Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Management of Impacted Maxillary Canines Using Mandibular Anchorage

Загружено:

drsankhyaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Management of Impacted Maxillary Canines Using Mandibular Anchorage

Загружено:

drsankhyaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CLINICIANS CORNER

Management of impacted maxillary canines using mandibular

anchorage

Pramod K. Sinha, DDS, BDS, MS,a and Ram S. Nanda, DDS, MS, PhDb

Spokane, Wash and Oklahoma City, Okla

rthodontic management of impacted

maxillary canines can be very complex and requires a

carefully planned interdisciplinary approach. These

teeth are surgically exposed and moved toward the arch

wire after the maxillary arch is stabilized by progressing to a rigid arch wire. This movement is accomplished by bonding some form of orthodontic attachment to the exposed tooth and application of traction to

move the impacted tooth in a desired direction.

Frequently, when the palatally impacted canine is

surgically exposed, the lingual surface of the tooth is

visible and hence presents as the only available surface

for bonding attachments. The orthodontic force to be

applied to this bonded attachment requires careful planning for the following reasons:

1. An orthodontic force applied from the adjacent maxillary teeth will tend to embed the facial surface of the

crown and may create periodontal problems. This can

be prevented by first erupting the tooth vertically and

once a facial attachment can be bonded, forces should

be applied to position the tooth facially.

2. Initial leveling and aligning followed by progression of

wires to reach a rigid rectangular arch wire in the maxillary arch is required before uncovering the impacted

tooth and application of traction as described above.

3. In cases where additional room is required for the

impacted tooth, space has to be created during the

process of arch wire progression prior to the uncovering procedure.

4. Anatomic obstructions may involve the fabrication of

auxiliaries numerous times during the traction process

to redirect forces and therefore the path of eruption, or

may require frequent adjustments to do the same.

A variety of techniques have been used in the vertical movement of these teeth.1-4 Most techniques1-3 have

used the maxillary arch as anchorage for traction, which

may be unsuitable in many clinical situations. Different

clinical situations present with impacted canines being

positioned in a variety of angulations and locations.

From the Department of Orthodontics, University of Oklahoma. aClinical Assistant Professor.

bProfessor and Chairman.

Reprint requests to: Dr. Pramod K. Sinha, E 936 Calkins Drive, Spokane, WA

99208

Copyright 1999 by the American Association of Orthodontists.

0889-5406/99/$5.00 + 0 8/1/93694

254

Therefore, appliances designed to erupt these teeth

should have the versatility to allow a change in direction

of traction quickly and easily. This may prevent deleterious effects like resorption of roots of adjacent teeth

and physical obstruction as a result of anatomic limitations from slowing the progress of treatment.

Hence, the purpose of this article is to describe a technique using the mandibular arch as an anchorage unit to

vertically erupt impacted maxillary canines. This technique utilizes a mandibular fixed lingual arch as opposed

to a removable appliance presented in an earlier report.4

The lingual arch can be prepared with a vertical hook

bent in the lingual arch during its fabrication before soldering, or hooks can be soldered to the arch for the same

purpose (Fig 1). Elastics are engaged in these vertical

hooks and to the attachment on the impacted teeth for the

required traction. In addition, directional forces can be

used by applying elastics in a Class II direction as

required. One case will be presented to demonstrate this

technique for the impacted maxillary canine.

TECHNIQUE

A thorough evaluation of the pretreatment orthodontic records should accompany clinical examination

for every patient. These patients require additional

radiographs to properly locate the impacted teeth. In

some cases, the impacted canine may lie close to the

roots of the lateral incisors where it is prudent to move

the canine away from the root of the incisor before

engaging the lateral incisor bracket.

After consultations with the surgery team and formulation of a treatment plan, the following sequence of

events are planned for these patients:

1. The maxillary and mandibular teeth are banded and

bonded. A mandibular impression is made to fabricate

a mandibular lingual arch to be soldered from the first

molar band on one side to the first molar band on the

other side. The mandibular lingual arch is cemented in

place after fabrication.

