Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Art of Motivating Behavior Change

Загружено:

Orban Csaba DanielИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Art of Motivating Behavior Change

Загружено:

Orban Csaba DanielАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Public Health Nursing Vol. 18 No. 3, pp.

178185

0737-1209/01/$15.00

Blackwell Science, Inc.

The Art of Motivating Behavior

Change: The Use of

Motivational Interviewing to

Promote Health

Harold E. Shinitzky, Psy.D., and

Joan Kub, Ph.D., R.N., C.S.

Abstract Health promotion and disease prevention have always

been essential to public health nursing. With the changing health

care system and an increased emphasis on cost-containment, the

role of the nurse is expanding even more into this arena. A

challenge for public health nurses, then, is to motivate and facilitate health behavior change in working with individuals, families,

and communities and designing programs based on theory. Leading causes of death continue to relate to health behaviors that

require change. The purpose of this article is to integrate theory

with practice by describing the Transtheoretical Model of Change

as well as the principles of motivational interviewing that can

be used in motivating behavioral change. A case scenario is

presented to illustrate the use of the models with effective interviewing skills that can be used to enhance health. Implications for

practice with an emphasis on providing an individually tailored

matched intervention is stressed.

Key words: Transtheoretical Model, motivational interviewing, health promotion, health behavior.

Harold E. Shinitzky is an Instructor, Department of Pediatrics,

Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Joan Kub is an Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland.

Address correspondence to Harold E. Shinitzky, 2531 Landmark Dr., Suite 203, Clearwater, FL 33761. E-mail: hshinitz@

jhmi.edu

178

INTRODUCTION

With the changing health care system and an increased

emphasis on cost-containment, the role of the nurse is

expanding more and more into the arena of health promotion. In 1986, the First International Conference on Health

Promotion was held in Ottawa, Canada. This conference

has served as a source of inspiration for health promotion

since that time. Five levels of action were outlined: (1)

building health public policy, (2) creating supportive environments, (3) strengthening community action, (4) developing personal skills, and (5) reorienting the health system

(World Health Organization [WHO], Health and Welfare

Canada, and the Canadian Public Health Association,

1986). It is increasingly recognized that action on all of

these levels is necessary for a comprehensive approach to

health. Influences on health occur at several levels including individual, interpersonal, community, environmental,

and health care system (Donatelle & Davis, 1998).

Health promotion strategies, which influence an individual or population, may be either active or passive. Passive

strategies involve the client as an inactive participant and

include approaches such as maintaining clean water. Active

strategies on the other hand, depend on the individual

becoming personally involved in adopting a proposed program of health promotion that might include exercise regimens or decreasing daily calories (Edelman & Mandle,

1998). Personal health behavior began to attract attention

in the 1960s, with the release of the First Surgeon Generals

Report on Smoking and Health. Since that time other areas

of human behavior, such as dietary patterns and physical

activity, have been subjects of major Surgeon Generals

Reports (Lee & Estes, 1997).

Shinitzky and Kub: Motivating Behavior Change 179

As outlined in the Ottawa Charter, we seek to explore

the role that nurses can play in promoting and developing

personal skills leading to healthier clinical outcomes. This

is not to negate the importance of the other skills, but it

is increasingly recognized that behavioral determinants of

health are contributing factors of premature death. These

leading causes of death in order of priority are tobacco,

diet and activity, alcohol, microbial agents, toxic agents,

firearms, sexual behavior, motor vehicles, and the illicit

use of drugs (McGinnis & Foege, 1993).

A challenge for public health nurses then, is to motivate

and facilitate health behavior change. Effective interpersonal skills are essential techniques that can be used to

accomplish this task. Enhancing the interpersonal communication skills of health providers results in increased levels

of satisfaction among clients and providers, greater adherence to treatment regimens, fewer lawsuits, continuity of

the same provider, and better follow-up on appointment

keeping (Hall, Roter, & Tand, 1988; Levinson, Roter, Mullooly, Dull, & Frankel, 1997; Wissow et al., 1998; Haynes,

1976).

Noneffective encounters often result in barriers to optimal care. Although most patients are able to identify approximately three to four issues that they would like to

address with their health care provider, one study revealed

that the average health care provider interrupts his or her

patients disclosures after 18 seconds (Beckman & Frankel,

1984). Post visit research has also revealed that 30 to

60% of medical information discussed in an encounter is

forgotten, and 50% of medical treatment regimens are not

followed to their fullest extent (Haynes, Taylor, & Sackett,

1981).

Our role as effective health care providers must include

then, an understanding of the interpersonal skills that can

be used to motivate individuals to move towards optimal

health. The purpose of this article is to integrate theory

with practice by describing one model, the Transtheoretical

Model of Change, that can guide nurses in facilitating

change and to further discuss principles of motivational

interviewing that can be used in facilitating this change.

Transtheoretical Model of Change

The Transtheoretical Model of Change, which consists of

five stages, has emerged from the research efforts of Carlo

DiClemente and James Prochaska over the past 18 years.

Most of the research has focused on smoking cessation,

but the model has also been applied to other addictive

behaviors including drug abuse, obesity, eating disorders,

gambling, exercise, and condom use (DiClemente & Prochaska, 1998). In the model, intentional behavior change

is emphasized as opposed to societal, developmental, or

imposed change (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcrass,

1992). The three organizing constructs of the model are

stages of change, processes of change, and levels of change

(DiClemente & Prochaska, 1998).

Stages of Change

The stages of change consist of five categories along a

continuum that reflect an individuals interest and motivation to alter a current behavior. It is through movement

along these stages that one is able to achieve successful

behavioral change (DiClemente & Prochaska, 1998). These

stages include precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Each health care provider

must determine the readiness to change or the stage in

which each patient is in prior to developing a treatment

plan.

