Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex., 2013)

Загружено:

BrandonАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex., 2013)

Загружено:

BrandonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex.

, 2013)

408 S.W.3d 870

56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177

Andrew M. Williams, Henry L. Burkholder,

Andrew M. Williams & Associates, Bellaire,

Martin R. Nathan, Attorney at

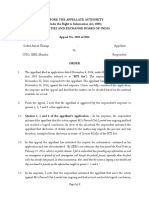

Marc H. NATHAN, Petitioner,

v.

Stephen WHITTINGTON, Respondent.

[408 S.W.3d 872]

No. 120628.

Law, Houston, R. Leonadis McKinney, IV,

Myers Doyle, Houston, TX, for Petitioner.

Supreme Court of Texas.

Eric P. Chenoweth, James E. Zucker,

YetterColeman LLP, Houston, TX, for

Respondent.

Aug. 30, 2013.

Summaries:

Source: Justia

PER CURIAM.

Stephen filed suit against a former business

partner, Evan, in Nevada and prevailed on his

claims. To collect on the judgment, Stephen

filed another suit in Nevada against both

Evan and Marc, alleging that Evan had

fraudulently transferred assets to Marc in

violation of the Nevada Uniform Fraudulent

Transfer Act (Nevada UFTA). The Nevada

court dismissed Stephen's claims, concluding

that it lacked personal jurisdiction over Marc.

Stephen then filed the present suit in a Texas

court under the Texas UFTA (TUFTA),

alleging that Evan had fraudulently

transferred assets to Marc. The trial court

granted summary judgment for Marc,

concluding that TUFTA's four-year statute of

repose extinguished Stephen's claim. The

court of appeals reversed, holding that Tex.

Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code 16.064(a) suspended

the expiration of TUFTA's statute of repose

and allowed Stephen to file this suit within

sixty days after the Nevada court dismissed

the second Nevada suit for lack of personal

jurisdiction. The Supreme Court reversed,

holding that because the TUFTA provision

that extinguished Stephen's claim was a

statute of repose, and section 16.064 applies

only to statutes of limitations, section 16.064

did not save or revive Stephen's claim.

We must decide in this case whether a

statute that suspends the running of a

statute of limitations applies to a statute of

repose that otherwise extinguishes the

plaintiff's cause of action. The trial court held

that it does not and granted the defendant's

motion for summary judgment. The court of

appeals, with one justice dissenting, held that

it does and reversed. We hold that the

suspension statute does not apply to a statute

of repose, so we reverse the judgment of the

court of appeals and reinstate the trial court's

summary judgment.

Stephen Whittington initially filed suit in

Nevada and prevailed on his claims against a

former business partner, Evan Baergen. To

collect on the judgment, he then filed another

suit in Nevada, against both Baergen and

Marc Nathan, the petitioner in the present

case. In the second suit, Whittington alleged

that Baergen had fraudulently transferred

assets to Nathan in violation of the Nevada

Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act (Nevada

UFTA). Whittington filed the second suit in

May 2008, just under four years after the date

he alleged the fraudulent transfer occurred in

May 2004. Six months later, in November

2008, the Nevada court held that it lacked

personal jurisdiction over Nathan and

dismissed Whittington's claims. Less than

sixty days later, in January 2009, Whittington

[408 S.W.3d 871]

-1-

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex., 2013)

filed the present suit, in a Texas court, under

the Texas UFTA (TUFTA), again alleging that

Baergen had fraudulently transferred assets

to Nathan. Nathan moved for summary

judgment, arguing that TUFTA's four-year

statute of repose extinguished Whittington's

claim. SeeTex. Bus. & Com.Code

24.010(a)(1) (1993). The trial court agreed

and granted Nathan's motion for summary

judgment.

a cause of action with respect to a

fraudulent transfer or obligation under this

chapter is extinguished unless action is

brought ... within four years after the transfer

was made or the obligation was

[408 S.W.3d 873]

incurred or, if later, within one year after the

transfer or obligation was or could reasonably

have been discovered by the claimant.

