Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Crossfunctional Alignment

Загружено:

mesay83Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Crossfunctional Alignment

Загружено:

mesay83Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258641803

Solution business models: Transformation

along four continua

Article in Industrial Marketing Management July 2013

DOI: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.05.008

CITATIONS

READS

38

401

4 authors:

Kaj Storbacka

Charlotta Windahl

University of Auckland Business School

University of Auckland

49 PUBLICATIONS 2,642 CITATIONS

13 PUBLICATIONS 550 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Suvi Nenonen

Anna Salonen

University of Auckland

University of Turku

18 PUBLICATIONS 414 CITATIONS

5 PUBLICATIONS 101 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate,

letting you access and read them immediately.

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Kaj Storbacka

Retrieved on: 14 October 2016

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached

copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elseviers archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights

Author's personal copy

Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Industrial Marketing Management

Solution business models: Transformation along four continua

Kaj Storbacka a,, Charlotta Windahl a, 1, Suvi Nenonen b, 2, Anna Salonen c, 3

a

b

c

University of Auckland Business School, Department of Marketing, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand

Hanken School of Economics, Department of Marketing, University of Auckland Business School, Graduate School of Management, P.O. Box 479, FIN-00101 Helsinki, Finland

Aalto University School of Business, Department of Information and Service Economy, P.O. Box 21210, FI-00076 Aalto, Finland

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 31 January 2012

Received in revised form 26 January 2013

Accepted 23 April 2013

Available online 2 June 2013

Keywords:

Business model

Solution business

Transformation

a b s t r a c t

Using a business model perspective, we identify four continua that are of specic relevance for industrial rms

transforming toward solution business models: customer embeddedness, offering integratedness, operational

adaptiveness, and organizational networkedness. Using these continua, we explore the opportunities and challenges related to solution business model development in two different business logics that are of particular importance in an industrial context: installed-base (IB) and input-to-process (I2P). The paper draws on eight

independent research projects, spanning an eleven-year period, involving a total of 52 multinational enterprises.

The ndings show that the nature and importance of the continua differ between the I2P and IB business logics.

IB rms can almost naturally transition toward solutions, usually through increasing customer embeddedness

and offering integratedness, and then by addressing issues around the other continua. For I2P rms, the changes

needed are less transitional. Rather, they have to completely change their mental models and address the development needs on all continua simultaneously.

2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Servitize, move forward in the value chain, and transform your

product business model into a solution business model! Industrial

rms are urged to consider that the product is dead (Phillips, Ochs,

& Schrock, 1999, p. 51) and they need to manage the transition from

products to services (Oliva & Kallenberg, 2003, p.160), and make solutions the answer (Foote, Galbraith, Hope, & Miller, 2001, p.1), because

however difcult the transition, manufacturers can't afford to ignore

the opportunities that lie downstream (Wise & Baumgartner, 1999,

p.141).

When companies take so called servitization (Vandermerwe &

Rada, 1988) steps toward solutions, they concurrently change their

earning logic, move their position in the value network, and need to

use and develop capabilities in a different way inherently making fundamental business model changes. Nevertheless, though many scholars

implicitly encourage a change of business models, few explicitly address

challenges in developing and implementing solution business models

(Baines, Lightfoot, Benedettini, & Kay, 2009).

4th and Final Submission to Industrial Marketing Management Special Issue: Business

models exploring value drivers and the role of marketing.

Corresponding author. Tel.: +64 99237213.

E-mail addresses: k.storbacka@auckland.ac.nz (K. Storbacka),

c.windahl@auckland.ac.nz (C. Windahl), suvi.nenonen@hanken. (S. Nenonen),

anna.salonen@aalto. (A. Salonen).

1

Tel.: +64 99236301.

2

Tel.: +358 505626028.

3

Tel.: +358 403538338.

0019-8501/$ see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.05.008

In this paper, we argue that using a business model lens when analyzing solution business is important for two reasons. First, it highlights

the challenges associated with the transformation toward solution business model (c.f. Demil & Lecocq, 2010). Few rms actually make a complete transformation from a product business to a solution business

they have part of their activities focused on solution business, whilst

building on their existing product business. Many of them will end up

having parallel business models (Markides & Charitou, 2004). This implies that solution business models are not static and that the transformation needs to be seen in terms of degrees of change. Even though

previous research highlights the importance of developing new solution

business models (c.f., Storbacka, 2011), there is lack of research related

to the transformational needs in various business model dimensions

(Kapletia & Probert, 2010).

Second, a business model approach facilitates a comparison across

different business contexts. This is relevant as solution business is

predisposed by particular industry conditions (Pisano, 2006; Storbacka,

2011), commonly accepted dominant designs (Baldwin & Clark, 2006;

Srinivasan, Lilien, & Rangaswamy, 2006), or industry recipes (Spender,

1989). There are, however, few specic guidelines and tools for developing solution business in different industrial or business contexts (Baines

et al., 2009). Rather, existing research tends to treat solution providers as

a homogenous group, which has led to calls for further research that go

beyond recommending broad reaching solution strategies and capabilities for solution suppliers (Kapletia & Probert, 2010).

This paper addresses the above identied gaps by focusing on

the following two research questions: (1) how do business models

need to change when rms transform toward solution business,

and (2) how do the opportunities and challenges for implementing

Author's personal copy

706

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

solution business models differ between industrial contexts? More

specically, the paper focuses on the two generic business logics

(Nenonen & Storbacka, 2010) of particular importance in a

business-to-business, industrial context: installed-base (IB) and

input-to-process (I2P). Firms operating with IB logic provide

investment goods, thus creating an installed base at the customers.

IB logic is common among rms representing machinery and equipment industries. The I2P logic is relevant for rms that provide goods

that are utilized as inputs in the customers' process. The good is

transformed during the customer's process in such a way that it

ceases to exist as a separate entity. I2P rms are found in industries

such as metal, pulp and paper, and utilities.

We address the two research questions with an abductive research

process, drawing simultaneously on the emerging body of business

model research, on literature in the solution business area, as well as

on empirical research.

2. A synthetizing research process

This paper draws on data collected from eight independent research

projects spanning an eleven-year period (20012011) and involving a

total of 52 multinational enterprises from various industries. Most of

the rms are headquartered in Finland, the Netherlands, or Sweden.

The industries represented include adhesion and surfacing solutions,

cargo handling systems, chemicals, construction, compressors, construction materials, copper tubes, elevator and escalators, energy, digital printing, electronic manufacturing services, uid handling and

separation, forklift trucks, industrial machinery, information technology

services, metals, mining and construction equipment, mobile software

solutions, network infrastructure, oil rening, pumps, pulp and paper,

real estate, shipbuilding, and telecommunications.

