Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Judge Order - DeSisto Case

Загружено:

Dave Biscobing0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

5K просмотров13 страницA superior court judge finds DeSisto School violated discovery orders.

Оригинальное название

Judge Order_DeSisto Case

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документA superior court judge finds DeSisto School violated discovery orders.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

5K просмотров13 страницJudge Order - DeSisto Case

Загружено:

Dave BiscobingA superior court judge finds DeSisto School violated discovery orders.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 13

Moriry

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

SUFFOLK, ss. SUPERIOR COURT

Civ. No. 01-5510 (E)

MASSACHUSETTS OFFICE FOR CHILD CARE SERVICES

Plaintiff :

oa

‘THE DESISTO SCHOOL, et al. .!

Defendants

MEMORANDUM OF DECISION AND ORDER

ON PLAINTIFFS MOTION FOR CONTEMPT

"AND FOR FURTHER EQUITABLE RELIEF

On December 6, 2001, this Court (Volterra, J.) issued preliminary injunction against

defendants prohibiting them from engaging in certain practices as well as imposing upon them

certain affirmative obligations. On March 13, 2002, plaintiff, the Office for Child Care Services

(“OCCS") filed a Complaint for Contempt, alleging that the defendants had violated the Court's

order in several important respects. Plaintiff also filed a Motion for Further Equitable Relief. Both

parties have submitted voluminous affidavits, and further evidence was presented at a hearing on

plaintiffs requests on March 29, 2002, For the following reasons, Iconelude that defendants have

violated this Court's orders and that the further equitable reliefrequested by plaintiffs appropriate,

Procedural Background

This litigation began at the administrative level almost two years ago. Because the

procedural history of this case provides a context for this Court's decision, a brief review of that

'Michael DeSisto.

history is in order.

jes must have a license from OCCS in

‘Massachiusetts law tequires that all group care faci

ordero operate. G.L.c.28A §1. A private residential school with 30 percent ofits students having

special needs is, pursuant to OCCS regulations, a group care facility requiring a license. 102

CMR. §3.02. The DeSisto School (the “Schoo!”), located in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, had

previously been licensed with OCCS but in 1986, itrepresented to OCS that its student population

no longer met the regulatory threshold and that the School therefore was outside OCCS" licensing

jurisdiction. OCCS subsequently received information, however, that, cBntrary to the School's

representations, many students did fit the criteria for being special needs children and, more

significantly, that the School's staff was engaged in abusive and dangerous practices. After

informal attempts to work with the School failed, OCCS in May 2000 filed a “show cause” notice

requiring that the School either demonstrate that it did not meet the regulatory criteria or submit an

application for ticense-within-30-daysAsit tamed-out;it.was-notuntil Mareh15,2002—the day————_—

after plaintiff filed a Complaint for Contempt in the instant case ~ that an application was finally

filed

‘On June 8, 2000, the School filed its response to the notice to show cause, demanding a

hearing and maintaining that less than 30 percent of its student population fit the definition of

special needs children. This position is in marked contrast to its position today where it has

highlighted the special needs of its students in defense of the practices that OCCS- challenges, and

in its assertion that any interruption in care could have devastating effects on the students

themselves. ? During the discovery process leading up to the administrative hearing, the School

repeatedly withheld records ind information from OCS, resulting in legal wrangling which delayed

a hearing fot more than a year. The OCCS sought and obtained a protective order; the School’s

noncompliance with that order ultimately resulted in sanctions. That same pattern of noncompliance

and noncooperation, delay and obstruction by the School and its representatives has continued

‘unabated up until the present.

Following the imposition of sanctions, a heating officer on September 5, 2001 determined

that the School was subject to OCS licensing requirements; her decision was affirmed by the OCCS

Commissioner on October 11,2001. The decision ordered that the School “immediately commence

thonecessary procedures” to secure alicense or cease operations. Rather than comply with the order,

the School chose once again to resort to the legal process: it filed suit in Superior Court seeking a

stay of the decision pending an appeal pursuant to G-L.c. 30A. DeSisto School, Ine. v, Office of

Chile Care Services; Ci¥-No- 01-4686, Om October 18; 20015 thi rat)-denied-the=

request for a stay, concluding that the School “has failed to demonstrate success on the merits” and

stating further that the subrhissions by OCCS showed that “the public interest will be harmed by

delay.” When OCCS representatives went to the School to begin the licensing process on October

22, 2001, however, they were denied access, precipitating a Complaint for Contempt. Again,

court order was necessary before OCCS could get access.

Ultimately, the School filed a Stipulation of Dismissel, with prejudice, of its 30A appeal.

