Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

ModernAge 56.1 3essays AnUnawarenessOfWhatIsMissing

Загружено:

falsifikatorОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ModernAge 56.1 3essays AnUnawarenessOfWhatIsMissing

Загружено:

falsifikatorАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ESSAY

AN (UN)AWARENESS OF

WHAT IS MISSING

taking issue with habermas

W. Julian Korab-Karpowicz

any thinkers of the Enlightenment

considered religion superfluous.1

Human life was meant to be fully shaped by

the power of reason. Modern individuals had

to be freed from dogma and other religious

restrictions. Such views can also be found in

Jrgen Habermas, one of the most persistent

and influential exponents of the tradition of

Enlightenment. In recent years, however,

Habermass position toward religion has

changed. He now believes that religions are

not going to disappear and that they will

continue to play an important role in future

societies. Highly symptomatic of this new

attitude of the German philosopher was his

discussion with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

(later Pope Benedict XVI) at the Catholic

Academy in Munich in January 2004, as

well as a dialogue with four philosophers

from the Jesuit School of Philosophy in February 2007.2 The latter has been published

in an English translation under the title An

Awareness of What Is Missing: Faith and Reason in a Post-secular Age.3

Habermas claims that although modern

thought treats revelation and religion as

something alien and extraneous,4 religion is

still present in todays world. The memorable

events of 9/11 confirmed that modernist

secular society is not the end of history, and

that the theme of religions and civilizations,

and of potential conflicts between them, is

still alive. There are new global, often violent religious organizations whose mind-set

clashes with fundamental convictions of

modernity.5 There is a growing conflict

between fundamentalist religion and the

secular state.

In the essay An Awareness of What

Is Missing, as in his earlier work Philosophical Discourse of Modernity,6 Habermas

defends a modern worldview and is critical

W. Julian Korab-Karpowicz is a philosopher and a political thinker, professor of philosophy at Lazarski

University in Warsaw, and author of Love and Wisdom and On the History of Political Philosophy.

19

MODERN AGE

of postmodernism. He expresses a desire

to mobilize modern reason against the

defeatism lurking within itthis defeatism which we encounter today...in the

postmodern radicalization of the dialectic

of the Enlightenment.7 However, his later

writing no longer shares the optimism of the

Discourse concerning a successful completion

of this enterprise. It begins with a strange

scene: secular intellectuals in a church bid

farewell to a deceased friend, an agnostic

who rejected any profession of faith, taking part in his funeral ceremony, at which

there is no priest, no blessing, and no word

amen. The scene may perhaps rightly

depict the spiritual emptiness of secularized

Western humanity and its desire to return

to at least the external manifestations of

religion, but Habermas does not interpret it

this way. He states that the funeral ceremony

may tell us something about secular reason,

namely that it is unsettled by the opaqueness

of its merely apparently clarified relation to

religion.8 This relation is not a compromise

between what Habermas believes are two

irreconcilable elements: an anthropocentric orientation and theocentric thinking. It

is rather that the two engage in a dialogue,

that they speak with each other, rather

than merely about one another.9

To be partners in a dialogue, it is indispensable for Habermas that the religious side

must accept the authority of natural reason,

while secular reason may not set itself up as

the judge concerning truths of faith.10 Nevertheless, purely formal acceptance of this

demand by religious citizens is not enough

to establish a liberal democracy, whose legitimacy is founded on convictions. It must be

based on normative foundations which can

be justified neutrally towards worldviews.11 It

means that it must actually be postreligious

and postmetaphysical.

The consequences of 9/11 have thus only

20

WINTER 2014

partially reached the consciousness of the

German thinker. He believes that religious

citizens of a liberal democracy should accept

internallyand therefore not under external compulsion but rather for reasons of

its ownthe neutrality of the state toward

worldviews. This practically implies not only

the actual consent of citizens to recognize

the equality of all religions and to separate

scientific claims from articles of faith but also

the cleansing of the public space of religious

symbols and values. Religious utterances

are to have the right to a place in the public

domain only if they are translated into morally motivated rational belief.12 They need to

be expressed in the language understood by

a secular public, for whom their assessment

is not based on faith in God but knowledge

based on facts.

