Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Bergesen. 1977. Political Witch Hunts (Rituals)

Загружено:

Mihai Stelian RusuАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Bergesen. 1977. Political Witch Hunts (Rituals)

Загружено:

Mihai Stelian RusuАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Political Witch Hunts: The Sacred and the Subversive in Cross-National Perspective

Author(s): Albert James Bergesen

Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Apr., 1977), pp. 220-233

Published by: American Sociological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2094602

Accessed: 03-01-2016 06:35 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Inc. and American Sociological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to American Sociological Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

POLITICAL WITCH HUNTS:

THE SACRED AND THE SUBVERSIVE IN

CROSS-NATIONAL PERSPECTIVE*

ALBERT JAMES BERGESEN

University of A rizona

American Sociological Review 1977, Vol. 42 (April):220-233

This paper proposes a general theory of political witch hunts, viewing them as ritual mechanisms for the periodic rejuvenation of collective sentiments in national societies. Ultimate

national purposes require not only their worshipers, but also their enemies. When these sacred

forces penetrate daily reality, then their opposites-subversives-will also appear in daily institutional life. The corporateness of societies, as expressed in their political system, is theoretically

linked to the penetration of transcendent reality into daily life, and a witch-hunting dispersion

index is proposed to measure the extent to which subversion is ritually discovered throughout a

society's social institutions. The overall rate of witch hunting is also measured. Data on rates

of political it-itch hunting between 1950 and 1970 for 39 countries is presented to evaluate

the general theoretical argument. The data suggest that as societies politically express more

of their corporate national interest they ritually cleanse more institutional areas, as measured by the dispersion index. A long wit/ the representation of the corporate national interest, the overall rate of witch hunting is significantly affected by country size, lev el of economic development and the relative power of the state. The dispersion of uw'itchhunting, on

the other hand, is unaffected by these control variables and seems to be a more purely

Durkheimian phenomenon.

Modem national societies, like primitive societies, must periodicallyrenew the

meaning of corporate existence. Where

rites were once performedto symbolizations of the tribe, they are now performed

to symbolizations of the nation-state.

Durkheim (1965) observed that sacredness required profanity, and sacred national purposes seem to requirethose who

would undermineand subvertthem. Similarly, as Durkheimargued that crime is a

normalaspect of social life, so are political witch hunts. The nation-state'screation of political subversives, no less than

the community's manufacture of deviance, is a mechanism for renewing

common moral sentiments and redefining

the contours of social reality.

lIhistheoreticalperspective on political

witch huntingderivesfrom and links Durk* This is a revised version of a paper read at the

American Sociological Association meetings,

Montreal, 1974. Janine Blair assisted with the computerwork andcommentsfrom MorrisZelditch,Jr.,

John W. Meyer and Ronald Schoenberghave been

most helpful. I especially want to thank Beverly

Duncan and Otis Dudley Duncan for their suggestions and assistance on an earlierdraftof this paper.

heim's observations on religious ritual

and myth and the social functions of

crime. His work in religionand crime has

a common concern with the function of

ritual activity in creating and maintaining

collective reality, whether symbolic representations in the analysis of primitive

religion or moral boundariesin the analysis of crime. However, there has been little intellectual contact between later students of the sociology of religion (for

example, Swanson, 1964; 1967; Douglas,

1966; 1970;Goffman, 1956;Berger, 1969;

Luckmann, 1967)and the sociology of deviance (Erikson, 1966). Moveover, this

theoretical formulationis congruous with

two empirical findings which recur in

studies of political trials (Cohen, 1971;

Kirchheimer, 1961), purges (Brzezinski,

1956; Conquest, 1968; Dallin and Breslauer, 1970), rectification campaigns

(MacFarquhar, 1960; Goldman, 1965;

Solomon, 1971; Baum and Teiwes, 1968)

and loyalty controversies (Bell, 1964;Lipset, 1955; Parsons, 1955). Efforts at exposing, unmasking and discovering subversives seem oriented as much toward

dramatizingtheir presence as toward ac-

220

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

POLITICAL WITCH HUNTS

tually apprehendingthem; and, accordingly, the arrests, trials, confessions and

other acts which comprisea modernpolitical witch hunt seem largely ritualisticin

character.

The ritual mobilizationof a community

searching for imaginary enemies traditionally has been viewed as largely

epiphenomenal-the real causes of witch

huntingare thought to lie elsewhere. The

trials, purges and political terrorof Communist regimes, for instance, have been

seen as an outcome of the fear and

paranoia generated by totalitarianstates

and as an "instrumentof the state" used

by elites to thwart potential opposition

and maintainpolitical power (Brzezinski,

1956). Similarly, the hysteria of the

McCarthy period has been dismissed as

the paranoidprojections of social groups

experiencing status stress (Bell, 1964). In

contrast, I want to propose a theory of

political witch hunts explicitly based on

their distinctly mythical and ritualistic

character.

221

Durkheim (1965) called positive rites

where the Nation and the People are worshipped: coronations, inaugurations,nationalholidays and memorialdays. Others

are negative rites, like witch hunts.

Throughsuch activities as the purge, trial,

investigation, accusation, arrest and imprisonment, society creates its own internal enemies to ritually reaffirmthe very

sacred national purposes which subversives are supposedly undermining. The

corporate nation needs not only its worshipers, but also its enemies. This process

of moralrevitalizationis complex, centering on the interrelationshipof corporate

society, its collective representationsand

the ritualwhich rejuvenatesand redefines

them.

The Penetration of Ordinary Life by

Sacred Forces

Social realityis a matterof definition.It

is neither naturally mundane, with ordinary people and propanemotives, nor sacred, with transcendentpolitical purposes

individuals and social events.

animating

THEORY

Depending upon how closely a nation's

collective myths are mergedwith the proThe Sacred and the Subversive

fane and ordinary,more or less ultimate

For Durkheim,the moral reaffirmation political significance can be infused into

of collective life involved two causally in- daily existence. The penetration of daily

terrelatednotions-one, that society pre- life by sacred forces is, in effect, a varisents itself througha varietyof symboliza- able, and not the singular property of

tions or collective representationsranging primitive religious systems as we have

from materialobjects to systems of ideas; traditionallybelieved.'

the other, that society mobilizes itself

In pluralisticWestern societies, by and

throughrites performedto these symbolizations as a means of periodicallyrenewI Bellah (1970:27), writing on religious evolution,

ing their presence and simultaneouslyre- argues

that one of the distinguishing characteristics

newing the larger social order they sym- of primitive religion is "the very high degree to

bolically represent. Like primitive which the mythical world is related to the detailed

societies, modem national societies pre- features of the actual world. Not only is every clan

and local group defined in terms of the ancestral

sent themselves through numerous sym- progenitors

and the mythical events of settlement,

bolizations. Some are materialobjects like but virtually every mountain, rock, and tree is exflags, emblems and political leaders. plained in terms of the actions of mythical beings."

Others are symbolic representations of The same could be said for the so-called modern

the nationalcollectivity itself - images of religious situation. In certain highly ideological

societies, for example, virtually every individual acthe Nation of the People as organic en- tion

is linked to the transcendent world of History or

or

such

as

tities,

political ideologies

Nature and every event is seen as an instance of the

Communism, Socialism, Fascism or De- mythical forces of "imperialism," "socialism" or

mocracy. As in primitive societies, rites "capitalism." Because our religious representations

are at the same time the theory of our own universe,

are performedto these modern collective we

have had a very difficult time assigning some

representationsof the corporate national beliefs to the category "myths" and others to what

community. Some of these rites are what we take as constituting our "real" reality.

