Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

GJHS 6 221

Загружено:

Teuku FaisalОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

GJHS 6 221

Загружено:

Teuku FaisalАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Global Journal of Health Science; Vol. 6, No.

4; 2014

ISSN 1916-9736

E-ISSN 1916-9744

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education

Comparison of Complications in Percutaneous Dilatational

Tracheostomy versus Surgical Tracheostomy

Siamak Yaghoobi1, Hamid Kayalha1, Raziyeh Ghafouri2, Zohreh Yazdi2 & Marzieh Beigom Khezri1

1

Department of Anesthesiology, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

School of Medicine, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran

Correspondence: Marzieh Beigom Khezri, Associate Professor of Qazvin Medical University Science,

Department of Anesthesiology, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Bahonar, Ave 3419759811, PO Box 34197/59811,

Qazvin, Iran. Tel: 98-912-381-1009. Fax: 98-281-223-6378. E-mail: mkhezri@qums.ac.ir

Received: January 18, 2014

doi:10.5539/gjhs.v6n4p221

Accepted: March 5, 2014

Online Published: April 20, 2014

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v6n4p221

The authors of this paper have not declared any conflicts of interest

Abstract

Background: Tracheostomy facilitates respiratory care and the process of weaning from mechanical ventilatory

support.

Aims: To compare the complications found in percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) and surgical

tracheostomy (ST) techniques.

Methods: This was a prospective randomized study to evaluate the complications of PDT and ST procedures in

patients admitted to ICU unit of a teaching hospital during 2008 to 2011.

We studied 40 patients in each group. PDTs were performed with blue rhino technique at the bedside by a skilled

clinician and all cases of STs performed by Charles G Durbin technique in operating room under general

anesthesia. Bronchoscopic examination through tracheostomy tube was performed to ensure the correct position

of tracheostomy tube in the trachea lumen. The duration of procedures and pre- and post-interventional

complications were recorded.

Results: The most common complications observed in the PDT group were minor bleeding (n=4), hypoxemia,

and cardiac dysrhythmias (n=3) whereas in the ST group, the most frequent complications were minor bleeding

(n=5) and endotracheal tube puncture (n=3). The difference in overall complications between the two groups was

insignificant (P=0.12).

Conclusion: PDT with blue rhino technique is a safe, quick, and effective method while the overall

complications in both groups were comparable.

Keywords: tracheostomy, percutaneous, dilatational tracheostomy, blue rhino

1. Introduction

Tracheostomy is considered as the airway management of choice for patients who need prolonged mechanical

ventilation support or airway protection (Boonsarngsuk, Kiatboonsri, & Choothakan, 2007). It facilitates the

respiratory care and the process of weaning from mechanical ventilatory support (Rudr, 2002).

Tracheostomy has several advantages over translaryngeal intubation including better patient tolerance, reduced

laryngeal irritation, easier nursing care, enhanced ability to communicate, and reduced dead space and work of

breathing (Griffiths, Barber, Morgan, & Young, 2005). Approximately 5 to 13% of patients on mechanical

ventilation will be in need of prolonged mechanical ventilation (>21 days). In these patients, the critical care

personnel have to make a decision on whether and when to perform a tracheostomy (Bartolome, 2012). This

decision is individually based on the risk and benefits of tracheostomy and prolonged intubation and also the

patient's family preferences and expected clinical outcomes. Nowadays, most intensivists agree that if a patient is

in need of MV for more than 1014 days, a tracheostomy is indicated and should be planned under optimal

conditions (Bartolome, 2012). However, tracheostomy can be performed at intensive care units (ICU) as a bed

221

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs

Global Journal of Health Science

Vol. 6, No. 3; 2014

side procedure or in an operating room setting (Durbin, 2005). With advanced technology and increasing interest

in minimally invasive procedures, variations on standard open surgical tracheostomy have been evolved over the

recent years. Therefore, it seems that percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy has gained the popularity to become

a common method in critically ill patients. Dilatational tracheostomy might be performed through several

different approaches and systems. In ICUs, the most common indication for the application of PDT is a need for

prolonged mechanical ventilation in cases such as severe brain injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and

severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or multiple organ failure. However, indications, risks, benefits,

timing, and the technique of the procedure remain controversial and depend on the clinical condition of the

patient in particular the respiratory status. (Durbin, 2005; Groves et al., 2007). Furthermore, the ability of

clinicians to predict which patients required extended ventilatory support was limited (Young et al., 2013).

(Young, Harrison, Cuthbertson, Rowan; TracMan Collaborators, 2013).

