Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Visual Analysis: Nam June Paik's Electronic Superhighway

Загружено:

gabrielleАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Visual Analysis: Nam June Paik's Electronic Superhighway

Загружено:

gabrielleАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Gabrielle Fernandez

Visual Analysis

Twenty-First Century Route 66

Sixty-three-year-old, Nam June Paik, balanced from twenty-foot scaffolding to configure the

three hundred sixty-six televisions and six hundred feet of neon it took to frame his largest statement

(Paik). Electronic Super Highway: Continental U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii is a visual metaphor that uses

movement, rhythm and lines to show how the media can shape one mans shallow perception of a diverse

nation.

Paik immigrated to the U.S. from South Korea when he was thirty-two years old. In New York

City, he was swept into the artist coterie of the Neo-Dada era and emerged as the father of video art

(Hanhardt). Like other artists from this group, Paik formed his creations through the use of mass media

and found objects. He viewed the television screen as his canvas and he believed that its versatility would

allow him to shape his art as precisely as Leonardo and as freely as Picasso (Hanhardt). With an array

of abandoned TVs and electric components, he manifested his mental images into an Electronic

Superhighway, a term he originally coined in a 1974 proposal (Media Planning for the Postindustrial

Society). Paiks futuristic mindset moved him to integrate modern technology and art during a time

when visual media had begun to be a central presence within American homes. Electronic Super

Gabrielle Fernandez

Visual Analysis

Highway: Continental U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii, 1995, emulates the effect that this informative presence

has on the viewers awareness.

Permanently on display in the Lincoln Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the

massive United States stretches forty-feet long and towers over spectators at fifteen feet. Each state is

bordered by bright pulsing neon and filled with an assortment of TVs. The segmented TVs are connected

to fifty different DVD players that simultaneously loop visual and audio reels, as a representation of

contrasting state identity. The screens, in union with the neon, illuminate the dimly lit gallery with a

wattage as memorable as Times Square. At first glance, the piece appears to be of mammoth proportions

because it offers viewers a brimming platter of American culture to absorb. The bolting movement might

overtake the viewers sight as their eyes strain to hold glimpses of recognizable footage, but connotations

will arise from the chaos. In Kansas, scenes from the The Wizard of Oz can be recognized, and in

Oklahoma, Roger and Hammersteins Oklahoma! (Broun). These classic films, along with Missouris

Meet Me in St. Louis, are the only clips in the piece that were not created by Paik himself (Broun). Some

states contain a blinking set of images, as your mind might call on multiple symbols when a state is

mentioned in conversation or by the media. For insistence, Texas features a cactus, a cowgirl, and a clip

from the Branch Davidian burning (Broun). These images are looping with a high rate of change which

can make the symbolism difficult to identify. Observers might feel compelled to zone in on each state

individually to order to decipher the fleeting messages.

An important idea to keep in mind when analyzing this piece is that Paik chose his film based on

his media-based impression of each state. The images the artist chose to feature is not a depiction of his

only knowledge of the regions, as it would be less effective to display his every thought and experience

tied to each state. Across the piece, Paik maintains focus on the perception the media paints, not only for

naturalized Americans but for anyone exposed to American culture. Electronic Super Highway:

Continental U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii is a rhythmic portrait that streams only the artists initial thoughts, a

stereotypical visual manifested by the media. The sound flowing from the piece is as impactful as the

radiating light and color. The film clips are accompanied by full audio which is released into the gallery

to create a layer of sound fifty levels deep. At first, the audio is a blurred cadence of singing, clanking,

music, and static. From the capering wavelengths rings the bellowing voice of Dr. Martin Luther King,

who can be found inside the black and white televisions within Alabama. The audio element enhances

the symbolism for this piece, especially when a voice or song is as recognizable as the referenced image.

Across the country in California, notions of rising technological development are represented by the

raining pings of passing zeroes and ones. The pings shift into an upbeat tune as O.J. Simpson appears on

the screens casted as the leader of a workout class filled with blonde, tanned women. Even though this

Gabrielle Fernandez

Visual Analysis

particular mashup is collectively humorous, serious undertones can be caught from the idea that O.J.

