Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nefrolitiasis 02

Загружено:

Steven SetioОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nefrolitiasis 02

Загружено:

Steven SetioАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Disease-a-Month

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/disamonth

Nephrolithiasis for the primary care physician

Judy Ann Tan, MD, Edgar V. Lerma, MD

Epidemiology

Renal and ureteral stones are a common problem in primary care practice. In the United

States, almost 2 million outpatient visits for a primary diagnosis of urolithiasis were recorded in

2000.1 The prevalence of kidney stones appears to be increasing in the United States. More

specically, a prevalence increase from 3.8% in the period 19761980 to 8.4% in the period from

2007 to 2010 has been documented by the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey.2

Up to 16% of men and 8% of women will have at least one symptomatic stone by the age of 70

years.3 The prevalence of nephrolithiasis increases with age is slightly higher in whites

compared with blacks, Asians, and Hispanics.2,3

Pathogenesis

Overall, 80% of patients with nephrolithiasis form calcium stones, most of which are

composed primarily of calcium oxalate or, less often, calcium phosphate.4 The other main types

include uric acid, struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate), and cystine stones (Fig. 1).

There are two prevailing theories regarding calcium stone formation. One theory is that stone

formation occurs as a result of supersaturation of the urine by stone-forming constituents,

including calcium, oxalate, and uric acid begins the process of crystal formation. It is presumed

that crystal aggregates become large enough to be anchored and then slowly increase in size

over time.

The second theory, which is most likely responsible for calcium stones, is that stone

formation is initiated in the renal medullary interstitium.5 Calcium phosphate crystals may form

in the interstitium and eventually get extruded at the renal papilla, forming the classic Randall's

plaque (which are always composed of calcium phosphate). Calcium oxalate or calcium

phosphate crystals may then deposit on top of this nidus, remaining attached to the papilla.

Risk factors

Environmental factors are presumably responsible for the increase in stone prevalence. For

example, stones are strongly associated with diabetes (especially for calcium and uric acid

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.disamonth.2015.08.004

0011-5029/& 2015 Mosby, Inc. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

J.A. Tan, E.V. Lerma / Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

435

Distribution of Stone Types

Calcium oxalate

Calcium oxalate and

calcium p hosphate

Calcium phosphate

Uric acid

Struvite

Fig. 1. Proportion of stone types in a typical U.S. population. (Adapted with permission from Comprehensive Clinical

Nephrology. 4th ed. 2010.)

stones), obesity, and the metabolic syndrome, which are, in parallel to stone prevalence,

increasing. A low-uid intake, with a subsequent low volume of urine production, produces high

concentrations of stone-forming solutes in the urine. This is an important, if not the most

important, environmental factor in kidney stone formation. High dietary salt, oxalate, and

protein have been implicated in altering urine composition to promote stone formation.

Low-dietary calcium content has been associated with the risk for stones, probably because

dietary calcium can precipitate intestinal oxalate and prevent its absorption from the intestine,

thus reducing oxalate excretion in the urine. Oxalobacter formigenes is an intestinal bacterium

that metabolizes oxalate. Colonization with Oxalobacter may reduce oxalate absorption from the

colon, reduce urinary oxalate, and protect against stones. Antibiotics may eliminate this

organism, thus increasing oxalate absorption from the intestine and oxalate excretion into the

urine.6 Chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections associated with high urine pH, particularly

with urease-producing organisms, such as Proteus species, are important predisposing factors

for struvite stones. Bowel disorders, such as inammatory bowel disease, and certain

gastrointestinal operations such as bariatric surgery and jejuno-ileal bypass are associated with

enteric hyperoxaluria and calcium oxalate stones.7 A number of medications or their metabolites

can precipitate in urine causing stone formation. These include indinavir, atazanavir,

acetazolamide, triamterene, sulfa drugs including sulfasalazine, sulfadiazine, and topiramate

(by increasing urine pH and decreasing citrate excretion) (Fig. 2).

Some genetic factors may likewise predispose a patient to develop kidney stones. More than

50% of patients in kidney stone clinics have a rst-degree relative with stones. Idiopathic

hypercalciuria is most likely a polygenic disorder; cystinuria is usually autosomal recessive; and

hyperuricosuria has been associated with rare inherited metabolic disorders.