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

222

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

large, life is understoodas the interaction

of groups and personages governed by

secular and profane motivations of the

here and now. Life is not filled with the

rumblingand movement of Marx's historically preordainedstrugglebetween social

forces in "constant opposition to one

another, carrying on an uninterrupted,

now hidden, now open fight." Conversely, the two most pronounced examples of sacred political forces mingling

with people in daily life are Fascist and

Communistsocieties where there is a very

close connection between religious representations and daily existence.

daily activity becomes the realization of

these transcendent realities. The ritualistic creation of enemies, as a means of

renewing the presence of these sacred

forces, centers on discovering "enemies

of the people," the nation, and even

enemies of Nature and History itself.

Terror... its chief aim is to make it possible

for the force of nature or of history to race

freely through man . . . [it] singles out the

foes of mankindagainst whom terror is let

loose, and no free action of eitheropposition

or sympathy can be permitted to interfere

with the elimination of the "objective

enemy" of History or Nature, of the class or

the race. Guiltand innocence become senseless notions; "guilty" is he who standsin the

Underlyingthe Nazis' belief in race laws as

way of the natural or historical process

the expressionof the law of naturein man, is

which has passed judgement over "inferior

Darwin's idea of man as the product of a

races," over individuals "unfit to live,"

naturaldevelopment which does not necesover "dying classes and decadent peoples."

sarilystop with the presentspecies of human

Terror executes these judgements, and bebeings, just as under the Bolsheviks' belief

fore its court, all concerned are subjectively

in class-struggleas the expression of the law

of historylies Marx'snotionof society as the

innocent: the murdered because they did

product of a gigantic historical movement

nothing againstthe system, and the murderwhich races accordingto its own law of moers because they do not really murder but

tion to the end of historicaltime when it will

execute a death sentence pronounced by

abolish itself. (Arendt, 1973:463)

some higher tribunal.The rulers themselves

do not claim to be just or wise, but only to

These ideologies can be consideredDurkexecute historical or natural laws; they do

heimian representationsof the corporate

not apply laws, but execute a movement in

social order. Individualscome and go but

accordancewith its inherent law. Terror is

groups persist: the idea of an unending

lawfulness, if law is the law of the moveuniverse of evolving Nature or History is

ment of some suprahumanforce, Nature or

the perfect symbolization for the corpoHistory. (Arendt, 1973:465)

rate continuity of society over the temporary lives of mundane individuals. From

the point of view of highly corporate

societies, those countries in which groups

and classes do not realize their participation in the transcendentreality of historical development are said to have "false

consciousness." From the other side,

these corporate societies are described as

highly "ideological" and their people as

"brainwashed." Each side claims its experience of reality to be correct and the

other's false. What is experienced,

though, is mediatedby each society's definition of reality, and there is no absolute

reality independent of society and its imposed system of classificationsand definitions.

Political ideologies, like the sacred

forces of History and Nature, or the ideas

of the People or the Nation can penetrate

and merge with ordinary reality so that

Ritual Transformations: Trial, Purge,

Accusation, Investigation

There is no clear line separating ordinary mundane reality and the larger purposes and personages of a transcendent

reality such as History or Nature. One can

see himself, his work and others as the

embodiment of the laws of history working themselves out here on earth, as when

factory work is experienced as building

socialism and realizing the historical role

of the proletariat. One can also find oneself engaged in mortal combat with these

cosmic forces and being charged with

being an enemy of socialism and conspiring against the laws of social development. In the first situation, one is marching with the sacred forces that have penetrated one's existence and, in the other,

one is marching against them. In both

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

POLITICAL WITCH HUNTS

situations, one will probably be doing

identical activities-only the definitions

will have changed.

Political witch hunts are the ritual

mechanisms that transform individuals,

groups, organizationsor culturalartifacts

from things of this world into actors

within a mythical universe. These rituals

are the social "hooks" that keep sacred

transcendentforces present in the lives of

ordinarypeople and relevantfor everyday

institutional transactions. In effect,

Berger's (1969) "Sacred Canopy" extends to different lengths, more or less

penetrating everyday reality, with ritual

being the "lock" which keeps sacred reality tied to daily reality. The discovery of

"wreckers" in factories, "hostile elements" in the Party bureaucracy,

"bourgeois thoughts" in literature, and

"anti-state" activity in governmentis the

ritual activity which functions to reaffirm

the presence of the sacred struggle between Capitalismand Socialismwithinthe

fabric of everyday life.

The crimes one is chargedwith and the

motives imputed are not of this world.

Through some ritual transformational

logic, they become part of the mythical

reality of political ideology where, for

example, "proletarianvirtue" is battling

"bourgeois selfishness" and the

"socialist and capitalist lines" are struggling for supremacy.Trivialactivityis ritually transformedinto actions of large historical forces. Using one kind of fertilizer

or another on a communalfarm is transformed into the mythicalworld of "taking

the capitalist road" or "following the

socialist road." Readinga book or seeing

a play is transformed into being

"poisoned by bourgeois thoughts" or

being a "communist sympathizer." Correspondence with friends abroad can be

"restoring

transformed into acts

capitalism," making one an "imperialist

agent" and "counterrevolutionary."

When these ritual convulsions occur,

ordinary reality loses its usual meaning

and human beings mingle with mythical

beings, playing roles in a cosmic drama,

As HannahArendtobserved, questions of

guilt and innocence are irrelevant; they

are causal relationsrooted in the structure

of meaning of mundanereality and make

223

no sense when the cletinition of reality has

been ritually shifted to the mythical world

of political ideology. What one "really"

did or did not do is irrelevant, for the

"doing" has meaning in a world that has

been supplanted by a mythical universe

with its own characters, motives and

crimes. Being an "ultra-leftist," "ultrarightist," or "left in appearance but right

in essence" makes no sense within the

meaning structures of this world; they are

acts, motives and types of people from the

world of political ideology.

One does not enter this mythical world

through any act one performs. The sacred

and profane are two different worlds,

there is nothing one can do in one world

to enter into the other. Hence, guilt

and innocence have never mattered during political witch hunts. The most trivial

infraction, or no action at all, has the same

weight as the most serious crime. It is the

activity of the trial, the purge, the accusation or the self-confession which transforms individuals from one reality to the

other.

It is no wonder then that witch hunts

appear irrational, terrifying and unreal. In

some sense, they are truly unreal and irrational, for their logic derives from the

symbolic significance of the ritual encounters between mythical beings and forces

and not from the actualities of human

conduct. There is no intrinsic quality to

that which is treated as sacred and there is

no intrinsic quality to individuals considered subversive and dangerous. Durkheim

wondered how such insignificant things as

lizards, frogs, turkeys, ants and caterpillars could, in and of themselves, engender

the sense of the sacred; and we have also

wondered how the wording of a Girl Scout

Handbook, a play exploring the thoughts

of a conscientious objector, or interest in

the United Nations, race relations and

civil liberties could be considered dangerous, subversive and un-American. Anything can serve as a vehicle for the designation "sacred" or "subversive," and

anyone can become "an enemy of the

people" and "think dangerous thoughts."

