Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

School of Oriental and African Studies, Cambridge University Press Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

Загружено:

J. Holder BennettОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

School of Oriental and African Studies, Cambridge University Press Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

Загружено:

J. Holder BennettАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Science/Technology Interface in Seventeenth-Century China: Song Yingxing

on "qi" and the "wu xing"

Author(s): Christopher Cullen

Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol.

53, No. 2 (1990), pp. 295-318

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African

Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/619236

Accessed: 10-12-2016 08:03 UTC

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

School of Oriental and African Studies, Cambridge University Press are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African

Studies, University of London

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

THE SCIENCE/TECHNOLOGY INTERFACE IN

SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHINA:

SONG YINGXING X IM ON QI A AND THE

WU XING ii '

By CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

1. Introduction

This paper is a contribution to the study of the relations between science and

technology in seventeenth-century China.' I hope that its unusual perspective

may help to illuminate the problem of how these two areas of human activity

relate to each other in a more general context.

Outside the small group of interested scholars the relations between science

and technology are not seen as problematical. In the popular stereotype,

scientists are the people who make discoveries, while technologists simply find

out how to use what they have discovered. This crude view has some support

from historical fact. Over the last hundred years there has undoubtedly been a

steady flow of useful ideas from (for instance) the physicist to the engineer and

from the biochemist to the agronomist.

We must remember, however, that this pattern of relations is quite recent.

For most of human history it is very hard to find an example of any ironfounder, farmer, millwright, weaver or cook who was much helped in his or her

daily concerns as a result of the systematic thought of natural philosophers.

Even after the beginning of the Scientific Revolution in seventeenth-century

Europe it is acknowledged that for a long time natural philosophers learned

more from the practical experience of artisans and industrialists than vice versa.

Thus, for example, the improvement of the steam engine in the late eighteenth

and early nineteenth century was not a consequence of the development of the

science of thermodynamics, but was itself a major stimulus to theoretical

innovation in that field. The same can certainly be said in a number of other

areas.2

So far as China is concerned historical investigations along these lines have

scarcely passed the preliminary stage. Early in his great reconnaissance of premodern Chinese science and technology, Joseph Needham found himself drawn

towards the conviction that Taoism, which he characterized as 'a unique and

extremely interesting combination of philosophy and religion, incorporating

also " proto "-science and magic,' was 'vitally important for the understanding

of all Chinese science and technology.'3 He suggested that a distinctive

characteristic of the Taoists was a high valuation of the insights gained by

craftsmen and artisans of all sorts, and an emphasis on knowledge as the result

of empirical investigation rather than abstract speculation. Given these characI have received research and travel funds which have been helpful in the preparation of this

article from the British Academy, the Universities' China Committee, and the Research Committee

of the School of Oriental and African Studies. This help is most gratefully acknowledged. I would

also like to acknowledge helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article by Professor Nathan

Sivin, Professor T. H. Barrett, and Dr. M. A. N. Loewe. None of them is responsible for any

remaining errors and omissions.

2 The discussion referred to here can be followed in successive volumes of Technology and

culture, beginning with the symposium on 'The historical relation of science and technology', in

vol. 6, no. 4, 1965.

3 Science and civilisation in China, Joseph Needham et al. (1954-) [hereafter S.C.C.], vol. II, 33.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

296

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

teristics, he felt, it was no surprise that many of the achievements

science and technology could be shown to have Taoist connexio

birth of science requires the bridging of the gap between the sch

artisan.'4 Needham has continued to hold to his conviction

subsequent decades of research in the history of Chinese science tech

medicine, although he has not taken the topic of Taoist connex

further than he did in his original discussion. Amongst other

Needham's view of Taoism has drawn some assent, but the discus

succeeded in moving from the level of the general to the particular.

problem is perhaps that, given the non-exclusive nature of the label

applied by Needham, it becomes difficult to avoid circularity. It is ea

into a situation where any Chinese writer who takes an interest in t

artisans or in the processes of the natural world is ipso facto a Taois

influenced. Taoists identifiable through formal initiation into a know

not seem to have been more interested in knowledge-generating

were outsiders.5

But even if we put the question of Taoism to one side, the problem

Needham's hypothesis will not go away. It is generally acknowled

many centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, the achievemen

artisans and technologists were markedly in advance of those of

temporaries in Europe. What role, then, did contact between na

ophers and practical men play in the development of the rich

tradition of pre-modern Chinese scientific thought? This article is a

give a partial answer to that question.

2. The historical context of Song's work

An informed interest in scientific and technical matters was not

amongst members of the scholar-gentry elite in traditional Chinese

same could doubtless be said of the members of the social groups wielding

political power in Europe (or anywhere else for that matter) before recent

centuries. There were, however, some differences between conditions at

opposite ends of Eurasia, since in China the agenda of the imperial government

meant that it could not avoid direct concern with certain areas of science and

technology.

The prime representative of official science was astronomy. The cosmic

pretensions of Chinese rulers meant that their standing in the eyes of their

subjects was closely linked to their ability to promulgate an accurate luni-solar

calendar. The complexity of the task undertaken increased as the centuries

passed. By the first century B.C. the calendar included what was, in effect, a

planetary ephemeris, and the aim began to expand to include the prediction of

all predictable celestial phenomena. Much success was achieved, although

defects in cosmographical theory meant that solar eclipses remained just outside

the realm of certainty, and hence remained ominous.6 All this effort meant that

the astronomical bureau was an essential department of the central government,

and although its staff might not normally be drawn from the foremost

statesmen of the day, their role was certainly not unrecognized.

One famous example of a prominent statesman who was also a skilled

astronomer was Xu Guangqi t )J ' (1562-1633: baptised as Paul on his

conversion to Christianity). From his commanding position in the imperial

4S.C.C., ii, 131.

5 For a critique of Needham's position on the significance of Taoism and on his use of the term

' Taoist' to describe the positions of individuals, see Sivin (1978).

6 cf. Sivin (1969).

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

SONG YINGXING X ) : ON QI A AND THE WU XING Ei T

297

bureaucracy Xu sponsored the introduction to China of the new astronomical

techniques brought by the Jesuit missionaries, and was instrumental in the

translation of Euclid's Elements and other scientific and technical works into

Chinese.7 Xu's astronomical and mathematical attainments were of a very high

order, but rare as they might be among his colleagues, there was nothing in

principle anomalous in his possessing them. It was also quite in order, and

indeed essential, for a scholar-bureaucrat to take a detailed interest in technological matters of certain kinds: Xu's great compendium of agricultural

methods and machines Nongzheng quanshu ~j ilk a - was one of a long line

of similar Chinese works, many of them officially sponsored.8 Finally, Xu's

involvement in attempts to procure Portuguese cannon to stiffen Ming

resistance to Manchu incursions reminds us that a member of the imperial civil

service might well find himself with direct responsibility for military policy, or

even in operational command of forces on the ground. Under such circumstances, the need obviously arose for the compilation of manuals of military

techniques and armaments, and the surviving specimens of this genre are

important sources for the historian of technology.9

So there certainly were areas of science and technology in which the Chinese

scholar elite had by necessity to maintain a body of expertise, and although the

main highway to success did not lie through these regions they were by no

means off-limits to the orthodox. The resultant output of officially sponsored

literature is considerable. In such areas of proto- or pseudo-science as alchemy

or the techniques of siting buildings and tombs (often referred to in English as

' geomancy') the literature was, on the other hand, almost wholly unofficial in

origin. In the case of medicine, books were often the result of private initiative,

but were also frequently compiled under official auspices. But so far as

technology is concerned, once the limits of direct official concern are passed, the

picture is relatively barren. Thus there is no corpus of systematic works on the

practical aspects of such topics as mining, metal-working, paper-making,

ceramic manufacture or the exploitation of water-power, despite the great

accomplishments of Chinese artisans in these fields, and their great importance

to the economic functioning of the Chinese state. The broad category of

concerns that nowadays we would label as 'technological' was not seen as

constituting a related whole by pre-modern Chinese intellectuals, whose interest

in practical matters was in general ordered according to the administrative

scheme imposed by the imperial government's departmental structure. That left

clear places for armaments and agriculture, but the rest of the practical arts

were best left to those directly concerned with practising them or dealing in their

end-products. Such men were not, on the whole, likely to learn their business

from books or to write books for the instruction of others.