Whittington appealed, and the court of

appeals reversed and remanded. The majority

held that section 16.064(a) of the Texas Civil

Practice & Remedies Code suspended the

expiration of TUFTA's statute of repose and

allowed Whittington to file this new suit

within sixty days after the Nevada court

dismissed the second Nevada suit for lack of

jurisdiction. Whittington v. Nathan, 371

S.W.3d 399, 403 (Tex.App.Houston [1st

Dist.] 2012). One justice dissented, on the

ground that section 16.064(a) suspends the

running of a statute of limitations, not of a

statute of repose like the TUFTA provision

that extinguished Whittington's claim. Id.

(Brown, J., dissenting).

Tex. Bus. & Com.Code 24.010(a)(1). The

parties and the court of appeals all agreed

that this provision is a statute of repose,

rather than a statute of limitations. [W]hile

statutes of limitations operate procedurally to

bar the enforcement of a right, a statute of

repose takes away the right altogether,

creating a substantive right to be free of

liability after a specified time. Methodist

Healthcare Sys. of San Antonio, Ltd. v.

Rankin, 307 S.W.3d 283, 287 (Tex.2010)

(quoting Galbraith Eng'g Consultants, Inc. v.

Pochucha, 290 S.W.3d 863, 866 (Tex.2009)).

Statutes of repose are of an absolute nature,

and their key purpose ... is to eliminate

uncertainties under the related statute of

limitations and to create a final deadline for

filing suit that is not subject to any

exceptions, except perhaps those clear

exceptions in the statute itself. Id. at 286

87. Unlike statutes of limitations, which are

intended primarily to encourage diligence on

the part of plaintiffs, statutes of repose may

serve other purposes and may run from some

event other than when the cause of action

accrued. See Nelson v. Krusen, 678 S.W.2d

918, 926 (Tex.1984) (Robertson, J.,

concurring).

We review the trial court's summary

judgment de novo. Travelers Ins. Co. v.

Joachim, 315 S.W.3d 860, 862 (Tex.2010). To

resolve this case, we must construe both

TUFTA's section 24.010 and section

16.064(a) of the Civil Practice & Remedies

Code. We also review issues of statutory

construction de novo. Loaisiga v. Cerda, 379

S.W.3d 248, 25455 (Tex.2012). Our

objective is to give effect to the Legislature's

intent, and we do that by applying the

statutes' words according to their plain and

common meaning unless a contrary intention

is apparent from the statutes' context.

Molinet v. Kimbrell, 356 S.W.3d 407, 411

(Tex.2011).

Although we have not previously

addressed this issue, other Texas courts have,

and like the parties and the court of appeals

in this case, they have agreed that the

provision is a statute of repose. See Janvey v.

Democratic Senatorial Campaign Comm.,

In TUFTA section 24.010, entitled

Extinguishment Of Cause Of Action, the

Legislature has provided that

-2-

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex., 2013)

793 F.Supp.2d 825, 83031 n. 5

(N.D.Tex.2011) (citing cases and stating the

few Texas intermediate appellate courts to

expressly consider the matter view the timebar provision as a statute of repose); see also

Zenner v. Lone Star Striping & Paving,

L.L.C., 371 S.W.3d 311, 315 n. 1 (Tex.App.

Houston [1st Dist.] 2012, pet. denied)

(Entitled Extinguishment of Cause of

Action, section 24.0010[sic] is a statute of

repose, rather than a statute of limitations.).

In the absence of any uniformity among

the other states, we have also considered the

comments of the National Conference of

Commissioners on Uniform State Laws,

which promulgated the model UFTA. We note

first that their Prefatory Notes to the model

UFTA also refer to the provision as a statute

of limitations. Unif. Fraudulent Transfer Act,

7A pt.II U.L.A. 7 (2006) (Prefatory Note)

(The new Act also includes a statute of

limitations that bars the right rather than the

remedy on expiration of the statutory periods

prescribed.). Because of this, a Pennsylvania

intermediate appellate court decided to label

the provision as a statute of limitations, even

though it recognized that [t]he language of

the

provision,

which

involves

the

extinguishment of a cause of action rather

than a limitation on the action, would appear

to be labeled properly as a statute of repose.

KB Bldg. Co., 833 A.2d at 1133 n. 1.

But TUFTA is a uniform act, so its

provisions must be applied and construed to

effectuate its general purpose to make

uniform the law with respect to the subject of

this chapter among states enacting it. Tex.