It is reported that tracheostomies with blue rhino technique is a modified version of the Ciaglia technique

(Ciaglia, Firsching, Syniec,1985; Byhahn et al., 2000), in which the dilatation of the stoma is performed in a

single step by means of a hydrophylically coated, curved dilator- the blue rhino. Therefore, insertion of

tracheostomy tube was performed more rapid and the risk of posterior tracheal wall injury and intraoperative

bleeding was reduced while the adverse effect on oxygenation during repeated airway obstruction by the dilators

was avoided.

In Iran, PDT is performed only in limited number of centers and there is little data about the outcome. The aim

of the present study was to compare the surgical tracheostomy with PDT in intensive care patients, with special

consideration on technical difficulties including the duration of procedure, and the intra- and post-operative

complications.

2. Methods

2.1 Design and Participants

This was a randomized prospective analysis to compare the results of PDT with surgical tracheostomy performed

on patients admitted to ICU unit of a teaching hospital from March 2008 to September 2011. Inclusion criteria

were all critically ill patients in the general ICUs with age>18, the necessity of mechanical ventilation for 2

week, and hemodynamic stability. Exclusion criteria included infection of tracheostomy site, abnormal neck

anatomy, known or suspected difficult endotracheal intubation, unstable cervical spine, age <18 years,

uncorrectable coagulopathy, hemodynamic instability, and a history of previous tracheostomy. Informed written

consents were obtained from the relatives and the study was prospectively approved by the Hospitals Ethics

Committee for human studies. All patients were randomized into two groups using computer-generated random

numbers.

2.2 Tracheostomy Procedures

All PDTs were performed with blue rhino technique kit at the bedside in the ICU and all surgical tracheostomies

in the operating room, both under general intravenous anesthesia. The drugs used for the induction of anesthesia

consisted of fentanyl (50-100 g), midazolam (2 mg), propofol (1-2 mg/kg), and atracurium (0.5 mg/ kg),

prescribed intravenously. This protocol also included continuous intravenous propofol (50 mg/kg/min). All

patients were preoxygenated with 100% oxygen for 8-10 minutes and the vital signs, pulse oximetry, and

electrocardiograms were continuously monitored throughout. All PDTs were performed by the same intensivist

and all surgical tracheostomies by the same surgeon. The tracheostomy site was marked 3 cm above the sternal

notch. Lidocaine 1% with 1/200,000 diluted epinephrine was infiltrated subcutaneously to reduce bleeding. Later,

the fiberoptic bronchoscope was placed in the endotracheal tube and in case of the presence of endotracheal

secretions it was removed through suctioning. While the cuff of the tracheal tube was deflated and the rings of

trachea were visualized with bronchoscope to prevent puncture, the tube was withdrawn until the tip was just in

the larynx. Over the guidewire and guiding catheter, the blue rhino was passed to the appropriate skin level

marking, resulting in tracheal dilation. Finally, the tracheostomy tube was inserted through the tracheal stoma.

Later, the introducer, the guidewire, and the guiding catheter were removed, leaving the tracheostomy tube in

situ. The cuff of the tracheostomy tube was fully inflated, the ventilator breathing circuit connected, and the tube

was fixed with tapes around the neck. Satisfactory ventilation was verified bilaterally by auscultation of the chest.

Tracheal suctioning was performed to remove secretions and blood. Surgical tracheostomies were performed by

Charles G Durbin technique (Durbin, 2005).

2.3 Measures

The duration of procedures and pre- and post-interventional complications including hypotension, hypoxemia,

222

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs

Global Journal of Health Science

Vol. 6, No. 3; 2014

cardiac dysrhythmias, difficult tube placement, endotracheal tube cuff leak, minor and major bleeding,

tracheostomy-associated death, stomal infection, posterior tracheal wall injury, and tracheal ring fracture were

recorded and compared. The presence of surgical emphysema at the site was also observed and chest X-ray

performed to check for tube position and pneumothorax.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

This study was powered on the basis of previous results showing an incidence rate of 30% for complications in

the surgical tracheostomy (Ben-Num, Altman, & Best, 2004). A sample size of 40 patients in each group was

calculated to detect a decrease in the incidence of complications down to 15% with =0.05 and =0.2. The

chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was applied to determine the differences in the occurrence of complications

between the groups. For continuous variables, student's t-test was applied to compare the data between the two

groups. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if p<0.05.

3. Results

Table 1. Demographic data and duration of procedure time for two study groups

Groups

PDT (n =40)

ST (n =40)

P value

Age (years)

35.2111.81

32.0812.63

0.09

Gender(F/M)

18/22

21/19

0.12

Duration of tracheostomy (min)

10.012.42

15.083.16

<0.001

Data are presented as meanSD or number of patients. PDT = percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy, ST = surgical

tracheostomy.