Against this background, it is of great interest that a contemporary of Xu

Guangqi and a fully accredited member of the scholar-gentry struck out along a

highly original path that marked him out as a clear exception to the general

trend. This was Song Yingxing X g , X, who lived from 1587 to about 1665

and is best known for his book Tiangong kaiwu X I Ir Tt (The exploitation of

the works of nature), a detailed survey of most aspects of the technology of his

day."? The copious and clear illustrations that appear in the various editions of

7 On Xu's life and work, see Hashimoto (1988).

8 For a discussion of these agricultural compendia see S.C.C., vi, 2, 6 55-92. Xu's book is treated

in pp. 64-70.

9On Chinese military manuals, see S.C.C., v, 7, 18-39.

10 For editions of works by Song Yingxing see bibliography. Tiangong kaiwu is translated into

English in Sun (1966) and Li (1980); which should be read together; Yabuuchi (1954) is an

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

298

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

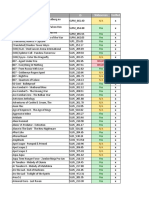

Song's book add much to its value. In the example shown here (fig. 1), iro

is being smelted using a double-action box-bellows to work the furnac

right, while on the left the molten cast iron is run into a puddling

conversion to wrought iron-or as the Chinese would have put it, ra

sheng tie t S is being converted to processed iron shu tie , Ri.

FIG. 1.

Song's book was unique in its coverage of such topics, and it was also unique in

its method of coverage. Xu Guangqi's great agricultural compendium was for

the most part a compilation (though a careful and critical one) of material from

previous treatises on the subject, and in this respect he followed in a long

Chinese tradition. Song, on the other hand, makes few explicit quotations from

written sources, and while he does not claim that everything he describes is the

result of personal investigation the flavour of his writing is highly suggestive of

first-hand experience."

important Japanese study of Song's book, translated into Chinese by Zhang and Wu (1959). For all

aspects of Song's life and work, including bibliographical problems, see the comprehensive study of

Pan (1981). In common with all students of Song Yingxing, I owe much to Professor Pan's

perceptive investigations, which have unravelled many problems about Song's activities. The topics

discussed in this paper are also touched on in Qiu and Qiu (1975) and He (1978). A recent study of

the concept of qi with much relevance to the contents of Song's essays is Cheng (1986).

1 Most of Song's mentions of written sources come in the introductions to each chapter, in

which he follows literary precedent to the extent of giving brief discussions based on material from

the pre-Han classics loosely related to the topic. In the bodies of the chapters, Song makes very few

references to the work of previous writers, and then only to express his disagreement. Despite this, it

nevertheless appears that he does use the contents of earlier agricultural manuals to some extent

(Professor Nathan Sivin, private communication). Presumably he found these in the Fenyi library, if

he had not already seen them (see below). Song must have known that his failure to quote explicitly

from written sources would have been regarded as an odd and unscholarly way to write. In his

preface he seems to be trying to disarm such criticism when he laments his inability to purchase rare

books and curios, or to call on the advice of other scholars, so that his book has had to be written

out of the limited information in his own mind.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

299

SONG YINGXING *Z , g& ON QI A AND THE WU XING i 4T

Unlike Xu Guangqi, Song Yingxing never achieved a position of any power

or influence. By the standards of his age and class Song's life must be judged as

no more than a very limited success, or at worst a moderate failure. He came of

a gentry family in reduced circumstances, and naturally tried to follow the only

formal career route open to him by taking the Civil Service examinations. He

passed the provincial examination with some distinction in 1615 at the age of

twenty-eight, but all his attempts at the metropolitan examination ended in

disappointment, an experience shared by many talented contemporaries at a

time when civil service recruitment was in a state of worsening chaos. When in

1631 he tried for the fifth and last time he was already forty-four. Thereafter, he

held a number of minor posts in provincial government, and with the collapse of

the Ming dynasty before the Manchus in 1644 he retired to private life. The

books for which he is famous today are the results of a brief burst of literary

productivity from 1636 to 1637, a period when he had the benefits of access to a

good library and a fair allowance of free time as Director of Education of Fenyi

e f county in Jiangxi il N province. The preface of Tiangong kaiwu is dated

to the fourth lunar month of 1637 (April 25-May 23); the evidence on which this

extensive and detailed work is based was clearly gathered over a number of

years. It seems very likely that Song's unsuccessful trips to the capital to take the

examinations had helped him to gather material from beyond his native

province. In the sixth month (July 22-August 19) Song wrote a preface to a

collection of essays under the head title Lun qi 4r 1(On qi), and in the seventh

month (August 20-October 17) he completed a discussion of various astronomi-

cal questions entitled Tan tian 9 ~ (On the heavens). At about the same time

Song compiled a collection of poems and a series of essays on statecraft. All four

of these opuscules were made widely available when they were reprinted in

1976.12

My main topic will be the first of Song's two scientific tractates, Lun qi. Let

me begin by listing main section headings; page numbers refer to the 1976

reprint.

51: Preface

52-63: Xing qi hua 7 X {f (The interconversion of solid objects and qi)

64-79: Qi sheng i _q (On qi and sound)

80-85: Shuifei sheng huo 71 4 H 'k (Water does not conquer fire)

12 See bibliography. The preface of this reprinted edition states that it is based on a Ming dynasty

print of the Chongzhen reign-period (A.D. 1628-44) 'discovered in the Jiangxi provincial library

during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution [1967-76].' The Chongzhen date must be deduced

from those given in the prefaces to three of the tractates, since there is apparently no evidence of a

printing-house dating. A few pages of this edition are photographically reproduced. These include

the collective title page for the four tractates supplied by the last private collector through whose

hands the work passed, Cai Jingxiang (1877-1952), after whose death it went to the Jiangxi library.