Six of the research projects were consortium-based, i.e., they involved groups of seven to twelve rms in a six to nine month process,

where the focus was on investigating various aspects of solution business models: e.g., business model innovation, solution sales, industrialization of solutions, and growth through solution business. Two of the

research projects focused on a limited number of rms and on longitudinal aspects of solution transformation.

Altogether, the projects included 216 in-depth interviews, and 15

one-day workshops within the consortia groups. The workshops involved a total of 151 managers with an extensive experience of, and

interest in solution business. Synthesizing the ndings from these

projects provides opportunities to better understand the complex

phenomenon of solution business model development as applied

across different empirical contexts.

Detailed methodologies of the individual research projects have

been reported in nine previously published studies (Salonen, 2011;

Salonen, Gabrielsson, & Al-Obaidi, 2006; Storbacka, 2011; Storbacka

& Nenonen, 2009; Storbacka, Polsa, & Sksjrvi, 2011; Storbacka,

Ryals, Davies, & Nenonen, 2009; Windahl, 2007; Windahl & Lakemond,

2006, 2010). Thus, we do not discuss them in detail in this paper,

but rather provide an overview of how the empirical data was

synthetized in the process leading to this paper.

The synthesizing research process focused on interpretation and

reection rather than on the collection and processing of data

(Alvesson & Skoldberg, 2005). The nature of the research process

was abductive, combining induction and deduction (Locke, 2010).

Thus, it can be characterized as a non-linear, non-sequential, iterative

process of systematic and constant movement between the empirical

data, the model and the literature, during which the analytical frameworks were reoriented as directed by empirical ndings (Dubois &

Gadde, 2002). In a reective process such as this, the aim is to combine

elements in order to establish emergent patterns, and rene the constructs used to portray reality (Eisenhardt, 1989).

The process of synthetizing was governed by a set of principles that

the researchers adhered to using criteria from interpretive research and

grounded theory (see also Flint, Woodruff, & Fisher Gardial, 2002).

Drawing on Lincoln and Guba (1985), Miles and Huberman (1994),

Spiggle (1994), Strauss and Corbin (1990), and Wallendorf and Belk

(1989), conformability, integrity, pre-understanding and dependability

were dened as the main governing principles.

In order to reduce researcher bias (conformability or objectivity)

and ensure that the results are acceptable representation of the data

(integrity or authenticity), the research process was based on a

three-stage series of interactions between the researchers.

The rst stage focused on articulating the researchers' preunderstanding (Normann, 1977) built on the previous research reports

and the fact that all researchers have had a long term (515 years) research interest in the solution business area. Additionally, two of the researchers also have 10+ years of experience from consulting in this

area. This conrmed that there are differences between diverse business logics, and identied that the business model transformations,

which rms moving into solutions were engaging in, could be analyzed

using four continua.

During the second stage the researchers substantiated and described

business model transformations using the four continua as a lens. In

order to secure dependability, reliability, or auditability, the research

process utilized triangulation (Creswell & Miller, 2000; Denzin, 1978;

Stake, 1995). Triangulation was a natural starting point as none of the

researchers had participated in all the nine research projects. Furthermore, the four researchers had not worked in a joint research process

before. Three forms of triangulation were used: (1) data triangulation

(the empirical data in the underlying studies was collected through

several sampling strategies, data was collected at different times

and social situations, as well as on a variety of rms and contexts),

(2) methodological triangulation (more than one method was used for

gathering data: interviews, interactive workshops with practitioners,

and observations), and (3) investigator triangulation (more than one

researcher interpreted the data). As a result the process produced consistency of explanations between researchers and research contexts.

During the third stage the focus was on synthetizing and validating

the ndings, a process that continued throughout the writing of the

paper. This was done by a continued interaction between the empirical

data and literature. In doing so it was noted that more literature support

could be found for the business model continua, whereas the business

logics characteristics pre-dominantly emerged from the empirical material. During the entire process all researchers were active participants

and knowledge was constructed collaboratively as interpretations were

altered, expanded and rened.

Due to the unusually large amount of data and the explicit aim to

synthesize, we do not report ndings for individual case rms, nor do

we report intermediary results or direct quotes by the rm representatives. Instead, our narrative focuses on important similarities within

and differences across the empirical contexts.

3. Transforming toward solution business models along four

continua

In this section we propose that a deeper understanding of the preconditions to success in solution business can be gained by using a business

model lens. We address our rst research question (how do business

models need to change when rms transform toward solution business),

by identifying four generic business model continua that can be used to

describe the transformation toward solution business models.

3.1. Applying a business model lens on solution business

Given the wide range of solution literature streams (Baines et al.,

2009; Fisher, Gebauer, & Fleish, 2012; Lay, Schroeter, & Biege, 2009;

Windahl & Lakemond, 2010), it becomes difcult to arrive at a xed

denition for the term solution (Evanschitzky, von Wangenheim, &

Woisetschlger, 2011). The denitions that do exist vary depending

Author's personal copy

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

on the scope of the offering, the type of elements integrated, or the

type of industries studied.

In this paper, we apply a process-oriented view whereby solutions

are dened as longitudinal, relational processes that comprise the joint

identication and denition of value creation opportunities, the integration and customization of solution elements, the deployment of these

elements into the customer's process, and various forms of customer support during the delivery of the solution (Storbacka, 2011; Tuli, Kohli, &

Bharadwaj, 2007). This process-oriented denition implies that rms

can develop a range of different types of solutions, and that rms selling and delivering solutions will need to change many aspects of their

business model simultaneously.

Consequently, this denition has links to business model literature. First, it suggests that a transformational and dynamic view on

solution business models is needed (c.f. Demil & Lecocq, 2010;

Winter & Szulanski, 2001). We argue that it is less important to identify the static elements of a business model focus should be on the

dynamics of how rms develop their business models. Second, it

emphasizes the value creation taking place for the customer and the

supplier. Nenonen and Storbacka (2010) found that value creation

to customers and value capture for the rm are the two most common elements in existing business model denitions. Furthermore,

the business model concept is argued to be externally oriented and

depicts the relationships that rms have with a variety of actors in

their value networks, thus capturing the change toward networked

value creation (Teece, 2010; Zott & Amit, 2008).

Drawing on Mason and Spring (2011), Storbacka, Frow, Nenonen,

and Payne (2012), and Zott and Amit (2010), we use customers, offerings,

operations, and organization as generic continua along which business

model transformation materializes. Reconciling literature proposing

that business models are systemic congurations by nature (Teece,

2010; Tikkanen, Lamberg, Parvinen, & Kallunki, 2005) and literature emphasizing the transformational and dynamic nature of business models

(Demil & Lecocq, 2010; Winter & Szulanski, 2001), we propose that

rms that engage in solution business over time need to change their

business models in all these four continua, by taking various forms of

development steps that are likely to be interdependent.

