Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Lapindo Mudflow Disaster - Environmental, Infrastructure and Economic Impact

Загружено:

ArianiОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Lapindo Mudflow Disaster - Environmental, Infrastructure and Economic Impact

Загружено:

ArianiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network]

On: 8 September 2009

Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 782980718]

Publisher Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713406865

The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic

impact

Heath McMichael a

a

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra

Online Publication Date: 01 April 2009

To cite this Article McMichael, Heath(2009)'The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic impact',Bulletin

of Indonesian Economic Studies,45:1,73 83

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00074910902836189

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910902836189

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or

systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or

distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents

will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses

should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,

actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly

or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2009: 7383

THE LAPINDO MUDFLOW DISASTER: ENVIRONMENTAL,

INFRASTRUCTURE AND ECONOMIC IMPACT

Heath McMichael*

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra

This note examines the environmental, infrastructure and economic impact of the

Lapindo mudflow disaster in East Java province. It outlines unsuccessful attempts

to staunch the mud volcano, concerns for human health and plans for long-term

management of the mudflow. It considers the impact on transport and logistics networks and the additional costs to the East Java economy. The heaviest economic

impact has occurred in the region surrounding the mud volcano in Sidoarjo district, but areas to the east and west are also affected. Individual firms in East Java

have found means of accommodating their business operations to the mudflow

with some provincial government assistance. PT Lapindo Brantas, the company

considered responsible for the drilling that led to the mud volcano, has been slow

in compensating victims as required by presidential decrees. Delays in finalising

compensation appear to be holding back implementation by the national government of critical infrastructure reconstruction work.

On 29 May 2006, mud and gases began erupting unexpectedly from a vent 150

metres from a hydrocarbon exploration well near Sidoarjo in East Java. The flow

of mud has continued since then at rates as high as 160,000 cubic metres per

day. Dubbed the Lapindo mudflow after the company responsible for drilling

the well, the mud volcano has inundated an area in excess of 6.5 square kilometres, despite attempts to contain it by constructing a series of embankments.1 The

mudflow has inundated factories, farmland and the SurabayaGempol toll road

in the sub-district of Porong. It has placed at risk a water pipeline connecting

Surabaya with the Umbulan spring near Pasuruan, as well as fibre-optic cables

carrying broadband data from Surabaya to Kupang in Eastern Indonesia. A gas

pipeline near the site ruptured and exploded in November 2006, reducing the

* The views expressed in this note are the authors alone and have no official status or

endorsement. They are based on material from public sources and fieldwork conducted

during private visits to Surabaya in June 2007 and to Jakarta and East Java in August

September 2008.

1 The eruption site is also called the Lusi mud volcano, from the initial syllables of lumpur

(mud) and Sidoarjo (the main location of the mudflow). There are numerous scientific overviews of the site and discussions of the eruption, including those by Cyranowski

(2007); Mazzini et al. (2007); and Davies et al. (2007).

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/09/010073-11

DOI: 10.1080/00074910902836189

2009 Indonesia Project ANU

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

74

Heath McMichael

supply of gas for fertiliser production; this has in turn led to local fertiliser shortages (Plumlee et al. 2008: 12).

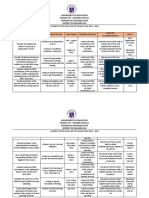

Around its centre in Sidoarjo district, the effects of the mud volcano have been

particularly devastating (figure 1). Mud flowing from the volcano has displaced

over 30,000 people in more than a dozen villages, severely disrupting their livelihoods. The local property market has collapsed: residents are unable to obtain

valuations on their properties, which are considered unbankable. New mud and

gas fissures continue to emerge. It is unclear whether a mud eruption in March

2008 next to an ammonia condensation plant about three kilometres from the

main eruption vent in the village of Siring is a stand-alone event or the harbinger

of heightened mud volcano activity (BPLS 2008). While the impact of the mudflow has been felt most acutely by the local community in Sidoarjo, other regions

in East Java have experienced environmental, logistical and economic effects as a

consequence of the disaster.

The dangers of drilling for oil and gas in the Sidoarjo area have been known for

generations. According to a former senior East Java civil servant, Dutch colonial

archives from 1910 show that the area around Porong sub-district was considered

prone to gas eruptions.2 American oil exploration companies in East Java in the

1950s were also aware of the areas unstable geological nature.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

The accumulation of mud from the original vent is accompanied by subsidence

in the surrounding area. It has been projected that more than 30 metres of subsidence will occur in the next few years within several kilometres of the eruption

vent. The possibility exists that a huge crater will form from the hollowed-out

remains of the mud volcano. Dried mud deposits could have adverse effects on

river and marine environments and on the health of local residents (Plumlee et

al. 2008: 2).

Another cause for concern is the muds impact on natural drainage patterns in the Brantas River basin. Mud-induced siltation of the Porong River is

expected to heighten the risk of wet-season flooding in the vicinity of Mojokerto

and Sidoarjo. If flood-waters cannot be contained upstream, it is feared the Surabaya River will overflow, leading to possible widespread flooding in Surabaya

(Rumiati 2007: 412).

Evidence is mounting that the mud has a harmful impact on river ecosystems

and human health. The mud has been assessed as containing phenol in concentrations exceeding the maximum residue limit (Friends of the Earth International

2007: 5).3 Phenol is toxic to fish, aquatic vegetation and humans. A recent report

by the United States Geological Service has found that several elements, notably

arsenic, are present in concentrations that exceed US government environmental

guidelines for residential soil (Plumlee et al. 2008: 89). It can be assumed that

2 Interview with Mr Soedarman, former Chair, East Java Investment Board, Surabaya,

6 June 2007.

3 The maximum residue limit as here defined refers to the maximum concentration of

chemical residue allowable by regulation to occur in a particular substance (in this case,

the Lapindo mud).

The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic impact

75

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

FIGURE 1 Map of Mudflow Area and Surrounding Region

the mud will seriously affect the livelihoods and health of shrimp and fishing

communities located adjacent to the Porong River and the Madura Strait, that is,

communities in the districts of Sidoarjo, Madura, Pasuruan and Probolinggo (to

the east of the map area), and the municipality of Surabaya.

