Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Hesmondhalgh, Why Music Matters Notes

Загружено:

Richard ClareИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Hesmondhalgh, Why Music Matters Notes

Загружено:

Richard ClareАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

David Hesmondhalgh Why Music Matters (Aesthetics Week 4)

Check out Richard Shusterman

The fact that music matters so much to so many people may derive from

two contrasting yet complementary dimensions of musical experience in

modern societies. The first is that music often feels intensely and

emotionally linked to the private self The second is that music is often

the basis of collective, public experiences. (1-2)

music provides a basis of self-identity and collective identity often

at the same moment. (2)

Especially complex today because the distinction between the public and

the private has never been so blurred and complex.

Hesmondhalgh offering a critical defense of music as an artistically and

socially valuable phenomenon in the face of the fetishization of

economic value that has emerged with neoliberalism. Value of art needs

defending in wake of austerity.

o However, other critiques of music (and art more broadly) have been

more valid Bourdieu et als suggestion that divisions between

high and low culture draw upon and reinforce patterns of social

inequality, and on how therefore the dominant ways of thinking

about beauty and pleasure in modern societies are deeply

compromised (4).

Value judgements re: aesthetic value and beauty are informed by existing

power relations such evaluations are surely connected to long histories

of inequality and violence. Gender and class inequality infect prevailing

judgements of aesthetic worth. (4)

Part of Hesmondhalghs defence employs Nussbaums conception of the

self and musics role in aiding personal flourishing; focusing also on

dancing and popular music, he suggests that at an individual level music

can contribute to revitalization and a healthy loss of self-consciousness.

(6)

Suggests that contemporary emphases on the role of music in everyday

life are often uncritical and overplay musics capacity to enrich peoples

lives (by overlooking the profound impact of social inequality etc., upon

human flourishing). (6)

o Competitive individualism as a (negative?) factor in peoples

relations to music (this could be useful)

So, a qualified endorsement of musics enriching potential.

Suggests that influential writings on music and community aspire to

impossible levels of communality and argues instead that we need to

look for beneficial experiences of sociability in life as it is currently lived.

(8) The need many writers feel for an ideal form of communitarian music

leads to many valuable collective musical experiences being overlooked.

Hesmondhalgh wants to reassert the liberatory potential of aesthetic

experience based on commonality across different communities in a way

similar to Ranciere and Garnham (in the face of thorough critiques by

Marxists, post-structuralists and social scientists.

o He sees the aesthetic-political value of music in the sociability that

musical culture, and the discussion and shared experience of

music, precipitates the sustenance of a public sociability, which

keeps alive feelings of solidarity and community. In this and in other

ways too, musical culture develops values and identities that feed

into deliberation, democracy, and politics in substantial but rather

indirect ways. (10)

Examines nationalism and cosmopolitanism.

o Finally, and more pessimistically, drawing on the work of

Paul Gilroy, I discuss how the inspiring cosmopolitanism of

Afro-diasporic music has been affected by

commercialization and globalization in the neo-liberal era.

Musics ability to unite people across space and time, and thereby

enable their collective flourishing, I conclude, is real, but specific,

and highly vulnerable to systemic changes, such as increasing

consumerism, commodification, and competitiveness. (10)

Feeling and Flourishing

In 19th C, aesthetic appraisals of music moved away from earlier concerns

with values and ethics [towards] a type of aesthetics that was centred

on the question of how form creates beauty. (12)

Subsequently, structure became privileged in analysis, and the imitation,

arousal and expression of emotion in music was primarily theorized in

terms of structured arousals of anticipation and deferral and the roles of

context and association of meaning in producing emotions in listeners

were sidelined. (12)

Affect theory pointed out that bodily and personal responses to (cultural)

experience are complex and go beyond the limitations of an excessive

focus on signification, meaning, and discourse (apparent in media and

cultural studies) (13).

