Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

A Survey of The Phases of Indian Ecocriticism

Загружено:

Jeet SinghОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A Survey of The Phases of Indian Ecocriticism

Загружено:

Jeet SinghАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture

ISSN 1481-4374

Purdue University Press Purdue University

Volume 16 (2014) Issue 4

Article 9

A SSur

urve

veyy of the PPhhases of IIndi

ndiaan EEco

cocr

crititic

iciism

Rayson K

K.. A

Alex

lex

Birla Institute of Technology and Science

Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb

Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons

Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and

distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business,

technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences.

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the

humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and

the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the

Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index

(Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the

International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is

affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact:

<clcweb@purdue.edu>

Recommended Citation

Alex, Rayson K. "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014):

<http://dx.doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2616>

This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field.

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu

http://www.thepress.purdue.edu>

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture

ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb

http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb>

Purdue University Press Purdue University

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture

Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access

access learned journal in the

the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative

literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." In addition to the

publication of articles, the journal publishes review articles of scholarly books and publishes research material in its

Library Series. Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and

Literature (Chadwyck-Healey),

Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation In

Index

dex (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities

Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern LanguaLangua

ge Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <

<clcweb@purdue.edu>

Volume 16 I

Issue 4 (December 2014) Article 9

Rayson K. Alex,

"A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

<http://docs.li

http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Contents of CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014)

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism

Ecocriticism.. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

<http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/

http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/>

Abstract: In his article "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism" Rayson K. Alex places Indian

ecocriticism

ism in its historical context distinguishing it from the Western ecocritical canon by identifying

and contextualizing three phases of ecocriticism in India

India. Looking at the

he present Indian ecocritical scesc

nario, Alex compares and contrasts

s it with Western ecocritical studies. He offers a brief analysis of the

themes of papers presented in conferences on ecocriticism in India and of the syllabi and teaching

strategies adopted in various institutions

nstitutions of higher learning which have introduced ecocriticism as opo

tional/mandatory courses to show

ow the growth of ecocriticism in India. Alex finds that present

ecocritical scholarship in India is largely influenced by Western ecocriticism

ecocriticism, although

though it originally began with the use of Indian theories and texts. Alex calls for a commitment to a regional approach

a

in

Indian ecocriticism and points to social issues that ecocriticism in India needs to address in the near

future: land, ethnicity, sustainability, poverty, terrorism, religious plurality, caste, water policies, and

education.

Rayson K. Alex, "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

page 2 of 8

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

Rayson K. ALEX

A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism

Lawrence Buell views the growth of ecocriticism in the West in two phases, "the first wave" and the

"second wave" ("Ecocriticism" 138). Practitioners ecocriticism's first wave focused on "romantic poetry

and American nature writing" (Moellering 6) and analyzed literary texts with regard to their mere personalized/experiential content which probably began with the publication of Jonathan Bate's Romantic

Ecology in 1991 and Buell's The Environmental Imagination in 1995 (see Garrard 360). The first wave

includes humanist, anthropocentric, biocentric, and ecocentric ideologies. The second wave saw a shift

of thrust from the rural to the urban and from nature to environment prompting the discipline to be

sociocentric. Bioregional, ecopolitical, and postcolonial theories were a vital part of this wave. In his

"Ecocriticism: Some Emerging Trends," Buell offers analyses of the European, British, US-American,

Japanese, Chinese, and Indian schools of ecocriticism to invite ecocritics' attention to the ecocritical

scope in so-called "third world" countries. I posit that it is in this context that Indian ecocriticism's history should be analyzed. The two objectives of this article are to analyze critically the past and present

areas of ecocritical/environmental engagements in Indian scholarship in the context of the large body

of ecocritical scholarship in the West and to express concerns for the future of Indian ecocriticism.

First, however, it is necessary to justify the soil metaphor used in the study at hand. Scott Slovic,

Swarnalatha Rangarajan, and Vidya Sarveswaran although they critique Buell's "wave" metaphor as

compartmentalizationuse the same framework to describe the future directions of ecocriticism in the

West in his "The Third Wave of Ecocriticism." My use of the soil metaphor is because it describes the

different layers of soil such as "rockbed," "regolith," "subsoil," and "topsoil" (see Zaffagnini, Becker,

Kerkhoffs, Espregueria Mendes, van Dijk 155). The list of layers is in descending order. Rockbed is the

base level soil and topsoil is the soil in the surface level of the earth. Nevertheless, the soil is a single

unit, although comprising of different layers which have distinct characteristics. The soil allows water

to permeate. Moreover, soil signifies permanence, base, life, and continuity. Thus instead of the metaphor of "wave," the soil metaphor suits my purpose better. However, the layers of soil should not be

seen as tight compartments but rather as porous and dynamic.

Nirmal Selvamony introduced in 1980 a course entitled "Tamil Poetics" at Madras Christian College

and this was the beginning of ecocriticism in India. Selvamony used translated Tamil texts as primary

sources for the course and the course drew heavily from his extensive eight-year Ph.D. research entitled Persona in Tolkappiyam. He had also published, with Nirmaldasan, three booklets entitled tinai 1,

tinai 2, and tinai 3 which gave ecocriticism in India a strong momentum. Selvamony renamed the

course "Ecoliterature" in 1996, following which the Department of English at Madras Christian College

organized the 3rd World Conference and the 11th All India English Teachers' Annual Conference in

2004, the first conference in India addressing environmental issues in literature. The objectives of the

conference were to strengthen the ecoliterature course, identify interested persons in the area, and initiate student community into the new discipline. Scott Slovic, editor of the journal ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment and who was the keynote speaker of the conference, initiated the idea of launching an Indian chapter of ASLE: Association for the Study of Literature and Environment India in an informal, small group, where Selvamony, Watson Solomon, Murali

Sivaramakrishnan, myself, and others were present. This was the evolutionary phase of ecocriticism in

India and I call this 1980-2004 phase of Indian ecocriticism the rockbed layer (the base layer).