With attempts to staunch the flow apparently unsuccessful, attention has turned

to developing a plan for its long-term management. A draft United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) evaluation in June 2008 identified three mitigation

options: pumping the mud directly into the sea (at a cost of Rp 13 trillion over 30

years); pumping the mud to mangrove wetlands to the east while diverting the

Porong River (at a cost of Rp 16 trillion over 30 years); and, most expensively,

constructing an open channel to allow mud to flow directly to the sea (a one-off

cost of Rp 33 trillion) (UNEP 2008: 7680). None of these options is risk-free: with

the first, there is concern that pumping would not be able to move the required

76

Heath McMichael

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

volume of viscous mud; the second increases the risk of flooding; and the third

would impinge on production in farming and aquaculture areas.

IMPACT ON TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS NETWORKS

It is estimated that before the mudflow the SurabayaGempol toll road accommodated 20,00030,000 vehicles per day, including up to 3,000 container vehicles

(Yahya 2007). The cutting of the road has heightened congestion on secondary

roads to the east and west of the market at Porong and on arterial roads through

the centres of Krian, Mojokerto and Mojosari to the west. As a result, the flow of

goods and people from Surabaya to the city of Malang and to regions to the east

and south of Malang has been disrupted. Transportation times have increased for

freight from Malang, Gempol and nearby Pandaan and from Pasuruan bound

for Tanjung Perak port at Surabaya. According to a foreign joint venture clothing

manufacturer in Probolinggo, road congestion has increased trucking times to

Surabaya from four hours before the mudflow to around 10 hours. Up to an extra

day is now spent exporting finished product through the port and a further additional day is spent bringing material inputs to the factory.4

The additional time needed to transport goods to port or obtain deliveries of

locally sourced materials implies a considerable financial burden for many companies in terms of the extra fuel used, the overtime paid to trucking operators

and the requirement to pay illegal levies for the use of secondary roads. For some

shippers, late delivery of goods to the container terminal at Surabaya has incurred

additional demurrage costs of up to Rp 600,000 per container. It has been estimated that the mudflow has, on average, increased transport costs for individual

manufacturers by 30%, and one Sidoarjo-based housing tile manufacturer claims

that costs have increased by 5060% for its raw materials sourced from the Malang

region.5

The existing single rail line between Surabaya and Malang traverses the foot of

the mudflows western embankment and is at risk of being washed away should

the embankment be breached. Alternative corridors to Malang through Kertosono,

Kediri and Blitar to the west and south-west are circuitous, and their use would

add considerably to rail freight times to and from Surabaya.

IMPACT ON THE ECONOMY AND BUSINESS SECTOR

The mudflow has had a marked impact on the provinces economy and business

sector. Using inputoutput analysis based on data from the central statistics agency

(BPS) and interviews with industry associations, researchers at the Surabaya Institute of Technology (ITS), in collaboration with the Indonesian Environment Ministry, estimate the total cost of the mudflow through August 2007 to be in the order

of Rp 28.3 trillion (Rumiati 2007: 3670). This figure comprises Rp 8.3 trillion in

infrastructure asset losses, Rp 5.8 trillion in lost production in Sidoarjo district, and

Rp 14.2 trillion in indirect losses to the provincial economy, especially in food and

4 Interview with Mr Joseph Chan, PT Eratex Jaya, Surabaya, 7 June 2007.

5 Interview with Mr Sam Santoso, PT Kuda Laut, Surabaya, 13 August 2008.

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic impact

77

leather processing, transport and the hospitality industry. Notwithstanding the

difficulty of relating these losses to provincial GDP, the ITSEnvironment Ministry

report suggests that the East Java economy may have contracted by 4.2% between

May 2006 and August 2007 (Rumiati 2007: 467). The scale of economic loss is

borne out elsewhere: according to the author of an unpublished appraisal by the

Supreme Audit Agency (BPK) in 2007, estimated total direct and indirect costs of

the mudflow in its first year were around Rp 30 trillion.6 In any event, the economic

costs generated by the mudflow are likely to continue to grow substantially.

The economic impact of the mudflow is unevenly spread through the province.

The region suffering the biggest loss is the central corridor from Surabaya south

to Malang, which constitutes East Javas manufacturing heartland (Santosa and

McMichael 2004: 14). This region, known as the pita pembangunan (growth ribbon) of East Java comprises the districts of Sidoarjo, Mojokerto, Pasuruan and

Malang.

In Sidoarjo, the mudflow has had a direct impact, with economic growth in the

district falling from 6.7% in 2005 to 4.6% in 2006 (Badan Pusat Statistik Propinsi

Jawa Timur 2007: 41). The leather processing, food, and hotels and restaurants

sectors have been most affected. In Tanggulangin sub-district, it is estimated that

output from the flourishing leather industry dropped by 80% after the appearance of the mud volcano.7 The mudflow has undermined Sidoarjos ranking as

an exemplar of economic growth and public service (Setiadi 2007: 247). Given

that 2030% of East Javas exports and imports originate in, or are destined for,

factories in Sidoarjo, the likelihood that the districts economy will remain weak

for some time is of particular concern (Yahya 2007).

The economy of the Malang district has also been hard hit by the effects of the

mudflow. Growth in the furniture sector declined from 7.2% in 2005 to 5.3% in 2006

(Ananda 2007). Hotels in tourist centres in Malang and in Trawas and Prigen on

the northern slopes of Mt Arjuna experienced declines of up to 80% in occupancy

rates at the onset of the mudflow, but appear to have recovered somewhat since

then. Surabaya trucking firms and kretek (clove) cigarette manufacturers in the

Malang area have been particularly affected by disrupted distribution channels.8

The downturn in the handicraft industry has transferred Malangs competitive

advantage in that sector to neighbouring Tulungagung, a traditional competitor

of Malang.9

Regions to the west of the central corridor have been affected by the infrastructure and transport bottleneck around Surabaya that resulted from the mudflow.

