Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Prevention and Management of Infants With Suspected or Proven Neonatal Sepsis - AAP 2013

Загружено:

Juan Pablo Dianderas MarengoАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Prevention and Management of Infants With Suspected or Proven Neonatal Sepsis - AAP 2013

Загружено:

Juan Pablo Dianderas MarengoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Prevention and Management of Infants With

Suspected or Proven Neonatal Sepsis

In 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, American

Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Nurse-Midwives,

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American

Society for Microbiology published revised group B streptococcal

(GBS) guidelines entitled Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: revised guidelines from CDC 2010 in the Morbidity

and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR).1 The recommendations were

endorsed by all the collaborating organizations including AAP after

review by the Committee on Infectious Diseases (COID) and the Committee on Fetus and Newborn (COFN) and after AAP Board approval. In

the report, a revised algorithm for Secondary prevention of earlyonset group B streptococcal disease was included. This algorithm

represented the expert opinions of the technical working group (based

on current literature available at that time). In 2011, the COID and the

COFN published a policy statement in Pediatrics that was in agreement

with the 2010 GBS guidelines and included the same algorithm.2

In the spring of 2012, the COFN published a clinical report containing

management guidelines entitled Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset neonatal sepsis.3 The 2012 COFN document includes guidance on laboratory evaluations and treatment

duration, which were not addressed in the 2010 GBS prevention

guidelines. The algorithms at the end of the COFN report differed from

those in the 2010 guidelines published in the MMWR.1 The discordance

in the algorithms prompted questions by the pediatric community as

to which recommendations to follow.

AUTHORS: Michael T. Brady, MD,a and Richard A. Polin, MDb

a

Nationwide Childrens Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; and bCollege of

Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New

York

KEY WORDS

neonatal sepsis, group B streptococcus, prevention, treatment

ABBREVIATIONS

AAPAmerican Academy of Pediatrics

CBCcomplete blood cell

COFNCommittee on Fetus and Newborn

COIDCommittee on Infectious Diseases

GBSgroup B streptococcal

MMWRMorbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Opinions expressed in these commentaries are those of the

authors and not necessarily those of the American Academy of

Pediatrics or its Committees.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2013-1310

doi:10.1542/peds.2013-1310

Accepted for publication Apr 24, 2013

Address correspondence to Michael T. Brady, MD, 700 Childrens

Dr, AB 7048, Columbus, OH 43205. E-mail: michael.brady@

nationwidechildrens.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright 2013 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have

no nancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

The purpose of this commentary is to clarify AAP policy. Discordant

algorithms for secondary prevention of GBS were published in 2

separate policy statements.2,3 This commentary includes the algorithm that has been approved as current AAP policy. Providing a single algorithm will avoid confusion and ensure that the guidelines

achieve their desired effects.

The COFN and the COID strongly support the recommendations made in

the 2010 prevention guidelines approved by the AAP and the other

collaborating organizations (secondary prevention of GBS algorithm

representing current AAP policy is attached in Fig 1). However, the COFN

notes that in some situations, other approaches might be considered

that differ from guidance provided in the 2010 prevention guidelines.

The following recommendations include the recommendations from the

2010 MMWR publication and those made by the COFN:

1. Neonates who have signs of sepsis should receive broad-spectrum

antimicrobial agents.

2. Healthy-appearing preterm and term infants born to women with

suspected chorioamnionitis should receive a blood culture at

166

BRADY and POLIN

Downloaded from by guest on February 12, 2016

COMMENTARY

the 2010 GBS prevention guidelines recommend a limited evaluation (blood culture and complete

blood cell [CBC] count with differential at birth or 6 to 12 hours

of age) and hospital observation

for 48 hours. The COFN recommends hospital observation for

48 hours in this circumstance

(without further testing or cultures). However, when close observation is not possible, the

COFN recommends a laboratory

evaluation.

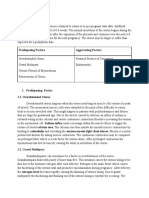

FIGURE 1

Secondary prevention of GBS disease.1,2 Algorithm for the prevention of early-onset GBS infection in

the newborn. (Adapted with permission from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention

of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease

from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59 [RR-10]:132.) IV, intravenously. aFull diagnostic

evaluation includes a blood culture; CBC count, including white blood cell differential and platelet

counts; chest radiograph (if respiratory abnormalities are present); and lumbar puncture (if the

patient is stable enough to tolerate procedure and sepsis is suspected). bAntibiotic therapy should

be directed toward the most common causes of neonatal sepsis, including intravenous ampicillin for

GBS and coverage for other organisms (including Escherichia coli and other gram-negative

pathogens) and should take into account local antibiotic-resistance patterns. cConsultation with

obstetric providers is important in determining the level of clinical suspicion for chorioamnionitis.

