Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Aviation in Transition: Challenges & Opportunities of Liberalization

Загружено:

Phan Thành Trung0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

23 просмотров8 страницBarry Humphreys, Chairman of IATA's International Aviation Issues Task Force, gave a presentation arguing for liberalized rules on airline ownership and control. He noted that while economic deregulation has benefited the airline industry and consumers, ownership and control rules have remained restrictive. Humphreys advocated treating airlines like other mature industries by removing barriers to foreign investment and cross-border mergers. He expressed optimism that the upcoming ICAO conference and EU-US negotiations would make progress on reforming outdated rules still based on protecting national carriers rather than a more global aviation market.

Исходное описание:

paper

Оригинальное название

Humphreys

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документBarry Humphreys, Chairman of IATA's International Aviation Issues Task Force, gave a presentation arguing for liberalized rules on airline ownership and control. He noted that while economic deregulation has benefited the airline industry and consumers, ownership and control rules have remained restrictive. Humphreys advocated treating airlines like other mature industries by removing barriers to foreign investment and cross-border mergers. He expressed optimism that the upcoming ICAO conference and EU-US negotiations would make progress on reforming outdated rules still based on protecting national carriers rather than a more global aviation market.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

23 просмотров8 страницAviation in Transition: Challenges & Opportunities of Liberalization

Загружено:

Phan Thành TrungBarry Humphreys, Chairman of IATA's International Aviation Issues Task Force, gave a presentation arguing for liberalized rules on airline ownership and control. He noted that while economic deregulation has benefited the airline industry and consumers, ownership and control rules have remained restrictive. Humphreys advocated treating airlines like other mature industries by removing barriers to foreign investment and cross-border mergers. He expressed optimism that the upcoming ICAO conference and EU-US negotiations would make progress on reforming outdated rules still based on protecting national carriers rather than a more global aviation market.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

Seminar prior to the ICAO Worldwide Air Transport Conference

Aviation in Transition:

Challenges & Opportunities of Liberalization

Session 3: Liberalized Airline Ownership and Control

Presentation by:

Barry Humphreys

Virgin Atlantic Airways

Chairman - IATA International Aviation Issues Task Force

ICAO Headquarters

Montreal

22 and 23 March 2003

ICAO SEMINAR, 22/23 MARCH 2003

Aviation in Transition : Challenges & Opportunities of

Liberalisation

Liberalised Airline Ownership and Control

Barry Humphreys, Director of External Affairs & Route

Development, Virgin Atlantic Airways, and Chairman, IATA

International Aviation Issues Task Force.

Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen.

It is a pleasure

to be in Montreal again, despite the cold, and an honour

to be invited to address you on the subject of airline

ownership and control rules.

As I am sure you all know, later this year we are

celebrating the 100th anniversary of the first powered

flight by the Wright brothers.

What many of you may not

be so well aware of is that this year is also the 150th

anniversary of another milestone in the development of

aviation.

Sir George Cayley was born in Yorkshire,

England, in 1773 and lived for almost 84 years.

prodigious inventor.

He was a

For example, in 1825 he invented

the caterpillar tractor, from which derive all modern

tracked vehicles of peace and war.

But it was in the sphere of aeronautics that Cayley

really stood out.

He was recognised by many, including

the Wright brothers, as the father of aeronautics, or as

the Frenchman Charles Dollfus and Henry Bouch said, the

real inventor of the aeroplane.

Alphonse Berget, also

of France, in 1909 described Cayley as the incontestable

forerunner of aviation.

In 1853, 150 years ago, Cayley built and flew what he

called his new flyer, the worlds first man-carrying

(but not piloted) glider flight.

Being 80 years old by

this time, and no fool, Sir George did not actually fly

in this aircraft himself.

Instead, he instructed his

coachman, his far from enthusiastic coachman, to get

aboard, eliciting the immortal words: You must be

joking!.

Actually, the words were: Please, Sir George,

I wish to give notice.

fly.

I was hired to drive, and not to

However, industrial relations being what they were

in 1853, fly the coachman most certainly did, across a

dale in Sir Georges home estate.

And probably as much

to his surprise as anyones, he survived.

Anyway, whether we are celebrating a 100th or 150th

anniversary, one point is clear: aviation is not an

immature young industry.

