Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Europe's Structural and Competitiveness Problems and The Euro

Загружено:

Beatriz Sartori BernabéОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Europe's Structural and Competitiveness Problems and The Euro

Загружено:

Beatriz Sartori BernabéАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Europes Structural and

Competitiveness Problems

and the Euro

Dominick Salvatore

1. INTRODUCTION

URING the first half of the 1980s, Europe was said to face eurosclerosis,

or low growth, high unemployment, and reduced international competitiveness. In 1986, however, the old continent seemed to reinvent itself by

deciding to move to a unified market by 1992. The Europe 92 programme

provided a stimulus to direct investments (both domestic and foreign) which led

to renewed growth in Europe in the second part of the 1980s. With the ushering of

the 1990s, however, Europe found itself in recession and again facing an

economic crisis. In this paper, I will examine the nature of this new crisis and the

contribution which the move toward the single currency (the Euro) may make

toward resolving or ameliorating it.

2. EUROPES RELATIVE GROWTH RATE

Table 1 shows the average growth of real GDP in the European Union (EU)

and in its major members (Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom)

during the decades of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s and compares these growth

rates to those of the United States, Japan, and the average for all industrial

(OECD) countries. The table shows that the average growth rate declined in all

countries and groups of countries during each decade (except for Germany during

the 19901996 period) but was consistently lower in the European Union than in

the United States, Japan, and the average for all OECD countries. During the

DOMINICK SALVATORE is Professor of Economics at Fordham University in New York. He

wishes to thank Ronald McKinnon, Robert Mundell, Michael Mussa and a Managing Editor for

helpful comments, but he alone is responsible for the content of the paper.

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998, 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK

and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

189

190

DOMINICK SALVATORE

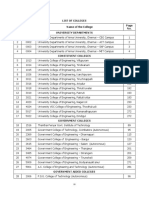

TABLE 1

Growth of Real GDP

(Average Annual Percentage Change)

OECD

United States

Japan

European Union

Germany

France

Italy

United Kingdom

19701979

19801989

19901996

19701996

3.7

3.5

4.6

3.2

2.9

3.5

3.6

2.4

2.8

2.8

3.8

2.2

1.8

2.3

2.4

2.4

1.9

1.9

2.3

1.7

2.6

1.4

1.2

1.2

2.9

2.8

3.7

2.4

2.4

2.5

2.5

2.1

Source: OECD, OECD Economic Outlook. (Paris: OECD, December 1996 and June 1997).

1970s, Italy and France grew as rapidly as the United States and did better than

Germany and the United Kingdom. During the 1980s Germany did much worse

than the other three major European Union countries, and all of them grew less

rapidly than the United States. The same is true for the 19901996 period, except

that Germany did better than the other large European Union members and grew

faster than the United States.

Over the entire 19701996 period, the United States grew at an average rate of

2.8 per cent per year as compared to the rate of 2.4 per cent per year for the

European Union. While the European Union rate is lower than the US rate, the

difference is not large. At a growth rate of 2.8 per cent per year, the US real GDP

would double in 26 years, while at a growth rate of 2.4 per cent per year the EUs

real GDP would double in 30 years. The difference between the US and the

European Union growth rate was also very similar in the most recent period (i.e.

19901996). Thus, the present crisis atmosphere in the European Union cannot be

due primarily to its inadequate growth rate because no such feeling of crisis exists

in the United States even though its average growth was only marginally higher

than that of the European Union (i.e. 1.9 per cent as compared to 1.7 per cent)

during the 1990s (Barro, 1997; Barro and Sala-I-Martin, 1995; Jorgenson, 1995;

Mankiw, 1995; and McCallum, 1996).

3. EUROPES RELATIVE INTERNATIONAL COMPETITIVENESS

One possible reason for Europes present crisis atmosphere is the widespread

belief that it is losing international competitiveness in high-technology products

with respect to the United States, Japan, and even some Asian developing

economies. Table 2 shows the changes in the international competitiveness in

high-technology products of the 12-member (15 in 1995) European Union with

respect to the United States, Japan, and Asia minus Japan, between 1980 and

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

191

TABLE 2

EU Trade in High-Technology Products

(billions of Dollars)

Region/Country and Year Exports

N. America

Japan

AsiaJapan

1980

1990

1995

1980

1990

1995

1980

1990

1995

18.40

49.39

72.12

1.86

10.25

16.13

13.12

33.29

80.38

Imports

Net balance

Net balance

as % of tot. manuf.

exports of EU

22.88

56.52

77.96

12.89

45.63

60.49

3.53

22.91

56.41

!4.48

!7.13

!5.84

!11.03

!35.38

!44.36

9.59

10.38

23.97

!1.69

!1.12

!0.36

!4.17

!5.54

!2.74

3.62

1.63

1.48

Source: GATT/WTO, International Trade (Geneva: GATT/WTO, 1996 and various earlier issues).

1995. Asia minus Japan refers primarily to the Dynamic Asian Economies

(DAEs), which include the four NIEs (Hong King, Korea, Taiwan and

Singapore), Malaysia, Thailand and China. High-technology goods refer here

to chemicals and drugs, power generating machinery, electrical machinery and

apparatus, non-electrical machinery, office and telecommunications equipment,

aircrafts and parts, automotive products, and other transport equipment.

