Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

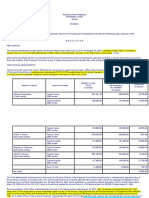

Rule 39-B

Загружено:

Francis Emmanuel ArceoАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Rule 39-B

Загружено:

Francis Emmanuel ArceoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

G.R. No.

L-49576

November 21, 1991

JOSEFINA B. CENAS and THE PROVINCIAL SHERIFF OF

RIZAL, petitioners,

vs.

SPS. ANTONIO P. SANTOS and DRA. ROSARIO M.

SANTOS and HON. PEDRO C. NAVARRO, Presiding

Judge, CFI-Rizal, Br. III, respondents.

Facts:

This is a petition for review on certiotari seeking

to annual and set aside the August 28, 1978

decision ** of the then Court of First Instance of

Rizal in Civil Case No. 20435 enjoining the

Provincial Sheriff of Rizal and any other person

in his behalf from proceeding with the auction

sale predicted upon the petition for extrajudicial foreclosure prayed for by petitioner

Josefina B. Cenas; and the December 4, 1978

Order of the same court denying the motion for

reconsideration.

On May 3, 1976, the spouses Jose Pulido and

Iluminada M. Pulido mortgaged to Pasay City

Savings and Loan Association, Inc. their land

covered by TCT No. 471634, subject of this case,

to secure a loan of P10,000.00. The said

mortgage was registered with the Registry of

Deeds on the same date and was duly

annotated in the title of the property.

On May 18, 1976, the said mortgaged land was

levied upon by the City Sheriff of Quezon City

pursuant to a writ of execution issued by the

then Court of First Instance of Quezon City in

Civil Case No. Q-2029 entitled, "Milagros C.

Punzalan vs. Iluminada Manuel-Pulido"; and

eventually, on July 19, 1976, the same was sold

to herein petitioner Josefina B. Cenas who was

the highest bidder in the execution sale.

On January 18, 1977, Pasay City Savings and

Loan Association, Inc. assigned to petitioner

Cenas all its rights, interests, and participation

to the said mortgage, for the sum of P8,110.00,

representing the unpaid principal obligation of

the Pulidos as of October 6, 1976, including

interest due and legal expenses. Thus,

petitioner became the purchaser at the public

auction sale of the subject property as well as

the assignee of the mortgage constituted

thereon.

On July 19, 1977, herein private respondent Dra.

Rosario M. Santos redeemed the said property,

paying the total sum of P15,718.00, and was

accordingly issued by the City Sheriff of Quezon

City a Certificate of Redemption.

On April 17, 1977, petitioner Cenas, as the

assignee of the mortgage loan of the Pulidos

which remained unpaid, filed with the Office of

the Provincial Sheriff of Rizal, a verified petition

for extra-judicial foreclosure of the mortgage

constituted

over

the

subject

property.

Accordingly, the subject property was advertised

for sale at public auction on May 15, 1978.

On the other hand, private respondents,

spouses Antonio P. Santos and Dra. Rosario M.

Santos, apprised of the impending auction sale

of the said property, filed an affidavit of adverse

claim with the Provincial Sheriff of Rizal,

claiming that they had become the absolute

owners of the property by virtue of Certificate of

Redemption, dated July 20, 1977, issued by the

City Sheriff of Quezon City; and on May 11,

1978, filed with the respondent court a verified

Petition

for

Prohibition

with

Preliminary

Injunction to enjoin the Provincial Sheriff of Rizal

from proceeding with the public auction sale of

the property in question. To this petition,

petitioners filed their Answer on May 18, 1978.

Private respondents filed a Motion to Amend

Petition together with the Amended Petition,

which was opposed by the petitioners. The trial

court, in its Order of July 17, 1978, denied the

motion and ordered the parties to submit

simultaneous memoranda.