As Arendt (1973:462) observed:

Totalitarianlawfulness,defying legality and

pretending to establish the direct reign of

justice on earth, executes the law of History

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

224

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

or of Nature without translating it into

standardsof right and wrong for individual

behavior. It applies the law,directly to mankind without botheringwith the behavior of

men.

are they embodied in specific political institutions to the extent to which the

CommunistParty is considered the literal

embodimentof the "proletarianwill." Finally, the American People or Public

Opiniondo not have a mythicallink to the

specifics of historical evolution as does

Societal Differences in Witch-Hunting

the

Communist's Proletariat. The ManActivity

ifesto stated, "The history of all hitherto

Collective representations mirror the society is the history of class struggles.

social order, and Durkheim'sobservation Freemanand slave, patricianand plebian,

that the attitude of respect toward our lord and serf, guildmaster and jourgods is similar to the attitude of respect neyman . . ." and now, in our times, the

toward social authorityprovides the now bourgeoise and proletariat. In compariwell-known (Swanson, 1964; 1967) theo- son, the "When in the course of human

retical linkage between corporate social events . . ." beginning to the Declaration

groups and religious experienceswith sa- of Independence is a much more casual

cred forces and spirits.

and almost offhand reference to the

As mentioned earlier, tMe extent to primordialorigins of the American nation

which transcendent reality merges with compared with the lockstep progression

daily reality appearsto be a variableand, of History in the Manifesto that has

as these sacred forces are symbolic repre- broughtforth present-day Socialist counsentations of the corporate social order, tries. There is also no single body of literavariationin the extent to which that cor- ture for the liberal democraticWest comporateness is expressed should be re- parable to that of Marxismdefining, say,

flected in variationsin the extent to which America's "Historical Role." There are

the sacred cosmos penetrates mundane no "sacred texts" and no common set of

reality.2 The more the corporate interest intellectual heroes like Marx, Lenin and

of the nation as a whole is politically ex- Mao. Marxism provides one version of

pressed, the more sacred forces should ultimatereality, which is modifiedto each

intervene in daily life, and the more particularsocial system, but is still linked

witch huntingthere should be to reaffirm to the transcendentprocess of social dethese collective representations and se- velopment and the laws of History.

cure their presence in daily affairs. In efExpressing corporateness: political

fect, as the corporateinterest of the soci- party systems. Swanson (1967; 1971) arety is weakened, so is the strengthof the gues that social collectivities have a corgods. They become less powerful, more porate existence; they can make collecelusive and more tenuously tied to the tive decisions and take collective action.

For national societies, the structural

specifics of daily life.

For example, representations of the mechanismthroughwhich collective decicorporatenessof the United States are not sions are formulatedand collective action

as well developed as those of Communist taken is the institution of government.

countries. The idea of the American Collectivities vary in the degree to which

People, or Public Opinion, as a force or they allow the expression of the corporate

spirit in our lives does not penetrate our interest of the collectivity as a whole, as

existence to the extent to which repre- opposed to the interests of the constituent

sentationslike "the thoughtsof Chairman groups within the society. Political party

Mao" do in China (Schwartz, 1968). Nor systems are the most common structural

mechanismfor expressinggroupinterests,

2 This theoretical discussion leans heavily on the

whether corporate or constituent.3

work of Swanson (1964; 1967) on corporate groups

and experiences with the sacred in daily life. His

ideas on immanence and constitutional systems are

the backbone of my thinking about these matters,

and those familiar with his work will see the strong

effect he has had on my thinking.

I The expression of corporate versus constituent

interests need not always be mutually exclusive, although it most often appears that way. One exception would be a country like France which has a

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

225

POLITICAL WITCH HUNTS

Multi-party systems, such as the European parliamentarystates, allow the most

penetrationof constituent group interests

into the structureof government. Specific

groups-agricultural, religious, working

class-each have their own party and,

with the proportionalrepresentationelectoral arrangements multi-party systems

usually have, these parties are virtually

guaranteed some seats in the legislature.

Two-partyarrangements,like the AngloAmerican countries, collapse many

specific group interests into two broadly

based parties. The emphasis is upon what

the different groups have in common,

rather than what separates them, and

more of the common corporateinterest of

the society is manifested. Finally, there

are one-partystates, whetherCommunist,

Fascist or one-party nationalist. Here,

only the interest of the collectivity as a

whole is represented by the single party.

Partialinterests are not provideda formal

role throughpartiesin the politicalorganization of these nations as corporate entities.

Some Hypotheses

The penetration of sacred forces into

ordinaryreality is not the sole propertyof

primitive belief systems, and the ritualistic search for enemies as a means of reaffirmingthese transcendentforces is not a

propertyof any one kind of society; both

vary accordingto the extent to which corporate, as opposed to constituent, group

interests are politically expressed. We

have been referring to daily affairs and

everyday reality in quite general terms.

We can refer to them more precisely in

terms of the differentinstitutionalspheres

of which daily reality is composed. We

can speak of the extent to which religious,

political, economic or educationalinstitutions are found infested and pollutedwith

subversion.

From the preceding theoretical discussion, the following hypotheses can be

multi-partysystem allowing for the expression of

constituent group interests and a strong and centralized national bureaucracywhich expresses the

corporateinterests.

made: (1) Other things being equal, there

should be a positive relationship between

the expression of corporate interests and

the distribution of witch hunting across a

society's social institutions, reflecting the

more extensive penetration of daily institutional reality by sacred forces. (2) We

should also expect the expression of society's corporate interest to be positively

related to increased frequency of witch

hunting in general. One-party states

should experience subversion in more institutional areas and have a higher overall

rate of witch hunting than two-party

states, and they, in turn, should experience subversion in more institutional

areas and have a higher overall rate than

multi-party states.

DATA AND

METHOD

Independent Variables

Countries were chosen for analysis if

they had a stable party system from 1950

through 1970. A stable system is defined

as one in which the party system did not

change and the country was not involved

in major political conflicts. The attempt

was to isolate, as much as possible, the

effect of party system upon a country's

propensity tor witch hunting. The countries are listed in Appendix 1. A country's

party system was coded from Blondel's

(1973) classification of national legislatures. Countries were coded one, two and

three, representing one-, two- and multiparty systems. The 39 countries differ in

population size, level of economic development and the degree to which political power is concentrated within the state,

as well as with respect to political party

system. The former factors may be seen

as rivals to party system in accounting for

cross-national differences in witch hunting

and, as I am arguing that other things

being equal, corporateness should be related to the dispersion and rate of witch

hunting, I have compiled measures of

each country's 1960 population (IBRD,

1973), 1960 per capita GNP (IBRD, 1973)

and per capita internal security forces

(Taylor and Hudson, 1971) to control for

these factors.

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

226

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Dependent Variables

Frequency of witch hunting. Counts of

witch huntingactivityare obtainedby coding government activities (for example,

trials, purges, arrests) from news sources

whenever these activities charge someone

with threateningor standingin opposition

to the nationalinterest. Since government

represents the social structure through

which the nation itself takes collective action, only acts by a country's national

government will be coded (this includes

the military). Charges of subversion by

private citizens, for instance, will not be

coded. The New

York Times Index,

1950-1970, was chosen as the basic

source because of its broad international

coverage.4 The scheme used for coding

provides for 19 different kinds of government acts, rangingfrom mere charges of

subversive activity to large-scale purge

trials. Each category is mutually exclusive. The specific code categories are: (1)

warnings of danger to the nation, (2)

specific charges, (3) discovery of plots, (4)

calls of public action to thwart subversion, (5) proposed actions, (6) new laws,

ordinances or executive decrees, (7) restrictions of personal activity, (8) expulsion of agents of foreign governments, (9)

deportations, (10) arrests, (11) imprisonment, (12) resignations, (13) purges, (14)

court actions, (15) mass mobilizations,

(16) censorship campaigns, (17) political

trials, (18) sentences following trials and

(19) government investigations. This

scheme is intended to cover the great

variety of government activity a society

can employ in creatingthe idea of subversion in its midst.

The coding was done by four graduate

students. Activities were assigned codes

independently by two coders and the

value of Robinson's (1957) coefficient of

4 There are numerous sources of bias involved in

using press reports. There are actions taken by political authorities in identifying and prosecuting subversives that never reach the pages of the Times.