Simpson was in fact an accused murderer whose case turned into daytime entertainment for many people.

Paiks use of audio helped him to achieve mixed moods of sorrow, nostalgia, and humor by uniting

diverse visuals and tracks to create one, powerful rhythm.

Once the viewer is able to peel through the audio and video layers of this piece, they are left with

flickering neon lines. Paik uses lines to distinguish the areas from one another both culturally and

geographically. Before television achieved its strong presence throughout American homes, the typical

way to experience a states culture was to load up the family vehicle and hit the highway. As hinted by

the title, the media has created an Electric Superhighway that has allowed people to gather knowledge and

experiences from variety of places without vacating the comfort of their home. The catch of this

convenience is that information solely gathered though this medium will produce only a partial or shallow

understanding of a place or subject. Adding further meaning to the use of lines, the artist chose to place a

triple layer of neon tubing alongside the Mississippi River. The river acts as a strong border between

states at the threshold to the West from the East. This emphasis is tied to the deeper meaning of the piece

because traditionally the United States is thought to be divided into northern and southern entities. By

highlighting the directional shift in the divide, Paik alludes to progression towards future. The west has

always been a symbol of development for the United States, growing from the countries early focus on

Manifest Destiny. This piece directly broadcasts the achievements and advancements that have been

made past the Mississippi River. The motivation behind forward thinking can be linked to increasing

information accessibility, which has been aided by the recorded documentation produced by the media.

A South Korean immigrant, aged sixty-three years, wrestled with thirty-seven hundred feet of

cable and six hundred feet of neon, to colossally expose the shallow effect the media has on its viewers

perceptions (Paik). Nam June Paik expressed his ideas through the use of bustling movement,

disorganized rhythm, and boundary lines. In Electronic Super Highway: Continental U.S., Alaska, and

Hawaii, the art cannot be found within the film housed by the televisions, but rather in the collective

movement and rhythm linked together as one chaotic display of diversity.

Gabrielle Fernandez

Visual Analysis

Works Cited

Broun, Betsy. "Exploring the Electronic Superhighway." Interview by Lynn Neary. National Public

Radio. National Public Radio, 4 July 2006. Web. 19 March 2016.

Hanhardt, John G. Nam June Paik. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in Association with

W.W. Norton, 1982. Print.

Paik, Nam June. Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii. 1995. Smithsonian

American Art Museum. American Art. Web. 19 March 2016.

---. "Media Planning for the Postindustrial Society The 21st Century Is Now Only 26 Years Away."

Media Art Net. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 March 2016.

Вам также может понравиться

- The New Simandl PreviewДокумент20 страницThe New Simandl Previewrichard arratia100% (2)

- Nirvanas in Utero PDFДокумент112 страницNirvanas in Utero PDFtululotres100% (3)

- Signs of Subversion at Cultural CrossroadsДокумент5 страницSigns of Subversion at Cultural CrossroadsFernando García100% (1)

- Spring 2013 Interweave Retail CatalogДокумент122 страницыSpring 2013 Interweave Retail CatalogInterweave100% (2)

- Drill Grinder Instructions 0CECFEC7086BDДокумент8 страницDrill Grinder Instructions 0CECFEC7086BDMIGUEL ANGEL GARCIA BARAJASОценок пока нет

- Lucy Lippard - Max Ernst: Passed and Pressing TensionsДокумент7 страницLucy Lippard - Max Ernst: Passed and Pressing TensionsMar DerquiОценок пока нет

- Alfred'S Basic Guitar Method: Opies SoДокумент4 страницыAlfred'S Basic Guitar Method: Opies SoAlex LuisОценок пока нет

- Nam June Paik EssayДокумент29 страницNam June Paik EssayMarie-Christine Camus100% (2)

- Ten Key Texts On Digital ArtДокумент10 страницTen Key Texts On Digital ArtChris RenОценок пока нет

- Pop Art - Group 9Документ20 страницPop Art - Group 9Rechelle RamosОценок пока нет