The affective turn in cultural theory has the benefit of recognizing that

sensations, moods, and feeling are a key part of cultural experience

alongside emotion, and that there are important somatic dimensions to

affect. (13)

o Some theorists posit affect as pre-personal intensity, whereas

emotion is something owned and recognized although

Hesmondhalgh is way of this (ask about this)

Has been work (Gabrielsson) on cataloguing strong emotional responses to

music but Hesmondhalgh suggests that this is perhaps a distorted

depiction of musical experience. Instead, everyday musical emotions

ted to be of low intensity rather than high, to be mostly unmemorable, and

to be short-lived and multiple rather than sustained. Furthermore, they

often involve negative emotions and prioritize basic rather than complex

emotions. What is more, many everyday musical experiences are hardly

aesthetic experiences at all, in the sense of experience oriented towards

beauty, pleasure, and other forms of reward from the perceptions of

artistic objects. (14)

As such, affective states in music must be examined outside the narrow

remit of aesthetic experience; and understanding of musical affect needs

to be related to questions of value and ethics.

Nussbaum suggests emotions have a narrative structure as such,

narrative artworks are valuable in that they help people to comprehend

their emotional narratives. (15)

Music has less palpable narrative structures than other forms of art such

as the novel, cinema or theatre.

This ambiguity means that music more than other arts is more suited to

precipitating introspection, and interacts with less tangible aspect of ones

emotional palette: its semiotic indefiniteness gives it a superior power to

engage with our emotions. (16)

Musics power to elicit these responses is not natural or pure culturally

constructed. experience of such emotions depends on familiarity with

the conventions that allow them, either through everyday contact with

musical idioms or through education. (16-17)

Nussbaum helps us see that one important way in which music matters is

that it can provide its own version of the ways that stories and plays

potentially enhance our lives, by cultivating and enriching our inner world

and by feeding processes of concern, sympathy, and engagement, against

helplessness and isolation. (17)

Flourishing not synonymous with happiness associated, but other

aspects to flourishing (loyalty, courage etc) and flourishing has

connotations of activity, whereas happiness merely connotes a state of

mind. (18)

Flourishing and wellbeing pluralist but not relativist.

Thus, quasi-objective understanding required: and appreciation that

fundamental human characteristics and needs are widely shared, though

they may take very different forms in different societies. (18)

Hesmondhalgh, using Nussbaums scheme of basic needs, suggests one

which is particularly relevant to music: being able to have attachments to

things and people outside ourselves; to love those who love and care for

us, to grieve at their absence; in general, to love, to grieve, to experience

longing, gratitude, and justified anger. Not having ones emotional

development blighted by fear and anxiety. (19)

Using Nussbaums earlier understanding of music as a valuable tool in the

comprehension and expression of emotions, a basic level of access to

music seems to be a requirement for flourishing.

Hesmondhalgh details further how music is fairly central to Nussbaums

theory of flourishing (see p 20)

Nussbaum overemphasizes high culture but her overall theory can be

applied to more popular forms as well. (21)

She tries to separate music as a specific force in inducing affect but in

reality, the experience of music is nearly always inseparable from [lyrics

etc] and other semiotic resources, and a consideration of the value of

music needs to understand that music takes many different forms in

modern societies, and that these different mediations interact in complex

ways. (22)

Music is always embedded within complex networks of meaning and

affect. (23)

o Popular song, with the centrality of lyrics, is therefore interesting as

it almost always embodies this complex network.

Hesmondhalgh suggests that tensions between liberation and repression,

obligation and freedom, suffering and enjoyment can all be found in Candi

Statons Young Hearts Run Free he suggests this is particularly

interesting as disco was a genre typically lambasted for its vacuous, and

hedonistic tendencies. (24)

Suggests that popular music without lyrics can still elicit complex

emotional responses (focusing on a jungle tune) the pleasure implied in

We are E (referencing MDMA; the energy of the tune) is juxtaposed with

its minor key, gunshot samples, its disorienting and frenetic composition.

