Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Jama Howell 2017 Gs 170001

Загружено:

Sergio Daniel Chumacero SánchezОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jama Howell 2017 Gs 170001

Загружено:

Sergio Daniel Chumacero SánchezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Clinical Review & Education

JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis

Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock

Michael D. Howell, MD, MPH; Andrew M. Davis, MD, MPH

GUIDELINE TITLE Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International

Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock:

2016

DEVELOPERS Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC), Society of

Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and European Society of

Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM)

RELEASE DATE January 18, 2017

PRIOR VERSIONS 2012, 2008, 2004

TARGET POPULATION Adults with sepsis or septic shock

Antibiotic stewardship: Assess patients daily for deescalation

of antimicrobials; narrow therapy based on cultures and/or

clinical improvement (BPS).

Managing resuscitation:

Fluids: For patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion, provide

30mL/kgofintravenouscrystalloidwithin3hours(strongrecommendation; low QOE) with additional fluid based on frequent

reassessment (BPS), preferentially using dynamic variables to

assess fluid responsiveness (weak recommendation; low QOE).

Resuscitation targets: For patients with septic shock requiring

vasopressors, target a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of

65 mm Hg (strong recommendation; moderate QOE).

Vasopressors: Use norepinephrine as a first-choice

vasopressor (strong recommendation; moderate QOE).

SELECTED MAJOR RECOMMENDATIONS

Mechanical ventilation in patients with sepsis-related ARDS:

Managing infection:

Antibiotics: Administer broad-spectrum intravenous

antimicrobials for all likely pathogens within 1 hour after

sepsis recognition (strong recommendation; moderate

quality of evidence [QOE]).

Source control: Obtain anatomic source control as rapidly

as is practical (best practice statement [BPS]).

Summary of the Clinical Problem

Sepsis results when the bodys response to infection causes lifethreatening organ dysfunction. Septic shock is sepsis that results in

tissue hypoperfusion, with vasopressor-requiring hypotension and

elevated lactate levels.1 Sepsis is

a leading cause of death, morViewpoint

bidity, and expense, contributing to one-third to half of deaths of hospitalized patients,2 depending on definitions.3 Management of sepsis is a complicated clinical

challenge requiring early recognition and management of infection, hemodynamic issues, and other organ dysfunctions.

Target a tidal volume of 6 mL/kg of predicted body weight

(strong recommendation; high QOE) and a plateau pressure

of 30 cm H2O (strong recommendation; moderate QOE).

Formal improvement programs:

Hospitals and health systems should implement programs to

improve sepsis care that include sepsis screening (BPS).

fessional librarians assisted with evidence reviews. Although the 2016

revision of definitions for sepsis were published during the guideline development process,1 studies used for guideline evidence used

earlier definitions of sepsis syndromes.

Benefits and Harms

The 2012 sepsis guidelines strongly recommended protocolized resuscitation with quantitative end points (early goal-directed therapy

[EGDT]). Recommendations included specific goals for central venous pressure (CVP), MAP, and central venous oxygen saturation and

formed the basis of national quality and performance metrics.5

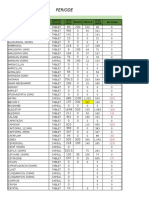

Table. Guideline Rating

Characteristics of the Guideline Source

The guideline was developed by the SSC, with funding and governance from the SCCM and the ESICM (Table).4 More than 30 additional organizations endorsed the guidelines. Guideline committee

members were from numerous specialties and included methods

experts and a patient representative. A formal conflict of interest

management policy was followed.

Standard

Establishing transparency

Management of conflict of interest in the guideline

development group

Guideline development group composition

Clinical practice guidelinesystematic review intersection

Establishing evidence foundations and rating strength

for each of the guideline recommendations

Articulation of recommendations

Rating

Good

Good

Evidence Base

External review

Updating

Fair

Fair

Implementation issues

Fair

The guideline committee used the GRADE method. Population, intervention, control, and outcomes questions were constructed; projama.com

Good

Good

Good

Fair

(Reprinted) JAMA Published online January 19, 2017

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/0/ on 01/23/2017

E1

Clinical Review & Education JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis

Since the 2012 guideline, substantial evolution has occurred in understandingthevalueofEGDT.Threekeyrandomizedtrialsenrolledpatients presenting to the emergency department who had sepsis with

shock or hypoperfusion. In the PROCESS trial (n=1341 patients from 31

US institutions), protocol-based approaches did not reduce 60-day

mortality vs usual care (19.5% vs 18.9%; relative risk [RR], 1.04; 95% CI,

0.82-1.31;P=.83).6 ThesimilarlysizedUK-basedPROMISE7 andtheARISE

trial8 from Australia and New Zealand both compared EGDT and usual

care at 90 days and again found no difference in mortality (29.5% vs.

29.2%;RR,1.01;95%CI,0.85-1.20;P=.90and18.6%vs18.8%;RR,0.98;

95%CI,0.80-1.21;P=.90,respectively).Takentogether,thesetrialssuggest that while EGDT is safe, it is not superior to usual, nonprotocolized

care. Usual care has also evolved since these trials to include more aggressive fluid resuscitation.9 In response, the 2016 guideline has removedstandardEGDTresuscitationtargets,insteadrecommendingthat

sepsis-induced hypoperfusion be treated with at least 30 mL/kg of intravenous crystalloid given in 3 hours or less. The authors note that

sparsecontrolleddatasupportthisvolumebutitsdeliveryallowsresuscitation to begin during evaluation. In the absence of the former static

EGDT targets (eg, CVP), the guideline emphasizes frequent clinical reassessment and the use of dynamic measures of fluid responsiveness

(eg,arterialpulsepressurevariation),givenevidencethatdynamicmeasures predict fluid responsiveness better than static measures do.

Because infection causes sepsis, managing infection is perhaps the most critical component of sepsis therapy. Mortality increases even with very short delays of antimicrobials. To optimize

the risk-benefit profile, the strategy of initial broad-spectrum therapy

requires meticulous attention to antimicrobial stewardship, including early appropriate cultures and daily review to reduce or stop antimicrobials. Additionally, anatomic source control (eg, identifying

infected central lines, pyelonephritis with ureteral obstruction, intestinal perforation) should occur as soon as is practical.

nitions for sepsis,1 the guideline provides strong recommendations

for a number of elements of standardized care, such as antimicrobial therapy, initial fluid volume, blood pressure goals, and vasopressor choice. Reflecting substantial consensus among experts, voting was by 75% of panel members with at least 80% agreement.

The guideline also provides a BPS for hospitals and health systems to develop formal sepsis performance improvement programs, given a suggestion of a mortality benefit. The recent NICE

guidelines include tips on patient populations at higher risk of sepsis,

clinical presentations, and initial laboratories for diagnosis and risk

stratification. Tools such as order sets, checklists, posters, reminder

cards, and electronic medical record decision support may assist clinicians in early recognition and appropriate treatment of sepsis.10

Pediatric sepsis guidelines will be published separately, with a

specific guideline for ventilation in ARDS expected in 2017.

Areas in Need of Future Study or Ongoing Research

The best approach for hemodynamic therapy for sepsis has become more uncertain as evidence has accumulated. This extends

even to the degree to which clinicians should use intravenous fluids as a foundation for resuscitation in some patient groups. The

guideline correctly identifies this as a key area for further research.

The best way to improve public health related to sepsis also

remains unsettled. For example, most US hospitals are required to report sepsis process measures. Collection of these data may be

resource intense and may distract from other improvement efforts,5

inadvertently promote overtreatment or unnecessary testing, or delay nonsepsis diagnoses.3 At present, the international consensus definition of sepsis,1 the new guidelines,4 and CMSs core measure requirements are unsynchronized. Thoughtful alignment is in order to ensure

meaningful reporting and improve patient outcomes.