It should be first noted that the demand

that the religious side accepts the authority

of natural reason can be approved only

by religious traditions in which reason has

been regarded as autonomous in relation

to faith, and this primarily means Christianity. In spite of frequent interventions of

religious authorities, the trend toward the

affirmation of the independence of reason

from faith increasingly predominated in

European history. This allowed culture and

politics in Europe to become independent

from religion, and on the other hand to draw

from it moral and spiritual inspiration. The

result of this complex relationship was an

unparalleled dynamism in the development

of Western civilization.

uch an independence of reason from

faith is, however, not present in the

civilizations of the East, and particularly

in Islamic civilization. In Islam the whole

of life is subordinated to the sacred law of

sharia, and to break free from this law and

be guided by natural reason is equivalent, in

AN (UN)AWARENESS OF WHAT IS MISSING

the opinion of Muslim scholars, to ignorance

of divine guidance, jahiliyyaintellectual

and moral corruption.13 Habermass demand

that the religious side accepts the authority

of natural reason can then be accepted by

Christians, but it will not find acceptance by

Muslims. The practical implementation of

this demand could thus lead to an asymmetry between religions. In Western society it

would result in the weakening of religion: its

removal from public spaces and a consequent

secularization, which the Eastern religious

communities would strongly refuse.

While exploring the meaning of modernity, Habermas points out that while it

creates a new culture of freedom, it also

results in the breakdown of traditional

society into individuals and groups who

often have conflicting interests. This breakdown in solidarity increases all the more

inexorably the deeper the imperatives of

the market...[which] penetrate ever more

spheres of life and force individuals to adopt

an objectivizing standpoint in their dealing

with each other.14 Secular rational morality

developed by modern thinkers is aimed at

individuals rather than at communities and

does not foster any impulse toward solidarity. Traditional religious consciousness, by

contrast, preserves the spirit of community

from which impulses toward action in solidarity can be derived.

The translation of certain religious utterances or claims into a secular language of

morally motivated rational belief is thus

important from the point of view of Habermass project. While taking on the role of the

leading defender of modern rationality, he

seems at the same time to be anxious about

it. His anxiety is reflected in the very title of

his work: An Awareness of What Is Missing (Ein Bewutsein von dem, was fehlt).

Despite so many contributions to the field

of technology and social organization, with

which it can be associated, modern reason

has failed to awaken, and to keep awake, in

the minds of secular subjects, an awareness

of the violations of solidarity throughout the

world, an awareness of what is missing, of

what cries out to heaven.15

abermas regrets what he believes is

missing in the modern age, namely,

human solidarity. Nevertheless, to bring it

back he does not turn to world religions.

Rather, by following Kant he tries to assimilate religion to secular reason. He believes

that there are certain religious images of

the moral wholelike the Kingdom of

God on earththat are collectively binding

ideas.16 Recognizing their utility for human

unity, he wants to deprive them of religious

content and translate them into a publicly

accessible language of secular discourse.

For the same reason, he develops his theory

of communicative action. As a result of an

exchange of views, he claims, participants in

a discourse overcome their at first subjective

views in favor of rationally motivated agreement.17 Rational consensus, intersubjective

understanding, and reciprocal recognition

are all related to Habermass hope to restore

authentic [human] self-realization, and selfdetermination in solidarity.18

However, as can be easily observed by

looking into many cases of religious sectarian violence, religion not only unites but also

divides, and in todays postsecular world,

religious sectarianism is one of the principal

sources of conflict. Therefore, religion can be

regarded as a uniting factor but only within

a given religious sect or denomination. Religions cleared of their original religious content and translated into a secular language

are in turn nothing other than the modern

ideologies that, without God, try to build

the Kingdom of God on earth. The current

global crisis, including the lack of solidarity

21

MODERN AGE

among people and the intellectual crisis that

Europe is experiencing today, is the result of

such ideologies.