The reprinted edition makes no reference to Cai by name, and for this and other bibliographical

information the reader must turn to Pan (1981: 75-82). Pan makes it clear that the claim of the 1976

editors to be reprinting a ' lost ' work is a little over-dramatized. The existence of these tractates was

noted by scholars in the 1930s, and Pan himself consulted the Jiangxi library edition in 1963, making

a manuscript copy which he deposited in the library of Academia Sinica in Beijing. This in itself in

no way detracts from the usefulness of the reprint, which has certainly made Song's work much

more easily accessible. It must be noted that this book is published in simplified characters. Since

one traditional Chinese character is not in every case represented by a unique simplified character it

is not always possible to reconstruct exactly what Song wrote from this edition, and it is therefore

highly desirable that a facsimile text is made available as soon as possible. There is, however, no

ambiguity in any of the instances where the original Chinese text is quoted here, and all such

quotations have been transcribed into full form. Where works by modem writers are concerned,

however, bibliographical references have been given in the form used by the work in question. Pan

notes some errors of punctuation in the reprinted edition and, more disturbingly, states that there

are some errors in the transcription of characters (op. cit., 82). I have not noticed any obvious

instances apart from those mentioned by Pan, although the problem about the number of lacunae

discussed in note 50 may be a case in point.

VOL. LIII. PART 2

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

21

300

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

86-90: Shui chen 7k B? (Water and the atmosphere)

91-92: Shui feng gui zang 13 7J) fa X j (How water and wind retu

natural reservoirs)

93-95: Han re IS f (On cold and heat)

The main interest of this material is the original and highly flexi

which Song Yingxing uses the ancient concepts of qi i, and of t

~i I4 or Five Phases to make sense of a wide variety of physical p

Several other seventeenth-century scholars felt the need to re-e

traditional cosmological views in which these basic concepts played

in this context Song's readiness to rethink matters was not par

unusual.14 What is unusual in Song's writing is not the fact that he loo

concepts critically, but the fact that he applies them boldly to

particular physical instances in a way that is not common in the

Chinese scientific thought. What I mean will emerge more clea

discussion that follows.

3. Song Yingxing's cosmology

In the first place, let us deal with the question of the originality or otherwise

of Song's basic physical principles. At the beginning of his essay, he tells us that

'Everything between heaven and earth is either qi A or xing #J ... the

transformation from qi to xing and back again is something that people are

ignorant of although they take part in it every day.' 15

Of the two terms used here, xing is by far the easier to deal with: Song

Yingxing uses this word fairly consistently to mean ' solid objects' (xing AYf here

is a quite different word from xing f' 'phase'). Most sinologists nowadays

prefer to leave qi in transliterated form: there really does not seem to be any

suitable short English equivalent. Like most Chinese philosophical concepts,

the idea of qi was laid out in its basic outlines in the ferment of thought during

the last four centuries B.C. The problem for the modern reader trying to

understand the word in a given textual context is that this process did not result

in something he can readily grasp as a single concept. Senses that seem to be

simple and mechanical/material coexist with highly abstract ones apparently

unrelated to them, and no criteria exist for deciding which meaning is more

basic, or even which one is historically prior to another.16

Thus in some parts of Song's writing it would be sufficient to understand qi

as an all-permeating vapour, extremely subtle perhaps but still material in our

sense of the word. Solid objects, xing, are formed when this subtle vapour

condenses, and may revert back to vapour under the right circumstances. At a

wider cosmological level, qi is seen as just one stage in the unfolding of the

cosmic process: according to Song qi itself comes from the undifferentiated

void, xu RE, and eventually returns to it.17 We can recognize this at once as the

13 Gui zang is also the title of an alleged ancient divinatory manual grouped with the Yi jing in

some early references; no authentic text of this work has survived. From the context it seems that

Song has borrowed this phrase for its literal meaning, since he actually refers to the 'reservoirs' zang

of the winds in his text: see Lun qi, 91.

14 Readers unfamiliar with the concepts of qi and wu xing will find the clearest and most up-todate introduction at present available in Sivin (1987), ch. ii (from whom, with the kind permission of

the author and publisher, I have taken figs. (2) and (3)), together with full references to the literature

on the history of these concepts. For seventeenth-century criticism of traditional cosmology, see the

important study by John Henderson (1984), particularly chs. v-ix.

I5 Lun qi, 52.

16 See Sivin (1987: 46-53) for a summary of the development of the concept of qi, together with

references to historical studies such as Kuroda (1977) and Onozawa (1978). Cheng (1986) may also

be consulted.

17 Lun qi, 80.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

SONG YINGXING * JE I ON QI A AND THE WU XING Ti 4T

301

situation described by Zhang Zai g ~ (A.D. 1020-77): 'The great void can

never be without qi; qi inevitably gathers together to form the myriad things; the

myriad things inevitably disperse and return to the great void.' 8

The cosmology described in Song Yingxing's essay is rather more complex

than the simple outline given by Zhang Zai. In the first place, some entities do

not participate in the cyclical transformation between qi and xing: ' The sun and

moon represent the case where qi gathers together without going on to be

transformed to xing; earth and stones represent the case where xing is formed

without further transformation to qi.' 19

Important components of the material world do not fall definitely into either

category: 'Water and fire represent a case intermediate between xing and qi.' 20

Since, however, he lacks a term for this intermediate state, Song mostly

refers to water and fire collectively as being qi.21

Any consistent attempt to apply this fairly straightforward physical interpretation of qi throughout Song's writing will reveal its inadequacy, although it

is certainly true that under some circumstances the most obvious aspects of qi

are more or less mechanical and material. The same would, however, be true of

a human being falling from a high building, although no one would claim that

consideration of a person from the point of view of dynamics alone would

reveal much of their essential nature. Just as Mozart would reveal more of his

real capacities seated at a keyboard rather than in free fall, qi unfolds more of its

nature when we see it in its most complex role as the basic endowment of

vitality-the breath of life, pneuma, that enables living things to function. This

functional role includes all processes, from the basic physiological ones of

respiration and digestion to those of perception and aesthetic and moral

judgement in human beings. At this level qi is less and less clearly any kind of

substance as we might recognize the term, and seems rather to refer to the

organized activity or energy perceptible in material structures such as the

human body. As Nathan Sivin has put it: 'We might define [ql]... as simultaneously " what makes things happen in stuff " and (depending on context)

"stuff that makes things happen " or " stuff in which things happen ".' 22

If we investigate Song's attitude towards the theory of the Five Phases, wu

xing shuo i Jf -; the situation turns out to be very interesting. Like the idea of

qi, the scheme of the Five Phases had its main growth in the last few centuries

B.C. The motivation behind the five-phase scheme was the wish to focus on types

of processes or types of phase within larger processes seen in cyclical terms.

These phases were named after five naturally occurring entities seen as

exemplifying their characteristics: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. One of

the most ancient texts (the Hong fan St X' Great Plan' section of the Shang

shu fA' * ' Book of Documents ', before ?350 B.C.) explains that: ' Water is said

to soak and descend, fire is said to blaze and ascend, wood is said to curve and

be straight, metal is said to obey and change, earth is said to take seeds and give

crops.' 23

18 Zhang Zi zheng meng zhu, 1, 5. This is the edition with the important commentary of Wang

Fuzhi, on whom see below n. 39.

19 Lun qi, 52.

20 Lun qi, 52.

21 For instance in Lun qi, 83.

22 Sivin (1987: 47). In modem terms as Sivin notes, we might say that pre-modern Chinese

thought lacked separate concepts to distinguish energies from their carriers.

23 Karlgren (1950: 30). The set of five phases was only one of a considerable number of five-fold

classifications of types of thing or activity current in the late first millennium B.C. although it came to

be seen as in some sense underlying or being correlated with all other five-fold sets. While five-fold

schemes became dominant, there were also schemes based on the number three, four, six, eight,

nine, ten and twelve. On these questions see Henderson (1984), 7-8.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

302

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

More abstractly, the Five Phases can be seen as subdivisions in

alternation between Yin [i and Yang i, the positive and negativ

any cycle (see fig. 2).