Clinical manifestations

Majority of patients have ank pain that radiates downward and anteriorly into the abdomen

and then into the pelvis and genitals as stones progress down the ureter toward the

ureterovesical junction. The pain often starts suddenly and waxes and wanes. Nausea and

vomiting are oftentimes present. Gross or microhematuria may be observed. Stone passage is

associated with remarkable improvement or cessation of pain.

History and physical exam

The history should focus on establishing risk factors for stones, including family history of

kidney or ureteral stones, occupational status (certain occupations such as pilots and teachers

are associated with risk of kidney stones because of low-uid intake), diet, medications,

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

436

J.A. Tan, E.V. Lerma / Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

Hyperoxaluria

Dietary hyperoxaluria

High vitamin C

intake

Enteric oxaluria

Malabsorptive disorders

Sprue (celiac disease)

Crohns disease

Chronic pancreatitis

Jejuno-ileal bypass

Biliary obstruction

Primary hyperoxaluria

Hypocitraturia

Metabolic acidosis

Hypokalemia

Hypomagnesemia

Starvation

Infection

Androgens

Exercise

Hypercalciuria

Normal serum calcium

Idiopathic hypercalciuria

Elevated serum calcium

Malignancy

Primary

hyperparathyroidism

Granulomatous disease

(Sarcoidosis , tuberculosis)

Immobilization

Hyperthyroidism

Renal tubular

acidosis (type 1,

distal)

Nephrolithiasis

Fig. 2. Etiology of calcium stones. (Adapted with permission from Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology. 4th ed. 2010.)

supplements, and other medical conditions such as bowel diseases, hyperparathyroidism, and

malignancy. A history of other kidney or urologic conditions, such as urinary tract infection,

should be obtained.

The physical examination is most important for ruling out other conditions. Kidney and

ureteral stones have no specic manifestations on physical exam.

Clinical prediction rule created for estimating risk of kidney stones

Moore et al. derived and validated an objective clinical prediction rule for uncomplicated

ureteral stones that utilizes 5 patient factorssex, timing, origin (i.e., race), nausea, and

erythrocytes (STONE)to create a score between 0 and 13 (the STONE score). Patients with a

high STONE score are very likely to have a kidney stone and very unlikely to have an important

disorder other than a kidney stone as a cause of their symptoms.8

The factors most predictive of ureteral stones were male sex, short duration of pain, nonblack race, the presence of nausea or vomiting, and microscopic hematuria. In the derivation and

validation cohorts, ureteral stones were found in 8.3% and 9.2%, respectively, of low probability

(STONE score 05) patients, 51.6% and 51.3% of moderate probability (score 69) patients, and

89.6% and 88.6% of high probability (score 1013) patients.8

CT scans revealed acutely important alternative causes of symptoms on CT scan in 2.9% and 3.7%

of the derivation and validation cohorts overall. In the high score group, however, only 0.3% of the

derivation cohort and 1.6% of the validation cohort had acutely important alternative ndings.8

Differential diagnosis

Pyelonephritis may cause ank pain, but fever is expected. However, pyelonephritis and

stones sometimes coexist. Patients with conditions associated with peritonitis have fever,

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

J.A. Tan, E.V. Lerma / Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

437

abdominal tenderness, guarding, and rebound tenderness. In women, a pelvic examination may

suggest ovarian torsion, cysts, or ectopic pregnancy. In men, a rectal examination may identify

prostatic hypertrophy or prostatitis.

Imaging studies

Intravenous pyelogram (IVP) was previously the diagnostic procedure of choice in the

diagnosis of nephrolithiasis, but is no longer because of potential contrast reactions, lower

sensitivity, and higher radiation exposure.

Computed tomography (CT) is currently the gold standard for the diagnosis of renal colic.

It has superior sensitivity and specicity to IVP and ultrasonography. Calcium stones are radioopaque, cystine and struvite stones are often but not always radio-opaque, and uric acid stones

are never opaque unless they include a calcium component. Thus, non-calcium stones may be

missed by plain radiography but visualized by CT. CT is also better at making alternative

diagnoses when ureteral stones are not present. Because CT does not require contrast, it is faster

and safer than IVP.