Therefore, Habermass postsecular project

can be described as an ambitious attempt to

square the circle; seemingly effective and generating acclaim on both sides of the ocean but

based on wrong assumptions and doomed to

failure. Taking into account that he does not

make a proper distinction between Christianity and religions outside the circle of Western

civilization, his ideas are not only impractical

and unable to regain a lost human solidarity

but also disastrous for Europe: by undermining its Christian roots, they further weaken

its already fragile identity.

hile taking issue with Habermas

about what is missing, I would like

first to note that the theory of communicative action is nothing new. One can find

it in the dialogues of Plato. Engaged in a

conversation, their participants try to reach

an agreement. What distinguishes the

profound and at the same time often witty

Platonic dialogues from Habermass obscure

and sometimes confusing theory, however,

is that the formers goal is to achieve not

only a rational consensus but also, and more

important, to arrive at truth, goodness, and

beauty.19 In this sense the Platonic dialogues

are metaphysical.

Habermas rejects the view of Plato, Aristotle, and the subsequent classical tradition of

Western philosophy that one can find truth

through knowledge of the essence of things

and that this truth is timeless and universal.

As is the case for Hobbes and other modern thinkers, the character of truth is for

Habermas merely conventional and arbitrary, a result of an agreement. The aim of

Habermass communicative action is not a

universal truth but rational consensus. His

communicative reason is disburdened of all

22

WINTER 2014

religious and metaphysical mortgages.20 It

is based on modern secularization and deHellenization of thought.

According to Habermas, religion and

metaphysics derive from a common source,

which is the worldview revolution of the

axial age.21 Leaving aside the oddity of

the conceptafter all, religions are older

than philosophy and accompany human

beings from the beginning of their existence,

whereas Islam was born well after the axial

agethe combination of religion and metaphysics can be associated with the JudeoChristian tradition. In Christianity, in fact,

as clearly expressed by Benedict XVI in his

Regensburg lecture, there was a profound

encounter of faith and reason.22 There was

a rapprochement between Biblical faith and

Greek philosophical inquiry.23

At the dawn of the modern era, with the

rise of the Reformation, there was, in turn, a

call for the de-Hellenization of Christianity,

to offset the side of reason and to make place

for faith alone. At the same time there was a

modern self-restraint on the part of reason,

which is reflected in the first Critique of

Immanuel Kant, subsequently radicalized by

the reduction of scientific knowledge to the

knowledge of facts and by the insistence that

questions about religious and ethical values

go beyond the limits of scientific inquiry.

Hence, the modern mind moved away not

only from (particularly Christian) religion

but also from metaphysics. In this way it

became postreligious and postmetaphysical.

Habermas describes the liberal constitutional state as resting on normative foundations which can be justified neutrally

towards worldviewsand that means in

postmetaphysical terms.24 Contrary to

what Habermas and many other thinkers

of modernity believe, one cannot, however,

escape from metaphysics into a postmetaphysical thinking. The basic metaphysical

AN (UN)AWARENESS OF WHAT IS MISSING

question is one of the essence of the human

being. At the heart of modern rationality lies

an assumption about human nature: man

is the Cartesian subject around which the

world revolves.

This modern subjectivity is expressed at a

practical level in individualism, namely, in

thought and action aimed at ones own particularity, that is, motivated by self-interest.

Thus by recognizing human beings as creatures of interests, driven by desires, Hobbes

has rightly led Descartess thought to its logical, practical consequences. Modern reason,

which Habermas describes in his Discourse

as instrumental, is for Hobbes merely

an instrument, a calculus of utilities; with

rationality being no more than a reckoning

of the consequences of things imagined in

the mind,25 of desires, aversions, hopes, and

fears, or of possible gains or losses.

This modern concept of instrumental or

purposive rationality thus replaces the classical concept of reflective or deliberative

rationality. According to Aristotle and other

representatives of the classical traditiona

tradition born in Greece and continued by

St. Thomas Aquinas and other Christian

thinkers, and that can be described as the

tradition of virtuethe capacity for rational

reflection on what is beneficial and what

is harmful, just and unjust, is what distinguishes humans from other creatures. In

this sense a person endowed with reflective

reason, even if subjected to desires, is not

merely a creature of interests but above all

an intelligent and moral being capable of

self-reflection and self-control. People whose

character has been shaped by the practice

of virtueand to become truly virtuous,

as Christian philosophy suggests, they need

not only a good character but also faith in

Godcan control their desires and sacrifice

their personal benefits for the good of others.