Automotive products incorporate many new technologies and can increasingly

be regarded as high-technology products. Other transport equipment refers

primarily to locomotives. The table gives data on the high-technology exports and

imports, the net balance, and the net balance as a percentage of total

manufactured exports of the European Union with respect to North America,

Japan, and Asia minus Japan in 1980, 1990 and 1995.

Table 2 shows that in 1980 the European Union exported to North America

$18.40 billion of high-technology goods, imported $22.88 billion, for a net

balance of !$4.48 billion, which represented 1.69 per cent of the total exports of

all manufactured goods of the European Union. In 1990, EUs high-technology

exports to North America jumped to $49.39 billion, its imports increased to

$56.52 billion, for a net balance of !$7.13, which, however, represented only

1.12 per cent of the EUs total exports of manufactured goods. Thus, while the

EUs net balance in high-technology trade with North America worsened, it fell

as a percentage of its total manufactured exports, and so we could say that the

EUs international competitiveness position vis-a`-vis North America improved

between 1980 and 1990. This improvement continued after 1990 and by 1995 the

EUs negative net balance as a percentage of the EUs total exports of

manufactured goods had declined to !$5.84 billion, which represented only

(!)0.36 per cent of the EUs total manufactured exports.

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

192

DOMINICK SALVATORE

Thus, despite the widely-held belief to the contrary, the European Union did

not seem to have lost competitiveness with respect to the United States during the

first part of this decade. The belief that the European Union had become less

competitive vis-a`-vis the United States during the early 1990s was based on (1)

the elimination of the 1980s dollar overvaluation, (2) the much greater

computerisation of the American than the European economies, (3) the much

more extensive spread of computer-assisted design and computer-assisted

manufacturing in the US economy based on its unsurpassed superiority in

software, and (4) the much greater restructuring of the US economy than

European economies during the 1980s and early 1990s. It may be that the United

States is gaining competitively with respect to Europe, but the trade data up to

1995 does not seem to show it.

The European Union did lose in competitiveness with respect to Japan from 1980

to 1990, but since then it seems to have more than recaptured its lost ground. This

can be seen from the fact that the EUs net trade balance in high-technology

products with respect to Japan as a percentage of its total manufactured exports

worsened from !4.17 in 1980 to !5.54 in 1990, but then improved to !2.74 in 1995

(see Table 2). Only with respect to Asian economies other than Japan (mostly

DAEs), did the European Union lose in relative competitiveness continuously from

1980 to 1995. As shown in Table 2, the EUs positive trade balance in hightechnology goods with respect to Asian economies other than Japan as a per centage

of the EUs total manufactured exports declined from 3.62 in 1980 to 1.63 in 1990

and 1.48 in 1995. That is, the European Union still has a revealed comparative

advantage in high-technology goods with respect to the dynamic Asian economies

but it is shrinking (DAndrea Tyson, 1992; Hall and Jones, 1996; Krugman, 1994;

Porter, 1990; Rausch, 1995; and Salvatore, 1990 and 1997a).

4. EUROPES EMPLOYMENT PROBLEM

The major problem facing Europe today is its double-digit unemployment rate.

This is the result of inadequate growth of employment (Dreze and Malinvaud,

1994; Bean, 1994; Layard, Nickell and Jackman, 1994; Lindbeck, 1996; and

Phelps, 1994). Table 3 gives data on the average growth of employment in the

European Union during the decades of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s and compares

these average growth rates to those of the United States, Japan, and all industrial

(OECD) countries together. The table shows that the average growth of

employment in the European Union was less than one quarter that of the United

States and about one third that of Japan and all OECD countries between 1970

and 1989 and was in fact negative from 1990 to 1996. It is also not true that most

new jobs in the United States are low-paying jobs more than three-quarters of

them pay higher than average wages.

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

193

TABLE 3

Employment Growth

(Average Annual Percentage Change)

OECD

United States

Japan

European Union

19701979

19801989

19901996

1.4

2.6

1.2

0.4

1.1

1.7

1.1

0.4

0.7

1.1

0.8

!0.1

19701996

1.1

1.9

1.1

0.3

Source: OECD, OECD Economic Outlook (Paris: OECD, June 1997 and various earlier issues).

Even though the average growth of the labour force in the European Union was

less than one-half that of the United States over the 1970"1996 period, the average

growth of employment was less than one-quarter that of the United States, with the

result that the rate of unemployment increased sharply in the European Union but

remained the same, on average, in the United States between the first and the last

period under examination. Table 4 shows that the average rate of unemployment

between 1970 and 1979 was 3.8 per cent in the European Union as compared with

6.5 per cent in the United States, 1.7 per cent in Japan, and 4.6 per cent for all OECD

countries. For the 1980#1989 period, the corresponding rates (in percentages) were,

respectively, 8.9, 7.3, 2.5 and 7.1. For the most recent period (i.e. 1990#1996), the

average rate of unemployment was 10.2 per cent in the European Union as

compared with 6.3 per cent for the United States, 2.6 per cent for Japan, and 6.8 per

cent for all OECD countries (OECD, 1996b and 1997b).