After the parties have submitted their respective

memoranda, the trial court rendered its

judgment dated August 28, 1978 in favor of

private respondents, the dispositive portion of

which reads:

WHEREFORE,

premises

considered,

the

respondent Provincial Sheriff of Rizal and any

other persons acting in his behalf are hereby

enjoined from proceeding with the auction sale

predicated upon the petition for extra-judicial

foreclosure prayed for by respondent Josefina B.

Cenas.

The trial court held that the redemption of the

subject property effected by the herein private

respondents, "wipe out and extinguished the

mortgage executed by the Pulido spouses favor

of the Pasay City Savings and Loan Association,

Inc."

Issue:

WON the redemption of the questioned property

by herein private respondents wiped out and

extinguished the pre-existing mortgage obligation of

the judgment debtor, Iluminada M. Pulido for the

security of which (mortgage debt) the subject property

had been encumbered?

Held:

NO!

Ratio:

Section 30, Rule 39 of the Rules of Court,

provides for the time, manner and the amount to be

paid to redeem a sold by virtue of a writ of execution.

Pertinent portion reads:

Sec. 30.

Time and manner of, and amounts

payable on, successive redemptions. Notice to be

given and filed. The judgment debtor, or

redemptioner, may redeem the property from the

purchaser, at any time within twelve (12) months after

the sale, on paying the purchaser the amount of his

purchase, with one per centum per month interest

thereon in addition, up to the time of redemption,

together with the amount of any assessments or taxes

which the purchaser may have paid thereon after

purchase, and interest on such last-named amount at

the same rate; and if the purchaser be also a creditor

having a prior lien to that of the redemptioner, other

than the judgment under which such purchase was

made, the amount of such other lien, with

interest. . . . . (Emphasis supplied)

Under the above-quoted provision, if the purchaser is

also a creditor having a prior lien to that of the

redemptioner, other than the judgment under which

such purchase was made, the redemptioner has to

pay, in addition to the prescribed amounts, such other

prior lien of the creditor-purchaser with interest.

In the instant case, it will be recalled that on May

3,1976, the Pulidos mortgaged the subject property to

Pasay City Savings and Loan Association, Inc. who, in

turn, on January 8, 1977, assigned the same to

petitioner Cenas. Meanwhile, on July 19, 1976,

pursuant to the writ of execution issued in Civil Case

No. Q-2029 (Petitioner Cenas is not a party in this case

No. Q-2029), the subject property was sold to

petitioner Cenas, being the highest bidder in the

execution sale. On July 19, 1977, private respondent

Dra. Rosario M. Santos redeemed the subject property.

Therefore, there is no question that petitioner Cenas

as assignee of the mortgage constituted over the

subject property, is also a creditor having a prior

(mortgage) lien to that of Dra. Rosario M. Santos.

Accordingly, the acceptance of the redemption amount

by petitioner Cenas, without demanding payment of

her prior lien the mortgage obligation of the Pulidos

cannot wipe out and extinguish said mortgage

obligation. The mortgage directly and immediately

subjects the property upon which it is imposed,

whoever the possessor may be, to the fulfillment of

the obligation for whose security it was constituted

(Art. 2126, Civil Code). Otherwise stated, a mortgage

creates a real right which is enforceable against the

whole world. Hence, even if the mortgaged property is

sold (Art. 2128) or its possession transferred to

another (Art. 2129), the property remains subject to

the fulfillment of the obligation for whose security it

was constituted (Padilla, Civil Code annotated, Vol. VII,

p. 207, 1975 ed.).

It will be noted that Rule 39 of the Rules of Court is

silent as to the effect of the acceptance by the

purchaser, who is also a creditor, having a prior lien to

that of the redemptioner, of the redemption amount,

without demanding payment of her prior lien. Neither

does it provide whether or not the redemption of the

property sold in execution sale freed the redeemed

property from prior liens. However, where the prior lien

consists of a mortgage constituted on the property

redeemed, as in the case at bar, such redemption does

not extinguish the mortgage (Art. 2126). Furthermore,

a mortgage previously registered, like in the instant

case, cannot be prejudiced by any subsequent lien or

encumbrance annotated at the back of the certificate

of title (Gonzales v. Intermediate Appellate Court, 157

SCRA 587 [1988]).