1. Precontemplation is the stage in which there is an

unwillingness to change a problem behavior or there is

a lack of recognition of the problem. If a patient is not

thinking about any behavior change in the next 6

months, she or he is classified as a precontemplator.

2. Contemplation involves the stage in which there is a

consideration of change with a decision-making evaluation of the pros and cons of both the problem behavior

and the change. Individuals frequently begin to weigh

the consequences of action or inaction. At this point,

patients are able to discuss the negatives as well as the

benefits associated with the at-risk behavior. This opens

the door to a collaborative process. Usually, these patients discuss actually changing their current behavior

within a 6-month period.

3. Preparation represents the period when there is a commitment to change in the near future, usually 1-month.

Patients express a high degree of motivation towards

the desired behaviors and outcomes. Patients in the

preparation stage have determined that the adverse costs

of maintaining their current behavior exceed the benefits. Therefore, initiating a new behavior is more likely.

These patients have moved from thinking about the

issue to doing something about it.

4. The fourth stage, Action, is when change or modification of behavior actually takes place.

5. After 3 to 6 months of success, the last stage of Maintenance is begun. During this stage, there is a focus on

lifestyle modification in order to avoid relapse and to

stabilize the behavior change (Cassidy, 1997; DiClemente & Prochaska, 1998).

Processes of Change

The processes of change facilitate movement through the

stages of change. There are 10 processes that have been

identified that are responsible for movement (DiClemente & Prochaska, 1998). Five of these processes, which

include consciousness raising, dramatic relief, environ-

180 Public Health Nursing

Volume 18 Number 3 May/June 2001

mental reevaluation, social liberation, and self reevaluation,

are experiential or cognitive processes. These are internally

mediated factors that are associated with an individuals

emotions, values, and cognitions (Cassidy, 1997). Consciousness raising is described as encouraging individuals

to increase their level of awareness, seek new information,

or to gain an understanding about a problem. Dramatic

relief is experiencing and expressing feelings about ones

problems. Environmental reevaluation is assessing how

ones problem affects the physical environment. Social

liberation is increasing alternatives for nonproblem behaviors in society. Self reevaluation is assessing how one feels

and thinks about oneself in relationship to the problem

(Prochaska et al., 1992).

The five other processes (counter conditioning, helping

relationships, reinforcement management, stimulus control, and self-liberation) are behavioral processes (Prochaska et al., 1992; Cassidy, 1997). Counter conditioning

is substituting alternatives for problem behaviors. An example might be the use of meditation to cope with unpleasant emotions (Cassidy, 1997). Helping relationships are

defined as those that provide trust, acceptance, and support.

The provider that listens when there is a need to discuss

the problem is an example of this process. Reinforcement

management is the use of positive reinforcements and appropriate goal setting with the patient. Stimulus control is

helping the patient to restructure the environment so that

the stimuli or triggers for the undesired behavior are controlled. Self-liberation is when an individual believes in

him or herself and his or her ability to change.

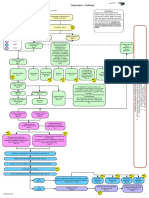

An integration of these processes with the stages can be

seen in Figure 1. In other words, there is a match between

the stage that the patient is in and the intervention that is

used. Individuals in the contemplation stage would be most

open to consciousness raising, the use of dramatic relief,

and an environmental reevaluation. In the action phase,

effective use of the behavioral processes is particularly

Figure 1. Stages of change in which processes are most emphasized. Reprinted with permission from Prochaska, Redding, &

Evers, 1997.

helpful (Prochaska et al., 1992); (Prochaska & DiClemente,

1983).

Levels of Change

Clinicians recognize that individuals have multiple problems that often overlap. Addiction, for example, may be associated with marital problems, financial problems,

personality disorders, depression, and violence. With this

recognition, the Transtheoretical Model of Change incorporates five levels of change for consideration. These include

changes that relate to the symptoms or situations, maladaptive cognitions, interpersonal problems, family/systems

problems, and intrapersonal conflicts. Treatment outcomes

are often better when a patients multiple problems are addressed (DiClemente & Scott, 1997). Understanding the life

context of our patients increases the probability that treatment plans will fit their overall needs and be individually

tailored. If we enter into this relationship with the belief

that we are to assess, diagnose, and treat only the most

obvious issue, we are likely to overlook other important

issues. If we remain open to the multiple factors impacting

our patients lives, however, we are apt to be inclusive

rather than exclusive of potential issues.

Research Findings

Support for the Transtheoretical Model of Change has been

accumulating over the past 15 years (DiClemente & Prochaska, 1998). Assessment of the stage of change that a

person is in is one of the most relevant findings for practice.

Previous research on estimating stage distribution has

found that typically 40% of a population with an unhealthy

behavior would be categorized in the precontemplation

stage, 40% would fall in the contemplation stage, and

20% would self-assess in the preparation stage (Dijkstra,

DeVries, & Bakker, 1996; Fava, Velicer, & Prochaska,

1995). Several studies have focused on creating assessment

tools to determine the level of motivation for change which

include the 12-item Readiness to Change measure (Rollnick, Heather, Gold, & Hall, 1992), the 20-item Alcohol

Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale (DiClemente, Carbonari,

Montgomery, & Hughes, 1993), the University of Rhode

Island Change Assessment (URICA) (McConnaughy,

DiClemente, Prochaska, & Velicer, 1989), the Stages of

Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) (Miller & Tonigan, 1996), and the Readiness Ruler

(DNofrio, Bernstein, & Rollnick, 1996).

Action oriented interventions often target the 20% of

the individuals in the preparation stage while the remaining

needs of the entire population are not being met. It would

therefore be incumbent to develop programs and interventions that either match the needs of individuals who have

not yet made the conscious effort to change or for health

Shinitzky and Kub: Motivating Behavior Change 181

care providers to assist in moving those at-risk individuals

along the continuum from precontemplation to action. Prochaska and Velicer (1997) found that stage-matched programs can assist 80 to 90% of an at-risk population of

smokers. These authors also found that 40% of the individuals who prematurely terminated treatment were initially

assessed as falling into the precontemplation stage.

