim abused their power and

fell in with the Greeks; and the heretical

Sadducees claimed lineage from the

high priest Tzaddok.

We must also realize that exclusion of

people with physical challenges runs

counter to the respectful and protective

approach to the vulnerable trumpeted

throughout the Torah. How could the

Torah, which inveighs incessantly

against abuse of the week, perpetuate a

stigma regarding people who are blind,

lame, or suffer broken limbs?

One explanation is that the Torah is

concerned about popular perception of

the Beit haMikdash and its service. As

Sefer haChinuch (275) suggests, if [the

priest] is of deficient form and unusual

limbs, then even if he is righteous in his

ways, his deeds will still not be found as

positive in the eyes of his beholders.

This rationale is difficult, though; in

other areas of religious practice the

Torah harshly condemns weaknesses of

the human psyche, including hedonism

and miserliness. Imagine the lesson had

the Torah explicitly required the

inclusion of priests who exhibited

physical defects!

We might understand the exclusion of

the challenged kohen by recognizing

that physical defects are acceptable for

kings, sages, prophets and judges. In

every arena of Jewish life, public and

private, we promote respect for every

individual, regardless of physical

challenges; only regarding the kohen is

the law different. Perhaps this is

because the kohen who serves in the

Beit haMikdash is not viewed as a

human being at all; rather, the kohen is

a representative of G-d. [See Yoma 19a

and Kiddushin 23b.] Indeed, the

prophet Malachi identifies the kohen as

an angel of G-d. (Malachi 2:7)

There are two categories of success: the

easy victory, and the triumph over

adversity. For human beings, the latter

may be the greater achievement; as

Pirkei Avot 5:23 says, The reward is

commensurate with the pain endured.

Therefore, our role models king, sage,

prophet and judge include human

beings who struggle with, and

overcome, physical obstacles. The

kohen, though, represents G-d, for

whom there is neither obstacle nor

struggle, and in whom no defect can be

perceived. The Divine agent, like his

Master, must represent success without

challenge.

The unblemished kohen, inhabiting the

Beit haMikdash of G-d, is not a role

model for us. We are all incomplete and

challenged in some way, and therefore

our ideal role models are other

challenged human beings. We would be

criminally foolish if we failed to value

the role model in every human being,

recognizing the unique personalities,

talents and contributions of people who

triumph over all manner of adversity.

When we gaze upon the representatives

of G-d, let us see a world in which

success comes easily. But when we ask

ourselves who we wish to become, let us

look upon the blind or lame, the one

with the broken leg or broken arm.

These are our heroes, and from them we

will learn success.

[For other suggestions regarding the

exclusion of priests with physical

blemishes, see Toronto Torah 4:29 and

6:31.]

torczyner@torontotorah.com

OUR BEIT MIDRASH

ROSH BEIT MIDRASH

RABBI MORDECHAI TORCZYNER

SGAN ROSH BEIT MIDRASH

RABBI JONATHAN ZIRING

AVREICHIM RABBI DAVID ELY GRUNDLAND, RABBI YISROEL MEIR ROSENZWEIG

CHAVERIM DAR BARUCHIM, YEHUDA EKLOVE, URI FRISCHMAN, DANIEL GEMARA,

MICHAEL IHILCHIK, RYAN JENAH, SHIMMY JESIN, CHEZKY MECKLER, ZACK MINCER,

JOSH PHILLIP, JACOB POSLUNS, ARYEH ROSEN, SHLOMO SABOVICH, EZRA SCHWARTZ,

ARIEL SHIELDS, DAVID SUTTNER, DAVID TOBIS

We are grateful to

Continental Press 905-660-0311

Book Review: Machzor for Yom haAtzmaut / Yom Yerushalayim

Koren Machzor for Yom HaAtzmaut

and Yom Yerushalayim

Koren, 2014

Note: This author was a research

assistant for the Machzor.