Table 2. Postoperative complications of blue rhino PDT and surgical tracheostomy

Complications

Pdt

St

P Value

No complication

25

27

0.09

Complication

15

13

0.12

Hypotension

0.08

Hypoxemia

<0.001

Tracheal ring fracture

Endotracheal tube puncture

<0.001

Cuff leak of tube

<0.001

Difficult tube placement

<0.001

Stomal infection

Minor bleeding

0.21

Major bleeding

<0.001

Death related to tracheostomy

Pneumothorax

Posterior wall injury

<0.001

Subcutaneous emphysema

Cardiac dysrhythmias

<0.001

False passage

<0.001

Data are presented as number. PDT= percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy, ST=surgical tracheostomy.

As shown in Table 1, a total of 40 patients were considered for PDT. In the PDT group, 22 cases were men and

18 women (M/F=22/18), with a mean age of 3511.8 years. Also, 40 patients were considered for surgical

tracheostomy including 19 men and 21 women (M/F=19/21) with a mean age equal to 3212.6. There was no

difference between the two groups in terms of age and sex (p>0.05). The procedure time as defined by the time

223

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs

Global Journal of Health Science

Vol. 6, No. 3; 2014

span from the first puncture of the trachea to the end of successful insertion of the tracheostomy tube and

connection to ventilator for PDT and ST groups was 10.012.42 minutes and 15.083.16 minutes, respectively.

All PDTs were performed without technical difficulties with the exception of one case in whom the procedure

was converted to surgical tracheostomy due to technical difficulty. There was no significant disturbance of vital

signs throughout the procedures. There was no death related to tracheostomy. Also, there was no stomal infection

in patients of the present study. Posterior tracheal wall injury and major bleeding were only observed in one

patient of PDT group and one case of ST group, respectively. Other complications such as tracheal ring fracture

and pneumothorax or death because of procedure were not observed in the patients of two groups. Table 2 shows

the comparison made between the post procedure outcomes for the PDT and surgical groups.

4. Discussion

Based on the data found in our study, it was concluded that PDT with blue rhino technique is a safe, quick, and

effective method and can be performed by an intensivist while the overall complication rate in both group was

comparable. In our study, the overall complication rate was 40% and the majority of complications were minor

and quickly improved. This was in contrast with the study by Siranovic and coworkers in which a complication

rate of 22.5% was reported (Cattano, Giunta, & Buzzigoli, 2006; iranovi et al., 2007). Meanwhile, despite the

long experience with ST, the overall complication rate of ST is still high. In surgical tracheostomy, the incidence

of local hemorrhage or stomal infection was reported to be around 37% (Cattano et al., 2006). However this

discrepancy between the results may be due to different population, physicians skill, and approach to procedures.

The mean procedure time of 10 minutes found in this study was similar to those demonstrated in previous reports

(Hinerman, Alvarez, Keller, 2000; Freeman, Isabella, Lin, & Buchman, 2000). On average, the time spent in

performing PDT was approximately 5 minutes less than ST. This resulted in a shorter duration and a lesser

chance of hypoxia during the procedure. This finding is consistence with the results of the study by Siranovic et

al in which PDT technique with Griggs method was associated with a shorter procedure time and lower

morbidity in comparison to the surgical technique (iranovi et al., 2007). Previous studies indicate that early

PDT-related complications include paratracheal insertion, posterior tracheal wall injury, major bleeding, and

pneumothorax (Freeman et al., 2000; Dongelmans et al., 2004; Tomsic et al., 2006). These complications,

however, were not found in our study. This might be due to the application of bronchoscopic guidance which

provided the operator with direct visual information, assuring the correct placement of tracheostomy and

avoiding possible complications and this is the main reason for recommending the use of bronchoscopic

guidance as a part attached to PDT by many authors (Oberwalder et al., 2004; Tomsic et al., 2006; Petros et al.,

1997).

In agreement to our study, Cantais, Kaiser, Le-Goff and Palmier (2002) also demonstrated that PDT is a safe

procedure to perform at the bedside. In general, PDT appears to be a less traumatic procedure and the skin

incision required in PDT is smaller than in ST. Furthermore, PDT requires tracheal opening (tracheostoma) by

dilation of the soft tissue space between the tracheal rings instead of direct cutting through cartilaginous ring as

in ST. Therefore, a lower incidence of tracheal stenosis at stomal site would be expected. Several studies have

shown the significant cost saving in western countries, however, the main limitation of PDT in Iran is the high

cost of the commercial kit.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our data suggest that PDT with blue rhino technique is a safe, quick, and effective method and can

be performed by an intensivist. Moreover, the overall complication rate in both groups was comparable, although

the procedure time was shorter in PDT. The main advantage of PDT is the possibility of its performance in ICU,

as a bedside procedure, which prevents the risk of transfer to the operating room. However, it is clear that the

simplicity and easiness of a technique shouldnt lead to an attitude that every physician is allowed to perform it.