Equivalences between Yin-yang and Five Phases

Wood Immature yang Yang within yin

Fire Mature yang Yang within yang

Earth Central house, harmony

Metal Immature yin Yin within yang

Water Mature yin Yin within yin

FIG. 2

The sequence in which they are shown here is seen as the sequence of natural

growth, the sequence in which a process is evolving in an orderly and

undisturbed way. Perhaps the original rationale of this order may be linked with

the natural observation that wood can feed fire, fire produces ashes (i.e. earth),

metals can be extracted from earth, and water appears on cold metals by

condensation, while the growth of plants from water takes us back to wood. In

fig. 3 the natural production order runs clockwise round the arcs of the circle.

FIRE

EARTH

WOOD

Relationship of the Mutual Production and

Mutual Conquest Sequences of the Five Phases-

FIG. 3

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

SONG YINGXING X Y%, S ON QI A AND THE WU XING i 3T

303

If, however, we skip alternate phases by moving along the straight lines we

produce the so-called conquest sequence, in which each phase is seen as being

overcome by its successor. Once more, it is possible to produce a crude post hoc

rationalization of the sequence (wooden tools dig up earth, earth dams up

water, water puts out fire, fire melts metal, metal cuts wood), but it must be

emphasized that such rationalization played no role in the theoretical applications of the scheme. In medicine, for example, healthy physiological processes

would be linked with the natural production sequence, while the conquest

sequence marks the order of pathological change. Five-phase language was used

in realms of discourse to us as far removed as medicine, as cited here, and the

analysis of the cosmic processes felt to underpin changes of rule within the

Chinese state.

While Song speaks of all Five Phases shui, huo, mu, jin, tu 7 ) A * _ ?t

(water, fire, wood, metal and earth) it becomes clear that he does not think of

them as simply an abstract sequence of phases of equal status linked in an

unending cycle of production or conquest. Thus both wood and metal are said

by Song to contain water and fire; earth, it is implied, contains neither.24 Song's

wood and metal are on most occasions he discusses them simply the stuff that

trees and cooking-pots are made of, and the water and fire they contain can be

made to manifest themselves in an umambiguously physical way. In such

instances Song seems to use the names of some of the Five Phases to refer to

different kinds of stuff which compose, or at least play a part in the make-up of

more complex substances: for examples see section 6.

' So Song's Five Phases are something like five elements, are they?' the non-

sinologist will quite reasonably ask. Such a questioner will be unaware of the

embarrassment resulting from this innocent query. The fact is that it is now

more or less agreed amongst Western sinologists that to translate wu xing as

' five elements' is in most contexts to perpetuate a misunderstanding about the

meaning of the term which goes back to the polemics of seventeenth-century

Jesuit missionaries. In their eyes, the wu xing were simply inferior competitors

for the place occupied by the four Aristotelian elements of earth, air, fire, and

water.25 But as Joseph Needham pointed out a quarter of a century ago, the

conception of the wu xing ' was not so much one of a series of five sorts of

fundamental matter (particles do not come into the question), as of five sorts of

fundamental processes. Chinese thought here characteristically avoided sub24 Lun qi, 83-4. Song points out that water appears when metal is rested on earth but that this

does not occur when one piece of earth is placed on another. Thus metal contains water, unlike

earth. Presumably the reference is to the dampness appearing when a large metal object is left on the

surface of the soil. We would now of course interpret this phenomenon as due to the condensation

of water vapour from the soil on the cold metal, thereby proving the opposite point to that deduced

by Song, a neat example of the meaninglessness of observation detached from a theoretical

framework. As for metal containing fire, no fire results when one stone (here taken as equivalent to

earth) is ground against another, but fire does appear when metal strikes on stone. Thus metals

contains fire, unlike earth. The arguments used by Song to show that living wood contains both

water and fire are set out in section 6 below. So far as differences in status between the five phases is

concerned, this was by no means an unprecedented departure. Dong Zhongshu in the Western Han

dynasty and Zhu Xi under the Song had both given primacy to the phase of earth: see Henderson

(1984) p. 129.

25 Thus in a work in Chinese completed in 1608 Matteo Ricci stated that' What are called xing

IT are what all things come forth from. Thus xing means " origin ", yuan 7Y. Now xing must be

completely pure, without one being mixed with another or containing another.' Metal and wood

cannot be elements, since firstly they are not widespread constituents of the material universe, but

principally because they are not pure substances: 'who is unaware that metal and wood really

contain a mixture of water, fire and earth?' See Qian kun ti yi, 1,10 Oa. One wonders on what Ricci's

assurance of assent on this last point was based. On the one hand he may simply have been taking

the Aristotelian viewpoint for granted, but this seems unlikely given the trouble he usually took to

start from where his Chinese reader would find himself. Could he perhaps have been aware of what

Zhang Zai had said on the subject? See section 6 below and nn. 65, 73.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

304

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

stance and clung to relation.' 26 It is certainly the case that for mos

history the wu xing were definitely process-phases rather than kind

None the less, it is very hard to read Song's work without t

conviction that for him, in several central instances, the wu xing ar

stuff, and that at least water, fire, and possibly earth, are bas

ingredients of matter to look rather like what pre-modern Euro

have called elements. Why Song should have taken such a radical

route from most other Chinese natural philosophers is a fascinating

question to which I hope to provide a partial answer later in this

4. Qi and Xing

Space does not allow a detailed exegesis of Song's work here. W

therefore do is to summarize a few of the most interesting poin

makes in his essays without attempting to recapitulate his full argum

The first essay in his Lun qi tractate is entitled Xing qi hua f

interconversion of solid objects and qi'). As its title implies, Son

explain how this interconversion can be seen at work behind the app

the world we perceive.

In the first place, he suggests, the growth and decay of living matt

example of how qi is transformed to xing. Plants grow by transform

flowing up through the earth into xing; when they decay or are bur

proportion of their mass and volume vanishes, clearly having been t

back to qi. Song is prepared to speak in quantitative terms:

[when wood has been burned] if one balances [the ashes] against th

of what was there originally, less than one part in seventy remain

compares it with the original quantity (duo gua ; g [? presum

intended, since weight has already been mentioned]) less than

fifty remains.27

Given the distinction between mass and volume ratios made here, it is

difficult to avoid the conviction that Song had actually done some measurements to determine how much solid matter had been converted to qi in this case.

According to Song, even the ashy residues which remain eventually revert to qi.

Since he believes that earth is a specially stable form of solid body which does

not revert to qi, it is necessary for him to deny that these residues can become

earth. If this was the case, he argues, the ground level would rise appreciably

with the accumulation of extra earth over the centuries.28

So far Song is simply developing physical concepts that are not fundamentally novel in a Chinese context. There is however, something new in the way he

introduces the dimension of time into the discussion. In the management of any

technical process, ranging from the smelting of metals to baking a cake, it is

often little use merely to know that the process will take place under certain

conditions of temperature, etc.; what really matters is how slowly or rapidly it

will take place. It is characteristic of Song's distinctively practical orientation in

his discussion of xing/qi transformations that he concerns himself greatly with

the question of the rate at which they will occur.

26 S.C.C., II, 243. Regrettably, Needham did not abandon the older usage he criticized so

effectively. See also the discussion in Sivin (1987: 70-80).