First, rms aim at customer embeddedness: they target selected

customers and become embedded in their situations and processes

in order to support the customers in their value creating process

(Payne, Storbacka, & Frow, 2008). Second, rms increase their offering

integratedness: they integrate technical, business, and system elements,

and as a result, aim at changing their earning logic to increase value capture. Third, rms focus on operational adaptiveness: in order to exibly

and cost-effectively adapt to the customers' processes, rms need to

apply modular thinking in their operational processes. Finally, rms

aim at organizational networkedness: rms orchestrate a network of

actors that provide solution elements to selected customers, thereby

inuencing value creating opportunities in the larger network. In the

following sections we discuss the solution business model transformation along the identied continua. The identied solution business

model transformation continua are illustrated in Fig. 1.

3.2. Customer embeddedness

The customer embeddedness continuum refers to a key result of providing solutions, i.e., that the relationships with customers become relational and long term (Spring & Araujo, 2009; Vargo & Lusch, 2008). The

solution is developed, sold and delivered through a long-term process

with the customer rather than to the customers, i.e., value creation has

to be understood through the eyes of the customers (Brady, Davies, &

Gann, 2005; Davies, 2004). Increasing degrees of embeddedness has

profound impacts on the capabilities required, in terms of engagement

processes, the ability to deliver the agreed performance longitudinally,

and measurements used to measure success (Brady et al., 2005; Day,

2011; Storbacka, 2011).

707

Fig. 1. Solution business model continua.

It has, however, been shown that not all customers are willing to accept this transformation toward increased embeddedness and a different view on value creation (Kowalkowski, 2011), and focusing efforts

on such customers may not be efcient. Hence, the rm has to dene

focus markets, segments, and customers for the solution business, and

develop segment specic strategies, including business goals (Cornet et

al., 2000; Foote et al., 2001; Miller, Hope, Eisenstat, Foote, & Galbraith,

2002). To achieve increased embeddedness, rms need to be able to

make segment and customer specic value propositions (Anderson &

Narus, 1991), which are unique and linked to critical business concerns

of the customers.

Some authors argue that it is important to target the customers'

non-core activities as this will facilitate their focus on more promising

business activities (Ehret & Wirtz, 2010). In contrast, getting paid for

the new value created may be difcult if the solution does not target

customers' core activities, as the value of non-core activities is likely

to be less appreciated.

Ideally, a solution provider needs to create new capabilities to

cover a more strategically focused agenda, e.g., by applying a strategic

account management program. It becomes important to both identify

business issues of concern to the customer's top management that are

too complex for the customer rm to address, and show tangible

business results (Lay, Hewlin, & Moore, 2009; Shepherd & Ahmed,

2000).

3.3. Offering integratedness

The offering integratedness continuum refers to the integration of

offering components, i.e., that a customer cannot unbundle the solution and buy the elements separately (Johansson, Krishnamurthy, &

Schlissberg, 2003). Solutions are often discussed as integrated systems

of several inter-dependent goods, service, systems, and knowledge elements creating value beyond the sum of its parts (Johansson et al.,

2003; Roegner, Seifert, & Swinford, 2001).

When a rm increases the level of integration and customization, it

ultimately assumes the role of a performance provider whereby it manages the customer's technical operations and long-term system optimization (Helander & Mller, 2007). This position requires deep knowledge of

the customer's industrial processes and typically involves creating new

value propositions and pricing mechanisms based on performance improvement (Stremersch, Wuyts, & Frambach, 2001). The earning logic

changes from discrete cash ows (from selling products and/or services

on a transactional basis) toward continuous cash ows (toward selling

longitudinal, relational solutions).

The offering dimension is the most (implicitly) discussed business

model dimension in the solution literature. Different authors and research streams emphasize different integration and transition paths

(Baines et al., 2009; Matthyssens & Vandenbempt, 2008; Tukker &

Tischner, 2006). For example, authors focused on system integration

often emphasize turnkey solutions (e.g., Davies, 2004; Davies, Brady,

& Hobday, 2006); whereas authors discussing so called service

Author's personal copy

708

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

transition strategies (Fang, Palmatier, & Steenkamp, 2008) often emphasize increasingly advanced support services (e.g., Oliva &

Kallenberg, 2003). However, as stated in the introduction, with

some exceptions (see e.g., Matthyssens & Vandenbempt, 2008), few

authors discuss how the opportunities and challenges of integration

differ across contexts or business logics. In addition, as many rms

make a slow transition toward having only a certain part of their activities focus on solution business, the question of what level of

integratedness to aim for becomes crucial.

3.4. Operational adaptiveness

The operational adaptiveness continuum refers to the need to adapt

solutions (from development throughout delivery) to the customer's

situation and processes. The ability to create customer specic solutions

requires an approach based on modular thinking (Baldwin & Clark,

2000; Yigit & Allahverdi, 2003), which inuences both market facing

and operational processes (Meier, Roy, & Seliger, 2010). Firms need to

be able to respond to changing requirements rapidly, and at the same

time secure scalability and repeatability of solutions (Salonen, 2011;

Storbacka, 2011).

To support modularity, it becomes necessary to develop effective

information and knowledge management practices (Arnett &

Badrinarayanan, 2005; Johnstone, Dainty, & Wilkinson, 2009; Leigh

& Marshall, 2001; Pawar, Beltagui, & Riedel, 2009). For instance,

standardized solution modules can be digitalized into the rm's enterprise resource planning (ERP), or product data management

(PDM) system (Storbacka, 2011). To link customer specic value

propositions to efcient delivery, rms usually have conguration

tools (Meier et al., 2010) that help them to congure relevant customer

specic solutions. These tools can be used by customer facing units in

order to mix and match solution modules into combinations suitable

for the customers' situations (Davies et al., 2006). Solution congurators

are a key for the economies of repetition (Davies & Brady, 2000) as they

enable exible conguration of customer solutions and simultaneously

secure efcient delivery.

In order to excel in solution business and achieve economic viability,

it becomes important to balance the activity of integrating components

and tailoring solutions to specic customers with the need to create repeatable solutions (Foote et al., 2001; Shepherd & Ahmed, 2000), which

requires investments into new organizational capabilities (Storbacka,

2011).

3.5. Organizational networkedness

Progress along the organizational networkedness continuum implies that actors within the solution business network become increasingly dependent on each other's processes and activities, which

requires process harmonization across and within organizational

boundaries (Brady et al., 2005; Oliva & Kallenberg, 2003).

When it comes to managing internal challenges, the literature suggests different approaches. Some authors emphasize the need for separation, others the need for interaction and integration. In order to develop

new capabilities and enable experimentation with solution activities,

organizational separation might be needed; for example through separating the service department (Oliva & Kallenberg, 2003), or through

managing project-based solution initiatives in a separate unit (Davies &

Brady, 2000). However, in order to sustain and create repeatable solutions, there is a need to create mechanisms for interaction and integration between different organizational parts of the company (Gann &

Salter, 2000; Storbacka, 2011). Solution business needs input across departmental units, such as research and development, service and operations. The front-end's pull for customization needs to be balanced with

the back-end's push for standardization (Davies et al., 2006; Galbraith,

2002a).