PDT must be left in the hands of physicians with enough experience. Since there is some concern that the

evaluation of morbidity and outcomes of patients with a tracheostomy has not, at present, been adequately

investigated, further multi-center, large scale trials are needed to achieve a better conclusion.

References

Celli, B. R. (2012). Mechanical ventilator support. In Harrison T. R. et al. (eds.), Harrisons Principles of internal

medicine 18th (pp. 2214). USA: MC Graw Hill.

Ben-Num, A., Altman, E., & Best, L. E. (2004)Emergency percutaneous tracheostomy in trauma patients: an

early experience. Ann Thorac Surg, 11930, 1045-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.065

Boonsarngsuk, V., Kiatboonsri, S., & Choothakan, S. (2007). Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy with

224

www.ccsenet.org/gjhs

Global Journal of Health Science

Vol. 6, No. 3; 2014

broncoscopic guidance. J Med Assoc Thai, 90(8), 1512-7.

Byhahn, C., Wilke, H. J., Halbig, S., Lischke, V., & Westphal, K. (2000). Percutaneous tracheostomy: Ciaglia

blue

rhino

versus

the

basic

Ciaglia

technique.

Anesth

Analg,

91(4),

882-886.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200010000-00021

Cantais, E., Kaiser, E., Le-Goff, Y., & Palmier, B. (2002). Percutaneous tracheostomy: prospective comparison

of the transelaryngeal technique versus the forceps dilatational technique in 100 critically ill adults. Crit

Care Med, 30, 815-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200204000-00016

Cattano, D., Giunta, F., & Buzzigoli, S. (2006). Forceps dilatational percutaneous tracheostomy: safe and short.

Anaesth Intensive Care, 34(4), 523.

Ciaglia, P., Firsching, R., & Syniec, C. (1985). Elective percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy: a new simple

bedside procedure. Chest, 87(6), 715-719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.87.6.715

Dongelmans, D. A., van der Lely, A. J., Tepaske, R., & Schultz, M. J. (2004). Complications of percutaneous

dilatational tracheostomy. Crit Care, 8(5), 397-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc2903

Durbin, C. G. Jr. (2005). Techniques for performing tracheostomy. Respir care, 50(4), 448-9.

Durbin, C. G. Jr. (2005). Indications for and Timing of Tracheostomy. Respir care, 50(4), 483-7.

Freeman, B. D., Isabella, K., Lin, N., & Buchman, T. G. (2000). A meta-analysis of prospective trial comparing

percutaneous and surgical tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Chest, 118(5), 1412-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.118.5.1412

Ingenito Edward, P. (2008). Mechanical ventilator support. In T. R. Harrison et al. (eds.), Harrisons Principles of

internal medicine 17th (pp. 1684-1685). USA: MC Graw Hill.

Griffiths, J., Barber, V. S., Morgan, L., & Young, I. D. (2005). Systematic review and metaanalysis of studies of

the timing of the tracheostomy in adult patients undergoing artificial ventilation. BMJ, 330, 12430.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38467.485671.E0

Groves, D. S., & Durbin, C. G. Jr. (2007). Tracheostomy in the critically ill: indications, timing and techniques.

Curr Opin Crit Care, 13(1), 90-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0b013e328011721e

Oberwalder, M., Weis, H., Nehoda, H., Kafka-Ritsch, R., Bonatti, H., & Prommegger, R. (2004). Video

bronchoscopic guidance makes percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy safer. Surg Endosc, 18, 839-42.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-003-9082-0

Petros, S., & Engelmann, L. (1997). Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy in medical ICU. Intensive Care Med,

23(6), 630-4.

Porter, J. M., & Ivatury, R. R. (1999). Preferred route of tracheostomy--percutaneous versus open at the bedside.

A randomized prospective study in the surgical intensive care unit. Am Surg, 65(2), 142-6.

Rudr, A. (2002). Precutaneous tracheostomy. Update

http://www.nda.ox.ac.uk/wfsa/html/u15/u1516_01

in

anesthesia,

15,

16.

Retrieved

from

iranovi, M., Gopevi, S., Kelei, M., Kova, N., Kriki, V., Rode, B., & Vui, M. (2007). Early

complication of percutaneous tracheostomy using the Griggs method. Signa Vitae, 2(2), 18-20.