27 Lun qi, 53.

28 Lun qi, 53-4. For the extension to include carnivores, see Lun qi, 59. Song does not believe that

earth is totally inert; earth can produce stones, which themselves eventually revert to earth, and

similarly ceramics revert to earth. This is however a closed' minor cycle' outside the main current of

interchange between qi and xing; see Lun qi, 61-2. Dr. Michael Loewe has pointed out to me that the

earth-+ceramics- earth cycle is referred to in Huai nan tzu & j T- 7,4a (Sibu congkan edition).

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

305

SONG YINGXING $R H & ON QI A AND THE WU XING i Tf

In the first place, he points out that the intermediate status of water and fire

between qi and xing means that it is easier for them to go either way, so

transformations involving them are likely to be more rapid than those involving

a direct interchange between qi and xing.29 Evaporation of liquids is certainly

seen much more commonly than sublimation of solids. His main insight into the

question of the rate of processes comes, however, in his idea of what we may call

rate reversibility, a principle which may be summarized as follows:

A solid body will in general revert to qi at a rate which is comparable with the

speed with which it was formed in the first place.

For example, a plant that grows in a few weeks will decay completely in a

similar time, while the wood from an ancient pine will last for about as many

centuries as it took to grow. The corpses of children decay rapidly in the tomb,

while the body of a centenarian corrupts very slowly.30 Most interesting in the

technological context is his discussion of this rate-reversibility principle as

applied to metals. Song begins by pointing out that there is a very great

difference in the rates at which different metals are extracted from the earth. He

lists the following figures, which give us some idea of how Song thought of the

relative rates of production of metals in his day:

Metal Overall Index Production Ratio

Iron

20,000

Lead and Tin 2,000

Copper

1,000

Silver

Gold

10

10:1

2:1

100:1

10:1

The

figures

in

by

Song

for

suc

list,

Song

notes

and

rusting

at

a

rapidly

even

wh

that

are

produc

are

produced

w

biological

grow

despite the very widespread production of iron, this commodity is not, he

claims, becoming more abundant. It is interesting to note in passing that Song

clearly regards human activity in industrial production as an integral part of the

stable cosmic ecology rather than as an interference with it.

29 Lun qi, 55.

30 Lun qi, 57-8.

31 Lun qi, 62-3. It is interesting to note that in his discussion of the metals in the Tiangong kaiwu

Song states that the price of gold (presumably per mass) is 16,000 times that of iron, a figure in fair

correspondence with the 20,000:1 production ratio given here. See Tiangong kaiwu (1978 edition),

335. The order of the list agrees well with the electrochemical series, in which the metals mentioned

here rank as iron, tin lead, copper, silver and gold in order of decreasing activity. Song may have

arrived at his list on the basis of actual figures for production, or price data, or just a subjective

impression of how readily metals corroded, or most probably a mixture of all three. The association

of lead and tin in the list may be linked to the fact that according to Song tin is always used with an

admixture of lead to cure its brittleness: see Tiangong kaiwu, ch. 14, section 8, p. 370.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

306

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

5. Sound

Song Yingxing's writing on the subject of sound is one of the most

interesting parts of his work. It is also one of the most difficult parts to discuss

without giving a misleading impression of its nature. The problem is that Song

writes in a way that makes it easy for the reader to assume mistakenly that this

Ming dynasty scholar shares the same assumptions about the nature, produc-

tion and propagation of sound as a modern physicist. It is worth while pausing

for a moment to say something about the modern view of sound before we

consider Song's account.

Viewed in its widest sense, the act of hearing involves phenomena at various

levels of complexity. At the highest level of all we have the observer's actual

consciousness of hearing something. What he is conscious of hearing will be

heavily conditioned by the unconscious effects produced by individual

experience and social training, and by expectations based on the immediately

past situation. At the neurological level a complicated sequence of information

processing goes on to determine which sounds are worthy of close attention,

and what harmonic components are present.32 The ear-drum and the apparatus

by which it stimulates the auditory nerves forms the interface between these

interior levels of activity and the vibrations of the air in contact with it. Such

vibrations can be transmitted through the air from some vibrating object by

means of longitudinal waves.33 For most of the last three centuries the

physicist's approach to sound has proceeded on the assumption that the

mechanical phenomena outside the ear were the appropriate objects of attention. These were 'objective', and the 'subjective' experiences of the observer

only entered into the discussion when the terms of his observer-language could

be mapped simply onto mechanical properties of the vibrating air or other

medium. Thus the physicist could talk about 'loudness' in terms of the

amplitude of oscillations of air molecules, and about 'high pitch' in terms of

the high frequency of those oscillations. And such has been the success of this

approach in terms of the ability to make mathematical predictions that sound is

commonly taken to be nothing but vibrations in the medium outside the

observer.

It is possible to read Song's work on sound as if he was giving such a

reductionist account of acoustics as the one just outlined. As we shall see, the

role played by qi seems very like the role played by air in the modern account,34

and there is certainly much about mechanical disturbances of various kinds.

Towards the end there is even a short comparison of the spreading of sound

from its source to the spreading out of water ripples. The temptation is read

modern physics back into Song's writing is thus very strong. If we do so,

however, much of the real character of Song's thought will be obliterated in the

process. Instead of seeing a powerful mind trying to make sense of a confrontation of traditional concepts with empirical observation, all we shall be left

with is a rather frustrating encounter with a writer who refuses to state the

obvious clearly, and obscures his basic principles under a mass of irrelevancies.

In fact, Song Yingxing was neither a modern physicist nor a confused thinker,

as I hope to show in what follows.

32 In this respect the ear functions as a 'Fourier analyser', unlike the eye, which cannot

distinguish a mixed colour into its component hues.

33 Longitudinal waves, in which the oscillations of small masses of air about their unchanged

mean positions occur parallel to the direction in which the disturbance is spreading, are to be

distinguished from transverse waves, in which the oscillation is at right angles to the direction of

propagation of the wave. Well-known examples of transverse waves are ripples on the surface of

water, and waves on a vibrating string.

34 But see section 7 below, in which Song distinguishes the merely material substance of the

atmosphere from the life-giving qi which pervades it.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

SONG YINGXING $ R, R ON QI A AND THE WU XING 1i fT

307

How far Song was from reducing the concept of sound to coldly objectified

statements about the motion of dead matter emerges in his first few words on

the subject.

How subtle is the way of sounds and musical notes! The sounds of things

vary in a myriad ways, but the sounds made by the human [voice] can

imitate them all. No sound is harsher than that of the detonation of a gun;

no sound is more delicate than that of a well-tuned zither; no sound is more

full of delight than that of orioles in converse; no sound is more plaintive

than a pig under the knife. Changes of musical mode [conveying different

moods] certainly have some rough semblance [to the range of feeling

conveyed by such sounds]. If it was not for the fact that [human beings]

possess qi in all its completeness, how could this be so? 35

The emotional and aesthetic content of sound is thus part of its essential

nature rather than something confined to the subjective response of the

observer. The crucial link is of course the concept of qi introduced at the end of

the passage. Shortly afterwards Song continues:

Human beings live because they have received [an endowment of] qi. When

there is qi there can be sound, and sound returns to qi. Now when solid body

(xing) transforms to qi it returns to it very slowly, while when sound returns

to qi it does so in an instant. The sounds produced by human beings come

forth from the viscera [where the body's qi is stored], are modulated by the

lips and tongue, and then have to make contact and harmonise with the qi in

empty space [outside the body]. [To see that this is necessary] if the mouth

and nose are blocked what is outside cannot enter and harmonise [with what

is within] and what is within can only rise up to the roof of the mouth and

make an obscure grunting noise. In the human body the father's seminal

essence and the mother's blood are conserved in the ' reservoir of qi' and in

the ' gate of life '.36 Whether an individual's ' sound qi' is large or small,

short or prolonged, depends on the embryonic endowment and not on the

strength of effort made.37

Sound is thus produced by qi, and seems to share with qi the distinctive

combination of statuses as agent, patient and process which makes' qi' so hard

to translate.