Although the overall average rate of unemployment for the entire 19701996

period was very similar for the United States and the European Union, it was

much lower in the European Union than in the United States in the earliest period

(i.e. 19701979) and much higher in the most recent period (19901996). Indeed,

if we compared the unemployment rate in the year 1970 with that in 1996, we

find an even more startling difference. In 1970, the rate of unemployment was

about 2.5 per cent for the European Union as compared to 5.4 per cent for the

United States. In 1996, the rate of unemployment had more than quadrupled to

11.3 per cent in the European Union while it was the same at 5.4 per cent in the

TABLE 4

Unemployment Rates

(Average Annual Percentages)

OECD

United States

Japan

European Union

19701979

19801989

4.6

6.5

1.7

3.8

7.1

7.3

2.5

8.9

19901996

6.8

6.3

2.6

10.2

Source: OECD, OECD Economic Outlook (Paris: OECD, June 1997 and various earlier issues).

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

19701996

6.1

6.7

2.2

7.3

194

DOMINICK SALVATORE

United States. From being more than double the European unemployment rate in

1970, the US unemployment rate became less than half in 1996. What accounted

for this dramatic reversal?

5. CAUSES OF THE EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT PROBLEMS IN EUROPE

Until a few years ago if was fashionable to prescribe higher growth and more

investments to cure Europes employment and unemployment problems. That

these policies would not have been effective, however, should have been very

clear even then. As Table 1 showed, the average rate of growth of real GDP was

not much less in Europe than in the United States and yet the United States

created over 30 million jobs from 1970 to 1996 while the European Union only a

few millions. Of course, a much faster rate of growth would have created more

jobs in Europe, but inadequate growth was not the major cause of stagnant

employment in the European Union during the past quarter of a century. Nor was

the problem inadequate investments. In fact, as Table 5 shows, the European

Union invested a greater proportion of its GDP than the United States in every

time period, with average annual investments as a percentage of GDP equal to

20.7 per cent in the European Union, as compared with 19.1 per cent in the

United States over the entire 19701996 period. Thus, the cause of the European

employment and unemployment problems must be found elsewhere.

A closer look at the data reveals that investments in Europe were used

primarily to increase the capital-labour ratio (i.e. for capital deepening), which

increased labour productivity and real wages, while in the United States

investments were capital widening, which increased employment very much but

not labour productivity and wages. This can be seen in Tables 6 and 7. Table 6

shows that average labour productivity (defined as output per employed person)

grew much faster in the European Union than in the United States. It grew by 2.7

per cent in the European Union as compared with 0.4 per cent in the United States

TABLE 5

Gross Investments* as a Percentage of GDP

(Average Annual Percentages)

19751982#

OECD

United States

Japan

European Union

22.7

20.3

31.5

22.0

19831990

21.6

19.5

29.3

20.5

19911996

19751996

20.8

16.9

30.0

19.4

21.8

19.1

30.3

20.7

Notes:

* Include private and public, domestic and foreign.

# The different time breakdown than in previous tables is due to data availability.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook (Washington, DC: IMF, May 1997, p. 200).

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

195

TABLE 6

Growth of Labour Productivity

(Average Annual Percentage Changes)

OECD

United States

Japan

European Union

19731979#

19801989

19901995

19731995

1.9

0.4

2.8

2.7

1.7

1.0

2.6

1.8

1.2

0.5

1.5

2.1

1.6

0.7

2.3

2.1

Note:

# The different time breakdown is due to data availability.

Source: OECD, OECD Economic Outlook (Paris: OECD, December 1996, pp. 19 and A68).

TABLE 7

Growth of Real Labour Compensation

(Average Annual Percentage Changes)

19701979

OECD

United States

Japan

European Union

2.3

1.0

4.7

3.4

19801989

!0.3

0.3

1.3

5.3

19901996

19701996

!0.6

0.4

0.9

2.2

0.6

0.6

2.6

4.2

Source: OECD, OECD Economic Outlook (Paris: OECD, December 1996, pp. A15 and A18).

from 1973 to 1979, 1.8 per cent as compared with 1.0 per cent during 19801989,

and 2.1 per cent as compared with 0.5 per cent during 19901996, for an overall

annual average growth over the 19731995 period of 2.1 per cent in the European

Union as compared with 0.7 per cent in the United States.

Table 7 shows that this much greater increase in labour productivity in the

European Union than in the United States resulted in much higher increases in

real wages in the European Union than in the United States in each time period

and for the entire 19701996 time period. Thus, new investments in the European

Union were used primarily for capital deepening and these raised labour

productivity and real wages but created very few new jobs. By contrast, most

investments in the United States were capital widening, which created many new

jobs without, however, increasing labour productivity and real wages very much.

The crucial question is why?

6. EUROPES INFLEXIBLE LABOUR MARKETS

The major reason for the slow growth of employment and rapid rise in

unemployment in the European Union as compared with the United States is the

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

196

DOMINICK SALVATORE

inflexibility of labour markets in the former. The European Union has a social

welfare system and worker protection which makes labour not only very costly

but also makes labour markets rather inflexible. Once hired, it is practically

impossible for a European firm to fire a worker even when the firm no longer

needs the worker. But if firms cannot fire workers easily when their demand for

labour declines, they are much less likely to hire new workers when firms

demand for labour increases.

In many EU countries, more than 50 per cent of the labour force is unionised,

as compared with less than 15 per cent in the United States, and labour unions are

notoriously more interested in protecting the jobs of union members and

bargaining for high wages for their members than with creating new jobs (see

Salvatore, 1996). EU countries also provide much more generous social security

benefits to unemployed workers than the United States and this discourages

workers from finding jobs. For example, while unemployment benefits are about

50 per cent of wages in the United States and are provided for only 26 weeks, in

the European Union they exceed 75 per cent of wages and are often provided for

as long as three years (and sometimes even longer). It has been found (Economic

Report of the President of the United States, 1993, p. 107) that each additional

week of unemployment benefits will increase the expected duration of

unemployment in the United States by about half a week and that the longer

the benefit period the less is the likelihood that unemployed workers will shift to

other industries. Katz and Meyer (1990) found that the probability of finding a

job doubled when unemployment benefits ran out.