When it comes to external challenges, rms need to recognize the

importance of cooperation with partners and suppliers. A rm that

develops its solution business based on a genuinely customer oriented

viewpoint will end up redening itself from a producer to a provider;

i.e., a provider does not produce everything that it provides. A solution

delivery should not be seen only as a dyadic exchange between provider

and customer, but rather as a collaborative effort among several actors in

a value network (Davies, 2004; Davies, Brady, & Hobday, 2007; Ivens,

Pardo, Salle, & Cova, 2009; Ulaga & Eggert, 2006; Windahl &

Lakemond, 2006). This external network contributes to the range of capabilities and good elements that can be integrated to create value for

customers (Galbraith, 2002b).

3.6. Creating congurational t between the continua

The above discussion draws attention to a number of considerations

for rms moving toward solution business. It illustrates that solution

business models are not static, nor is the transformation complete. It

is more a question of degrees of change taking place along the four interrelated continua. This ts well with the transformational approach

to business models (Demil & Lecocq, 2010) which suggests that the

business model concept can be especially useful in addressing change.

Building on this, we propose that the identied continua represent the

overriding change directions that rms move along when they develop

their solution business. There are various degrees of change that rms

can choose to take, and by combining different degrees of change on

the different continua, rms will end up with different solution business

models.

Even though different rms make diverse decisions on how far to

progress on each solution business model continua, the continua are

interrelated and interdependent (as illustrated in Fig. 2). Therefore,

the development steps taken along one continuum may necessitate

a change in the other continua as well. For example, the level of offering

integratedness will affect the possibilities for co-creation of value with

the customers (i.e., customer embeddedness), the need for partnering

with actors in the business network (i.e., organizational networkedness),

and the opportunities for customization, modularity and repeatability

(i.e., operational adaptiveness).

This ts well with the argument that business models are systemic

congurations by nature (Teece, 2010; Tikkanen et al., 2005) and with

Miller's (1996, p. 509) argument that congurations can be dened

as the degree to which an organization's elements are orchestrated

and connected by a single theme (such as solution business). A key

objective of congurations is to create harmony, consonance, or t

between the elements (Meyer, Tsui, & Hinings, 1993; Miller, 1996;

Normann, 2001). Thus, it can be said that effective solution business

Fig. 2. Solution business model continua are interrelated and interconnected.

Author's personal copy

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

models are characterized by congurational t between elements on the

continua, which implies a need for several iterations until a sufcient degree of t has been achieved.

Congurations are characterized by equinality (Doty, Glick, &

Huber, 1993), indicating that several congurations may be equally

effective, as long as there is a high degree of congurational t. This implies that several solution business model designs can create equally

good end results (in terms of value creation) as long as the business

model ts the actor and its context. Consequently, we argue that it is

especially important for rms to understand the context in which the

solution business model is to be implemented.

4. Solution business models in different business logics

In this section we address our second research question: how the

opportunities and challenges for implementing solution business

models differ between industrial contexts. During the research process,

as the empirical data was revisited and interpretations were altered and

rened, it became evident that rms operating in certain industries

shared common challenges. As a result, we adopted Nenonen and

Storbacka's (2010) suggestion that business-to-business rms apply generic business logics (c.f., Hagel & Singer, 1999; Johnson, 2010). They

identify ve business logics: installed-base (investment goods creating

an installed base), input-to-process (goods that are utilized as input in

the customers' process), continuous relationships (services characterized

by long-term contracts); consumer-brands (products for the consumer

market that are sold through a channel); and situational services

(project-based services, which fulll customers' situation-driven needs).

In this paper we chose to focus on comparing rms that operate

with an installed-base (IB) or an input-to-process (I2P) business

logic. This choice was guided by three considerations. First, based on

an initial grouping of the case rms, we concluded that the empirical

material was over-represented in the rst two logics. As the samples

of rms were not originally collected in order to enable comparisons

across business logics, this over-representation may be a result of a

number of issues: industry structures in the countries covered, issues

related to the researchers' access to case rms, various rms' interest

levels in the issues discussed in the research processes (business

model innovation, solution sales, industrialization of solutions, and

growth through solution business), and the pre-dominance of these

business logics in an industrial manufacturing business-to-business

context. Second, as our aim was to illustrate differences between

709

industrial contexts, using the four identied continua as a lens, we

concluded that using the depth of data that we had accumulated for

the IB and I2P business logics was more important than a more shallow analysis of all the business logics. Finally, as we cross-checked our

data it seems reasonable to assume that the identied continua are

relevant also in other business logics, which highlights an important

avenue for further research.

For an overview of the generic characteristics of, and the differences

between the IB and I2P business logics, please refer to Appendix 1.

Building on these characteristics we were able to better compare and

contrast issues related to the development of solution business and

identify how the logics both support and impede the transformation

toward solution business models.

There are two major observations that arise from our research

with regards to differences in solution business models between IB

and I2P business logics respectively: IB rms can make a gradual transition toward solutions; whereas for I2P rms, the transformations are

less transitional and the rms need to address challenges connected to

taking major steps toward solutions. These observations are discussed

sequentially in Sections 4.1 and 4.2. The ndings are based on the synthesis from the extensive data collected as described above and are,

within each section, reported separately for each of the four identied

continua. Table 1 below summarizes some of the main points in the following discussion.

4.1. IB rms can make gradual transitions toward solutions

Firms operating with an IB logic provide investment goods and related

services, creating an installed base at the customers. IB businesses are

often characterized by project sales and many IB rms are faced with

long sale cycles. Additionally, the markets for investment goods such as

large-scale engines, paper mills, or IT systems are often truly global.

At present many IB rms experience competitive challenges related

to growing industry maturity and intensied competition, resulting in

slow growth and declining margins. On the other hand, information

technologies offer new opportunities in terms of remote monitoring

and control of equipment. Therefore, motivated by achieving higher

margins and continuous cash ows, many IB rms are taking steps toward solution business models and building after-sale activities based

on their installed base, aiming at exploiting product lifecycles.

The more advanced solution business models are often designed around

performance contracts, e.g. when the IB rm assumes responsibility for

Table 1

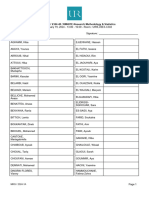

Overview of the solution business model transformation for IB and I2P rms.

Installed-base (IB)

Gradual transition toward solutions is possible

Input-to-process (I2P)

Transformation to solution business requires a major conscious step

Customer embeddedness

Increasing embeddedness by combining the capex

side's innate strategic importance at the customer

with the opex side's natural longitudinal cooperation.

Main way to increase embeddedness is to leverage technical

expertise and in-depth process understanding.