- Pop ArtДокумент23 страницыPop ArtSian QuincoОценок пока нет

- The Invention of FormsДокумент31 страницаThe Invention of FormsEric MosesОценок пока нет

- Conceptual ArtДокумент14 страницConceptual ArtLuduvina Perlora100% (1)

- Oliver Marchart, Art, Space and The Public SphereДокумент19 страницOliver Marchart, Art, Space and The Public SphereThiago FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Sample Essay - Jackson PollockДокумент2 страницыSample Essay - Jackson Pollockapi-211813321100% (1)

- Christiane Paul Context and ArchiveДокумент20 страницChristiane Paul Context and ArchivecybercockОценок пока нет

- Locating The Producers' Durational Approaches To Public ArtДокумент221 страницаLocating The Producers' Durational Approaches To Public ArtRifki APОценок пока нет

- Public Art, Private PlacesДокумент20 страницPublic Art, Private PlacesLisa Temple-CoxОценок пока нет

- Berklee Brush Patterns For DrumsДокумент12 страницBerklee Brush Patterns For DrumsReinaldo Tobon0% (2)

- 1969 - Earth Art Exhibition - CatalogueДокумент92 страницы1969 - Earth Art Exhibition - CatalogueRaul Lacabanne100% (2)

- "Happenings" in The New York SceneДокумент6 страниц"Happenings" in The New York SceneFarhad Bahram100% (1)

- The Elements of Typographic Style, Robert BringhurstДокумент353 страницыThe Elements of Typographic Style, Robert BringhurstShamb HalaОценок пока нет

- Nicholas Bourriaud - PostproductionДокумент45 страницNicholas Bourriaud - PostproductionElla Lewis-WilliamsОценок пока нет

- Joseph Beuys' Sculptural Imagination Installation ExploredДокумент25 страницJoseph Beuys' Sculptural Imagination Installation ExploredSara Yahvé100% (2)

- Made in TokyoДокумент20 страницMade in Tokyoricardo80% (5)

- Studies in Eastern European Cinema 1.1Документ132 страницыStudies in Eastern European Cinema 1.1Intellect BooksОценок пока нет

- Jackson PollockДокумент4 страницыJackson Pollockchurchil owinoОценок пока нет

- Art History Journal Explores Concept of Flatness in Modern and Postmodern ArtДокумент16 страницArt History Journal Explores Concept of Flatness in Modern and Postmodern ArtAnonymous wWRphADWzОценок пока нет

- Journal of Visual Arts Practice: Volume: 6 - Issue: 3Документ106 страницJournal of Visual Arts Practice: Volume: 6 - Issue: 3Intellect Books90% (10)

- Share Handbook For Artistic Research Education High DefinitionДокумент352 страницыShare Handbook For Artistic Research Education High Definitionana_smithaОценок пока нет

- John Barth - The Literature of ExhaustionДокумент7 страницJohn Barth - The Literature of ExhaustionAlexandra AntonОценок пока нет

- The Provincialism Problem: Then and NowДокумент27 страницThe Provincialism Problem: Then and NowstillifeОценок пока нет

- HAL FOSTER After The White CubeДокумент5 страницHAL FOSTER After The White CubeGuilherme CuoghiОценок пока нет

- Image Matter: Art and Materiality PDFДокумент1 страницаImage Matter: Art and Materiality PDFMIRIADONLINE0% (1)

- Art After ModernismДокумент21 страницаArt After ModernismpaubariОценок пока нет

- Hein, Hilde, What Is Public Art?: Time, Place, and MeaningДокумент8 страницHein, Hilde, What Is Public Art?: Time, Place, and MeaningAnonymous 07iOgJ52ozОценок пока нет

- Reading Comprehension Andy WarholДокумент4 страницыReading Comprehension Andy WarholStefan JosephОценок пока нет

- The Evolution of Kinetic Art and Its Connection to TechnologyДокумент9 страницThe Evolution of Kinetic Art and Its Connection to TechnologyFabiana MarottaОценок пока нет