The most disturbing feature of the high overall and long-term unemployment

rates in EU countries is the slow adjustment toward a long-run equilibrium in

EUs labour markets since the early 1970s. This is clearly apparent from the

tendency for the unemployment rate, after rising during a cyclical downturn, to

decline only slowly when economic activity picks up again and never returning to

its previous lower level. This occurred after all the four recessions that the EU

countries faced over the past quarter of a century. In other words, EU

unemployment rates seem to fluctuate during the course of successive business

cycles along a rising time trend. This suggests that while there are many causes of

rising unemployment in EU countries, unemployment persistence and slow

labour market adjustment can best be regarded as the result of labour market

inflexibility.

Slow labour market adjustment also means that the response of EU countries to

the strong movement toward the globalisation of economic activities that has

been taking place in the world economy as a result of the revolution in

telecommunications did not create many new jobs in the European Union.

Globalisation creates many opportunities for new jobs in expanding sectors, but

somehow EU countries were unable to take full advantage of these new

opportunities. With labour markets and real wages more much flexible than in the

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

197

European Union, the United States has been able to adjust much more rapidly and

effectively to these momentous changes in the world economy and succeeded in

creating millions of new jobs during the past two decades. Higher European

unemployment can also not be attributed to the pace of technological change,

since that has occurred even more rapidly in the United States (and, in any event,

there is no reason to believe that technological change necessarily destroys more

jobs than it creates). What technological change did do is destroy unskilled jobs

while creating skilled jobs. It is only by possibly increasing the mismatch

between labour demand and labour supply in various skills that technological

change can be said to be related to higher unemployment. But this has occurred in

both Europe and the United States and does not explain the much higher longterm unemployment rate in the former than in the latter. In any event, the solution

to the unemployment problem is not to slow down the pace of technological

change, but rather to increase job training and labour mobility to fill the new high

skilled jobs being created.

7.POLICIES TO OVERCOME EUROPES EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT

PROBLEMS

The 1994 and 1995 OECD Job Study classifies policies to reduce unemployment into two broad categories: those that involve the removal of existing

impediments to hiring and those that actively seek to improve the operation of

labour markets and encourage hiring. Among the first type of policies are the

reduction in the amount and duration of unemployment benefits (which, as we

have seen discourage workers from seeking jobs), lowering non-wage labour

costs such as employers social security contributions, reducing real minimum

wages (by keeping nominal minimum wages constant in the face of some price

inflation), remove or weaken the automatic indexation of wages to prices, relax

firms anti-firing rules, remove the restrictions imposed by unions and

professional associations on entry in certain occupations, and allow temporary

work arrangements. Most European countries have already begun to adopt some

of these policies, but much more needs to be done. The United Kingdom and the

Netherlands are two EU members that succeeded in increasing labour market

flexibility and have much lower unemployment rates than the rest (McKinsey

Global Institute, 1997; and OECD, 1996a).

The OECD also advocates active labour market policies (ALMPs) to provide

job training and skills, job-search assistance and counselling, and subsidies to

help long-term unemployed workers pay the cost of relocating to areas where

jobs are available and thus help them become fruitfully employed. In fact, nations

should shift more of their resources from passive labour policies (such as

unemployment benefits) to ALMPs. While in the short term there is no substitute

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

198

DOMINICK SALVATORE

for flexible wages, in the long term providing job training and skills are most

important (CEPR, 1995).

No country has gone further in adopting and implementing these ALMPs than

Sweden, whose relatively low rate of unemployment, despite the highest rate of

labour force unionisation in OECD countries, demonstrates that these

programmes can be effective if they are carefully targeted and monitored and

if they are undertaken on a large scale (Calmfors and Skendinger, 1995; and

Scarpetta, 1996). Although most other European countries have started some new

such programmes in recent years, they are generally not on a sufficiently large

scale to have a major overall impact in enhancing the employment prospects of

long-term unemployed unskilled workers, even if successful. In the final analysis,

reducing the rate of unemployment in Europe is to a large extent a political

decision on how much those who hold jobs are willing to sacrifice (in the form of

reduced job security and above equilibrium wages) for the sake of increasing

employment of long-term unemployed workers.

Many policies that are sometimes advocated to reduce the unemployment

problem now facing most OECD countries would simply not work. Reducing

technological progress would only reduce the growth of standards of living in the

long run without increasing employment much, if at all, even in the short run.

Restricting exports from the newly industrialising countries would also not have

much effect on employment in OECD countries because these exports represent

less than 2 per cent of the goods and services consumed by OECD countries.

Such trade restrictions would only interfere with international specialisation,

efficiency, and growth in developed and developing countries alike (Salvatore,

1993 and 1996a). The same is true of policies to protect the nation from the

globalisation of economic activity that is taking place in the world economy

today. Trying to reduce the length of the work week in order to share work

without at the same time proportionately reducing salaries would only increase

labour costs and reduce employment. Encouraging early retirement would also

tend to make the nation poorer. The secret is to find fruitful employment for all

those who are willing and able to work rather than reducing the size of the labour

force in a vane attempt to reduce unemployment.