The Controversy

P r od uci n g a ma ch z or for Yom

HaAtzmaut and Yom Yerushalayim is

inherently controversial, even among

Religious Zionists. As Matthew Miller

notes in the publishers preface, while

the Chief Rabbinate of Israel instituted

special prayers for these days, and it is

on the basis of those suggestions that

Koren Publ i she r s a rr an ged the

machzor, many Religious Zionists

opposed such liturgical changes. Most

prominently, Rabbi Joseph B.

Soloveitchik, though famously a

Religious Zionist and President of World

Mizrachi - the organization which

sponsored the machzor - was generally

very conservative regarding the

structure of the service[and] was

averse to changes in the traditional

o r d e r a n d c om p o si ti on of th e

prayers. (xiv). It is to the publishers

credit that they note, rather than shy

away from this in the introduction.

Miller notes that the goal of the

machzor was to organize various

prayers for those who would like to say

them, as it can give spiritual

expression and meaning to our

celebration and thanksgiving. (xiii) By

so doing, they hope to further

strengthen the bonds between the

Jewish communities in Israel and

English-speaking countries. (xiii-iv) As

they note, however, one can and

should celebrate, whether or not one

accepts the liturgical changes.

The Structure

The book is divided into two parts. The

first half is the machzor itself, which

includes liturgy for Yom HaZikaron,

Yom HaAtzmaut, and Yom

Yerushalayim. It includes

commentaries by Rabbi Dr. Binyamin

Lau (translated from the Hebrew Koren

Machzor), Rabbi Moshe Taragin, and

Dr. Yoel Rappel. The comments

include historical insights, inspiring

stories of Zionist leaders, and

commentary on chapters in Tanach

that are included in our prayers but

can shed light on what it means to be

a Religious Zionist.

The second half includes essays, some

of which are translations of essays

found in the Hebrew machzor, but

most of which were chosen for this

project. They include some newly

written articles, re-published English

articles, and newly-translated articles.

The authors come from a wide variety

613 Mitzvot: 509: Division of Labour

In describing the role of the kohanim, Moshe states, When a

Levite comes from his city of residence, from anywhere in

Israel, at his own desire, to the place that G-d will choose, he

shall serve in the name of Hashem his G-d, like his brethren

Levites who stand before G-d there. They shall eat portion for

portion, aside from that which was transacted by the

fathers. (Devarim 18:6-8) This teaches two complementary

lessons: (1) There were fixed shares and shifts arranged by

the earliest heads of the Levite families, and (2) Despite these

shifts, there were occasions when Levites chose to come

serve, spontaneously. [As explained by the Sages (Succah

55b), only those who came on their own to serve during the

three regel festivals received special portions.]

Sefer haChinuch counts the division of the Levites into shifts

as the Torahs 509th mitzvah, explaining that this is a

pragmatic strategy to ensure that responsible parties will be

in charge of the work of the Beit haMikdash each day. Each

shift is called a mishmar.

The Torah presents this mitzvah to Levites, but Rambam

(Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Klei haMikdash 4:6) explains that

the mitzvah is actually targeted only to the sub-set of Levites

who are kohanim. This is stated in a midrash (Sifri Shoftim

168) and implied in the Talmud (Taanit 27a), but it is also

evident in the Torahs own command regarding eating

portion for portion: Kohanim receive portions from the

offerings of the Beit haMikdash, and general Levites do not.

According to the Talmud (Taanit 27a), Moshe began the

division, the prophet Shemuel expanded it, and King David

Rabbi Jonathan Ziring

of Religious Zionist thinkers across the

globe from the past hundred years.

They range from Israeli rabbis of the

last generation, such as Rabbi Zvi

Yehuda Kook and Rabbi Shaul

Yisraeli, American rabbis of the last

generation, such as Rabbi Joseph

Soloveitchik, and current scholars

from across the world, Roshei Yeshiva

and public intellectuals such as Rabbi

Hershel Schachter, Rabbi Chaim

Druckman, Rabbi Dr. Lord Jonathan

Sacks, Dr. Erica Brown, and Dr. Yael

Zeigler. The goal of these essays is to

p r o v i d e p e r sp e c t i ve , h i s t o r i c ,

halakhic, and theologic (xv in essay

section), about the importance of these

days and the State of Israel in general.