While non-contrast CT scan has been suggested as the test of choice for most patients with

suspected nephrolithiasis, a recent study has shown that ultrasonography is an acceptable initial

imaging modality in patients with suspected nephrolithiasis who have a low clinical suspicion

for an alternative serious diagnosis.9 In a large multi-center trial, 2759 patients underwent

randomization to point-of-care ultrasonography, radiology ultrasonography, and CT for the

diagnosis of nephrolithiasis. Despite the lower sensitivity of ultrasonography, the rates of

important missed diagnoses that resulted in complications, such as pyelonephritis with sepsis or

diverticular abscess, were similar (0.5% with ultrasonography versus 0.3% with CT). Serious

adverse events and return visits to the ED after discharge were also similar. Patients assigned to

receive an initial CT were exposed to more than twice as much radiation during the initial ED

visit than those assigned ultrasonography.

Plain radiography of the abdomen is inexpensive, usually detects calcium stones 5 mm or

bigger, identies some non-stone diagnoses, and has a low dose of radiation.

Magnetic resonance imaging is a poor tool for visualizing stones.

Laboratory studies

All patients with recurrent nephrolithiasis warrant metabolic evaluation to determine the

etiology of their kidney stones. Comprehensive evaluation of patients with a rst stone is

controversial because of the undetermined cost-benet ratio. A National Institutes of Health

Consensus Development Conference on the Prevention and Treatment of Kidney Stones

recommends that all patients, even those with a single stone, should undergo a basic evaluation,

which need not include a 24-h urine collection.10 The European Association of Urology guidelines

corroborate these recommendations.11 The evaluation should include serum electrolytes, blood urea

nitrogen, creatinine, calcium, phosphorus, and uric acid. In patients with hypercalcemia, tests to

investigate the etiology of the metabolic imbalance such as parathyroid hormone level, 25-OH

vitamin D, 1,25 hydroxyvitamin D may be appropriate. A low-serum bicarbonate concentration with

a urine pH of 6.0 or more suggests renal tubular acidosis (RTA). Hypophosphatemia is seen in some

patients with a renal phosphate leak and calcium stones. High urine pH or pyuria should lead to

urine cultures and consideration of struvite stones.

Ancillary studies

More comprehensive analyses, such as 24-h urine collections for measurement of

chemistries, are usually reserved for patients with recurrent stones, children with stones, and

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

438

J.A. Tan, E.V. Lerma / Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

patients whose rst stones are larger and require surgical intervention. The 24-h urine collection

will aid physician to identify risk factors for recurrent stone formation that are then used to

prescribe specic diet and pharmacologic interventions. Patients should be advised to perform

the urine collection on a typical day while eating a typical diet.

Patients should be instructed to strain their urine to capture stones or fragments for analysis.

If a screen designed for the purpose capturing stones is not available, patients may be instructed

to urinate into a cup covered with a gauze pad.

Treatment

General treatment

Pain

Patients can be managed at home if they are able to take oral medications and uids.

A randomized trial suggested that NSAIDs and opioids may be superior to either agent alone.

Among 130 patients with renal colic, combination therapy with intravenous morphine (5 mg)

and ketorolac (15 mg) was associated with a greater reduction in pain at 40 min compared with

either agent alone.12

Fluid intake

An increase in urine volume to more than 2 L daily has been proven to reduce the incidence

of stones and is the mainstay of therapy for patients with kidney stones.13 Large urine volumes

will reduce calcium oxalate supersaturation as well as precipitation of other crystals. The period

of maximum risk for stone formation is at night, when urine concentration is physiologically

increased. Patients should thus be encouraged to drink enough uid in the evening.

Salt intake

Urine sodium excretion augments urine calcium excretion.14 Conversely, dietary salt

restriction is associated with a decrease in calcium excretion. Patients should thus be instructed

to limit daily sodium intake to 2 g.