Now since qi is always present, why is it that sound is not likewise always to

be heard? Song is clearly aware of the problem:

Qi is basically a continuous and homogeneous thing (hunlun zhi wu

X1 i1[ ; j ). Every tiny part has the principle in it [capable of] producing

sound, but it cannot do so by itself.38

Sound is produced, he says, whenever the qi is disturbed in some way.39 Two

lots of qi may rub against one another, as in the case of the wind; a special case

5 Lun qi, 64.

36 On the nature of these traditional anatomical entities see Sivin (1987: 155 and 120).

37 Lun qi, 64-5.

38 Lun qi, 66. The beginning of this section seems slightly disordered. As we shall see, the passage

quoted is followed by descriptions of ways in which qi can be made to produce sound, but it is also

preceded by similar instances, which would seem to belong after it with the other examples.

39 The core of what follows is clearly inspired by the writing of Zhang Zai in the eleventh century,

even to the extent of Song copying the precise wording in a number of places. Zhang says' Sound is

produced whenever solid bodies or qi strike together. [The striking together of] two lots of qi is

evidenced in such phenomena as the rolling of thunder echoing in a valley; [that of two bodies] in a

drumstick beating a drum; solid body strikes qi in the case of [beating] wings, a fan, or a sounding

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

308

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

of this is when the qi of a human being rubs against the qi of the outside w

in the case of playing a reed-organ. Something may impact on the qi, as w

flying arrow; the qi may be divided, as when a whip is lashed through th

may be shaken, as when a string is plucked; it may be pulled apart, as wh

is torn, or brought together by clapping hands. When one body suc

hammer strikes another it carries some qi along with it, and the qi takes

the impact. In all these cases the seat of the sound is not in the actual

involved (which only serve to disturb the qi). Since any disturbance in the

away very rapidly the impacts, etc. just detailed have to take place rapidly

perceptible sound is to be produced.40 The discussion continues with a

on the final point that the clapping of hands etc. must be rapid in or

produce sound. Why is it that a high waterfall produces a loud noise w

the fall of water from a pot hardly makes any sound at all, despite the fa

both material and process are the same? The reason is that in the case

waterfall the qi possesses shi ' 'advantage of position' by reason of th

drop involved. Similar examples follow, such as the fact that there is

noise when gold and silver are divided by the impact of an axe, but little

when they are cut with snips.41 Despite these provisos, the important poi

notice in all this is that sound is essentially produced by any disturbing p

which triggers the li _ principle within the qi into being realized as

Vibration is only one of the ways through which the li can be actualized.

Song's next three sections are concerned with the production of sou

such implements as musical instruments.42 Consider the loud sounds p

by bells and drums: ' Is the sound produced by the metal and the drumski

does it come from the qi? 43

Song insists that the second answer is the correct one. The qi inside

instrument is stimulated to produce sound, and it immediately commu

this to the qi outside. It is easy to show that it is the qi rather than t

structure of the instrument that plays the essential role:

Suppose that the sound is not produced by the qi. Try stretching a dru

on the surface of the ground, or filling up a bell with earth. What sou

there then? 44

Similarly, if the bell-wall or the drumskin are made thicker and thick

volume of sound heard diminishes, showing clearly that something is

transmitted through the solid substance to the outside. Song now thinks o

apparent counter-instance and disposes of it neatly:

Someone might ask' if you hang up a sounding-stone and strike it, it e

penetrating note despite the fact that it has no hollow inside it [to conta

arrow; qi strikes a solid body in the case of a man sounding on a reed-pipe' (Zhang Zi zhe

zhu, 90-91, cf. Kasoff (1984: 38)). Song has departed from Zhang's model in that he insists

when two solid bodies strike together the significant interaction involves qi: see bel

interesting to note that in his commentary on this part of Zhang Zai's work Wang Fuzh

(1619-1692) seems to follow the same line: 'when the drumstick is whirled the qi follo

strikes on the drum, so here as in every other case qi is involved' (op. cit., 91). This is of

exactly what Song says is happening when a hammer hits something: see below. There

indications that Wang had read Song's astronomical tractate Tan tian which circulated with

qi (Pan, 1981: 97) and it certainly seems likely that Wang was influenced by Song at this p

also n. 68.

40 Lun qi, 66-7, with slight reordering to deal with the problem in n. 38.

41 Lun qi, 68.

42 Lun qi, 69-74.

43 Lun qi, 69.

44Lun qi, 69.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

SONG YINGXING XZ f%, ? ON QI A AND THE WU XING ~i fT

309

What do you make of that?' I reply that what is going on is that the

suspended stone forms a barrier between the continuous qi on either side of

it. If you strike it from one side the qi on the other side responds. It is the

same principle as the bell and drum. Supposing that the sound was produced

by the stone rather than by the qi, what kind of sound is produced when the

stone is placed flat up against a wall and struck?45

It seems then that the role of the solid material of which the instrument is

made is to allow the qi within the instrument to make contact with the qi

outside. Song thus goes on to discuss this process of transmission in detail.

Some things will allow qi to pass through, but others will not: this is linked to

the fact that qi contains the ' spirits' shen ji of water and fire.46 Qi transmission

from inside a drum is easily understood, since wood is naturally porous. But

what about the metal of a bell? Now when a metal instrument is being cast, the

metal in the furnace reveals the watery part of its nature as it melts. When this

watery nature unites with fire, we are told, the solid metal appears: it is clear that

Song regards the cooling of the metal as is solidifies as a ' swallowing-up' of the

fire into a unity with water to form the solid. A well-made bell should unite the

qi of the Five Phases, so it is not to be wondered at that it should readily

transmit qi and so pass on sound.47

For qi to. pass easily through a body, it is not enough for that body to be

permeated by qi (as are all bodies strictly speaking). If this was so, all bodies

would transmit sound equally well. In some bodies the qi is so to speak

'jammed', and no more qi can get through the barrier so formed.48 This is the

explanation of why a fired porcelain cup rings when struck, although it gives no

note when in the unfired state. When the cup is drying after it has been thrown:

The water [from the clay] and the fire [from the sun] come together, and lock

on to the body of the pot. Thus when it is struck from the outside [the qi]

within does not respond and there is no sound. But when it is put into the

kiln in close contact with the fire, the affinities which were formerly bound

up melt away, and the essence of fire opens up the material, so that the

earthy substance changes its form. Now if it is struck once a clear sound

rings forth.49

In conclusion Song gives a brief statement of the close link between qi,

sound and the materials from which instruments are made:

Thus Heaven produces the five qi, so that there are the Five Phases. Each of

the Five Phases has the sound of its own note, and the notes of water and fire

permeate through the interior of metal and earth.50

It is clear that Song is far from any explanation of the qualities of sound in

terms of simple mechanical disturbance of qi. Sound is not a mere matter of a

45 Lun qi, 71-72.

46 See section 6 below.

47 Lun qi, 71.

48 As an illustration of this state of affairs, Song gives the example of a pastry withdrawn from

the steamer when half-cooked. If it is later put back again the middle will never be completely

cooked because the qi of water and fire have become solidified in the outer layer so that further qi

cannot get through. The same is said is to true of a half-cooked egg. I must confess to not having

tested these statements empirically, though they do not strike me as very plausible.