The Benefit

For the English speaker who would

like to add prayers on these days, the

Machzor provides him with the

material and commentary, allowing

him to pray as so many Israelis do.

Even for those who are hesitant to

embrace sweeping liturgical change,

the latter half of the book can enhance

ones appreciation for the various

perspectives that exist within the

Religious Zionist world about the State

of Israel and its implications for our

religious lives.

jziring@torontotorah.com

Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner

added still more shifts. The later divisions are linked to the

distribution of tasks found in Divrei haYamim I 24-26.

General Levites also divided themselves into shifts (Divrei

haYamim I 24-26), but most authorities contend that this

was voluntary. Sefer haChinuch (#509) is nearly alone in

claiming that the biblical mitzvah includes the division of

general Levites.

In a related practice, the general Jewish population also

sent shifts, called maamadot, in the time of the Beit

haMikdash. A mishnah (Taanit 4:2) credits this to the early

prophets, which Rashi explains as Shemuel and King

David. The role of a maamad was to represent the broader

nation, as the kohanim and Levites conducted the daily

service in their name. They would fast, and hold special

public prayers and Torah readings. (Taanit 26-28; Megilah

29-30) According to the Talmud, half of the shift lived in

Jerusalem; the other half lived in Jericho, and supplied food

for their brethren in Jerusalem. (Taanit 27a)

Over time, certain shifts of kohanim lost their right to serve,

due to impropriety. One example is the shift of Bilgah; the

Talmud (Succah 56b) explains that they lost their right to

serve when a member of the family left Judaism, married a

Greek aristocrat, and blasphemed publicly in the Beit

haMikdash during the Greek invasion.

One of the only records of the names and cities of the shifts

of kohanim appears in the kinah of Eichah yashvah.

torczyner@torontotorah.com

Visit us at www.torontotorah.com & www.facebook.com/torontotorah

Biography

Torah and Translation

Megilat Taanit

Celebrations of Iyar

Rabbi Yisroel Meir Rosenzweig

Rabbi Chananiah ben Chizkiyah, Megilat Taanit

Megilat Taanit (The Scroll of Fasts) is a

short text with a stated goal of

delineating the days during which

fasting is forbidden, during several of

which eulogies are also forbidden.

Compiled at the end of the Second

Temple period, Megilat Taanit cites 35

days, organized according to the

calendar year, commemorating events

that took place over 500 years of Jewish

history - from the times of Ezra and

Nechemiah (5th century BCE) to the

rescinding of the Roman edict placing

idols in the Temple in 41 CE.

Translated by Rabbi Yisroel Meir Rosenzweig

The Talmud (Shabbat 13b) attributes

authorship of Megilat Taanit to Rabbi

Chananiah ben Chizkiah and his peers.

Noting this attribution, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch

Chajes (Divrei Neviim Divrei Kabbalah

ch.6) writes that Megilat Taanit dates to

approximately 80-100 years before the

destruction of the Second Temple. He

states that one shouldnt be bothered by

the fact that Tannaim who lived after the

destruction are quoted; their presence

demonstrates that the Megilat Taanit we

presently have is a layered text. The

original format of Megilat Taanit was

very brief, merely stating the calendar

date, event that took place, and what is

forbidden as a result of the festive nature

of the day. [These segments are bolded in

our accompanying translation]. Later

generations appended a commentary

expanding the details of these events.

The Talmud (Rosh HaShanah 19b, 18b)

records a dispute as to whether or not

the halachic significance of Megilat

Taanit has been voided, with the

celebrations included no longer observed

as a consequence of the destruction of

the Temple. The Talmud concludes that

it has been voided, with the exception of

Chanukah and Purim. The implications

of this conclusion are debated amongst

later authorities; the Pri Chadash (OC

496 Kuntres HaMinhagim 14) concludes

that it is subsequently forbidden under

all circumstances to add holidays to the

calendar year, while the Chatam Sofer

(OC 1:191) argues against the Pri

Chadashs proofs, noting that only

celebrations directly related to the

Temple are prohibited. One practical

implication of this question is Yom

HaAtzmaut, as the approach of the

Chatam Sofer may provide precedent for

establishing a Yom Tov to commemorate

a miracle in post-Talmudic times.