A reflection of its urban and mixed setting hedonism but also confusion.

(26)

Nussbaums conception of music and its relationship with emotion and

flourishing could be interpreted as relying on the discredited concept of

culture and self-realization, a fundamentally naive and bourgeois idea

that conceives of individuals as oriented to self-realization, and thereby

excludes[s] most ordinary experiences of music. (26) Not sure where

Hesmondhalgh stands on this.

Hesmondhalgh points out that opportunities for emotional enrichment are

unevenly distributed (i.e. determined by social and economic position).

(27)

Is the very idea of a subject who develops herself through culture

compromised by its links to Western, bourgeois notions of selfhood and of

aesthetic canons? Might such a model as Nussbaums be guilty of

ethnocentrism and a submerged class politics? (27) This might be

useful

There have been leftist defenders of self-realization, too (Ryle and Soper)

who see self-realization through culture as having a potentially strong

social orientation, when it is combined with a more historical,

intersubjective and critically-honed sense of ones own identity and

society.

Ryle and Soper make a convincing case that the democratization of

cultural self-realization, especially through educational institutions, is not

only possible and coherent, but desirable, and that attacks on selfrealization based on excessive critique of subjectivity leave little ground

upon which to defend culture, or indeed the idea that people should live

their lives well. (28)

Ultimately though Nussbaum is reliant upon a contemplative individual

which Hesmondalgh suggests precludes engagement with other valuable

musical experiences that occur outside state of self-realization. (28)

Increasing amounts of study examine the more mundane uses people

make of music in everyday life which valuable moves discussion of

musics positive effects into the realm of mood and sensation. (28)

This work can be seen as complementary to Nussbaums combined, they

can serve to appreciate the somatic importance of musical affect as well

as the emotional (the dismissal of the embodied aspects of music has

generally characterized a great deal of musicology Hesmondhalgh

suggests that this might stem from the primacy that the mind has enjoyed

in aesthetics since Kant). (29)

Many people value music for the way it allows for aesthetic experiences

that combine bodily invigoration and emotional intensity. Paying proper

attention to this fact may take us more into the realm of the demotic, the

carnivalesque, the somatic, in ways that can complement Nussbaums

rather intellectualist focus on self-cultivation. (29)

Musical Aesthetics and Bodily Experience: Dancing

Compares dancing to flow centrality of a loss of self-consciousness, a

sensation of vitality, heightened physical awareness to the process,

sensual but deeply reflexive as well. This is often as much about order

and control as much as going wild. (31)

Dance is a form of play but it is also an aesthetic experience dance

provides musical experience of a bodily kind. (32)

Ask what the integrated subject means.

In line with American pragmatist philosophy, art (music+dance) is thus at

once instrumentally valuable and a satisfying end in itself. (33)

ASK ABOUT P 33

Art serves to heighten experience without precluding meaning and

reflection.

Some experiences invite an enjoyable and enriching lack of selfconsciousness (as in flow), while others have a puzzling quality which

invites us to reflect on what is valued. (33)

Hesmondhalgh suggests (but doesnt explain) that somatic aesthetic

experience is tied up with some of the most disturbingly instrumentalized

and commodified aspects of modern societies. (34)

***Suggests that aliveness as a quality is far from mystical and is instead

very ordinary and again hinges on a certain lack of self-consciousness

and/or the disappearance of otherwise often present existential fears and

questions (is my life worth living? etc) (34). Aivenes stems from being

with particular people, or doing something about which one is passionate

both of these can stem from music.