According to an independent research institute associated with the economics

faculty of Airlangga University, increasing volumes of manufactures from the

western districts of Jombang, Kediri and Tulungagung, which are destined for

inter-island or international markets, are being exported via Semarang in Central

Java. However districts to the north-west of SurabayaGresik, Lamongan, Tuban

6 Interview with Dr Candra Fajri Ananda, Brawijaya University, Malang, 16 August 2008.

7 Interview with Dr Kacung Marijan, Airlangga University, Surabaya, 14 August 2008.

8 Interview with Mr Olivier Bernard, PT Tripper Nature, Jakarta, 11 September 2008.

9 Interview with Dr Bambang-Heru Santosa, Central Statistics Agency, Jakarta, 9 August

2008.

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

78

Heath McMichael

and Bojonegorodo not appear to show any negative effect from the mudflow.

This region is experiencing a mini economic boom owing to the emergence of

new industries servicing oil and gas projects, such as the Cepu oilfield development in Bojonegoro. The Lamongan Shore Base, a multi-million dollar joint

venture between an East Java-owned corporation, PT Wira Jatim, and a Singapore

logistics firm, has been established to service oil and gas projects in eastern Indonesia. The facility, located on the north coast near Lamongan, includes a dry dock

and bonded warehouse.10

In East Javas eastern regions the picture is also mixed. In Probolinggo district, the fish canning industry has suffered financial losses stemming from the

increased trucking distances required to transport goods to Surabaya. Similarly,

seafood exporters using cold storage facilities in Pasuruan district have had to

bear additional freight costs to move their product to the port of Surabaya for

export.11 By contrast, cane sugar production has been little affected, because of

that industrys reliance on local processing and distribution and the use of small

trucks to transport cane over secondary roads.12 Proposals by the East Java Chamber of Commerce and Industry to the provincial and national governments to

upgrade Tanjung Wangi port in Banyuwangi (on the eastern tip of Java) to enable

it to accommodate larger vessels for inter-island trade have not gained traction.

The chamber believes there is potential to expand Tanjung Wangi as a gateway for

the export of commodities from Jember (especially tobacco), Situbondo, Bondowoso and Banyuwangi districts.13

The degree to which the mudflow has affected individual manufacturing enterprises in East Java appears to be related to the scale of their logistics and distribution networks. Larger manufacturers with more diverse distribution networks

have been less disadvantaged than their small and medium enterprise counterparts. One of the jewels in the provinces economic crown is the kretek manufacturer, PT Gudang Garam. The company employs a workforce of 41,000 in Kediri

and generates nearly a third of the districts local tax revenue. Gudang Garams

output and distribution has not been affected significantly by the mudflow. Notwithstanding the sudden death in July 2008 of the companys President Commissioner, Rachman Halim, who was the son of its founder, business confidence in

Kediri remains strong.

Individual firms have found means of accommodating their business operations to the difficult circumstances wrought by the mudflow. For example, the

bottled water manufacturer PT Ades Waters Indonesia, a subsidiary of PT Aqua

Golden Mississippi (Danone Group), sources its raw material from springs in

Pandaan and has relocated its packaging plant to Surabaya to reduce transport

costs. Leather handicraft companies from Tanggulangin village, situated near the

10 Interview with Mr Eugene Lim, PT Eastern Logistics, Lamongan, 3 June 2007.

11 Interview with Mr Johan Suryadarma, Indonesian Frozen Seafood Association, East

Java branch, Surabaya, 12 August 2008.

12 Interview with Mr Adig Suwandi, PT Perkebunan Nusantara XI (Persero), Surabaya,

2 September 2008.

13 Interview with Mr Erlangga Satriagung, East Java Chamber of Commerce and Industry,

Surabaya, 11 August 2008.

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic impact

79

source of the mudflow, have joined together to open exhibition halls in Surabaya

as a means of obviating the need for prospective buyers to travel to the mudaffected area. The East Java government has taken concrete measures to assist

industries affected by the mudflow, including the establishment of a new trade

centre in Mojokerto to showcase handicrafts and leather goods manufactured in

the Sidoarjo area.14

It should be recognised that, aside from the mud volcano, a wide range of factors have a bearing on the rate of economic growth in the province. For example, regulatory barriers to domestic trade in East Java are a significant obstacle

to business sector growth (World Bank and The Asia Foundation 2005: 10811).

Inadequate transport infrastructure (especially in the rail network), a chronic

shortage of reliable power for industry and rising electricity tariffs are acknowledged as impediments to domestic and foreign investment.15 Moreover, a lack

of clarity in government decision making with respect to mudflow compensation and reconstruction arrangements has had a negative impact on local business

confidence.16

THE GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

Since September 2006, when President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono declared a

400 hectare area in the Sidoarjo district a disaster area unfit for human habitation,

the national government has sought to mitigate the complex environmental and

social impact of the mudflow. So far, its efforts have achieved little in concrete

terms. On 16 October 2006, the president authorised mud to be pumped into the

Porong River. However, the viscosity of the mud, subsidence around the eruption

vent and a low gradient towards the sea approximately 20 kilometres to the east

rendered this containment strategy largely ineffective.

In April 2007, the president issued a decree (PP 14/2007) ordering the company

responsible for drilling the initial well, PT Lapindo Brantas, to compensate victims of four villages at the centre of the affected area. A further decree in July 2008

(PP 48/2008) provided for compensation for another three villages, bringing the

number of residents to be compensated to nearly 13,000 households. The decree

ordered Lapindo to pay compensation in two phases20% in the first phase and

80% in the secondto cover lease payments on new houses for the victims. By

mid-2007, the president had ordered Lapindo to pay Rp 4.35 trillion in compensation to victims and for efforts to halt the mudflow (Friends of the Earth International 2007: 7).

Compensation has been slow to reach the victims. In August 2008, the Minister

for Public Works said that the national government would allocate Rp 1.19 trillion in the 2009 budget to deal with the mudflow, including compensation for the

victims, but a finance ministry spokeswoman declared that government funding

14 Interview with Mr Kresnayana Yahya, Surabaya Institute of Technology, Surabaya,

15 August 2008.

15 Interview with Mr Djoni Irianto, East Java Investment Board, Surabaya, 12 August

2008.