The second phase 2004-2009, or the regolith of Indian ecocriticism, the propagatory period of

ecocriticism led to the formation of well-organized groups named OSLE: Organization for Studies in

Literature and Environment India in Chennai and its counterpart, ASLE India in Puducherry (now the

new name for Pondicherry). A few months after the world conference, Selvamony convened a meeting

of interested people in ecocriticism. The purpose of this meeting was to discuss the launch of

ecocriticism as a unified group, drawing an action plan to spread ecocriticism in India, and to encourage research. This would be achieved by organizing workshops and conferences; publishing newsletters, journals, and books; initiating the introduction of courses on ecocriticism at colleges and universities, and doing research projects. OSLE India became a registered body in 2005. Although organized

work on ecocriticism began with the formation of OSLE India, Selvamony and others wrote on

Rayson K. Alex, "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

page 3 of 8

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

ecocriticism, developed regional ecocritical concepts, and created ecopoetry from the 1980s onwards.

But the systematic work undertaken by OSLE India gave a sudden push to ecocriticism. Within nine

years, OSLE India had achieved much: seven national/international conferences; collaborations with

colleges on over five seminars; seventeen workshops in schools and colleges; thirty-five study circles;

two published book collectionsone entitled Essays in Ecocriticism (2007) and the other Culture and

Media: Ecocritical Explorations (2014)and three volumes of the Indian Journal of Ecocriticism; and

twelve online issues of the OSLE India Newsletter. It also extended ecocriticism to media through its

Ecomedia Team (a caucus group in OSLE India).

In the rockbed layer of Indian ecocriticism, although the term ecocriticism was not in currency,

there were many Tamil scholars working on tinai as a poetic convention in Tamil, as well as in English,

which was later identified as an ecocritical theory by Selvamony. tinai is a concept which includes the

cultural and artistic aspects of a particular land. Tolkappiyar, in his work Tolkappiyam (1000-600 BC)

first mentions the concept of tinai. tinai is not only a concept, but also the social order and poetic convention of the early Tamil people. The system still prevails in the tribal traditions of India (see

Selvamony, "An Alternative" 215). tinai combines the natural and cultural features of specific landscapes found in Tamil Nadu. The landscapes are divided into fivenamely, the montane (kurinci), the

pastoral (mullai), the desertic (paalai), the riverine (marutam), and the littoral (neytal). The landscapes are named after native flowers which are the keystone species in the specific landscapes (see

Selvamony, "An Alternative" 215-16). A.K Ramanujan's 1970 The Interior Landscape: Love Poems

from a Tamil Anthology and 1985 Poems of Love and War: From the Eight Anthologies and the Ten

Long Poems of Classical Tamil and some other texts are examples of the vast tinai scholarship in India

considering it as a poetical convention. There are a few other works which do not acknowledge the

term tinai, but actually describe the historical and political structures of the tinai Sangam Age. The

Sangam Age in Tamil history demarcates the major three groups of poets who wrote poetry, composed songs, and did extensive research on Tamil. The third group of poets wrote for over 400 years

which began sometime between 3rd century BC to 3rd century AD (see Britto). It was in this context

that Selvamony launched his course entitled "Tamil Poetics" at Madras Christian College in 1980. The

course objectives included that the students study Sangam poetry (in translation) through careful

analysis and understanding of the people, their lifestyle, occupation, socio-economic-politicaltheological structures, art forms, land/landscape, flora and fauna in the landscape, and the relationship with the land. The uniqueness of the course was that Selvamony saw tinai as not only a poetic

convention, but also as a social order which is inclusive of all artistic conventions (see "An Alternative"

215). Continuing this argument in its broader sense, Selvamony wrote on the cultural, social, theological, musicological, and ecological aspects of the five tinaikal (landscapes). His original theory

"oikopoetics," an extraction of tinai (integrative oikos [oikos means household]), is applicable to the

contemporary world (nonintegrative oikos): "being the habitat of the people concerned, oikos [tinai]

forms the matrix of all social institutionseconomy, polity, family and communication. Art, especially

poetry, is a variety of communication/communion shaped by the oikos of the society in question. Being the ground, matrix, and context of a work, oikos is the first principle of oikopoetics" (Selvamony,

"Oikopoetics" 1).

Selvamony mentions that oikopoetics is but "the oikos of the society" ("Oikopoetics" 1). Like tinai,

Oikopoetics is a sociocentric theory that belongs to the rockbed layer which is a part of the second

wave of ecocriticism identified by Buell. However, the sociocentrism thrust by Buell in the second wave

is not an idealized order of an ecological society; instead, it is an issue-based social engagement. In

contrast to Selvamony's commitment to a future ecosocial order, Buell's sociocentrism is of a contemporary social treatment that does not really get to the root of the problem. However, being

sociocentric, Selvamony's oikopoetics and tinai belong to Buell's second wave of ecocriticism. This is

the first phase of Indian ecocriticism and so remains in the rockbed layer. In the regolith layer of

ecocriticism in India (2004-2009), the organized and systematic team work opened avenues in the

academy to research, discourse, paper presentations, publications, field trips, syllabi creation, and

pedagogy. In nine years, OSLE India grew to over six hundred members from various parts of the

country. It is true that the engagements of OSLE India were extraordinarily effective in bringing together people under a single roof, but what was the scholarly content of the phase? I seek to answer

this question by analyzing the ecocritical discourse of the layer. I propose to survey two different kinds

Rayson K. Alex, "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

page 4 of 8

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

of texts to arrive at a conclusive answer, namely the abstracts of the seven national and international

conferences and the syllabi for ecocriticism across India.

The following section of the article surveys the abstract booklets of the conferences organized by

Madras Christian College, Central University of Tamil Nadu, the Birla Institute of Technology and Science, and OSLE India. The conferences were organized in collaboration with a number of educational

institutions and other bodies. Table 1 below presents an overview of the themes of the abstracts presented in the conferences excluding the abstracts of the non-Indian delegates.