2. After adequate space is opened, it is maintained with a

closed/open coil spring. In some cases, the space for the

unerupted tooth may be available and traction may be

applied from the first day because other teeth are not

involved in the anchorage unit. Alternatively, space

opening and traction may be applied simultaneously.

Sinha and Nanda 255

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

Volume 115, Number 3

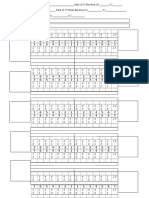

Fig 1. Fixed lingual arch with soldered hooks.

Fig 3. Intraoral right lateral view of dentition in occlusion

shows retained right maxillary primary canine.

Fig 4. Panoramic radiograph shows impacted right maxillary canine.

Fig 2. Elastic traction applied to bonded attachments.

CASE PRESENTATION

Diagnosis

3. Surgical exposure is performed and a button with a hook

fabricated from 0.010 or 0.012 inch stainless steel ligature wire is bonded using composite resin. For areas that

are difficult to isolate, recently introduced hydrophilic

primers can be used to successfully attach appliances.

4. Traction with light forces is applied via directional elastics as shown in Fig 2. The elastic size can vary to ensure

the delivery of forces that range from 40 to 60 g based

on the movements of the mandible. The elastic application is demonstrated to the patient, and a proficiency

check is done a week after the surgical procedure.

5. The canine is guided vertically toward the occlusal

plane. An orthodontic bracket should be bonded on the

labial surface of this tooth as soon as possible.

The lingual arch is fabricated with 0.036 inch

stainless steel wire. Vertical hooks (5 to 6 mm in

length) can also be fabricated by bending the 0.036

wire on itself. It is important to avoid excessive forces

to erupt the tooth. Hence, elastics should be carefully

monitored for the magnitude of forces applied.

A Caucasian female presented with a chronologic

age of 17 years 10 months (Figs 3 and 4). She had an

anterior divergent, straight facial profile (facial angle of

94, angle of convexity of + 0.5). Her SNA value was

89 and her SNB value was 86 leading to an ANB

value of + 3. She had a Class I molar relationship, with

the right maxillary canine impacted palatally. Her right

and left maxillary primary canines were overretained.

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to bring the right

maxillary canine into proper position and maintain the

Class I molar relationship and facial profile.

Treatment plan and sequence

A treatment plan that involved the extraction of the

primary canines and surgical exposure of the impacted

right maxillary canine followed by directional forces to

bring it into occlusion was presented and accepted. A

256 Sinha and Nanda

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

March 1999

Fig 6. Intraoral frontal view of dentition in finished

occlusion.

Fig 5.Three-quarter smile photograph shows finished

occlusion.

Fig 7. Intraoral right lateral view of dentition in occlusion.

consultation was done for the surgical exposure of the

permanent canine before starting treatment. The primary canines were extracted after which appliances were

bonded on the maxillary and mandibular arches. A

mandibular lingual arch similar to the one described

earlier was placed in the mandibular arch. Surgical

exposure was performed, and an appliance identical to

the one shown in Fig 2 was bonded on the exposed surface of the unerupted teeth. Because the crown of this

tooth was in close proximity to the roots of the lateral

incisors, it was decided to replace the flap over the

crown and allow the hook to be exposed for force application. Light orthodontic forces were applied with elastics hooked to the mandibular lingual arch. The patient

was directed to use the elastics at all times except while

eating. Sequential arch wire changes were done in the

upper and lower arches and, vertical elastics were used

as needed. The canines were erupted in the palate and

were moved in the space opened for it in the maxillary

arch. The case was completed and the final result is

presented in Figs 5-7.

DISCUSSION

Palatally impacted canine teeth present unique

challenges to orthodontists. These ectopically placed

teeth have generated an array of treatment mechanics

to facilitate successful eruption of these teeth into

proper occlusion.

The mandibular lingual arch can be cemented

before the placement of any other orthodontic appliances; this allows traction on impacted teeth independent of the leveling and alignment of the arches. The

button that is bonded to the unerupted tooth has a 0.012

inch ligature wire twisted to form a hook for elastic

engagement. The maxillary and mandibular arches are

banded and bonded, and sequential arch wire changes

progressing to rigid stainless steel wires are achieved in

both arches. Spaces are opened in the maxillary arches

for the final positioning of the impacted teeth. These

spaces are maintained by using closed-coil springs.