Dietary calcium

Studies have demonstrated a decrease in stone incidence when people consume diets

adequate in calcium. This benecial effect has been attributed to the binding of dietary calcium

to ingested oxalate. It is therefore recommended that an age- and gender-appropriate calcium

diet is taken, although excessive dietary calcium intake and calcium supplements should be

avoided in patients with calcium nephrolithiasis.

Specic treatment for stone type

Calcium stones

For patients with hypercalciuria, the usual rst-line therapy is a thiazide diuretic, which

reduces urinary calcium. The 24-h urine calcium, sodium, and citrate excretion should be

rechecked after several weeks of initiating the medication. If the calcium excretion remains

elevated, the thiazide dose should be increased.

For patients with hyperoxaluria, treatment consist of dietary oxalate restriction. Calcium

carbonate (11.5 g) may be added at each meal and snack to bind intestinal oxalate and to

prevent its absorption.

Specic therapy for the malabsorptive disorder is the rst line of treatment of enteric

hyperoxaluria.

Citrate inhibits stone formation. A number of conditions reduce urinary citrate excretion,

predisposing to stone formation. Excessive protein intake, hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis,

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

J.A. Tan, E.V. Lerma / Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

439

exercise, hypomagnesemia, infections, androgens, starvation, and acetazolamide have all been

implicated in decreased urinary citrate excretion. Therapy involves treatment of the underlying

condition and potassium citrate supplementation.

Uric acid stones

Treatment of uric acid stones involves increasing urine volume and pH as well as decreasing

uric acid excretion. To raise urine pH, potassium citrate is recommended. Whereas sodium

bicarbonate alkalinizes the urine and enhances uric acid solubility, the added sodium may

increase sodium urate formation.

A low-purine and low-animal protein diet is also useful in raising urinary pH and decreasing

uric acid excretion. If uric acid excretion remains high despite dietary intervention, as in patients

with disorders of cellular catabolism, medications that inhibit uric acid formation such as

allopurinol should be prescribed.

Struvite stones

Struvite stones require aggressive medical and surgical management. Antibiotic therapy is

important to reduce further stone formation and growth. However, bacteria will remain in the

stone interstices, and stones will continue to grow unless chronic antibiotic suppression is

maintained or the calculi are completely eradicated. Given the need for complete stone removal

to affect a cure, early urologic intervention is advised.

Cystine stones

Treatment must be directed at decreasing the urinary cystine concentration below the limits

of solubility. Because the dietary precursor of cystine, methionine, is an essential amino acid, it is

impractical to reduce intake. Increasing urine volume so that cystine remains below the limits of

solubility sometimes requires 4 L of urine per day. A low-sodium diet has likewise been reported

to reduce urine cystine excretion.15

Hospitalization

Consider hospitalization for patients with stones larger than 5 mm, patients with nausea and

vomiting who are unable to tolerate oral medication and those requiring parenteral therapy to

manage pain.

A meta-analysis of 327 studies by the Ureteral Stones Clinical Guidelines Panel convened

by the American urologic association (AUA) found that 98% of smaller stones ( o 5 mm)

passed spontaneously. Distal ureteral stones passed more frequently than proximal ureteral

stones.16

An obstructed and infected urinary tract is an absolute indication for hospitalization and

emergent intervention, because this condition can result to urosepsis and irreversible renal

parenchymal damage. Admission is also required for patients with bilateral obstruction or

obstruction in a solitary kidney especially if decreased kidney function is evident.

Urology consultation

Urologic consultation is recommended for stones larger than 5 mm as the likelihood

of spontaneous passage of stones of this magnitude is low or when complications occur.

Urinary tract infection with obstruction is the most urgent indication for urologic

consultation.

Usually, urologists will decide whether a procedure will be performed and which procedure

will be undertaken. The choice often depends on the urologists assessment and skills and the

patients preference. The American Urology Associations (AUA) Ureteral Stones Clinical

Guidelines Panel and the European Association of Urology (EAU) recommend extracorporeal

shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) as rst-line treatment for stones no larger than 1 cm in diameter

in the proximal ureter; ureteroscopy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy are acceptable options,

especially if ESWL is inappropriate or fails.17 For stones larger than 1 cm in diameter in the

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

440

J.A. Tan, E.V. Lerma / Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

proximal ureter, percutaneous nephrolithotomy or ureteroscopy is recommended. For distal

ureteral stones, ESWL or ureteroscopy is advised; although for larger stones, ureteroscopy may

be more appropriate because ESWL must fragment stones into smaller pieces to be successful.