.

,

.

,

,

.

, ,

,

.

.

,

.

On the 7th of Iyar, the dedication of

the walls of Jerusalem, eulogies

should not be given. Since the nations

came and fought unsuccessfully against

Jerusalem, destroying its walls in the

process, the start of rebuilding was

declared a holiday. The dedication of

the walls of Jerusalem, eulogies should

not be given is mentioned twice in this

text. Once was when the Jewish people

came up out of exile, and again when

the Greeks breached the walls and the

Hasmoneans repaired them, as the text

states, And the wall was completed on

the 25th of Elul (Nechemiah 6:15). Even

though the wall was erected, the gates

had yet to be put in place, for it states,

Also at this time, I had not put doors in

the gates (ibid. 6:1). It says further,

[he] roofed it, erected its doors, its

locks (ibid. 3:15). As well as, and the

gatekeepers, singers, and Leviim were

appointed (ibid. 7:1). When their

appointment was completed, they made

the day into a holiday.

...

On the 14th is Minor Pesach [Pesach

Sheni], eulogies should not be given

and there should not be a fast

.

. ,

,

,

.

.

.

.

On the 23rd, the siege forces left

Jerusalem. As is written, And David

conquered the stronghold of Zion, which

is the city of David. (Samuel II 5:7) This

is the place of the Karaites now. For they

were oppressing the inhabitants of

Jerusalem; Jews werent able to come

and go during the day, only at night. On

the day they left, they made it a holiday.

On the 27th, the crowns were removed

from Jerusalem, eulogies should not

be given. In the days of the Greek

monarchy, they made crowns of roses

and hung them on the entrances of their

idolatrous

temples,

stores

and

courtyards. They serenaded their idols

with songs and wrote on the horns of

oxen and foreheads of mules that its

owner had no portion with the Supreme

G-d, as the Philistines before them did,

An ironsmith was not found...and the

filing of the blades of the plows and

plowshares. (Samuel I 13:19-21) When

the Hasmoneans came to power, they

removed them, and the day that they

removed them was declared a holiday.

yrosenzweig@torontotorah.com

Call our office at: 416-783-6960

This Week in Israeli History: 13 Iyar 5676 (May 16 1916)

The Sykes-Picot Agreement

13 Iyar is Shabbat

The Sykes-Picot Agreement, officially called the 1916 Asia

Minor Agreement, was a secretly negotiated arrangement

between the British and French governments regarding the

partition of the Ottoman Empire, should they succeed in

defeating the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

Sykes-Picot refers to the primary representatives of each

government in the final agreement: Franois-Georges Picot,

a professional diplomat with the French government and Sir

Mark Sykes, a British expert on the East. The Russian

Empire also played a small part in the discussion.

According to the agreement, France would control most of

Syria, Lebanon and the Galilee, with an Arab state in Syria.

Britain would control from Haifa into Mesopotamia (modern

Iraq) and create an Arab state between Gaza and the Dead

Sea, in the Negev. Finally, Jerusalem and surrounding areas

would be under international administration.

Rabbi David Ely Grundland

Meanwhile, British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey was a

supporter of Zionist aspirations to re-establish a Jewish state,

in part because of its important geopolitical positioning for the

British Empire. Furthermore, David Lloyd George, Chancellor

of the Exchequer and Local Government Board President

Herbert Samuels both spoke of the desirability of a Jewish

state in Palestine, and discussed their thoughts with Grey.

On May 16th, 1916, the Sykes-Picot agreement was signed by

the French Ambassador in London, Paul Cambon, and by Sir

Edward Grey. The Agreement was criticized for not properly

addressing Zionist aspirations, and for not taking into account

other discussions with Arab leaders.

