Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Shelter That Wasn T There On The Pol

Загружено:

Nico SanhuezaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Shelter That Wasn T There On The Pol

Загружено:

Nico SanhuezaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Urban

Studies

http://usj.sagepub.com/

The Shelter that Wasn't There: On the Politics of Co-ordinating Multiple Urban

Assemblages in Santiago, Chile

Sebastian Ureta

Urban Stud 2014 51: 231 originally published online 3 June 2013

DOI: 10.1177/0042098013489747

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://usj.sagepub.com/content/51/2/231

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Urban Studies Journal Foundation

Additional services and information for Urban Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://usj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://usj.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Dec 23, 2013

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Jun 3, 2013

What is This?

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

51(2) 231246, February 2014

Article

The Shelter that Wasnt There: On the

Politics of Co-ordinating Multiple Urban

Assemblages in Santiago, Chile

Sebastian Ureta

[Paper first received, April 2012; in final form, October 2012]

Abstract

The concept of assemblages has gained an important degree of momentum in urban

studies claiming to offer a new ontology for understanding cities as emergent and

fluid concatenations of multiple elements. Such a conception, however, has also

been criticised in relation to its supposed failure to deal effectively with the issue of

power and inequality in urban dynamics. This paper contributes to this on-going

discussion by exploring in detail the way in which power was embedded in one particular case: a bus stop shelter located in front of the Biblioteca Nacional in

Santiago, Chile. In so doing, it analyses the controversy arising when two large and

complex urban assemblages share component/s that each of them claims as exclusive. This situation made necessary practices of co-ordination in which a hierarchy

was established between the competing assemblages, involving important transformations in some of its components.

1. Urban assemblages, power and a

missing bus stop shelter

This paper is about a missing bus stop shelter. This shelter should be located in downtown Santiago, Chile. More precisely, it

should be located on Alameda Bernardo

OHiggins, Santiagos main avenue, a dozen

metres from the corner with MacIver Street.

As a replacement there is a single metallic

bus stop sign that indicates that bus lines

210, 412a and 418 stop there. Also, a

rectangular area closer to the street is

located several centimetres above the sidewalk level and covered by grey and white

striped tiles; yet the rest of the structure

roof, maps, seats, etc.is missing.

While telling the story of why this particular bus stop shelter is missing, the paper

will also tell another story; a story about coordination practices between assemblages

Sebastian Ureta is in the Departamento de Sociologia, Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Chile. Email:

sureta@uahurtado.cl.

0042-0980 Print/1360-063X Online

2013 Urban Studies Journal Limited

DOI: 10.1177/0042098013489747

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

232

SEBASTIAN URETA

enacted by two Chilean public organisations.

The usage of this term is not casual. Deriving

from Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattaris

(1988) concept of agencement, in the past

few years assemblage has gained an important degree of momentum in the social

sciences (Bennett, 2005; De Landa, 2006;

Farias and Bender, 2009; Area, 2011 special

issue 43.2; City, 2011 special section in issues

2 and 34; Marcus and Saka, 2006; Ong and

Collier, 2008). In trying to elucidate the concept, an important starting-point should be

the recognition that

there is no single correct way to deploy the

term, nor does any one theoretical tradition

or style hold an exclusive right to it (Anderson

and McFarlane, 2011, p. 124).

Therefore, instead of a single and consistent

social theory, assemblages should be seen as

part of a more general reconstitution of the

social that seeks to blur divisions of social

material, nearfar and structureagency

(Anderson and McFarlane, 2011, p. 124).

When using the term assemblages, social

scientists are usually referring to multiple

things, from merely a particular research

focus to a completely new ontology of the

social (for a more detailed comparison, see

the table in Brenner et al., 2011, p. 231).

Following the strongest, or ontological,

sense of the term as proposed by Manuel De

Landa (2006) assemblages can be defined as

wholes whose properties emerge from the

interactions between parts (p. 4). Therefore

what defines assemblages as entities is not

their internal wholeness or coherence but,

on the contrary, what De Landa calls their

relations of exteriority (p. 10) or the way

in which the components of assemblages are

not exclusive to them but may be detached

from [them] and plugged into a different

assemblage in which [their] interactions are

different (p. 11); therefore the components

are autonomous; they have agency and

commonly belong to several assemblages at

once. Such exteriority also implies, centrally,

that the properties of the component parts

can never explain the relations which constitute a whole (p. 11). So assemblages are

never fully stable and well-bounded entities;

they do not have an essence, but exist in a

state of continual transformation and emergence. They exist as a process of putting

together, of arranging and organising the

compound of analytical encounters and

relations (Dewsbury, 2011, p. 150). In this

sense, the concept offers the possibility of

grasping how something . heterogeneous

. holds together without actually ceasing

to be heterogeneous (Allen, 2011, p. 154).

Several characteristics derive from this

conceptualisation. First, the notion of

assemblage

emphasises gathering, coherence and dispersion. In particular, this draws attention to the

labour of assembling and re-assembling sociomaterial practices that are diffuse, tangled and

contingent (Anderson and McFarlane, 2011,

p. 124).

Secondly, agency is not located only in key

actors, but largely distributed in several

components of the assemblage whether

human or non-human. Even in the case of

what has been considered the purest locus of

agencyreflective,

intentional

human

consciousnessis from the first moment of

its emergence constituted by the interplay of

human and nonhuman materialities (Bennett,

2005, p. 454).

Thirdly, and because of these multiple agencies, assemblages are always in between what

De Landa (2006, p. 12) calls processes of territorialisation (a relatively defined and stable

identity) and deterritorialisation (a mutable

state, undefined identity). Or, we can say,

they exist but do not exist too much, too

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

CO-ORDINATING ASSEMBLAGES IN SANTIAGO

solidly; existence is a constant accomplishment not a fact and must be constantly reaffirmed. For this reason

an emphasis is placed on fragility and provisionality; the gaps, fissures and fractures that

accompany processes of gathering and dispersing (Anderson and McFarlane, 2011, p. 124).

Finally, this relational ontology implies, on

the opposite side, that the notion of assemblage involves no outside (Farias, 2011, p.

369). An assemblage has no environment; it

is not submerged inside a general framework

such as a structure or ideology. Everything

that matters to the assemblage is related to it

in some way or other; for this reason they

call for a positive description of their

becoming, not external explanations

(Farias, 2011, p. 369).

From this perspective, cities such as

Santiago can be seen as the sum of multiple

assemblages of people, networks, organizations, as well as of a variety of infrastructural components, from buildings and

streets to conduits for matter and energy

flows (De Landa, 2006, p. 4). Such assemblages do not form wholes or totalities, in

which every part is defined by the whole,

but rather emergent events or becomings

(Farias, 2009, p. 15). Therefore, assemblage

urbanism changes the focus of enquiry

from stable structures that relate to each

other in unequal ways to the question of

why and how multiple bits-and-pieces accrete

and align over time to enable particular forms

of urbanism over others in ways that cut

across these domains, and which can be subject to disassembly and reassembly through

unequal relations of power and resource

(McFarlane, 2011a, p. 652).