Bus. & Com.Code 24.012. We will therefore

independently review the issue, to ensure that

our construction of section 24.010 is as

consistent as possible with the constructions

of other states that have enacted a Uniform

Fraudulent Transfer Act containing a similar

provision.

Considering the actual language of

TUFTA

section

24.010

and

the

Commissioners' comments to UFTA section 9

on which it is modeled, we agree with the

parties and the court of appeals in this case

that it is a statute of repose, rather than a

statute of limitations. By its own terms, the

provision does not just procedurally bar an

untimely

claim,

it

substantively

extinguishes the cause of action. As the

Commissioners' Prefatory Note explains

(despite its reference to a statute of

limitations), the provision bars the right

rather than the remedy on expiration of the

statutory periods prescribed. Unif.

Fraudulent Transfer Act, 7A pt.II U.L.A. 7

(2006)

(Prefatory

Note).

And

the

Commissioners' comments to section 9

explain that [i]ts purpose is to make clear

that lapse of the statutory periods prescribed

by the section bars the right and not merely

the remedy. Id. at 195, 9 cmt. 1. This

language is nearly identical to our definition

of a statute of repose. See Rankin, 307 S.W.3d

at 287 ([W]hile statutes of limitations

operate procedurally to bar the enforcement

of a right, a statute of repose takes away the

We have found that some courts,

including the high courts of several states,

have referred to this UFTA provision as a

statute of limitations, 1 while others have

referred to it as a statute of repose. 2See K

B Bldg. Co. v. Sheesley Constr., Inc., 833 A.2d

1132, 1133 n. 1 (Pa.Super.Ct.2003)

[408 S.W.3d 874]

(noting that its review of decisions of other

jurisdictions reveals that [the provision] is

referred to as both a statute of limitations and

a statute of repose). But in most of the

opinions in which the court referred to the

provision as a statute of limitations, including

all of those of the states' high courts, the

courts did not actually consider or address

the issue. Instead, they simply referred to the

provision as a statute of limitations without

actually concluding that it was a statute of

limitations as opposed to a statute of repose.

-3-

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex., 2013)

right altogether, creating a substantive right

to be free of liability after a specified time.

(quoting Galbraith, 290 S.W.3d at 866)).

Unlike a statute of limitations, the provision

extinguishes the underlying cause of action.

We do not perceive strong uniformity among

the states in their interpretation of this

provision, and we see no need to compromise

the statute of repose jurisprudence of cases

like Galbraith and Rankin to follow states

that have merely referred to the provision as a

statute of limitations without actually

deciding the issue.

By its own terms, section 16.064(a)

applies only to a statute of limitations. In

Galbraith, we interpreted a similar statute,

which (at that time) provided that a plaintiff

who joins a responsible third party as a

defendant is not barred by limitations. 290

S.W.3d at 86566 (construing former Tex.

Pra C. & Rem.Code 33.004(e)).3 We

acknowledged that, generally, the term

limitations could refer to the restrictions

that both statutes of limitations and statutes

of repose impose, but we held that former

section 33.004(e) applied only to statutes of

limitations, and not to a statute of repose. Id.

at 869. As we explained, [b]ecause

application of the revival statute in this

instance effectively renders the period of

repose indefinite, a consequence clearly

incompatible with the purpose for such

statutes, we conclude that the Legislature

intended for the term limitations' in section

33.004(e) to refer only to statutes of

limitations. Id.

In addition to agreeing that the TUFTA

provision is a statute of repose, the parties

also agree that, unless section 16.064(a)

applies, the statute of repose extinguished

Whittington's claim before he filed this suit.