Moreover, it must be stressed that private respondents

redeemed the property in question as "successor in

interest" of the judgment debtor, and as such are

deemed subrogated to the rights and obligations of the

judgment debtor and are bound by exactly the same

condition relative to the redemption of the subject

property that bound the latter as debtor and

mortgagor (Sy vs. Court of Appeals, 172 SCRA 125

[1989]; citing the case of Gorospe vs. Santos, G.R. No.

L-30079, January 30, 1976, 69 SCRA 191). Private

respondents, by stepping in the judgment debtor's

shoes, had the obligation to pay the mortgage debt,

otherwise, the debt would and could be enforced

against the property mortgaged (Tambunting vs.

Rehabilitation Finance Corporation, 176 SCRA 493

[1989]).

THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS and MARINDUQUE

MINING AND INDUSTRIAL CORPORATION, respondents.

G.R. No. 84526

January 28, 1991

PHILIPPINE COMMERCIAL & INDUSTRIAL BANK and JOSE

HENARES, petitioners,

vs.

Facts:

A group of laborers obtained a favorable

judgment against the Marinduque Mining and

Industrial Corporation for the payment of

backwages amounting to P205,853 before the

National Labor Relations Commission. A writ of

execution was issued and the Deputy Sheriff

served the writ, but it was unsatisfied. The

sheriff prepared on his own a Notice of

Garnishment addressed to six banks in Bacolod

City, including petitioner PCIB, directing the

bank concerned to issue a check in satisfaction

of the judgment.

While the in house lawyer of the Corporation

warned the PCIB to withhold any release of its

deposit with the bank, the bank issued a

managers check in the amount of P37,466

which was the exact balance of the private

respondents account as of that day. The said

check was also encashed by the sheriff the next

day.

Marinduque Mining thus filed a complaint before

the RTC of Manila against PCIB and the deputy

sheriff, alleging that its current deposit with the

petitioner bank was levied upon, garnished, and

with undue haste unlawfully allowed to be

withdrawn, and notwithstanding the alleged

unauthorized disclosure of the said current

deposit and unlawful release thereof, the latter

have failed and refused to restore the amount of

P37,466 to the formers account despite

repeated demands.

Trial court rendered judgment in favor of

Marinduque Mining Corporation. On appeal, the

Court of Appeals initially reversed the trial

courts order but later affirmed it. Thus, this

petition to the SC.

Issue:

WON the petitioners violated RA 1405,

otherwise known as the Secrecy of Bank Deposits

Act, when they allowed the sheriff to garnish the

deposit of Marinduque Mining Corporation?

Held:

NO!

Ratio:

The SC first ruled that the release of the deposit

by the bank was not done in undue and indecent

haste. We find the immediate release of the funds

by the petitioner bank on the strength of the notice

of garnishment and writ of execution, whose

issuance, absent any patent defect, enjoys the

presumption of regularity.

The SC likewise did not find any violation

whatsoever by the petitioners of RA 1405,

otherwise known as the Secrecy of Bank Deposits

Act. The Court, in China Banking Corporation v.

Ortega, had the occasion to dispose of this issue

when it stated, to wit:

It is clear from the discussion of the conference

committee report on Senate Bill No. 351 and House

Bill No. 3977, which later became Republic Act No.

1405, that the prohibition against examination of or

inquiry into a bank deposit under Republic Act No.

1405 does not preclude its being garnished to

insure satisfaction of a judgment. Indeed, there is

no real inquiry in such a case, and if existence of

the deposit is disclosed, the disclosure is purely

incidental to the execution process. It is hard to

conceive that it was ever within the intention of

Congress to enable debtors to evade payment of

their just debts, even if ordered by the Court,

through the expedient of converting their assets

into cash and depositing the same in a bank.