Another important finding is that extensive relapse and

recycling occurs in populations attempting to take action

to change behavior. This appears to be the norm and has

important implications for practice. Terms such as noncompliant and unmotivated are frequent labels applied

to patients who do not follow through on their treatment

plans. This may reflect the norm of relapse or may also

reflect a poorly created treatment plan that does not consider the stage of change the patient is in. In labeling

patients as such, the provider may be externalizing responsibility, placing blame rather than reflecting upon his or

her own skills. Therefore appreciating the stage of change

the patient is in is imperative before we can begin to

develop an optimal treatment plan. Assessing the patients

position facilitates the development of an individually tailored and matched protocol.

Though our review of the Transtheoretical Model of

Change has focused on its application to an individual

patient, in actuality we may apply the model to families,

populations, and organizations. Prior to implementing an

intervention, one must assess and determine the readiness

to change. After determining the stage of readiness for that

group or individual, the intervention may be tailored to

match their position. By doing so, we can increase the

impact and effectiveness of our intervention.

MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

Once a patients stage of change is identified, the health

care practitioner needs to implement clinical skills that

will help facilitate the patients progression and movement

along the continuum. Motivational interviewing is a framework developed by Miller and Rollnick (1991) that can

help to facilitate this movement. It builds on the foundation

of understanding that our role as the health care provider

is to assist our patients to move toward a state of action

that leads to improved health status outcomes. A mutually

agreed upon treatment plan that is acceptable to the patient

and fits within the medical parameters is more likely to

be attained. Motivational interviewing is comprised of two

equally important phases, which include: Phase I

building a therapeutic rapport and commitment, and Phase

IIfacilitating the movement through decisional analysis

and behavior change. Table 1 outlines the principles of

motivational interviewing.

Motivational interviewing is a process that is based on

TABLE 1. The Five General Principles of Motivational

Interviewing (Miller, 1983)

1. Express empathy

a. Acceptance and understanding facilitates change

b. Skillful reflective listening is fundamental

c. Ambivalence is normal

2. Develop discrepancies

a. Awareness of consequences is important

b. Engage in a discussion between present behavior and

valued goals

c. Client driven rational for change

3. Avoid argumentation

a. Arguments are counterproductive

b. Judging (why?) breeds defensiveness

c. Resistance is a signal to change therapeutic strategies

d. Labeling is unnecessary

4. Roll with resistance

a. New perceptions are invited but not imposed

b. Client is a valuable resource re: solutions

c. Collaboration is valued

d. Mutually negotiated solutions

5. Support self-efficacy

a. Hope is motivating

b. Patient is responsible for choosing and initiating

c. There is hope in the range of alternatives

d. Knowledge that certain behaviors lead to desired outcomes

e. Possession of those behavior

input by both parties. A starting point is to establish a safe

environment in which our patients and their families feel

as though they can reveal personal information.

The art of motivational interviewing is therefore a dance

between two individuals suspending judgment and avoiding

a confrontational style thereby minimizing defensive reactions by the patient. Providers need to challenge patients

without eliciting defensiveness. When a patient reacts defensively, many providers tend to negatively label the patient

and accuse him or her of being noncompliant and resistant.

We view this as a logical behavioral reaction on the part

of the patient who may not perceive the issues in the same

manner. Providers need to be cautioned then, about challenging a patient too early and creating a dynamic relationship

that requires a defensive posture. As all behaviors are purposeful, we must understand what it is that our patient values

by maintaining his or her current unhealthy lifestyle behavior (for example, smoking).

Acceptance of the person does not mean agreement with

his or her behavior, but rather an appreciation of his or

her perceived issues. We need to be more open to and

understanding of our patients life contexts. It is best to

start out with the patients agenda. No patient comes to us

without some emotional concern. The emotional concern

is frequently the motivating factor that prompted him or

182 Public Health Nursing

Volume 18 Number 3 May/June 2001

her to schedule an appointment and seek out an experts

opinion. A competent provider acknowledges the emotional components of the encounter. To avoid addressing

these issues is a sign that the providers agenda is controlling the encounter.

Another important role of the provider is to help our

patients see that they are in control of their lives. The sense

of an internal locus of control, self-efficacy, and personal

empowerment leads to taking a more active role in ones

life (Egan, 1998). The patient is ultimately the one responsible for making behavioral changes in his or her life.

When mutually discussing treatment options and alternatives, it is important to brainstorm. During the brainstorming phase, cast the net as wide as possible. Subsequent

to identifying the vast array of possibilities, we then narrow

our options to the most viable alternatives. A key concept

during the brainstorming phase is to suspend judging the

best therapeutic fit. Criticizing forestalls creativity and

identification of all possibilities. Patients moving along the

continuum of change, need their providers to amplify the

discrepancy between the pros and cons which make up

their decision-making equation. During the encounter it is

important to refrain from lecturing, for pontificating the

right way only alienates our patients.

As providers we need to weigh our words wisely. Every

question asked needs to have some underlying purpose.

We need to be reflective of our style and of the line of

questioning. Whenever possible, providers need to avoid

habitually asking the question, why? (Benjamin, 1987).

This connotes disapproval and forces the patient to respond

with excuses or alibis. Asking open-ended questions is a

technique that encourages the patient to elaborate while

habitually using closed-ended questions leads to brief responses (that is, Yes or No). By utilizing these techniques

and skills, the encounter can be more rewarding. Recall that

each session must address the needs, concerns, and opinions

of the patient. Lastly, emotional factors are dealt with and

problem solving is mutually managed. Common problems

that providers can encounter are seen in Table 2.