For patients with stones who are undergoing ESWL, subsequent treatment with alpha-blockers

such as tamsulosin should be considered to aid passage of stone fragments. The AUA

recommendations regarding the management of staghorn calculi suggest that percutaneous

nephrolithotomy should be the rst treatment used for most patients, and that ESWL

monotherapy should not be used for most patients.

Prognosis

Approximately 8085% of stones pass spontaneously.

The most morbid and potentially dangerous aspect of stone disease is the combination of

urinary tract obstruction and upper urinary tract infection. Pyelonephritis and urosepsis

can ensue.

The usually quoted recurrence rate for urinary calculi is approximately 15% at 1 year, 3540%

at 5 years, and 50% at 10 years, with men being more likely to recur than women.18 Later data

from randomized controlled trials have found slightly lower recurrence rates of approximately

5% per year for the rst 5 years.19

Asymptomatic nephrolithiasis

Nephrolithiasis is occasionally an incidental nding on imaging studies in patients who are

asymptomatic. There is a recognizable risk that a previously asymptomatic stone will become

symptomatic with expectant therapy. The likelihood of developing symptoms was approximately 32% at 2.5 years and 49% at 5 years.20 Expectant therapy may be a reasonable approach

in asymptomatic patients with small, non-infected calculi, without evidence of obstruction.

However, certain asymptomatic patients, depending upon their risk factors, occupation or comorbidities (e.g., solitary kidney) should undergo evaluation and treatment to reduce the risk of

recurrent stone formation or growth of existing stones.

Screening

No evidence supports the screening of patients for asymptomatic stones unless they have

recurrent stones unresponsive to usual therapy.

Key points

Diagnosis

(1) Patients with nephrolithiasis classically present with acute ank pain with nausea and/or

vomiting, with or without hematuria.

(2) History should include risk factors, including family history, underlying renal disease

contributing to stone formation (e.g., RTA), diet, medications, and medical and surgical comorbidities.

(3) Perform urinalysis to assess for concomitant infection; note that the absence of hematuria

does not rule out stone disease.

(4) Obtain helical CT or ultrasonography (in patients with suspected nephrolithiasis who have a

low clinical suspicion for an alternative serious diagnosis) to conrm the diagnosis of

nephrolithiasis.

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

J.A. Tan, E.V. Lerma / Disease-a-Month 61 (2015) 434441

441

Therapy

(1) NSAIDs, opiates, or both may be used to provide effective analgesia for acute renal colic.

(2) Urgent urologic intervention is warranted for stone removal in patients with infection,

uncontrollable pain, acute renal insufciency, or persistent obstruction.

(3) Attempt stone analysis in patients with a rst episode of nephrolithiasis and perform a

comprehensive evaluation, including 24-h urine examination, in those with recurrent

stones.

Prevention

(1) Recommend uid intake of at least 2 L/d in patients with personal or family history of kidney

stones, diseases associated with stone formation, or increased uid needs.

(2) Use thiazide diuretics to lower urinary calcium excretion in patients with hypercalciuria.

(3) For patients with recurrent calcium stones and hyperuricemia, recommend a diet that

minimizes animal proteins and salt, and optimizes calcium.

(4) Use allopurinol to prevent recurrent calcium oxalate stone formation in patients with high

uric acid excretion.

References

1. Pearle MS, Calhoun EA, Curhan GC, Urologic Diseases of America Project. Urologic diseases in America project:

urolithiasis. J Urol. 2005;173(3):848.

2. Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, Nyberg LM, Curhan GC. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in

the United States: 19761994. Kidney Int. 2003;63(5):1817.

3. Scales CD Jr, Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saigal CS, Urologic Diseases in America Project. Prevalence of kidney stones in the

United States. Eur Urol. 2012;62(1):160165. [Epub 2012 Mar 31].