Difficulties can arise in this, however can preclude a degree of critical

thought necessary for aesthetic judgement in lieu of a mere socially

conditioned emotional response. (35)

Approaches to Music and Emotion in Everyday Life: Contributions and Limitations

For Adorno music could only contribute to bettering the world through

the coded language of suffering. (35)

A significant challenge for this book, then, is to produce a historically

informed, and critical, but non-Adornian, account of the relations

between music, power, subjectivity, and value, in the context of

ordinary experience of music. (35-6)

Hesmondhalgh considers music psychology which has, more than

aestheticians and philosophers, prioritised the quotidian interactions of

people with music.

However, he seeks to contextualise agency suggesting that for the

most part music psychologists underestimate the extent to which

social and psychological dynamics might limit peoples freedom to

act. (40)

Suggests good psychoanalyses still offer the most coherent accounts

of human subjectivity and its constraints, especially when combined

with insights drawn from philosophy and social science. (41)

Sloboda, DeNora and Finnegan (the 3 psycho-peeps that he refers to)

all risk downplaying various ways in which music may become

implicated in less pleasant and even disturbing features of modern life.

(41) THIS SECTION COULD BE USEFUL

Can music really be so autonomous that it floats free of social

forces? And, turning to self-identity, might not peoples

projects of self-creation (to use DeNoras term), and therefore

their uses of music as part of these projects, have some more

difficult and troubling dimensions than emerges in such

accounts? (41)

Hesmondhalgh seeks to provide a balanced critical account of the

place of the self in modern societies that shows how self-realization is

deeply compromised by certain conditions of capitalist modernity. This

allows us to build on the positive account of musical-aesthetic

experience based on emotion and human flourishing, by relating

aesthetic experience to historical developments in modern societies.

(42)

Post-60s, Capitalism has responded to what Boltanski and Chiapello

have termed the artistic critique of capitalism which stresses

capitalism as a sources of disenchantment and inauthenticity, and the

limits it places on freedom, autonomy, and creativity by providing

workplace situations that emphasise (and thus commodify) a form of

self-expression and individuality. This represents a form of commodified

flourishing where the self is an individual enterprise, and where

transitory relationships and commitments are considered more

legitimate than stable ones because rapidly changing ones

connections can supposedly lead to personal growth and greater selfrealization. (43)

Hesmondhalgh calls this a connexionist society.

This society -> increased depression, anomie, suicide etc.

In this context, the optimistic vision of self-realization via music put

forward by DeNora, Sloboda etc., is to some extent dubious.

Self-realization in a marketised sense also accommodates ideas about

hedonism. the tendency for leisure to be seen as a key means of

self-definition [does] not radically conflict with the needs of the

capitalist economy. Indeed these facets of modern societies have

become a productive force in their own right, in that they fuel cultural

consumption. (44)

This romantic idea of personal autonomy, which has been effectively

appropriated by capitalism, is not only largely impervious to musical

incursions it has also been constituted by music that has valorised it.

Jazz, hip-hop, soul and rock have all to some extent supported values

of rebellious creativity, but [have been] assimilated very quickly to

values of commercialism with unchallenging celebration of mobility

and unfettered individuality clearly bolstering the connexionism of

Boltanski and Chiapello. (45)

Difficulty comes from applying these historical metanarratives about

capital, culture, and music, to the everyday life that Hesmondhalgh is

interested in, without stripping individuals of any agency or autonomy.

See box 2.2 (46-8) for really interesting stuf about record collecting,

gender and music and emotion.

Competitive Individualism and Status Competition Through Music

Bourdieu singles out music from all other forms of culture in terms of

its power to act as a marker of class differentiation. (48)

Cas Wouters On status competition and emotion management

Decline of intrinsic status via birth or wealth (traditional means),

displays of the fact that one experiments with many lifestyles and an

awareness and knowledge of emotions have perhaps replaced

traditional markers of superiority music can be part of status battles

to show ones openness to a variety of lifestyle pleasures and ones

superior emotional range. After all, music has come to be linked,

perhaps more than any other cultural form, with the emotional

dimensions of ourselves. (49)

Equally, pressure to enjoy oneself publically and a certain duty to have

pleasure, the way modern individuals compete over who is having the

most fun, who is gaining most from life can be aided and underpinned

by musical experience.

o there are two ways in which music might be the basis of

status battles in modern society: in terms of the emotional

sensitivity of its consumers, and in terms of its basis for

hedonistic pleasures. (50)

PP 50 52 have personal examples of this.