CASE SCENARIO

The following case scenario depicts a patient in the different phases of the Transtheoretical Model of Change. Different motivational interviewing approaches, some less

effective and colleagues more effective, are presented to

illustrate the value of applying appropriately matched techniques to help patients progress towards change. It is your

task to determine the stage of change that this patient

currently fits and assess the encounter. The case scenario

that we present is based on a synthesis of actual patient

encounters.

Mr. Smith is a 46-year-old, African American male.

TABLE 2. Common Problems That Providers Display

1. Asking closed-ended questions. These do not foster an open

dialogue between the patient and the provider. They usually

limit the discussion to a yes or a no response.

2. Double options. Providers frequently assert an either-or

scenario. This implies that there are only two options and that

the provider is the one who knows which options are best.

This style does not empower the patient to take an active role

in problem solving.

3. Not responding to the emotional needs of a patient. Many

providers feel comfortable focusing on the bio-medical needs.

If a therapeutic rapport is not established, however, the patient

is likely to remain focused on their underlying emotional

issues that interfere with the effective flow of information

and negotiation.

4. Using cliches to respond to patient disclosures. If used too

often, they are perceived as trite and minimizing to the

patients.

He presents with an upper respiratory infection (that is,

wheezing, cough, and expectorant for 4 weeks). He has

smoked for 25 years. He is 5 8, 185 pounds, and has an

unremarkable medical history. He has a positive family

history for lung cancer in father and paternal grandfather.

He requested some prescribed antibiotics to resolve his

infection.

Nurse M: Mr. Smith, from what you have told me about your

symptoms, what do think might have contributed to your

infection?

Rationale: Respecting and valuing the patient as the

expert in his own life is an important skill. This question

is posed as an open-ended question, which allows the patient to elaborate from his perspective. This question also

assesses the level of knowledge and insight the patient

has regarding his current condition as well as initiates an

evaluation of his location regarding potential behavioral

changes.

Mr. S: I really dont know. I just need an order for some meds.

Rationale: Patient appears to be unaware or potentially

resistant and therefore, Precontemplative.

Nurse M: Based on the length of time of your symptoms, I

believe that your smoking cigarettes adds to your condition. You

should stop smoking.

Rationale: The provider has made a summarizing comment, however, this comment is latent with judgment and

confrontation. In essence, the provider is attempting to

force the patient from precontemplation into the action

stage. This provider was talking at, rather than with the

patient. The statement of obviously is filled with

judgment. The provider asserts the Gold Standards, yet

Shinitzky and Kub: Motivating Behavior Change 183

does not engage this patient in the problem-solving

opportunities.

Mr. S: Well, you know, I guess there wouldnt be any harm in

that.

Mr. S: No, I dont think so. I have been smoking cigarettes for

several decades and I have never had this before.

Rationale: By not directly challenging, the patient is

more accepting along the continuum. The patient is willing

to be reflective and accept educational information. We see

the movement from precontemplation to contemplation.

To further illustrate the movement along the continuum,

we shall continue with this patient encounter. Once a patient

is in the contemplative stage, our goal is to assist his

or her positive, healthy progression towards behavioral

change.

Rationale: The patient responds with resistance to the

confrontation. Denial is not a symptom of the addiction,

rather it is a defensive response to the providers accusation.

From the responses of this patient (that is, lack of insight or awareness of behavior problem and resistance)

we can determine that he falls within the category,

precontemplation.

Encounter Analysis: If this provider dictates the medical

treatment requirements without understanding and appreciating his or her patients life context, the patient will likely

fail and be labeled as noncompliant. Now that the provider

knows that once you have determined the correct stage of

change, however, the goal is to facilitate movement to the

next stage (Precontemplative to Contemplative). This is

best accomplished by matching motivational interviewing

techniques. Let us continue with Mr. Smith.

Nurse M: Mr. Smith, from the symptoms that you have expressed

and your history, I wonder if your smoking adds to this condition?

You might want to think about the potential impact of smoking

cigarettes has on your overall health.

Rationale: Again, using the history that the patient has

provided, active listening, and summarizing key points

back to the patient, the nurse displays genuine interest in

what has been said. This response also displays an active

listening style and the use of an indirect question. This

free-floating style continues the assessment of motivation

and insight into the patients condition. By offering numerous suggestions without any declarative accusations, the

provider is using the process of consciousness raising.

Mr. S: I never gave much thought to that. I know my family and

home has been affected by cigarette smoking and perhaps I have

too.

Rationale: Patient is willing to consider this as a point

of reflection due to the nonjudgmental style of the provider.

The patient also reveals a potential consequence associated

with the at-risk behaviors. Therefore, this patient has

shifted to the contemplation stage. The nurse has helped

the patient to use the processes of environmental reevaluation and self-liberation.

Nurse M: Would you care if I provided you with some information

for you to look over?

Rationale: Here the provider is establishing a partnership with this patient. Based on what he has said before,

we know that he had not considered this as contributing

to the problem. Engaging in option development without

imposing a judgment is vital.

Nurse M: Mr. S, from what you have told me about your symptoms, what do you think might have contributed to your infection?

Rationale: Asking an open-ended question facilitates

the encounter. This question elicits the patients opinions.

Again, we present this in a respectful manner that values

the patients observations and is therefore inclusive for

solutions.

Mr. S: Well, we have talked about how my smoking may be

making my infection worse and maybe even affecting my general

health.

Rationale: The patient used the word we, indicating

a mutual discussion rather than lecture from the provider.

Additionally, the patient states the possible connection between this behavior and adverse consequences. This individual appears to be in the contemplation stage.

Nurse M: Youve smoked for a couple of decades, what do you

find that you get from smoking?

Rationale: Since all behavior is purposeful, we need

to understand the reinforcing factors associated with this

behavior in order to adequately address this patients needs.