16 Interview with Mr Erlangga Satriagung, East Java Chamber of Commerce and Industry,

Surabaya, 11 August 2008.

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

80

Heath McMichael

would only be disbursed once Lapindo had discharged its compensation obligations in full (JP, 12/9/2008). For its part, Lapindo asserted that it was fulfilling

its compensation obligations and had, by August 2008, paid victims 20% of their

entitlements (JP, 1/9/2008).

While Lapindo acknowledges its compensation obligations, it does not accept

responsibility for the initial eruption, claiming that scientific analysis (such as that

by Mazzini et al. 2007: 37588) shows that it was linked to tectonic activity after an

earthquake in Central Java two days earlier. This stance flies in the face of overwhelming scientific opinion that the initial mud eruption was caused by Lapindo

drilling.17 Lapindos tardiness in discharging its compensation obligations in full,

and the governments apparent unwillingness to force it to do so, have been the

cause of vocal frustration on the part of Sidoarjo residents (JP, 9/12/2008).

Large-scale infrastructure rehabilitation work by the national government has

not yet commenced. A recovery blueprint coordinated by the National Development Planning Agency, Bappenas, with input from national and provincial government agencies, academic institutions, foreign donors and UNEP, remains on

hold.18 The governments Sidoarjo Mudflow Handling Agency (BPLS) has identified a parcel of land 12 kilometres long and 120 metres wide to the west of the

mudflow, for new toll road, rail and gas pipeline infrastructure. However, BPLS

appears unwilling to use the governments power of eminent domain to purchase

the land.19 One explanation for the delay in starting reconstruction work is that

the the government believes the cost of relocating affected infrastructure should be

borne by Lapindo (Harsaputra 2006) as required in Presidential Decrees 14/2007

and 48/2008. Clearly, though, the huge cost of rehabilitation is beyond the capacity of the private sector alone to bear, and further delay in starting the reconstruction effort seems difficult to justify.

At provincial government level, the East Java Development Planning Agency

has proposed a new inter-modal transport hub and industrial estate at Tarik,

about 20 kilometres to the west of Porong. This so-called New Town will require

coordinated central, provincial and local government planning and extensive

land acquisition. Unfortunately, the history of land acquisition for infrastructure

works in East Java is replete with cases of speculative land deals concocted by

well-connected former public figures. A recent example was the negotiation of

land access to build Surabayas Juanda airport toll road, which took 10 years to

complete (Graham 2006).

Provincial planners are keen to obtain foreign assistance for mudflow mitigation, infrastructure and housing reconstruction work and efforts to restore

community livelihoods.20 The United States and Australian governments have

17 Geologists blame gas drilling for Indonesia mud disaster, source: Durham University,

<http://www.physorg.com/news144596883.html>, posted 30 October 2008.

18 Interview with Mr Suprayoga Hadi, Directorate for Disadvantaged Regions, Bappenas,

Jakarta, 4 August 2008.

19 For a discussion of the national governments powers of eminent domain, see McLeod

(2005: 1467).

20 Interview with Mr Hadi Prasetyo, East Java Development Planning Agency, Surabaya,

2 September 2008.

The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic impact

81

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

contributed technical expertise towards analyses of the geophysical aspects of the

mudflow, but it is unlikely that foreign donors will be willing to provide cash

grants or loans without an assurance that money will not fall into the hands of

land speculators.

THE POLITICS OF THE MUDFLOW

The company widely considered responsible for the mud volcano, PT Lapindo

Brantas, is a subsidiary of the Bakrie Group, which is indirectly owned by the

family of the Coordinating Minister for Peoples Welfare, Aburizal Bakrie.21 Until

very recently, Bakrie was reputed to be Indonesias richest man. He has a close

relationship with President Yudhoyono, having helped bankroll Yudhoyonos

presidential election campaign in 2004 (Latul 2008).

Bakrie is also believed to be close to Vice President Jusuf Kalla. During a collapse in the share price of the Bakrie Group mining subsidiary PT Bumi Resources

in November 2008, allegations of government favouritism arose over the suspension of trading in Bumi stocks (Hick 2008). Kalla reportedly claimed that the suspension of Bumi shares was necessary to prevent sharp falls in share prices and

ease market speculation [and to protect] the interests of investors, publicly listed

companies and the overall economy; he argued that suspending trade in company shares was common practice around the world (Simamora 2008).

These relationships complicate the governments handling of the mudflow

problem and appear to account for its reluctance to force Lapindo to expedite

compensation payments. In December 2008 it was reported that Lapindo had

reached a deal with mudflow victims to pay the remaining 80% of compensation through monthly instalments of Rp 30 million to each affected household

(Nurhayati 2008). State Secretary Hatta Rajasa claimed that since Lapindo had

been facing financial difficulties because of the global economic crisis, it would

be difficult for us to push for more than this (JP, 5/12/2008).

Lapindo is widely believed to be actively attempting to influence Indonesian

public opinion in favour of its position. The company has taken steps to ensure

that it has a voice through the media: in 2008 it bought the venerable local daily,

The Surabaya Post, and installed the companys spokesperson as its new chief

editor.

Lapindos efforts to mould public debate suffered a setback during campaigning for the East Java gubernatorial elections in June 2008. At a public forum in

Surabaya, two of the leading candidates for the position of governor, Khofifah

Parawansa, representing a coalition of parties headed by the United Development

Party, and Soekarwo, from the National Mandate Party (PAN), refrained from

apportioning blame for the disaster to Lapindo. However, the candidate from the

Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle, Sutjipto, openly accused Lapindo of

negligence leading to the initial mud volcano eruption (JP, 23/6/2008). Although

East Java law officers have been accused of being blinded by politics in failing to

prosecute the company for its actions (JP, 1/9/2008), the question of legal liability

21 See Friends of the Earth International (2007: 89) for an outline of PT Lapindos

relationship to the Bakrie Group.