8. THE EURO AND EUROPES EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT PROBLEMS

The general benefits from the establishment of the euro are well known and

include: (1) the elimination of the need to exchange currencies of EU members

(this has been estimated to save as much as $30 billion per year); (2) the

elimination of excessive volatility among EU currencies (fluctuations will only

occur between the euro and the dollar, the yen, and the currencies of non-EU

nations); (3) more rapid economic and financial integration among EU members;

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

199

(4) a European Central Bank which may conduct a more expansionary monetary

policy than the generally more restrictive one now practically imposed on other

EU members by the Bundesbank; and finally (5) greater economic discipline for

countries, such as Italy and Greece, that seem unwilling or unable to bring their

house in order without externally-imposed conditions. But will the movement and

actual establishment of the euro in January 1999 help resolve or at least

ameliorate the serious employment and unemployment problems now widespread

in the European Union?

A single market with one currency will certainly make the EU countries more

competitive globally in the long run and this will certainly be good for

employment.1 The effort currently under way to meet the Maastricht criteria is

only forcing EU member nations to restructure their economies more quickly or

at least making them more painfully aware of the need to do so. EU nations now

understand the need to change their pension and welfare systems, slash budgets,

reduce subsidies, and privatise the economy with a view towards containing

labour costs and increasing labour market flexibility. The prospect of much

greater competition when the euro arrives is also inducing companies to cut costs

and, whenever possible, jobs, and payrolls so as to become more internationally

competitive.

But it is the globalisation process now proceeding rapidly as a result of the

revolution in telecommunications and transportation that is requiring nations and

companies throughout the world to restructure so as to meet the global

competitiveness challenge. The Maastricht Treaty and the movement towards the

euro is only making EU member nations more aware of the need to restructure

their economies and speeding such a process on a coordinated EU-wide scale. It

is now becoming painfully clear that the enviable social welfare system that EU

members have so painstakingly put together since the end of World War II (and

of which they are justifiably very proud) is no longer sustainable in the present

form in a world of global competition. Benefits such as job security rules, high

unemployment pay, paid medical care, and early retirement are hard-won

achievements that EU labour is not going to give up easily.

It is global competition and not the coming of the euro, however, that is

creating the need to restructure and increase efficiency for all nations and

companies throughout the world. What the Maastricht Treaty and the

movement towards the euro is doing is to stimulate the process by making

EU members face up to the need to restructure and actually introduce the

required changes. It is true that for nations to slash budgets to meet the

Maastricht criteria and for companies to restructure and shed labour at a time

when most EU member nations face huge unemployment is very painful. But

these changes are necessary if Europe is to be fully part of and to adequately

1

Not everyone agrees with this. See, for example, Greenaway (1995).

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

200

DOMINICK SALVATORE

benefit from the dynamic globalisation process now in progress. The very fact

that labour is now rebelling (e.g. the results of the recent French election)

against the drastic changes and restructuring required is proof that without the

Maastricht Treaty and the move toward the euro, European countries would be

much more reluctant and much less willing to introduce the drastic changes

that increased globalisation and world competition require.

If Europe fails to face up to the challenge it risks falling behind in the global

competitiveness race and becoming a backwater to the United States, Japan, and

even some of the larger and more dynamic Asian economies (DAEs). The United

States went through such a painful restructuring during the 1980s and is now the

most competitive nation in the world (see World Economic Forum, 1997). While

Japan faces many similar restructuring problems to Europe, it remains the second

most competitive nation in the world among the G-7 countries, and is well ahead

of Europe. Even the DAEs are moving up very rapidly. Thus, it is crucial for

Europe to rise up to the challenge and not delay the required restructuring. This

does not necessarily mean dismantling its entire social welfare system or

switching completely to a more liberal or market-oriented model of the AngloSaxon type, but to the realisation that any social welfare benefit over and above

those received by people and workers in the United States and Japan, but also in

the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, is expensive in terms of government

finances and international competitiveness. The danger now is that labour

rebellion against social welfare cuts and revising the common postwar social

contract will force governments to delay and will water down the restructuring

process.

9. ASYMMETRIC SHOCKS AND THE EURO

One serious unresolved problem that the establishment of a European Central

Bank (ECB) and the euro may create is how an EU member will respond to an

asymmetric shock. It is practically inevitable that a large and diverse single

currency area such as the European Union will face periodic asymmetric shocks

that will affect various member nations differently and drive their economies out

of alignment. In such a case, there is practically nothing that a nation so adversely

affected can do. It is clear that the nation cannot change the exchange rate or use

monetary policy to overcome its problem because of the existence of a single

currency, and fiscal discipline will also prevent it from using this policy to deal

with the problem (Baldassarri, Imbriani and Salvatore, 1996; Fratianni and

Salvatore, 1993; and Fratianni, Salvatore and von Hagen, 1997).