- Video art - A concise history of the emerging art formДокумент5 страницVideo art - A concise history of the emerging art formEsminusОценок пока нет

- Sculpture and The Sculptural by Erick KoedДокумент9 страницSculpture and The Sculptural by Erick KoedOlena Oleksandra ChervonikОценок пока нет

- Abstract ExpressionismДокумент3 страницыAbstract ExpressionismKeane ChuaОценок пока нет

- Pop Art and PostmodernismДокумент27 страницPop Art and Postmodernismlookata100% (1)

- Annasophie Springer Volumes The Book As Exhibition PDFДокумент10 страницAnnasophie Springer Volumes The Book As Exhibition PDFMarianaОценок пока нет

- Journal of Media Practice: Volume: 9 - Issue: 1Документ78 страницJournal of Media Practice: Volume: 9 - Issue: 1Intellect BooksОценок пока нет

- Curatorial and Artistic ResearchДокумент15 страницCuratorial and Artistic ResearchvaldigemОценок пока нет

- The History of Futurism: The Precursors, Protagonists, and LegaciesОт EverandThe History of Futurism: The Precursors, Protagonists, and LegaciesPh. D BuelensОценок пока нет

- History of Art Development of Art in PenangДокумент13 страницHistory of Art Development of Art in PenangOliver WongОценок пока нет

- Andy WarholДокумент1 страницаAndy Warholbgmarie25Оценок пока нет

- Andy Warhol AssigmentДокумент6 страницAndy Warhol AssigmentMaya HaldorsenОценок пока нет

- Joram Mariga and Stone SculptureДокумент6 страницJoram Mariga and Stone SculpturePeter Tapiwa TichagwaОценок пока нет

- Impact of Hippies on Nepalese SocietyДокумент4 страницыImpact of Hippies on Nepalese SocietyKushal DuwadiОценок пока нет

- Hunting Public ArtДокумент7 страницHunting Public ArtSetarehDerakhshanОценок пока нет

- 2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMДокумент187 страниц2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMMirtes OliveiraОценок пока нет

- POGGIOLI, Renato. "The Concept of A Movement." The Theory of The Avant-Garde 1968Документ13 страницPOGGIOLI, Renato. "The Concept of A Movement." The Theory of The Avant-Garde 1968André CapiléОценок пока нет

- Public Art As PublicityДокумент4 страницыPublic Art As PublicityIeda MarçalОценок пока нет

- Chua Mia TeeДокумент6 страницChua Mia TeeMelinda BowmanОценок пока нет

- Toward An Understanding of Sculpture As Public ArtДокумент20 страницToward An Understanding of Sculpture As Public ArtDanial Shoukat100% (1)

- Decolonizing Curatorial Lepeck FF PDFДокумент16 страницDecolonizing Curatorial Lepeck FF PDFNicolas Licera VidalОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Education Through Art: Volume: 3 - Issue: 3Документ86 страницInternational Journal of Education Through Art: Volume: 3 - Issue: 3Intellect Books100% (1)

- Art & Aesthetics: Brief HistoryДокумент8 страницArt & Aesthetics: Brief HistoryShashwata DattaОценок пока нет

- How Painting Became Popular AgainДокумент3 страницыHow Painting Became Popular AgainWendy Abel CampbellОценок пока нет

- Coco Fusco On Chris OfiliДокумент7 страницCoco Fusco On Chris OfiliAutumn Veggiemonster WallaceОценок пока нет

- From Faktura To FactographyДокумент39 страницFrom Faktura To FactographyLida Mary SunderlandОценок пока нет

- Women Art and Power by Yolanda Lopéz and Eva BonastreДокумент5 страницWomen Art and Power by Yolanda Lopéz and Eva BonastreResearch conference on virtual worlds – Learning with simulationsОценок пока нет

- Mondrian Neoplasticism...Документ3 страницыMondrian Neoplasticism...mica011Оценок пока нет