Offering integratedness

Various opportunities to increase integratedness

starting by adding opex services to capex projects,

and ending up in providing performance contracts

that integrate capex and opex businesses.

Two distinct alternatives to increase integratedness:

(1) optimizing the use of the

supplier's goods in the customer's process,

and (2) optimizing the customer's entire process.

Operational adaptiveness

Increasing adaptiveness through modular

offering structure in order to ensure repeatability

and to overcome organizational distance

of sales and production.

The asset heavy production and the need for economies

of scale limit the technically nearly limitless adaptation

possibilities; price increases used to make the

adaptiveness economically feasible for the provider.

Organizational networkedness

Internal organizational networkedness often increased

by setting up separate smaller solution units, external

organizational networkedness improved through

harmonized processes with the suppliers.

Internal organizational networkedness limited by regional

decentralized organizational structures, the level of required

external networkedness depends on chosen level of offering

integratedness (optimizing the use of supplier's goods requires

little close cooperation with other business partners, whereas

optimizing the customer's process may necessitate closer

business partnerships).

Author's personal copy

710

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

the performance of certain operations related to a customer's business

processes, and they are compensated based on system performance,

using metrics such as return on investment, process efciency, and

consistency.

Two different types of businesses characterize the activities within

IB rms: the capex business (capital expenditure, as when customers

invest in new plants, heavy machinery or information technology systems) and the opex business (operational expenditure, such as services,

maintenance and repair related to the capex investments done). Consequently, this division of capex and opex activities inuences the possibilities and opportunities for embeddedness, integratedness, adaptiveness,

and networkedness.

4.1.1. Customer embeddedness in customers' core vs. non-core processes

Many IB rms have (even before thinking about providing solutions)

established long term relationships with customers. An increased focus

on total cost of ownership and a lifecycle view of the equipment increase

the opportunities for higher embeddedness in the opex side of the business. However, the transition toward solutions changes the relationships with the existing customers from reactive services (focused on

repairs and maintenance) to more proactive service solution contracts

(focused on optimization of customers' processes).

Our research shows that most IB rms have, however, realized that

all customers are not interested in solutions. Despite the possibilities

to shift from reactive to proactive relationships, it does not necessarily

imply a shift in how strategic the relationship is viewed to be by the customer or even by the supplier itself. If the IB rm gets embedded in the

customers' core processes, then the rm is almost certainly viewed as a

strategic partner with access to high-level decision-makers of the

customer. On the other hand, if the rm increases its embeddedness in

customers' non-core processes, it is likely that the rm is not viewed as

a strategic solution provider. Additionally, it seems that embeddedness

in the opex business (non-core or core processes) does not necessarily

ensure solution business opportunities in the capex side of the business.

Consequently, a key issue for IB rms is to dene focus segments and

customers for the solution business, and develop segment and customer

specic value propositions.

According to our research, the capex offerings are often strategically important for the customers and therefore involve high-level

decision makers from different functions. Consequently, the capex

business is characterized by large separate transactions with limited

natural opportunities for longitudinal cooperation between the IB

rm and its customers. Thus, if the IB rm is seeking to initiate solution business from the capex side of the business, the embeddedness

has to be ensured with a comprehensive strategic account management program or similar. The goal of such program is to secure

long-term relationships and a move toward more continuous cash

ows, e.g., by introducing the opex side business to complement the

capex business, or to bundle capex and opex businesses into performance contracts.

4.1.2. Offering integratedness and the capex and opex conict

Our research identied two particularly interesting challenges related

to offering integratedness in IB rms: unbundleability and the integration

of capex and opex.

Whereas IB rms want to create integrated solutions, customers

have a tendency to want to unbundle them. The unbundleability of

the offering components varies in capex and opex sides of the IB business. Even though it is technically possible to unbundle the core capex

product, very few customers are interested in that, as this would require

them to acquire the needed assembly capabilities and resources. However, it is quite possible to unbundle many of the opex services. In

many cases other actors than the original equipment manufacturer

can perform the repair and maintenance services. The offerings become

better protected against customer-driven unbundling as the business

model moves toward performance contracts. In performance contracts

the customer usually signs an agreement with a single provider.

The integration of capex and opex businesses is not easy as both

sides have different starting points. The installed based created by

the capex projects is a natural place for the opex side to start providing

repair and maintenance services. As IB rms gain more experience, they

often expand their repair and maintenance services to also cover the

equipment manufactured by other actors. A long track record in

successful opex business, especially monitoring and control services,

creates a natural platform for entering solutions. These opex solutions

typically relate to running the existing capital equipment more efciently over their lifecycle, but do not necessary involve any new

capex components.

Selling fully-edged performance contracts, however, usually requires

a high level of integration between the capex and opex businesses. The

capex business has contacts to important powerful decision makers at

the customer side, whereas the opex side has long-term operational relationships. Together this embeddedness creates the platform for integrated solutions that can dramatically improve value creation both for the

customer and the supplier rm. Even though most rms realize this,

many rms tend to get stuck on the opex side. It seems that creating

the capex/opex integration is the key to successful transformation toward

a solution business model.

Among the investigated rms, those that do succeed in integrating

the capex and opex sides usually take deliberate strategic decisions to

move toward solutions. Rather than continuing the relatively natural

transition from repairs to maintenance toward performance contracts,

by just adding on different services, these rms invest in creating integrated solutions and enable capex sales to focus on selling solutions that

also cover the opex side.

4.1.3. Operational adaptiveness through modular congurations

Increasing operational adaptiveness poses considerable demands

for frictionless cooperation between the rm's sales, production, and

service operations. On the capex side of the IB businesses, the innate

adaptiveness to the customer situation varies considerably based on

the nature of the core product. In more simple installed base equipment

(e.g., elevators for low-rise residential buildings), the opportunities for

product tailoring are relatively low and the ability to customize the

offering based on customer needs is further lessened by the prevailing

product-oriented sales processes. On the other hand, in the case of

very complex and unique equipment (e.g., cruise liners), the product

is always tailored to meet the customer-specic needs from the very

beginning and the consultative sale processes associated with such

products are designed to support this consultative and adaptive

approach.

On the opex side of the IB business, the opportunities to adapt the

offering (i.e., repair, maintenance and process optimization) are in

theory almost limitless, but in reality optimal adaptiveness is not

reached because of the separation of capex and opex sale processes,

as well as the separated capex and opex purchasing processes of

customers; both separations seem to be very common in an IB context. This leads to a situation where the capex sale personnel may

have limited knowledge of the possibilities to adapt the rm's service

offering and the customer's need for adaptation.

As IB rms move toward solution business models and seek to

increase their adaptiveness in an economically feasible way, they

seem to adopt a modular offering structure and an information technology based offering conguration tools. These two aides help to

overcome the drift between the organizationally separate sales

and production: (1) by showing the sale persons the full range of

options available, and (2) by intentionally guiding the combination

of the modular options into solutions that simultaneously create

value for the customer as well as being technically and economically

feasible for the supplier.