49 Lun qi, 72.

50 Lun qi, 72. There now follows a clause with two illegible characters in the original text, ci ke yi

tui wu yin [ ][ ]yi f- J, X ~i- [ ] [ ] . If one restored the lacuna as zhi li J E

the clause might be read as' This is the way one can infer from the principle of the five notes [of the

pentatonic scale],' but the ending of the clause with yi alone does not seem stylistically satisfactory.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

310

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

shaking of the qi. If this was so it is hard to see why Song thinks

transmission of sound as involving qi penetration through vessel wall

than the simple transmission of vibration from the qi inside a vessel to qi

by means of vibrations in the wall itself. It will be recalled that Song ha

said quite explicity that sound is not produced by the skin of a drum

metal wall of a bell. However, as the next two sections reveal, the fact th

high-level properties 51 does not mean that it can never be talked about

involving simple language about displacement or disturbance.

In his next section Song asks why, in general, musical instruments ten

rounded in shape rather than square. The answer he gives is clear:

When the qi in the central hollow [of the instrument] responds to the o

[stimulation], one wants this to happen uniformly and simultaneously

you have any squareness, then one part [of the qi] will be stimulate

another part is quiescent, and one part will be hurried while another i

As a result [the disturbances] will mingle confusedly in the middle

instrument, and the sound will not be worth listening to.52

The general principle that roundness produces a more tuneful effe

squareness is then illustrated with reference to drums, bamboo pipes, th

made by a door-post turning in its socket, and even the blaring of the animal

horns and conches used by the northern barbarians, of which Song says that

'The sound is loud, but it is hardly music.' 53

In the last section a crucial point in Song's argument is the tacit assumption

that the stimulation of one part of the qi takes some time to be communicated to

the rest. Song now goes on to use an analogy for the way such stimulation is

propagated that reinforces this impression of his view. He notes that the point

has already been made clearly that sound is generated when qi is struck or

divided.54 But it is likewise clear that sound can be heard far away from the site

of the stimulation. In the extreme case of a cannon being fired in a mountain

valley the sound may be heard for 10 li (about three miles). 'In general,' he

states 'all such phenomena are due to moving qi.' 55 There then follows

immediately a short but highly interesting passage.

When a body impacts on qi, it is like disturbing water. Water and qi are both

easily moved things. If one throws a stone into water, the area of water

surface that actually meets the stone is no bigger than the palm of a hand,

but the patterned ripples spread out one after another, and are not yet

exhausted after they have covered ten feet in all directions. When qi is

disturbed, it is like this. Only when the disturbance has been highly

attenuated does it become inaudible.56

51 As exemplified below in Song's explanation of perception in terms of the liang zhi ' innate

knowledge' embodied in that part of the human body's qi involved in hearing.

52 Lun qi, 73.

53 Lun qi, 74.

54 As Song says later in this section:' If there is quiescence, then qi will be quiescent and there will

be no sound. If there is motion, then qi will be in motion and there will be sound' (Lun qi, 76).

55 Lun qi, 75.

56 Lun qi, 75. For a discussion of other possible instances of the use of this analogy, see S.C.C.,

iv, 1, pp. 8 and 202-204. The (largely Western Han) source quoted in the second of these (Chun qiu

fan lu fk 1]k g i Juan 7, section 81, 8b-9a in the Sibu congkan edition is referring to the

transmission of good and bad moral influences through the cosmic qi rather than to the

transmission of sound, although it compares the ease with which the qi transmits such moral

influences to the ease with which the disturbance caused by a falling stone spreads out over the

surface of water. The text of the third century A.D. fragment by Liu Zhi liJ ;, quoted in the first

reference is taken from a fragment collection which appears to miscopy its original at a crucial

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

SONG YINGXING X jf & ON QI A AND THE WU XING i fT

311

Enough has by now been said to make it clear that it would be unwise to

credit Song with a wave theory of sound on the basis of this passage alone. As

his last sentence makes clear, all Song wants is an illustration of a disturbance

spreading out from a source, and undergoing gradual attenuation with increasing distance travelled. The fact that the example he chooses is an undulatory

disturbance does not mean that he believes that sound is an undulatory motion

of the qi.

The remainder of Song's text may be summarised briefly. The number of

different sounds is as infinite as the variety of bodies that can produce sound.

Sound is perceived through the interaction of that part of the vital qi of the body

which has its seat in the gall-bladder and communicates with the exterior

through the ear. This qi possesses the liang zhi ' X ' innate knowledge' which

enables it to distinguish the content of the sounds heard.57 If the sound is very

violent, as in an explosion, the shock given to the internal qi may damage the

viscera (which are the body's reservoirs of qi) and cause death. On the other

hand music of the appropriate kind can calm and harmonize the qi, so

producing a well ordered mind.58 He ends by reviewing the variety of sources of

sound in the natural world, from the smallest insect to the roaring of thunder.

6. Water and fire

We may perhaps best use the remaining space in considering a further essay

in the Lun qi tractate, Shuifei sheng huo 7kc T f k] (Water does not conquer

fire). This reveals more about the special role of these two of the wu xing in

Song's thinking. Song begins by denying that water ' conquers ' fire as laid down

in the traditional xiang sheng +tg f 'mutual conquest' order shown in fig. 3.

On the contrary, Song maintains, water and fire appear as a result of the

differentiation of the qi whose source is the void, and retain a very strong

point (Quan Shang Gu San Dai Qin Han San Guo Liu Chao wen, Jin wen, 39, 6b, p. 1685 in the 1985

reprint). Instead of reading chu shi er si chu zhe shui qi zhi tong ye J 3 jfjji _ ~ 7k A,

- A[|the source in the eighth-century A.D. Kaiyuan zhanjing JXC &! S (ch. i, p. 26b in the

Hengdetang zangban edition) has yun ` for ci ~, so that the reference is to the appearance of

clouds rather than to '(ripples) spread(ing) forth one after another' as Needham renders it. An

interesting source not mentioned by Needham is picked up in Dai (1988: 156), where Wang Chong

3E Yi (A.D. 27-97) compares the disturbance of qi by human activity to the way a fish disturbs the

waters in which it swims (see Lun heng ? {jjuan 4, pian 17, 15b-16a in the Sibu Congkan edition.)