Review

music can heighten peoples awareness of continuity and development in life.

It seems powerfully linked to memory, perhaps because it combines different

ways of remembering: the cognitive, the emotional, and the bodily sensory. (53)

READ THE REST OF IT

Вам также может понравиться

- Reuniting Acoustic and Electronic in Druckman's Synapse and ValentineДокумент4 страницыReuniting Acoustic and Electronic in Druckman's Synapse and ValentineClases de PianoОценок пока нет

- Bodies of Evidence, Singing Cyborgs and Other Gender Issues in Electrovocal MusicДокумент15 страницBodies of Evidence, Singing Cyborgs and Other Gender Issues in Electrovocal MusicltrandОценок пока нет

- "Blues For Pat": Acoustic BassДокумент2 страницы"Blues For Pat": Acoustic BassMichele BondesanОценок пока нет

- Chion: Voice in Cinema and The Muted CharacterДокумент2 страницыChion: Voice in Cinema and The Muted CharacterElpenor69Оценок пока нет

- Noise Music 101Документ59 страницNoise Music 101Lucy LoveОценок пока нет

- Noise Music As Queer ExpressionДокумент14 страницNoise Music As Queer ExpressionmotorcrashОценок пока нет

- Dancing about Architecture is a Reasonable Thing to Do: Writing about Music, Meaning, and the IneffableОт EverandDancing about Architecture is a Reasonable Thing to Do: Writing about Music, Meaning, and the IneffableОценок пока нет

- Existentialist Readings of Shakespeare SДокумент21 страницаExistentialist Readings of Shakespeare SSebastianОценок пока нет

- Great Reckonings in Little Rooms: On the Phenomenology of TheaterОт EverandGreat Reckonings in Little Rooms: On the Phenomenology of TheaterРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (8)

- Contemporary Drift: Genre, Historicism, and the Problem of the PresentОт EverandContemporary Drift: Genre, Historicism, and the Problem of the PresentОценок пока нет

- Roman SignerДокумент2 страницыRoman SignerAssaf GruberОценок пока нет

- Smoking in Bed: Conversations with Bruce RobinsonОт EverandSmoking in Bed: Conversations with Bruce RobinsonРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (10)

- Notes from the Road: A Filmmaker's Journey through American MusicОт EverandNotes from the Road: A Filmmaker's Journey through American MusicОценок пока нет

- M Butterfly - Orientalism - Gender and A Critique of Essentialist IdentityДокумент26 страницM Butterfly - Orientalism - Gender and A Critique of Essentialist IdentityStefania CovelliОценок пока нет

- David Hesmondhakgh, Keith Negus - Popular Music Studies (2002, Bloomsbury USA)Документ329 страницDavid Hesmondhakgh, Keith Negus - Popular Music Studies (2002, Bloomsbury USA)Guilherme MendesОценок пока нет

- Feminine EndingsДокумент4 страницыFeminine EndingsPyero TaloneОценок пока нет

- Adorno Radio SymphonyДокумент10 страницAdorno Radio SymphonyNazik AbdОценок пока нет

- Jerusalem in CanonДокумент3 страницыJerusalem in CanonSimon PayneОценок пока нет

- Landy - 1994 - The "Something To Hold On To Factor" in Timbral CompositionДокумент13 страницLandy - 1994 - The "Something To Hold On To Factor" in Timbral CompositionLina AlexakiОценок пока нет

- Postcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningОт EverandPostcolonial Repercussions: On Sound Ontologies and Decolonised ListeningJohannes Salim Ismaiel-WendtОценок пока нет