Tomsic, J. P., Connolly, M. C., Joe, V. C., & Wong, D. T. (2006). Evaluation of bronchoscopic assisted

percutaneous tracheostomy. Am Surg, 72(10), 970-2.

Young, D., Harrison, D. A., Cuthbertson, B. H., Rowan, K.; TracMan Collaborators. (2013). Effect of early vs

late tracheostomy placement on survival in patients receiving mechanical ventilation: the TracMan

randomized trial. JAMA, 309(20), 2121-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.5154

Copyrights

Copyright for this article is retained by the author(s), with first publication rights granted to the journal.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

225

Вам также может понравиться

- Clinical FormulationДокумент24 страницыClinical Formulationaimee2oo8100% (2)

- Anger Management For Teens: by Fredric Provenzano, PHD, NCSP Seattle, WaДокумент3 страницыAnger Management For Teens: by Fredric Provenzano, PHD, NCSP Seattle, WaJonathanKiehlОценок пока нет

- Lower Back Pain - MontaltoДокумент5 страницLower Back Pain - MontaltoElizabeth OxfordОценок пока нет

- Surgery 1.04 Surgical Diseases of The Thyroid GlandДокумент15 страницSurgery 1.04 Surgical Diseases of The Thyroid GlandjayaeroneОценок пока нет

- Occupation in Occupational Therapy PDFДокумент26 страницOccupation in Occupational Therapy PDFa_tobarОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Flail Chest.Документ6 страницJurnal Flail Chest.Dessy Christiani Part IIОценок пока нет

- Manual of Clinical Nutrition2013Документ458 страницManual of Clinical Nutrition2013Jeffrey Wheeler100% (9)

- ORTEGA P. S., Notes on the MiasmsДокумент90 страницORTEGA P. S., Notes on the MiasmsMd. Mahabub Alam100% (6)

- Online Job Application for Staff Nurse Position in UAEДокумент3 страницыOnline Job Application for Staff Nurse Position in UAEremzyliciousОценок пока нет

- OET Reading From U To VДокумент12 страницOET Reading From U To VLavanya Ranganathan93% (45)

- Transparency in Family Therapy: Guidelines and ConsiderationsДокумент20 страницTransparency in Family Therapy: Guidelines and ConsiderationsFausto Adrián Rodríguez López100% (1)

- Perioperative CareДокумент48 страницPerioperative CareBryan FederizoОценок пока нет

- Sample Nursing Interview Questions & TipsДокумент2 страницыSample Nursing Interview Questions & TipssamdakaОценок пока нет

- Hypnoth Rapy Training in Titut : Clinical Hypnotherapy CertificationДокумент7 страницHypnoth Rapy Training in Titut : Clinical Hypnotherapy CertificationsalmazzОценок пока нет

- Tracheostomy in The Intensive Care Unit A University Hospital in A Developing Country StudyДокумент5 страницTracheostomy in The Intensive Care Unit A University Hospital in A Developing Country StudycendyjulianaОценок пока нет

- Extending The Preoxygenation Period From 4 To 8 Mins in Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Emergency IntubationДокумент4 страницыExtending The Preoxygenation Period From 4 To 8 Mins in Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Emergency IntubationLuis ArdilaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal ARDSДокумент8 страницJurnal ARDSrifki yulinandaОценок пока нет

- Five Years Experience of Tracheostomy at A Tertiary Level Hospital (Dhaka Medical College Hospital) in Bangladesh Review of 257 CasesДокумент8 страницFive Years Experience of Tracheostomy at A Tertiary Level Hospital (Dhaka Medical College Hospital) in Bangladesh Review of 257 CasesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Egyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied SciencesДокумент5 страницEgyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied SciencesLuis De jesus SolanoОценок пока нет

- Minimally Invasive Perventricular Device Occlusion Versus Surgical Closure For Treating Perimembranous Ventricular Septal DefectДокумент10 страницMinimally Invasive Perventricular Device Occlusion Versus Surgical Closure For Treating Perimembranous Ventricular Septal DefectRinzyОценок пока нет

- Pda Ev Ejtcs 04Документ7 страницPda Ev Ejtcs 04emmanuel le bretОценок пока нет

- ACFrOgAB8 Tkw2cTNZ5H661ndcneV9fi1RTn1ykvnJvumEFlHYEvSpEHtoXIvYK5jjNGQbrB35rwgjvkxfQME3bphkaekY6xwI BQlK08W3zxE2v4uvQ7YrquWEUIv3SWl0RB VNAPF1WDhLtIIeДокумент6 страницACFrOgAB8 Tkw2cTNZ5H661ndcneV9fi1RTn1ykvnJvumEFlHYEvSpEHtoXIvYK5jjNGQbrB35rwgjvkxfQME3bphkaekY6xwI BQlK08W3zxE2v4uvQ7YrquWEUIv3SWl0RB VNAPF1WDhLtIIevinicius.alvarez3Оценок пока нет