The explosion of human desires is a result

of modernitysurely this escapes the attention of Habermas. It seems he does not

fully appreciate the impact exerted on the

formation of modern thought by Hobbes,

Locke, and other English thinkers, for in his

Philosophical Discourse of Modernity he does

not pay much attention to them. Yet, in the

assumption that all humans are fundamentally the sameself-interested, pleasureseeking individuals whose behavior is modified neither by virtue nor by natural law nor

by religious belief, with the same cause having the same effect on everyonethe ideas

of Hobbes come to the fore. They grow out

of the radical rejection of the classical tradition. Similarly, Hobbess opponent Locke,

who is often described as a father of liberalism, is not a classical thinker, but modern.

His modernity is revealed not only in his

modern methodology, an attempt to derive

all knowledge from experience, but especially in his concept of man. Like Hobbes he

considers human beings as individuals who

are moved by desires and who, instead of

cultivating virtue, pursue happiness by seeking pleasure and avoiding pain.

he same Hobbesian concept of human

nature can be found in the utilitarianism of Bentham and his followers and in

todays positivist or behavioral social sciences. In such systems of thought an attempt

is made to reduce the complexity of the

classical view of politics. The constitutional

character of political institutions is preserved,

but politics is no longer about morality or

religion: it becomes a power game or a play

of interests. Moreover, this view of human

beings as self-interested, passion-driven

individuals is not confined to the realm of

theory. With a model of education in place

that is no longer based on classical ideas but

increasingly dependent on positivist assumptions and methodology, such a picture is

23

MODERN AGE

internalized during many years of schooling.

It therefore influences both thinking and,

ultimately, actual human behavior. Subject

to social engineering and convinced that

desires, and other passions of man, are in

themselves no sin,26 individuals make their

goal the maximization of utility: they just

want to get what they want without paying

attention to moral restraints.

Whether it be desire, self-interest, will to

power, or class strugglethinkers of modernity make an attempt to reduce the complex

picture of human affairs to a simple principle. Once they discover this principle, they

try to implement and enforce it. The boundary between classicism and modernity is set

by voluntarism. Political and social reality

is voluntarily interpreted as an entity whose

creation and existence is based solely on the

power of free choice of the human will. The

search for truth is replaced by the will to

actthe shaping of human beings and the

constructing of state and society. The main

purpose of thinking is no longer to understand but rather to transform reality. We can

find this idea not only in Marxism, in which

philosophy is subordinated to the task of a

revolutionary transformation of society into

one that is classless and free from exploitation, but also in liberalism, which transforms

people into the same self-interested individuals and society into a platform for the purpose of obtaining private goals.

There is also such thinking in Habermas,

for whom the modern state is a secular state

that functions as an intellectual formation.27 Thus, as we can suppose, the state

forms the intellects of its citizens, freeing

them from the burden of religion and metaphysics. And when, in light of the events

of 9/11 and their consequences, a postreligious world turns out to be impossible to

obtain, he wants at least that world religions

accept the authority of natural reason,

24

WINTER 2014

approve the neutrality of the state toward

worldviews, respect freedom of religion and

conscience, and serve the project of rebuilding the lost human solidarity.

The end of the Cold War, the selfpredicted triumph of liberal democracy, and

the accelerated processes of globalization

have stimulated human desires to an extent

previously unknown. Modern secularized

individualsindividuals without God,

without virtue, and without mannersare

creatures of interests who today populate

large parts of the world. How then can

they arrive at intersubjective agreement and

mutual recognition? This may be possible

but only through the community of interests, not on a moral plane. However, given

that human interests and points of view are

often divergent, there is no great hope in

obtaining consent.

he world today, as daily news confirms,

is the reality of constant uncertainty

and endless conflict: when one ends, a new

one begins. Therefore, Habermass theory

of communicative action cleansed of all

religious and metaphysical elements seems

a great misunderstanding. Directed toward

their particular interests, egoistical individuals are not able to achieve a sustainable rational consensus. The human being is the best

animal when perfected by virtue, but when

separated from law and justice, he may be

the worst, as Aristotle declared; and without

God, even the best virtues turn into vices, as

St. Augustine added.