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

82

Heath McMichael

should eventually be settled in the Supreme Court (Australian Financial Review,

15/9/2008).

To date, there has been minimal public commentary on the ethical and corporate responsibility aspects of the Lapindo disaster because of the sensitivity

surrounding the interests of the main players involved. However, continuation

of the mudflow, possibly for years to come, will attract increasing national and

international concern. Compensation is unlikely to be resolved soon: the Bakrie

Goups financial difficulties as a result of the downturn in global coal prices will

further delay finalisation of payments to the victims of the disaster (Asia Times

Online, 27/11/2008). Businesses faced with increased costs arising from the mudflow will be forced to rely on their own mettle until critical infrastructure rehabilitation and reconstruction work commences. The governments failure to deal

decisively with the disaster is likely to be a factor in voting in the April 2009 elections, particularly in East Java (Ashcroft and Cavanough 2008: 335).

REFERENCES

Ananda, C. (2007) Development and environment in East Java Province, in Empowering

Regional Economic Development toward Sustainable Poverty Alleviation, eds C.F. Ananda,

B.P. Resosudarmo and S. Nazara, Indonesian Regional Science Association, Jakarta.

Ashcroft, V. and Cavanough, D. (2008) Survey of recent developments, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 44 (3): 33563.

Badan Pusat Statistik Propinsi Jawa Timur (East Java Provincial Statistical Agency) (2007)

Produk Domestik Regional Bruto, Kabupaten/Kota se-Jawa Timur [Regional GDP, East Java

Districts/Municipalities], East Java Provincial Statistical Agency and East Java Provincial Development Planning Agency, Surabaya, November.

BPLS (Badan Penanggulangan Lumpur Sidoarjo, Sidoarjo Mudflow Handling Agency)

(2008) The Chronology of the Collapsed Water Reservoir Tower at PT Lion Steel, West

Siring Village, Unpublished report, BPLS, Surabaya.

Cyranowski, David (2007) Muddy waters: how did a mud volcano come to destroy an

Indonesian town?, Nature 45: 81214.

Davies, R.J., Swarbick, R.E., Evans, R.J. and Huuse, M. (2007) Birth of a mud volcano: East

Java, 29 May 2006, GSA Today 17 (2): 49.

Friends of the Earth International (2007) Lapindo Brantas and the mud volcano, Sidoarjo,

Indonesia, June, Background paper, accessed 5 January 2009 at <http://www.

foeeurope.org/publications/2007/LB_mud_volcano_Indonesia.pdf>.

Graham, D. (2006) Surabayas new airport: no speedy access, Indonesia Now with Duncan

Graham blogspot, <http://indonesianow.blogspot.com/2006/03/juanda-surabaya.

html>, posted Friday 10 March.

Harsaputra, I. (2006) Lapindo again ordered to pay up, Jakarta Post, 29 December.

Hick, J. (2008) Bakrie looks exposed in meltdown, Asia Times Online, posted at

<http://www.atimes.com/atimes/archive/11_27_2008.html>, 27 November 2008.

Latul, J. (2008) The Bakrie empire and Indonesias government, posted at <http://www.

asiasentinel.com>, 25 December.

Mazzini, A., Svensen, H., Akhmanov, G.G., Aloisi, G., Planke, S., Malthe-Srenssen, A. and

Istadi, B. (2007) Triggering and dynamic evolution of the LUSI mud volcano, Indonesia, Earth and Planetary Science Letters 261 (34): 37588.

McLeod, R. (2005) Survey of recent developments, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

41 (2): 13357.

Nurhayati, Desy (2008) Mudflow victims, govt agree to settle compensation, Jakarta Post,

12 March.

Downloaded By: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] At: 21:02 8 September 2009

The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic impact

83

Plumlee, G.S., Casadevall, T.J., Wibowo, H.T., Rosenbauer, R.J., Johnson, C.A., Breit, G.N.,

Lowers, H.A., Wolf, R.E., Hageman, P.L., Goldstein, H., Anthony, M.W., Berry, C.J., Fey,

D.L., Meeker, G.P. and Morman, S.A. (2008) Preliminary analytical results for a mud

sample collected from the LUSI mud volcano, Sidoarjo, East Java, Indonesia, US Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1019, USGS, Reston VA.

Rumiati, T. (2007) Analisa resiko terhadap hasil prediksi aspek teknis 5 tahun [Risk analysis of technical aspects of 5-year prediction results], in Analisis Resiko Bencana Lumpur

Porong, Skala Lokal Sidoarjo dan Skala Regional Jawa Timur [Porong Mud Disaster Risk

Analysis, Sidoarjo Local and East Java Regional Scale], Report published by the Department of the Environment and the Surabaya Institute of Technology, Surabaya, August.

Santosa, Bambang-Heru and McMichael, Heath (2004) Industrial development in East

Java: a special case?, Working Papers in Trade and Development No. 2004-07, Arndt

Corden Division of Economics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, College of

Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, November.

Setiadi, R. (2007) Memantau daerah menyemai kemajuan: otonomi daerah dan Otonomi

Award di Jawa Timur [Observing the regions propagating progress: regional autonomy

and the East Java Autonomy Awards], Jawa Pos Institute of Pro Otonomi, Surabaya,

January.

Simamora, Adianto P. (2008) VP denies talk of split between Mulyani, SBY, Jakarta Post,

11 August 2008.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2008) Evaluation of Mud Flood Disaster Alternatives in Sidoarjo Regency, Draft final report, UNEP, Jakarta, June.

World Bank and Asia Foundation (2005) Improving the Business Environment in East Java:

Views from the Private Sector, The World Bank and The Asia Foundation, Jakarta.

Yahya, K. (2007) Tantangan Penyelesaian dan Penanggulangan Lumpur Porong [The Challenge of Solving and Overcoming the Porong Mud Problem], Powerpoint presentation

for briefing to Sidoarjo Mudflow Handling Agency, Jakarta, February.