2For example, in its opposition to the plaintiff's requests now before the Court, the

defendants describe themselves as “providing therapeutic and educational services to a

population of young people so troubled that they have been rejected by every other program in

Which they have been enrolled.” See p. 3 of Opposition to Plaintiff's Emergency Motion for

Equitable Relief. The students have been described in defendants? submissions to this Court as

suicidal, drug addicted, and suffering from various behavioral disorders.

Defense counsel contends that this was intended asa gesture of cooperation. Itisclear to this Court,

however, that (as Judge Volterra had already determined) the 30A appeal had little chance of

succeeding. The lawsuit did have the effect of buying more time for the School: technically, the

license application was not due until 30 days after the Stipulation of Dismissal was filed~on March

15, 2002.— almost two years after the administrative proceedings were instituted.

In the meantime, QCCS decided to initiate its own lawsuit and filed the instant case, seeking

affirmative equitable relief against both the School and its administrator Michael DeSisto. In

inary injunction, OCS filed affidavits By licensors describing

support of its request for a pre

overcrowding at the School, understaffing, physical facilities which did not comply with fire and

building codes, and certain practices by the staff toward children which the licensors considered to

bbe dangerous and overly punitive. Those practices included: strip searching of students; improper

restraints of children by untrained staff and even by other students; the separation and isolation of

a.child fiom the group for prolonged-periods;-withholding of food-as-panishment-anerestrietions———

on visitation and telephone contact with family members. On December 6, 2001, this Court

(Volterra, J.) granted most of the relief that OCCS had requested, concluding that it had areasonable

tional and dit

inary policies were in violation

likelihood of demonstrating that the School's edu

of OCS regulations. This Order is the subject of the Complaint for Contempt.

‘As OCS representatives went about the task of implementing the Order, the defendants

moved aggressively on the legal front: they filed a motion to “clarify or modify” the preliminary

ist OCCS,

("); filed a five-count counterclaim aga

injunction (which was denied, es “without me

alleging various violations of their state and federal constitutional rights (which has since been

dismissed by this Court) ; moved to take the deposition of OCCS? general cotunsel (a request which,

‘was quashed); and refused to produce Michael DeSisto for deposition in Boston (this Court ordered

Desisto to be produced). Finally, on March 13, 2002, OCS filed this Complaint for Contempt and

@ Motion for Further Equitable Relief. Now the defendants contend that they want nothing more

than to work cooperatively with OCS, and argue that the plainfff’s requests are unnecessary

because of the defendants” desire to voluntarily comply. In light ofthe above, this Court finds these

representations difficult to accept.

Facts,

‘The Complaint for Contempt alleges four broad ‘categories of violations: !)defendants?

policies and practices regarding restraints; 2) the condition of the physical facilities; 3) the practice

of prolonged separation and isolation of students without clinical approval; and 4) restrictions on

contact between students and family members. Where the competing affidavits are in stark conflict

on a particular issues, I make no fact findings. Rather, the following findings are based on facts

which are either not in dispute or which are based on the defendants’ own statements or submissions.

4 Restraints — 7 —

Faced with affidavits showing the improper use of restraints against students as well OCS’

‘expressed concem that such practices were dangerous to the physical well-being of students, Judge

‘Volterra ordered the defendants (among other things): a) to refrain from using restraints unless there

is a “clear danger to the student or others of physical harm;” b) to submit written reports to OCCS

on restraints which were used within 24 hours of the occurrence; c) to publish and implement an

OCCS approved restraint policy. I find that the defendants have violated each of these orders.

Defendants concede that no written reports were submitted to OCS until March 26, 2002,

some three months after Judge Volterra’s decision and just thiee days before the hearing on the

Contempt Complaint. Defendants attribute this to a “breakdown in communications.” Once the

reports were submitted (some of them dating back to December 2001), they showed thet staff

continued to use restraints in situations where there was no clear danger or in ways which would

appear to be improper and even dangerous to the physical well-being of the student. For example,

on March 22, 2002, a student was restrained for two hours for refusing to remove his hat; the staff

‘member engaged in restraining him threatened to “punch [the child’s] teeth right down his throat.”

On February 28, 2002, a report showed that a student threw up three times while being restrained.