Such a perspective allows us to move away

from a notion of the city as a whole to a

notion of the city as multiplicity, from the

233

study of the urban environment to the

study of multiple urban assemblages

(Farias, 2011, p. 369).

However, such a conception has also

been criticised, especially in relation to how

assemblage urbanism deals with the issue of

power and inequality in urban dynamics.

Following Sayer (1992), Brenner and

Wachsmuth et al. (2011, 2012) criticise the

assemblage approach for being based on a

naive objectivism or the belief that

the factsin this case, those of interconnection among human and nonhuman actants

speak for themselves rather than requiring

mediation or at least animation through theoretical assumptions and interpretive schemata (Brenner et al., 2011, p. 233).

For this reason, this approach offers no

clear basis on which to understand how,

when and why . some possibilities for

reassemblage are actualised over and against

others that are suppressed or excluded

(Brenner et al., 2011, p. 235).

Answering such criticism, the proponents

of this ontology claim to recognise from the

start that urban assemblages are structured,

hierarchised, and narrativised through profoundly unequal relations of power,

resource, and knowledge (McFarlane,

2011a, p. 655). The very possibility of emergence of a particular assemblage always

takes place in and through an ontology or grammar of power; a cosmos saturated by forces,

defined by trials and tests, by becomings and

encounters, capacities, articulations, enrolments

and alliances (Harrison, 2011, p. 158).

Given that inequality is not explained by the

recourse to structural argumentations, the

focus on urban assemblages is better prepared than traditional political economy of

cities to unveil the actual practices, processes, sociomaterial orderings, reproducing

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

234

SEBASTIAN URETA

asymmetries in the distribution of resources,

of power and of agency capacities, opening

up Blackboxed arrangements (Farias, 2011,

p. 370). Along with this emphasis on opening black boxes, the assemblage approach is

useful for critical analysis on the basis of its

parallel focus on potentiality, or how it

shows

not just the possibilities of assembly, but the

possibilities that remain unfulfilled: potentiality exists as a tension between hope, inspiration and the scope of the possible, and the

sometimes debilitating recognition of that

which has now been attained (McFarlane,

2011b, p. 222).

In this paper, I would like to contribute to

this on-going discussion by exploring in

detail the way in which power emerges in

urban assemblages through the in-depth

study of why there is a missing bus stop

shelter in front of Santiagos Biblioteca

Nacional. In doing this, I will change the

usual analytical focus on the emergence of

assemblages to the controversy arising when

two large and complex urban assemblages

share component/s that each of them claims

as exclusive. Following De Landa (2006

p. 9), we could say that such controversy is

between two contrasting totalisations of

each assemblage in which the component/s

under dispute is/are seen as being constituted by the very relations they have to

other parts in the whole. A part detached

from such a whole ceases to be what it is,

since being this particular part is one of its

constitutive properties. It is in the shifting

management of such controversies

sometimes involving a closure, sometimes

remaining open and unstablethat a key

materialisation of power and inequality on

urban assemblages emerges.

In analysing such an encounter I will

bring into the analysis one particular conceptual device that could be helpful to

enhance the way assemblage theory deals

with the issue of power in urban settings:

co-ordination. As Annemarie Mol (2002,

especially ch. 3) has explored in her study

of the treatment of atherosclerosis in a

Dutch hospital, the recognition that multiplicity is irreducible from ontology does

not mean that anything goes. In order for

entities to hang together across sites, a constant work of co-ordination between their

multiple enactments is required to prevent

distribution from becoming the pluralizing of a disease into separate and unrelated

objects (p. 117). Leaving aside the usual

realist recourse to refer to a preexisting

object, co-ordination becomes the practices through which the various realities of

atherosclerosis are balanced, added up, subtracted. That, in one way or another, they

are fused into a composite whole (p. 70).

As in any other displacement, moving

Mols conception of co-ordination from her

Dutch hospital to my particular case in

Santiago necessarily implies some adaptations. After all, Mols conception refers to

one multiple/single object (atherosclerosis)

being co-ordinated when moving along the

wards of a single hospital. In my case, there

is no one multiple/single object but, at least,

two and their mobilisation involves several

different locations, such as governmental

offices, documents, sidewalks of the city,

pictures, etc. As a result of this situation, coordination practices in the case under study

involve the performance of multiple assemblages of the involved entities in which the

components in dispute are presented as

being divided and/or shared in new ways. A

key point is that such assemblages are always

multiple, usually proposing quite different

arrangements and attributions of the entities

involved. Co-ordination in this case relates

to the different practices and techniques

involved in the stabilisation of one particular

assemblage over the others, a process in

which different tactics of power and

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

CO-ORDINATING ASSEMBLAGES IN SANTIAGO

inequalities are very much present. Such stabilisation, however, is never definitive and

solid. Like any other assemblage, the selected

assemblage is in a process of constant emergence, always open to be transformed, challenged or discarded.

The missing bus stop shelter will be analysed as a humble casualty of the co-ordination practices between two urban assemblages

that emerged during the development of

Transantiago, the new public transport

system of Santiago.1 In the next section, I

describe these two urban assemblages: the

Biblioteca Nacional building and the bus stop

shelters, or Estaciones de Transbordo. Then

the paper will analyse the practices of co-ordination carried out when both assemblages

collided on the corner of Alameda Avenue

and MacIver Street. Finally the paper will

conclude by exploring the utility of the concept of co-ordination to the understanding of

the issue of power in urban assemblages.

2. Two Urban Assemblages of

Santiago

2.1. The Biblioteca Nacional building

According to its official description, the

Biblioteca Nacional of Chile was founded

in 1813, being one of the oldest in Latin

America. During its first century of existence, the library was located in four different buildings in downtown Santiago, being

forced to change locations in order to

house its ever-growing collections. In 1913,

on the occasion of its first centenary, the

construction of a new and definitive building started, located on a block facing

Alameda Bernardo OHiggins, Santiagos

main avenue. The first part of the building

was inaugurated in 1925.

Fifty years later, in December 1976, the

library building was declared a national

monument. Such a declaration had two

235

immediate effects. First, it located the building partially under the control of the Consejo

de Monumentos Nacionales (National

Monuments Council). Established in 1925,

the mission of CMN was to take charge of the

declaration of entities as monuments and,

once declared, to watch for their restoration,

repair, conservation, and signalling (law

17.288) directly or through intermediaries.

What was going to be even more important

for the controversy to be studied here was

Article 11 of this law that established that

any work of conservation, reparation or

restoration [of a national monument] must

be approved in advance by the CMN.