Air transport has made enormous

progress over the decades and no longer needs to be

treated as a special industry requiring protection.

The archaic rules and regulations that have become

associated with this business have long since outlived

their usefulness, if they ever had a use.

Few would now argue that economic liberalisation brings

substantial benefits to both the industry and the

travelling public.

Over the past 20 years or so we have

seen the deregulation of domestic air services within the

United States, the creation of the internal market in the

European Union, the signing of no less than 53 open skies

bilateral agreements by the US, as well as numerous other

examples of airlines being freed from the shackles of

regulation.

There are still some who resist this reform,

or who doubt its positive results, but it is clear that

the momentum for economic liberalisation in air transport

is now unstoppable.

However, there is one major area of activity that so far

has remained almost untouched by reform.

That is the

rules governing who may and may not own and control an

airline.

It is true that within the EU these rules have

been relaxed, and we have seen a brave experiment by

Australia to allow 100% foreign ownership of domestic

carriers.

A few other countries have similarly dabbled

with reform.

But fundamentally air transport still

stands out as a major industry forced to operate

according to highly restrictive ownership rules.

These rules fall into two separate categories:

-

restrictions on who may own and control a national

airline;

the right of a country to refuse to accept the

designation of an airline under a bilateral air

services agreement if that airline is not majority

owned and controlled by citizens of the country of

designation.

To say that the retention of these restrictions borders

on madness is an understatement.

What is so special

about air transport that it requires to be treated so

differently from most other businesses?

I have spoken

many times of the fact that overwhelmingly most of the

250 or so companies that make up the Virgin Group are

free to expand or invest in other countries.

Indeed, as

with most foreign investment, countries and regions go to

enormous trouble and expense to encourage such

investment.

Thus, in North America alone Virgin has

invested in retail outlets, mobile telephones, ground

transportation, soft drinks, and so on.

Yet when we

declare that we would also like to set up an airline

here, hands are thrown up in horror.

There is a major irony in all this.

By its nature

international air transport is a global business, yet

there is not a single global airline.

We have seen

repeatedly how attempts at cross-border airline mergers

or take-overs have been frustrated because of the fear of

the loss of the all-important bilateral traffic rights.

Instead of consolidation that other industries are free

to engage in, airlines have been forced to form loose,

unstable alliances that many believe do not offer a longterm solution to many of the industrys problems.

For me, the answer is very simple.

Air transport should

be treated just like any other mature industry.

The

question is not whether rules governing ownership and

control, or cabotage, or aircraft leasing, or anything

else, should be reformed, but rather why on earth would

anyone want to keep such restrictions?

For an industry

with the financial problems that face aviation at

present, it is extremely short-sighted to build in

barriers to the full access to the global capital market.

We are just shooting ourselves in the foot, indeed in

both feet.

Fortunately there is real hope of reform, especially for

opening up airline ownership structures to foreign

participation.

I have lost count of the number of

conferences and seminars I have attended over the past

couple of years at which this has been one of the

principal topics for discussion.

Overwhelmingly the

consensus has been in favour of reform, and even of

radical reform.

Governments cannot ignore such pressure,

and I very much hope that we shall see widespread support

for a more logical approach to this critically important

subject at the ICAO Worldwide Air Transport Conference

next week.

IATA has devoted considerable resources to developing a

policy on airline ownership and control, and I was

fortunate to be invited to chair the group of airlines

from around the world charged with undertaking this task.

IATA, of course, represents airlines from every

background and geographical region.

The fact that IATA

was able to produce a policy that was acceptable to the

membership at large should surely indicate that there is

every reason to expect that governments themselves will

similarly be able to agree on reform.

The key to IATAs approach is that irrespective of a

countrys policy towards the ownership of its own

airlines, it should not stand in the way of other

countries adopting a more liberal policy.

In other

words, if Japan, for example, decides to continue to

insist that Japanese airlines are majority owned and

controlled by Japanese citizens, it should not object to,

say, French or Australian carriers being owned and

controlled by non-Frenchmen or non-Australians.

That is

a very modest reform in many ways, but potentially it

could make an enormous difference to the future structure

of the aviation industry by removing the main barrier to

cross-border mergers and take-overs.