Table 1: Papers presented at Ecocriticism conferences

year & theme

2004 International Conference on Contemporary Literatures in English: Theory & Practice with focus on

Environment & Literary Studies

2006 I International Conference of OSLE India

2007 II International Conference of OSLE India

2008 III International Conference of OSLE India

2010 The Name and Nature of Indian Ecocriticism

2012 Ecocritical Perspectives on Water

2014 Towards Ecocultural Ethics: Recent Trends and

Future Directions, Birla Institute of Technology and

Science

Total

# of papers

nature &

environment oriented

ecological &

concept

based

bio&ecocentric

sociocentric

36

27

25

11

68

75

52

51

82

164

62

67

44

37

42

78

6

8

8

14

7

14

55

60

32

45

23

37

13

15

20

6

10

35

528

357

66

277

110

The purpose of Table 1 is to categorize the papers thematically. The categorization of "natureoriented"/"ecological concept-based" and "bio/ecocentric"/"sociocentric" papers are not on a logical

basis and so do not distinguish clearly between the thematic categories in the Table. Of all the papers,

357 belong to the nature/environment-oriented category, which are anthropocentric. Selvamony

maintains that the environmental approach is not useful as "environment not only puts the human

subject it envelops in the center but also dichotomizes the relation between human and the environment." He condemns the term 'environment' as anthropocentric ("Introduction" xi). Only 12% of the

total number of papers have ecological content or have employed ecological concepts to analyze literary and cultural texts. Of the large number of individuals working in the area of "environment and literature," 67% are on the area of nature writing, environmental writing, nature criticism, and environmental criticism. The Indian academia during the 1980s to the early 2000s promoted ecological research and was involved in regional understandings of ecology. There were some ecofeminist studies

in the rockbed layer of ecocriticism and there was stress on the need for postcolonial ecocritical approaches. Overall, the organized movement of ecocriticism which began in 2004 witnessed a movement towards an ecocriticism that was decidedly Western. Scholars at the beginnings of ecocriticism in

India studied the socio-political-cultural-religious structures which influenced the ecological structure

of Indigenous communities. tinai and oikopoetics were theories which gave effective platforms for

such a local-centric ecocriticism.

Regionalism in the regolith layer was indistinct with ecocriticism in India imitating Western

ecocritical frameworks. Murali Sivaramakrishnan's 2008 Nature and Human Nature and

Sivaramakrishnan's and Ujjwal Jana's 2011 Ecological Criticism for Our Times: Literature, Nature and

Critical Inquiry are studies which center around the nature/environment category. Ecoambiguity,

Community, and Development: Toward a Politicized Ecocriticism (2014), edited by Scott Slovic,

Swarnalatha Rangarajan, and Vidya Sarveswaran, uses Karen L. Thornber's theory of "ecoambiguity"

from her 2012 book, Ecoambiguity: Environmental Crisis and East Asian Literatures as the framework

of the book. With two Indian ecocritics as editors and articles by Indian authors, the volume is a political statement about social issues communities and the cultures in the south face. However, the term

"ecoambiquity" is accepted uncritically failing to see that virtually everything can be discussed in

terms of ambivalence and ambiguity. Simon C. Estok makes precisely this point in his

problematization of the term "ecoambiguity," a term that in his reading is comparable to notions such

as "homoambiguity" and "gynoambiguity" (for homophobia and misogyny respectively), which as

Estok explains are suspect (see "Reading"). Ecocriticism in India in the regolith layer exists as an

Rayson K. Alex, "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

page 5 of 8

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

amalgamation of rockbed and regolith layers. Although there is permeation between these layers, the

characteristics of these layers are distinct and they exist in unity.

A discipline or theory acquires legitimacy when it is introduced as a course at institutions of higher

learning. The optional ecoliterature/ecopoetics courses for postgraduates at Madras Christian College,

Loyola College, Bishop Heber College, and Women's Christian College have similarities between their

pedagogical objectives and content. The prescribed texts are largely Western introducing the concepts

of deep ecology and bioregionalism. Regional concepts such as nativism, tinai, and oikopoetics are also included in the syllabi. The courses in these institutions and the ones in the Indian Institute of

Technology Madras and Pondicherry University follow a classroom-oriented pedagogy, whereas CUTN

and BITS Pilani and K.K. Birla Goa Campus have introduced a fieldwork-based pedagogy alongside

classroom teaching. Most of the courses on ecocriticism in these institutions have a component of ethnographic fieldwork in their syllabi. It is a sociocentric approach where the students are exposed to

different communities with different worldviews. This sociocentric ecocritical pedagogy is in the

rockbed layer of ecocriticism in India. The scope and challenge of ecocriticism in Indian educational institutions are yet to address local ecological issues. Such a pedagogy should address local-centric rather than Western-centric issues. At CUTN, regionalism in Indian ecocritical pedagogy became more

pronounced and I call this phase of Indian ecocriticism "subsoil." The three-semester ecocriticism

course at CUTN adopted a field-based study structure. In the third semester, the course takes a departure by introducing twenty-five compulsory hours of fieldwork of ecology-based projects in broad

areas including ecovideo-documentary, ecopoetry, ecoessay, and ecophotoessay. Students are exposed to an activity-based and constructivist pedagogy. Donna Haraway's concept of "situated

knowledge" which is culture-based and language-based, becomes location and local-based in this context: situated knowledges are locatable (location-oriented) and are claims with responsibility (583). A

candid conversation with my student stands testament to the effectiveness of the local-centric pedagogy. The conversation also evinces the responsibility that the student seems to have taken for himself/herself.

The one-semester optional course entitled "Ecocriticism" at BITS Pilani and K.K. Birla Goa Campus,

adopts a local-centric pedagogy. Students identify a local ecological issue from Goa, perform research

on it, problematize it, document it, and present it as a video documentary. Some of the students do

the documentary to complete the required evaluative module, some students show their passion towards the module that they try hard to use innovative cinematic techniques, engage in five to ten

days of field visits, and interview a number of people spending quality time and observing their activities and video-documenting them. The documentary project apart from the creation of a documentary

introduces ethnographic research to the students and equips the students to mull over the ethics involved in the process of research. The activity broadens the definition and scope of ecology to oral

narratives, cultural production such as rituals, myths and songs within the purview of ecologyplacing

humanities at the center of ecological discourse (see Slovic, "Felicitation" 2). One student (who wishes

to be anonymous), after completing his project on mining, shared his experience and thoughts thus:

"it was quite disturbing to listen to one of my informants that they are not comfortable, living in their

own ancestral home because her agricultural lands are now barren; they are filled with mining silt. Her

water-well is unusable as the ground water is polluted; her children are asthmatic and they are poor.

When I sit in my father's flat, thinking of the unique experience that I had with the villagers in

Colomb, what am I expected to think? Just think? Or do something? The question that took the front

seat while doing fieldwork is, why is the government doing this to the people? But now the problem is

within me. Don't they have the right to a peaceful and healthy home, as I have?"