The Agreement was repealed in 1920, at the San Remo

conference, which assigned the League of Nations Mandate for

Palestine to Britain.

dgrundland@torontotorah.com

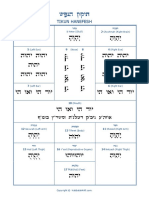

Weekly Highlights: May 21 May 27 / 13 Iyar - 19 Iyar

Time

Speaker

Topic

Location

Special Notes

R Jonathan Ziring

Parshah

BAYT

No-Frills Minyan

After hashkamah

R Yisroel M. Rosenzweig

Midrash Rabbah

Clanton Park

6:00 PM

R David Ely Grundland

Parent-Child Learning: Avot

Shaarei Shomayim

R Jonathan Ziring

Daf Yomi

BAYT

Rabbis Classroom

R Mordechai Torczyner

Gemara Avodah Zarah

BAYT

Simcha Suite

Hebrew

May 20-21

8:50 AM

Before Pirkei Avot

After minchah

Sun. May 22

Pesach Sheni

8:45 AM

R Jonathan Ziring

Responsa

BAYT

8:45 AM

R Josh Gutenberg

Contemporary Halachah

BAYT

9:15 AM

R Shalom Krell

The Book of Shemuel

Associated (North)

Hebrew

Mrs. Ora Ziring

Womens Beit Midrash

Ulpanat Orot

Not this week

R David Ely Grundland

Daf Yomi Highlights

R Mordechai Torczyner

Medical Halachah

Shaarei Shomayim

Beit Midrash Night

9:30 AM

R Mordechai Torczyner

Chabura: Two Ovens?

Yeshivat Or Chaim

University Chaverim

1:30 PM

R Mordechai Torczyner

Iyov: Behemoth / Leviathan

Shaarei Shomayim

Mon. May 23

9:30 AM

7:30 PM

Tue. May 24

Wed. May 25

Ethics from the Bookshelf:

Zeifmans LLP

Lunch served; RSVP to

rk@zeifmans.ca

The Merchant of Venice 201 Bridgeland Ave

12:30 PM

R Jonathan Ziring

12:30 PM

R Mordechai Torczyner

Tax Avoidance and

The Panama Papers

2:30 PM

R Jonathan Ziring

Narratives of the Exodus

8:00 PM

R Yisroel M. Rosenzweig

Archaeology in Halachah

Shaarei Tefillah

R Mordechai Torczyner

Shoftim: The Lefty

49 Michael Ct.

For women

R Jonathan Ziring

Eruvin

Yeshivat Or Chaim

Advanced

Thu. May 26

1:30 PM

Lunch served; RSVP to

SLF

2300 Yonge St. #1500 Jonathan.hames@slf.ca

Location: Contact

carollesser@rogers.com

For women

Lag baOmer

Fri. May 27

10:30 AM

Вам также может понравиться

- The Torah Revolution: Fourteen Truths that Changed the WorldОт EverandThe Torah Revolution: Fourteen Truths that Changed the WorldРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- To Contemplate The Holy: 25 Adar I, 5776/march 5, 2016 Parshat Vayakhel/Shekalim Vol. 7 Num. 26Документ4 страницыTo Contemplate The Holy: 25 Adar I, 5776/march 5, 2016 Parshat Vayakhel/Shekalim Vol. 7 Num. 26outdash2Оценок пока нет

- To Contemplate The Holy: 25 Adar I, 5776/march 5, 2016 Parshat Vayakhel Vol. 7 Num. 26Документ4 страницыTo Contemplate The Holy: 25 Adar I, 5776/march 5, 2016 Parshat Vayakhel Vol. 7 Num. 26outdash2Оценок пока нет

- In Search of A Non-Liberal Humanism: 3 Tammuz, 5775/june 20, 2015 Parshat Korach Vol. 6 Num. 37Документ4 страницыIn Search of A Non-Liberal Humanism: 3 Tammuz, 5775/june 20, 2015 Parshat Korach Vol. 6 Num. 37outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- As He FinishedДокумент4 страницыAs He Finishedoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- (WAM) Jewish Teaching About The MessiahДокумент3 страницы(WAM) Jewish Teaching About The MessiahOlimpia BuligaОценок пока нет

- The Goal of It AllДокумент4 страницыThe Goal of It Alloutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Yutorah Print: Acharei Mot 5774Документ8 страницYutorah Print: Acharei Mot 5774outdash2Оценок пока нет