In liberal society, whose theory was initially presented by Lockein an environment where the individual is freed from

state control, as well as the influence of

religion and traditional tiespeople have

unlimited possibilities to pursue their own

goals, getting rich and satisfying their individual desires, shaping their environment

AN (UN)AWARENESS OF WHAT IS MISSING

and transforming themselves. Their desires

are not only multiplied but, due to peer and

public pressure, encouraged and so ordered

as to lead to economic success.28 While

Hobbes, in his unrelenting drive to impose

order, suppresses human desires through

the power of absolute government, Locke,

in his liberalism, releases them from all

restraint and directs them toward whatever

riches the world has to offer.

Modernity is today challenged by postmodernity. Certainly thinkers such as Martin

Heidegger, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and others, mentioned by Habermas

in his Discourse, contributed to the development of postmodern thought. Linking

postmodernism with the criticism of modern

rationality and an attempt to transcend its

limitations, however, is not enough to characterize this ideological formation.

It is obvious that once life in modernity,

especially politics and economics, is separated from religion and morality, it invites

critique. The common people, involved in

daily toil, unlike many of their leaders and

professors, never forget to ask questions

about what is just and unjust. Postmodernity

thus can partially be regarded as an attempt

to reintroduce an ethical discourse into

modernity, but since the critical discourse

on the one hand takes the form of religious

fundamentalism, and on the other hand is

expressed in the language of the dialectic

of oppression, it is far from classical ethics

or traditional religion. Traditional society,

based on the idea of naturally differentiated

human beings, is challenged by modernity,

which replaced it with an artificial construct:

a group of homogeneous individuals melted

by social contract into a unity, into one

people, one body politic, under one supreme

government.29 Postmodernity in turn

deconstructs the modern concept of unity

through its notion of division.

The term diversity is often used in reference

to this division. Nevertheless, diversity in the

postmodern sense refers to ethnic, cultural,

and sexual forms of diversity and by no

means refers to qualitatively dissimilar persons, divided into traditional social groups

or classes. The existence of any such persons,

especially of the aristocracy, is excluded from

the modern project and certainly from its

postmodern radicalization. Postmodernity

stands at the same time for globalization,

posttraditionalism, postnationalism, and

post-Eurocentrism. It eradicates the rest of

the local and national traditions. Unique

local and national cultures are replaced by

global multiculturalism and the celebration

of new differences.

Postmodernity, we should also add, though

critical of modernity, is in fact a continuation of the unfinished modern project. Like

modernity, it is characterized by voluntarism.

In both modernity and postmodernity, social

reality has created a decisive force of will,

embodied in the Hobbesian absolute sovereign, who can be equally represented by either

the single-person tyrant or the power-hungry

people. With reference to the latter, the result

of the democratization of sovereignty is

ubiquitous disciplinary power.30 Therefore,

instead of Habermass idealized impartial

rational consensus, we would instead find

political correctness and the conformity

pertinent to it. Instead of communication or

dialogue aimed at mutual recognition and

consensus, groups impose on majorities their

skillfully fabricated and often highly controversial discourses. This is done by lobbies and

other organizations representing particular

social, political, and economic interests.

e-Hellenization in philosophy is the

work of Hobbes and his followers,

who decidedly opposed the classical tradition; secularization in turn is the process to

25

MODERN AGE

which several modern thinkers have contributed, each in his own way: Nietzsche,

Feuerbach, Marx. Secularization and deHellenization lead to a world without God

and without virtue, one in which human

beings are ruled by their desires. Already St.

Augustine noted that in the fallen man who

remains under the sway of his desires, there

is an erosion of rationality. For Locke, who,

despite his liberalism, denied tolerance to

atheists, the lack of the supreme desire,

the desire for eternal life, leads people to

moral degradation. Consequently, the disenchanted modern world without God

is not the world of true rationality, but of

the defective instrumental rationality that

serves desires and does not provide a comprehensive vision of reality. This modern

rationality expresses itself, on the one hand,

in undisputed scientific and technological

achievements, and the ongoing modernization of life; and on the other hand, in

violent conflicts, a life full of anxiety, and

the inner emptiness of modern humanity.