This would seem particularly true of Communist

states and countries with little contact with the

United States. There is also undoubtedly a bias in

terms of the number of events reported for large and

prestigious nations over those smaller and less

known. For a discussion of some of the problems in

coding news sources, see Danzger (1976).

agreement was found to be .85. This compares favorably with the reliability

achieved by other researchers who have

coded news sources (see Gurr, 1968;

Feierabend and Feierabend, 1966; Banks,

1971).

The coding scheme also provides for 36

different institutional areas in which subversion might be discovered. The information available about the activities made

it impossible to determine the institutional

areas for 57 percent of the government

activities coded. For the present analysis,

these 36 areas are grouped into seven gen(1)

categories:

institutional

eral

government-national and local, (2) military personnel and facilities, (3) educational institutions and students, (4)

economy, (5) intellectuals, (6) religious

groups and institutions and (7) a category

for foreigners.

The coding procedure works as follows.

The Times Index is read for each country.

When one of the code activities (a trial,

purge, arrest) is encountered, it is coded

along with the institutional area where the

subversion was located. This procedure

generates the basic data on both the overall volume of witch hunting (the number of

government activities) and its institutional

location. Some countries could not be

coded for the full 21 years (such as the

African countries, which did not become

independent until around 1960), so each

country's total number of activities was

divided by the number of years coded,

creating a witch-hunting per year variable.

The Witch-Hunting Dispersion Index.

To measure the dispersion of witch-hunting activity throughout a society's institutional space, a population diversity index

is employed. This 'dispersion index,

adapted from Simpson's (1949) index of

population diversity, is defined as

Nj (Nj- 1)

D= 1 -E

N(N-1)

where Nj equals the number of witchhunting activities in the jth institutional

category, N equals the total number of

witch-hunting activities and D equals the

degree of dispersion of witch hunting

across institutional categories. The higher

the score on the index, the more dispersed

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

POLITICAL WITCH HUNTS

227

for country size (population), level of

economic development (GNP) and the

relative power of the state (internalsecurity forces) are entered into the following

regressionanalysis along with the variable

political party system. It was logged to

help correct for the skewed distributionof

the witch-huntingper year variable. The

correlationmatrixfor the regression analysis is presented in Appendices 2 and 3.

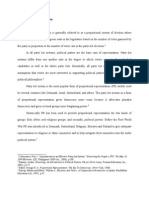

The regression analysis in Table 1

strongly supports our first hypothesis

that, other things being equal, there is a

positive relationship between party system and the dispersion of witch hunting

FINDINGS

throughouta society's institutionalspace.

The political party variable has a strong

The Dispersion of Subversion through Ineffect, with a beta of .575. It is also the

stitutional Space and the Overall Rate of

only

unstandardizedcoefficient twice its

Witch Hunting

standard error. The effect of population

We can measure the extent to which and GNP are negligiblewith betas of .047

different institutional areas are polluted and .042, respectively, and the indicator

with subversion using the dispersion of state power, internal security forces,

index mentioned earlier. The higher the has a small negative effect with a beta

score the more dispersion; the lower the of -.242.

score the more witch hunting is concenThe second hypothesis stated that,

trated within a few institutional areas. other things being equal, there is a posiAppendix 1 presents the total number of tive relationship between party system

witch-hunting activities by institutional and the overall rate of witch hunting.

area for each country. Control variables Politicalparty system was significantlyre-

the witch huntingacross institutions.This

index was computed across the

categories: government, military, education, economy, intellectuals, religion,

foreigners and agents of foreign governments. At least ten government activities

were arbitrarilychosen as a minimumto

compute an index score. No index was

computed for the following countries, as

they had less than ten acts within their

institutional areas: Chad, Guinea, Ivory

Coast, Senegal, Tanzania,Australia,New

Zealand, Colombia, Belgium, Iceland and

Ireland.

Table 1. Regression Coefficients of Witch-HuntingDisperson Index and Log Witch Hunting per Year

on Political Party System, Internal Security Forces, Population and per Capita Gross National Product

IndependentVariables

Political

Party

System

Dependent

Variables

Witch-Hunting

DispersionIndex

Log Witch-Hunting

Activities per Year

46.162

(22.917)

.698*

(.307)

Internal

Security

Forces

Population

Per

Capita

GNP

UnstandardizedCoefficientsa

-.762

.0027

.00473

(.688)

(.0118)

(.0298)

.193*

.000538*

.0009*

(.0088)

(.000174)

(.00041)

Constant

R2

774.20

(69.89)

2.675

(.950)

.271

.446

StandardizedCoefficients

Witch-Hunting

Dispersion Index

Log Witch-Hunting

Activities per Year

.575

.455

-.242

.313

.047

.042

.438

.429

Sources: Political Party System-One-, Two- and Multi-Party. Internal Security Forces-Internal

Security Forces per thousand working age population (Taylor and Hudson, 1971). Population-1960 population in millions (I.B.R.D., 1973). GNP=1960 Gross National Product, per capita (I.B.R.D., 1973).

Standard errors in parentheses.

* p<.05.

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

228

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

lated (p<.05) to the overall rate of witch

hunting, but so were the control variables.

All of the independent variables were significant at the .05 level and all the unstandardized coefficients were twice their

standard errors. The overall rate does not

seem to be a simple function of the representation of corporate or constituent

interests.

One-party countries have the highest

rate of witch-hunting activity. They have a

median 6.1 log witch-hunting activities per

year compared with only 1.6 for two-party

and 1.2 for multi-party. The large score

(Appendix 1) for the United States should

be interpreted cautiously, as it is undoubtedly inflated by the very extensive coverage the Times gives the U.S. Except for

Ghana, the African one-party states have

very little activity. Most one-party witch

hunting, therefore, was conducted by

We

have

Communist

countries.

categorized countries by party system,

but we have no way of further differentiating among Communist states as to the representation of partial or corporate interests within these one-party regimes. Some

support for the applicability of the general

theoretical argument that witch hunting is

related to representing solely the collective interest at the expense of competing

or partial interests is suggested by Hannah

Arendt. She observes that, even for oneparty Communist and Fascist states, the

further elimination of competing interests

is associated with an increase in witch

hunting and political terror.

terror increased both in Soviet Russia and

Nazi Germanyin inverse ratio to the existence of internal political opposition, so

that it looked as though political opposition

had not been the pretext of terror . . . but

the last impedimentto its full fury. [In Soviet

Russia] . .. full terrordid not breakloose in

the twenties but in the thirties, when the

opposition of the peasant classes was no

longer an active factor in the situation.Khrus-chev,too . . . notes that "extreme

repressivemeasureswere not used" against

the opposition during the fight against the

Trotskyites and the Bukharinites,but that

"the repressionagainst them began" much

later after they had long been defeated.

Terror by the Nazi regime reached its

peak duringthe war, when the Germannation was actually "united." Its preparation

goes back to 1936when all organizedinterior

resistance had vanished and Himmler proposed an expansion of the concentration

camps. (Arendt, 1973:393)

To assess more systematically the importance of Communist countries per se, as

opposed to the more general Durkheimian

idea of corporateness, one would want to

consider examining other historical forms

of one-party states, developing an indicator of corporateness other than party system, or searching for a means of differentiating, among one-party states, their

relative expression of corporate and constituent interests.