- He Saw No OneДокумент4 страницыHe Saw No Oneoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Prophecy: The End of Reason?Документ4 страницыProphecy: The End of Reason?outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Rabbinic Authority Versus The Historical PDFДокумент35 страницRabbinic Authority Versus The Historical PDFRichard RadavichОценок пока нет

- 889Документ40 страниц889B. MerkurОценок пока нет

- Turning To The DeadДокумент4 страницыTurning To The Deadoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Shemot: What's in A Name?: 21 Tevet, 5776/january 2, 2016 Parshat Shemot Vol. 7 Num. 17Документ4 страницыShemot: What's in A Name?: 21 Tevet, 5776/january 2, 2016 Parshat Shemot Vol. 7 Num. 17outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Details Count: Parashat Naso Sivan 12 5774 May 30, 2015 Vol. 24 No. 32Документ4 страницыDetails Count: Parashat Naso Sivan 12 5774 May 30, 2015 Vol. 24 No. 32outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Teaching The Mesorah: Avodah Namely, He Is Both A Posek (Halachic Decisor) and An Educator For The EntireДокумент5 страницTeaching The Mesorah: Avodah Namely, He Is Both A Posek (Halachic Decisor) and An Educator For The Entireoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Society On The Move: 12 Sivan, 5776/june 18, 2016 Parshat Naso Vol. 7 Num. 38Документ4 страницыSociety On The Move: 12 Sivan, 5776/june 18, 2016 Parshat Naso Vol. 7 Num. 38outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Introduction To Theology Final ExamДокумент3 страницыIntroduction To Theology Final Examюрий локтионовОценок пока нет

- Purifying The Past and Proceeding To The Promised LandДокумент4 страницыPurifying The Past and Proceeding To The Promised Landoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Jewish Bible Commentary: A Brief Introduction To Talmud and MidrashДокумент24 страницыJewish Bible Commentary: A Brief Introduction To Talmud and MidrashmichaelgillhamОценок пока нет

- From Remembering To Re-Living and BackДокумент4 страницыFrom Remembering To Re-Living and Backoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- House House: From ToДокумент4 страницыHouse House: From Tooutdash2Оценок пока нет

- House House: From ToДокумент4 страницыHouse House: From Tooutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Emor 4:7:23Документ7 страницEmor 4:7:23Kenneth LickerОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент68 страницUntitledoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент2 страницыUntitledoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- The Drama of Tashlich: This Issue of Toronto Torah Is Sponsored by Nathan Kirsh in Loving Memory of His Parents andДокумент4 страницыThe Drama of Tashlich: This Issue of Toronto Torah Is Sponsored by Nathan Kirsh in Loving Memory of His Parents andoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Repentance As FreedomДокумент4 страницыRepentance As Freedomoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- 35 SE NassoДокумент8 страниц35 SE NassoAdrian CarpioОценок пока нет

- A Deidade de YeshuaДокумент8 страницA Deidade de YeshuaEDUARDO BRANDÃOОценок пока нет

- golah, exile and Diaspora, and move to a state of הלואג geulah, redemption, then we must recognize that the phonetic difference between these twoДокумент1 страницаgolah, exile and Diaspora, and move to a state of הלואג geulah, redemption, then we must recognize that the phonetic difference between these twooutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Jesus Is Not The MessiahДокумент28 страницJesus Is Not The MessiahRoberto FortuОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент4 страницыUntitledoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Guidelines For Theological DiscussionДокумент7 страницGuidelines For Theological DiscussionmjtimediaОценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Call Me by My Rightful Name: 24 Tammuz, 5775/july 11, 2015 Parshat Pinchas Vol. 6 Num. 40Документ4 страницыCall Me by My Rightful Name: 24 Tammuz, 5775/july 11, 2015 Parshat Pinchas Vol. 6 Num. 40outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Lesson 1 On GenesisДокумент8 страницLesson 1 On GenesisJULIUS CESAR M. EREGILОценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- 2010 Mitternacht TalmudandMidrashДокумент24 страницы2010 Mitternacht TalmudandMidrashpelis 22Оценок пока нет