Such thought-provoking feedback by a student gives immense joy to any instructor. However, the

response of the student made me think about the implicit outcomes of such projects. Although the

project turns out to be a documentary, the implicit effect of the work done is deep-seated. The student experienced a change in perspective (see Belyea 14) through the conflicts that he faced while doing the project. The first conflict is straightforward (referring to the first question that the student had)

and the second seems to be more profound and he is analytical of it (referring to the second question

that the student had). The second conflict becomes central to ecocriticism, as it addresses oikos. This

umbrella framework that Indian ecocriticism offers through the concept of tinai includes all the specific

issues ecocriticism would address, especially in the context of Western ecocriticism and other differ-

Rayson K. Alex, "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

page 6 of 8

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

ences. The framework of home is not static or a primal concept, but a dynamic one which provides a

platform for varied arguments and critiques. The strength of this framework is that however the definition of oikos changes, a home is a homenew or old, imagined or real, existent or non-existent,

Western or Eastern, on water, land or in the air.

The principle behind this field-based pedagogy is the understanding that land-based/oikos-based

social issues are primarily ecological. This should not be mistaken with the basic principle of social

ecology. While social ecologists would argue that all ecological issues occur due to human (societal)

interferences (see Bookchin), I suggest that social issues have ecological implications. The ecocriticism

course at BITS Pilani and K.K. Birla Goa Campus initiates a physical engagement with issues students

identify with. After evaluation the projects are uploaded on YouTube/Facebook by the instructor and

students and the screening and discussion of the films are arranged at the institute by the instructor.

The documentaries are then made available for public access. Two students' documentaries which are

available online for free access, are Colomb: The Land that Survived

(<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zXkcBjSG5Y>) and Shrigao: Residents' Perspectives on Mining (<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PdvXU1z0IaM>). One comment to the YouTube video entitled Colomb explains that "Filomena Dias shows a major breathing problem. She struggles for breath

in this video. This is an excellent awareness too" (Collaco

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zXkcBjSG5Y>). In the video, Filomena Dias, from the village of

Colomb, narrates about the status of her village after mining began there. The students' engagement

with the community using video obviously has far-reaching effects. Collaco, who watched the video,

comments that it is "an excellent awareness" (Collaco

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zXkcBjSG5Y>). I call this "digital ecoactivist pedagogy" (DEP),

a response to the dearth of activism in ecocriticism Estok describes in "Theorizing in a Space of Ambivalent Openness: Ecocriticism and Ecophobia." I see DEP as a pedagogical strategy in which the student engages in a particular ecological issue in a region (understanding or studying a group of people,

their socio-cultural-economic and ecological aspects in the place) using a digital medium. The scope of

DEP is many times more than a classroom-based (or a traditional fieldwork-based) study, since the

video document (a realistic product) remains online.

The expansion of the "digital ecoactivism" (using digital media in documenting the ecology/ecological issues in a geographical region) led to the initiation of a novel concept within ecocritical

scholarshipthe tinai Ecofilm Festival (TEFF)at BITS Pilani and K.K. Birla Goa Campus. Since

ecoactivism involves political and social engagement, digital ecoactivism calls for a participation in the

struggle for an ecological change through the conduit of digital media. The festival acts as a catalyst

to propagate digital ecoactivism. TEFF is the first film festival organized by an ecocritical forum in India and it aims to reach out to young ecoenthusiasts and ecofilmmakers by organizing film festivals at

various institutions in the country. TEFF also offers a unique space to share, discuss, and learn from

various ecological issues across the globe.

Ecocriticism in India now exists as a unit permeating the rockbed, regolith, and subsoil. Standing

at the threshold of the second wave of ecocriticism, Buell in The Future of Environmental Criticism argues that ecocriticism will grow in terms of "race, gender, sexuality, class and globalization" (129), in

its "reinterpretation of thematic configurations as pastoral, eco-apocalypticism" (130), and as a fieldbased pedagogy, involved in art, academics, and activism (132). Similar to Buell's ecocritical concerns

which are West-oriented, Indian ecocritics need to address issues specific to India. In his

"Ecocriticism: Emerging Trends" Buell envisions a "collaborative project" (107) towards a transnational

ecocriticism. Serenella Iovino in her "The Human Alien: Otherness, Humanism, and the Future of

Ecocriticism" brings to the fore a similar concern by stressing the insurgence of "'a diversity of voices'

contributing to the understanding of the human relationship to the planet" (53). Buell and Iovino anticipate comparative global ecocriticism that would globalize specific ecocultural issues of cultural

communities. What should an Indian ecocritic engage in in the present Indian ecocritical context? I

envision the topsoil layer in Indian ecocriticism should address socio-cultural issues that lack

ecohumanities' engagements in Indiaethnography, ethnicity, regionalism, nationalism, water and

land issues, media and films, social order/systems, poverty, international politics, terrorism, religious

plurality, the system of caste, natural resources policies, security and educational system. Whether the

topsoil Indian ecocriticism will address these issues in the near future or never in future is not very

Rayson K. Alex, "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

page 7 of 8

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

important, but as the eighth principle of deep ecology reminds human beings of their responsibility, if

at all humans identify this as their responsibility, frequent interactions between theory and praxis

could be anticipated.

Ecocriticism in India is expanding far and wide as the following Table 2 shows:

Table 2: An overview of the Phases in Indian Ecocriticism

Phases

Timeline

Characteristics of the Phases

The Rockbed Layer

1980-2004

The Regolith Layer

2004-2009

The Subsoil Layer

2009-present

tinai-oriented ecocritical work; Focus on Tamil and

English literary texts; Focus on indigeneity in

ecocriticism

Teamwork through OSLE India and ASLE India;

Regular OSLE India meetings and study circles in

which people attended from different parts of the

country; Chennai-based but participation of members from East, West and North of India; Imitation

of Western ecocriticism; Increased analysis of English, Australian, US-American and Canadian literary

texts; Emergence of analysis of Sanskritic texts from

an ecocritical perspective; Strengthening of Western

influence; tinai attains global acceptance

Focus on tinai, cinema and cultural texts; Production

of ecocritical documentaries; Media documents in

ecocritical pedagogy

In conclusion, although ecocriticism in India began in the south of India (Tamil Nadu), it has

spread far and wide with the personal engagements of ecocritics in India and in an organized manner

through OSLE India and ASLE India. Although some of the activities are not organized consistently,

OSLE India organizes conferences, seminars, workshops, and the tinai Ecofilm Festival. Both organizations are involved in publishing books, encourage research, and engage in major and minor ecoliterary

and ecocultural projects. Indian scholars use Western theoretical frameworks and Western literary

texts in doing ecocriticism, they also employ regional concepts (Dravidian, Buddhist, and Sanskritic) in

order to analyze Indian classical, modern, and postmodern literary texts and Indigenous narratives,

films, documentaries, and cultural documents as texts to understand ecological implications of people

and communities. Indian ecocritical scholarship, although influenced by Western scholarship, needs to

keep its identity as Indian, thereby contributing to global ecocriticism. This can be better achieved

with what I call an "econativistic" ("Econativism" 290), an ecoregional movement.