The Distribution of Subversion across

Specific Institutional Areas

We can more closely examine the distribution of witch-hunting activity by looking at the percentage distribution of ritually discovered subversion in different institutional areas (see Table 2). The Govand

ernment,

Military,

Foreigners

categories generally have the highest percentages of witch-hunting activity. If we

exclude the Religion category, because of

confounding factors for many of the

newer one-party states which will be discussed later, then these three categories

account for 64.4 percent of the total in

one-party states, 74.4 percent in twoparty states and 73.9 percent in multi-party

countries. This suggests that the creation

of subversion surrounds structures and

persons who are related in some fashion

to the distinctly corporate aspect of a

country's existence. Government and military provide the organizational structure

through which nations attain their corporate existence and seem imbued with

larger political significance and, accordingly, those who would subvert those sacred national purposes. Foreigners, on the

other hand, relate to the corporate nation

in a different manner. The very definition

of foreigners, as outsiders and nonmembers of the national collectivity, is

derived from their relationship to the corporate nation as a whole.

Multi-party states discover a very large

proportion (42 percent) of their subversion among foreigners. This could reflect

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

229

POLITICAL WITCH HUNTS

Table 2. Percent Distribution of Witch-Hunting Activities by Institutional Area and Political Party

System

Multi-Party

Two-Party

One-Party

Institutional

Area

Percent

Percent

Government

Military

Education

Economy

Intellectuals

Religion

Foreigners

26.4

4.5

11.2

5.7

10.8

21.9

19.4

549

93

233

119

225

455

402

33.1

19.3

12.2

6.6

6.4

1.9

20.6

212

124

78

42

41

12

132

15.0

15.0

9.2

3.6

12.8

1.9

42.5

54

54

33

13

46

7

153

100.0

2076

100.0

641

100.0

360

Total

the low degree to which their institutional

structuresare imbuedwith largerpolitical

significance. These countries, as nationstates, have a corporate existence, although they do not formally express as

much of their distinctly corporate interests as two- and one-partystates. Accordingly, sacred nationalpurposes are not as

extensively infused into their institutional

structures and, consequently, they conduct much of their witch hunting outside

their institutional infrastructure, e.g.,

among foreigners.

The percentages among the general

institutional categories,

Education,

Economy and Intellectuals,are all quite

similar. There is, though, a large discrepancy between the proportion of witch

hunting centering on persons from the

general category of religious groups and

institutions for one-party countries (22

percent) and two- and multi-partycountries (2 percent). This high percentagefor

one-party states could reflect the churchstate struggles involved in the nationbuilding process of those new states

which emerged following the Second

World War. Partial evidence for this is

found in comparingthe amount of witch

hunting which occurred during the early

1950-1955period for new and older oneparty states, with the latterhavingalready

passed through many of the pangs of

nation-building.The new states (China,

East Germany, Albania, Bulgaria,

Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland,

Rumania and Yugoslavia) averaged 73

their within-religiouspercent of

institutions witch hunting during the

1950-1955period. One-partystates estab-

Percent

wishedbefore 1945 (the USSR, Spain and

Portugal) averaged only seven percent of

their within-religious-institutions activity

during this early period. The new states

also accounted for some 86.6 percent of

all one-party witch hunting around religious institutions which further suggests

that most of this activity was tied to the

problems of newly emerging states.

Subversion within Government

We also can examine the proportion of

witch hunting within the four subcategories composing the general area of

government. Table 3 shows that the vast

proportion of witch hunting in government

is concentrated within national bureaucracies (one-party, 63.4 percent; twoparty, 78.8 percent; multi-party, 71.1 percent). There are, though, some interesting

differences. As the political representation of the corporate national interest is

compromised with the increasing representation of constituent group intereststhat is, moving from one- to multiparty-the proportion of subversion discovered around the national executive officer, who represents the interests of the

collectivity as a whole, gradually decreases (one-party, 20 percent; two-party,

10.4 percent; multi-party, 1.9 percent).

The inverse relationship holds for the

proportion of subversion discovered

within national legislatures. As the representation of constituent interests increases, the proportion in legislatures increases (one-party, 4.3 percent; twoparty, 6.1 percent; multi-party, 11.3 percent). It seems that where the expression

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

230

Table 3. Percent Distribution of Witch-Hunting

System

National Executive

Officer

National Bureaucracy

National Legislature

Local Government

Total

by Political Party

Multi-Party

Two-Party

One-Party

Government

Activities within Government

Percent

Percent

Percent

20.0

63.4

4.3

12.3

70

222

15

43

10.4

78.8

6.1

4.7

22

167

13

10

1.9

71.7

11.3

15.1

1

38

6

8

100.0

350

100.0

212

100.0

53

of the nation's corporate interest is

paramount (one-party) the office which

stands for the collectivity as a whole, the

nationalexecutive officer, is the source of

more subversiveactivity (20 percent)than

the legislature(4.3 percent), which is the

structure representing constituent group

interests. Conversely, where the collectivity is structuredso that constituent interests are expressed at the expense of the

corporate national interest (multi-party),

then legislatureshave a higherproportion

(11.3 percent) than the nationalexecutive

officer (1.9 percent), who represents the

now-compromisedcorporate interest. Finally, two-party countries express less

corporate interests than one-party but

more than multi-party.Consequently,they

have more witch hunting around their

executive officer than multi-party, but

less than one-partycountries, and more in

their legislatures than one-party, but less

than multi-partycountries.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Althoughthe most extreme instances of

political terror and witch hunting are associated with totalitarian regimes, the

ritualistic search for imaginary enemies

should be conceptualized as a variable,

not the singular property of totalitarian

states. The substance of the charges and

accusations and the kinds of ritual may

vary from country to country, but the

sociological process is identical. Nations,

as corporate entities, are all searching for

the same thing: the mythical enemy which

stands in symbolic opposition to the collectivity as a corporate whole.

The perpetuation of social reality

through the complex interaction of ritual

and a mythical universe populated with all

sorts of extraordinary spirits and forces is

similarly not the sole characteristic of

primitive religious systems. The penetration of the sacred into daily reality is also

a variable. Modern men also mingle and

walk among their gods and find themselves in mortal combat with the mythical

forces of Nature and History or The

People and The Nation. These are Durkheimian representations of the corporate

reality of modern societies. The more

corporate reality that is present, the

stronger, more clearly defined and more

closely merged with everyday reality are

those symbolic representations which

mirror that corporate reality. Daily life

becomes filled with transcendent political

significance and, simultaneously, the

enemies of the sacred purposes. The ritual

creation of oppositions to representations

of corporate social reality is one of the

fundamental forms of the modern religious life.

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

POLITICAL WITCH HUNTS

231

Appendix 1. Total Number of Witch-HuntingActivities by Institutional Area

Activities by InstitutionalArea

Party System

and Country

Total

Activities

Totale

3347

532

475

406

405

324

316

242

197

109

94

2076

318

300

307

288

169

195

159

108

66

51

549

88

95

57

65

55

43

52

3

27

27

93

20

7

9

15

3

13

5

1

4

1

Ghanab

90

45

15

Portugal

Albania

Senegalc

62

52

15

27

20

5

0

11

3

Guinea b

Tanzania'

10

9

6

8

6

3

One-Party

Total

China

Czechoslovakiaf

Poland

U.S.S.R.