Once the canine is erupted, an orthodontic bracket is

Sinha and Nanda 257

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

Volume 115, Number 3

bonded on the labial surface of the tooth. Different

methods can be used to bring the palatally positioned

tooth toward the buccal surface. Elastic threads or elastomeric chains can be used from the rigid maxillary

arch wire. We used a flexible arch wire such as 0.014

nickel titanium that is engaged in the canine bracket and

is tied over the rigid maxillary arch wire. This flexible

wire can extend from an auxiliary tube on the first molar

or can be tied over the conventional buccal molar tube.

The canine tooth is allowed to approach the rigid maxillary wire until the bracket touches the rigid arch wire.

The maxillary wire is then replaced with a flexible arch

wire to achieve the desired position of the tooth.

The purpose of this article is to present a technique

used successfully by the authors in their day to day

practice. It is relatively simple to use requiring no complex wire bending and, with relatively few side effects.

The advantages of this technique are in its simplicity in

appliance design and application. Further, forces can be

used before the alignment of arches, which may significantly reduce overall treatment time. However, careful

monitoring of the unerupted tooth is required to change

the direction of the forces as required. As is evident, the

practitioner has the ability to easily change the direction of the force by demonstrating the use of elastics

from molar hooks.

Another clinical situation that presents a variety of

problems involves cases in which the maxillary canines

are impacted and crowding is sufficient to decide on an

extraction treatment plan. The clinician is confronted

with the following questions: Which teeth should be

extracted? Is the canine ankylosed? or, Is the tooth

going to respond favorably with elastic traction? To

answer these questions, the practitioner has to ensure

that the canine will move on the application force. However, this is difficult to do when leveling and aligning is

not accomplished. In these situations, we have found

that this technique is very useful in that the lingual arch

can be cemented and elastic traction can be applied

after the surgical uncovering of the canines. The decision to extract or not to extract the impacted tooth

becomes clear on evaluating movement of the tooth.

We have not experienced problems with this technique; however, a few potential problems can be suggested as possible in treatment. One of the key elements

in any form of tooth movement is the magnitude of

forces. Similarly, in this technique the force magnitude

is important and should not exceed 40 to 60 g. A high

force level may produce unwanted movements of the

mandibular teeth, particularly the molars. This technique

also involves the use of elastics controlled by patient

compliance, which may pose a problem in some cases.

CONCLUSIONS

1. The mandibular fixed lingual arch can be an effective

anchorage source for vertical eruption of impacted

maxillary canines.

2. The technique presented can be used in all cases with

impactions.

3. It may be particularly useful in the following situations:

in cases when a confirmation of ankylosis of the

impacted tooth is suspected and extraction decisions need to be made.

The movement of the impacted tooth monitored on

radiographs can provide cues to diagnostic decisions, and, in cases where the maxillary arch is

unsuitable for providing anchorage.

REFERENCES

1. Fournier A, Turcotte J-Y. Bernard C. Orthodontic considerations in the treatment of

maxillary impacted canines. Am J Orthod 1982;81:236-9.

2. Bishara SE. Impacted maxillary canines: a review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

1992;101:159-71.

3. Kornhauser S, Abed Y, Harari D, Becker A. The resolution of palatally impacted

canines using palatal-occlusal force from a buccal auxiliary . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996;110:528-34.

4. Orton HS, Garvey MT, Pearson MH. Extrusion of the ectopic maxillary canine using

a lower removable appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1995;107:349-59.