Inan incident occurring on January 7, 2002, a student hit his face on the floor while being restrained,

injuring himself such that the nurse suggested he be sent to the hospital,

Finally, no written policy concerning restraints was submitted to OCCS until a week ago,

and what was submitted consisted of a single sentence. Such policies are usually quite lengthy, and

are important guides not only to staff designated to employ restraints but to the families whose

whether a facility's

children may be subject to them. They are also used by OCCS to dete

practices are in conformity with OCCS regulations and to monitor continuing compliance. The one

———xentence pioliey-submitted-by the School-was-the-seme-as-submitting-no-poliey-atall—

2. Separation of Students

In its original request for equitable relief, OCCS described a practice used by School staff

called “comering” whereby a student would be separated from the group and required to face a wall

for prolonged periods of time. Accordingly, Judge Volterra ordered that the school not separate

students from the group for more than 30 minutes at a time without the written approval of

clinician specifying the need for proloiged separation. Despite this order, the submissions before

the Court show that the practice of prolonged separation of students continues. Moreover,

defendants concede that, until recently, those designated to approve such separations were not

clinicians, even though the practice of separating students (now called “renewal”) is still occurring.

Defense counsel attributed this failure to obtain a clinician's approval to a misunderstanding of the

Court’s order. There is no licensed clinician currently on School staff.

3. Physical

ci

Judge Volterra also ordered that certain practices be halted at the School which placed it in

violation of the fire code and applicable OCCS regulations regarding the physical plants. Some of

those practices have indeed halted: for example, the number of students residing in adormitory room

has been reduced from as many as five to two, with each student provided with a bed and mattre

‘The practice of blocking dormitory room doors or barricading windows has ceased. However, the

School continues to be in violation of building code requirements and was described by a local

building inspector as recently as the hearing date as “dangerous to life and limb.” There are no

certificates of occupancy for three of the buildings on the School site. As of March 29, 2002, the

School had not complied with Orders issued by the Town of Stockbridge building inspector six

weeks before.

4. Restrictions on Student Contacts with Family. =

‘When it filed its initial request for injunctive relief, OCCS presented evidence showing that

students were essentially cut off from their families, some for as long as two years. In response to

this evidence, Judge Volterra ordered that the School not restrict visitations with family members

unless such restrictions are imposed by a court or are documented for therapeutic purposes in a

studént’s service plan, He also ordered the defendant’ to permit each student three outgoing

unmonitoted phone calls.a week to family. Nevertheless, the restrictions on family contact continue.

For example, only five students of the ninety at the School went home for Christmas holidays. And

although the School pays lip service to permitting telephone calls, there is ample evidence before the

Court that there is no real compliance with the Court’s order in this regard.

For example, there is evidence that the parent groups for which Michael DeSisto is School

liaison have agreed that any parent who accepts charges on more than one call from his child a

‘week will be “expelled” from the group. According to a student at the School, the School's director

Frank MeNear announced on December. 27, 2001 that parents would not accept more than one

telephone call a week so that the students “might as well not try to call them.” Its school policy

to prohibit students on the “farm” (described as a “relationship intensive” dormitory) from making

any calls to their parents. Finally, although the School was ordered to submit to OCCS written

policies and procedures for visitation and communication, no such policies have been submitted to

date :

3. Additional Facts relating to Motion for Further Equitable Relief

In the submissions before me, OCS presents evidence as to matters which are not the

subject of Judge Volterra’s order but are nevertheless relevant to the request for interim relief.

Although the some of these facts are disputed by the School, I nevertheless consider the evidence

whic OCES haspresented in-dctermining th fanthrerrelist- tional fac

as follows:

a, Staffing: OCS regulations require a student-to-staff ratio of 1 to 5 for a school of 90

children. Based on the evidence made available to the OCCS to date, the School does not have

‘enough staff to meet this ratio. Moreover, even though the Judge Volterra’s order required that

criminal background checks be performed on all staff members, the School has yet to provide

documentation that those checks have all been performed. Although Judge Volterra ordered the

School to train and certify staff in CPR and First Aid, OCCS has not provided proof of such training

and certification.

». Education: Bven though the School concededly accepts students with learning disabilities,

the documentation provided to OCCS thus far raises serous questions as to whether the Schoo! is

complying with applicable law. ' For example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

;poses certain requirements on the School any time it takes a child out of the classroom for more

than 10days, ‘There is evidence that the School has violated this requirement by removing children

from theireducational programs (through practices called “comering” and ‘“farming”) for prolonged

periods of time.? The School has failed to provide documentation that its teachers are certified, and

financial records show no, payment for special education consultants for the last two years.