- %pediatric TracheostomyДокумент25 страниц%pediatric TracheostomyFabian Camelo OtorrinoОценок пока нет

- A Comparative Study of Complic PDFДокумент6 страницA Comparative Study of Complic PDFBeatrice TanudjajaОценок пока нет

- With The Advance in The Techniques of Hemostasis Is It Necessary To Use Drain Routinely in Thyroid Surgery A Comparative StudyДокумент8 страницWith The Advance in The Techniques of Hemostasis Is It Necessary To Use Drain Routinely in Thyroid Surgery A Comparative StudyAthenaeum Scientific PublishersОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S1010518222001743 MainДокумент5 страниц1 s2.0 S1010518222001743 MainOttofianus Alvedo Hewick KalangiОценок пока нет

- Use of Port-A-Cath in Cancer Patients: A Single-Center ExperienceДокумент7 страницUse of Port-A-Cath in Cancer Patients: A Single-Center ExperienceLydia AmaliaОценок пока нет

- JPNR Igel Vs ETT ArticleДокумент7 страницJPNR Igel Vs ETT ArticleBhavikaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal 3Документ5 страницJurnal 3Caesar RiefdiОценок пока нет

- Timing of Tracheostomy in Patients With Prolonged Endotracheal Intubation: A Systematic ReviewДокумент12 страницTiming of Tracheostomy in Patients With Prolonged Endotracheal Intubation: A Systematic ReviewCassie AbernathОценок пока нет

- Jnic 2019 00213 PDFДокумент6 страницJnic 2019 00213 PDFAwal13 ArigaОценок пока нет

- A Study On Complications of Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Surgery in Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, NepalДокумент4 страницыA Study On Complications of Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Surgery in Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, NepalHaziq AnuarОценок пока нет

- Outpatient Tympanomastoidectomy: Factors Affecting Hospital AdmissionДокумент4 страницыOutpatient Tympanomastoidectomy: Factors Affecting Hospital AdmissionGuillermo StipechОценок пока нет

- Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve ReplacementДокумент11 страницMinimally Invasive Aortic Valve ReplacementDm LdОценок пока нет

- Lansford 2007Документ6 страницLansford 2007Danielle Santos RodriguesОценок пока нет

- Bmri2016 3741426Документ7 страницBmri2016 3741426MandaОценок пока нет

- Anaesthesia For Adenotonsillectomy: An Update: Indian J Anaesth 10.4103/0019-5049.199855Документ14 страницAnaesthesia For Adenotonsillectomy: An Update: Indian J Anaesth 10.4103/0019-5049.199855Nazwa AlhadarОценок пока нет

- (2013) Surgical Treatment of Severe EpistaxisДокумент6 страниц(2013) Surgical Treatment of Severe EpistaxisBang mantoОценок пока нет

- Airway StentДокумент5 страницAirway StentYanuar AbdulhayОценок пока нет

- Impact of Postoperative Morbidity On Long-Term Survival After OesophagectomyДокумент10 страницImpact of Postoperative Morbidity On Long-Term Survival After OesophagectomyPutri PadmosuwarnoОценок пока нет

- ThoraventДокумент7 страницThoraventadamОценок пока нет

- Medip, IJOHNS-388 OДокумент6 страницMedip, IJOHNS-388 Onaveed gulОценок пока нет

- KumarasingheДокумент4 страницыKumarasingheVitta Kusma WijayaОценок пока нет

- 247 FullДокумент6 страниц247 FullDhita Kemala RatuОценок пока нет

- HemoptisisДокумент7 страницHemoptisiswiliaОценок пока нет

- 12Hiệu quả mở kq sớm pt gộp 2015Документ10 страниц12Hiệu quả mở kq sớm pt gộp 2015Cường Nguyễn HùngОценок пока нет

- Ent 1 2 3Документ9 страницEnt 1 2 3naveed gulОценок пока нет

- Recruitment Maneuver in Prevention of Hypoxia During Percutaneous Dilational Tracheostomy: Randomized TrialДокумент7 страницRecruitment Maneuver in Prevention of Hypoxia During Percutaneous Dilational Tracheostomy: Randomized TrialMelly Susanti PhuaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal AnestesiДокумент5 страницJurnal AnestesiHabibah Nurla LumiereОценок пока нет