4. Coe FL, Parks JH, Asplin JR. The pathogenesis and treatment of kidney stones. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(16):1141.

5. Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, et al. Randall's plaque of patients with nephrolithiasis begins in basement membranes

of thin loops of Henle. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):607.

6. Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Curhan GC, et al. Oxalobacter formigenes may reduce the risk of calcium oxalate kidney stones.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:11971203.

7. Lieske JC, Kumar R, Collazo-Clavell ML. Nephrolithiasis after bariatric surgery for obesity. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:

163173.

8. Moore CL, Bomann S, Daniels B, et al. Derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for uncomplicated

ureteral stonethe STONE score: retrospective and prospective observational cohort studies. Br Med J. 2014;348:

g2191.

9. Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected

nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep;371(12):11001110.

10. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on prevention and treatment of kidney stones.

Bethesda, Maryland, March 2830, 1988. J Urol. 1989;141:705808.

11. Tiselius HG, Ackermann D, Alken P, et al. Guidelines on urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 2001;40(4):362371.

12. Safdar B, Degutis LC, Landry K, et al. Intravenous morphine plus ketorolac is superior to either drug alone for

treatment of acute renal colic. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(2):173.

13. Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, et al. Urinary volume, water, and recurrences in idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis: a 5year randomized prospective study. J Urol. 1996;155(3):839843.

14. Lemann J Jr, Worcester EM, Gray RW. Hypercalciuria and stones (Finlayson colloquium on urolithiasis). Am J Kidney

Dis. 1991;17(4):386.

15. Goldfarb DS, Coe FL, Asplin JR. Urinary cystine excretion and capacity in patients with cystinuria. Kidney Int. 2006;69

(6):10411047.

16. Segura JW, Preminger GM, Assimos DG, et al. Ureteral stones clinical guidelines panel summary report on the

management of ureteral calculi. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997;158(5):19151921.

17. Preminger GM, Tiselius HG, Assimos DG, et al. 2007 guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. J Urol.

2007;178(6):24182434.

18. Uribarri J, Oh MS, Carroll HJ. The rst kidney stone. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(12):1006.

19. Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, Briganti A, Novarini A, Giannini A. Urinary volume, water and recurrences in idiopathic

calcium nephrolithiasis: a 5-year randomized prospective study. J Urol. 1996;155(3):839.

20. Glowacki LS, Beecroft ML, Cook RJ, Pahl D, Churchill DN. The natural history of asymptomatic urolithiasis. J Urol.

1992;147(2):319.

Downloaded from ClinicalKey.com at Universitas Tarumanagara December 13, 2016.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright 2016. Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Supplementary Table 1a. All Study Data For Bladder Cancer IncidenceДокумент19 страницSupplementary Table 1a. All Study Data For Bladder Cancer IncidenceSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- RCOG Cardiac Disease and Pregnancy PDFДокумент18 страницRCOG Cardiac Disease and Pregnancy PDFSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- Guidlines Pregnancy and Heart DiseaseДокумент52 страницыGuidlines Pregnancy and Heart DiseasePanggih Sekar Palupi IIОценок пока нет

- Nefrolitiasis RadiologiДокумент9 страницNefrolitiasis RadiologiSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- RCOG Cardiac Disease and Pregnancy PDFДокумент18 страницRCOG Cardiac Disease and Pregnancy PDFSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- Sle 05 PDFДокумент6 страницSle 05 PDFSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- Adrenal CrisisДокумент6 страницAdrenal CrisisSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- Fleis PDFДокумент1 страницаFleis PDFSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Gynecology and ObstetricsДокумент4 страницыInternational Journal of Gynecology and ObstetricsSteven SetioОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Muscle and Fitness Hers Features Elite Lifestyle Chef Carlo FilipponeДокумент4 страницыMuscle and Fitness Hers Features Elite Lifestyle Chef Carlo FilipponeCarlo FilipponeОценок пока нет

- Metabolism of Carbohydrates and LipidsДокумент7 страницMetabolism of Carbohydrates and LipidsKhazel CasimiroОценок пока нет