In section 16.064, entitled Effect Of Lack Of

Jurisdiction, the Legislature has suspended

the running of a statute of limitations for

sixty days, if a trial court dismisses a claim for

lack of jurisdiction:

Applying section 16.064 to TUFTA's

statute of repose would raise the same

concern we identified in Galbraith: because a

trial court may dismiss a case for lack of

jurisdiction long after the statute of repose

extinguishes the cause of action, application

of section 16.064 would frustrate the certainty

that the statute of repose provides. Like the

designation of a responsible third party in

another lawsuit, the final dismissal of another

lawsuit may come months or years' after the

statute of repose deadline. Whittington, 371

S.W.3d at 407 (Brown, J., dissenting) (citing

Galbraith, 290 S.W.3d at 867). It is true that

under section 16.064, unlike under former

section 33.004 in Galbraith, the plaintiff

must bring suit (albeit in the wrong court)

before the limitations period expires. But if

section 16.064 applies to the TUFTA statute

of repose, the defendant does not know if the

suit will be dismissed, or if it will later be

refiled in another court (even after the statute

has extinguished the cause of action), or if it

will proceed in the original court.

(a) The period between the date of filing

an action in a trial court and the date of a

second filing of the same action in a different

court suspends

[408 S.W.3d 875]

the running of the applicable statute of

limitations for the period if:

(1) because of lack of jurisdiction in the

trial court where the action was first filed, the

action is dismissed or the judgment is set

aside or annulled in a direct proceeding; and

(2) not later than the 60th day after the

date the dismissal or other disposition

becomes final, the action is commenced in a

court of proper jurisdiction.

Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem.Code 16.064(a)

(1985).

-4-

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex., 2013)

As we have said before, statutes of

repose are of an absolute nature and address

concerns beyond the certainty of the litigants:

Because TUFTA's section 24.010 is a

statute of repose, and section 16.064 applies

only to statutes of limitations, the latter does

not save or revive Whittington's claim.

Accordingly, without hearing oral argument,

Tex.R.App. P. 59. 1, we grant Nathan's

petition for review, reverse the court of

appeals' judgment, and reinstate the trial

court's judgment of dismissal.

The

Legislature

could

reasonably

conclude that the general welfare of society,

and various trades and professions that serve

society, are best served with statutes of repose

that do not submit to exceptions even if a

small number of claims are barred through no

fault of the plaintiff, since the purpose of a

statute of repose is to provide absolute

protection to certain parties from the burden

of indefinite potential liability. The whole

point of layering a statute of repose over the

statute of limitations is to fix an outer limit

beyond which no action can be maintained.

One practical

-------Notes:

1.See

Peacock Timber Transp., Inc. v. B.P.

Holdings, LLC, 115 So.3d 914, 91920

(Ala.2012); Kobritz v. Severance, 912 A.2d

1237, 1241 n. 3 (Me.2007); Cavadi v. DeYeso,

458 Mass. 615, 941 N.E.2d 23, 26 (2011); Gulf

Ins. Co. v. Clark, 304 Mont. 264, 20 P.3d

780, 782 (2001); Norwood Grp., Inc. v.

Phillips, 149 N.H. 722, 828 A.2d 300, 303

(2003); SASCO 1997 NI, LLC v. Zudkewich,

166 N.J. 579, 767 A.2d 469, 47173 (2001);

Investors Title Ins. Co. v. Herzig, 785 N.W.2d

863, 877 (N.D.2010); Duffy v. Dwyer, 847

A.2d 266, 26971 (R.I.2004); State ex rel.

Dep't of Revenue v. Karras, 515 N.W.2d 248,

249 (S.D.1994); Freitag v. McGhie, 133

Wash.2d 816, 947 P.2d 1186, 1188 (1997).

[408 S.W.3d 876]

upside of curbing open-ended exposure is to

prevent defendants from answering claims

where evidence may prove elusive due to

unavailable witnesses (perhaps deceased),

faded memories, lost or destroyed records,

and institutions that no longer exist.

Rankin, 307

omitted).

S.W.3d

at

287

(citations

We acknowledge that TUFTA's statute of

repose may work an inequitable hardship on

Whittington in this case. Whittington brought

a timely UFTA claim in Nevada, and he refiled

the claim in Texas within sixty days after the

Nevada court dismissed it for lack of

jurisdiction. But the Legislature has balanced

this hardship against the benefits of the

certainty that a statute of repose provides by

extinguishing claims upon a specific deadline.

The task of balancing these equities belongs

to the Legislature, not to this Court. As we

have noted, the Legislature has chosen to

suspend the running of statutes of limitations,

not of statutes of repose.

2.See

LaRosa v. LaRosa, 482 Fed.Appx.