Its effect is not the end of history, as predicted by Hegel, Marx, and more recently

Fukuyama, but its ever faster and more

unexpected change.

In just one generation the inhabitants of the

Westwho made their own deconstruction

by becoming a people without God, without

virtue, without manners, and often without

families and without childrenare at risk

of losing their current leading economic,

political, and cultural role in the world. They

1.

2.

3.

26

WINTER 2014

have created a void that is now to be filled by

other, non-Western civilizations.

The greatest loss of modern humanity,

however, in both the West and the East, is

the loss of the human soul. By forsaking

God and virtue, and the awareness of the

proper order of things, human beings lose

themselves in superficial desires. They are

not even aware of what has been lost. The

solution is obviously not the politicized and

often violent religiosity of fundamentalism.

That only contributes further to human

degradation. To save themselves, modern

individuals must learn to know themselves

again. By deep philosophical reflection and

authentic religion, they must fill up the void

that created postreligious and postmetaphysical thought. They must in the end

rediscover their deeper selves.

One cannot live by power or desire alone.

Human beings are not one-dimensional, as

Hobbes and his followers tried to make us

believe, but in fact have many dimensions

and many needs. The classical tradition

reveals some of those. It speaks to us of

community and friendship, virtue and corruption, self-interest and self-control, justice

and order, freedom and law, happiness and

sorrow, the purposes of life and the dangers

of war. It is only through action that can be

defined as a return to origins, namely, by

creatively repeating and recalling the sources

of Western civilizationthe ideas contained

in the classical traditionthat the declining

civilization can be rebuilt.

In his work A Secular Age, Taylor associates this view with secular, self-sufficient humanists who subscribe to Enlightenment

values and deny all other life goals beyond human flourishing. He contrasts them with religious humanists (believers in

transcendence) and postmodern antihumanists (neo-Nietzscheans). He thus refers to the struggle between the secular and the

spiritual as a three-cornered battle. See Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Boston: Belknap Press, 2007), 636. In my interpretation, these three corners are represented by broader perspectives of modernity, postmodernity, and the classical tradition. Their

conflict constitutes our present experience of living within Western civilization.

Jrgen Habermas and Joseph Ratzinger, Dialektik der Sakularisierung: ber Vernunft und Religion, ed. Susanne Lossi (Freiburg

im Breisgau: Herder, 2005); Jrgen Habermas, et al., Ein Bewutsein von dem, was fehlt. Eine Diskussion mit Jrgen Habermas,

eds. Michael Reder and Josef Schmidt (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2008).

Jrgen Habermas, et al., An Awareness of What Is Missing: Faith and Reason in a Post-Secular Age, trans. Ciaran Cronin (Malden: Polity Press, 2010), 17.

AN (UN)AWARENESS OF WHAT IS MISSING

4. Habermas, An Awareness of What Is Missing, 17.

5. Ibid., 20.

6. Jrgen Habermas, Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures, trans. Frederick G. Lawrence (Malden: MIT Press,

1990). This work originally appeared in German under the title Der philosophische Diskurs der Moderne: Zwlf Vorlesungen

(Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1985).

7. Habermas, An Awareness of What Is Missing, 18.

8. Ibid., 1516.

9. Ibid., 16.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid., 21.

12. Ibid., 75.

13. Roxanne L. Euben, Mapping Modernities Islamic and Western, in Border Crossing: Toward a Comparative Political Theory,

ed. Fred R. Dallmayr (Lanham: Lexington Books, 1999), 1137.

14. Habermas, An Awareness of What Is Missing, 7374.

15. Ibid., 19.

16. Ibid.

17. Habermas, Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, 315.

18. Ibid., 318.

19. See Wladyslaw Tatarkiewicz, History of Aesthetics, vol. 1, Ancient Aesthetics, ed. J. Harrell, trans. Adam and Ann Czerniawski

(New York: Continuum, 2005), 114.