- Tiếng AnhДокумент250 страницTiếng AnhĐinh TrangОценок пока нет

- Facts About Concussion and Brain Injury: Where To Get HelpДокумент20 страницFacts About Concussion and Brain Injury: Where To Get HelpJess GracaОценок пока нет

- L Addison Diehl-IT Training ModelДокумент1 страницаL Addison Diehl-IT Training ModelL_Addison_DiehlОценок пока нет

- Active Contracts by Contract Number Excluded 0Документ186 страницActive Contracts by Contract Number Excluded 0JAGUAR GAMINGОценок пока нет

- TherabandДокумент1 страницаTherabandsuviacesoОценок пока нет

- DR K.M.NAIR - GEOSCIENTIST EXEMPLARДокумент4 страницыDR K.M.NAIR - GEOSCIENTIST EXEMPLARDrThrivikramji KythОценок пока нет

- Index Medicus PDFДокумент284 страницыIndex Medicus PDFVania Sitorus100% (1)

- Biomedical Admissions Test 4500/12: Section 2 Scientific Knowledge and ApplicationsДокумент20 страницBiomedical Admissions Test 4500/12: Section 2 Scientific Knowledge and Applicationshirajavaid246Оценок пока нет

- A V N 2 0 0 0 9 Airspace Management and Air Traffic Services Assignment 1Документ2 страницыA V N 2 0 0 0 9 Airspace Management and Air Traffic Services Assignment 1Tanzim Islam KhanОценок пока нет

- INTP Parents - 16personalitiesДокумент4 страницыINTP Parents - 16personalitiescelinelbОценок пока нет

- Frequency Inverter: User's ManualДокумент117 страницFrequency Inverter: User's ManualCristiano SilvaОценок пока нет

- Essay Type ExaminationДокумент11 страницEssay Type ExaminationValarmathi83% (6)

- Me N Mine Science X Ist TermДокумент101 страницаMe N Mine Science X Ist Termneelanshujain68% (19)

- NTJN, Full Conference Program - FINALДокумент60 страницNTJN, Full Conference Program - FINALtjprogramsОценок пока нет

- Rigging: GuideДокумент244 страницыRigging: Guideyusry72100% (11)

- Electric Field Summary NotesДокумент11 страницElectric Field Summary NotesVoyce Xavier PehОценок пока нет

- Brochure - ILLUCO Dermatoscope IDS-1100Документ2 страницыBrochure - ILLUCO Dermatoscope IDS-1100Ibnu MajahОценок пока нет

- 8 Categories of Lipids: FunctionsДокумент3 страницы8 Categories of Lipids: FunctionsCaryl Alvarado SilangОценок пока нет

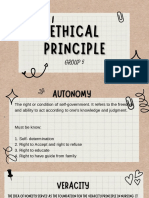

- Group 5 - Ethical PrinciplesДокумент11 страницGroup 5 - Ethical Principlesvirgo paigeОценок пока нет

- WeaknessesДокумент4 страницыWeaknessesshyamiliОценок пока нет

- Floret Fall Mini Course Dahlia Sources Updated 211012Документ3 страницыFloret Fall Mini Course Dahlia Sources Updated 211012Luthfian DaryonoОценок пока нет

- Removing Eyelid LesionsДокумент4 страницыRemoving Eyelid LesionsMohammad Abdullah BawtagОценок пока нет

- Variance AnalysisДокумент22 страницыVariance AnalysisFrederick GbliОценок пока нет

- NCR RepairДокумент4 страницыNCR RepairPanruti S SathiyavendhanОценок пока нет

- Free Higher Education Application Form 1st Semester, SY 2021-2022Документ1 страницаFree Higher Education Application Form 1st Semester, SY 2021-2022Wheng NaragОценок пока нет

- Earth Loop ImpedanceДокумент5 страницEarth Loop ImpedanceKaranjaОценок пока нет

- Safety Tips in Playing ArnisДокумент2 страницыSafety Tips in Playing ArnisDensyo De MensyoОценок пока нет

- Legg Calve Perthes Disease: SynonymsДокумент35 страницLegg Calve Perthes Disease: SynonymsAsad ChaudharyОценок пока нет