With the recent decision of the European Court of

Justice, of course, there will inevitably be considerable

pressure on countries to accept the designation of EU

airlines rather than national airlines of individual EU

States.

There is also the hope, even expectation, that

negotiations between the EU and US, when they eventually

take place, will result in the creation of a TransAtlantic Common Aviation Area, and subsequently even a

broader Common Aviation Area, with no restrictions at all

on ownership and control.

Understandably there is concern that economic

liberalisation should not bring with it any diminution in

safety standards.

No-one wants to see the creation of

flags of convenience in aviation.

IATAs solution is

to propose that any airline designated by a country

should have an Air Operators Certificate from that

country.

That would certainly go a long way towards

removing the concern about safety.

However, it may not

satisfy the European Commission, which insists that an

AOC from any EU State should be sufficient for

designation by any other EU Member.

Handling this issue

will be one of the more interesting and potentially

difficult areas in the forthcoming EU/US negotiations.

So, in conclusion, the archaic ownership and control

rules which continue to apply in the air transport

industry are well past their sell-by date.

Their removal

will do more than anything else to drag the industry into

the 20th if not the 21st Century.

Despite continued

resistance to reform from certain quarters, I am

optimistic that the next few years will see considerable

progress.

I certainly look forward to the day when the

Virgin Group will be able to follow its success in

establishing airlines in the UK, Brussels and Australia

with other carriers in other parts of the world.

Thank you.

Barry Humphreys

Director of External Affairs & Route Development

Virgin Atlantic Airways

22 March 2003

Nb.

References to Sir George Cayley are taken from Sir

George Cayleys Aeronautics 1796-1855 by Charles H.

Gibbs-Smith (HMSO, 1962).

Вам также может понравиться

- London's Airports: Useful Information on Heathrow, Gatwick, Luton, Stansted and CityОт EverandLondon's Airports: Useful Information on Heathrow, Gatwick, Luton, Stansted and CityОценок пока нет

- AE Week 5 Colony Chapther 1-3Документ55 страницAE Week 5 Colony Chapther 1-3Ömer YağmurОценок пока нет

- What Went Wrong: Twenty Years of Airline Accidents (1996 to 2015)От EverandWhat Went Wrong: Twenty Years of Airline Accidents (1996 to 2015)Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Open Skies Policy Advantages and DisadvantagesДокумент7 страницOpen Skies Policy Advantages and DisadvantagesJOHN PAUL AQUINOОценок пока нет

- Crowded Skies Can Be A Big Risk Need New Air Corridors .Define?Документ9 страницCrowded Skies Can Be A Big Risk Need New Air Corridors .Define?Deepak Warrier KОценок пока нет

- Speech by Willie WalshДокумент28 страницSpeech by Willie Walshrgovindan123Оценок пока нет

- TechLog JanFeb08Документ28 страницTechLog JanFeb08Vi DangОценок пока нет

- COVID-19's Impact on Australian Business ManagementДокумент9 страницCOVID-19's Impact on Australian Business ManagementVibhav.b. rajОценок пока нет

- ICC Calls for Greater Liberalization of International Air TransportДокумент8 страницICC Calls for Greater Liberalization of International Air TransportMohd Saiful IzwanОценок пока нет

- The Role and Responsibility of Flag States Under Unclos IIIДокумент7 страницThe Role and Responsibility of Flag States Under Unclos IIIapi-341520052Оценок пока нет

- Why Air Travel Is The Safest Mode of TransportДокумент2 страницыWhy Air Travel Is The Safest Mode of TransportEdan HerlihyОценок пока нет

- 2 Introduction To Airline OperationsДокумент21 страница2 Introduction To Airline OperationsRaniaОценок пока нет

- Recommended Practices For Charter Operations: The British Helicopter AssociationДокумент5 страницRecommended Practices For Charter Operations: The British Helicopter AssociationNICOLEFOCONEОценок пока нет

- ICAO Working Paper Calls for Replacing Bilateral Air Services Agreements with Modern Multilateral FrameworkДокумент4 страницыICAO Working Paper Calls for Replacing Bilateral Air Services Agreements with Modern Multilateral FrameworkJamesОценок пока нет

- First European Rotorcraft and Powered Lift Aircraft Forum Paper on Intercity VTOL AircraftДокумент30 страницFirst European Rotorcraft and Powered Lift Aircraft Forum Paper on Intercity VTOL Aircraftbutterstick9131Оценок пока нет