A single currency works well in the United States because if a region suffers an

asymmetric shock, workers move quickly and in great numbers out of the region

adversely affected by the shock and towards areas of greater employment

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

201

opportunities. In fact, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and

Development (1986) and the European Commission (1990) found that labour

mobility among EU members is from two to three times lower than among US

regions. In addition, in the United States there is a great deal of federal fiscal

redistribution in favour of the adversely affected region. In the European Union,

on the other hand, fiscal redistribution cannot be of much help because the EU

budget is only about one per cent of the EUs GDP and more than half of it is

devoted to its Common Agricultural Policy (Salvatore, 1997b). Furthermore, real

wages are also somewhat more flexible downward in the United States than in the

European Union. It should be clear that none of these escape valves are available

to an EU member adversely affected by a negative asymmetric shock. Otherwise,

how could we account for the persistence of much higher unemployment rates

among EU nations and regions than among US regions?

Facing such a predicament, the United Kingdom and Italy opted for leaving the

Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) of the European Monetary System (EMS) in

September 1992 and, by allowing their currencies to depreciate, were able to

move out of the deep recession in which they found themselves. With a single

currency this would have been impossible. Remaining in the ERM of the EMS in

September 1992 would have meant Britain and Italy standing idly by and

watching their unemployment rate increase from already very high levels until

the recession came to an end naturally and gradually over time. No government

can afford to do this. In any event, massive speculation against the pound and the

lira forced a depreciation of those currencies. It is true that the establishment of a

single currency will prevent such speculative attacks. But that also means that

with a single currency the nation will have no policy choice available. It will

simply have to wait out for the recession to be cured by itself (see Salvatore,

1996b).

Supporters reply that the requirements for the establishment of single currency

will necessarily increase labour market flexibility and, by promoting greater

intra-EU trade, a single currency will also dampen nationally differentiated

business cycles. Furthermore, it is pointed out that highly integrated EU capital

markets can make up for low labour market flexibility and provide the automatic

response to asymmetric shocks in the European Union. While these automatic

responses to asymmetric shocks may in fact be present, they may not be adequate.

It is true that meeting the Maastricht parameters will increase labour market

flexibility. But this may be a slow process and may not be allowed to take place

to a sufficient degree if EU labour insists on retaining many of its present benefits

(such as job security and high unemployment pay). Furthermore, excessive

capital flows may also work perversely by reducing the incentive for fundamental

adjustment measures and may even produce supply shocks of their own by

pushing up the exchange rate of the EU member adversely affected by an

asymmetric shock.

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

202

DOMINICK SALVATORE

10. PERIPHERAL AREAS AND THE EURO

The move to the euro is also likely to create serious problems for peripheral

EU regions and nations. That is, the greater economic and financial integration

that the move toward the euro will entail and encourage is likely to increase the

geographical concentration of economic activities at the core of the EU area and

lead to increased economic inequalities between the centre and the periphery.

Southern Italy, Scotland, Northern Sweden, and even entire peripheral countries,

such as Greece and Portugal, are likely to become poorer as a result of a process

of cumulative causation so aptly discussed by Gunnar Myrdal in 1957. That is,

peripheral areas and countries are likely to lose their best trained people who

might be attracted by the higher salaries and the better career opportunities in EU

core areas. Similarly, the savings of the peripheral areas may flow to and be

invested in the EU core regions, attracted by the smaller risks and the likely

higher returns there. Finally, it is difficult for industries in peripheral areas to

effectively compete with EU-core industries.

Such progressive impoverishment of peripheral areas is evident within many

EU member nations, but the process is likely to gain steam as the European

Union moves toward a truly integrated economy. The experience with prior

economic integration at the national level of many EU member nations clearly

points in that direction. And EU regional policies to help peripheral areas are not

likely to be sufficient to reverse the trend toward greater interregional inequality.

For example, after 50 years of a massive effort by the national government to

help the Italian South, the gap in real per capita income of the Mezzogiorno

relative to the North is as wide, if not wider today, as it was in 1950. Despite

accusations of waste, the Italian government tried almost everything imaginable

to help the South narrow differences with the more industrialised North. It tried a

land reform, it built infrastructures, it built massive industries such as the steel

industry at Taranto, it tried incentives to small firms, and introduced programmes

to train labour all seemingly to no avail.

It is wrong, however, to infer from this that the special effort to help the South

was entirely ineffective. The effectiveness of such a programme can only be

measured by counterfactual simulation. That is, what would the North-South

difference have been without the massive effort to help the South? Unless the

programme was a complete waste, the North-South difference would have been

greater without the governments programme to help the South. The point is that

the unhampered operation of the market mechanism can be expected to increase

peripheral-centre inequalities and even a massive government effort to reverse

this trend may not be sufficient to prevent regional inequalities from increasing.

Despite an even more massive and concentrated effort by Germany to help the

Eastern portion of the country restructure its economy after decades of

communism, West-East differences remain very large today. And peripheral

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

203

regions can certainly not expect the same degree of effort from the EU Regional

Development Fund. Thus, the move towards the euro is likely to lead to even

greater concentration of economic wealth at the EU core and result in widening

inequalities of peripheral areas.

11. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The European Union grew only slightly less than the United States during the

19701996 period. Trade data also shows that while the EUs competitiveness in

high-technology goods worsened with respect to Japan from 1980 to 1990 and

with respect to Asian countries other than Japan from 1980 to 1995, it did not

with respect to the United States from 1980 to 1995, and especially since 1990.

To be sure, the European Union still has a large trade deficit in high-technology

goods with respect to the United States, but as a percentage of its total manufactured exports, the EUs position has improved significantly since 1990. The

major economic problem facing the European Union today is that so few new

jobs are being created. This resulted in a big increase in the unemployment rate,

despite the fact that the EU labour force grew very slowly during the past quarter

of the century.