Since there is no evidence that the petitioners

themselves divulged the information that the

private respondent had an account with the

petitioner bank and it is undisputed that the said

account was properly the object of the notice of

garnishment and writ of execution carried out by

the deputy sheriff, a duly authorized officer of the

court, we cannot therefore hold the petitioners

liable under RA 1405.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Mustang Lumber vs. CA GR No. 104988, June 18, 1996Документ22 страницыMustang Lumber vs. CA GR No. 104988, June 18, 1996bingkydoodle1012Оценок пока нет

- Re Coa FTДокумент7 страницRe Coa FTLoisse VitugОценок пока нет

- Golden Ribbon Lumber Vs City of ButuanДокумент3 страницыGolden Ribbon Lumber Vs City of ButuanFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Rule 39 Partial ArrangedДокумент66 страницRule 39 Partial ArrangedFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Mustang Lumber vs. CA GR No. 104988, June 18, 1996Документ22 страницыMustang Lumber vs. CA GR No. 104988, June 18, 1996bingkydoodle1012Оценок пока нет

- Consing Vs Court of AppealsДокумент7 страницConsing Vs Court of AppealsFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Arceo Rule 39Документ10 страницArceo Rule 39Francis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- 1 Civil Procedure - Nature of Action of PartitionДокумент8 страниц1 Civil Procedure - Nature of Action of PartitionFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Bayer V Agana 1975Документ4 страницыBayer V Agana 1975Karen PascalОценок пока нет

- Ornamental PlantsДокумент6 страницOrnamental PlantsFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Arceo - Evidence Rule 130Документ9 страницArceo - Evidence Rule 130Francis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- For PrintingДокумент1 страницаFor PrintingFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Arceo Rule 39Документ10 страницArceo Rule 39Francis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- List of Cases in Labor RelationsДокумент1 страницаList of Cases in Labor RelationsFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Civil CodeДокумент11 страницCivil CodeFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Ornamental PlantsДокумент6 страницOrnamental PlantsFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Office Receiving Sheet For PleadingsДокумент2 страницыOffice Receiving Sheet For PleadingsFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Office Receiving Sheet For PleadingsДокумент2 страницыOffice Receiving Sheet For PleadingsFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Teague Vs Fernandez To Philam Insurance Company, Inc Vs CAДокумент13 страницTeague Vs Fernandez To Philam Insurance Company, Inc Vs CAFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Notarial Report BlankДокумент1 страницаNotarial Report BlankFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Del San Transport Lines Case To DM ConsunjiДокумент12 страницDel San Transport Lines Case To DM ConsunjiFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Digest 2 - Tua Vs MangrobangДокумент4 страницыDigest 2 - Tua Vs MangrobangFrancis Emmanuel Arceo67% (3)

- Treasurer's AffidavitДокумент1 страницаTreasurer's AffidavitFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Corpo Teves Gamboa NickelДокумент9 страницCorpo Teves Gamboa NickelFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Li Vs Sps SolimanДокумент2 страницыLi Vs Sps SolimanFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Cruz Vs DenrДокумент3 страницыCruz Vs DenrFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Far Eastern Export & Import Co. v. Lim Teck SuanДокумент2 страницыFar Eastern Export & Import Co. v. Lim Teck SuanFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Torts Dulay Vs CAДокумент9 страницTorts Dulay Vs CAFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- 3 Valenzuela Vs CAДокумент4 страницы3 Valenzuela Vs CAFrancis Emmanuel ArceoОценок пока нет

- Character Traits and Black Beauty PageДокумент1 страницаCharacter Traits and Black Beauty PageROSE ZEYDELISОценок пока нет

- Crime FictionДокумент19 страницCrime FictionsanazhОценок пока нет

- Human Rights in Pakistan 22112021 115809am 1 03112022 115742amДокумент6 страницHuman Rights in Pakistan 22112021 115809am 1 03112022 115742amaiman sattiОценок пока нет

- Prubankers Association Vs Prudential BankДокумент2 страницыPrubankers Association Vs Prudential BankGillian Caye Geniza Briones0% (1)