- The Airline Industry01Документ11 страницThe Airline Industry01Yasitha LakpathiОценок пока нет

- Capital and Market Access in International Aviation: Nationality Requirements and Cabotage RestrictionsДокумент22 страницыCapital and Market Access in International Aviation: Nationality Requirements and Cabotage RestrictionsNidhi PrakritiОценок пока нет

- Stelios Haji-Ionnou and EasyjetДокумент5 страницStelios Haji-Ionnou and EasyjetNurul NajihahОценок пока нет

- 2006 InterVISTASДокумент139 страниц2006 InterVISTASKatiaОценок пока нет

- ICAO Aviation Training and Capacity-Building Roadmap - 2017Документ4 страницыICAO Aviation Training and Capacity-Building Roadmap - 2017Toto SubagyoОценок пока нет

- Impact of Airline Deregulation Act 1978 on Aviation IndustryДокумент13 страницImpact of Airline Deregulation Act 1978 on Aviation IndustrySufyan MalikОценок пока нет

- Hafizul Ikmal Mamun Online TestДокумент4 страницыHafizul Ikmal Mamun Online TestHafizul Ikmal MamunОценок пока нет

- Indian Airline Industry AnalysisДокумент15 страницIndian Airline Industry Analysisekta_1011Оценок пока нет

- Globalization in Aviation Sector: India's ExperienceДокумент22 страницыGlobalization in Aviation Sector: India's ExperiencePrashant Maurya100% (1)

- Discuss 3 Shipping Organizations Other Than IMOДокумент5 страницDiscuss 3 Shipping Organizations Other Than IMORahimee DahlanОценок пока нет

- BRM Project Airlines ReportДокумент10 страницBRM Project Airlines ReportG.Meghana100% (1)

- Journal of Air Law and Commerce. Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit Into The World Trade OrganizationДокумент67 страницJournal of Air Law and Commerce. Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit Into The World Trade OrganizationAva ChuaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Air Freight - Historical Perspective Industry Background and Key TrendsДокумент11 страницChapter 1 Air Freight - Historical Perspective Industry Background and Key TrendsjozsakevinОценок пока нет

- CAP 658 Model Aircraft: A Guide To Safe Flying: Safety Regulation GroupДокумент54 страницыCAP 658 Model Aircraft: A Guide To Safe Flying: Safety Regulation GroupGSAT200Оценок пока нет

- Confessions of an Air Craft Pilot: Including Tales from the Pilot’s SeatОт EverandConfessions of an Air Craft Pilot: Including Tales from the Pilot’s SeatРейтинг: 1 из 5 звезд1/5 (1)

- Aviation Law Term Paper TopicsДокумент7 страницAviation Law Term Paper Topicsc5haeg0n100% (1)

- Icao and Air LawДокумент8 страницIcao and Air LawRamaRajuKОценок пока нет

- Aviation Whitepaper OverviewДокумент10 страницAviation Whitepaper OverviewpeladosОценок пока нет

- Quality Cost ImprovementДокумент14 страницQuality Cost ImprovementalexxastanОценок пока нет

- 2 History of AviationДокумент31 страница2 History of Aviationmadiha fatimaОценок пока нет

- IATA Passenger RightsДокумент3 страницыIATA Passenger Rightshosseinr13Оценок пока нет

- Emirates Customer ServiceДокумент20 страницEmirates Customer ServiceAjay Padinjaredathu AppukuttanОценок пока нет

- Strategic Alliances in The Global Airline IndustryДокумент45 страницStrategic Alliances in The Global Airline IndustryOluseyi Adeyemo100% (2)

- Safety Was No Accident: History of the Uk Civil Aviation Flying Unit Cafu 1944 -1996От EverandSafety Was No Accident: History of the Uk Civil Aviation Flying Unit Cafu 1944 -1996Оценок пока нет

- Globalization, Liberalization and Privatization of Aviation IndustryДокумент20 страницGlobalization, Liberalization and Privatization of Aviation Industryshekar20Оценок пока нет

- Col RegsДокумент5 страницCol RegsDharmendra ShawОценок пока нет

- Convention on International Civil Aviation: A CommentaryОт EverandConvention on International Civil Aviation: A CommentaryОценок пока нет