750, 753 (4th Cir.2012); Klein v. Capital One

Fin. Corp., No. 4:10CV00629EJL, 2011

WL 3270438, at *78, *7 n. 5 (D.Idaho July

29, 2011) (mem.op.); Moore v. Browning,

203 Ariz. 102, 50 P.3d 852, 85859

(Ct.App.2002); First Sw. Fin. Servs. v.

Pulliam, 121 N.M. 436, 912 P.2d 828, 830

(Ct.App.1996).

3.See

Act of May 4, 1995, 74th Leg., R.S.,

ch. 136, 1995 Tex. Gen. Laws 97273,

amended by Act of June 2, 2003, 78th Leg.,

R.S., ch. 204, 4.04, sec. 33.004(e), 2003

Tex. Gen. Laws 85556, repealed by Act of

-5-

Nathan v. Whittington, 408 S.W.3d 870, 56 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 1177 (Tex., 2013)

May 24, 2011, 82d Leg., R.S., ch. 203, 5.02,

sec. 33.004(e), 2011 Tex. Gen. Laws 759.

-6-

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Philippine Administrative Law ReviewerДокумент170 страницPhilippine Administrative Law ReviewerIcee Genio95% (41)

- RCBC v. Alta RTW Credit Transactions RulingДокумент2 страницыRCBC v. Alta RTW Credit Transactions RulingPau SaulОценок пока нет

- Death Penalty Trial Opening Statements: Trial TranscriptsДокумент47 страницDeath Penalty Trial Opening Statements: Trial TranscriptsReba Kennedy100% (2)

- Miller V 24 Hour Fitness USAДокумент8 страницMiller V 24 Hour Fitness USABrandonОценок пока нет

- Acain Vs IACДокумент1 страницаAcain Vs IACSam FajardoОценок пока нет

- Ramirez vs. Corpuz - MacandogДокумент11 страницRamirez vs. Corpuz - MacandogAdrianne BenignoОценок пока нет

- Intramuros Tennis Club, Inc. vs. Philippine Tourism AuthorityДокумент16 страницIntramuros Tennis Club, Inc. vs. Philippine Tourism Authorityvince005Оценок пока нет

- Legal Ethics 2017Документ188 страницLegal Ethics 2017Fai Meile100% (1)

- Case 12 Ang Yu Asuncion Vs CAДокумент1 страницаCase 12 Ang Yu Asuncion Vs CAAnonymous MhXTwMP2100% (1)

- Qna-Compilation BoardДокумент168 страницQna-Compilation BoardAngel King Relatives100% (2)

- Quiros V Wal-MartДокумент10 страницQuiros V Wal-MartBrandonОценок пока нет

- Hileman V Rouse PropertiesДокумент27 страницHileman V Rouse PropertiesBrandonОценок пока нет

- Brown v. City of Houston, - 337 f.3d 539 (2003) - 7f3d5391825Документ5 страницBrown v. City of Houston, - 337 f.3d 539 (2003) - 7f3d5391825BrandonОценок пока нет

- Allen v. Wal-Mart Stores - No. Civ. A. H-14-3628. - 20150501n05Документ7 страницAllen v. Wal-Mart Stores - No. Civ. A. H-14-3628. - 20150501n05BrandonОценок пока нет

- Mccarty v. Hillstone Rest - Civil Action No. 3... - 20151116e05Документ6 страницMccarty v. Hillstone Rest - Civil Action No. 3... - 20151116e05BrandonОценок пока нет

- THOMPSON v. BANK OF AMERI - 783 F.3d 1022 (2015) - 20150421157Документ6 страницTHOMPSON v. BANK OF AMERI - 783 F.3d 1022 (2015) - 20150421157BrandonОценок пока нет

- U.S. EX REL. FARMER v. CI - 523 F.3d 333 (2008) - 3f3d3331827Документ10 страницU.S. EX REL. FARMER v. CI - 523 F.3d 333 (2008) - 3f3d3331827BrandonОценок пока нет

- Gaines V. EG & G TechДокумент6 страницGaines V. EG & G TechBrandonОценок пока нет

- Wyatt v. Hunt Plywood Co. - 297 f.3d 405 (2002) - 7f3d4051666Документ9 страницWyatt v. Hunt Plywood Co. - 297 f.3d 405 (2002) - 7f3d4051666BrandonОценок пока нет