East Germany

Hungaryg

Yugoslavia

Spain

Bulgaria

Rumania

Chadc

Ivory Coastc

Two-Party

Total

United States

Great Britain

Philippines

Australia

Austriaa

Colombiab

NewZealand

Multi-Party

Total

France

West Germanya

Italy

Sweden

Canada

Switzerland

Netherlands

Finland

Norway

Denmark

Belgium

Ireland

Iceland

Luxembourg

a

Govern- Mili- Edu- Econ- Intel- Reliment

tary cation omy lectuals gion

Foreigners'

233

23

16

43

15

42

13

16

34

9

1

119

18

22

6

27

13

8

3

14

2

0

225

19

27

49

21

3

23

36

31

3

2

455

107

57

95

39

45

49

27

19

6

8

402

43

76

48

106

8

46

20

6

15

12

5

1

0

14

1

0

2

0

0

5

0

0

1

1

0

0

6

2

1

3

0

1

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

1

5

1

4

1

3

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

1267

1040

123

34

29

25

14

2

641

507

87

20

6

15

5

1

212

166

37

6

0

1

2

0

124

99

21

2

0

0

2

0

78

70

3

3

1

1

0

0

42

38

2

2

0

0

0

0

41

35

2

0

1

3

0

0

12

11

0

1

0

0

0

0

132

88

22

6

4

10

1

1

826

275

157

103

64

51

49

25

24

22

20

20

15

1

0

360

112

53

43

29

12

30

24

18

12

15

7

5

0

0

54

23

13

4

1

2

1

2

2

0

1

1

4

0

0

54

20

1

6

7

0

1

3

2

6

7

1

0

0

0

33

8

9

4

1

3

2

3

1

0

2

0

0

0

0

13

3

5

1

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

46

27

6

6

0

2

0

1

0

0

2

1

1

0

0

7

2

1

0

0

0

0

0

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

153

29

18

22

16

5

26

15

9

6

3

4

0

0

0

1956 and later.

1958 and later

c 1950 and later.

1964 and later.

Not all activities were described completely enough to permit assignment to an institutional area.

f Because of foreign occupation, not coded during 1968.

g Because of foreign occupation, not coded during 1956.

h Combinedwith category agents of

foreign governments.

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

232

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Appendix 2. Correlation Coefficients among the Variables Party System, Internal Security Forces,

Population, per Capital GNP and Log Witch-Hunting Activities per Year (N=34)

Variables

Variables

PARTY SECFOR

Political Party System

Internal Security Forces

Population

Per Capita GNP

Log Witch-Hunting

Activities per Year

PARTY

SECFOR

POP

GNP

LWHA

1.00

.202

.149

-.701

.283

1.00

.446

.055

.314

POP

1.00

-.056

.446

GNP

Mean

S.D.

1.00

.055

2.21

21.62

44.69

829.27

5.81

.91

22.74

114.16

672.16

1.40

Appendix 3. Correlation Coefficients among the Variables Party System, Internal Security Forces,

Population, per Capital GNP and Witch-Hunting Dispersion Index (N=25)

Variables

PARTY SECFOR

Variables

Political Party System

Internal Security Forces

Population

Per Capita GNP

Log Witch-Hunting

Dispersion Index

PARTY

SECFOR

POP

GNP

WHDI

1.00

.393

.195

-.694

.460

1.00

.212

-.283

-.038

POP

1.00

-.119

.205

GNP

1.00

.294

Mean

S.D.

2.16

.94

36.44

24.10

58.88 130.85

907.16 673.58

.852

.075

REFERENCES

Danzger, M. Heroert

1976 "Validating conflict data." American

Arendt, Hannah

Sociological Review 40:570-84.

1973 The Originsof Totalitarianism.New York: Douglas, Mary

HarcourtBrace Jovanovich.

1966 Purity and Danger. Harmondsworth:PenBanks, ArthurS.

guin.

1971 Cross-PolityTime Series Data. Cambridge:

1970 Natural Symbols. New York: Pantheon.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Durkheim,Emile

Press.

1965 The Elementary Forms of the Religious

Baum, Richardand FrederickC. Teiwes

Life. Tr. J. W. Swain. New York: Free

1968 Ssu-ch'ing: The Socialist Education

Press.

Movementof 1962-1966.Berkeley:Center Erikson, Kai T.

for Chinese Studies, University of Califor1966 WaywardPuritans:A Study in the Sociolnia.

ogy of Deviance. New York: Wiley.

Bell, Daniel

Feierabend, Ivo K. and Rosalin Feierabend

1964 "Interpretationsof Americanpolitics." Pp.

1966 "Aggressive behaviors within polities,

47-73 in Daniel Bell (ed.), The Radical

1948-1962: a cross-nationalstudy." JourNew

Right.

York: Anchor.

nal of Conflict Resolution 10:249-71.

Bellah, Robert N.

Goffman,Erving

1970 Beyond Belief. New York: Harper and

1956 "The natureof deference and demeanor."

Row.

AmericanAnthropologist58:473-502.

Berger, Peter L.

Goldman,Merle

1969 The Sacred Canopy. New York: Anchor

1965 Literary Dissent in Communist China.

Books.

Cambridge:HarvardUniversity Press.

Blondel, Jean

Gurr,Ted

1973 Comparative Legislatures. Englewood

1968 "A causal model of civil strife: a comparaCliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

tive analysisusingnew indices." American

Brzezinski, ZbigniewK.

Political Science Review 62:1104-24.

1956 The PermanentPurge.Cambridge:Harvard IBRD (InternationalBank for Reconstructionand

University Press.

Development)

Cohen, Stephen F.

1973 WorldEconomic Atlas. Washington,D.C.

1971 Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution.. Kirchheimer,Otto

New York: RandomHouse.

1961 PoliticalJustice. Princeton:PrincetonUniConquest, Robert

versity Press.

1968 The Great Terror.New York: Macmillan.

S. M.

Lipset,

Dallin, Alexanderand George W. Breslauer

1955 "The radicalright:a problemfor American

1970 Political Terror in Communist Systems.

democracy." British Journalof Sociology

Ca.:

Stanford

Stanford,

University Press.

6:176-209.

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REFORM ORGANIZATIONSAND CAREERS

233

Simpson, E. H.

1949 "Measurement of diversity." Nature

163:688.

Solomon, RichardH.

1971 Mao's Revolutionand the Chinese Political

Culture.Berkeley:University of California

Press.

Swanson, Guy E.

1964 The Birth of the Gods. Ann Arbor: The

University of MichiganPress.

1967 Religionand Regime. Ann Arbor:The University of MichiganPress.

1971 "An organizational analysis of collectivities." American Sociological Review

22: 17-25.

36:607-23.

Schwartz, BenjaminI.

1968 "The reign of virtue: some broad perspec- Taylor, Charles L. and Michael C. Hudson

1971 Handbook of Political and Social Indicatives on leader and party in the Cultural

tors. Vol. II. Ann Arbor: Inter-University

Revolution." The China Quarterly 35

Consortiumfor Political Research.

(July-September):1- 17.

Luckmann,Thomas

1967 The Invisible Religion. New York: Macmillan.

MacFarquar,Roderick

1960 The Hundred Flowers Campaignand the

Chinese Intellectuals.New York: Praeger.

Parsons, Talcott

1955 "Social strainsin America." Pp. 209-38 in

Daniel Bell (ed.), The Radical Right. Garden City: Anchor.

Robinson, W. S.

1957 "The statistical measurement of agreement." American Sociological Review

SOCIAL REFORM ORGANIZATIONS AND SUBSEQUENT CAREERS

OF PARTICIPANTS: A FOLLOW-UP STUDY OF EARLY

PARTICIPANTS IN THE OEO LEGAL SERVICES PROGRAM*

HOWARD

S. ERLANGER

University of Wisconsin, Madison

American Sociological Review 1977, Vol. 42 (April):233-248

This paper considers the extent to which participation as a salaried professional in a reformoriented organization affects the participant's subsequent career. This issue is studied in the

context of one such organization, the OEO sponsored Legal Services Program, which was

probably the largest and best known organization oriented to the redistribution of professional

services in the late 1960s. Because of the paucity of literature on the consequences of participation in reform organizations, a related literature, that of the consequences of participation in

the-student movement of the sixties, is drawn upon for insight, yet also critically examined.