Вам также может понравиться

- Treatment Planning Single Maxillary Anterior Implants for DentistsОт EverandTreatment Planning Single Maxillary Anterior Implants for DentistsОценок пока нет

- Management of Impacted Maxillary Canines Using Mandibular AnchorageДокумент4 страницыManagement of Impacted Maxillary Canines Using Mandibular AnchorageplsssssОценок пока нет

- 2007 - Intrusion of Overerupted Molars byДокумент7 страниц2007 - Intrusion of Overerupted Molars byTien Li AnОценок пока нет

- Canine Impaction Different MethodsДокумент11 страницCanine Impaction Different MethodsMSHОценок пока нет

- DriftodonticsДокумент2 страницыDriftodonticssweetieОценок пока нет

- DriftodonticsДокумент2 страницыDriftodonticssweetie0% (1)

- Kokich CaninosДокумент6 страницKokich CaninosMercedes RojasОценок пока нет

- Molares InclinadosДокумент13 страницMolares Inclinadosmaria jose peña rojas100% (1)

- Occlusion in Partial Dentures: by Prof. Dr. Osama BarakaДокумент12 страницOcclusion in Partial Dentures: by Prof. Dr. Osama BarakaEsmail AhmedОценок пока нет

- The "Ballista Spring" System For Impacted Teeth: Genevu. SwitzerlandДокумент9 страницThe "Ballista Spring" System For Impacted Teeth: Genevu. Switzerlandapi-26468957100% (1)

- The Use of Non Rigid Connectors in Fixed Partial Dentures With Pier Abutment: A Case ReportДокумент4 страницыThe Use of Non Rigid Connectors in Fixed Partial Dentures With Pier Abutment: A Case ReportIOSRjournal100% (1)

- Implicaciones Periodontales Del Tratamiento Quirúrgico-OrtodónticoДокумент9 страницImplicaciones Periodontales Del Tratamiento Quirúrgico-OrtodónticoAlfredo NovoaОценок пока нет

- Unconventional Fixed Partial Denture: A Simple Solution For Aesthetic RehabilitationДокумент4 страницыUnconventional Fixed Partial Denture: A Simple Solution For Aesthetic RehabilitationAdvanced Research PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Chung2010 PDFДокумент12 страницChung2010 PDFsmritiОценок пока нет

- Forced Eruption of Adjoining Maxillary Premolars Using A Removable Orthodontic Appliance: A Case ReportДокумент4 страницыForced Eruption of Adjoining Maxillary Premolars Using A Removable Orthodontic Appliance: A Case Reportikeuchi_ogawaОценок пока нет

- Delayed Formation of Multiple Supernumerary TeethДокумент6 страницDelayed Formation of Multiple Supernumerary TeethsauriuaОценок пока нет

- Indicaciones para ColgajoДокумент22 страницыIndicaciones para ColgajoSpaceWord 369Оценок пока нет

- Clinical: Use of Distal Implants To Support and Increase Retention of A Removable Partial Denture: A Case ReportДокумент4 страницыClinical: Use of Distal Implants To Support and Increase Retention of A Removable Partial Denture: A Case ReportDentist HereОценок пока нет

- Intermediate Denture Technique: Jack H. Rayson, D.D.S., and Robert C. Wesley, D.M.D.Документ8 страницIntermediate Denture Technique: Jack H. Rayson, D.D.S., and Robert C. Wesley, D.M.D.kelompok cОценок пока нет

- IRA Klein,: Mmedmte Denture ServiceДокумент11 страницIRA Klein,: Mmedmte Denture ServiceClaudia AngОценок пока нет

- Root Perforation Associated With The Use of A Miniscrew Implant Used For Orthodontic AnchorageДокумент11 страницRoot Perforation Associated With The Use of A Miniscrew Implant Used For Orthodontic AnchorageSALAHEDDINE BLIZAKОценок пока нет

- E1 MJAFImaxexpansionusingquadhelixinclp2009Документ5 страницE1 MJAFImaxexpansionusingquadhelixinclp2009ريام الموسويОценок пока нет

- Eruptive AnomaliesДокумент65 страницEruptive AnomaliesBenet BabuОценок пока нет

- Fabrication of Conventional Complete Dentures For A Left Segmental MandibulectomyДокумент4 страницыFabrication of Conventional Complete Dentures For A Left Segmental MandibulectomyIndrani DasОценок пока нет