A second consequence of being declared

a national monument, derived from this, is

that the Biblioteca Nacional started to be

enacted in a different way, as can be seen in

the words of Leonardo Duran, an architect

from the CMN

The guidelines of the international agreements regarding restoration, the Athens charter, the Venice charter . several documents

where the general criteria on how to handle

patrimony are given . the international recommendations, say that it is always right

when interposing a newly built object, an

intervention of a new oeuvre over a patrimonial building, that this be the most neutral

expression as possible with regard to texture,

materiality, colour and expression; it must be

neutral and not affect the original building.

Here, Santiago is presented as a city consisting of buildings that are seen as part of

the heritage of the country and must be

protected. The criteria for such a protection

are taken, as affirmed by Duran, from the

charters adopted by the congress of the

International Museums Office in Athens

(1931) and the second International

Congress of Architects and Technicians of

Historical Monuments in Venice (1964).

The second charter, by far the more

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

236

SEBASTIAN URETA

influential, states that the main duty of

conservation organisations is to preserve

monuments in the full richness of their

authenticity. Therefore a monument is

presented as a relatively rigid entity, having

an authentic essence that must be protected.

Given this authentic essence, the daily

usage of the protected building could be

allowed but it must not change the lay-out

or decoration of the building (article 5).

In this same direction, no new construction, demolition or modification which

would alter the relations of mass and

colour must be allowed (article 6). This

protection does not relate to the monument itself but also the sites of monuments must be the object of special care in

order to safeguard their integrity and

ensure that they are cleared and presented

in a seemly manner (article 14). The

words of Duran, then, appear as continuing

this particular version of conservation by

arguing that any kind of intervention in the

building and its environment must be as

neutral as possible, in order to not affect

the original building.

2.2. Estaciones de Transbordo

Estaciones de Transbordo (transfer stations), as the bus stop shelters under study

were technically known, were part of a

public transport policy known as

Transantiago. The starting-point of such

policy was a document entitled Plan de

Transporte Urbano de Santiago or PTUS

published in 2000 (Correa et al., 2000).

The PTUS opening paragraph makes a critical judgement of Santiago by affirming

that

The deterioration of the quality of life in the

city of Santiago, caused by a rise in vehicular

congestion and environmental pollution,

along with the low levels of service offered by

public transport, is a cause of concern for the

government and all its inhabitants (Correa

et al., 2000, p. 1).

There was a clear connection between the

poor state of the public transport system

and a city where the quality of life had

deteriorated. Together with an ageing bus

fleet, such poor shape was evident in the

existent transport infrastructure, described

by the PTUS as highly deficient, especially

as the routes move away from the centre of

the city, becoming almost inexistent on the

periphery (p. 31). Along with the lack of

some very basic items of the public transport infrastructure in several areas of the

city (especially in low-income boroughs),

the rest of the system was characterised by

the high heterogeneity of the available

infrastructure.

As the main catalyst of a change in this

situation, the PTUS proposed a series of radical transformations in the way the public

transport system of the city had been organised previously. From one day to the next,

almost every single aspect of the public

transport system of the city was going to

change: buses, routes, payment system,

actors involved, information system, etc.

(for a detailed description, see Munoz and

Gschwender, 2008). The final aim of these

transformations was not only to improve the

public transport system, but to transform

the city as a whole. Here, Santiago was portrayed as a city that did not have the kind of

modern public transport system and infrastructure it deserved, especially in the context of the development of the country in the

past 15 years, and the plan was seen as a key

contribution to its transformation into a

world-class city (Maillet, 2008). Therefore,

the PTUS, like most policy proposals, was

centrally about what McFarlane calls potentiality or

the relation between the actual and the virtual

citybetween what ostensibly is and what

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

CO-ORDINATING ASSEMBLAGES IN SANTIAGO

might be or could have beenand thereby

speaks both to the urban imagination, the

sense of possibility that the city can generate

(McFarlane, 2011a, p. 654).

It was, in all, an argument about the future,

about what could be.

In order to implement the measures proposed by the PTUS, at the time renamed

Transantiago, in 2002 the government created the Coordinacion de Transantiago (or

CdT) housing it at the Ministry of Public

Works, Transport and Telecommunications.

From the start, one of the main constraints of

the CdTs work was the limited public funding available to implement Transantiago, a

situation that directly affected the ambitious

infrastructural scheme proposed by the

PTUS. As a result, most of the devices that

involved a high level of investment were

rescheduled to be built over a longer period

of time than originally planned or reduced in

scale to fit into the available budget. In practice, by late 2006 when the plan was originally

scheduled to start2 the only piece of built

infrastructure that was certainly going to be

available would be transfer stations.

These stations, formed by a variable

number of single bus stop shelters connected

by ramps and alleys, occupied a central role

in the new network organisation proposed

by Transantiago. In the existing public

transport system, most bus routes crossed

the city from one end to the other, making

the need for users to transfer between different bus routes and/or to the underground

network quite low. For this reason, bus stops

were quite modest and almost invisible pieces

of urban infrastructure. This was related not

only to their poor shape and heterogeneity,

but also to the extended practice among passengers of accessing and leaving buses wherever they wanted along the route, only subject

to the goodwill of drivers in stopping the bus

(something that they usually did, because

their income was directly related to the

237

number of tickets sold). In these circumstances bus stops were merely one point more

among many others where the bus could stop

and not necessarily be the most used.

Yet in Transantiago, this arrangement

was going to change radically. Not only

could users combine different bus and

underground lines paying a single fare but

also, and more centrally, the reconfiguration of the bus network into a feeder-trunk

scheme made such combinations compulsory in order to reach most destinations. So,

transfer stations were not only bus stops,

but places where most of these compulsory,

and relatively new, connections between

different bus lines and/or the underground

network would take place. For this reason,

the CdT was looking for a piece of architecture with high visibility, which could, without the necessary intervention of other

agents, attract users and guide them in the

right direction.

The relevance of visibility was clear in the

call for tenders for the design of transfer stations published in September 2003. Besides

their functionality, the call stated that the

designs must transcend being only a transport infrastructure solution. They must

become an architectural and urban asset

(MOPTT, 2003, p. 25). In order to become

such an asset the design must not only show

a clear and precise architectural concept (p.

25) but also be an expression of permanency and modernity, using design as an element of high technology, showing the public

character of the station and becoming a

functional element of the transport infrastructure (p. 25). Thus, beyond their daily

visibility for users, and in the absence of

other major infrastructural devices, they

were going to become the most visible materialisation of the new urban assemblage proposed by Transantiago, a mixture of the

permanency and modernity that supposedly characterises transport infrastructure

in world-class cities.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

238

SEBASTIAN URETA

Such an emphasis was acknowledged by the

actors hired to design the transfer stations in

late 2003. After one year of work, they delivered a design in which, in accordance with the

presentation accompanying the plans

[Transfer stations have] an identity that sets

them apart from the rest of the urban furniture

and the rough municipal bus stops . the presence of the bus stops from TRANSANTIAGO

throughout the city will be clearly identifiable,

without being repetitive, being a contemporary

design in tune with the vanguard of the new

project which is the public transport system of

our city (archives of the CMN).