This is helping the patient to do a self-reevaluation.

Mr. S: I smoke when I am with my friends and it helps me to

relax.

Rationale: The patient openly discusses the rewards for

his current unhealthy behavior. These are needed when

seeking leverage and when increasing the discrepancy between the pros and cons.

Nurse M: I see. And what are the drawbacks?

Rationale: Determining the patients level of insight

and now assessing the negatives that will facilitate the

decision-making process.

Mr. S: Well, we both know that its not doing me any good

healthwise and it costs a lot.

Rationale: Mr. S is able to discuss both sides of the

equation. He openly discusses the negative consequences

associated with the at-risk behaviors. Again, these shall be

184 Public Health Nursing

Volume 18 Number 3 May/June 2001

used to accentuate the discrepancy between reinforcing

agents and contraindicators from the patients point of view.

Nurse M: It sounds like there are a few reasons that keep you

smoking and a few on the downside. There is a lot of evidence

that indicates cigarette smoking contributes to upper respiratory

problems and knowing your family history places you at further

risk for problems. If you were to see yourself in 6 months, what

would you be doing differently and how would you go about

getting there?

Rationale: This provider paraphrases the relevant history using the patients words. An indicator of the contemplation stage is the motivation to change behavior over the

next 6 months.

Mr. S: Well, I have tried to quit in the past. I guess I could try

to cut back. I would hopefully feel better than I do now.

Rationale: This patient affirms his willingness to problem solve by altering his at-risk behavior. This patient is

expressing the emotional struggle associated with changing

behaviors. Knowing that 50% of all medical treatment

plans are not followed through to their fullest extent, this

provider expresses an appreciation for the patients identified issue and attempts to partner with the patient to develop

a mutually agreed option.

Nurse M: That certainly sounds reasonable. Why dont you give

that a try. What do you think you could change over the next

month?

Rationale: Empathy and support. Rather than focusing

on the negatives, this provider has chosen to begin by

establishing a therapeutic rapport through reinforcing a

positive. The provider is determining if this patient is in

the preparation stage by inquiring if the behavior change

will occur within 1 month.

Mr. S: I can think about what we have talked about and start

making a game plan for changing my behavior. I guess I could

have fewer cigarettes.

Rationale: This patient has progressed to the preparation

stage by displaying motivation and a plan to alter his

behavior within the coming month.

Nurse M: Is there anything I can do to help you reach this goal?

Rationale: Always survey for more information or concerns. This displays your level of commitment and involvement and prevents those dreaded, Oh, by the way

comments as you and your patient are leaving the office.

Mr. S: Well besides standing next to me every moment, can you

tell me about some of those new treatment programs that I have

heard about?

Rationale: This response displays an active listening

style to the patient. As this patient has already declared a

potential contributing behavior, we then pose an indirect

question. We have moved this patient further along the

continuum through empathetic listening, enhancing the discrepancies, nonjudgmental problem solving, and empowering the patient. This free-floating style continues the

assessment of motivation and insight into his condition.

The provider refrained from labeling or presenting this

in an accusatory manner. The provider is now using the

behavioral processes in the Transtheoretical Model of

Change. In particular, reinforcement management is being

used with the helping relationship.

SUMMARY

This scenario provides us with examples of a patient in

different stages of the change process. This scenario also

provides us with examples of motivational interviewing

techniques that can be used to help our patients progress

through each stage. Therapeutic movement is one stage at

a time. Assessing the patients readiness to change is the

first task for the provider. Once we have determined where

our patients are along the continuum, our task is to facilitate

movement from their current position to the next stage.

An individually tailored, matched service is recommended.

The health care encounter consists of two parties, in

which both play a significant role in the dynamic process.

A provider who chooses not to utilize communication skills

that have been shown to improve the visit and the clinical

outcomes is doing a disservice to his or her patient. We

have the capabilities to positively affect the medical visit

and to influence health. Using specific communication

skills that enlist the patients active involvement in the

encounter, developing the discrepancies between the pros

and the cons of change, and mutually negotiating viable

options can shift a patient further toward adaptive healthy

behavior. Health promotion has been defined as the science and art of helping people change their lifestyle to

move toward a state of optimal health (ODonnell, 1987,

p. 4). The integration of Prochaska and DiClementes

Transtheoretical Model of Change and Miller and Rollnicks Motivational Interviewing techniques seamlessly

merge together to create an optimal patient encounter.

This article has discussed the importance of using a

model of change and motivational interviewing to improve

health. Health promotion into the 21st century demands

an approach that improves the ability of individuals to take

action. Taking action involves at least two of the levels of

action outlined in the Ottawa Charter (WHO, Health and

Welfare Canada, and the Canadian Public Health Association, 1986). It includes creating supportive environments

where clinicians take into consideration the life context of

their patients. In addition, it involves the development of

personal skills to promote health. The Jakarta Fourth Inter-

Shinitzky and Kub: Motivating Behavior Change 185

national Conference on Health Promotion has stressed that

one priority is that of empowering individuals (WHO,

1997). This entails reliable access to the decision-making

process and skills and knowledge essential to effect change.

Through the art of motivating, health care providers can

influence and empower individuals to positively influence

their level of health.

REFERENCES

Beckman, H. B., & Frankel, R. M. (1984). The effect of the

physician behavior on the collection of data. Annals of Internal

Medicine, 101, 692696.

Benjamin, A. (1987). The helping interview: With case illustrations. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Cassidy, C. A. (1997). Facilitating Behavior Change. American

Association of Occupational Health Nurses, 45(5), 239246.

DNofrio, G., Bernstein, E., & Rollnick, S. (1996). Motivating

patients for change: A brief strategy for negotiation. In E.