- Salvador DaliДокумент2 страницыSalvador DaliSaket DiwakarОценок пока нет

- PPA ResumeДокумент1 страницаPPA ResumegabrielleОценок пока нет

- RESUMEДокумент2 страницыRESUMEgabrielleОценок пока нет

- The Ebb and Flow of FDIДокумент3 страницыThe Ebb and Flow of FDIgabrielleОценок пока нет

- ResumeДокумент2 страницыResumegabrielleОценок пока нет

- Art As An Asset ClassДокумент10 страницArt As An Asset ClassgabrielleОценок пока нет

- Z Thesis SynopsisДокумент22 страницыZ Thesis SynopsisAfsheen NaazОценок пока нет

- Esther and The King Color by NumberДокумент2 страницыEsther and The King Color by Numbermarilyn micosaОценок пока нет

- Spy GlassДокумент2 страницыSpy GlassSarin100% (1)

- ARTS Week 3Документ3 страницыARTS Week 3Gladz Aryan DiolaОценок пока нет

- Dancing Steps PDFДокумент18 страницDancing Steps PDFVlad VladОценок пока нет

- CubismДокумент4 страницыCubismCassie CutieОценок пока нет

- Minimalism and Biography Author(s) : Anna C. Chave Source: The Art Bulletin, Mar., 2000, Vol. 82, No. 1 (Mar., 2000), Pp. 149-163 Published By: CAAДокумент16 страницMinimalism and Biography Author(s) : Anna C. Chave Source: The Art Bulletin, Mar., 2000, Vol. 82, No. 1 (Mar., 2000), Pp. 149-163 Published By: CAANicolás Perilla ReyesОценок пока нет

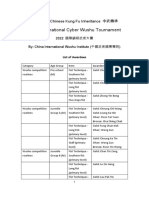

- List of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentДокумент11 страницList of Awardees - 2022 International Cyber Wushu TournamentMOUSTAFA KHEDRОценок пока нет

- Art History Thesis StatementsДокумент7 страницArt History Thesis Statementszpxoymief100% (2)

- QSN Paper XI Fine Arts-2Документ2 страницыQSN Paper XI Fine Arts-2architthakur1508Оценок пока нет

- Botchan by Natsume Soseki Ver Mori 4Документ24 страницыBotchan by Natsume Soseki Ver Mori 4tsurukyo092961Оценок пока нет

- Filipino Filmmaker Known for Critiques of NeocolonialismДокумент2 страницыFilipino Filmmaker Known for Critiques of Neocolonialismjoe blowОценок пока нет

- Julie MehretuДокумент7 страницJulie MehretuChristopher ServantОценок пока нет

- Critica de La Razon Andina Critique of AДокумент11 страницCritica de La Razon Andina Critique of AAlejandro Barrientos SalinasОценок пока нет

- Manual Display Panel - Timber - Cersanit - enДокумент13 страницManual Display Panel - Timber - Cersanit - enCsibi ErvinОценок пока нет

- Slidw Group 009 Yarn Structure AnalysisДокумент59 страницSlidw Group 009 Yarn Structure AnalysisAliAhmadОценок пока нет

- Scheme Art Grade 1 Term 2Документ3 страницыScheme Art Grade 1 Term 2libertyОценок пока нет

- Speed Kicking Scoring GuidelinesДокумент2 страницыSpeed Kicking Scoring Guidelinesina asiantkdОценок пока нет

- Courtright, Nicola (1996), 'Origins and Meanings of Rembrandt's Late Drawing Style,'. The Art Bulletin 78 (3) 485-510 PDFДокумент28 страницCourtright, Nicola (1996), 'Origins and Meanings of Rembrandt's Late Drawing Style,'. The Art Bulletin 78 (3) 485-510 PDFArtur Lima FlosiОценок пока нет

- Scripts Tips LinksДокумент3 страницыScripts Tips LinksshashankОценок пока нет

- Pamplet Menara Condong EngДокумент2 страницыPamplet Menara Condong EngEr Chun Ren100% (1)

- English 10: Quarter 2 - Week 8Документ86 страницEnglish 10: Quarter 2 - Week 8Shania Erica GabuyaОценок пока нет