20. Habermas, Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, 316.

21. Karl Jaspers, who introduced the term axial age (German Achsenzeit), believed that in the period between 800 and 200 BC

there were revolutionary changes in the thinking of human beings in the East and the West. Born during this period were

prominent thinkers: Confucius, Lao-Tzu, Zoroaster, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and others.

22. Pope Benedict XVI, Faith, Reason and the University: Memories and Reflections (lecture, University of Regensburg, September 12, 2006). This document can be found at: http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/speeches/2006/september/

documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20060912_university-regensburg_en.html.

23. Ibid.

24. Habermas, An Awareness of What Is Missing, 2122.

25. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan: With Selected Variant from the Latin Edition of 1868, ed. Edwin Curley (Indianapolis: Hackett,

1994), 18.

26. Ibid., 77.

27. Habermas, An Awareness of What Is Missing, 21.

28. W. Julian Korab-Karpowicz, On the History of Political Philosophy (Boston: Pearson, 2012), 21113.

29. John Locke, Second Treatise on Government, ed. C. B. Macpherson (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1980), 4748.

30. Michel Foucault, Lecture Two: 14 January 1976, in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 19721977, ed.

Collin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980), 105.

27

Вам также может понравиться

- Husni Newman Modern Arabic Short Stories A Bilingual Reader PDFДокумент150 страницHusni Newman Modern Arabic Short Stories A Bilingual Reader PDFAmy McSheckОценок пока нет

- Nature, Man and God in Medieval IslamДокумент1 247 страницNature, Man and God in Medieval IslamAlina Isac Alak100% (3)

- 95500Документ276 страниц95500Yar BatohОценок пока нет

- Foreign Affairs 95.4 (July-August 2016)Документ212 страницForeign Affairs 95.4 (July-August 2016)MichaelОценок пока нет

- Rethinking World History PDFДокумент352 страницыRethinking World History PDFfalsifikator100% (2)

- Toshihiko Izutsu Ethico-Religious Consept QuranДокумент152 страницыToshihiko Izutsu Ethico-Religious Consept QuranSoak KaosОценок пока нет

- Habermas and ReligionДокумент22 страницыHabermas and ReligionfalsifikatorОценок пока нет

- Foreign Affairs - Nov-Dec 2016 - 95600Документ256 страницForeign Affairs - Nov-Dec 2016 - 95600falsifikator100% (4)

- Habermas Kierkegaard and The Nature of T PDFДокумент22 страницыHabermas Kierkegaard and The Nature of T PDFfalsifikatorОценок пока нет

- Tariq Ramadan Western Muslims and The Future of Islam PDFДокумент285 страницTariq Ramadan Western Muslims and The Future of Islam PDFibrahim aghilОценок пока нет

- How Greek Science Passed To The Arabs PDFДокумент139 страницHow Greek Science Passed To The Arabs PDFAllen RichardsonОценок пока нет

- Madina Books GlossaryДокумент256 страницMadina Books GlossaryMu IsОценок пока нет

- Kant-Metaphysical Foundations of Natural ScienceДокумент69 страницKant-Metaphysical Foundations of Natural SciencescribdballsОценок пока нет

- Mullin Daniel 201305 PHD ThesisДокумент365 страницMullin Daniel 201305 PHD ThesisfalsifikatorОценок пока нет

- Philosophy Now December 2016 2017Документ60 страницPhilosophy Now December 2016 2017falsifikator100% (3)

- Early Frankfurt SchoolДокумент10 страницEarly Frankfurt SchoolfalsifikatorОценок пока нет

- Humans Nature and EhticsДокумент7 страницHumans Nature and EhticsfalsifikatorОценок пока нет

- LORENZ B. PUNTEL, Truth, Sentential Non-Composiotionality, and OntologyДокумент40 страницLORENZ B. PUNTEL, Truth, Sentential Non-Composiotionality, and OntologyfalsifikatorОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Ypp Infonet SP Sample Test - Mcqs and Cris enДокумент5 страницYpp Infonet SP Sample Test - Mcqs and Cris enfrida100% (1)