- Arsement V. Spinnaker Exploration Co., LLC: Cited Cases Citing CaseДокумент11 страницArsement V. Spinnaker Exploration Co., LLC: Cited Cases Citing CaseBrandonОценок пока нет

- Britton v. Home Depot U.S - 181 F.supp.3d 365 (2016) - 70227000148Документ5 страницBritton v. Home Depot U.S - 181 F.supp.3d 365 (2016) - 70227000148BrandonОценок пока нет

- Simpson v. Orange County - No. 09-18-00240-Cv. - 20190207578Документ6 страницSimpson v. Orange County - No. 09-18-00240-Cv. - 20190207578BrandonОценок пока нет

- TIG INS. CO. v. SEDGWICK - 276 F.3d 754 (2002) - 6f3d7541935Документ7 страницTIG INS. CO. v. SEDGWICK - 276 F.3d 754 (2002) - 6f3d7541935BrandonОценок пока нет

- Hughes v. Kroger Texas L. - No. 3 - 15-Cv-0806-m... - 20160308e07Документ5 страницHughes v. Kroger Texas L. - No. 3 - 15-Cv-0806-m... - 20160308e07BrandonОценок пока нет

- MARTIN v. CHICK-FIL-A, HW - No. 14-13-00025-CV. - 20140205646Документ6 страницMARTIN v. CHICK-FIL-A, HW - No. 14-13-00025-CV. - 20140205646BrandonОценок пока нет

- GARCIA v. WAL-MART STORES - 893 F.3d 278 (2018) - 20180618091Документ5 страницGARCIA v. WAL-MART STORES - 893 F.3d 278 (2018) - 20180618091BrandonОценок пока нет

- Reyes v. Dollar Tree Stor - 221 F.supp.3d 817 (2016) - 70906003049Документ11 страницReyes v. Dollar Tree Stor - 221 F.supp.3d 817 (2016) - 70906003049BrandonОценок пока нет

- Reeves v. Sanderson Plumbing Products, Inc. - FindlawДокумент9 страницReeves v. Sanderson Plumbing Products, Inc. - FindlawBrandonОценок пока нет

- Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc. - FindlawДокумент12 страницAnderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc. - FindlawBrandonОценок пока нет

- Parker v. Highland Park, Inc., 565 S.W.2d 512 (Tex., 1978)Документ10 страницParker v. Highland Park, Inc., 565 S.W.2d 512 (Tex., 1978)BrandonОценок пока нет

- Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Reece, 81 S.W.3d 812 (Tex., 2002)Документ5 страницWal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Reece, 81 S.W.3d 812 (Tex., 2002)BrandonОценок пока нет

- Mangham v. YMCA of Austin, 408 S.W.3d 923 (Tex. App., 2013)Документ7 страницMangham v. YMCA of Austin, 408 S.W.3d 923 (Tex. App., 2013)BrandonОценок пока нет

- Thoreson v. Thompson, 431 S.W.2d 341 (Tex., 1968)Документ6 страницThoreson v. Thompson, 431 S.W.2d 341 (Tex., 1968)BrandonОценок пока нет

- Occidental Chem. Corp. v. Jenkins, 478 S.W.3d 640 (Tex., 2016)Документ9 страницOccidental Chem. Corp. v. Jenkins, 478 S.W.3d 640 (Tex., 2016)BrandonОценок пока нет

- Gannett Outdoor Co. of Texas v. Kubeczka, 710 S.W.2d 79 (Tex. App., 1986)Документ10 страницGannett Outdoor Co. of Texas v. Kubeczka, 710 S.W.2d 79 (Tex. App., 1986)BrandonОценок пока нет

- Seideneck v. Cal Bayreuther Associates, 451 S.W.2d 752 (Tex., 1970)Документ5 страницSeideneck v. Cal Bayreuther Associates, 451 S.W.2d 752 (Tex., 1970)BrandonОценок пока нет

- McDaniel v. Cont'l Apartments Joint VentureДокумент7 страницMcDaniel v. Cont'l Apartments Joint VentureBrandonОценок пока нет