Bernstein & J. Bernstein (Eds.), Case studies in emergency

medicine and the health of the public (pp. 295303). Sudbury,

MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

DiClemente, C. C., Carbonari, J. P., Montgomery, R. P. G., &

Hughes, S. O. (1993). The alcohol abstinence self-efficacy

scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55, 141148.

DiClemente, C., & Prochaska, J. (1998). Toward a comprehensive

transtheoretical model of change. In W. R. Miller & N.

Healther (Eds.), Treating addictive behaviors (pp. 324). New

York: Plenum Press.

DiClemente, C. C., & Scott, C. W. (1997). Stages of change:

Interactions with treatment compliance and involvement. In

L. S. Onken, J. D. Blaine, & J. J. Boren (Eds.), Beyond the

therapeutic alliance: Keeping the drug-dependent individual

in treatment (NIDA Research Monograph 165). Washington,

DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Dijkstra, A., DeVries, H., & Bakker, M. (1996). Pros and cons

of quitting, self-efficacy, and the stages of change in smoking

cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64,

758763.

Donatelle, R., & Davis, L. G. (1998). Access to health. Needham

Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Edelman, C. L., & Mandle, C. L. (1998). Health promotion

throughout the lifespan. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Co.

Egan, G. (1998). The skilled helper: A problem-management

approach to helping (6th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/

Cole Publishing Company.

Fava, J. L., Velicer, W. F., & Prochaska, J. O. (1995). Applying the

transtheoretical model to a representative sample of smokers.

Addictive Behaviors, 20, 189203.

Hall, J. A., Roter, D. L., & Tand, C. S. (1988). Meta-analysis of

correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Medical

Care, 26, 657675.

Haynes, R. B. (1976). A critical review of the determinants

of patient compliance with therapeutic regimens. In D. L.

Sackett & R. B. Haynes, (Eds.), Compliance with therapeutic

regimens. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Haynes, R. B., Taylor, D. W., & Sackett, D. L. (1981). Compliance

in health care (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lee, P. R., & Estes, C. L. (1997). The nations health. Boston:

Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Levinson, W., Roter, D. L., Mullooly, J. P., Dull, V. T., & Frankel,

R. M. (1997). Physician-patient communication: The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians

and surgeons. Journal of American Medical Association, 277,

553559.

McConnaughy, E. A., DiClemente, C. C., Prochaska, J. O., &

Velicer, W. F. (1989). Stages of change in psychotherapy:

A follow-up report. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and

Practice, 4, 494503.

McGinnis, J. M., & Foege, W. H. (1993). Actual causes of death in

the United States. Journal of American Medical Association,

270(18), 22072212.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing:

Preparing people for change. New York: Guilford Press.

Miller, W. R., & Tonigan, J. S. (1996). Assessing drinkers motivation for change: The stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES). Psychology of Addictive

Behaviors, 10, 8189.

ODonnell, M. (1986). Definition of health promotion. Journal

of Health Promotion, 1(1), 45.

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model

of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

51(3), 390395.

Prochaska, J. M., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical

model of health behavior. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 3848.

Prochaska, J., DiClemente, C., & Norcross, J. (1992). In search

of how people change. American Psychologist, 47(9),

11021114.

Rollnick, S., Heather, N., Gold, R., & Hall, W. (1992). Development of a short readiness to change questionnaire for use

in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers.

British Journal of Addiction, 87(5), 743754.

Wissow, L. S., Roter, D., Bauman, L. J., Crain, E., Kercsmar, C.,

Weiss, K., Mitchell, H., & Mohr, B. (1998). Patient-provider

communication during the emergency department care and

children with asthma. Medical Care, 36(10), 14391448.

World Health Organization, Health and Welfare Canada, and the

Canadian Public Health Association. (1986). Ottawa charter

for health promotion. Copenhagen, Denmark: FADL

Publishers.

World Health Organization. (1997). The Jakarta declaration of

leading health promotion into the 21st century [On-line].

Available: http//www.who.int/hpr/docs/jakarta/english.html.

Вам также может понравиться

- Solution Focused Harm Reduction: Working effectively with people who misuse substancesОт EverandSolution Focused Harm Reduction: Working effectively with people who misuse substancesОценок пока нет

- Changing Trends in Mental Health Care and Research in GhanaОт EverandChanging Trends in Mental Health Care and Research in GhanaОценок пока нет

- The Role of Emergency Room Social Worker - An Exploratory StudyДокумент45 страницThe Role of Emergency Room Social Worker - An Exploratory StudyjHen LunasОценок пока нет

- Spices PDFДокумент2 страницыSpices PDFAnonymous S5UkdjJWAОценок пока нет

- Carl Rogers 1Документ10 страницCarl Rogers 1Monica S. SantiagoОценок пока нет

- A Cognitive Information Process Approach To Career Counseling The Many Major Changes of A College StudentДокумент13 страницA Cognitive Information Process Approach To Career Counseling The Many Major Changes of A College Studentapi-307225631Оценок пока нет

- Chronic Pain ACTДокумент8 страницChronic Pain ACTRan AlmogОценок пока нет

- Chapter 23 - Medication Interest ModelДокумент83 страницыChapter 23 - Medication Interest ModelNaomi LiangОценок пока нет

- Resident e Progress NotesДокумент2 страницыResident e Progress Notesapi-273537080Оценок пока нет

- Case-Anheuser Busch UpdatedДокумент12 страницCase-Anheuser Busch UpdatedJennifer Bello Araquel100% (1)

- Depression Care PathwayДокумент267 страницDepression Care PathwaydwiОценок пока нет

- Biopsychosocial ModelДокумент1 страницаBiopsychosocial ModelJames SkinnerОценок пока нет

- Depression Children PDFДокумент2 страницыDepression Children PDFConstanzaОценок пока нет