- Regulatory Changes in International Air Transport and Their Impact On Tourism Development in Asia PacificДокумент22 страницыRegulatory Changes in International Air Transport and Their Impact On Tourism Development in Asia PacificRichard Agung HidayatОценок пока нет

- Global Airline Management Ch-2 Intl Institutional Reg Env-Arif V3Документ32 страницыGlobal Airline Management Ch-2 Intl Institutional Reg Env-Arif V3MUHAMMAD UMER FAROOQОценок пока нет

- Plane Truth: Aviation's Real Impact on People and the EnvironmentОт EverandPlane Truth: Aviation's Real Impact on People and the EnvironmentОценок пока нет

- 1981 GlasserДокумент168 страниц1981 GlasserMs. Madhumitha AnvekarОценок пока нет

- HeathrowДокумент5 страницHeathrowBrian RayОценок пока нет

- Aviavtion InsuranceДокумент53 страницыAviavtion InsuranceMinal DalviОценок пока нет

- Articles International Shipping ManagementДокумент4 страницыArticles International Shipping Managementjosephinebenoit1Оценок пока нет

- Structure & Development of The Air Transport Industry TAL035-1Документ5 страницStructure & Development of The Air Transport Industry TAL035-1Rohit RajputОценок пока нет

- ICAO Working Paper Examines Slot Allocation IssuesДокумент8 страницICAO Working Paper Examines Slot Allocation IssuesJamesОценок пока нет

- Flight Disruptions in Addis Ababa - EditedДокумент25 страницFlight Disruptions in Addis Ababa - EditedRaini RodneyОценок пока нет

- Preventing A Cyber-9 - 11 - How Universal Jurisdiction Could ProtectДокумент50 страницPreventing A Cyber-9 - 11 - How Universal Jurisdiction Could ProtectUddeshyaPandeyОценок пока нет

- B J Atc U F:: Usiness Ets and Ser EesДокумент40 страницB J Atc U F:: Usiness Ets and Ser EesreasonorgОценок пока нет

- Air Transport LawДокумент7 страницAir Transport LawAnonymous G5ScwBОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Ethical Leadership and OrganizationaДокумент7 страницThe Effect of Ethical Leadership and OrganizationaPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Fundamentals of Academic Writing Level 1 PDFДокумент236 страницFundamentals of Academic Writing Level 1 PDFQUỲNH ĐẶNG79% (19)

- Private International Air Law: Faculty of Law - Mcgill UniversityДокумент5 страницPrivate International Air Law: Faculty of Law - Mcgill UniversityPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Journal of Transport Geography Volume 22 Issue None 2012 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jtrangeo.2011.12.002) Jingyi Lin - Network Analysis of Chinaâ ™s Aviation System, Statistical and Spatial StructureДокумент12 страницJournal of Transport Geography Volume 22 Issue None 2012 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jtrangeo.2011.12.002) Jingyi Lin - Network Analysis of Chinaâ ™s Aviation System, Statistical and Spatial StructurePhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- 2203286-You Are My EverythingДокумент5 страниц2203286-You Are My EverythingPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Reynolds-Feighan and Vega: Structural Centrality Relations in The Global Air Transport SystemДокумент9 страницReynolds-Feighan and Vega: Structural Centrality Relations in The Global Air Transport SystemPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- W - Sway PDFДокумент2 страницыW - Sway PDFPhan Thành Trung100% (2)

- Case StudyДокумент455 страницCase StudyGalih Kusumah80% (10)

- 1 e Freight Fundamentals 130226120550 Phpapp01 PDFДокумент25 страниц1 e Freight Fundamentals 130226120550 Phpapp01 PDFprathamesh kaduОценок пока нет