Discussion

Inconsidering the request that the defendants be found in contempt of this Court’s December

6, 2001 Order, I apply certain well-established legal principles. To constitute civil contempt, @

party's conduct must be in clear disobedience of “clear and unequivocal demand.” Allen v. School

Committee of Boston, 400 Mass: 193, 194 (1987). Despite defendants’ assertions to the contrary,

Judge Volterra’s order was quite clear and quite specific. Although the order itself did not specify

_an-exact deadline, the request for a preliminary injunction, which the Court allowed in all important

respects, asked for compliance as to some matters within 45 days, and as to others, asked that the

defendants be ordered to comply immediately. A fair reading of the Order was that Judge Volterra

expected the School to act without delay and certainly no later than the deadlines set forth in the

Motion itself

‘The fact findings set forth above support the conclusion that the defendants have not

complied with this Court's orders. That the School has made some attempts to, comply with some

portions of the order is no excuse for continued non compliance with other provisions of that same

order. Moreover, those violations are not as to minor matters, but go the heart of the order itself.

>This failure to comply with legat requirements was one of the reasons the New

Hampshire Department of Education determined that the School was not an appropriate

placement for a student who had been "comered” for more than seven weeks.

‘Although a fine would not be appropriate absent some evidence that the amount reflected

actual losses suffered as ‘a result of the violation, see eg. Manchester v. Department of

Environmental Quality Engineering, 381 Mass. 208,211 (1980), this Court doeshave the diseretion

torequire that thecontumacious party pay thereasonable attorney's fees of the party forced to bring

the contempt complaint. See e.g. Police Commissioner v. Gows, 429 Mass. 14 (1999) and citations

contained therein, Although such discretion should be exercised sparingly, the Court concludes that

the instant case is precisely the kind of case where such a sanction would be appropriate, Rather than

work with OCS, the defendants have used the legal process to obstruct ahd delay. Rather than

come into voluntary compliance, the defendants have repeatedly required OCCS to assumed the

burden of obtaining judicial assistance. Even after court orders have entered, defendants have not

complied ~or they liave come isto compliance only after OCCS has filed a complaint for contempt.

‘There must be some cost for such conduct.

‘As-to-the Motion-for Further Equitable Relief;-this-Court applies—the-stondazds.setforthin.

Packaging Industries v. Cheney, 380 Mass. 609, 616-617 (1990). An injunction should not issue

unless the moving party demonstrates, first of all, that it has a reasonable likelihood of suecess on

the merits. Secorid, plaintiff must demonstrate a substantial risk of irreparable harmif the relief were

not granted , which harm. is greater than any similar risk created for the opposing party if the

injunction were to issue, Finally, this Court considers the public interest at stake here. See

Commonwealth v. Mass.CRINC, Inc. 392 Mass. 79, 89 (1984). Indeed, this is perhaps the most

{impottant consideration: “when the government acts to enforcea statute or make effective a declared

policy of [the Legislature], the standard of public interest and not the requirements of private

litigation measure the propriety and need for injunctive relief.” Ibid.

Applying these principles to the instant case, I conclude that OCS is entitled to the relief

it has requested. Specifically, I conclude that OCCS has demonstrated a likelihood that it will

succeed on the merits of its claim that the Schoo] isin violation of OCCS regulations and applicable

law, Indeed, my findings with respect to the Contempt Complaint compel this conclusion. Further,

there is a risk of irreparable harm if the request is not allowed. As the School itself concedes, its

students are extremely vulnerable psychologically and many of them have special educational needs.

Improper practices by untrained staff could have potentially grave consequences for these students.

Finally, there is a substantial public interest in the School’s complying with the requirements which

OCCS, through its licensing authority, is charged with enforcing, Afterall, these requirements were

ildren whom the School serves.

formulated to protect precisely the kind of ¢

‘This Court also considers the tortured procedural history in this case in adopting the relief

thatit does, Defendants have made it quite apparent that they will not comply with OCCS requests

‘without a clear court order to do so. It is therefore most appropriate that this Court impose firm

————sdeaillines,-swith-specifie- consequences for-non-complianceDefendants have offered by wayof —__

ide which they say that OCCS licensors have

excuse for their noncompliance the hostile atti

adopted, resulting in misunderstandings and breakdowns in communication. That is all the more

reason why someone from outside OCCS (but meeting with OCCS? approval) should become

involved, at the School's expense, in order to facilitate the licensing process.

Conclusion and Order

Accordingly, for all the foregoing reasons, this Court hereby finds the defendants in

Contempt this Court’s order of December 6, 2001 and hereby ORDERS that the defendants pay all

the costs, including reasonable attorney's fees, incurred by OCCS in bringing the Contempt

Complaint. OCCS will submit a request for a specific amount, substantiated by affidavit, within

10 days of this Order. Any opposition will be filed within 10 days of defendants’ receipt of OCCS's

request, and this Court will make a decision based on those submissions.