Note: The above article is a revised version of Alex, Rayson K. "A Critical Call for the Second Wave in Indian

Ecocriticism," Contemporary Contemplations on Ecoliterature. Ed. Suresh Frederick. New Delhi: Authorspress,

2012. 1-14. Copyright release to the author. I thank Simon C. Estok who gave me an impetus to rethink my earlier

"A Critical Call for the Second Wave in Indian Ecocriticism" and S. Susan Deborah for comments and suggesting the

metaphor of soil. I also thank Meenakshi Raman (Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani) for her support

and encouragement.

Works Cited

Aditya, Santosh Y., P. Vishnuvardhan, S. Anish, K. Harikishan, and T. Abhiram. Colomb: The Land that Survived.

(2014): <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zXkcBjSG5Y>.

Alex, Rayson K. "Econativism in Select Poems of Joy Harjo." Contemporary Contemplations on American Literature.

Ed. Suresh Frederick. New Delhi: Authorspress, 2014. 290-306.

Bate, Jonathan. Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition. London: Routledge, 1991.

Belyea, Andrew, and Nanette Norris. "Introduction: Ecocritical Spring and Evolutionary Discourse." Words for a

Small Planet: Ecocritical Views. Ed. Nanette Norris. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2013. 1-16.

Bookchin, Murray. "What is Social Ecology?" Anarchy Archives (2001):

<http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bookchin/socecol.html>.

Britto, John S. "Ancient Historical Perceptions on Cheras from Sangam Classical Literature." Indian Historical Studies 10.1 (2013): 1-20.

Buell, Lawrence. "Ecocriticism: Some Emerging Trends." Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences 19.2

(2011): 87-115.

Buell, Lawrence. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture.

Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1995.

Buell, Lawrence. The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination. Malden:

Blackwell, 2005.

Collaco, Bevinda. Colomb Final Cut (2014): <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zXkcBjSG5Y>.

Rayson K. Alex, "A Survey of the Phases of Indian Ecocriticism"

page 8 of 8

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.4 (2014): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol16/iss4/9>

Thematic Issue New Work in Ecocriticism. Ed. Simon C. Estok and Murali Sivaramakrishnan

Estok, Simon C. "Reading Ecoambiquity: Review Essay on Karen Laura Thornber's Ecoambiguity: Environmental

Crises and East Asian Literatures." Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature, Culture, and Environment 4.1

(2013): 130-38.

Estok, Simon C. "Theorizing in a Space of Ambivalent Openness: Ecocriticism and Ecophobia." ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 16.2 (2009): 203-25.

Garrard, Greg. "Ecocriticism and Education for Sustainability." Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 7.3 (2007): 360.

Gruenewald, David A. "The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place." Environmental Education Research

14.3 (2008): 308-24.

Iovino, Serenella. "The Human Alien: Otherness, Humanism, and the Future of Ecocriticism." Ecozon@: European

Journal of Literature, Culture, and Environment 1.1 (2010): 53-61.

Haraway, Donna. "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective." Feminist Studies 14.3 (1988): 575-99.

Moellering, Kurt A.R. William Wordsworth, Henry David Thoreau, and the construction of the Green Atlantic World.

Ph.D. Diss. Boston: Northeaster U, 2010.

Ramanujan, A.K. The Interior Landscape: Love Poems from a Classical Tamil Anthology. London: Peter Owen,

1970.

Ramanujan, A.K., and Tolka ppiyar. Poems of Love and War: From the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems

of Classical Tamil. New York: Columbia UP, 1985.

Rueckert, William. "Literature and Ecology: An Experiment in Ecocriticism." The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in

Literary Ecology. Ed. Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm. Athens: U of Georgia, 1996. 105-23.

Selvamony, Nirmal. "An Alternative Social Order." Value Education Today: Explorations in Social Ethics. Ed. J.T.K.

Daniel and Nirmal Selvamony. Madras: Madras Christian College, 1990. 215-36.

Selvamony, Nirmal. "Introduction." Essays in Ecocriticism. Ed. Nirmal Selvamony, Nirmaldasan, and Rayson K.

Alex. New Delhi: Sarup and Sons, 2007. xi-xxxi.

Selvamony, Nirmal. Persona in Tolkappiyam. Ph.D. Diss. Madras: Indian Institute of Tamil Studies, 1998.

Selvamony, Nirmal, and Nirmaldasan. tinai 1. Chennai: Persons for Alternative Social Order, 2001.

Selvamony, Nirmal, and Nirmaldasan. tinai 2. Chennai: Persons for Alternative Social Order, 2002.

Selvamony, Nirmal, and Nirmaldasan. tinai 3. Chennai: Persons for Alternative Social Order, 2003.

Sharma, Ankit, Karthik Sundaram, Rahul Sharma, and Vivek Solanki. Shrigao: Residents Perspectives on Mining

(2014): <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PdvXU1z0IaM>.

Sivaramakrishnan, Murali, and Ujjwal Jana, eds. Ecological Criticism for Our Times: Literature, Nature and Critical

Inquiry. New Delhi: Authorspress, 2011.

Sivaramakrishnan, Murali, ed. Nature and Human Nature: Literature, Ecology, Meaning. Delhi: Prestige, 2008.

Slovic, Scott, Swarnalatha Rangarajan, and Vidya Sarveswaran, eds. Ecoambiguity, Community, and Development:

Toward a Politicized Ecocriticism. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2014.