- 4353 17293 1 PBДокумент2 страницы4353 17293 1 PBSwagata DebОценок пока нет

- Combined Surgical and Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Maxillary CaninesДокумент9 страницCombined Surgical and Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Maxillary CaninesAnda MateșОценок пока нет

- Space ManagementДокумент11 страницSpace Managementdr parveen bathla100% (1)

- DownloadДокумент15 страницDownloadhasan nazzalОценок пока нет

- Single Complete DentureДокумент12 страницSingle Complete DentureHarsha Reddy100% (1)

- A Fixed Guide Flange Appliance For HemimandibulectomyДокумент4 страницыA Fixed Guide Flange Appliance For HemimandibulectomyRohan GroverОценок пока нет

- Scissors Bite-Dragon Helix ApplianceДокумент6 страницScissors Bite-Dragon Helix ApplianceGaurav PatelОценок пока нет

- Implants in OrthodonticsДокумент13 страницImplants in OrthodonticsAnant JyotiОценок пока нет

- Mclaughlin2003 PDFДокумент19 страницMclaughlin2003 PDFSreeramnayak MalavathuОценок пока нет

- International Dental and Medical Journal of Advanced ResearchДокумент5 страницInternational Dental and Medical Journal of Advanced ResearchShirmayne TangОценок пока нет

- Severe Gingival Recession Caused by Orthodontic Rubber Band: A Case ReportДокумент5 страницSevere Gingival Recession Caused by Orthodontic Rubber Band: A Case ReportanjozzОценок пока нет

- The Swing Lock Denture: 1-Too Few Remaining Teeth For A Conventional DesignДокумент9 страницThe Swing Lock Denture: 1-Too Few Remaining Teeth For A Conventional DesignEsmail AhmedОценок пока нет

- Forced EruptionДокумент4 страницыForced Eruptiondrgeorgejose7818Оценок пока нет

- Vertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseДокумент13 страницVertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseLisbethОценок пока нет

- Excellence in Loops - Some ReflectionsДокумент3 страницыExcellence in Loops - Some ReflectionsKanish Aggarwal100% (2)

- Pi Is 0889540615013311Документ5 страницPi Is 0889540615013311msoaresmirandaОценок пока нет

- Gigi Tiruan GasketДокумент5 страницGigi Tiruan GasketGus BasyaОценок пока нет

- AJODONovember 2016Документ13 страницAJODONovember 2016garciadeluisaОценок пока нет

- I014634952 PDFДокумент4 страницыI014634952 PDFGowriKrishnaraoОценок пока нет

- Becker OMCarticleДокумент11 страницBecker OMCarticleRaudhatul MaghfirohОценок пока нет

- Full Mouth Rehabilitation of The Patient With Severly Worn Out Dentition A Case Report.Документ5 страницFull Mouth Rehabilitation of The Patient With Severly Worn Out Dentition A Case Report.sivak_198100% (1)

- Prosthetic Rehabilitation of Maxillectomy Patient With Telescopic DenturesДокумент6 страницProsthetic Rehabilitation of Maxillectomy Patient With Telescopic DenturesVero AngelОценок пока нет

- Imediate 4Документ3 страницыImediate 4Alifia Ayu DelimaОценок пока нет

- En-Masse Protraction of Mandibular Posterior Teeth Into Missing Mandibular Lateral Incisor Spaces Using A Fixed Functional ApplianceДокумент12 страницEn-Masse Protraction of Mandibular Posterior Teeth Into Missing Mandibular Lateral Incisor Spaces Using A Fixed Functional ApplianceNingombam Robinson SinghОценок пока нет

- Retrospective Study On Efficacy of Intermaxillary Fixation ScrewsДокумент3 страницыRetrospective Study On Efficacy of Intermaxillary Fixation ScrewsPorcupine TreeОценок пока нет

- 10 1016@j Prosdent 2020 03 025Документ6 страниц10 1016@j Prosdent 2020 03 025prostho booksОценок пока нет