- Borgo Free Jazz in The ClassroomДокумент29 страницBorgo Free Jazz in The ClassroomJohn PetrucelliОценок пока нет

- An Analytic Storyteller - Kluge - Andreas HuyssenДокумент14 страницAn Analytic Storyteller - Kluge - Andreas HuyssenLenz21Оценок пока нет

- Brown - Phonography, Rock Records, and The Ontology of Recorded MusicДокумент13 страницBrown - Phonography, Rock Records, and The Ontology of Recorded MusicLaura Jordán100% (1)

- LivenessДокумент7 страницLivenessBrian TuohyОценок пока нет

- Electronic Sound (Issue 39 2018)Документ100 страницElectronic Sound (Issue 39 2018)Cristian Damián CochiaОценок пока нет

- Proportion, Temporality, and Performance Issues in Piano Works of John AdamsДокумент24 страницыProportion, Temporality, and Performance Issues in Piano Works of John AdamsCloudwalkОценок пока нет

- The Greek Music DramaДокумент20 страницThe Greek Music DramaJorge O El GeorgeОценок пока нет

- The Turin Horse: A Film by Béla TarrДокумент12 страницThe Turin Horse: A Film by Béla TarrRohith KumarОценок пока нет

- ONCE Festival GuideДокумент55 страницONCE Festival GuidesarabillОценок пока нет

- Only Lovers Left Alive - Vampire Love StoryДокумент7 страницOnly Lovers Left Alive - Vampire Love StoryTeodora CătălinaОценок пока нет

- Buchla 100er ManualДокумент119 страницBuchla 100er ManualCiijasavОценок пока нет

- Eliza Underminded The Romanticisation ofДокумент431 страницаEliza Underminded The Romanticisation ofppОценок пока нет

- Authorship and The Films of David Lynch - Aesthetic Receptions in Contemporary HollywoodДокумент191 страницаAuthorship and The Films of David Lynch - Aesthetic Receptions in Contemporary HollywoodSaeed Kakhki100% (1)

- Grass - "Fela Anikulapo-Kuti - The Art of An Afrobeat Rebel" - The Drama Review (1986)Документ19 страницGrass - "Fela Anikulapo-Kuti - The Art of An Afrobeat Rebel" - The Drama Review (1986)Sam CrawfordОценок пока нет

- Listening To Sound Art and Experimental MusicДокумент43 страницыListening To Sound Art and Experimental MusicShi-Lin HongОценок пока нет

- Plourde - Disciplined Listening in Tokyo: Onkyo and Non-Intentional SoundsДокумент27 страницPlourde - Disciplined Listening in Tokyo: Onkyo and Non-Intentional SoundsMatthew JenkinsОценок пока нет

- The Aesthetics of NoiseДокумент14 страницThe Aesthetics of NoiseMarcoInfantinoОценок пока нет

- Noys - Dance and Die - Obedience and Embedded Aesthetics of AccelerationДокумент8 страницNoys - Dance and Die - Obedience and Embedded Aesthetics of AccelerationradamirОценок пока нет

- Potaznik ThesisДокумент34 страницыPotaznik ThesisItzel YamiraОценок пока нет

- Martin Seel - Ethos of CinemaДокумент13 страницMartin Seel - Ethos of CinemaDavi LaraОценок пока нет

- Ramble City Postmodernism and Blade RunnerДокумент15 страницRamble City Postmodernism and Blade Runnermonja777Оценок пока нет

- TekufahДокумент1 страницаTekufahXam OnaznamОценок пока нет

- Wagner's Relevance For Today Adorno PDFДокумент29 страницWagner's Relevance For Today Adorno PDFmarcusОценок пока нет

- Soundtracks of Asian America by Grace WangДокумент38 страницSoundtracks of Asian America by Grace WangDuke University PressОценок пока нет