Author's personal copy

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

711

4.1.4. Organizational networkedness and increased process

harmonization

In terms of organizational networkedness, the division into opex

and capex seems to create challenges for IB rms. In IB rms, capex

sales are usually geographically dispersed and separated from production, and sale personnel in IB rms do not often possess experience from the operational processes. Production and/or assembly

are relatively centralized, with a limited number of production and/

or assembly locations serving large geographical areas. The service

operations (e.g., repair and maintenance), on the other hand, are

typically organized locally, and many opex sale people have an operational background.

Many of the investigated IB rms operate within a business network

that is characterized by a multitude of reciprocal and relationally oriented

business relationships: the number of suppliers and other business

partners is high, and the objective is to create relatively long-term and

trusting relationships between the IB rm and its partners. Additionally,

it is not uncommon that process and offering harmonization reaches

levels in which the IB rm has integrated its enterprise resource planning

system with its suppliers' systems, enabling real-time optimization of the

entire business system. The relatively centralized organizational structure favored by many IB rms supports the creation of supplier management programs, which further support the level of networkedness

needed for solution business models.

Internally, the capex and opex separation affects the challenges

related to this continuum. For example, research and development

are usually focused on technical development of the capex side of

the business, with little knowledge about how to link technical opportunities to solution value propositions. As we have seen in the other

continua, the internal networkedness (integrating capex and opex

activities) becomes crucial if the rm is to deliver a solution. Many IB

rms therefore create smaller solution units in order to be able to

increase the internal networkedness and to experiment with different

types of solutions.

with long-standing contracts and regular contacts on the operational

level, the customer relationships tend to be strongly driven by price.

Therefore, there are some considerable challenges associated with increasing the embeddedness and becoming intimately involved in the

customers' core processes when designing solution business models.

First, the relationships are usually based on technical and operational

knowledge rather than knowledge about customers' business drivers.

Second, the I2P rms often produce goods that are used in customers'

non-core processes (e.g., magazine publishers consider content creation,

not printing the paper provided by the paper supplier, as their core process; electricity provided by a utility company is their only link to the

core processes of customers operating energy-intensive production).

Third, many I2P rms lack direct contact with the end customer since

their products are purchased and delivered to the end customer by a

specialized middle-man (e.g., paper merchants).

Despite these challenges, our research shows that opportunities

exist for I2P rms to increase customer embeddedness with selected

segments and customers. As many I2P rms' products are intrinsically

integrated into the customers' process (core or non-core), opportunities

exist to use their technical expertise and in-depth process understanding to create solutions improving the resource efciency of specic

customer processes. Additionally, many customers' lack of technical

and operational expertise related to their non-core processes open

opportunities to I2P rms for business process outsourcing solutions.

Similar to the IB rms, a well-functioning strategic account management program is usually a pre-requisite for increasing embeddedness.

However, whereas IB rms (especially on the capex side) use account

management to introduce long-term cooperation to their customer

relationships, the main objective of account management among I2P

rms is to gain access to the strategic decision-makers at the customer

and to generate more insight on customers' business drivers. Based on

this, decisions can be made whether to target customers' core and/or

non-core processes. This will in turn lead to an understanding of the

degrees of integratedness necessary for success.

4.2. Input-to-process rms need major steps toward solution business

4.2.2. Offering integratedness needs major steps

The unbundleability of the offering components does not seem to

be a major problem for the I2P rms. First, the core product of the I2P

rms (paper, chemical, electricity) is such that it is technically not

feasible to unbundle the product. The technical services related to

the use of the core product are also usually purchased from the producer

of the core product, as the relevance of the technical expertise is highly

dependent on the fact that the service personnel knows the composition

of the product in detail and has authority to discuss changes in the composition with the heads of the production. Similar to the IB performance

contracts, in process optimization or outsourcing, the customer is usually not that interested to unbundle the offering as it would work against

the overall value proposition of such a solution.

For the I2P rms, the process of integrating more components to

the solution seems less straightforward (and less transitional) than

for the IB rms. Essentially, the only way to differentiate commodities

is to look at the processes related to providing and using them. There

seems to be two approaches for I2P rms to help running their customers'

processes more effectively: (1) optimizing the use of the supplier's goods

in the customer's process, and (2) optimizing the customer's process. The

rst avenue is more common and is usually done by integrating service

elements to the overall offering (e.g., ensuring the right chemicals dosing

at the customer plant a practice that typically is called technical

service). There is, however, no natural transition from the rst type of

offering integratedness (i.e., optimizing the use of the good) to the second

(i.e., optimizing customer's process).

At the moment, there are relatively few examples of I2P rms taking

over customers' processes and many rms are hesitant to take such a

step. This hesitancy is most often explained by the following factors: (1)

the current low-margin business does not allow suppliers to take on the

risk exposures often associated with process outsourcing, (2) there is a

The I2P logic is relevant for rms providing goods that are utilized

as input in their customers' processes. The good is consumed or

transformed during the customer's process in such a way that it

ceases to exist as a separate entity and no installed base is created.

Producing goods such as steel, paper, or electricity requires major

investments into production facilities. Therefore, I2P rms often

have considerable assets in their balance sheets. Additionally, I2P

rms often have limited opportunities for offering differentiation,

leading to slim margins.

In order to tackle the challenges of asset-heavy production and

small margins, many I2P rms aim for strategies enabling them to

secure economies of scale and optimize their production capacity.

I2P rms tend to strive toward solution business models in which

their customers outsource their operations. An example of such solution business model can be found in the chemical business where

solution providers offer chemical management processes for customers, including inventory monitoring, re-ordering, and on-site distribution management. For I2P rms, the long-term contracts and the

input-to-production-process nature of their offering create almost

continuous cash ows from the current customers. Therefore, the

transition toward solution business among I2P rms is not so much

motivated by the need to transform discrete cash ows into continuous (as was the case for IB rms), but by the need to differentiate

from competition and to ensure sufcient margins.

4.2.1. Customer embeddedness: From arm's length to embedded

relationships

I2P rms have traditionally been suppliers of commodities. Even

though the I2P rms tend to have very long-term customer relationships

Author's personal copy

712

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

lack of suitable resources and capabilities to manage the customer's process with sufcient effectiveness (specically to integrate the expertise of

other suppliers), and (3) the limited contacts outside purchasing and

operations that often characterize I2P rms' customer relationships may

make the customers hesitant to make strategically important decisions

about outsourcing process management to the I2P rms.