- Article-PDF-sheen Juneja Aman Arora Shushant Garg Surbhi-530Документ3 страницыArticle-PDF-sheen Juneja Aman Arora Shushant Garg Surbhi-530JASPREETKAUR0410Оценок пока нет

- AbstractsДокумент5 страницAbstractsElham ZareОценок пока нет

- Extrusion Splint Technique in Management of Dental Trauma: A Case ReportДокумент5 страницExtrusion Splint Technique in Management of Dental Trauma: A Case ReportdrvarunmalhotraОценок пока нет

- Three-Dimensional Evaluation of Tooth MovementДокумент10 страницThree-Dimensional Evaluation of Tooth MovementAndrea Cárdenas SandovalОценок пока нет

- Ankylosed Teeth As Abutments For Maxillary Protraction: A Case ReportДокумент5 страницAnkylosed Teeth As Abutments For Maxillary Protraction: A Case Reportdrgeorgejose7818Оценок пока нет

- Controlled Tooth Movement To Correct An Iatrogenic Problem: Case ReportДокумент8 страницControlled Tooth Movement To Correct An Iatrogenic Problem: Case ReportElla GolikОценок пока нет

- The 2 X 4 Appliance McKeown SandlerДокумент4 страницыThe 2 X 4 Appliance McKeown Sandlervefiisphepy83312Оценок пока нет

- TMP 371 BДокумент4 страницыTMP 371 BFrontiersОценок пока нет

- Sumit 5Документ65 страницSumit 5drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Sumit 2Документ6 страницSumit 2drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- SumitДокумент8 страницSumitdrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Program Schedule Day 1Документ3 страницыProgram Schedule Day 1drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Brochure Final 1Документ1 страницаBrochure Final 1drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Mini ScrewsДокумент29 страницMini ScrewsdrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Orthoplay Patient Education Software IДокумент12 страницOrthoplay Patient Education Software IdrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Angle OrthodontistДокумент9 страницAngle OrthodontistdrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- TerminologyДокумент9 страницTerminologydrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Moving Matrix 22Документ2 страницыMoving Matrix 22drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Class 2 Div 1 of 2Документ52 страницыClass 2 Div 1 of 2drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Cogs - BurstoneДокумент3 страницыCogs - BurstonedrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Patient Status 10th JuneДокумент3 страницыPatient Status 10th JunedrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Ug BDS ReguДокумент44 страницыUg BDS RegudrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Journal of Oral Rehab PDFДокумент8 страницJournal of Oral Rehab PDFdrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- MAX4Документ9 страницMAX4drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- VirtualDJ 7 - Getting Started PDFДокумент11 страницVirtualDJ 7 - Getting Started PDFSanthia MoralesОценок пока нет

- Carey's Analysis:: Discrepancy InferenceДокумент1 страницаCarey's Analysis:: Discrepancy InferencedrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Inspection Replacement or RepairДокумент1 страницаInspection Replacement or RepairdrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Bjorks AnalysisДокумент1 страницаBjorks AnalysisdrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Acta Odontologica Scandinavica: Please Scroll Down For ArticleДокумент8 страницActa Odontologica Scandinavica: Please Scroll Down For ArticledrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- 905073120Документ7 страниц905073120drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- 906060300Документ7 страниц906060300drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Bracket Placement History 13Документ1 страницаBracket Placement History 13drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- CHECKLISTS For SeminarДокумент1 страницаCHECKLISTS For SeminardrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- 904223479Документ6 страниц904223479drsankhyaОценок пока нет

- George Gauge BrochureДокумент2 страницыGeorge Gauge BrochuredrsankhyaОценок пока нет

- Congenitally Missing Maxillary Lateral IncisorsДокумент56 страницCongenitally Missing Maxillary Lateral Incisorsdrsankhya100% (1)

- Soal-Soal LCC Bahasa Inggris SMPДокумент33 страницыSoal-Soal LCC Bahasa Inggris SMPazkhaz91% (34)

- Landslide and Sinkhole 2Документ27 страницLandslide and Sinkhole 2merrylace sanjuanОценок пока нет

- Reading - Fill in The BlankДокумент8 страницReading - Fill in The BlankHoa TruongОценок пока нет