As the quote describes, transfer stations were

designed to be different, to stand out from

the rest of the urban infrastructure of the

city in order both to attract daily users and

to embody the discourse about modernity

and world-class status included in the PTUS.

However, and in contrast with the Biblioteca

Nacional building, such a visibility did not

look to preserve a version of the past, but to

materialise a future urbanity promised by

Transantiago.

Such a situation required a work of coordination between both organisations.3 Its

starting-point was a meeting in March 2004

at the CMN offices where actors from CdT

provided antecedents about Transantiago

and the transfer stations that they were planning to build. After studying this information, in June of that year the CMN sent a

letter back demanding, among other issues,

detailed plans of any transfer stations located

near monuments.

Along with sending the plans in

November 2004, the CdT sent a lengthy

letter providing the arguments behind the

particular designs of transfer stations. It concluded with the following two paragraphs

3. Co-ordinating Assemblages

The presence of the Transfer Stations of

Transantiago throughout the city will generate a new image. On the one hand it will

include a contemporary design that will be

in line with the vanguard of this new project,

the public transport of our city, it will present itself as a new urban referent at every

point and it will be perceived as a total intervention of the city and, on the other hand, it

is designed so that the pedestrian who in a

quotidian way makes transfers identifies with

his/her bus stops, because its different and

in some sense unique.

After the designs were accepted internally by

the CdT, the construction of the transfer stations started in several locations throughout

the city. Most of them were built without

any more hassle than that expected when

dealing with the obduracy (Hommels, 2005)

of the existing urban infrastructure. Some of

them, however, encountered a different kind

of obduracy, much harder to deal with. This

was the obduracy of national monuments

protected from any transformation in their

authentic disposition by the CMN. As a

consequence any transfer station located in

the vicinity of a monument would have to

be approved by them before being built.

Finally, it is relevant to point out that in the

diversity of contexts in which the Transfer

Stations [are located] and especially . in

front of Historical or Public Monuments, it

is sought to fully respect our patrimony,

adapting to the existent context with the

highest possible discretion, defining the type

of roof very cautiously. But it is of the interest of the project within its global context,

to maintain the spirit that every user can

feel identified by his/her bus stop, by his/her

Transfer Station, and, for this, it is relevant

to be able to differentiate in this case the

bus stops with the moderation that is

required by our Cultural Patrimony

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

CO-ORDINATING ASSEMBLAGES IN SANTIAGO

(archives of the CMN; italics and bold in the

original).

In this extract we again can see the performance of a version of the transfer stations

as highly visible entities, an element of

contemporary design that materialises

and unifies the modernity promised by

Transantiago, besides its functional use as a

guide to passengers. The use of italics and

bold characters in the last lines of the paragraph show the importance that the CdT

gave to this particular version of the assemblage. Even in a context where national

monuments are located, the transfer stations should remain relatively immutable.

They should always keep a certain degree of

visibility to stand out in each one of their

concrete urban locations.

After checking the provided plans, the

actors at the CMN asked for several stations

to be relocated, something that the CdT

accepted and most of the controversial

issues were settled relatively quickly. There

was only one exception: shelter 7 from Santa

Luca transfer station that, in accordance

with the plans, had to be built in the middle

of the block occupied by the Biblioteca

Nacional.

At the beginning of 2005, the CMN sent

a letter to the CdT asking for the removal

of this particular shelter in order to avoid

an obstacle in viewing the patrimonial

building. Here we see a performance of

Biblioteca Nacional as an assemblage that

has to be protected. However, this protection did not refer to the material structure

of the building, but to its view. This is a

much more ambiguous claim. Strictly

speaking, law 17.288 talks about the CMN

having regulatory attributions regarding

the conservation, reparation or restoration of monuments, not about their view.

From the words of Duran, quoted earlier,

we can conclude that view was certainly

included by the members of the CMN in

239

the conservation attributes. Yet this did

not solve the problem; it does not clarify

what the view of the Biblioteca Nacional

exactly is and/or how it might be affected

by building transfer station 7 in its surroundings. Given the lack of any previously

set standards, the characteristics of this

view and how both buildings were going to

relate to it needed to be determined in the

process of argumentation itself.

Visibility, as any other component of an

assemblage, is always relational. It does not

belong to the object but is a relation between

itself and other entities in its vicinity.

Especially in a cityscape populated by multiple objects, to increase the visibility of one

(or to add a new visible one) normally

speaking means to decrease the visibility of

other/s. This is fine when the visibility of

such objects is not considered relevant, but

it becomes an issue when it is protected as

in the case of Biblioteca Nacional, or forms

a central component of its design and

attached function as happened with the

transfer station. In this case, we can see how

the territorialisation of an assemblage,

understood as the processes that define or

sharpen the spatial boundaries of actual territories (De Landa, 2006, p. 13), is directly

related to a certain deterritorialisation of

other/s. The territorialisation of the transfer

station as a highly visible entity in this particular location implied, from the point of

view of the CMN, the deterritorialisation of

the Biblioteca Nacional building as a monument with certain heritage views that must

be protected.

In their reply to this letter, in July, the

CdT argued that it was impossible to move

the shelter from this block given that it will

imply to significantly increase the distances

that the public transport user has to walk,

because there is no other position close by to

locate the bus stop. So, instead of agreeing

to deal with the issue in terms of a monument whose view has to be protected, they

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

240

SEBASTIAN URETA

maintained an assemblage in which the bus

stop in this location represented not only a

highly visible entity, but mainly a materialisation of the users right to accessible public

transport.

This move was acknowledged by the

CMN who, in a letter sent in August, argued

that this particular bus stop must be moved

for three reasons

I. The use of the sidewalk in front of the

main access to the Biblioteca Nacional

has currently collapsed, given its narrowness and the great influx of people.

II. For this reason to locate a transfer station precisely in this place will end up

causing a disorder in the flow and circulation of pedestrians, altering the space

of the sidewalk, the anteroom or atrium

of such a noble building.

III. To avoid that the view of the historical

monument be blocked (archives of the

CMN).

In this extract, the CMN brought new elements into the Biblioteca Nacionals assemblage. While in point III we can again see it as

a site of a heritage building whose view needs

to be protected, the other two points are much

more connected with the argument proposed

by the CdT. Instead of bringing entities to

argue about the validity of a view in itself as a

reason to move the bus stop, they portrayed

the area surrounding the building as also containing an important number of pedestrians

who were going to have problems in their

mobility due to the presence of the bus stop.