- Acoustic - Dau Mua PDFДокумент4 страницыAcoustic - Dau Mua PDFPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- (29-12-2015 15.06.00) Lich Thi hk1 2015 2016Документ146 страниц(29-12-2015 15.06.00) Lich Thi hk1 2015 2016Phan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- The Objectives of The Course Include As FollowsДокумент4 страницыThe Objectives of The Course Include As FollowsPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- 1302 7017 PDFДокумент28 страниц1302 7017 PDFPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Journal of Transport Geography: Jingyi LinДокумент9 страницJournal of Transport Geography: Jingyi LinPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Performance Indicators Identify Key Dimensions for Evaluating Bus Transit SystemsДокумент10 страницPerformance Indicators Identify Key Dimensions for Evaluating Bus Transit SystemsPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Journal of Air Transport Management Volume 28 Issue 2013 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jairtraman.2012.12.010) Daft, Jost Albers, Sascha - A Conceptual Framework For Measuring Airline Business Model ConvergeДокумент12 страницJournal of Air Transport Management Volume 28 Issue 2013 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jairtraman.2012.12.010) Daft, Jost Albers, Sascha - A Conceptual Framework For Measuring Airline Business Model ConvergePhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Management Emphasis and Performance in The Airline Industry: An Exploratory Multilevel AnalysisДокумент21 страницаManagement Emphasis and Performance in The Airline Industry: An Exploratory Multilevel AnalysisPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Analysis of The Airport Network of India As A Complex Weighted Network Ganesh BaglerДокумент9 страницAnalysis of The Airport Network of India As A Complex Weighted Network Ganesh BaglergansbagsОценок пока нет

- Transportation Research Part D: Milan JanicДокумент13 страницTransportation Research Part D: Milan JanicPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- System For Assessing Aviation's Global Emissions (SAGE), Part 1: Model Description and Inventory ResultsДокумент22 страницыSystem For Assessing Aviation's Global Emissions (SAGE), Part 1: Model Description and Inventory ResultsPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Transport Policy: Wei Min Liu, Maria K.R. LukДокумент9 страницTransport Policy: Wei Min Liu, Maria K.R. LukPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Modelling Operational, Economic and Environmental Performance of An Air Transport NetworkДокумент18 страницModelling Operational, Economic and Environmental Performance of An Air Transport NetworkPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Evolution of China's Air Transport NetworkДокумент14 страницEvolution of China's Air Transport NetworkPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Measuring Airportsõ Operating E Ciency: A Summary of The 2003 Atrs Global Airport Benchmarking ReportДокумент18 страницMeasuring Airportsõ Operating E Ciency: A Summary of The 2003 Atrs Global Airport Benchmarking ReportPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Aviation and Externalities: The Accomplishments and ProblemsДокумент22 страницыAviation and Externalities: The Accomplishments and ProblemsPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Journal of Transport Geography: Megan S. Ryerson, Xin GeДокумент12 страницJournal of Transport Geography: Megan S. Ryerson, Xin GePhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Measuring Performance in the Air Transportation IndustryДокумент4 страницыMeasuring Performance in the Air Transportation IndustryPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Sustainable Public Transport Systems: Moving Towards A Value For Money and Network-Based Approach and Away From Blind CommitmentДокумент5 страницSustainable Public Transport Systems: Moving Towards A Value For Money and Network-Based Approach and Away From Blind CommitmentPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Journal of Air Transport Management Volume 4 Issue 3 1998 (Doi 10.1016 - s0969-6997 (98) 00015-5) Anming Zhang - Industrial Reform and Air Transport Development in ChinaДокумент20 страницJournal of Air Transport Management Volume 4 Issue 3 1998 (Doi 10.1016 - s0969-6997 (98) 00015-5) Anming Zhang - Industrial Reform and Air Transport Development in ChinaPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Journal of Transport Geography: Jingyi LinДокумент9 страницJournal of Transport Geography: Jingyi LinPhan Thành TrungОценок пока нет

- Crisis Scapes: Athens and BeyondДокумент224 страницыCrisis Scapes: Athens and Beyondcrisis-scape.net100% (4)

- Environmental ChangesДокумент11 страницEnvironmental ChangesMichelle Alejo Cortez50% (2)

- 966h PDFДокумент13 страниц966h PDFaeylxd100% (3)

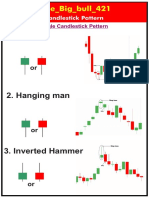

- ProfitX CandlesДокумент27 страницProfitX CandlesDickson MakoriОценок пока нет

- How globalization impacts international business studentsДокумент6 страницHow globalization impacts international business studentsVeron Low Ching ShuangОценок пока нет