Chorioamnionitis is diagnosed clinically, and some of the signs are nonspecic. dLimited evaluation

includes blood culture (at birth) and CBC count with differential and platelets (at birth and/or at

612 hours after birth). eGBS prophylaxis is indicated if 1 or more of the following is true: (1) mother

is GBS-positive late in gestation and is not undergoing cesarean delivery before labor onset with intact

amniotic membranes; (2) GBS status is unknown and there are 1 or more intrapartum risk factors,

including ,37 weeks gestation, rupture of membranes for $18 hours, or temperature of $100.4F

(38.0C); (3) GBS bacteriuria during current pregnancy; or (4) history of a previous infant with GBS

disease. fIf signs of sepsis develop, a full diagnostic evaluation should be performed, and antibiotic

therapy should be initiated. gIf $37 weeks gestation, observation may occur at home after 24 hours

if other discharge criteria have been met, there is ready access to medical care, and a person who

is able to comply fully with instructions for home observation will be present. If any of these

conditions is not met, the infant should be observed in the hospital for at least 48 hours and until

discharge criteria have been achieved. hSome experts recommend a CBC count with differential and

platelets at 6 to 12 hours of age.

birth, a complete blood count with

differential 1/2 C-reactive protein

at age 6 to 12 hours. These infants

should be treated with broadspectrum antimicrobial agents.

3. For well-appearing infants $37

weeks gestation whose mother did

not have suspected chorioamnionitis,

but who did have an indication for

intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis

and did not receive at least 4 hours

of intrapartum penicillin, ampicillin

or cefazolin:

a. The 2010 GBS prevention guidelines and the 2012 COFN statement agree that infants who are

well appearing can be observed

without additional testing if duration of rupture of membranes

is ,18 hours. The COFN believes

that infants at 35 to 36 weeks

gestation can be treated similarly if the physical examination

is normal.

b. If duration of membrane rupture is

$18 hours and IAP is inadequate,

PEDIATRICS Volume 132, Number 1, July 2013

Downloaded from by guest on February 12, 2016

4. For well-appearing infants ,37

weeks gestation whose mother did

not have suspected chorioamnionitis,

but who did have an indication for

IAP and did not receive adequate

prophylaxis, the 2010 GBS prevention guidelines recommend a limited evaluation (blood culture and

CBC count) and hospital observation for 48 hours. The COFN also

recommends a limited evaluation,

but no blood culture unless antibiotics are started because of abnormal laboratory data.

5. The 2010 GBS prevention guidelines

do not address the duration of antibiotic therapy. The COFN makes

recommendations for the duration

of antimicrobial therapy based on

the results of laboratory testing.

Healthy-appearing infants without

evidence of bacterial infection should

receive broad-spectrum antimicrobial

agents for no more than 48 hours.

In small preterm infants, some

may continue antibiotics for up

to 72 hours while awaiting bacterial culture results.

Published data to support recommendations for prevention and management of newborn sepsis are limited.

However, success of the GBS prevention

guidelines provides evidence that reductions in early-onset GBS disease

have been possible by the development

of consensus guidelines with consistent

167

implementation.1 The COFNs 2012 recommendations complement the 2010

GBS prevention guidelines by providing

additional treatment information that is

not addressed in the 2010 prevention

guidelines. These should provide clinicians with guidance for optimal duration

of antimicrobial therapy and reduce

excess exposure to broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy in healthy-appearing

uninfected infants who had empirical

antimicrobial therapy initiated.

2. Committee on Infectious Diseases; Committee on

Fetus and Newborn, Baker CJ, Byington CL, Polin

RA. Policy statementRecommendations for

prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal

(GBS) disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):611616

3. Polin RA; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Management of neonates with

suspected or proven early-onset neonatal sepsis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):1006

1015

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal diseaserevised guidelines from CDC,

2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-10):

136

CANINE LICKS OF LOVE SHAPE HUMAN BIOME: Theres nothing like coming home

at the end of the day to nd mans best friend there to greet you. Dogs provide

unconditional love and affection, and it appears that their welcoming kisses

may do more than just strengthen the relationship between human and animal.

As reported on an NPR health news blog (Shots: April 18, 2013), a recent study

indicates that dog owners share a common bond the bacteria on their skin.

In their investigation of 159 individuals living in 17 households, researchers

found that dog owners living in separate households share a common bacterial linkage through their canine companions. Actinobacteria and Betaproteobacteria found in soil and on dogs tongues, respectively, were present on

dog owners skin in greater amounts than in those who did not own dogs.

Unsurprisingly, the type and amount of bacteria on an owners skin were most

closely related to that of their own pooch. This effect was only observed in the

adult dog owner population (18-59 years of age); the presence of other

household pets, including cats, had no signicant effect on owner microbiota.

While our canine furry friends may shape our skin environment, additional

research is necessary to better dene how these bacteria inuence our health.