- The Sons and Daughters of Anath: Primal Religious Influences On Jephthah's Vow and His Daughter's Response in Judges 11:29-40Документ26 страницThe Sons and Daughters of Anath: Primal Religious Influences On Jephthah's Vow and His Daughter's Response in Judges 11:29-40Matt LumpkinОценок пока нет

- Jesus Is Not The MessiahДокумент28 страницJesus Is Not The MessiahRoberto FortuОценок пока нет

- The Work-Life BalanceДокумент4 страницыThe Work-Life Balanceoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 4-A Brief History of Hermeneutics-CompletedДокумент35 страницChapter 4-A Brief History of Hermeneutics-CompletedArockiaraj RajuОценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Concepts of Messiah: A Study of the Messianic Concepts of Islam, Judaism, Messianic Judaism and ChristianityОт EverandConcepts of Messiah: A Study of the Messianic Concepts of Islam, Judaism, Messianic Judaism and ChristianityРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Center For Advanced Judaic Studies, University of PennsylvaniaДокумент13 страницCenter For Advanced Judaic Studies, University of PennsylvaniaShlomoОценок пока нет

- CoreДокумент25 страницCoreSteffanie OlivarОценок пока нет

- Zugoth - "Pairs"Документ10 страницZugoth - "Pairs"Anonymous wKjrBAYRoОценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Toronto TorahДокумент4 страницыToronto Torahoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Jewish SexualityДокумент81 страницаJewish SexualityDavid Saportas LièvanoОценок пока нет

- Parashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777Документ4 страницыParashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777outdash2Оценок пока нет

- The Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny JoelДокумент2 страницыThe Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny Joeloutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתДокумент28 страницChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- 879645Документ4 страницы879645outdash2Оценок пока нет

- The Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)Документ4 страницыThe Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)outdash2Оценок пока нет

- The Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli BelizonДокумент3 страницыThe Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli Belizonoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- 879547Документ2 страницы879547outdash2Оценок пока нет

- 879510Документ14 страниц879510outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Flowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra SchwartzДокумент2 страницыFlowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra Schwartzoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Consent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. SchacterДокумент3 страницыConsent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacteroutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lДокумент2 страницыShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Performance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel ZylbermanДокумент6 страницPerformance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel Zylbermanoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Reflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of BrachosДокумент3 страницыReflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of Brachosoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lДокумент2 страницыShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Experiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem PennerДокумент3 страницыExperiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem Penneroutdash2Оценок пока нет

- The Power of Obligation: Joshua BlauДокумент3 страницыThe Power of Obligation: Joshua Blauoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- I Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah NagarpowersДокумент2 страницыI Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah Nagarpowersoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Lessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi RommДокумент5 страницLessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi Rommoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- What Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery JoelДокумент3 страницыWhat Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery Joeloutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Lessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus ProcessДокумент3 страницыLessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus Processoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- A Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua FassДокумент3 страницыA Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua Fassoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Chag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. JoelДокумент2 страницыChag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Torah To-Go: President Richard M. JoelДокумент52 страницыTorah To-Go: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Yom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel DavisДокумент1 страницаYom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davisoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- 879399Документ8 страниц879399outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Kabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther JoelДокумент2 страницыKabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther Joeloutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Nasso: To Receive Via Email VisitДокумент1 страницаNasso: To Receive Via Email Visitoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Why Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of IsraelДокумент5 страницWhy Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of Israeloutdash2Оценок пока нет

- 879400Документ2 страницы879400outdash2Оценок пока нет

- José Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37Документ16 страницJosé Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37outdash2Оценок пока нет

- Two of Repentance: Rabbi Moshe Chaim SosevskyДокумент4 страницыTwo of Repentance: Rabbi Moshe Chaim Sosevskyoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Introduction To World Beliefs and Religion: Festivals in JudaismДокумент25 страницIntroduction To World Beliefs and Religion: Festivals in JudaismCeline JewelОценок пока нет