The problem is that Dai does not give the context in his quotation, and this makes it quite clear that

the reference is to stimulation of qi in response to the moral qualities of human actions, caoxing

,N IT, just as in the Chunqiufanlu. Wang's point is a clear attack on the position taken by this text,

pointing out that such moral stimulation of qi would be very unlikely to extend as far away as

heaven, just as the disturbance of water by a fish dies away after spreading a few feet. There is no

reference to the human being disturbing the qi mechanically by emitting sound. Dai however

precedes the material about the fish etc. by a sentence pointing to the fact that a man high on a

terrace cannot hear the weak sounds emitted by ants on the ground below. This sentence is

separated from the material quoted on the fish by 164 characters in the original text. It belongs to a

quite different part of Wang's argument (op. cit., 4. 17. 15a) to the effect that heaven is very unlikely

to be able to hear what human beings are saying because it is so far away from them. The only point

that the two sections of text have in common is that they are both part of Wang's general argument

that heaven is unlikely to show any response to anything human beings do. It does seem, therefore,

that Song Yingxing is the first Chinese thinker to make any connexion between the spreading of

water ripples from a point of disturbance and the propagation of disturbance in qi from a source of

sound. Of course such discussions of priority do not in themselves form the proper primary concern

of historians of science. Needham points out (S.C. C., iv, 1, 202) that in Europe Vitruvius had in any

case given the analogy earlier, in the first century B.C.

57 Lun qi, 77. One might have expected to find here the more conventional linkage between the

renal system and the ears; see Sivin (1987: 228). The term liang zhi, literally ' good knowledge' can

be traced back to Mencius (7a, 15) where it refers to knowledge possessed without the exercise of

thought. The term was also used by Zhang Zai (Zhang zi zheng meng zhu, 6, 92), and was central to

the philosophy of Wang Shouren FE - 'f (1472-1529).

58 Lun qi, 78.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

312

CHRISTOPHER CULLEN

affinity for one another. Given the opportunity they will show this

uniting with one another to form qi, which will forthwith in turn r

void from which it came.59

Song argues at length that qi formation requires proper correspondence

between the amounts of water and fire involved: thus if a cup of water is tipped

onto a burning faggot both the water and the fire vanish from sight as they unite

and revert to qi, and hence to the void. For a burning cartload of fuel, however,

a large cauldron of water is needed to match the much greater quantity of fire.

The qi formation process can take place even when fire and water are separated

by a metal or ceramic vessel wall. The relative positions of the two components

are unimportant, but throughout the rule is maintained that each quantity of

water lost to sight requires an equal amount of fire with which to unite. Song

quantifies the amount of fire required in terms which suggest that he is thinking

about the mass of fuel consumed during (as we would now say) the vaporization

of the water.60 Now I have no wish to be thought of as saying anything so

foolish as that Song was aware of or in some way ' anticipated' the concept of

latent heat of vaporization. The figures that Song gives are not necessarily based

on any actual measurement of fuel consumed in boiling away water-although

a rough check suggests they are not unrealistic.61 I would simply like to point

out that Song's theory is one which lends itself easily to quantitative prediction

and measurement. Further, if one carries along Song's line of reasoning one

might ask what happens when the qi produced by the united fire and water

strikes a cold surface. Song is aware (see below) that when this happens the

water reappears as a condensate. Rigorously applied, Song's theory would

therefore predict that the fire should likewise reappear, a prediction that would

be verified by the strong heating effect as condensing steam gives back its latent

heat of vaporization. This is not a point that Song makes, but we should

certainly not be too ready to dismiss the physics of qi and xing as a dead end

incapable of critical development under the right circumstances.

Given Song's idea of fire and water as complementary entities, one naturally

wonders how he explains what is going on during the process of combustion.

One remembers those illustrations in the Tiangong kaiwu of furnaces being

worked to smelting heat by double-action box-bellows (see fig. 1). What does

Song think is going on? In the first place, he thinks of the fuel in the furnace as

being in effect fire in a fixed or solid form. Charcoal, he tells us is solidified fire in

the same way that ice is solidified water, and he appears to regard coal in the

59 Lun qi, 80. In this essay Song speaks of the nature of water and fire in terms which differ

slightly from those in his first essay. In Xingqi hua, they were said to be intermediate in status

between qi and xing, but in the opening of Shuifei sheng huo we are told that qi comes from the void,

qi then forms xing, and xing then differentiates into water and fire. In the rest of the essay however

we commonly find water and fire referred to as qi, or else as forming qi by their union. The reference

to xing seems anomalous.

60 Chinese alchemists had been interested in precise measurements of fuel used as early as the

eighth century A.D. and possibly long before. The aim was to model the supposed sequence of the

cosmic process by, for instance, increasing the amount of fuel fed into the furnace daily in an

arithmetical progression for a number of days, and then reversing the sequence. Such measurements

were however not correlated with any quantitative and empirically determined outcome, such as the

amount of water boiled away; their basis was essentially a priori and numerological. See the

discussion of' fire phasing ', huo hou 9k f? by Nathan Sivin in S.C.C., v, 4, 266-79.

61 The complete combustion of one kg. of coal produces approximately 3 x 107. J of energy, and

one kg. of water at 100?C requires 2 x 106. J to convert it to vapour. According to Song's principle,

each kg. of water vaporized requires 1 kg. of fuel to be burned (quite probably coal in Ming China).

This is possible if the overall efficiency of combustion and heat transfer to the water is of the order of

10%. Given the circumstances of an unlagged pot sitting on a domestic cooking stove such a figure

would not be at all implausible. It may therefore be that Song found that experience appeared to

confirm the 'equal mass' rule that his theory dictated.

This content downloaded from 192.231.40.19 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 08:03:24 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

SONG YINGXING * }, - ON QI ., AND THE WU XING ti jT

313

same way.62 Similarly, although in living wood the amounts of fire and water

present are exactly balanced, dried wood has lost most or all of its water so that

the fire remaining predominates. In such circumstances it only requires a tiny

spark of free fire to nucleate the process of liberation of the fire in the fuel.63

Here again, Song's ideas can be traced back to a starting point in the

thought of Zhang Zai six hundred years earlier. Zhang tells us

Water and fire are qi... earth has no control over them... wood and metal

are respectively the flower and the fruit of earth; in their nature there is a

mingling of water and fire.64

As before however, Song's view is much more concrete and specific than

Zhang's. The presence of water and fire in wood is argued as follows:

If you squeeze a green leaf, a quantity of water may be easily obtained. If

you ignite a dry leaf, a quantity of fire may likewise be easily obtained. The

fact that a tree freshly felled does not ignite when held over a fire is because

the fire and water essences within it cling together and do not separate, and

are not free to abandon their mate to pass to the exterior. But if one heats it

in the rays of the sun, or by the side of a fire, or [exposes it to] a blast of wind,

this will gradually lead the spirit of water to depart back to the void, leaving

the wood ready to ignite. If these drying processes are not of sufficient

strength, one part in ten of the water may remain. This remains pent up and

is the cause of smoke, for the smoke of burning wood is the qi produced as

water and fire struggle to come forth. If the drying process is thorough, then

the wood only retains the substance of fire (huo zhi , ) and in the blazing

clarity [of the flames] any residue of smoke is rapidly transformed.65

But how are the men with the bellows helping matters? Song knew very well

that the blast they supplied was essential if a good blaze was to be maintained.

His explanation depends on the fact that the qi carried in by the blast itself

contains water and fire.66 The water in the blast causes the condensed fire of the

62 Lun qi, 82 on charcoal; compare likewise 59 on coal.

63 Lun qi, 59-60. In Tiangong kaiwu, ch. 1, section 6 (p. 25 in the 1978 edition.) Song tells us that

the flames of the will-o'the-wisp are caused by the release of the fire from rotting wood whose