Noted by Leah H. Carr, BS, MS-IV

168

BRADY and POLIN

Downloaded from by guest on February 12, 2016

Prevention and Management of Infants With Suspected or Proven Neonatal

Sepsis

Michael T. Brady and Richard A. Polin

Pediatrics 2013;132;166; originally published online June 10, 2013;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-1310

Updated Information &

Services

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

/content/132/1/166.full.html

References

This article cites 3 articles, 2 of which can be accessed free

at:

/content/132/1/166.full.html#ref-list-1

Citations

This article has been cited by 6 HighWire-hosted articles:

/content/132/1/166.full.html#related-urls

Post-Publication

Peer Reviews (P3Rs)

2 P3Rs have been posted to this article /cgi/eletters/132/1/166

Subspecialty Collections

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Fetus/Newborn Infant

/cgi/collection/fetus:newborn_infant_sub

Neonatology

/cgi/collection/neonatology_sub

Permissions & Licensing

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2013 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on February 12, 2016

Prevention and Management of Infants With Suspected or Proven Neonatal

Sepsis

Michael T. Brady and Richard A. Polin

Pediatrics 2013;132;166; originally published online June 10, 2013;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-1310

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

/content/132/1/166.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2013 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on February 12, 2016

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- SCI - Learning Packet - Biology Week 5Документ13 страницSCI - Learning Packet - Biology Week 5Pal, Julia HanneОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Original Prevention of Sickness PamphletДокумент88 страницThe Original Prevention of Sickness PamphletGeorge Singleton100% (4)

- Womens Fitness UK 08.2021Документ92 страницыWomens Fitness UK 08.2021Diseño ArtisОценок пока нет

- Fdar Samples PresentationДокумент29 страницFdar Samples PresentationKewkew Azilear92% (37)

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis Case StudyДокумент5 страницDiabetic Ketoacidosis Case Studyjc_albano29100% (7)

- Family DeclarationДокумент5 страницFamily DeclarationVanlal MuanpuiaОценок пока нет

- Guided Home Module: Psychosocial Support Activities For Elementary Learners Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)Документ36 страницGuided Home Module: Psychosocial Support Activities For Elementary Learners Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)Jennyhyn cruz75% (4)

- Essential Care of Newborn at BirthДокумент32 страницыEssential Care of Newborn at Birthastha singh100% (1)

- Reaching OutДокумент353 страницыReaching OutDebayan NandaОценок пока нет

- Bacterial Vaginosis Treatment - UpToDateДокумент12 страницBacterial Vaginosis Treatment - UpToDateAlex Esteban Espinoza CevallosОценок пока нет

- Lab 7 HIV Detection Using ELISAДокумент24 страницыLab 7 HIV Detection Using ELISAAhmed AbedoОценок пока нет

- Queenie Rose Domingo - Drug Study (Silver Sulfadiazine)Документ1 страницаQueenie Rose Domingo - Drug Study (Silver Sulfadiazine)Sheryl Ann Barit PedinesОценок пока нет

- Assessment of Knowledge Attitude and Perception of Dental Students Towards Obesity in Kanpur CityДокумент6 страницAssessment of Knowledge Attitude and Perception of Dental Students Towards Obesity in Kanpur CityAdvanced Research PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Chapter 10Документ10 страницChapter 10The makas AbababaОценок пока нет

- Epoch Elder Care Provides High Quality Assisted Living HomesДокумент17 страницEpoch Elder Care Provides High Quality Assisted Living HomesMahesh MahtoliaОценок пока нет

- Product Brochure 2023-2024 en LRДокумент23 страницыProduct Brochure 2023-2024 en LRaf8009035Оценок пока нет

- 4.ethico - Legal in Older AdultДокумент46 страниц4.ethico - Legal in Older AdultShazich Keith LacbayОценок пока нет

- Detection of NoncomplianceДокумент12 страницDetection of Noncompliancesomayya waliОценок пока нет

- Difhtheria in ChildrenДокумент9 страницDifhtheria in ChildrenFahmi IdrisОценок пока нет

- Ethical Considerations in Transcultural Nursing.Документ1 страницаEthical Considerations in Transcultural Nursing.Maddy LaraОценок пока нет

- EO-GA-32 Continued Response To COVID-19 IMAGE 10-07-2020Документ7 страницEO-GA-32 Continued Response To COVID-19 IMAGE 10-07-2020Jakob RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Format Nutritional StatusДокумент43 страницыFormat Nutritional StatusDirkie Meteoro Rufin83% (6)

- Discharge PlanДокумент2 страницыDischarge Plan2G Balatayo Joshua LeoОценок пока нет

- Cupuncture: Victor S. SierpinaДокумент6 страницCupuncture: Victor S. SierpinaSgantzos MarkosОценок пока нет

- Fecal Occult BloodДокумент9 страницFecal Occult BloodRipu DamanОценок пока нет

- FNCPДокумент5 страницFNCPGwen De CastroОценок пока нет

- Startup StoryДокумент1 страницаStartup StorybmeghabОценок пока нет

- List of Private Hospitals and Diagnostic Centers Approved by INSAДокумент16 страницList of Private Hospitals and Diagnostic Centers Approved by INSAvijay sainiОценок пока нет

- FoodДокумент3 страницыFoodDiego EscobarОценок пока нет

- What Is Subinvolution?Документ5 страницWhat Is Subinvolution?Xierl BarreraОценок пока нет