This strategy proved to be the wrong one

for the purposes of the CMN. It is in a city of

moving people where CdT moved more at

ease, having several kinds of technical device

from transport planning to bring in support

of their position. This was clear in the letter

in answer to the request of the CMN sent in

October. Using several different quantifications they argued that the flow of people in

front of the Biblioteca Nacional would not

be affected at all by locating the shelter in the

block and, besides, that it was impossible to

move it anywhere else. In order to mitigate

such a situation they offered to enlarge the

sidewalk by 1.5 metres.

Regarding the performance of the library

as an heritage building whose view should

be protected, their strategy was to minimise

the visual impact of the shelter. First, they

offered to divide bus stop 7 into two smaller

sub-shelters named 7a and 7b and move

them to the two extremes of the block in

order not to obstruct the central body of

the building. Secondly, they included an

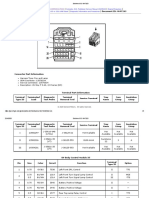

image in order to visualise the impact of the

shelter on the view of the library, as shown

in Figure 1.

This was not merely illustrative. As a long

line of studies of scientific and technical

practices have shown, visualisations have a

certain agency of their own. First of all, they

are irreplaceable as documents which enable

objects of study to be initially perceived and

analyzed (Lynch, 1985, p. 37). However, this

is not their only attribute. Scientific and/or

technical visualisations are also endowed with

what Soderstrom (1996) calls external efficacy

or the persuasive power of representations

(p. 62). Given the complex technical processes

needed to produce them, these visualisations

are usually seen as more valid than other

forms of representation, especially by actors

outside the particular expertise that produced

them. For both reasons contemporary urban

planning has become highly dependent on

such devices to the degree that very few working practices are done without the active

presence of different kinds of visualisations, from plans to models (for a detailed

exploration of this issue, see Duhr, 2007).

Especially in controversial issues, visualisations are quite helpful because they render

what are highly positioned notions of space

. as universally applicable and desirable

(Lepawsky, 2005, p. 707).4

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

CO-ORDINATING ASSEMBLAGES IN SANTIAGO

241

Figure 1. The CdTs visualisation of the proposed bus shelters, 7a and 7b, in front of the

Biblioteca Nacional.

Source: CMN Archives.

In this sense, Figure 1 can be seen as

offering a particular kind of visual assemblage of the space surrounding Biblioteca

Nacional. A first thing to note is the character of this visualisation. Instead of presenting a proper plan or model, they choose to

use as the basis for the visualisation an

actual photograph of the building taken

from the other side of Alameda, superimposing over it a computational representation of the proposed shelters 7a and 7b. By

doing this, they create a hybrid in which

both the existing building and the future

infrastructure co-exist, endowing a higher

degree of plausibility to their proposal. In

parallel, the inclusion of several other entities in the picture looked to weaken the

position of the CMN. Future shelters 7a

and 7b, especially the one on the right, are

also represented as partially hidden behind

several objects that currently block the view

of the Biblioteca Nacional, such as passing

cars and buses and trees growing on the

divide in the middle of the avenue. At the

top right-hand side of the library we can see

two new buildings and a piece of infrastructure also interfering with the view. In all,

the image represents the staging of a scenography in which attention is focused on one

set of dramatized inscriptions (Latour,

1990), in particular the happy co-existence

of the Biblioteca Nacional and the shelters,

especially given that the existing purity of

the view of the Biblioteca Nacional was

quite questionable.

However, this picture was the closest that

shelter 7 ever came to existing. As Latour

(1990) has stated, visualisations do not work

on their own. To be really effective, they

need to mobilise along with them several

other entities that contribute to re-enact

their facts in new locations. In this case, the

image in Figure 1 was presented only with

the arguments that the CdT has been stating

(and the CMN rejecting) all along. In the

end, the visualisation failed to convince the

CMN and in November 2005 they sent a

letter making the same argument as the one

in August, but using stronger terms and concluding that the bus stops must be moved

definitely.

The authoritative tone of this letter was

based on their inclusion in the controversy

of a metrology in which the positions of

both organisations could be finally balanced:

legal bodies. By doing this, they not only

established a common ground for discussion

but also, and centrally, a hierarchy. Such

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

242

SEBASTIAN URETA

hierarchy was based on the different weight

of the legal bodies behind each organisation.

While the CdT was supported by a quite diffuse presidential decree of 2002, that did not

even detail its legal attributions, law 17.288

supported the CMN in full. Even more, in its

eighth article, this law establishes that civilian, military and police authorities will have

the obligation to co-operate with the fulfillment of the functions and resolutions that

the council adopts in relation with the conservation, care and vigilance of National

Monuments. So, in any controversy involving the conservation of a national monument, even in the case of its ambiguous view,

the CMN was always going to have the last

word.

Notwithstanding, the position of the CdT

was not completely lost, as can be seen in the

following extract from their final letter on

this subject sent to the CMN in June 2006.

The National Monuments Council had asked

to move the bus stop to the next block from

MacIver Street, thinking of the important

influx of people on such a block and, the disruption that this was going to cause to the

entrance of such a building and the visual

blocking of a historical monument. . From

the above mentioned point, it can be concluded

that the central worry [of the CMN] is the

important influx of people that the sidewalk of

the Biblioteca Nacional is going to experience,

that sadly is going to exist with independence

of the bus stops being installed. Nevertheless, it

is possible to avoid the visual obstruction by

eliminating the bus stop shelter and only contemplating the construction of platforms and

the respective [bus stop] signals. (archives of

the CMN, underlined in the original)

Bringing the position of the CMN again

into the performance of the library as surrounded by flows of moving people (the

central worry [of the CMN] is the important influx of people .), they were able to

use their greater fluency in transport issues

to maintain the location of the bus stops,

concluding (possibly not without irony)

that such influx was sadly . going to exist,

with independence of the bus stops being

installed [there].

However, in locating the transfer stations

there, they could not ignore the performance of the Biblioteca Nacional as having

a view that must be protected by the CMN

and including law 17.288. In this respect,

the CdT ended up proposing the removal

of only the platform, but not the rest of the

structure of the transfer station in this particular location. In order to illustrate their

proposal, they added a new visualisation,

shown in Figure 2. Here we have a different

composition of the view of the Biblioteca

Nacional from that shown in Figure 1. This

time, the picture on which the visualisation

is based was taken standing on the divide in

the middle of Alameda Avenue, 50 metres

or so down the street. It was also taken at a

moment with less trafficthere is only one

small truck coming down the street. The

shelter from transfer station 7 is also missing and the only remnant of Transantiagos

proposed infrastructure is the pale red line

marking the area where the sidewalk would

be extended. As a consequence, the view of

the building appears to be much clearer,

with only a few palm trees and passing

pedestrians blocking it.