Comparison of the subsequent careers of 228 lawyers in Legal Services in 1967 to those of 981

other lawyers who were practicing law in 1967 indicates that participation in the program has

an important effect on both the distribution of professional services and the rendering of

reform-oriented pro bono (free or reduced fee) work. In contrast to previous studies, the

explanation offered here differentiates between various components of socialization. In addition, the importance of job market factors is stressed. A further di/Jerence from previous

wi'orkis the consideration, albeit brief, of the effects of variation in experience in the organization.

In the study of social reform

movements and organizations, a good

deal of attention has been paid to the

* This paper is part of a broader study of legal

rightsactivities in which I am collaboratingwith Joel

F. Handler and Ellen Jane Hollingsworth. I am

gratefulto them and to our earliercollaborator,Jack

Ladinsky,for their extensive work on all phases of

the project;to James Fendrich,Thomas McDonald,

Gerald Marwell and, especially, Felice Levine for

their comments on an earlier draft; to Hal

Winsborough, Arthur Goldberger and Robert

Hauserfor methodologicaladvice; andto IreneRodgers, Pramod Suratkar, Anna Wells and Nancy

Williamson for research and programmingassistance. This work was supportedby funds grantedto

the Institutefor Researchon Povertyat the University of Wisconsinby the Office of EconomicOppor-

characteristicsof participantsat the time

of entry, but relatively little to the effects

of participationon the subsequentcareers

of participants. There are many reasons

for this; most obviously, current participants are relatively easy to locate, while

former participantsare not. In addition,

much of the literatureon participationrelates to the social reform activities of the

1960s, for which it is only now practicalto

collect follow-up data.

The activism of the 1960swas most evident among college youth; hence, there is

tunity pursuantto the EconomicOpportunityAct of

1964. Responsibilityfor what follows remains with

the author.

This content downloaded from 134.129.120.3 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 06:35:33 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

- BOOK - CH1 - Two-Dimensional Man - Power and Symbolism in Complex Society (Abner Cohen)Документ9 страницBOOK - CH1 - Two-Dimensional Man - Power and Symbolism in Complex Society (Abner Cohen)Christopher TaylorОценок пока нет

- The Social Construction of The MaterialДокумент14 страницThe Social Construction of The MaterialDuarte Rosa FilhoОценок пока нет

- Dybbuk and MaggidДокумент27 страницDybbuk and MaggidMarla SegolОценок пока нет

- Must Identity Movements Self Destruct (GAMSON, J.)Документ19 страницMust Identity Movements Self Destruct (GAMSON, J.)Batista.Оценок пока нет

- Haste (2004) Constructing The CitizenДокумент29 страницHaste (2004) Constructing The CitizenaldocordobaОценок пока нет

- The Sacred' Dimension of NationalismДокумент25 страницThe Sacred' Dimension of NationalismJijoyM100% (1)

- Bahasa Inggris Fakultas Hukum Semester 1Документ54 страницыBahasa Inggris Fakultas Hukum Semester 1Pandji Purnawarman83% (6)

- Ch-6 Political PartiesДокумент9 страницCh-6 Political PartiesSujitnkbps100% (2)

- Anthropology, Sociology, Political Science PDFДокумент37 страницAnthropology, Sociology, Political Science PDFAngelica BermasОценок пока нет

- Wolinetz, S (2006) Party Systems and Party System TypesДокумент12 страницWolinetz, S (2006) Party Systems and Party System TypesOriana CarbonóОценок пока нет

- Simmel. The Concept and Tragedy of CultureДокумент13 страницSimmel. The Concept and Tragedy of CultureMihai Stelian Rusu100% (1)

- The Construction of Religion As An Anthropological CategoryДокумент28 страницThe Construction of Religion As An Anthropological CategoryGuillermo Pelaez CotrinaОценок пока нет

- Ioanid, Radu. 2004. The Sacralised Politics of The Romanian Iron GuardДокумент36 страницIoanid, Radu. 2004. The Sacralised Politics of The Romanian Iron GuardMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- The Construction of ReligionДокумент29 страницThe Construction of Religion黄MichaelОценок пока нет

- Historicizing ConstructionismДокумент11 страницHistoricizing ConstructionismZarnish Hussain100% (6)

- Jose Casanova - Private and Public ReligionsДокумент42 страницыJose Casanova - Private and Public ReligionsDeborah FrommОценок пока нет

- Presentation LijphartДокумент18 страницPresentation LijphartDungDoОценок пока нет

- Behind the Myths: The Foundations of Judaism, Christianity and IslamОт EverandBehind the Myths: The Foundations of Judaism, Christianity and IslamОценок пока нет

- Martha Finnemore Norms Culture and World Politics: Insights From Sociology's InstitutionalismДокумент24 страницыMartha Finnemore Norms Culture and World Politics: Insights From Sociology's InstitutionalismyoginireaderОценок пока нет

- Philippine Politics and Governance Quarter 2 - Module 3: Elections and Political Parties in The PhilippinesДокумент20 страницPhilippine Politics and Governance Quarter 2 - Module 3: Elections and Political Parties in The PhilippinesDonald Roland Dela TorreОценок пока нет

- Aidala (1985)Документ29 страницAidala (1985)americangurl1284681Оценок пока нет

- Haste, Helen. Constructing The CitizenДокумент28 страницHaste, Helen. Constructing The CitizenManuel Pinto GuerraОценок пока нет

- The Broken Covenant of Tito's People: The Problem of Civil Religion in Communist YugoslaviaДокумент23 страницыThe Broken Covenant of Tito's People: The Problem of Civil Religion in Communist YugoslaviaXDОценок пока нет

- Baber (2000) - RELIGIOUS NATIONALISM, VIOLENCE AND THE HINDUTVA MOVEMENT IN INDIA - Zaheer BaberДокумент17 страницBaber (2000) - RELIGIOUS NATIONALISM, VIOLENCE AND THE HINDUTVA MOVEMENT IN INDIA - Zaheer BaberShalini DixitОценок пока нет

- Ann Swidler - Culture in ActionДокумент15 страницAnn Swidler - Culture in ActionMadalina Stocheci100% (1)

- Culture & SocietyДокумент65 страницCulture & SocietyAnny YangОценок пока нет

- 2083183Документ20 страниц2083183UzpurnisОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Religiosities: Emergent Socialities and the Post-Nation-StateОт EverandContemporary Religiosities: Emergent Socialities and the Post-Nation-StateОценок пока нет

- SeidmanДокумент13 страницSeidmanCarolina Gomes de AraújoОценок пока нет

- Determinants of Human BehaviorДокумент12 страницDeterminants of Human BehaviorAnaoj28Оценок пока нет

- ESO-15 PMD PDFДокумент7 страницESO-15 PMD PDFRajni KumariОценок пока нет

- De La CadenaДокумент38 страницDe La CadenaJuanita Roca SanchezОценок пока нет

- Civilisation Hijacked: Rescuing Jesus from Christianity and the Human Spirit from BondageОт EverandCivilisation Hijacked: Rescuing Jesus from Christianity and the Human Spirit from BondageОценок пока нет

- Brubaker - Religion and Nationalism Four ApproachesДокумент19 страницBrubaker - Religion and Nationalism Four Approacheswhiskyagogo1Оценок пока нет

- Edgell - Atheists As 'Other' Moral Boundaries and Cultural Membership in American SocietyДокумент25 страницEdgell - Atheists As 'Other' Moral Boundaries and Cultural Membership in American SocietyMiltonОценок пока нет

- Rius Ulldemolins2020Документ29 страницRius Ulldemolins2020jk9yk7wqg6Оценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 132.174.253.206 On Wed, 09 Feb 2022 02:10:12 UTCДокумент54 страницыThis Content Downloaded From 132.174.253.206 On Wed, 09 Feb 2022 02:10:12 UTCFrancisco Reyes-VázquezОценок пока нет