Related Guidelines and Other Resources

Discussion

The PROCESS,6 PROMISE,7 and ARISE8 trials have created substantial uncertainty in how to guide clinicians managing patients with sepsis and septic shock.9 When usual care is equivalent to EGDT, what

is a clinician to do? The most significant update to the guideline reflects this shift in evidence: removing most specific EGDT end points

and emphasizing frequent reevaluation and patient-specific tailoring of hemodynamic therapy. Even with a change in consensus defi-

Surgical Infection Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America

(abdominal infections)

Infectious Diseases Society of America and American Thoracic

Society (ventilator-associated pneumonia)

Surviving Sepsis Campaign

ARTICLE INFORMATION

REFERENCES

Author Affiliations: Center for Healthcare Delivery

Science and Innovation, University of Chicago,

Chicago, Illinois (Howell); Pulmonary and Critical

Care, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

(Howell); General Internal Medicine, University of

Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Davis).

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al.

The Third International Consensus Definitions for

Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315

(8):801-810.

Corresponding Author: Michael D. Howell, MD,

MPH, University of Chicago, 850 E 58th St,

Chicago, IL 60615 (mdh@uchicago.edu).

Published Online: January 19, 2017.

doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0131

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have

completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Dr Howell reports royalties from UpToDate and

anticipated royalties from McGraw-Hill. No other

disclosures were reported.

E2

UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

2. Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital

deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent

cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312(1):90-92.

6. Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT, et al.

A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early

septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1683-1693.

7. Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Trial of

early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock.

N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1301-1311.

8. Peake SL, Delaney A, Bailey M, et al.

Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early

septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1496-1506.

3. Rhee C, Gohil S, Klompas M. Regulatory

mandates for sepsis carereasons for caution.

N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1673-1676.

9. Levy MM. Early goal-directed therapy: what do

we do now? Crit Care. 2014;18(6):705.

4. Rhodes A, Evans L, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving

Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for

management of sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care

Med. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255

10. Damiani E, Donati A, Serafini G, et al. Effect of

performance improvement programs on

compliance with sepsis bundles and mortality. PLoS

One. 2015;10(5):e0125827.

5. Wall MJ, Howell MD. Variation and

cost-effectiveness of quality measurement

programs. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1597-1599.

JAMA Published online January 19, 2017 (Reprinted)

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/0/ on 01/23/2017

jama.com

Вам также может понравиться

- Common Sense Approach To Managing SepsisДокумент12 страницCommon Sense Approach To Managing SepsiszepedrocorreiaОценок пока нет

- Top Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyОт EverandTop Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (7)

- Advances in The Management of Pediatric Septic Shock: Old Questions, New AnswersДокумент7 страницAdvances in The Management of Pediatric Septic Shock: Old Questions, New AnswersSandip KumarОценок пока нет

- CAP in AdultsДокумент46 страницCAP in AdultsEstephany Velasquez CalderonОценок пока нет

- Hemodynamic Support in The Early Phase of Septic ShockДокумент12 страницHemodynamic Support in The Early Phase of Septic ShockGiancarlo AgüeroОценок пока нет

- IDSA-ATS - Consensus Guidelines On The Management of CAP in AdultsДокумент46 страницIDSA-ATS - Consensus Guidelines On The Management of CAP in AdultscharliedelОценок пока нет

- Osborn 2017Документ22 страницыOsborn 2017uci 2Оценок пока нет

- Guias Neumonia Idsa AtsДокумент46 страницGuias Neumonia Idsa AtsAleksVaReОценок пока нет

- Silversides2017 Article ConservativeFluidManagementOrDДокумент18 страницSilversides2017 Article ConservativeFluidManagementOrDDillaОценок пока нет

- Albumin in aSAH NeuroCrit2023Документ11 страницAlbumin in aSAH NeuroCrit2023Ahida VelazquezОценок пока нет

- Practice ParametersДокумент48 страницPractice Parametersmisbah_mdОценок пока нет

- Am J Crit Care 2013 Kleinpell 212-22-2Документ12 страницAm J Crit Care 2013 Kleinpell 212-22-2Helmy HanafiОценок пока нет

- Surviving Sepsis: Going Beyond The Guidelines: Review Open AccessДокумент6 страницSurviving Sepsis: Going Beyond The Guidelines: Review Open AccessTasya Arsy LiyanaОценок пока нет

- Management of Severe Sepsis: Role of "Bundles": G.C. Khilnani and Vijay HaddaДокумент10 страницManagement of Severe Sepsis: Role of "Bundles": G.C. Khilnani and Vijay HaddaaangrohmananiaОценок пока нет