By doing this, and contrary to the CDTs

earlier claims about the immutability of its

design, transfer stations proved to be a quite

fluid entity (de Laet and Mol, 2000), being

able to adapt, to be transformed in order to

create a new assemblage including both the

transfer stations and the Biblioteca

Nacional. However, such fluidity was not

without costs. In order to form this new

assemblage, the station had to dispense with

most of its structure above ground level. By

doing this, it was able to keep being the

point at which pedestrians would turn into

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

CO-ORDINATING ASSEMBLAGES IN SANTIAGO

243

Figure 2. The CdTs visualisation of the Biblioteca Nacional without the shelters.

Source: CMN Archives.

public transport users, but sacrificing its

related embodiment of the modern city

promised by Transantiago. Or, in other

words, Transantiagos modernity was deterritorialised in order for the library to maintain its territorialisation as a heritage

building whose view is protected. Therefore,

in this particular context, the view could

not be sharedas an element in common

between the Biblioteca Nacional and the

shelter of the transfer stationbut the totalising claim over it of the former prevailed.

Conclusions

When Transantiago started its operation in

February 2007, most of the 35 original

transfer stations were already built. Beyond

a few pieces in the media with architects criticising their shape in aesthetic terms, they

attracted very little public attention. Also,

they were effective in becoming highly visible

pieces of urban infrastructure, contributing

to the disappearance of the former practice

of drivers letting passengers on and off the

bus anywhere they wanted. Taking into consideration that almost no other aspect of the

plan seemed to be functioning as expected,

transforming Transantiago into one of the

biggest controversies in the country since the

return of democracy in 1990 (Munoz and

Gschwender, 2008), transfer stations could

be seen as one of the very few uncontroversial entities of the early implementation.

This success, however, was not complete.

Shelter 7 of Santa Lucia station proved to be

too visible, too remarkable, in a space where

visibility was already monopolised by

another entity. Under these conditions, the

path taken was to transform the station into

a fluid object, removing the shelter and

most of its elements above ground level, and

hence its visibility, thus allowing the coexistence of both entities in the same block.

At first, we can say that the CMN finally

won over the CdT, with the Biblioteca

Nacional remaining immutable/total while

the transfer station was forced to become

fluid. Yet this is only part of the story. As

explored by the practitioners of actor

network theory, the fluid character of entities, their capacity to change continually,

might also be an advantage. As affirmed by

de Laet and Mol

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

244

SEBASTIAN URETA

in travelling to unpredictable places, an

object that isnt too rigorously bounded, that

doesnt impose itself but tries to serve, that is

adaptable, flexible and responsivein short,

a fluid objectmay well prove to be stronger

than one which is firm (de Laet and Mol,

2000, p. 226).

Therefore, if we take contemporary cities as

constituted by shifting geographies, by

ever-evolving assemblages that relate to

each other in multiple ways, the immutability/totality of a building like the Biblioteca

Nacional does not constitute an asset; on

the contrary it is likely to lead to rupture,

difference, and distance (Law and Mol,

2001, p. 614). This is exactly what happened here, when the versions about the

city of the past and the one of the future

could not be put together into an assemblage that included both, ending up sacrificing one of them.

Along with exploring this particular case,

the analysis made in this paper looked to

contribute to the development of assemblage urbanism in several ways. First of all is

the issue of methods. Moving away from

grand analyses or urban trends, a focus on

urban assemblages leads us to investigate

previously neglected dimensions of capitalist urbanization (Brenner et al., 2011,

p. 231). Given its emphasis on the dynamic

and ever-shifting emergence of urban entities, assemblage urbanism tends to favour

the study of the very concrete practices

through which the urban is continually produced, no matter how small or context-specific. In particular, this article dealt with the

practices of co-ordination between two

organisations enacting contrasting assemblages of a very particular urban location. In

doing this, it focused on following the territorialisations/deterritorialisations occurring in the process, or the ways in which

each utterance made by the involved actors

implied the territorialisation of certain

assemblages and the deterritorialisation of

others. The documents and visualisations

produced by the actors involved in the controversy were studied as complex spatial

narratives on their own, ordering a variable

number of entities in the shape of a particular territory that included and excluded

certain assemblages. Such a focus reorientates the research not only as the analysis of

existing urban entities, but also as the study

of the multiple practices through which

urbanism is achieved as a play of the actual

and the possible (McFarlane, 2011a,

p. 652).

In the second place, the paper hoped to

contribute to current debates about the

(supposed) problems of assemblage urbanism in dealing with issues of power and

inequality. When we move from just

describing the performance of single assemblages to the co-ordination practices

between two (or more) of them sharing elements over which they claim exclusivity,

power and inequality appear in all their

force. Through the ensuing co-ordination

practices, the competing assemblages

become entangled in multiple hierarchical

relations. Such hierarchies are given by

their different position in metrologies

introduced as a way to balance their relative

weights, as seen here in the case of legal

bodies. It is exactly in these multiple hierarchies that a great deal of power in assemblages resides,5 enhancing or restricting,

even forbidding, the capacity of assemblages to territorialise in different times

and/or spaces, to re-enact in some ways

and not others. This kind of power itself is

always relational, it exists not as something

intrinsic to urban entities but always as an

exteriority of relations, using de Landas

term, or as the sum of unequal relationships in which a certain urban assemblage

becomes entangled.

Finally, the paper has hoped to contribute to the development of a more fluid

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

CO-ORDINATING ASSEMBLAGES IN SANTIAGO

understanding of urban spaces. As the case

under study showed, urban assemblages are

always emerging, continually entangled in

relations of territorialisation/deterritorialisation. Even hierarchies themselves change

continually, readapting to the emergence of

new metrologies and the multiple assemblages whose relations they regulate. So

does power. Then the space constituted by

such assemblages, their power and hierarchies, should be seen as ever-shifting, even

if its pace is so slow that it appears as completely static. Even monuments such as the

Biblioteca Nacional, the epitome of urban

stability, are continually changing as they

come to be related to new entities and react

to them, even such humble ones as a single

bus stop shelter. Then assemblage urbanism

invite us to see spaces not as composed of

stable and well-bounded objects which

naturally embody power, but as fluid

entanglements of entities whose power is a

temporary achievement that must be continually reasserted through complex co-ordination practices.

Funding

In writing this article, The author acknowledges

funding from CONICYT and Marie Curie

International Incoming Fellowships (grant

numbers 11060348 and PIIF-GA-2009-235895

respectively).

Notes

1. This description is based on the material collected by the author while doing fieldwork in

Santiago between 2007 and 2009. Fieldwork

consisted mainly of (1) in-depth interviews

with actors involved in the design of

Transantiago and daily users of the system,

(2) gathering of several materials in the form

of research reports, papers, presentations,

etc. and (3) participant observation of practices of daily usage of the system. All the

names of the actors involved have been

changed in order to protect their anonymity.