- SOAP Notes: HistoryДокумент5 страницSOAP Notes: HistoryRajveerОценок пока нет

- Assertive Community Treatment TreatmentOptions 2018Документ2 страницыAssertive Community Treatment TreatmentOptions 2018titik dyahОценок пока нет

- Motivational Interviewing: Application in Clinical PracticesДокумент24 страницыMotivational Interviewing: Application in Clinical PracticesElizabeth HoОценок пока нет

- Making ReferralsДокумент9 страницMaking Referralsglenn johnstonОценок пока нет

- Prochaska JO Velicer The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior PDFДокумент11 страницProchaska JO Velicer The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior PDFClaudio M. Cruz-FierroОценок пока нет

- P R O D U T I V I T Y: Absenteeism Turnover DisciplineДокумент30 страницP R O D U T I V I T Y: Absenteeism Turnover DisciplineShahzad NazirОценок пока нет

- Occupational Identity Disruption After Traumatic Brain Injury - An Approach To Occupational Therapy Evaluation and TreatmentДокумент13 страницOccupational Identity Disruption After Traumatic Brain Injury - An Approach To Occupational Therapy Evaluation and Treatmentapi-234120429Оценок пока нет

- Post Stroke Psychiatric DisordersДокумент52 страницыPost Stroke Psychiatric Disordersdrkadiyala2Оценок пока нет

- 2015 Final Case Studies Asam Fundamentals Final UpdatedДокумент68 страниц2015 Final Case Studies Asam Fundamentals Final UpdatedTrampa AdelinaОценок пока нет

- Assignment 3Документ12 страницAssignment 3Syed Muhammad Moin Ud Din SajjadОценок пока нет

- Assignment 1Документ4 страницыAssignment 1api-581780198Оценок пока нет

- Cns 780 Know The LawДокумент7 страницCns 780 Know The Lawapi-582911813Оценок пока нет

- Running Head: Writing A Treatment Plan 1Документ6 страницRunning Head: Writing A Treatment Plan 1Angy ShoogzОценок пока нет

- Extended Case Formulation WorksheetДокумент3 страницыExtended Case Formulation Worksheetbakkiya lakshmiОценок пока нет

- Grop No 1counseling ProcessДокумент23 страницыGrop No 1counseling ProcessHina Kaynat100% (1)

- Template For Clinical Progress Note June 2009Документ3 страницыTemplate For Clinical Progress Note June 2009Buthaina AltenaijiОценок пока нет

- Mock First Soap NoteДокумент7 страницMock First Soap Noteapi-372150835Оценок пока нет

- Older Adults and Integrated Health Settings: Opportunities and Challenges For Mental Health CounselorsДокумент15 страницOlder Adults and Integrated Health Settings: Opportunities and Challenges For Mental Health CounselorsGabriela SanchezОценок пока нет

- Writing Project - Soap Note MemorandumДокумент2 страницыWriting Project - Soap Note Memorandumapi-340006591Оценок пока нет

- My Safety Plan: You Deserve To Be Safe and HappyДокумент2 страницыMy Safety Plan: You Deserve To Be Safe and HappySaundra NguyenОценок пока нет

- RUNNING HEAD: The SoloistДокумент7 страницRUNNING HEAD: The SoloistMary Winston DozierОценок пока нет

- Behavioral InterviewingДокумент3 страницыBehavioral InterviewingMarsden RockyОценок пока нет

- Case Management Using CBTДокумент2 страницыCase Management Using CBTalessarpon7557Оценок пока нет

- Soap Note - ExampleДокумент1 страницаSoap Note - ExamplearchanabrianОценок пока нет

- Macro - CommunityДокумент2 страницыMacro - CommunityFaranОценок пока нет

- 10 Introductory Questions Therapists Commonly Ask PDFДокумент4 страницы10 Introductory Questions Therapists Commonly Ask PDFsamir shah100% (1)

- Case Note Excellent2 AnnotatedДокумент8 страницCase Note Excellent2 AnnotatedShubham Jain Modi100% (1)

- Electronic CigarettesДокумент2 страницыElectronic CigarettesLeixa Escala100% (1)

- Cognitive TherapyДокумент18 страницCognitive TherapyHaysheryl Vallejo SalamancaОценок пока нет

- Working With Older AdultsДокумент84 страницыWorking With Older AdultsdarketaОценок пока нет

- Motivational Interviewing Theoretical EssayДокумент6 страницMotivational Interviewing Theoretical EssayDanelleHollenbeckОценок пока нет

- Chapter 5 AnxietyДокумент16 страницChapter 5 AnxietyMark Jayson JuevesОценок пока нет

- Thesis Presentation 2Документ13 страницThesis Presentation 2api-457509028Оценок пока нет

- Peer SupportДокумент5 страницPeer SupportGillian FleuryОценок пока нет

- Clinical Social Work: Privilege FormДокумент1 страницаClinical Social Work: Privilege FormjirehcounselingОценок пока нет

- Perinatal Mood and Anxiety DisДокумент186 страницPerinatal Mood and Anxiety Disandifa aziz satriawan100% (1)

- Suicide Risk Assessment Guide NSWДокумент1 страницаSuicide Risk Assessment Guide NSWapi-254209971Оценок пока нет

- Mental Status ExamДокумент24 страницыMental Status ExamRemedios BandongОценок пока нет

- Pre Post TestДокумент4 страницыPre Post TestRainОценок пока нет

- What Is Problem Solving Therapy?Документ2 страницыWhat Is Problem Solving Therapy?Divaviya100% (1)

- C4C Upload of The U.S. EEOC Management Directive 110Документ358 страницC4C Upload of The U.S. EEOC Management Directive 110C4CОценок пока нет

- 3-3 - MasterTreatment Plan Update4-9-18newestGD7-9Документ1 страница3-3 - MasterTreatment Plan Update4-9-18newestGD7-9Rudy KolderОценок пока нет