- Keetch v. Kroger Co., 845 S.W.2d 262 (Tex., 1992)Документ12 страницKeetch v. Kroger Co., 845 S.W.2d 262 (Tex., 1992)BrandonОценок пока нет

- H.E. Butt Grocery Co. v. Warner, 845 S.W.2d 258 (Tex., 1992)Документ6 страницH.E. Butt Grocery Co. v. Warner, 845 S.W.2d 258 (Tex., 1992)BrandonОценок пока нет

- Javier vs. de GuzmanДокумент5 страницJavier vs. de GuzmanAnonymous oDPxEkdОценок пока нет

- 57 Simangan Vs PeopleДокумент12 страниц57 Simangan Vs PeopleFraulein G. ForondaОценок пока нет

- 09-02-20 Galdjie V Darwish (SC052737) - Declaration of Barabara Kramar Darwish SДокумент6 страниц09-02-20 Galdjie V Darwish (SC052737) - Declaration of Barabara Kramar Darwish SHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)Оценок пока нет

- People Vs ListerioДокумент3 страницыPeople Vs ListerioDave UmeranОценок пока нет

- Court Suspends Lawyer for Mishandling Criminal CaseДокумент77 страницCourt Suspends Lawyer for Mishandling Criminal CaseCharls BagunuОценок пока нет

- Appeal No. 2588 of 2016 Filed by Mr. Gokul Ashok Thampi.Документ3 страницыAppeal No. 2588 of 2016 Filed by Mr. Gokul Ashok Thampi.Shyam SunderОценок пока нет

- Sanson vs. CA (2003)Документ10 страницSanson vs. CA (2003)Cherith MonteroОценок пока нет

- United States v. Levinne McNeill, 4th Cir. (2016)Документ3 страницыUnited States v. Levinne McNeill, 4th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States Bankruptcy Court Central District of California Riverside DivisionДокумент4 страницыUnited States Bankruptcy Court Central District of California Riverside DivisionChapter 11 DocketsОценок пока нет

- Luzvenia Cortina, A046 870 073 (BIA Sept. 4, 2015)Документ9 страницLuzvenia Cortina, A046 870 073 (BIA Sept. 4, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCОценок пока нет

- United States v. Alex Daniel Millar, 543 F.2d 1280, 10th Cir. (1976)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Alex Daniel Millar, 543 F.2d 1280, 10th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Coffee Exchange, 263 U.S. 611 (1924)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Coffee Exchange, 263 U.S. 611 (1924)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Criminal Appeal Case on Further InvestigationДокумент4 страницыCriminal Appeal Case on Further Investigationjack_dorsey3821100% (1)

- DSNLU: Sunil Krishna Paul vs Commissioner of Income-TaxДокумент6 страницDSNLU: Sunil Krishna Paul vs Commissioner of Income-TaxKamlakar ReddyОценок пока нет

- United States v. Vincent Maurice Johnson, 989 F.2d 496, 4th Cir. (1993)Документ4 страницыUnited States v. Vincent Maurice Johnson, 989 F.2d 496, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Crismina Garments v. CAДокумент1 страницаCrismina Garments v. CARitzchalle Garcia-OalinОценок пока нет

- Case LawДокумент10 страницCase LawAnkitОценок пока нет

- Hon Ne Chan V Honda MotorsДокумент4 страницыHon Ne Chan V Honda MotorsDenise DianeОценок пока нет

- Judgment Chbihi Loudoudi and Others v. Belgium Refusal To Grant Adoption of A Child in Kafala CareДокумент4 страницыJudgment Chbihi Loudoudi and Others v. Belgium Refusal To Grant Adoption of A Child in Kafala CareFelicia FeliciaОценок пока нет

- 12 13 11 0204 2064 22176 Motion For New Trial, Notice of Appeal NRS 189.030 (1) Requires RMC Add To ROA in CR11-2064 RMC Deficiencies Opt A9Документ901 страница12 13 11 0204 2064 22176 Motion For New Trial, Notice of Appeal NRS 189.030 (1) Requires RMC Add To ROA in CR11-2064 RMC Deficiencies Opt A9NevadaGadflyОценок пока нет

- Benguet Corp V CBAA PDFДокумент8 страницBenguet Corp V CBAA PDFStella LynОценок пока нет