OCCS? Motion for Further Equitable Relief is ALLOWED and it is hereby. ORDERED

that:

1. Effective immediately, the School shall not enroll any new student until such time as the

defendants produce documentation, satisfactory to occs, that the School has hired, scheduled and

trained a sufficient number of staff to care for the students currently enrolled at the School.

2. Within two weeks of the date of this Order, the School must hire an OCCS-approved

consultant to work on developing the following policies for OCCS approval and implementation:

behavior management, including restraint policy; visiting, mail and telephone use; staff orientation

and training, In addition the School shall work with the consultant on developing treatment plans

for students and on writing incident reports

3, Effectively immediately, the School must complete restraint reports and send the incident

reports to OCCS within 24 hours of the restraint,

4, By June 15, 2002, DeSisto must have fully implemented the following policies as

approved by OCCS: education; behavior management, including restraint; visits, mail and

telephone; staff orientation and training. In addition DeSisto must have obteined all inspections,

permits, certificates, and reports as required by 102 C.M.R. §3.08(1) (a) (b) and (¢), Failure to meet

any of these requirements by June 15, 2002 will result in the immediate closure of the School

5, By September 3, 2002, the School must be in full compliance with OCCS regulations and

policies or immediately close the School to all students until such time as OCCS determines that

there has been full and complete compliance.

Dated: April 8, 2002

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Anonymous LTR 9-18-17 REDACTED 11-3-17Документ5 страницAnonymous LTR 9-18-17 REDACTED 11-3-17Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Notice of Claim Filed Against Buckeye PDДокумент32 страницыNotice of Claim Filed Against Buckeye PDDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Grossman Performance Improvement PlanДокумент4 страницыGrossman Performance Improvement PlanDave Biscobing100% (1)

- Seth AnswerДокумент27 страницSeth AnswerDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Chief Hall HighlightsДокумент4 страницыChief Hall HighlightsDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- McGregor Berch ContractДокумент4 страницыMcGregor Berch ContractDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Ducey Letter - Aug12018Документ1 страницаDucey Letter - Aug12018Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Bidwill Letter Sept26Документ1 страницаBidwill Letter Sept26Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Gov. Ducey Letter To Dental BoardДокумент1 страницаGov. Ducey Letter To Dental BoardDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- JCCR Approves Lock FundingДокумент67 страницJCCR Approves Lock FundingDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Buckeye Police Department Citizen RegistryДокумент5 страницBuckeye Police Department Citizen RegistryDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Cardena ArrestДокумент3 страницыCardena ArrestDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- NV AG InterveneДокумент15 страницNV AG InterveneKean BaumanОценок пока нет

- Nevada Lawsuit Mentions ABC15 ReportДокумент32 страницыNevada Lawsuit Mentions ABC15 ReportDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Calls For ServiceДокумент7 страницCalls For ServiceDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Yeagley ArrestДокумент2 страницыYeagley ArrestDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Dps Draft WWD Lesson Plan Sep 2015Документ10 страницDps Draft WWD Lesson Plan Sep 2015Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Wrong Way Committee Meeting 6-12-14Документ1 страницаWrong Way Committee Meeting 6-12-14Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Date: TO: From: Subject: Wrong Way Drivers Committee For:: ST-MENDOZA001990Документ2 страницыDate: TO: From: Subject: Wrong Way Drivers Committee For:: ST-MENDOZA001990Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Wrong Way Committee Meeting 6-27-13Документ1 страницаWrong Way Committee Meeting 6-27-13Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Pomeranz 22405015Документ4 страницыPomeranz 22405015Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Cosmetology Letter and Report Sept. 21, 2017Документ8 страницCosmetology Letter and Report Sept. 21, 2017Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

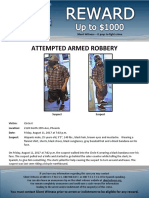

- 17-2553 Flyer - Att Armed Robbery CK 35th AveДокумент1 страница17-2553 Flyer - Att Armed Robbery CK 35th AveDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Dps Draft WWD PolicyДокумент2 страницыDps Draft WWD PolicyDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- NM ABQ Carton Recc 7 10 17Документ54 страницыNM ABQ Carton Recc 7 10 17Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Internal InvestigationДокумент15 страницInternal InvestigationDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- Litigation Management Services Funding AgreementДокумент7 страницLitigation Management Services Funding AgreementDave BiscobingОценок пока нет

- May 11 TranscriptДокумент149 страницMay 11 TranscriptDave Biscobing100% (1)

- NM ABQ Agreements Order 5 17 17Документ25 страницNM ABQ Agreements Order 5 17 17Dave BiscobingОценок пока нет