The EUs employment and unemployment problem was not due to inadequate

growth of real GDP and investments but resulted because most investments were

capital deepening and increased the capital-labour ratio, labour productivity, and

real wages without creating many new jobs, while they were capital-widening

and sharply increased employment in the United States without, however,

increasing wages very much. The reason for this sharp difference is to be found in

the EUs inflexible labour markets. The OECD correctly advocates both policies

to remove impediments to work (such as reducing unemployment benefits and

minimum wages) and active labour market policies (ALMPs) to provide job

training and skills for long-term unskilled unemployed workers to help them

become fruitfully employed. Most European nations have adopted some of these

policies but much more needs to be done.

A single market with one currency will certainly make the EU countries more

competitive globally in the long run and this will certainly be good for

employment. But it is the globalisation revolution that is requiring nations and

companies throughout the world to restructure in order to meet the global

competitiveness challenge. The Maastricht Treaty and the movement towards the

euro is only making EU member nations more painfully aware of the need to

restructure their economies and to speed such a process on a coordinated EUwide basis. To that extent, the move toward the euro will stimulate EU

competitiveness and shorten the time before the restructuring process will lead to

significant new job creation. The creation of a European Central Bank and move

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

204

DOMINICK SALVATORE

towards the euro will, however, result in significantly greater adjustment costs for

EU members affected by asymmetric shocks and will exacerbate the economic

problems of peripheral EU nations and regions and increase their inequalities

with EU core areas.

REFERENCES

Baldassarri, M., C. Imbriani and D. Salvatore (eds.) (1996), The International System Between New

Integration and Neo-Protectionism (London: Macmillan).

Barro, R.J. (1997), Determinants of Economic Growth (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press).

Barro, R.J. and X. Sala-I-Martin (1995), Economic Growth (New York:McGraw-Hill).

Bean, C.R. (1994), European Unemployment: A Survey, Journal of Economic Literature, 32,

573619.

Calmfors, L. and P. Skendinger (1995), Does Active Labour Market Policy Increase Employment?

Theoretical Considerations and Some Empirical Evidence from Sweden, Seminar Paper No.

590 (Stockholm: Institute for International Economic Studies, March), pp. 140.

CEPR (1995), Unemployment: Choices for Europe (London: Centre for Economic Policy

Research).

DAndrea Tyson, L. (1992), Whose Bashing Whom? Trade Conflict in High-Technology Industries

(Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics).

Dreze, J.H. and E. Malinvaud (1994), Growth and Employment: The Scope of a European

Initiative, European Economic Review, 4, 489504.

Economic Report of the President (1993, 1997), Council of Economic Advisors (Washington, DC:

US Government Printing Office).

European Commission (1990), One Market, One Money, European Economy, 44, Brussels:

Commission for the European Communities.

Fratianni, M. and D. Salvatore (eds.) (1993), Monetary Policy in Developed Countries (Amsterdam:

North-Holland).

Fratianni, M., D. Salvatore and J. von Hagen (eds.) (1997), Macroeconomic Policies in Open

Economies (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press).

GATT/WTO (1996), International Trade (Geneva: GATT/WTO, 1996 and earlier issues).

Greenaway, D. (1995), EU + ERM "# EMU: So Why Have a Single Currency in Europe?, Esmee

Fairbairn Memorial Lecture, Lancaster University.

Hall, R.E. and C.I. Jones (1996), The Productivity of Nations, Working Paper 5812 (Cambridge,

Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, November).

IMF (1997), World Economic Outlook (Washington, DC: IMF, May).

Jorgenson, D.W. (1995), Postwar U.S. Economic Growth (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press).

Katz, L.F. and B.D. Meyer (1990), Unemployment Insurance, Recall Expectations, and

Unemployment Outcomes, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 9731002.

Krugman, P. (1994), Competitiveness: A Dangerous Obsession, Foreign Affairs, 73, 2844.

Layard R., S. Nickell and R. Jackman (1994), The Unemployment Crisis (New York: Oxford

University Press).

Lindbeck, A. (1996), The West European Employment Problem, Seminar Paper No. 616

(Stockholm: Institute for International Economics, Stockholm University, November).

McCallum, B.T. (1996), Neoclassical vs. Endogenous Growth Analysis: An Overview, Working

Paper 5844 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, November).

McKinsey Global Institute (1997), Removing Barriers to Growth and Employment in France and

Germany (Washington DC: McKinsey Global Institute).

Mankiw, G.N. (1995), The Growth of Nations, Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 275

326.

Myrdal, G. (1957), Rich Lands and Poor (New York: Harper & Row).

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

EUROPES PROBLEMS AND THE EURO

205

OECD (1986), Flexibility in the Labor Market (Paris: OECD).

OECD (1994), The OECD Job Study: Facts Analysis, Strategies (Paris: OECD).

OECD (1995), The OECD Job Study: Implementing the Strategy (Paris: OECD).

OECD (1996a), Employment Outlook (Paris: OECD).

OECD (1996b), Labor Force Statistics: 19731994 (Paris: OECD).

OECD (1997a) OECD Economic Outlook (Paris: OECD, December and June).

OECD (1997b), Employment Outlook (Paris: OECD).

Phelps, E.S. (1994), Structural Slumps: The Modern Equilibrium Theory of Unemployment,

Interest, and Assets (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press).