- 08 Monica Condruz Bacescu English in Romania From The Past To The PresentДокумент8 страниц08 Monica Condruz Bacescu English in Romania From The Past To The PresentROXANA UNGUREANUОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Objectives and Organisation of The WTO: 1.1 What Is The World Trade Organization?Документ12 страницChapter 1 Objectives and Organisation of The WTO: 1.1 What Is The World Trade Organization?hailian560Оценок пока нет

- Burkner 2012 Intersectionality and Inequality-Rev PDFДокумент15 страницBurkner 2012 Intersectionality and Inequality-Rev PDFWildFlowerОценок пока нет

- Standing. Global Feminization Through Flexible LaborДокумент20 страницStanding. Global Feminization Through Flexible LaborGugu Mc Anthony NgcoboОценок пока нет

- Land Reform in Latin America - Political Science - Oxford BibliographiesДокумент21 страницаLand Reform in Latin America - Political Science - Oxford BibliographiesSebastian Diaz AngelОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 GlobalizationДокумент42 страницыChapter 1 GlobalizationPeko YeungОценок пока нет

- Share MarketДокумент10 страницShare MarketAk Reviews100% (1)

- A. Globalization and Challenges: What Are Globalization's Contemporary IssuesДокумент5 страницA. Globalization and Challenges: What Are Globalization's Contemporary IssuesCamille San GabrielОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1: International ManagementДокумент31 страницаChapter 1: International ManagementMey Sandrasigaran100% (2)

- Schedule Fall SemesterДокумент8 страницSchedule Fall SemesterEl AndrésОценок пока нет

- Republic of the Philippines Globalization DocumentДокумент10 страницRepublic of the Philippines Globalization DocumentBRILIAN GUMAYAGAY TOMAS91% (112)

- VELASCO, Sharmaine J. BAPS 2A GRADED RECITATION 3 CWДокумент3 страницыVELASCO, Sharmaine J. BAPS 2A GRADED RECITATION 3 CWSharmaine Javinar VelascoОценок пока нет

- Multicultural Incarnations: Race, Class and Urban Renewal: Maree PardyДокумент15 страницMulticultural Incarnations: Race, Class and Urban Renewal: Maree Pardyana_australianaОценок пока нет

- Filipino Culture and Global Media's Influence Around the WorldДокумент37 страницFilipino Culture and Global Media's Influence Around the WorldNinaGonzalesОценок пока нет

- Toyota Chairman's MessageДокумент2 страницыToyota Chairman's MessageVishal ChОценок пока нет

- Guide To SDGs in Rwanda ENGДокумент2 страницыGuide To SDGs in Rwanda ENGCliffDaddyySiboОценок пока нет

- Temas de Investigación: Enfoque SistemicoДокумент10 страницTemas de Investigación: Enfoque SistemicoIrvin Fernando Mendoza RosadoОценок пока нет

- العلاقة بين السياستين المالية والنقدية ودورها في تحقيق التوازن الاقتصاديДокумент12 страницالعلاقة بين السياستين المالية والنقدية ودورها في تحقيق التوازن الاقتصاديMohamedОценок пока нет

- GLOBALIZATION: A PROCESS OF UNIFICATIONДокумент4 страницыGLOBALIZATION: A PROCESS OF UNIFICATIONSmart RoastОценок пока нет

- History Sba Notes 1Документ5 страницHistory Sba Notes 1MarcusAbrahamОценок пока нет

- Abram de Swaan Words of The World 2001Документ11 страницAbram de Swaan Words of The World 2001Marco ZanettiОценок пока нет

- I Didn't Know What Time It Was - BBДокумент1 страницаI Didn't Know What Time It Was - BBDavid7635Оценок пока нет

- Gso.215.e.1994-Pressure Equipments PDFДокумент28 страницGso.215.e.1994-Pressure Equipments PDFodaueОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan Subject: Social Science-Political Science Class: X Month: November No of Periods: 9 Chapter: Manufacturing IndustriesДокумент10 страницLesson Plan Subject: Social Science-Political Science Class: X Month: November No of Periods: 9 Chapter: Manufacturing Industriesrushikesh patil100% (1)

- Variegated Capitalism: Jamie Peck and Nik TheodoreДокумент42 страницыVariegated Capitalism: Jamie Peck and Nik TheodoreChloe VellaОценок пока нет