245

2. After two delays, Transantiago finally started

on February 2007.

3. At no point had such co-ordination processes included any other public/private

organisation or transcended to the media or

the wider public, not even after Transantiago

started. For this reason the analysis will only

consider the CdT and the CMN.

4. Urban planning in Chile has not been indifferent to this trend. Since the late 1960s,

especially connected with the development

of the first university departments of planning and transport engineering, sophisticated

visualisation devices have been at the very

centre of urban planning in the country

(Gross, 1991). This trend was strengthened

after the return of democracy in 1990, when

a substantive group of academic actors came

to occupy key positions in the government

(Silva, 2008, ch. 6), bringing with them different kinds of up-to-date visualisation

devices that were actively used to demarcate

their area of expertise from other political

actors (for an example in the public transport area, see SECTRA, 2000).

5. However, not all of it. Power could also be

of other kinds, such as the power to completely exclude competing entities from any

comparison (as happens during dictatorial

regimes), denying even the possibility of

being balanced into a common metrology.

References

Allen, J. (2011) Powerful assemblages?, Area,

43(2), pp. 154157.

Anderson, B. and McFarlane, C. (2011) Assemblage and geography, Area, 43(2), pp.

124127.

Bennett, J. (2005) The agency of assemblages and

the North American blackout, Public Culture,

17(3), pp. 445466.

Brenner, N., Madden, D. and Wachsmuth, D.

(2011) Assemblage urbanism and the challenges of critical urban theory, City, 15(2),

pp. 225240.

Correa, G., Abedrapo, E., Gonzalez, S. and

Sols, S. (2000) Plan de transporte urbano de

Santiago 20002010. Ministerio de Obras

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

246

SEBASTIAN URETA

Publicas, Transporte y Telecomunicaciones,

Santiago.

De Landa, M. (2006) A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity.

London: Continuum.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1988) A Thousand

Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

London: The Athlone Press.

Dewsbury, J.-D. (2011) The DeleuzeGuattarian

assemblage: plastic habits, Area, 43(2), pp.

148153.

Duhr, S. (2007) The Visual Language of Spatial

Planning: Exploring Cartographic Representations for Spatial Planning. London: Routledge.

Farias, I. (2009) Introduction: decentring the

object of urban studies, in: I. Faras and T.

Bender (Eds) Urban Assemblages: How Actor

Network Theory Changes Urban Studies, pp.

124. London: Routledge.

Farias, I. (2011) The politics of urban assemblages, City, 15(3/4), pp. 365374.

Farias, I. and Bender, T. (Eds) (2009) Urban

Assemblages: How ActorNetwork Theory

Changes Urban Studies. London: Routledge.

Gross, P. (1991) Santiago de Chile (19251990):

Planificacion Urbana y Modelos Politicos,

EURE, 17(52/53), pp. 2752.

Harrison, P. (2011) Fletum: a prayer for X, Area,

43(2), pp. 158161.

Hommels, A. (2005) Unbuilding Cities: Obduracy

in Urban Sociotechnical Change. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Laet, M. de and Mol, A. (2000) The Zimbabwe

bush pump: mechanics of a fluid technology,

Social Studies of Science, 30(2), pp. 225263.

Latour, B. (1990) Drawing things together, in: M.

Lynch and S. Woolgar (Eds) Representation in

Scientific Practice, pp. 1860. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press.

Law, J. and Mol, A. (2001) Situating technoscience: an inquiry into spatialities, Environment and Planning D, 19, pp. 609621.

Lepawsky, J. (2005) Stories of space and subjectivity in planning the Multimedia Super Corridor, Geoforum, 36(6), pp. 705719.

Lynch, M. (1985) Discipline and the material form

of images: an analysis of scientific visibility,

Social Studies of Science, 15(1), pp. 3766.

Maillet, A. (2008) La gestacion del Transantiago

en el discurso publico: hacia un analisis de

polticas publicas desde la perspectiva cognitivista, in: M. de Cea, P. Diaz and G. Kerneur

(Eds) Chile de pas modelado a pas modelo:

Una mirada sobre la poltica, lo social y la economa. Santiago: LOM.

Marcus, G. and Saka, E. (2006) Assemblage,

Theory, Culture & Society, 23(2/3), pp.

101106.

McFarlane, C. (2011a) The city as assemblage:

dwelling and urban space, Environment and

Planning D, 29(4), pp. 649671.

McFarlane, C. (2011b) Assemblage and critical

urbanism, City, 15(2), pp. 204224.

Mol, A. (2002) The Body Multiple: Ontology in

Medical Practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

MOPTT (Ministerio de Obras Publicas Transportes y Telecomunicaciones) (2003) Bases

de Consultora: Diseno de Estaciones de Transbordo para Transantiago. Coordinacion General de Concesiones, MOPTT, Santiago.

Munoz, J. C. and Gschwender, A. (2008) Transantiago: a tale of two cities, Research in Transportation Economics, 22, pp. 4553.

Ong, A. and Collier, S. J. (Eds) (2008) Global

Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics

as Anthropological Problems. Malden, MA:

John Wiley & Sons.

Sayer, A. (1992) Method in Social Science: A Realist Approach. London: Routledge.

SECTRA (Secretara de Planificacion de Transporte) (2000) Resumen Ejecutivo del Plan de

Transporte Urbano de Santiago, 20002006.

Subsecretaria Interministerial de Transportes,

Gobierno de Chile, Santiago.

Silva, P. (2008) In the Name of Reason, Technocrats and Politics in Chile. University Park, PE:

The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Soderstrom, O. (1996) Paper cities: visual thinking in urban planning, Cultural Geographies,

3(3), pp. 249281.

Wachsmuth, D., Madden, D. and Brenner, N.