Slovic, Scott. "Felicitation." Abstract Book of International Conference on Towards Ecocultural Ethics: Recent

Trends and Future Directions. Goa: BITS Pilani, 2014. 2.

Thornber, Karen L. Ecoambiguity: Environmental Crises and East Asian Literatures. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P,

2012.

Zaffagnini, Stefano, Roland Becker, Gino M.M.J. Kerkhoffs, Joao Espregueria Mendes, and C. Niek van Dijk, eds.

Esska Instructional Course Lecture Book: Amsterdam 2014. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.

Author's profile: Rayson K. Alex teaches ecocriticism, cinematic arts, and aesthetics at the Birla Institute of Technology and Science. His interests in scholarship include eco-indigeneity and ecocinema. In addition to numerous articles, his book publications include the collected volume Essays in Ecocriticism (2007) and Culture and Media:

Ecocritical Explorations (2014). His recent documentary is entitled Thorny Land: Invasion of Cheemakaruvel

(2014). Alex is also founder and co-director of the tinai Ecofilm Festival. E-mail: <raysonalex@goa.bitspilani.ac.in>

Вам также может понравиться

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 1От EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 1Nina MirnigОценок пока нет

- Cargoes in Motion: Materiality and Connectivity across the Indian OceanОт EverandCargoes in Motion: Materiality and Connectivity across the Indian OceanОценок пока нет

- Postcolonial Studies in The Twenty-First Century - A Book Review AДокумент8 страницPostcolonial Studies in The Twenty-First Century - A Book Review ADavid EinsteinОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Cultural Text Analysis and Liksoms Short StoryДокумент6 страницIntroduction To Cultural Text Analysis and Liksoms Short Storymarsjanix0% (1)

- Comparative Literature in IndiaДокумент10 страницComparative Literature in IndiaMaheshwari JahanviОценок пока нет

- Cultural Studies and Cultural Text AnalysisДокумент8 страницCultural Studies and Cultural Text Analysistaraj.lahdha.blahdhaОценок пока нет

- Bibliography For Work in EcocriticismДокумент10 страницBibliography For Work in Ecocriticismdvm1010Оценок пока нет

- ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©purdue University: Volume 17 (2015) Issue 1 Article 4Документ9 страницISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©purdue University: Volume 17 (2015) Issue 1 Article 4WhITe GaRОценок пока нет

- Bibliography For Work in Holocaust Studies PDFДокумент59 страницBibliography For Work in Holocaust Studies PDFJohn Philipp KroisОценок пока нет

- Clcweb: Comparative Literature and Culture Clcweb: Comparative Literature and CultureДокумент10 страницClcweb: Comparative Literature and Culture Clcweb: Comparative Literature and CultureDELOS SANTOS, APRIL JOY E.Оценок пока нет

- Cultural Studies and Cultural Text AnalysisДокумент9 страницCultural Studies and Cultural Text AnalysisbudisanОценок пока нет

- Towards A History of Intertextuality in Literary and Culture StudДокумент10 страницTowards A History of Intertextuality in Literary and Culture StudangielskiajОценок пока нет

- César Domínguez - Literary Geography and Comparative LiteratureДокумент8 страницCésar Domínguez - Literary Geography and Comparative LiteraturePedroОценок пока нет

- Literature and EnvironmentДокумент24 страницыLiterature and EnvironmentsohamgaikwadОценок пока нет

- Werner Wolf (Inter) Mediality and The Study of LiteratureДокумент10 страницWerner Wolf (Inter) Mediality and The Study of LiteratureCaro Maranguello100% (1)

- From Commonwealth To Postcolonial LiteratureДокумент8 страницFrom Commonwealth To Postcolonial Literaturecatrinel_049330Оценок пока нет

- Concepts of World Literature Comparative Literature and A PropoДокумент9 страницConcepts of World Literature Comparative Literature and A PropoLaura Rejón LópezОценок пока нет

- Cultural Studies and Cultural Text Analysis: Clcweb - Comparative Literature and Culture December 2002Документ9 страницCultural Studies and Cultural Text Analysis: Clcweb - Comparative Literature and Culture December 2002Madalena van ZellerОценок пока нет

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4От EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4Lucas den BoerОценок пока нет

- Ecocriticism and Persian and Greek Myths About The Origin of FireДокумент9 страницEcocriticism and Persian and Greek Myths About The Origin of FireXander ClockОценок пока нет

- Download Transformations Of A Genre A Literary History Of The Beguiled Apprentice Ralph Cohen all chapterДокумент67 страницDownload Transformations Of A Genre A Literary History Of The Beguiled Apprentice Ralph Cohen all chapterjohnna.martin254100% (2)

- Bil 414 PDFДокумент4 страницыBil 414 PDFJuste SegueОценок пока нет

- Comparative Literature in India - Amiya DevДокумент8 страницComparative Literature in India - Amiya DevmazumdarsОценок пока нет

- Subject/Bibliography Guide: Literature in English: - 1 Holly StiegelДокумент10 страницSubject/Bibliography Guide: Literature in English: - 1 Holly Stiegelapi-87988746Оценок пока нет

- Edward Said PDF BiblioДокумент15 страницEdward Said PDF BiblioMushera Talafha67% (3)

- Post-Colonialism and Indian CultureДокумент8 страницPost-Colonialism and Indian Culturebadminton12Оценок пока нет

- Reaccessing Abhinavagupta - Navjivan RastogiДокумент15 страницReaccessing Abhinavagupta - Navjivan Rastogikashmir_shaivismОценок пока нет

- 04 Chapter1Документ9 страниц04 Chapter1Ahtesham AliОценок пока нет

- ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©purdue University: Volume 13 (2011) Issue 5 Article 4Документ9 страницISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©purdue University: Volume 13 (2011) Issue 5 Article 4GM YasОценок пока нет

- 2457 2452 1 PBДокумент31 страница2457 2452 1 PBcekrikОценок пока нет

- Bloom The Essay Canon 1999Документ31 страницаBloom The Essay Canon 1999Waves CurrentsОценок пока нет