- 2020 SSC Guidelines For Septic Shock in Children PDFДокумент58 страниц2020 SSC Guidelines For Septic Shock in Children PDFAtmaSearch Atma JayaОценок пока нет

- Early Care of Adults With Suspected Sepsis in The Emergency Department and Out-of-Hospital Environment: A Consensus-Based Task Force ReportДокумент19 страницEarly Care of Adults With Suspected Sepsis in The Emergency Department and Out-of-Hospital Environment: A Consensus-Based Task Force ReportAndrei PopescuОценок пока нет

- Sepsis ArticuloДокумент7 страницSepsis ArticuloJose Adriel Chinchay FrancoОценок пока нет

- Noninvasive Monitoring 2016Документ6 страницNoninvasive Monitoring 2016Maria LaiaОценок пока нет

- Guideline Watch 2021Документ24 страницыGuideline Watch 2021Pedro NicolatoОценок пока нет

- Protokol Sleading ScaleДокумент9 страницProtokol Sleading Scaleb3djo_76Оценок пока нет

- Cherukuri Et Al. 2018 - Home Haemodialysis Treatment and Outcomes, Retrospective Analysis of KIHDNEyДокумент10 страницCherukuri Et Al. 2018 - Home Haemodialysis Treatment and Outcomes, Retrospective Analysis of KIHDNEyShareDialysisОценок пока нет

- 2018 Sepsis Rapid Response TeamsДокумент6 страниц2018 Sepsis Rapid Response TeamsgiseladlrОценок пока нет

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines For The Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis Associated Organ Dysfunction in ChildrenДокумент58 страницSurviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines For The Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis Associated Organ Dysfunction in ChildrenmarianaglteОценок пока нет

- Blake Et Al 2011 Clinical Practice Guidelines and Recommendations On Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy 2011Документ22 страницыBlake Et Al 2011 Clinical Practice Guidelines and Recommendations On Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy 2011Gema CanalesОценок пока нет

- Ferrer 2008Документ10 страницFerrer 2008yusОценок пока нет

- Executive Summary: Supplement ArticleДокумент65 страницExecutive Summary: Supplement ArticleLeo F ForeroОценок пока нет

- Adequcy of HDДокумент22 страницыAdequcy of HDzulfiqarОценок пока нет

- Running Head: Critical Care Nursing: Patients With Severe Sepsis 1Документ7 страницRunning Head: Critical Care Nursing: Patients With Severe Sepsis 1api-487423840Оценок пока нет

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 2021 Highlights For The Practicing ClinicianДокумент8 страницSurviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 2021 Highlights For The Practicing ClinicianMariah BrownОценок пока нет

- Clinical and Experimental Emergency MedicineДокумент56 страницClinical and Experimental Emergency MedicineAlfonso Ga MaОценок пока нет

- Polypill, Indications and Use 2.1Документ12 страницPolypill, Indications and Use 2.1jordiОценок пока нет

- Sobreviviendo A La Sepsis 2016 PDFДокумент74 страницыSobreviviendo A La Sepsis 2016 PDFEsteban Parra Valencia100% (1)

- Terapia Dirigida Por Metas en Cirugía Cardíaca Lobdell2020Документ10 страницTerapia Dirigida Por Metas en Cirugía Cardíaca Lobdell2020Juan Guillermo BuitragoОценок пока нет

- Paper - Guidelines - Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2021Документ67 страницPaper - Guidelines - Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2021Harold JeffersonОценок пока нет

- NEJM JW TopGuidelineWatches 2013Документ30 страницNEJM JW TopGuidelineWatches 2013Hoàng TháiОценок пока нет

- Research ArticleДокумент11 страницResearch ArticleWahyuniОценок пока нет

- Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: Management and Performance ImprovementДокумент10 страницSevere Sepsis and Septic Shock: Management and Performance ImprovementMercedes Del MilagroОценок пока нет

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology: PrefaceДокумент3 страницыBest Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology: PrefaceCarlos AldanaОценок пока нет

- Guía Manejo Del Shock 2023Документ67 страницGuía Manejo Del Shock 2023Alvaro ArriagadaОценок пока нет