- Fibrinolytic Treatment of Complicated Pediatric TДокумент2 страницыFibrinolytic Treatment of Complicated Pediatric TDR GURDEEP SINGHОценок пока нет

- Use of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy To Prevent Desaturation During Tracheal Intubation of Intensive Care Patients With Mild-to-Moderate HypoxemiaДокумент10 страницUse of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy To Prevent Desaturation During Tracheal Intubation of Intensive Care Patients With Mild-to-Moderate HypoxemiaLingga AniОценок пока нет

- Surgical Management of Benign Acquired Tracheoesophageal Fistulas- A Ten-Year Experience Bibas 2016Документ7 страницSurgical Management of Benign Acquired Tracheoesophageal Fistulas- A Ten-Year Experience Bibas 2016vinicius.alvarez3Оценок пока нет

- Techniques of Surgical TracheostomyДокумент10 страницTechniques of Surgical TracheostomyMhd Al Fazri BroehОценок пока нет

- Obesity and Anticipated Difficult Airway - A Comprehensive Approach With Videolaryngoscopy, Ramp Position, Sevoflurane and Opioid Free AnaesthesiaДокумент8 страницObesity and Anticipated Difficult Airway - A Comprehensive Approach With Videolaryngoscopy, Ramp Position, Sevoflurane and Opioid Free AnaesthesiaIJAR JOURNALОценок пока нет

- Original ArticleДокумент9 страницOriginal ArticleJason HuangОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Open Closed Suction GelartiДокумент9 страницJurnal Open Closed Suction GelartiAyahe Bima MubarakaОценок пока нет

- Anesthesia Management in Respiratory DepressionДокумент7 страницAnesthesia Management in Respiratory DepressionGandita AnggoroОценок пока нет

- Posttrx Empyema PDFДокумент6 страницPosttrx Empyema PDFAndyGcОценок пока нет

- IcuДокумент56 страницIcurulli_pranandaОценок пока нет

- 241 TracheostomyДокумент12 страниц241 Tracheostomyalbert hutagalungОценок пока нет

- s13049 019 0599 1 PDFДокумент9 страницs13049 019 0599 1 PDFDeby WicaksonoОценок пока нет

- Comparison of The Short-Term Outcomes of Using DST and PPH Staplers in The Treatment of Grade Iii and Iv HemorrhoidsДокумент7 страницComparison of The Short-Term Outcomes of Using DST and PPH Staplers in The Treatment of Grade Iii and Iv HemorrhoidsdianisaindiraОценок пока нет

- 2022-10# (PEERJ) RR in ECMOДокумент17 страниц2022-10# (PEERJ) RR in ECMOjycntuОценок пока нет

- Jurnal KardioДокумент5 страницJurnal KardiomadeОценок пока нет

- Comparative Study Between Hydrostatic and Pneumatic Reduction For Early Intussusception in PediatricsДокумент6 страницComparative Study Between Hydrostatic and Pneumatic Reduction For Early Intussusception in PediatricsMostafa MosbehОценок пока нет

- JTD 12 10 6023Документ7 страницJTD 12 10 6023sepputriОценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of Treatment With High-Frequency Chest Wall Oscillation in Patients With BronchiectasisДокумент8 страницEffectiveness of Treatment With High-Frequency Chest Wall Oscillation in Patients With BronchiectasisfarahОценок пока нет

- Predictionof Difficult AirwayДокумент6 страницPredictionof Difficult AirwayjemyОценок пока нет

- Kali Bichromicum 30C For COPD 2005Документ8 страницKali Bichromicum 30C For COPD 2005Dr. Nancy MalikОценок пока нет

- The Changing Role For Tracheostomy in Patients Requiring Mechanical VentilationДокумент11 страницThe Changing Role For Tracheostomy in Patients Requiring Mechanical VentilationGhost11mОценок пока нет

- 508 - 7 CardiologyДокумент9 страниц508 - 7 CardiologymlinaballerinaОценок пока нет

- Anesthesia in Thoracic Surgery: Changes of ParadigmsОт EverandAnesthesia in Thoracic Surgery: Changes of ParadigmsManuel Granell GilОценок пока нет

- Length/height-For-Age BOYS: Birth To 5 Years (Z-Scores)Документ1 страницаLength/height-For-Age BOYS: Birth To 5 Years (Z-Scores)Malisa LukmanОценок пока нет

- CC 13085Документ9 страницCC 13085Teuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- DHF - DinkesДокумент31 страницаDHF - DinkesAlfindraHaidaNabilaОценок пока нет