- Alkindipublisher1982,+paper+44+ (2019 2 6) +Formalist+Criticism+Critique+on+Reynaldo+A +Duque's+Selected+Ilokano+PoemsДокумент54 страницыAlkindipublisher1982,+paper+44+ (2019 2 6) +Formalist+Criticism+Critique+on+Reynaldo+A +Duque's+Selected+Ilokano+PoemsRalph June CastroОценок пока нет

- Evolutionary Origins of US Nautre WritingДокумент16 страницEvolutionary Origins of US Nautre WritingGuillermo Guadarrama MendozaОценок пока нет

- Scriere Academica 2Документ14 страницScriere Academica 2AtraОценок пока нет

- On Reading Graces PotikiДокумент11 страницOn Reading Graces PotikiMylena QueirozОценок пока нет

- The Third Wave of Ecocriticism - Ecozon@Документ7 страницThe Third Wave of Ecocriticism - Ecozon@Daria FisenkoОценок пока нет

- A Concise Dictionary of Indian PhilosophyДокумент400 страницA Concise Dictionary of Indian PhilosophyEl Zorro100% (2)

- Comparative Literature and The Culture of The ContextДокумент12 страницComparative Literature and The Culture of The ContextparadoyleytraОценок пока нет

- Revisiting Seventeen - Year Literature (1949-1966) in China FromДокумент13 страницRevisiting Seventeen - Year Literature (1949-1966) in China FromalextruculenttelevisionОценок пока нет

- Download The Ocean Of Inquiry Niscaldas And The Premodern Origins Of Modern Hinduism South Asia Research Michael S Allen full chapterДокумент67 страницDownload The Ocean Of Inquiry Niscaldas And The Premodern Origins Of Modern Hinduism South Asia Research Michael S Allen full chaptercharles.grubbs815100% (2)

- Research Paper On EcocriticismДокумент19 страницResearch Paper On EcocriticismErwin PurciaОценок пока нет

- A Study On Translation of Chinese Children's Literature From The Perspective of Polysystem TheoryДокумент5 страницA Study On Translation of Chinese Children's Literature From The Perspective of Polysystem TheoryIJELS Research JournalОценок пока нет

- On Comparative Literature: November 2015Документ9 страницOn Comparative Literature: November 2015Fulvidor Galté OñateОценок пока нет

- Literatures of the World Lecture Series 2015Документ2 страницыLiteratures of the World Lecture Series 2015Bini SajilОценок пока нет

- Sem Iiapproachestolit - CriticismДокумент125 страницSem Iiapproachestolit - CriticismAkhil SethiОценок пока нет

- The Comparative Method and The Study of LiteratureДокумент5 страницThe Comparative Method and The Study of LiteratureZeeshan AhmedОценок пока нет

- Birth of Environmental Literary StudiesДокумент3 страницыBirth of Environmental Literary Studiesexam purposeОценок пока нет

- Medieval Literature: Chaucer to MaloryДокумент72 страницыMedieval Literature: Chaucer to Maloryआई सी एस इंस्टीट्यूटОценок пока нет

- SlovicThe-Fourth-Wave-of-Ecocriticism.docДокумент6 страницSlovicThe-Fourth-Wave-of-Ecocriticism.docFiОценок пока нет

- Dash - The Story of EconophysicsДокумент223 страницыDash - The Story of EconophysicsEricОценок пока нет

- Comparative - Literature With CoverДокумент17 страницComparative - Literature With CoverTamirat HabtamuОценок пока нет

- On Comparative LiteratureДокумент9 страницOn Comparative LiteratureMay IsettaОценок пока нет

- Banuazizi 1990 Reviewof Encyclopaedia IranicaДокумент6 страницBanuazizi 1990 Reviewof Encyclopaedia IranicasorinproiecteОценок пока нет

- Make Literature ReviewДокумент10 страницMake Literature ReviewPau Jane Ortega ConsulОценок пока нет

- Ecocriticism (Mid)Документ2 страницыEcocriticism (Mid)Saif Ur RahmanОценок пока нет

- Scope of Kosambist Paradigm in Kerala Historiography DISSERTATION by Shafeek HДокумент95 страницScope of Kosambist Paradigm in Kerala Historiography DISSERTATION by Shafeek HDivya D VОценок пока нет

- Philology in Manuscript CultureДокумент11 страницPhilology in Manuscript Culturecarlosandrescuestas100% (1)

- 70 13 Wint 24 1Документ24 страницы70 13 Wint 24 1CarlosAlbertoAponteEncaladaОценок пока нет

- Aristotle's Theory of Imitation ExplainedДокумент12 страницAristotle's Theory of Imitation ExplainedThlanthlá Peuleu100% (1)

- Allegorical or Symbolic Meaning of The PoemДокумент3 страницыAllegorical or Symbolic Meaning of The PoemJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Faculty of Social Sciences: Department of Journalism and Mass Communication B.A. SyllabusДокумент13 страницFaculty of Social Sciences: Department of Journalism and Mass Communication B.A. SyllabusJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Reification in Revolution 2020Документ10 страницReification in Revolution 2020Jeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Vultures Poem Explores Coexistence of Love and EvilДокумент1 страницаVultures Poem Explores Coexistence of Love and EvilJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Beyond Eschatological ConcernsДокумент50 страницBeyond Eschatological ConcernsJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Violence Against Women and Its Impact On Ecology A Postjungianperspective 2471 2701 1000S2 002Документ4 страницыViolence Against Women and Its Impact On Ecology A Postjungianperspective 2471 2701 1000S2 002Jeet SinghОценок пока нет

- The Question of Female Embodiment and Sexual Agency in Anuradha Sharma Pujari's KanchanДокумент7 страницThe Question of Female Embodiment and Sexual Agency in Anuradha Sharma Pujari's KanchanJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Violence Against Women and Its Impact On Ecology A Postjungianperspective 2471 2701 1000S2 002Документ4 страницыViolence Against Women and Its Impact On Ecology A Postjungianperspective 2471 2701 1000S2 002Jeet SinghОценок пока нет