- Evidence-Based Medical Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Rapid ReviewДокумент14 страницEvidence-Based Medical Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Rapid ReviewLeo OoОценок пока нет

- Public Policy Series: Allen R. NissensonДокумент5 страницPublic Policy Series: Allen R. NissensonRiki RijaludinОценок пока нет

- Evaluation and Management of Suspected Sepsis and Septic Shock in AdultsДокумент62 страницыEvaluation and Management of Suspected Sepsis and Septic Shock in AdultsGiussepe Chirinos CalderonОценок пока нет

- Septic Shock ChallengesДокумент41 страницаSeptic Shock ChallengesSrinivas PingaliОценок пока нет

- Early TIPS Versus Endoscopic Therapy For Secondary Prophylaxis After Management of Acute Esophageal Variceal Bleeding in Cirrhotic Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsДокумент26 страницEarly TIPS Versus Endoscopic Therapy For Secondary Prophylaxis After Management of Acute Esophageal Variceal Bleeding in Cirrhotic Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trialsray liОценок пока нет

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines For Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021Документ67 страницSurviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines For Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021Khanh Ha NguyenОценок пока нет

- The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Bundle: 2018 UpdateДокумент8 страницThe Surviving Sepsis Campaign Bundle: 2018 Updatefarah anaОценок пока нет

- Rhodes 2015Документ9 страницRhodes 2015Achmad Ageng SeloОценок пока нет

- Early Care of Adults With Suspected Sepsis in The Emergency Department and Out-of-Hospital Environment: A Consensus-Based Task Force ReportДокумент19 страницEarly Care of Adults With Suspected Sepsis in The Emergency Department and Out-of-Hospital Environment: A Consensus-Based Task Force ReportHendra DarmawanОценок пока нет

- 2019 Article 1596Документ9 страниц2019 Article 1596Arina FitrianiОценок пока нет

- Discharge Planning For Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients in A Tertiary Hospital: A Best Practice Implementation ProjectДокумент17 страницDischarge Planning For Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients in A Tertiary Hospital: A Best Practice Implementation ProjectMukhlis HasОценок пока нет

- Updated National and International Hypertension Guidelines: A Review of Current RecommendationsДокумент20 страницUpdated National and International Hypertension Guidelines: A Review of Current Recommendationsapi-320636519Оценок пока нет

- Paed-002 Report - Pharmacological Interventions For Paed PANДокумент36 страницPaed-002 Report - Pharmacological Interventions For Paed PANHosne araОценок пока нет

- Evaluation and Management of Suspected Sepsis and Septic Shock in Adults - UpToDateДокумент37 страницEvaluation and Management of Suspected Sepsis and Septic Shock in Adults - UpToDatebarcanbiancaОценок пока нет

- Management of The Critically Ill Patient With Severe Acute Pancreatitis SCCM ATS 2004Документ13 страницManagement of The Critically Ill Patient With Severe Acute Pancreatitis SCCM ATS 2004Alexis May UcОценок пока нет

- Sepsis - Eval and MGMTДокумент62 страницыSepsis - Eval and MGMTDr Ankit SharmaОценок пока нет

- World Sepsis Day 2021 Webinar SlidesДокумент74 страницыWorld Sepsis Day 2021 Webinar Slidessyukri alhamdaОценок пока нет

- Septic Shock Nursing Research Final ProjectДокумент8 страницSeptic Shock Nursing Research Final Projectapi-313061106Оценок пока нет

- Criterios Diagnóstico para Colangitis-TokioДокумент4 страницыCriterios Diagnóstico para Colangitis-TokioEduardo Martinez AvilaОценок пока нет

- Play Therapy FinalДокумент8 страницPlay Therapy FinalChandru KowsalyaОценок пока нет

- 1.3.1 The Autopsy-1Документ4 страницы1.3.1 The Autopsy-1Alyssa robertsОценок пока нет

- Vibrionics Card Rates: Cards by Jaco Malan Compiled by Tim PittsДокумент45 страницVibrionics Card Rates: Cards by Jaco Malan Compiled by Tim PittsKathi Boem100% (3)