- Shamanism The Key To ReligionДокумент26 страницShamanism The Key To Religionsatuple66Оценок пока нет

- 10 2307@2768827Документ16 страниц10 2307@2768827Shia ZenОценок пока нет

- Motyl - Bridging DividesДокумент26 страницMotyl - Bridging DividesBrandon ThomasОценок пока нет

- New Religious MovementsДокумент2 страницыNew Religious MovementsBidisha DasОценок пока нет

- Culture Against Society: F. Allan HansonДокумент5 страницCulture Against Society: F. Allan HansonBently JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Indigenous CosmopoliticsДокумент45 страницIndigenous CosmopoliticsAndra ZambranoОценок пока нет

- NRMsДокумент3 страницыNRMsBidisha DasОценок пока нет

- Communalism in Modern IndiaДокумент25 страницCommunalism in Modern IndiaAtif Wird AnwaltОценок пока нет

- The Social Construction of FrivolityДокумент11 страницThe Social Construction of Frivolityahsanniyazi62Оценок пока нет

- Popular Culture and Ideological Discontents: A Theory: Gabriel BarohaimДокумент18 страницPopular Culture and Ideological Discontents: A Theory: Gabriel BarohaimLata DeshmukhОценок пока нет

- Paine Civil Religion BisheffДокумент5 страницPaine Civil Religion BisheffboekopruimingrwsОценок пока нет

- Ingold Social Relations of The Hunter Gatherer BandДокумент18 страницIngold Social Relations of The Hunter Gatherer BandLajos SzabóОценок пока нет

- Radicalization of State and Society in Pakistan by Rubina SaigolДокумент22 страницыRadicalization of State and Society in Pakistan by Rubina SaigolAamir MughalОценок пока нет

- Neitz - Gender and Culture - Challenges To The Sociology of Religion (2004)Документ13 страницNeitz - Gender and Culture - Challenges To The Sociology of Religion (2004)LucasОценок пока нет

- Eric Wolf 1956 BrokersДокумент15 страницEric Wolf 1956 BrokersDiana GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Ucsp PowerpointДокумент32 страницыUcsp PowerpointJergen Mae BarutОценок пока нет

- 10 - Politics, Society and IDДокумент5 страниц10 - Politics, Society and IDEmre ArОценок пока нет

- Human Rights Religious Conflict and GloДокумент18 страницHuman Rights Religious Conflict and GloAhmad kamalОценок пока нет

- Political Sociology PresentationДокумент4 страницыPolitical Sociology PresentationAtalia A. McDonaldОценок пока нет

- Turner PilgrimageДокумент41 страницаTurner PilgrimageDaintryОценок пока нет

- Mission in The Context of ReligiousДокумент9 страницMission in The Context of ReligiousJasmine SornaseeliОценок пока нет

- Secularization of PostmillenialismДокумент21 страницаSecularization of PostmillenialismJames RuhlandОценок пока нет

- Dewey, Liberal MoralityДокумент23 страницыDewey, Liberal MoralityAnonymous Pu2x9KVОценок пока нет

- GOUSGOUNIS Anastenaria & Transgression of The SacredДокумент14 страницGOUSGOUNIS Anastenaria & Transgression of The Sacredmegasthenis1Оценок пока нет

- On Civil SocietyДокумент22 страницыOn Civil Society李璿Оценок пока нет

- Running Head: The Necessary Removal 1Документ9 страницRunning Head: The Necessary Removal 1Muhammad Bilal AfzalОценок пока нет

- Rusu, M. S. (2020) - Geographies of Remembrance (Holocaust Memoryscapes) - Cuprins - ReferinteДокумент12 страницRusu, M. S. (2020) - Geographies of Remembrance (Holocaust Memoryscapes) - Cuprins - ReferinteMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Guyot, S., & Seethal, C. (2007) - Identity of Place, Places of IdentitiesДокумент10 страницGuyot, S., & Seethal, C. (2007) - Identity of Place, Places of IdentitiesMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- The Soviet and The Post-Soviet: Street Names and National Discourse in AlmatyДокумент23 страницыThe Soviet and The Post-Soviet: Street Names and National Discourse in AlmatyMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Vander W Us Ten 2001Документ6 страницVander W Us Ten 2001Mihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Azaryahu, M. 1990. Renaming The Past. City TextДокумент23 страницыAzaryahu, M. 1990. Renaming The Past. City TextMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Misztal. 2016. Sociological Imagination and Literary IntuitionДокумент24 страницыMisztal. 2016. Sociological Imagination and Literary IntuitionMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Holton. 1995. Coleman and Rational Choice TheoryДокумент20 страницHolton. 1995. Coleman and Rational Choice TheoryMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Rusu, M.S. 2014. Literary Fiction and Social ScienceДокумент20 страницRusu, M.S. 2014. Literary Fiction and Social ScienceMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Rusu, M.S. 2014. (Hi) Story-Telling The Nation PDFДокумент20 страницRusu, M.S. 2014. (Hi) Story-Telling The Nation PDFMihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Kafka and Weber 01Документ17 страницKafka and Weber 01Mihai Stelian RusuОценок пока нет

- Sartori SpartiesandpartysystemsДокумент2 страницыSartori SpartiesandpartysystemsJinu KimОценок пока нет

- MULTIPLE CHOICE: Read The Following Statements Carefully Then Encircle The Letter of The Correct AnswerДокумент3 страницыMULTIPLE CHOICE: Read The Following Statements Carefully Then Encircle The Letter of The Correct AnswerRienalyn GalsimОценок пока нет

- Popular Struggles and MovementsДокумент10 страницPopular Struggles and Movementsthinkiit100% (1)

- Multi Party SystemДокумент2 страницыMulti Party Systemqwaszx1234321Оценок пока нет

- Multi Party System Pol SCДокумент20 страницMulti Party System Pol SCKanchan VermaОценок пока нет

- Comparatively Discuss Between Bi-Party and Multi-Party Systems, Which One Is Most Applicable For Bangladesh and Why?Документ2 страницыComparatively Discuss Between Bi-Party and Multi-Party Systems, Which One Is Most Applicable For Bangladesh and Why?Iftekhar AhmedОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 PDFДокумент35 страницChapter 2 PDFAjab SinghОценок пока нет

- Reading ComprehensionДокумент3 страницыReading ComprehensionGainna Racy DaintyОценок пока нет

- MateriДокумент56 страницMateriPutri Kurnia EsaОценок пока нет

- Proportional RepresentationДокумент3 страницыProportional RepresentationMaria Karen LayloОценок пока нет

- 2party SysДокумент6 страниц2party SystanpopohimeОценок пока нет

- A Two Party System in UKДокумент4 страницыA Two Party System in UKdjetelina18Оценок пока нет

- Political Parties and Party SystemДокумент2 страницыPolitical Parties and Party SystemShannine Kaye RoblesОценок пока нет

- Key Concepts: Chapter 6 - Political Parties, Class 10, SST: What Is A Political Party?Документ6 страницKey Concepts: Chapter 6 - Political Parties, Class 10, SST: What Is A Political Party?Sandeep SinghОценок пока нет

- Ch-6 Political Parties 2023-24Документ7 страницCh-6 Political Parties 2023-24ccard4452Оценок пока нет

- Political Partiesand Party Systems ForpublicationДокумент10 страницPolitical Partiesand Party Systems ForpublicationYashОценок пока нет

- 1972 - Duverger - Factors in A Two-Party and Multiparty SystemДокумент4 страницы1972 - Duverger - Factors in A Two-Party and Multiparty SystemRafael MoreiraОценок пока нет