4.2.3. Operational adaptiveness difcult due to asset heavy production

I2P rms often have asset heavy production facilities (e.g., paper

machine, renery, chemical plant, furnace, nuclear power plant, utility

infrastructure), which are designed to achieve economies of scale. The

good itself is standardized to enable long production runs, thus creating

inbuilt exibility challenges. Due to logistical challenges, production

facilities are usually organized on a regional basis. Technical service is

typically located in connection with customer plants/factories. Sales

tends to have stronger links to production than in IB rms; actually, it

is quite common to nd I2P rms in which the sale personnel report

directly to the production facility head and are responsible for lling

the facility's capacity.

In most cases, the core products of I2P rms offer technically limitless adaptation possibilities to the customer situations and processes:

paper can be produced in any thickness and width, and chemicals can

be manufactured in a multitude of concentration levels. However,

customizations are often deemed as economically unfeasible for the

provider. Therefore, the mindset of I2P sale personnel is more guided

by economies of scale thus challenging considerably the possibilities

to achieve high degrees of adaptiveness.

Due to the exible nature of their core products, I2P rms do not

usually seek to determine a modular offering structure when moving

toward a solution business model. Instead, the I2P rms tend to favor

creating guidelines that help the sale persons to increase adaptiveness

without compromising economies of scale. Pricing differentiation is

given a considerable emphasis in these guidelines: even though

some adaptations such as very special paper coating or 24/7 stock

availability are technically possible, they imply negative impacts on

the economies of scale which have to be covered by a price increase

for the customer.

4.2.4. Organizational networkedness restricted by regional structure

The business networks of many I2P rms are characterized by market driven business relationships. The number of suppliers and other

business partners may be high, but the relationships revolve mostly

around price and much of the raw materials are purchased through

auctions or other market mechanisms. The regional and relatively

de-centralized organizational structure makes it also fairly difcult

to establish rm-wide partnerships or partnership management

programs.

For I2P rms, the type of offering integratedness (optimize use of

goods vs. optimize process) affects the challenges associated with the

organizational networkedness. If the rms choose to optimize the

use of the supplier's goods in the customer's process, there is likely

to be less need for long-term and reciprocal relationships to other

suppliers i.e., external networkedness. However, if choosing to

optimize the customer's process there is likely to be a need for closer

business partnerships and external networkedness. For example, it is

not uncommon to see chemistry companies form strategic partnerships with dosing equipment manufacturers.

Internally, the de-centralized structure makes it difcult to create

and implement corporate wide solution initiatives, and achieve internal networkedness. In addition, because of the differences between

customers, it does not make sense to use trial and error, and

experiment with one customer (i.e., create separate units), since the

knowledge gained will most likely not be transferrable to other

customers.

5. Discussion

This paper responds to calls for providing specic guidelines and

tools for the development of solution business models in different

contexts (Baines et al., 2009), and for improving rms' capabilities to

co-create complex business solutions (Marketing Science Institute,

2010). In the paper we illustrate that using a business model lens contributes to our understanding of solution business in two interrelated

ways. First, by integrating a systemic and dynamic view on solution

business, it deconstructs the process denition of solutions, and conceptualizes changes taking place in four interrelated continua of specic relevance for industrial rms developing solution business

models. Second, using the continua, the paper identies opportunities and challenges related to developing solution business models

in two different industrial contexts: installed-base (IB) and

input-to-process (I2P). We will next describe these contributions

more closely.

5.1. Various degrees of change along four interdependent continua

To date there is not much research addressing the need for crossfunctional alignment (Nordin & Kowalkowski, 2010) in solution business model development. Previous research tends to focus on particular aspects of solution business. These aspects include servitization

(e.g., Baines et al., 2009; Mathieu, 2001), solution marketing and sales

(e.g., Anderson, Narus, & van Rossum, 2006; Spekman & Carraway,

2002; Tuli et al., 2007), solution strategy and management (e.g., Brady

et al., 2005; Davies, 2004; Galbraith, 2002a), and operation management related to product/service systems (e.g., Meier et al., 2010; Tan,

Matzen, McAloone, & Evans, 2010).

Our research incorporates all of these aspects and, thus, provides

an overview of the complexities associated with the transformation

toward solution business, as rms attempt to change the way that

they create value. The identied continua customer embeddedness,

offering integratedness, operational adaptiveness and organizational

networkedness emphasize degrees of change (rather than an absolute change) hereby facilitating the comparison of different types of

solution business models as well as challenges between and within

contexts.

The continua are interdependent, i.e., a change in one of them will

affect the others, and only a comprehensive view will help rms to

realize the value creation potential inherent in a transformation toward solution business. Consequently, there is a clear need for interaction between customer embeddedness and offering integratedness

in order to be able to develop customer specic value propositions. In

addition, degrees of integratedness and embeddedness need to be

balanced with various degrees of operational adaptiveness. This becomes especially important, as rms need to secure the delivery of

repeatable solutions. Various degrees of operational adaptiveness

imply different levels of offering component and process modularity,

which enables rms to cost-effectively match their solution with the

customers' processes, activities and characteristics. Furthermore, higher

degrees of offering integratedness and operational adaptiveness are

likely to demand higher degrees of organizational networkedness. It

becomes paramount to increase cooperation across functional as

well as organizational boundaries in order to increase integration of

components and achieve modularity. Higher levels of networkedness

imply a need for developing modular congurations across the

network.

5.2. Solution business models in two business logics

Extant literature on solution business gives few specic guidelines

and tools for developing solution business in different industrial contexts. Our research explicates that the nature and importance of, as

well as the interdependencies between, the identied continua differ

Author's personal copy

K. Storbacka et al. / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 705716

between industrial contexts. Consequently, also the challenges and

opportunities related to the transformation toward solution business

models will be different.

This is exemplied in the paper by analyzing the transformation

toward solution business models in two business logics (IB and I2P).

We found that IB rms can almost naturally transition toward solutions, usually by increasing the customer embeddedness and offering

integratedness and then addressing issues around the other continua.

Additionally, IB rms seem to have more opportunities to experiment

with different degrees on all continua, as well as different degrees of

dependencies between the continua. An IB rm can move from less

advanced service contracts, in which the interdependencies between

the continua are not necessarily that strong, toward increasingly

advanced interdependencies. In many cases, this gradual transition

actually prevents the rms from explicitly addressing the interdependencies and many rms end up with various kinds of mists between

the continua. For instance, rms may develop value propositions

related to customized life-cycle solutions, but end up not modularizing

the solutions and, hence, creating an operationally complex and untenable cost position.

For I2P rms, the changes needed are less transitional; rather

rms have to completely change their mental models and more

explicitly address the effects on all of the continua. Rather than gradually transitioning along the continua, I2P rms need to make choices

between possibly discrete options. There are especially strong overlaps

between offering integratedness, customer embeddedness and operational adaptiveness if the rm offers solutions related to optimizing the

use of the supplier's goods in the customer's process. In the optimizing

customer's process option, the overlaps are especially strong between

offering integratedness, customer embeddedness and organizational

networkedness. Many I2P rms seem to especially struggle with the

transformation toward fully-edged solutions, as this transformation

may mean that they have to change their business denition, for instance

by incorporating equipment and equipment maintenance into their solutions. The increased complexity resulting from such a move may increase

operational costs more than the solution business generates additional

revenue.