Вам также может понравиться

- Singapore Coastal Reclamation History and ProblemsДокумент7 страницSingapore Coastal Reclamation History and ProblemsDefzaОценок пока нет

- Environmental Sustainability of Open-Pit Coal Mining Practices at Baganuur, MongoliaДокумент20 страницEnvironmental Sustainability of Open-Pit Coal Mining Practices at Baganuur, MongoliaThomas MОценок пока нет

- Hanif Firmansyah - 113200102 - Iling B - Tugas Review PaperДокумент12 страницHanif Firmansyah - 113200102 - Iling B - Tugas Review Paper102Hanif FirmansyahОценок пока нет

- Likuifaksi Padang 42-345-1-PBДокумент15 страницLikuifaksi Padang 42-345-1-PBAbdi Septia PutraОценок пока нет

- Development ProjectДокумент3 страницыDevelopment Project23004245Оценок пока нет

- Journal Pre-Proof: Science of The Total EnvironmentДокумент42 страницыJournal Pre-Proof: Science of The Total Environmentmaristela vargasОценок пока нет

- Shrimp Farmers Innovation in Coping With The DisasterДокумент9 страницShrimp Farmers Innovation in Coping With The DisasterAchmad Room FitriantoОценок пока нет

- Sand Mining in India and Its Ramifications: (Type The Document Subtitle)Документ12 страницSand Mining in India and Its Ramifications: (Type The Document Subtitle)lovelycontractsОценок пока нет

- Peoples Reply Port City Sand MiningДокумент12 страницPeoples Reply Port City Sand MiningFeisal MansoorОценок пока нет

- Porong and Hot Mud DisasterДокумент30 страницPorong and Hot Mud DisasterAchmad Room FitriantoОценок пока нет

- Pollutionofthe Black SeabyoilproductsДокумент15 страницPollutionofthe Black SeabyoilproductsDaniela DanielaОценок пока нет

- Marine Pollution at Northeast of Penang IslandДокумент7 страницMarine Pollution at Northeast of Penang IslandAmir HafiyОценок пока нет

- Impacts of Mining On Water Resources in SouthДокумент8 страницImpacts of Mining On Water Resources in SouthFrancis Xavier GitauОценок пока нет

- 1-Dimensional Numerical Simulation For Sabo Dam Planning Using Kanako MethodДокумент11 страниц1-Dimensional Numerical Simulation For Sabo Dam Planning Using Kanako MethodmaccaferriasiaОценок пока нет

- IH Revision FinalДокумент7 страницIH Revision Finaluser0709Оценок пока нет

- Analysis of Eia For Obajana Gas Pipeline Project in NigeriaДокумент13 страницAnalysis of Eia For Obajana Gas Pipeline Project in NigeriaAnyanwu EugeneОценок пока нет

- Automated Trash Collector DesignДокумент11 страницAutomated Trash Collector DesignMuhammad RafiОценок пока нет

- ICTMASДокумент11 страницICTMASmuhammadОценок пока нет

- How The Global Appetite For Sand Is Fuelling A CrisisДокумент4 страницыHow The Global Appetite For Sand Is Fuelling A CrisisTushar AgrawalОценок пока нет

- Robert Moran's Report About Minas Conga 2012 - GRUFIDES PeruДокумент28 страницRobert Moran's Report About Minas Conga 2012 - GRUFIDES PeruMi Mina CorruptaОценок пока нет

- Surface Water Resources of Afghanistans NorthernДокумент10 страницSurface Water Resources of Afghanistans NorthernShaieq FrotanОценок пока нет

- Colombo Port City Causing Unimaginable Environmental HarmДокумент6 страницColombo Port City Causing Unimaginable Environmental HarmThavam RatnaОценок пока нет

- DAM Case 1Документ6 страницDAM Case 1Manmohan SinghОценок пока нет

- RRL Aga KhanДокумент5 страницRRL Aga KhanMuhaymin PirinoОценок пока нет

- Alluvial Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in A River Stream-Rutsiro Case Study (Rwanda)Документ24 страницыAlluvial Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in A River Stream-Rutsiro Case Study (Rwanda)PhilОценок пока нет

- Hawati 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 55 012048Документ9 страницHawati 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 55 012048azzahraОценок пока нет

- MandovibridgeIII FinalДокумент11 страницMandovibridgeIII FinalROHIT SHRIVASTAVAОценок пока нет

- PAD390Документ4 страницыPAD390MUHAMMAD NABIL MOHD ADAM MALEKОценок пока нет

- Benefits of Typhoons GQTabiosДокумент16 страницBenefits of Typhoons GQTabiosbautista.margaret9076Оценок пока нет

- Parakarama Samudraya - by Bandula KendaragamaДокумент5 страницParakarama Samudraya - by Bandula KendaragamaDilshan WimalarathnaОценок пока нет

- GJESM Volume 7 Issue 3 Pages 383-400Документ18 страницGJESM Volume 7 Issue 3 Pages 383-400GJESMОценок пока нет

- Sustainability 13 05301 With CoverДокумент18 страницSustainability 13 05301 With CoverNamish ShuklaОценок пока нет

- Determination of Heavy Metals in Sediments and Water From Johor RiverДокумент31 страницаDetermination of Heavy Metals in Sediments and Water From Johor RiverflojerzОценок пока нет

- Environmental Problemsof Surfaceand Underground MiningareviewДокумент10 страницEnvironmental Problemsof Surfaceand Underground MiningareviewsisiОценок пока нет

- Matai Assignment - S11196670Документ7 страницMatai Assignment - S11196670Joshika LataОценок пока нет

- Effects of Columbitetantalite (COLTAN)Документ9 страницEffects of Columbitetantalite (COLTAN)Jessica Patricia SitoeОценок пока нет

- Bibliography: Inquirand Application. International Edition. Boston: Mcgraw HillДокумент4 страницыBibliography: Inquirand Application. International Edition. Boston: Mcgraw HillAlfian RamadhanaОценок пока нет

- Dampak PertambanganДокумент8 страницDampak Pertambangandear_upeОценок пока нет

- Nuclear Power in SingaporeДокумент6 страницNuclear Power in SingaporeDenise Isebella LeeОценок пока нет