- Eled 440 FiinalДокумент15 страницEled 440 Fiinalapi-348049660Оценок пока нет

- Middle School Geology Unit Concept MapДокумент1 страницаMiddle School Geology Unit Concept MaprebbiegОценок пока нет

- Rock & Gem - May 2016Документ84 страницыRock & Gem - May 2016Alvaro Madrid100% (2)

- Assessment Quiz in Earth ScienceДокумент4 страницыAssessment Quiz in Earth ScienceArzjohn Niel BritanicoОценок пока нет

- 4th Grading ExamДокумент3 страницы4th Grading ExamJannice Coscolluela CanlasОценок пока нет

- UNSMA2008INGP44-2011-01 New 01Документ8 страницUNSMA2008INGP44-2011-01 New 01Zenius EducationОценок пока нет

- The Hollow EarthДокумент22 страницыThe Hollow Earthmoderatemammal100% (2)

- Igneous Rocks: (C) Earth, An Introduction To Physical Geology 11 Ed. - Tarbuck, Lutgens, TasaДокумент23 страницыIgneous Rocks: (C) Earth, An Introduction To Physical Geology 11 Ed. - Tarbuck, Lutgens, TasaAlex CoОценок пока нет

- Primary Science FPDДокумент10 страницPrimary Science FPDapi-451107029Оценок пока нет

- Rinjani Trekking BBДокумент2 страницыRinjani Trekking BBKenvin SugiantoОценок пока нет

- MT ST HelensДокумент2 страницыMT ST Helensapi-235617848Оценок пока нет

- Pablo Borbon Main II, Alangilan Batangas City WWW - Batstate-U.edu - PH Tel. No. (043) 425-0139 Loc. 118Документ8 страницPablo Borbon Main II, Alangilan Batangas City WWW - Batstate-U.edu - PH Tel. No. (043) 425-0139 Loc. 118Sana NgaОценок пока нет

- Sidoarjo Mud FlowДокумент9 страницSidoarjo Mud Flowkusumawi2311Оценок пока нет

- How Mountains FormДокумент3 страницыHow Mountains Formapi-321767399Оценок пока нет

- MagmatismДокумент12 страницMagmatismVea Patricia Angelo100% (1)

- Baba Vanga - Bulgarian Nostradamus' Predicted ISIS, 9 - 11, Fukushima - PDFДокумент6 страницBaba Vanga - Bulgarian Nostradamus' Predicted ISIS, 9 - 11, Fukushima - PDFGunars100% (1)

- 2023 - Ring of Fire Mapping Activity PDFДокумент3 страницы2023 - Ring of Fire Mapping Activity PDFBrookie Childress0% (1)

- Succession PogilДокумент6 страницSuccession Pogilapi-2838014320% (2)

- 1 - Restless Earth UPDATEDДокумент4 страницы1 - Restless Earth UPDATEDMROHANLONОценок пока нет

- Geotechnical Hazards and Disaster Mitigation TechnДокумент10 страницGeotechnical Hazards and Disaster Mitigation TechnClarence De LeonОценок пока нет

- NAMEДокумент14 страницNAMEleslie capedingОценок пока нет

- DLL Science 10 Quarter 1 Week 10Документ4 страницыDLL Science 10 Quarter 1 Week 10Varonessa MintalОценок пока нет

- 6.E.2 - Earth Systems Structures and ProcessesДокумент6 страниц6.E.2 - Earth Systems Structures and ProcessesLynn BradleyОценок пока нет

- Philippines' Geographical Setting Kenneth Rae A. QuirimoДокумент2 страницыPhilippines' Geographical Setting Kenneth Rae A. QuirimoKenneth Rae QuirimoОценок пока нет

- Chemistry FoundationДокумент7 страницChemistry Foundationkhalison khalidОценок пока нет

- Plate Tectonics Question and AnswerДокумент2 страницыPlate Tectonics Question and AnswerValaria stoneОценок пока нет

- Field 2008Документ43 страницыField 2008sigitsuryaОценок пока нет