- Postconcussive Syndrome (PCS) Clinical Practice Guideline: Occupational TherapyДокумент7 страницPostconcussive Syndrome (PCS) Clinical Practice Guideline: Occupational TherapyNicoleta Stoica100% (1)

- No Evidence of DependenceДокумент2 страницыNo Evidence of Dependencemago1961Оценок пока нет

- Adolescent Problem - DepressionДокумент27 страницAdolescent Problem - DepressionMeera AnnОценок пока нет

- NCE Study GuideДокумент62 страницыNCE Study GuideSusana MunozОценок пока нет

- Who Conselling For Maternal and Newborn Health CareДокумент18 страницWho Conselling For Maternal and Newborn Health CareDouglas Magagna MagagnaОценок пока нет

- Interrwerwevettia TaserapsfeuticaДокумент1 страницаInterrwerwevettia TaserapsfeuticaOrban Csaba DanielОценок пока нет

- RezultateДокумент3 страницыRezultateOrban Csaba DanielОценок пока нет

- Why Does Handedness Exist?Документ2 страницыWhy Does Handedness Exist?Orban Csaba DanielОценок пока нет

- Facultatea De: Psihologie Si Stiinte Ale Educatiei Sectia: Psihologie, Anul 3 (2014)Документ4 страницыFacultatea De: Psihologie Si Stiinte Ale Educatiei Sectia: Psihologie, Anul 3 (2014)Orban Csaba DanielОценок пока нет

- Family Guy S13e02Документ43 страницыFamily Guy S13e02Orban Csaba DanielОценок пока нет

- The Planning, Attention-Arousal, Simultaneous and Successive (PASS) Theory of IntelligenceДокумент1 страницаThe Planning, Attention-Arousal, Simultaneous and Successive (PASS) Theory of IntelligenceOrban Csaba DanielОценок пока нет

- Self ConfidenceДокумент56 страницSelf Confidenceaecelcas pelagio100% (5)

- HRM3704 Tut101 17Документ44 страницыHRM3704 Tut101 17MichaelОценок пока нет

- Ej976654 PDFДокумент8 страницEj976654 PDFRaniena ChokyuhyunОценок пока нет

- AppreciationДокумент7 страницAppreciationRalph Samuel VillarealОценок пока нет

- Organizational Behaviour Chapter II AДокумент78 страницOrganizational Behaviour Chapter II AAwol TunaОценок пока нет

- Stress AssignmentДокумент7 страницStress AssignmentMartin MbaoОценок пока нет

- The Essential Motivation Handbook - Leo Babauta PDFДокумент112 страницThe Essential Motivation Handbook - Leo Babauta PDFdidiertwОценок пока нет

- MGT502 Organizational Behavior All Midterm Solved Paper in One FileДокумент162 страницыMGT502 Organizational Behavior All Midterm Solved Paper in One FileMalikusmanОценок пока нет

- Writing A Statement of Teaching Philosophy - 1Документ8 страницWriting A Statement of Teaching Philosophy - 1Michelle Zelinski100% (1)

- 12324890001Документ416 страниц12324890001دنيا سلومОценок пока нет

- Marketing MNG NotesДокумент119 страницMarketing MNG NotesShipra AggarwalОценок пока нет

- VALS-2 Segment CharacteristicsДокумент1 страницаVALS-2 Segment CharacteristicsThaoОценок пока нет

- Self-Assessment 8Документ4 страницыSelf-Assessment 8api-720382735Оценок пока нет

- Change Management ToolkitДокумент84 страницыChange Management Toolkitgabocobain100% (4)

- Intership Report Meer-Ehsan-BillahДокумент21 страницаIntership Report Meer-Ehsan-BillahZahir Mohammad BabarОценок пока нет

- Customer Service ExcellenceДокумент6 страницCustomer Service Excellenceazlipaat50% (2)

- Character Formation With Leadership Decision MakingДокумент13 страницCharacter Formation With Leadership Decision MakingShaine Frugalidad II100% (4)

- Ashwini Chavan HR ProjectДокумент67 страницAshwini Chavan HR ProjectDivyesh100% (1)

- SSP 111 Material SelfДокумент22 страницыSSP 111 Material SelfKesia Joy EspañolaОценок пока нет

- Teaching SkillДокумент35 страницTeaching SkillGex AmyCha TtuChicОценок пока нет

- Sexual Health Education in Quebec Schools: A Critique and Call For ChangeДокумент9 страницSexual Health Education in Quebec Schools: A Critique and Call For ChangesyaОценок пока нет

- Intro To CS With MakeCode For MicrobitДокумент7 страницIntro To CS With MakeCode For MicrobitJerome CastañedaОценок пока нет

- Pendidikan Fisika, 5 (6) ,: Daftar PustakaДокумент7 страницPendidikan Fisika, 5 (6) ,: Daftar PustakaHerma SafitriОценок пока нет

- Esip Final Revision 2020-2-1Документ31 страницаEsip Final Revision 2020-2-1Divh Boquecoz100% (1)

- Unit 1 Understanding Teaching and Learning: StructureДокумент24 страницыUnit 1 Understanding Teaching and Learning: StructureSatyam KumarОценок пока нет

- HopeДокумент26 страницHopeRadhaОценок пока нет

- Consumer Buying BehaviorДокумент71 страницаConsumer Buying BehaviorSiva Ramakrishna0% (1)

- Posdcorb: Explain Planning Process / Steps in Planning ProcessДокумент7 страницPosdcorb: Explain Planning Process / Steps in Planning Processnishutha3340Оценок пока нет

- HR ContentsДокумент10 страницHR Contentsआशिष प्रकाश बागुलОценок пока нет

- Meditation, Restoration, and The Management of Mental FatigueДокумент27 страницMeditation, Restoration, and The Management of Mental FatigueBetzi RuizОценок пока нет