- Andiny - 2021 - IOP - Conf. - Ser. - Earth - Environ. - Sci. - 861 - 052030Документ10 страницAndiny - 2021 - IOP - Conf. - Ser. - Earth - Environ. - Sci. - 861 - 052030riowicaksonoОценок пока нет

- Prawira 2020 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 479 012044Документ11 страницPrawira 2020 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 479 012044Edilson LourencoОценок пока нет

- ENG 10 ArgДокумент4 страницыENG 10 ArgShyrill Mae MarianoОценок пока нет

- How The Global Appetite For Sand Is Fuelling A CrisisДокумент4 страницыHow The Global Appetite For Sand Is Fuelling A CrisisTushar AgrawalОценок пока нет

- E3sconf Agritechviii2023 04007Документ7 страницE3sconf Agritechviii2023 04007SyedaDF IkramОценок пока нет

- The Covid-19 Has A Positive Impact On Environment"-Do You Agree With This Statement? Why or Why NotДокумент2 страницыThe Covid-19 Has A Positive Impact On Environment"-Do You Agree With This Statement? Why or Why NotPi YaОценок пока нет

- 2016 Jaramillo Et Al JLandDeg AssessingRoleLimestoneQuarrySedimentSourceDevelopingTropicalCatchment OAДокумент35 страниц2016 Jaramillo Et Al JLandDeg AssessingRoleLimestoneQuarrySedimentSourceDevelopingTropicalCatchment OAsajiОценок пока нет

- Cebu Institue of Technology UniversityДокумент7 страницCebu Institue of Technology UniversitylukeОценок пока нет

- Final EIA Project Report For Exploratory Drilling in Block 10baДокумент607 страницFinal EIA Project Report For Exploratory Drilling in Block 10baEzzadin Baban0% (1)

- Sensors 18 04373Документ13 страницSensors 18 04373etsimoОценок пока нет

- Assessment of Temporal Estuarine Dynamics of Cimandiri River, Pelabuhanratu Bay, West Java, IndonesiaДокумент1 страницаAssessment of Temporal Estuarine Dynamics of Cimandiri River, Pelabuhanratu Bay, West Java, IndonesiaPudjiLestariОценок пока нет

- CorespondenceДокумент2 страницыCorespondenceulilamridaulayОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Climatic Changes On The Coastal Sandy Strip Extending From Gamasa in The West To Ras El Bar in The East, Northeastern Nile Delta, EgyptДокумент26 страницThe Effect of Climatic Changes On The Coastal Sandy Strip Extending From Gamasa in The West To Ras El Bar in The East, Northeastern Nile Delta, EgyptResearch ParkОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Coal Exploitation On Tidal Flat Changes, An Investigation Using Remote Sensing Data in VietnamДокумент12 страницThe Impact of Coal Exploitation On Tidal Flat Changes, An Investigation Using Remote Sensing Data in Vietnamvenus luciferОценок пока нет

- Climate Change and National Response BangladeshДокумент20 страницClimate Change and National Response BangladeshLaura DamayantiОценок пока нет

- 27875-Article Text-111907-9-10-20210203Документ14 страниц27875-Article Text-111907-9-10-20210203Musfira Dewi MОценок пока нет

- Science of The Total Environment: Ali P. Yunus, Yoshifumi Masago, Yasuaki HijiokaДокумент8 страницScience of The Total Environment: Ali P. Yunus, Yoshifumi Masago, Yasuaki HijiokaSantiago PuertaОценок пока нет

- HydrologyДокумент23 страницыHydrologyelizaОценок пока нет

- Ball Ent 2016Документ13 страницBall Ent 2016kateledianaОценок пока нет

- SBL - The Event - QuestionДокумент9 страницSBL - The Event - QuestionLucio Indiana WalazaОценок пока нет

- Brand Positioning of PepsiCoДокумент9 страницBrand Positioning of PepsiCoAbhishek DhawanОценок пока нет

- Reverse Engineering in Rapid PrototypeДокумент15 страницReverse Engineering in Rapid PrototypeChaubey Ajay67% (3)

- 5 Star Hotels in Portugal Leads 1Документ9 страниц5 Star Hotels in Portugal Leads 1Zahed IqbalОценок пока нет

- Avalon LF GB CTP MachineДокумент2 страницыAvalon LF GB CTP Machinekojo0% (1)

- Unit 1Документ3 страницыUnit 1beharenbОценок пока нет

- Epidemiologi DialipidemiaДокумент5 страницEpidemiologi DialipidemianurfitrizuhurhurОценок пока нет

- Tradingview ShortcutsДокумент2 страницыTradingview Shortcutsrprasannaa2002Оценок пока нет

- ARUP Project UpdateДокумент5 страницARUP Project UpdateMark Erwin SalduaОценок пока нет

- Lending OperationsДокумент54 страницыLending OperationsFaraz Ahmed FarooqiОценок пока нет

- Lea 4Документ36 страницLea 4Divina DugaoОценок пока нет

- Extent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home EconomicsДокумент47 страницExtent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home Economicschukwu solomon75% (4)

- Marine Lifting and Lashing HandbookДокумент96 страницMarine Lifting and Lashing HandbookAmrit Raja100% (1)

- 6 V 6 PlexiДокумент8 страниц6 V 6 PlexiFlyinGaitОценок пока нет

- Oem Functional Specifications For DVAS-2810 (810MB) 2.5-Inch Hard Disk Drive With SCSI Interface Rev. (1.0)Документ43 страницыOem Functional Specifications For DVAS-2810 (810MB) 2.5-Inch Hard Disk Drive With SCSI Interface Rev. (1.0)Farhad FarajyanОценок пока нет

- Environmental Auditing For Building Construction: Energy and Air Pollution Indices For Building MaterialsДокумент8 страницEnvironmental Auditing For Building Construction: Energy and Air Pollution Indices For Building MaterialsAhmad Zubair Hj YahayaОценок пока нет