- QR CPG TobacoDisorderДокумент8 страницQR CPG TobacoDisorderiman14Оценок пока нет

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The History, Current View and New PerspectivesДокумент14 страницDiffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: The History, Current View and New PerspectivesPepe PintoОценок пока нет

- Medicine Supplies & First Aid Treatment LogsheetДокумент4 страницыMedicine Supplies & First Aid Treatment LogsheetMark BuendiaОценок пока нет

- Estimated Supplies Needed For 6 MonthsДокумент2 страницыEstimated Supplies Needed For 6 MonthsShielo Marie CabañeroОценок пока нет

- Summative Test Science Y5 SECTION AДокумент10 страницSummative Test Science Y5 SECTION AEiLeen TayОценок пока нет

- Kraniotomi DekompresiДокумент17 страницKraniotomi DekompresianamselОценок пока нет

- Abs & Core Workout Calendar - Mar 2020Документ1 страницаAbs & Core Workout Calendar - Mar 2020Claudia anahiОценок пока нет

- Group Activity 1 - BAFF MatrixДокумент1 страницаGroup Activity 1 - BAFF MatrixGreechiane LongoriaОценок пока нет

- 33 Pol BRF Food Models enДокумент36 страниц33 Pol BRF Food Models enthuyetnnОценок пока нет

- Goat MeatДокумент14 страницGoat MeatCAPRINOS BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR, MEXICOОценок пока нет

- Consumer Behaviour Towards Healtth Care ProductsДокумент46 страницConsumer Behaviour Towards Healtth Care ProductsJayesh Makwana50% (2)

- Format OpnameДокумент21 страницаFormat OpnamerestutiyanaОценок пока нет

- Lacl Acc 0523 EformДокумент12 страницLacl Acc 0523 Eformsilaslee0414Оценок пока нет

- Architecture For AutismДокумент16 страницArchitecture For AutismSivaRamanОценок пока нет

- Nursing Skills FairДокумент4 страницыNursing Skills Fairstuffednurse100% (1)

- Activity 2: General Biology 2 (Quarter IV-Week 3)Документ4 страницыActivity 2: General Biology 2 (Quarter IV-Week 3)KatsumiJ AkiОценок пока нет

- FR 2011 02 23Документ275 страницFR 2011 02 23Ngô Mạnh TiếnОценок пока нет

- Operation Management ReportДокумент12 страницOperation Management ReportMuntaha JunaidОценок пока нет

- SD BIOLINE HIV 12 3.0 BrochureДокумент2 страницыSD BIOLINE HIV 12 3.0 BrochureDina Friance ManihurukОценок пока нет

- SAFed Tests PDFДокумент88 страницSAFed Tests PDFDanОценок пока нет

- CFSS Monitoring Tool 2019Документ7 страницCFSS Monitoring Tool 2019JULIE100% (10)

- Biocontrol in Disease SugarcaneДокумент11 страницBiocontrol in Disease SugarcaneAlbar ConejoОценок пока нет

- Fermented Fruit JuiceДокумент4 страницыFermented Fruit JuiceEduardson JustoОценок пока нет

- DM 2020-0187 - Must Know Covid IssuancesДокумент18 страницDM 2020-0187 - Must Know Covid IssuancesFranchise AlienОценок пока нет

- Altius Annual Leave Policy Wef 1st January 2012 Ver 1.1Документ11 страницAltius Annual Leave Policy Wef 1st January 2012 Ver 1.1Mudassar HakimОценок пока нет

- Psych 7A FinalДокумент16 страницPsych 7A FinalMatthew Kim100% (1)

- Antibiotic SolutionДокумент1 страницаAntibiotic SolutionBodhi DharmaОценок пока нет

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)От EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Рейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedОт EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (82)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDОт EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionОт EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (404)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityОт EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (32)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeОт EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesОт EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (1412)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОт EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОценок пока нет

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsОт EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (4)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsОт EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (42)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaОт EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossОт EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (6)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityОт EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (6)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeОт EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (254)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.От EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (110)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceОт EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (51)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsОт EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (39)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlОт EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (60)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingОт EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1138)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessОт EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (328)