- Pook SAM Guide v4.0Документ59 страницPook SAM Guide v4.0DwikiSuryaОценок пока нет

- Religion Between Violence and Reconciliation PDFДокумент605 страницReligion Between Violence and Reconciliation PDFAnonymous k1NWqSDQiОценок пока нет

- List of Argument Essay TopicsДокумент4 страницыList of Argument Essay TopicsYoussef LabihiОценок пока нет

- Application For Compensatory Time Day-OffДокумент1 страницаApplication For Compensatory Time Day-Offjerick16Оценок пока нет

- Abubakar Ibrahim Name: Abubakar Ibrahim Adm. No 172291067 Course Code: 122 Course Title: Citizenship Education Assignment: 002Документ3 страницыAbubakar Ibrahim Name: Abubakar Ibrahim Adm. No 172291067 Course Code: 122 Course Title: Citizenship Education Assignment: 002SMART ROBITOОценок пока нет

- In The Matter of Blanche O'Neal v. City of New York, Et Al.Документ51 страницаIn The Matter of Blanche O'Neal v. City of New York, Et Al.Eric SandersОценок пока нет

- Facts:: G.R. No. 70615 October 28, 1986Документ6 страницFacts:: G.R. No. 70615 October 28, 1986Mikes FloresОценок пока нет

- Professional DisclosureДокумент4 страницыProfessional Disclosureapi-354945638Оценок пока нет

- CSC 10 - MOCK EXAM 2022 WWW - Teachpinas.com-35-47Документ13 страницCSC 10 - MOCK EXAM 2022 WWW - Teachpinas.com-35-47mnakulkrishnaОценок пока нет

- LIMITATION ACT ProjectДокумент22 страницыLIMITATION ACT ProjectHARSH KUMARОценок пока нет

- Ancient Warfare 2021-11-12Документ60 страницAncient Warfare 2021-11-12BigBoo100% (6)

- 2011 Basil PantelisДокумент3 страницы2011 Basil PanteliselgrecosОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Bailout Funding - 19012008Документ14 страницAnalysis of Bailout Funding - 19012008ep heidner100% (6)

- Gender, Religion and CasteДокумент5 страницGender, Religion and CastePRASHANT SHARMAОценок пока нет

- Comments On Supremacy of European UnionДокумент6 страницComments On Supremacy of European UnionNabilBariОценок пока нет

- Getting Older: Billie EilishДокумент1 страницаGetting Older: Billie EilishDummy GoogleОценок пока нет

- CLJIP FinalДокумент21 страницаCLJIP FinalGretchen Curameng100% (3)

- Obc CirtificateДокумент1 страницаObc Cirtificatejnaneswar_125467707Оценок пока нет

- PB 06-63 Denial of Ssns For Non CitizensДокумент4 страницыPB 06-63 Denial of Ssns For Non CitizensJeremiah AshОценок пока нет

- 15 4473 RTJДокумент6 страниц15 4473 RTJEd MoralesОценок пока нет

- 1:13-cv-01861 #115.attachments Part 2Документ331 страница1:13-cv-01861 #115.attachments Part 2Equality Case FilesОценок пока нет

- အသစ္ျပဳျပင္ျပဌာန္းထားေသာ ဂ်ပန္ လူ၀င္မႈႀကီးၾကပ္ေရး ဥပေဒДокумент18 страницအသစ္ျပဳျပင္ျပဌာန္းထားေသာ ဂ်ပန္ လူ၀င္မႈႀကီးၾကပ္ေရး ဥပေဒMai Kyaw OoОценок пока нет

- MIL PeTaДокумент2 страницыMIL PeTaAaron James AbutarОценок пока нет

- Rad BrochureДокумент2 страницыRad Brochureapi-360330020Оценок пока нет

- 2022.03.01 - OSH AmendmentsДокумент98 страниц2022.03.01 - OSH AmendmentsEZATI HANANI MURDIОценок пока нет

- Diffie Hellman AlgorithmДокумент11 страницDiffie Hellman Algorithmjoxy johnОценок пока нет