- Pfitzner v. Berg or Inspiration v. AnalysisДокумент3 страницыPfitzner v. Berg or Inspiration v. Analysiskvlt.bandОценок пока нет

- Laughter Over Tears: Water Walk by John CageДокумент8 страницLaughter Over Tears: Water Walk by John CageBrodie McCashОценок пока нет

- Ddmmyyyy Interview With Jennifer WalsheДокумент8 страницDdmmyyyy Interview With Jennifer WalsheRufus ElliotОценок пока нет

- 1996 - PL - Perception of Musical Tension in Short Chord Sequences - The Influence of Harmonic Function, Sensory Dissonance, Horizontal Motion, and Musical Training - Bigand, Parncutt and LerdahlДокумент17 страниц1996 - PL - Perception of Musical Tension in Short Chord Sequences - The Influence of Harmonic Function, Sensory Dissonance, Horizontal Motion, and Musical Training - Bigand, Parncutt and LerdahlFabio La Pietra100% (1)

- Composing With Shifting Sand - A Conversation Between Ron Kuivila and David Behrman On Electronic Music and The Ephemerality of TechnologyДокумент5 страницComposing With Shifting Sand - A Conversation Between Ron Kuivila and David Behrman On Electronic Music and The Ephemerality of TechnologyThomas PattesonОценок пока нет

- Mark Butler - Pet Shop BoysДокумент20 страницMark Butler - Pet Shop BoysCiarán DoyleОценок пока нет

- Allen Feldman - Strange FruitДокумент32 страницыAllen Feldman - Strange FruitAngelaОценок пока нет

- HANDKE, Peter. Kaspar - The Mechanics of Language - A FractionatingДокумент21 страницаHANDKE, Peter. Kaspar - The Mechanics of Language - A FractionatingJennifer JacominiОценок пока нет

- Brian Kane, MusicophobiaДокумент20 страницBrian Kane, MusicophobiakanebriОценок пока нет

- Gluck, Bob - The Nature and Practice of Soundscape CompositionДокумент52 страницыGluck, Bob - The Nature and Practice of Soundscape CompositionricardariasОценок пока нет

- Racial Science and Urban Conflict in Early 20th Century BarcelonaДокумент3 страницыRacial Science and Urban Conflict in Early 20th Century BarcelonaRichard ClareОценок пока нет

- Seminar 1 - Postmodernism NotesДокумент1 страницаSeminar 1 - Postmodernism NotesRichard ClareОценок пока нет

- David Malvinni - From Real Roma To Imaginary Gypsies NotesДокумент2 страницыDavid Malvinni - From Real Roma To Imaginary Gypsies NotesRichard ClareОценок пока нет

- Cities Essay 2 Preliminary NotesДокумент25 страницCities Essay 2 Preliminary NotesRichard ClareОценок пока нет

- Charles Tart - States of Consciousness PDFДокумент284 страницыCharles Tart - States of Consciousness PDFElianKitha100% (1)

- Interpersonal Forgiving in Close Relationships: Michael E. Mccullough Everett L. Worthington, JRДокумент16 страницInterpersonal Forgiving in Close Relationships: Michael E. Mccullough Everett L. Worthington, JRYulia AfresilОценок пока нет

- Apologies and love lettersДокумент11 страницApologies and love lettersOfficial Coolest kidОценок пока нет

- A Poison TreeДокумент2 страницыA Poison TreeNORITA AHMADОценок пока нет

- Reading Comprehension 1. Read The Following Passage and Choose The Best Answer To Each QuestionДокумент11 страницReading Comprehension 1. Read The Following Passage and Choose The Best Answer To Each QuestionLinh TranОценок пока нет

- Knyga6 MarkunasДокумент408 страницKnyga6 MarkunasRobertson FranceskoОценок пока нет