5.3. Further research avenues

The research process has several limitations that also constitute

potential avenues for further research. First, there are sampling biases

in the underlying studies, as these samples originally were not driven

by the comparison between IB and I2P, but rather by the case rms'

interest in, and experience from solution business. Hence, there are

more IB rms than I2P rms in the sample. Furthermore, it is clear

that the case-rms do not cover all possible forms of IB or I2P rms.

The IB sample is biased toward large scale investment goods, such

as machines and production lines. Component suppliers are clearly

underrepresented. The I2P sample is biased toward asset heavy production of commodities (electricity, chemicals, paper, etc.), which

may have overemphasized economies of a scale. I2P rms focusing

on highly specialized goods and operating a batch production system may experience different challenges. Consequently, sampling

should be developed in order to cover a larger array of both IB and

I2P rms and more research is needed specically focusing on I2P

rms.

Second, there are other business logics that would warrant further

investigation. Nenonen and Storbacka (2010) identify three additional

generic business logics in business-to-business rms: continuous relationships (services that are characterized by long-term contracts);

consumer-brands (products for the consumer market that are sold

through a channel); and situational services (project-based services,

which fulll customers' situation-driven needs). A further exploration

of the differences between solution business models in these business

713

logics would improve our understanding of the transformation toward

solution business.

Third, some of the solution business model dimensions are less

investigated than others within the solution literature. Issues that

would need additional investigation are for instance: how do rms

select segments and/or customers that they focus their solution

business models on, what are the challenges related to targeting

customers' core versus non-core processes, and how do the customers' capabilities inuence successful solution business model

development?

Finally, the research suggests a need to apply a network perspective in developing solution business models. This highlights role

of the network actors in co-creating the solution. The idea of value

co-creation in a network includes the idea of reciprocity, i.e., not

only should one be freed from a dyadic perspective, but also from

the providercustomer notion. Adapting an actor-to-actor perspective (Vargo & Lusch, 2011) would emphasize the role of the customer in developing solution business models. It is clear that customers

buying solutions also need to adapt their business models, and

this perspective constitutes an interesting avenue for further

research.

5.4. Managerial implications

The research highlights several important implications for rms

wanting to develop their solution business. It suggests that moving

toward solution business requires changes in all parts of the business

model. Hence, rms should be liberated from the shackles of functional thinking, and that they need to make solution business

development a common strategic priority anchored within top

management. Without managerial commitment, the need for resources for developing new capabilities may not be recognized

within functions that are not customer facing. By making the solution business a priority for the whole rm, all functions can more

easily be aligned.

It is important to note the interdependence of the identied continua. Moving toward greater embeddedness will, for instance, require changes also in the other continua. Furthermore, having an

excellence only in one of the business dimensions may not create a

sufcient competitive advantage, if the rm has capability gaps in

the other dimensions. The key is to secure congurational t between

the dimensions and develop gradually and simultaneously across

dimensions.

This paper does not suggest that there is one ideal solution business model for any particular business logic. Instead, it argues that

there are several possible solution business models that may be

equally successful. The comparison between the IB and I2P business

logic, however, clearly highlights that rms need to be careful when

benchmarking across industrial contexts. A setup that works and creates value in one industry may not be viable in another industry, due

to the underlying logic of that industry. It is, hence, important to understand the underlying business logic and implement changes based

on this. This will also make it easier to identify where problems will

arise.

When analyzing the participating case-rms, we noted that there

are major differences in how rms have started their solution business. Due to the natural extension into life-cycle thinking, many of

the IB rms have more or less drifted toward solution business, letting opportunities identied among customers drive a quest toward

solutions. Other rms, particularly those with an I2P business logic,

start with strategic decisions and make deliberate investments in

building the necessary capabilities on a broad scale. The research

does not provide us with evidence on which development path is

more effective, but it clearly indicates that a gradual development is

particularly difcult for rms in the I2P context.

Author's personal copy

714

Appendix 1. Characteristics of installed-base (IB) and input-to-process (I2P) business logics

Customer

Product market characteristics

Geographical market

characteristics

Main competitive drivers

Importance of the good to

the customer

Sale case characteristics

Customer relationship

characteristics

Offering

Capex goods are typically sold as distinct sale cases that can be followed in a sale funnel.

Efforts to win the most desired sale cases

In capex business the intensity of the customer relationships varies from

intense cooperation (during the sale case) to little/no cooperation

(between the sale cases), usually contacts in various functions incl. top management

Capex business usually very cyclical (dependent on customers' propensity

to make investments), opex business usually resistant to economic cycles

Detect and win the best sale cases (capex) and maximize the service coverage in the

available installed base (opex)

Characteristics of the

core product

Possibilities to differentiate the core product (capex) vary from moderate to almost limitless;

capex products create an installed base at the customer that requires life-cycle services

Earning uctuation

from the core product

Typical value

proposition elements

Offering structure

Project-based cash ows from the capex products, no cash ows after the project has

been delivered

Use value of the products (what does the product enable), cost efciency over the product

life-cycle, product quality

The capex product usually consists of many product categories and versions within a

category, usually a wide range of opex services with varying levels of standardization

Role of services

To provide more stable and continuous cash ows, to provide continuous contacts

to the customer; services are often prices separately from the products

Traditionally cost-plus and market pricing, trend toward value-based pricing

Possibilities to differentiate the core product vary from none to very

moderate; core product vanishes/changes in the customer

processes no installed base requiring life-cycle services

Continuous cash ows from the core product, e.g., monthly payments

based on contracts

Competitive price, possibilities to improve customers' process

efciency, product quality

The core product can often be customized based on customer needs

in certain variables (e.g., paper thickness, width; chemicals

concentration), services typically technical services with limited levels

of standardization

To differentiate from the competition and to ensure sufcient

margins; services do not usually carry a separate price from the product

Market pricing or marginal pricing

Characteristics of core

product production

Investments into

production facilities

Capex production typically divided into component manufacturing and assembly

Integrated production facilities due to process or batch production

Investments into production facilities vary from moderate to considerable

Centralization of production

Manufacturing and assembly of capex product centralized in order to achieve economies of scale

Business network &

supply chain

Often a very considerable supplier network supplying components and sub-modules;

many capex good providers focus on assembly and manufacture only some critical

components/modules

Just-in-time deliveries very important to the customers (e.g., delivering the escalator

when optimal for the construction project)

Services are produced locally, usually country or area specic service teams

Often very asset heavy production facilities requiring considerable

investments (e.g., paper machine, oil renery, chemical plant, furnace,

nuclear power plant, utility infrastructure)