- Beis Moshiach #621Документ37 страницBeis Moshiach #621Boruch Brandon MerkurОценок пока нет

- Zohar - Idra Zuta Qadusha - Lesser AssemblyДокумент10 страницZohar - Idra Zuta Qadusha - Lesser AssemblyVictoria Generao100% (1)

- Animal Experimentation: Rabbi Alfred CohenДокумент14 страницAnimal Experimentation: Rabbi Alfred Cohenoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Tikun HaNefesh PDFДокумент1 страницаTikun HaNefesh PDFJoão Carlos Marini100% (1)

- Kabbalah Jewish Mysticism IДокумент21 страницаKabbalah Jewish Mysticism IMagicien1Оценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент10 страницUntitledoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Megillah 21Документ79 страницMegillah 21Julian Ungar-SargonОценок пока нет

- Beitzah 36Документ58 страницBeitzah 36Julian Ungar-SargonОценок пока нет

- Bless HaShem 100 Times A DayДокумент13 страницBless HaShem 100 Times A DayJacquelineGuerreroОценок пока нет

- Beis Moshiach #825Документ39 страницBeis Moshiach #825B. MerkurОценок пока нет

- JudismДокумент42 страницыJudismpasebanjatiОценок пока нет

- Shabbat Shalom From Cyberspace: Ki TesseДокумент10 страницShabbat Shalom From Cyberspace: Ki TessesambousacОценок пока нет

- Perek XIX Daf 134 Amud A: NotesДокумент6 страницPerek XIX Daf 134 Amud A: NotesFelipe DamíanОценок пока нет

- Mizbeach (Altar)Документ4 страницыMizbeach (Altar)Rabbi Benyomin HoffmanОценок пока нет

- Thanksgiving Seder For Families With Small ChildrenДокумент5 страницThanksgiving Seder For Families With Small Childrenimabima100% (2)

- Rav Soloveitchik-The Common-Sense Rebellion Against Torah AuthorityДокумент6 страницRav Soloveitchik-The Common-Sense Rebellion Against Torah AuthorityTechRav100% (7)

- Kabbalah Study GuideДокумент87 страницKabbalah Study GuideEdward Andres Loaiza Pedroza100% (1)

- Mutual Respect: by Ariel Sacknovitz, Director of Production, 12th GradeДокумент8 страницMutual Respect: by Ariel Sacknovitz, Director of Production, 12th Gradeoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Stay Updated On Facebook @kessermaariv: On Parsha and The Chain of MiraclesДокумент5 страницStay Updated On Facebook @kessermaariv: On Parsha and The Chain of MiraclesshasdafОценок пока нет

- Artificial Feeding On Yom Kippur: Rabbi) - David BleichДокумент14 страницArtificial Feeding On Yom Kippur: Rabbi) - David Bleichoutdash2100% (1)

- Tzitzis - Parsha MathДокумент2 страницыTzitzis - Parsha MathRabbi Benyomin HoffmanОценок пока нет

- The International Weekly Heralding The Coming of Moshiach: Long Live The Rebbe Melech Ha'Moshiach Forever and Ever!Документ34 страницыThe International Weekly Heralding The Coming of Moshiach: Long Live The Rebbe Melech Ha'Moshiach Forever and Ever!B. MerkurОценок пока нет

- Garden of Peace Chapter 1 PDFДокумент3 страницыGarden of Peace Chapter 1 PDFDaville Bulmer100% (1)

- OU Passover Guide 5777Документ108 страницOU Passover Guide 5777GabrielaОценок пока нет

- Megillah 13Документ68 страницMegillah 13Julian Ungar-SargonОценок пока нет

- Moral Clarity Found in Our Hagaddah: Professor Nechama PriceДокумент4 страницыMoral Clarity Found in Our Hagaddah: Professor Nechama Priceoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- A Lesson in Life, On A LifeboatДокумент4 страницыA Lesson in Life, On A Lifeboatoutdash2Оценок пока нет

- Not Just Another Winter Festival: Rabbi Reuven BrandДокумент4 страницыNot Just Another Winter Festival: Rabbi Reuven Brandoutdash2Оценок пока нет