- A Brief History of PsychoanalysisДокумент26 страницA Brief History of PsychoanalysisJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Post-colonial and Theoretical Aspects in Gurdial Singh's The Last FlickerДокумент28 страницPost-colonial and Theoretical Aspects in Gurdial Singh's The Last FlickerJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- The Goethean Concept of World Literature and Comparative LiteratuДокумент9 страницThe Goethean Concept of World Literature and Comparative LiteratuJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Dalit LiteratureДокумент4 страницыDalit LiteratureJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Siddhartha Gigoo's "The Umbrella ManДокумент4 страницыSiddhartha Gigoo's "The Umbrella ManJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- A Brief History of PsychoanalysisДокумент26 страницA Brief History of PsychoanalysisJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- EJES Trauma and Memory in the 21st CenturyДокумент10 страницEJES Trauma and Memory in the 21st CenturyJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Amended Rule 51 RevisedДокумент7 страницAmended Rule 51 RevisedJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Allegorical or Symbolic Meaning of The PoemДокумент3 страницыAllegorical or Symbolic Meaning of The PoemJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- MarxismДокумент1 страницаMarxismJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- The Ecocriticism Reader IntroductionДокумент16 страницThe Ecocriticism Reader IntroductionJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Politics of Aesthetics Intern at ional Journal of Applied Research 20 15; 1(13): 367-370Документ4 страницыPolitics of Aesthetics Intern at ional Journal of Applied Research 20 15; 1(13): 367-370Jeet SinghОценок пока нет

- THE ROAD AND HUMANISMДокумент6 страницTHE ROAD AND HUMANISMJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Amended Rule 51 RevisedДокумент7 страницAmended Rule 51 RevisedJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Work Load Guidelines & Standards For Faculty MembersДокумент6 страницWork Load Guidelines & Standards For Faculty MembersJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Daniele Monticelli CVДокумент14 страницDaniele Monticelli CVJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Course Study HandbookДокумент61 страницаCourse Study HandbookCharles BrittoОценок пока нет

- Syl Sydney ENVSTUA9510 ENGL-UA9TBA GiigsHamilton Spring2014Документ20 страницSyl Sydney ENVSTUA9510 ENGL-UA9TBA GiigsHamilton Spring2014Jeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Course Study HandbookДокумент61 страницаCourse Study HandbookCharles BrittoОценок пока нет

- Vikram Seth 2012 8Документ0 страницVikram Seth 2012 8Anasuya ChakrabartyОценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент295 страницPDFJeet SinghОценок пока нет

- APPSC Assistant Forest Officer Walking Test NotificationДокумент1 страницаAPPSC Assistant Forest Officer Walking Test NotificationsekkharОценок пока нет

- Pervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire DalmynДокумент5 страницPervertible Practices: Playing Anthropology in BDSM - Claire Dalmynyorku_anthro_confОценок пока нет

- PAASCU Lesson PlanДокумент2 страницыPAASCU Lesson PlanAnonymous On831wJKlsОценок пока нет

- Character Interview AnalysisДокумент2 страницыCharacter Interview AnalysisKarla CoralОценок пока нет

- Chapter 8, Problem 7PДокумент2 страницыChapter 8, Problem 7Pmahdi najafzadehОценок пока нет

- Entrepreneurship and Small Business ManagementДокумент29 страницEntrepreneurship and Small Business Managementji min100% (1)

- Intel It Aligning It With Business Goals PaperДокумент12 страницIntel It Aligning It With Business Goals PaperwlewisfОценок пока нет

- Discover books online with Google Book SearchДокумент278 страницDiscover books online with Google Book Searchazizan4545Оценок пока нет

- Lifting Plan FormatДокумент2 страницыLifting Plan FormatmdmuzafferazamОценок пока нет

- Executive Support SystemДокумент12 страницExecutive Support SystemSachin Kumar Bassi100% (2)

- Miss Daydreame1Документ1 страницаMiss Daydreame1Mary Joy AlbandiaОценок пока нет

- Sadhu or ShaitaanДокумент3 страницыSadhu or ShaitaanVipul RathodОценок пока нет

- New U. 4. 2Документ6 страницNew U. 4. 2Jerald Sagaya NathanОценок пока нет

- 2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanДокумент10 страниц2-Library - IJLSR - Information - SumanTJPRC PublicationsОценок пока нет

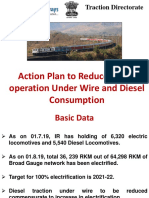

- Final DSL Under Wire - FinalДокумент44 страницыFinal DSL Under Wire - Finalelect trsОценок пока нет

- FOL Predicate LogicДокумент23 страницыFOL Predicate LogicDaniel Bido RasaОценок пока нет

- Risc and Cisc: Computer ArchitectureДокумент17 страницRisc and Cisc: Computer Architecturedress dressОценок пока нет

- Das MarterkapitalДокумент22 страницыDas MarterkapitalMatthew Shen GoodmanОценок пока нет

- Specification Table - Stocks and ETF CFDsДокумент53 страницыSpecification Table - Stocks and ETF CFDsHouse GardenОценок пока нет

- Transportation ProblemДокумент12 страницTransportation ProblemSourav SahaОценок пока нет

- Summer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterДокумент6 страницSummer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterRedwood Coast Land ConservancyОценок пока нет

- 01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsДокумент11 страниц01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsEnrique BlancoОценок пока нет

- Social Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaДокумент7 страницSocial Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaVlog With BongОценок пока нет

- Marikina Polytechnic College Graduate School Scientific Discourse AnalysisДокумент3 страницыMarikina Polytechnic College Graduate School Scientific Discourse AnalysisMaestro Motovlog100% (1)

- History Project Reforms of Lord William Bentinck: Submitted By: Under The Guidelines ofДокумент22 страницыHistory Project Reforms of Lord William Bentinck: Submitted By: Under The Guidelines ofshavyОценок пока нет

- Helical Antennas: Circularly Polarized, High Gain and Simple to FabricateДокумент17 страницHelical Antennas: Circularly Polarized, High Gain and Simple to FabricatePrasanth KumarОценок пока нет

- Komoiboros Inggoris-KadazandusunДокумент140 страницKomoiboros Inggoris-KadazandusunJ Alex Gintang33% (6)

- Disability Election ManifestoДокумент2 страницыDisability Election ManifestoDisability Rights AllianceОценок пока нет

- Group Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementДокумент3 страницыGroup Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementnoylupОценок пока нет

- 3 People v. Caritativo 256 SCRA 1 PDFДокумент6 страниц3 People v. Caritativo 256 SCRA 1 PDFChescaSeñeresОценок пока нет