- Online EarningsДокумент3 страницыOnline EarningsafzalalibahttiОценок пока нет

- Address MappingДокумент26 страницAddress MappingLokesh KumarОценок пока нет

- A Review Paper On Improvement of Impeller Design A Centrifugal Pump Using FEM and CFDДокумент3 страницыA Review Paper On Improvement of Impeller Design A Centrifugal Pump Using FEM and CFDIJIRSTОценок пока нет

- Properties of Moist AirДокумент11 страницProperties of Moist AirKarthik HarithОценок пока нет

- 3412C EMCP II For PEEC Engines Electrical System: Ac Panel DC PanelДокумент4 страницы3412C EMCP II For PEEC Engines Electrical System: Ac Panel DC PanelFrancisco Wilson Bezerra FranciscoОценок пока нет

- Employees' Pension Scheme, 1995: Form No. 10 C (E.P.S)Документ4 страницыEmployees' Pension Scheme, 1995: Form No. 10 C (E.P.S)nasir ahmedОценок пока нет

- 1 PBДокумент14 страниц1 PBSaepul HayatОценок пока нет

- Recall, Initiative and ReferendumДокумент37 страницRecall, Initiative and ReferendumPhaura Reinz100% (1)

- Lactobacillus Acidophilus - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент5 страницLactobacillus Acidophilus - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediahlkjhlkjhlhkj100% (1)

- Food and Beverage Department Job DescriptionДокумент21 страницаFood and Beverage Department Job DescriptionShergie Rivera71% (7)

- 1400 Service Manual2Документ40 страниц1400 Service Manual2Gabriel Catanescu100% (1)

- Action Plan Lis 2021-2022Документ3 страницыAction Plan Lis 2021-2022Vervie BingalogОценок пока нет

- Aircraftdesigngroup PDFДокумент1 страницаAircraftdesigngroup PDFsugiОценок пока нет

- Audit On ERP Implementation UN PWCДокумент28 страницAudit On ERP Implementation UN PWCSamina InkandellaОценок пока нет

- I Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)От EverandI Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (14)

- The Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeОт EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (90)

- Summary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (4)

- Financial Intelligence: How to To Be Smart with Your Money and Your LifeОт EverandFinancial Intelligence: How to To Be Smart with Your Money and Your LifeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (540)

- The Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeОт EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (2)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedОт EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (81)

- Financial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassОт EverandFinancial Literacy for All: Disrupting Struggle, Advancing Financial Freedom, and Building a New American Middle ClassОценок пока нет

- Summary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (15)

- A Happy Pocket Full of Money: Your Quantum Leap Into The Understanding, Having And Enjoying Of Immense Abundance And HappinessОт EverandA Happy Pocket Full of Money: Your Quantum Leap Into The Understanding, Having And Enjoying Of Immense Abundance And HappinessРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (159)

- Rich Dad Poor Dad: What the Rich Teach Their Kids About Money That the Poor and Middle Class Do NotОт EverandRich Dad Poor Dad: What the Rich Teach Their Kids About Money That the Poor and Middle Class Do NotОценок пока нет

- Summary of 10x Is Easier than 2x: How World-Class Entrepreneurs Achieve More by Doing Less by Dan Sullivan & Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary of 10x Is Easier than 2x: How World-Class Entrepreneurs Achieve More by Doing Less by Dan Sullivan & Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (24)

- Broken Money: Why Our Financial System Is Failing Us and How We Can Make It BetterОт EverandBroken Money: Why Our Financial System Is Failing Us and How We Can Make It BetterРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (3)

- The 4 Laws of Financial Prosperity: Get Conrtol of Your Money Now!От EverandThe 4 Laws of Financial Prosperity: Get Conrtol of Your Money Now!Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (389)

- Rich Bitch: A Simple 12-Step Plan for Getting Your Financial Life Together . . . FinallyОт EverandRich Bitch: A Simple 12-Step Plan for Getting Your Financial Life Together . . . FinallyРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (8)

- Quotex Success Blueprint: The Ultimate Guide to Forex and QuotexОт EverandQuotex Success Blueprint: The Ultimate Guide to Forex and QuotexОценок пока нет

- Love Money, Money Loves You: A Conversation With The Energy Of MoneyОт EverandLove Money, Money Loves You: A Conversation With The Energy Of MoneyРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (40)

- Summary of I Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. Just a 6-Week Program That Works by Ramit SethiОт EverandSummary of I Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. Just a 6-Week Program That Works by Ramit SethiРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (23)

- Rich Dad's Cashflow Quadrant: Guide to Financial FreedomОт EverandRich Dad's Cashflow Quadrant: Guide to Financial FreedomРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (1387)

- Bitter Brew: The Rise and Fall of Anheuser-Busch and America's Kings of BeerОт EverandBitter Brew: The Rise and Fall of Anheuser-Busch and America's Kings of BeerРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (52)

- A History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationОт EverandA History of the United States in Five Crashes: Stock Market Meltdowns That Defined a NationРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (11)

- Meet the Frugalwoods: Achieving Financial Independence Through Simple LivingОт EverandMeet the Frugalwoods: Achieving Financial Independence Through Simple LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (67)

- Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do MattersОт EverandFluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do MattersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (20)

- Sleep And Grow Rich: Guided Sleep Meditation with Affirmations For Wealth & AbundanceОт EverandSleep And Grow Rich: Guided Sleep Meditation with Affirmations For Wealth & AbundanceРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (105)

- The Holy Grail of Investing: The World's Greatest Investors Reveal Their Ultimate Strategies for Financial FreedomОт EverandThe Holy Grail of Investing: The World's Greatest Investors Reveal Their Ultimate Strategies for Financial FreedomРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (8)

- Passive Income Ideas for Beginners: 13 Passive Income Strategies Analyzed, Including Amazon FBA, Dropshipping, Affiliate Marketing, Rental Property Investing and MoreОт EverandPassive Income Ideas for Beginners: 13 Passive Income Strategies Analyzed, Including Amazon FBA, Dropshipping, Affiliate Marketing, Rental Property Investing and MoreРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (165)

- Unshakeable: Your Financial Freedom PlaybookОт EverandUnshakeable: Your Financial Freedom PlaybookРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (618)