(2011) Between abstraction and complexity:

meta-theoretical observations on the assemblage debate, City, 15(6), pp. 740750.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD ALBERTO HURTADO on December 24, 2013

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Parts Manual NDR 030 AE, NR 035 AE, NR 040 AE, NR 045 AE (C815) NS 040 AF, NS 050 AF (C816)Документ232 страницыParts Manual NDR 030 AE, NR 035 AE, NR 040 AE, NR 045 AE (C815) NS 040 AF, NS 050 AF (C816)Erisson100% (5)

- Thrift (2008) Where Is The Subject?Документ8 страницThrift (2008) Where Is The Subject?Nico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- MRO Report-FINAlДокумент60 страницMRO Report-FINAlKeval8 VedОценок пока нет

- Natural Gas VehiclesEIAДокумент84 страницыNatural Gas VehiclesEIAEduardo EnaОценок пока нет

- 2015 - Epistemic Dissonance. ReconfiguriДокумент21 страница2015 - Epistemic Dissonance. ReconfiguriNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- VHF FM8500 Operator's Manual K2 9-12-05 PDFДокумент99 страницVHF FM8500 Operator's Manual K2 9-12-05 PDFsrinu1984100% (1)

- Itinerary of Travel: Republic of The Philippines Ramon Magsaysay Technological University Iba, ZambalesДокумент11 страницItinerary of Travel: Republic of The Philippines Ramon Magsaysay Technological University Iba, ZambalesIndustrial TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Ontology and Indigeneity On The Politica PDFДокумент11 страницOntology and Indigeneity On The Politica PDFNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- CONVEYORДокумент5 страницCONVEYORAditi Bazaj100% (1)

- The Gift of A Vocation: Learning, Writing, and Teaching SociologyДокумент11 страницThe Gift of A Vocation: Learning, Writing, and Teaching SociologyNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Social MethodsДокумент18 страницSocial MethodsNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Isolation in Globalizing Academic FieldsДокумент57 страницIsolation in Globalizing Academic FieldsNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Webb 2012Документ22 страницыWebb 2012Nico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Career Coupling Career Making in The Elite World of Musicians and ScientistsДокумент21 страницаCareer Coupling Career Making in The Elite World of Musicians and ScientistsNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Herzog 1983 Cereer Patterns of Scientists in Peripheral CommunitiesДокумент9 страницHerzog 1983 Cereer Patterns of Scientists in Peripheral CommunitiesNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Tommaso Venturini, Pablo Jensen and Bruno Latour (2015) Fill in The Gap. A New Alliance For Social and Natural SciencesДокумент4 страницыTommaso Venturini, Pablo Jensen and Bruno Latour (2015) Fill in The Gap. A New Alliance For Social and Natural SciencesNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Baselining Pollution: Producing Natural Soil' For An Environmental Risk Assessment Exercise in ChileДокумент15 страницBaselining Pollution: Producing Natural Soil' For An Environmental Risk Assessment Exercise in ChileNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- CienfuesgosДокумент8 страницCienfuesgosNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Building A Park Immunising Life EnvironmДокумент9 страницBuilding A Park Immunising Life EnvironmNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- The Pleasures, Pain and Promise of Sociological Work Outside The Academy The Sociological ImaginationДокумент11 страницThe Pleasures, Pain and Promise of Sociological Work Outside The Academy The Sociological ImaginationNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Authorship Practices and Institutional C PDFДокумент27 страницAuthorship Practices and Institutional C PDFNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Dianne Hagaman - Articles - About PhotographyДокумент21 страницаDianne Hagaman - Articles - About PhotographyNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Application For The Issue of Additional TRFsДокумент1 страницаApplication For The Issue of Additional TRFsNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Warde 2014 Food Studies and The Integration of Multiple MethodsДокумент22 страницыWarde 2014 Food Studies and The Integration of Multiple MethodsNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- CHEN 2011 Studying Harm Reduction PolicyДокумент7 страницCHEN 2011 Studying Harm Reduction PolicyNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- r106 Chernilo HabermasДокумент29 страницr106 Chernilo HabermasNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- GOMART 2002 METHADONE - Six Effects in Search of A SubstanceДокумент44 страницыGOMART 2002 METHADONE - Six Effects in Search of A SubstanceNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Law 1986 Methods of Long Distance ControlДокумент31 страницаLaw 1986 Methods of Long Distance ControlNico SanhuezaОценок пока нет

- Ce313 Highway and Railroad Engineering Assignment 4Документ8 страницCe313 Highway and Railroad Engineering Assignment 4ST. JOSEPH PARISH CHURCHОценок пока нет

- Aaj 130 Mar 1960Документ47 страницAaj 130 Mar 1960Alain PiquetОценок пока нет

- Agreement Between Uber and GMR Green EnergyДокумент8 страницAgreement Between Uber and GMR Green EnergyraiutkarshОценок пока нет

- Surface Drain Channels: Jeevan Bhar Ka Saath..Документ2 страницыSurface Drain Channels: Jeevan Bhar Ka Saath..arjun 11Оценок пока нет

- Design Report Eco Kart Team Exergy.Документ19 страницDesign Report Eco Kart Team Exergy.Upender Rawat50% (2)

- Design of A Pedestrian-Steel Bridge Crossing Auchi-Benin ExpresswayДокумент9 страницDesign of A Pedestrian-Steel Bridge Crossing Auchi-Benin ExpresswaySabin MaharjanОценок пока нет

- Abstract Problem Statement Objectives Specific ObjДокумент37 страницAbstract Problem Statement Objectives Specific ObjYohans EjiguОценок пока нет

- Tax 2017 Bar Q&aДокумент12 страницTax 2017 Bar Q&aRODNA JEMA GREMILLE RE ALENTONОценок пока нет

- BL Master: Coffe World CorporationДокумент4 страницыBL Master: Coffe World Corporationwendy ramonОценок пока нет

- Econ - Article1Документ3 страницыEcon - Article1Nicah AcojonОценок пока нет

- DHL Mainline AwbДокумент5 страницDHL Mainline AwbVictor Lo Dastek UnichipОценок пока нет

- Vijay HiranandaniДокумент25 страницVijay HiranandaniNanda Win LwinОценок пока нет

- Medical Application of BLDCДокумент5 страницMedical Application of BLDCAbd Al HAmidОценок пока нет

- Territorial Waters or A Territorial SeaДокумент14 страницTerritorial Waters or A Territorial SeaAditya VermaОценок пока нет

- CD150MДокумент2 страницыCD150MVentasVarias AntofaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 6 Hydraulics and PneumaticsДокумент29 страницChapter 6 Hydraulics and Pneumaticsadaptive4u4527Оценок пока нет

- Paulding County Progress November 12, 2014Документ24 страницыPaulding County Progress November 12, 2014PauldingProgressОценок пока нет

- XXXДокумент5 страницXXXDương Thanh GiangОценок пока нет

- Han MaekДокумент50 страницHan MaekAnonymous B1AOOsmRMiОценок пока нет

- NFSW Car Rankings and LeaderboardsДокумент5 страницNFSW Car Rankings and LeaderboardsDragoș L. I. TeodorescuОценок пока нет

- Body Control Module X5Документ3 страницыBody Control Module X5Men PanhaОценок пока нет

- Act 1 1 1historycivilengineeringarchitecureДокумент3 страницыAct 1 1 1historycivilengineeringarchitecureapi-247437088Оценок пока нет

- SEN301previousexamquestions PDFДокумент22 страницыSEN301previousexamquestions PDFM MohanОценок пока нет

- Crash Test Results 2005Документ17 страницCrash Test Results 2005api-3850559100% (2)