- JurnalДокумент12 страницJurnalIrara RaОценок пока нет

- Keyword Aggressive BehaviourДокумент40 страницKeyword Aggressive BehaviourTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Tabel Kebutuhan Gizi 2Документ1 страницаTabel Kebutuhan Gizi 2Teuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Homeblockcoin: Roadmap 2018 UpdatesДокумент3 страницыHomeblockcoin: Roadmap 2018 UpdatesTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- PA Personality Inventory AssessmentДокумент12 страницPA Personality Inventory AssessmentTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Length/height-For-Age BOYS: Birth To 5 Years (Z-Scores)Документ1 страницаLength/height-For-Age BOYS: Birth To 5 Years (Z-Scores)Malisa LukmanОценок пока нет

- Reference 2Документ5 страницReference 2Teuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Jurnal ImanudinДокумент22 страницыJurnal ImanudinTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Breaker ZДокумент6 страницBreaker ZM Arif BudimanОценок пока нет

- Tracheostomy Procedures in The Intensive Care Unit: An International SurveyДокумент10 страницTracheostomy Procedures in The Intensive Care Unit: An International SurveyTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Aggressive BehaviourДокумент56 страницAggressive BehaviourTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Pathogenesis and Clinical FeaturesДокумент30 страницSystemic Lupus Erythematosus: Pathogenesis and Clinical FeaturesOrion JohnОценок пока нет

- Jadwal Jaga Malam JuniorДокумент6 страницJadwal Jaga Malam JuniorTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- PCL Jurnal 2Документ4 страницыPCL Jurnal 2Teuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Ingested Foreign BodyДокумент18 страницIngested Foreign BodyTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- PCL JurnalДокумент8 страницPCL JurnalTeuku FaisalОценок пока нет

- Guidelines TBC TerbaruДокумент160 страницGuidelines TBC TerbaruSutoto MoeljadiОценок пока нет

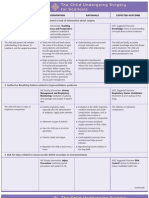

- NURSING CARE PLAN The Child Undergoing Surgery For ScoliosisДокумент3 страницыNURSING CARE PLAN The Child Undergoing Surgery For ScoliosisscrewdriverОценок пока нет

- NICU ReportДокумент7 страницNICU ReportoapsdoaksdokaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 017Документ18 страницChapter 017wn4tb100% (2)

- 2 - Ospina 2007 ArqДокумент472 страницы2 - Ospina 2007 ArqMarcia KoikeОценок пока нет

- Screenshot 2022-12-14 at 4.16.40 PMДокумент1 страницаScreenshot 2022-12-14 at 4.16.40 PMPrisha SoniОценок пока нет

- Neuro-pharmacological and analgesic effects of Arnica montana extractДокумент4 страницыNeuro-pharmacological and analgesic effects of Arnica montana extractCristina Elena NicuОценок пока нет

- 6 - B.arun., Safety Positions For Healthy Sex Following Back PainДокумент5 страниц6 - B.arun., Safety Positions For Healthy Sex Following Back PainDr. Krishna N. SharmaОценок пока нет

- Public School Teachers Awareness On ADHD Survey FormДокумент3 страницыPublic School Teachers Awareness On ADHD Survey Formchichur jenОценок пока нет

- Ventilator Associated PneumoniaДокумент2 страницыVentilator Associated PneumoniaMuzana DariseОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Enzim AmilaseДокумент6 страницJurnal Enzim AmilaseTriRatnaFauziahОценок пока нет

- Stem Cell Research PaperДокумент3 страницыStem Cell Research Papermyrentistoodamnhigh100% (1)

- 6 Back Massage Pressure Points For Relaxation and Stress Relief PDFДокумент9 страниц6 Back Massage Pressure Points For Relaxation and Stress Relief PDFلوليتا وردةОценок пока нет

- Analgesia y ElectroacupunturaДокумент8 страницAnalgesia y ElectroacupunturaagustinОценок пока нет

- Schizoaffective With Bipolar DisordersДокумент14 страницSchizoaffective With Bipolar DisordersNaomi MasudaОценок пока нет

- 5 Tecar Vs Ultrasound 100 Patient Series - Double Blinded and Randomised - University of ValenciaДокумент37 страниц5 Tecar Vs Ultrasound 100 Patient Series - Double Blinded and Randomised - University of ValenciaSilvia PluisОценок пока нет

- Newsletter SY 2012-2013Документ8 страницNewsletter SY 2012-2013Lorma HighlightsОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Sociology - 1ST Canadian Edition: Chapter 19. Health and MedicineДокумент36 страницIntroduction To Sociology - 1ST Canadian Edition: Chapter 19. Health and MedicineChudhry RizwanОценок пока нет