- Nature of Organizational ChangeДокумент18 страницNature of Organizational ChangeRhenz Mahilum100% (1)

- Application Form AYCДокумент2 страницыApplication Form AYCtriutamiОценок пока нет

- The Neon Red Catalog: DisclaimerДокумент28 страницThe Neon Red Catalog: DisclaimerKarl Punu100% (2)

- Quality Control + Quality Assurance + Quality ImprovementДокумент34 страницыQuality Control + Quality Assurance + Quality ImprovementMasni-Azian Akiah96% (28)

- Jesus & The Samaritan WomanДокумент8 страницJesus & The Samaritan Womansondanghp100% (2)

- History of Travel and TourismДокумент28 страницHistory of Travel and TourismJM Tro100% (1)

- 25 Slow-Cooker Recipes by Gooseberry PatchДокумент26 страниц25 Slow-Cooker Recipes by Gooseberry PatchGooseberry Patch83% (18)

- Cracking Sales Management Code Client Case Study 72 82 PDFДокумент3 страницыCracking Sales Management Code Client Case Study 72 82 PDFSangamesh UmasankarОценок пока нет

- Engineering Forum 2023Документ19 страницEngineering Forum 2023Kgosi MorapediОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент2 страницыCase StudyMicaella GalanzaОценок пока нет

- Company Deck - SKVДокумент35 страницCompany Deck - SKVGurpreet SinghОценок пока нет

- Informal GroupsДокумент10 страницInformal GroupsAtashi AtashiОценок пока нет

- English Q3 Week 3 BДокумент3 страницыEnglish Q3 Week 3 BBeverly SisonОценок пока нет

- Fair Value Definition - NEW vs. OLD PDFДокумент3 страницыFair Value Definition - NEW vs. OLD PDFgdegirolamoОценок пока нет

- Armscor M200 Series Revolver Cal. 38 Spl. - User ManualДокумент12 страницArmscor M200 Series Revolver Cal. 38 Spl. - User ManualTaj Deluria100% (2)

- JENESYS 2019 Letter of UnderstandingДокумент2 страницыJENESYS 2019 Letter of UnderstandingJohn Carlo De GuzmanОценок пока нет

- Topics PamelaДокумент2 страницыTopics Pamelaalifertekin100% (2)

- PROJECT CYCLE STAGES AND MODELSДокумент41 страницаPROJECT CYCLE STAGES AND MODELSBishar MustafeОценок пока нет

- 40 Rabbana DuasДокумент3 страницы40 Rabbana DuasSean FreemanОценок пока нет

- NeqasДокумент2 страницыNeqasMa. Theresa Enrile100% (1)

- BPI Credit Corporation Vs Court of AppealsДокумент2 страницыBPI Credit Corporation Vs Court of AppealsMarilou Olaguir SañoОценок пока нет

- Relationship between extracurricular activities and student performanceДокумент16 страницRelationship between extracurricular activities and student performanceallan posoОценок пока нет

- JMM Promotion and Management vs Court of Appeals ruling on EIAC regulation validityДокумент6 страницJMM Promotion and Management vs Court of Appeals ruling on EIAC regulation validityGui EshОценок пока нет

- Marine Elevator Made in GermanyДокумент3 страницыMarine Elevator Made in Germanyizhar_332918515Оценок пока нет

- Discourses and Disserertations On Atonement and SacrificeДокумент556 страницDiscourses and Disserertations On Atonement and SacrificekysnarosОценок пока нет

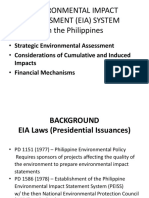

- Environmental Impact Assessment (Eia) System in The PhilippinesДокумент11 страницEnvironmental Impact Assessment (Eia) System in The PhilippinesthekeypadОценок пока нет

- Juris PDFДокумент4 страницыJuris PDFSister RislyОценок пока нет

- Single Entry System Practice ManualДокумент56 страницSingle Entry System Practice ManualNimesh GoyalОценок пока нет

- ArtmuseumstoexploreonlineДокумент1 страницаArtmuseumstoexploreonlineapi-275753499Оценок пока нет