Porter, M. (1990), The Comparative Advantage of Nations (New York: Free Press).

Rausch, L.M. (1995), Asias New High-Tech Competitors (Washington, DC: National Science

Foundation).

Salvatore, D. (1990), The Japanese Trade Challenge and the U.S. Response (Washington, DC:

Economic Policy Institute).

Salvatore, D. (ed.) (1993), Protectionism and World Welfare (New York: Cambridge University

Press).

Salvatore, D. (1996a), The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), International

Thompson Publishing, International Encyclopedia of Business and Management, 15941600.

Salvatore, D. (1996b), The European Monetary System: Crisis and Future, Open Economies

Review, 7, 593615.

Salvatore, D. (1997a), Globalization and International Competitiveness, in J. Dunning (ed.)

International Competitiveness (New York: Pergamon Press, forthcoming).

Salvatore, D. (1997b), The Unresolved Problem with the EMS and EMU, American Economic

Review, 87, 224226.

Scarpetta, S. (1996), Assessing the Role of Labor Market Policies and Institutional Settings on

Unemployment: A Cross-Country Study, OECD Economic Studies, 26, 4498.

World Economic Forum (1997), The Global Competitiveness Report (Geneva: World Economic

Forum).

! Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1998

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Food Combining PDFДокумент16 страницFood Combining PDFJudas FK TadeoОценок пока нет

- Holophane Denver Elite Bollard - Spec Sheet - AUG2022Документ3 страницыHolophane Denver Elite Bollard - Spec Sheet - AUG2022anamarieОценок пока нет

- FAMILYДокумент3 страницыFAMILYJenecel ZanoriaОценок пока нет

- Weird Tales v14 n03 1929Документ148 страницWeird Tales v14 n03 1929HenryOlivr50% (2)

- Assignment File - Group PresentationДокумент13 страницAssignment File - Group PresentationSAI NARASIMHULUОценок пока нет

- For FDPB Posting-RizalДокумент12 страницFor FDPB Posting-RizalMarieta AlejoОценок пока нет

- Brahm Dutt v. UoiДокумент3 страницыBrahm Dutt v. Uoiswati mohapatraОценок пока нет

- Newspaper OrganisationДокумент20 страницNewspaper OrganisationKcite91100% (5)

- PropertycasesforfinalsДокумент40 страницPropertycasesforfinalsRyan Christian LuposОценок пока нет

- Academic Decathlon FlyerДокумент3 страницыAcademic Decathlon FlyerNjeri GachОценок пока нет

- IIT JEE Physics Preparation BooksДокумент3 страницыIIT JEE Physics Preparation Booksgaurav2011999Оценок пока нет

- Management of Graves Disease 2015 JAMA AДокумент11 страницManagement of Graves Disease 2015 JAMA AMade ChandraОценок пока нет

- Georgia Jean Weckler 070217Документ223 страницыGeorgia Jean Weckler 070217api-290747380Оценок пока нет

- 44) Year 4 Preposition of TimeДокумент1 страница44) Year 4 Preposition of TimeMUHAMMAD NAIM BIN RAMLI KPM-GuruОценок пока нет

- 059 Night of The Werewolf PDFДокумент172 страницы059 Night of The Werewolf PDFomar omar100% (1)

- Reflecting Our Emotions Through Art: Exaggeration or RealityДокумент2 страницыReflecting Our Emotions Through Art: Exaggeration or Realityhz202301297Оценок пока нет

- The Rise of Political Fact CheckingДокумент17 страницThe Rise of Political Fact CheckingGlennKesslerWPОценок пока нет

- Picc Lite ManualДокумент366 страницPicc Lite Manualtanny_03Оценок пока нет

- TNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Документ18 страницTNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Ajith KumarОценок пока нет

- Human Development IndexДокумент17 страницHuman Development IndexriyaОценок пока нет

- Improving Downstream Processes To Recover Tartaric AcidДокумент10 страницImproving Downstream Processes To Recover Tartaric AcidFabio CastellanosОценок пока нет

- 5f Time of Legends Joan of Arc RulebookДокумент36 страниц5f Time of Legends Joan of Arc Rulebookpierre borget100% (1)

- Bodhisattva and Sunyata - in The Early and Developed Buddhist Traditions - Gioi HuongДокумент512 страницBodhisattva and Sunyata - in The Early and Developed Buddhist Traditions - Gioi Huong101176100% (1)

- Full Download Test Bank For Health Psychology Well Being in A Diverse World 4th by Gurung PDF Full ChapterДокумент36 страницFull Download Test Bank For Health Psychology Well Being in A Diverse World 4th by Gurung PDF Full Chapterbiscuitunwist20bsg4100% (18)

- Positive Accounting TheoryДокумент47 страницPositive Accounting TheoryAshraf Uz ZamanОценок пока нет

- Fix List For IBM WebSphere Application Server V8Документ8 страницFix List For IBM WebSphere Application Server V8animesh sutradharОценок пока нет

- Executive SummaryДокумент3 страницыExecutive SummarySofia ArissaОценок пока нет

- Https Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintДокумент59 страницHttps Emedicine - Medscape.com Article 1831191-PrintNoviatiPrayangsariОценок пока нет

- 5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийДокумент13 страниц5g-core-guide-building-a-new-world Переход от лте к 5г английскийmashaОценок пока нет

- AI in HealthДокумент105 страницAI in HealthxenoachОценок пока нет