- Itai Ivtzan, Tim Lomas, Kate Hefferon, Piers Worth - Second Wave Positive Psychology - Embracing The Dark Side of Life (2015, Routledge)Документ4 страницыItai Ivtzan, Tim Lomas, Kate Hefferon, Piers Worth - Second Wave Positive Psychology - Embracing The Dark Side of Life (2015, Routledge)jssoufiaОценок пока нет

- Examples: Sympathy and Empathy in SentencesДокумент3 страницыExamples: Sympathy and Empathy in SentencesSvijayakanthan SelvarajОценок пока нет

- Using Customer Journey Maps To Improve Your Customer Experience 8-14-12Документ22 страницыUsing Customer Journey Maps To Improve Your Customer Experience 8-14-12Imelda Fauzi100% (2)

- Mentally Strong People Hold The PowerДокумент8 страницMentally Strong People Hold The PowerReaz ReazОценок пока нет

- The Role of Emotion in MarketingДокумент23 страницыThe Role of Emotion in MarketingSandy StancuОценок пока нет

- Aromatherapy questionnaire for emotional and physical well-beingДокумент1 страницаAromatherapy questionnaire for emotional and physical well-beingAgnesОценок пока нет

- 10-1108 - JPBM-12-2018-2150 #12Документ9 страниц10-1108 - JPBM-12-2018-2150 #12smart_kidzОценок пока нет

- The Causes of Suicidal Ideation in University StudentsДокумент5 страницThe Causes of Suicidal Ideation in University StudentszidkaОценок пока нет

- Psyc Essay Final 010420Документ2 страницыPsyc Essay Final 010420Ali HajassdolahОценок пока нет

- 20 Mindful Eating Handouts For Professionals Full Document Color PDFДокумент31 страница20 Mindful Eating Handouts For Professionals Full Document Color PDFPamela Aspbury Byrne100% (2)

- Analyzing Trust Issue Due To Infidelity: Lack of Commitment in The Dating RelationshipДокумент6 страницAnalyzing Trust Issue Due To Infidelity: Lack of Commitment in The Dating RelationshipghaisaniОценок пока нет

- Andrade (2005)Документ21 страницаAndrade (2005)vickycamilleriОценок пока нет

- CommunicationДокумент40 страницCommunicationLekshmi Manu100% (1)

- Schizophrenia Research: Claire I. Yee Tina Gupta, Vijay A. Mittal, Claudia M. HaaseДокумент7 страницSchizophrenia Research: Claire I. Yee Tina Gupta, Vijay A. Mittal, Claudia M. HaaseKhingZhevenОценок пока нет

- Stress-Free Pakistan ProjectДокумент11 страницStress-Free Pakistan ProjectSyed Irfan KamyabyОценок пока нет

- Personality, 9e: Jerry M. BurgerДокумент27 страницPersonality, 9e: Jerry M. BurgerChelle OcampoОценок пока нет

- Academic Stress Management StudyДокумент19 страницAcademic Stress Management StudyIris FayОценок пока нет

- JFSC E102Документ3 страницыJFSC E102osto72Оценок пока нет

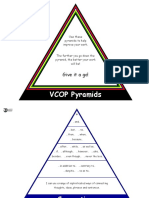

- VCOP Pyramids IndividualДокумент5 страницVCOP Pyramids IndividualmrbalintОценок пока нет

- Hamilton Rating Scale For Anxiety (HAM-A) : Questionnaire ReviewДокумент1 страницаHamilton Rating Scale For Anxiety (HAM-A) : Questionnaire ReviewIntanwatiОценок пока нет

- The 4 Types of IntrovertДокумент2 страницыThe 4 Types of IntrovertNadya Nadya100% (1)

- Completed Assignment 1Документ23 страницыCompleted Assignment 1api-3805016Оценок пока нет

- GE 001 UTS FinalДокумент15 страницGE 001 UTS FinalJocelyn Mae CabreraОценок пока нет

- How To Stop WorryingДокумент10 страницHow To Stop WorryingArjun Ajay PillaiОценок пока нет