Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Effects of Breakfast On Behavior and Academic

Загружено:

sky dela cruzОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Effects of Breakfast On Behavior and Academic

Загружено:

sky dela cruzАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

REVIEW ARTICLE

published: 08 August 2013

HUMAN NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00425

The effects of breakfast on behavior and academic

performance in children and adolescents

Katie Adolphus*, Clare L. Lawton and Louise Dye

Human Appetite Research Unit, Institute of Psychological Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Edited by: Breakfast consumption is associated with positive outcomes for diet quality, micronutrient

Michael Smith, Northumbria intake, weight status and lifestyle factors. Breakfast has been suggested to positively

University, UK

affect learning in children in terms of behavior, cognitive, and school performance.

Reviewed by:

However, these assertions are largely based on evidence which demonstrates acute

Margaret Anne Defeyter, Northumbria

University, UK effects of breakfast on cognitive performance. Less research which examines the

Wendy Hazel Oddy, Telethon Institute effects of breakfast on the ecologically valid outcomes of academic performance or

for Child Health Research, Australia in-class behavior is available. The literature was searched for articles published between

*Correspondence: 19502013 indexed in Ovid MEDLINE, Pubmed, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library,

Katie Adolphus, Human Appetite

EMBASE databases, and PsychINFO. Thirty-six articles examining the effects of breakfast

Research Unit, Institute of

Psychological Sciences, University on in-class behavior and academic performance in children and adolescents were

Road, University of Leeds, Leeds, included. The effects of breakfast in different populations were considered, including

LS2 9JT, UK undernourished or well-nourished children and adolescents from differing socio-economic

e-mail: pskad@leeds.ac.uk

status (SES) backgrounds. The habitual and acute effects of breakfast and the effects

of school breakfast programs (SBPs) were considered. The evidence indicated a mainly

positive effect of breakfast on on-task behavior in the classroom. There was suggestive

evidence that habitual breakfast (frequency and quality) and SBPs have a positive

effect on childrens academic performance with clearest effects on mathematic and

arithmetic grades in undernourished children. Increased frequency of habitual breakfast

was consistently positively associated with academic performance. Some evidence

suggested that quality of habitual breakfast, in terms of providing a greater variety

of food groups and adequate energy, was positively related to school performance.

However, these associations can be attributed, in part, to confounders such as SES

and to methodological weaknesses such as the subjective nature of the observations of

behavior in class.

Keywords: breakfast, behavior, academic performance, children, adolescents, learning

INTRODUCTION learning in children in terms of behavior, cognitive, and school

Breakfast is widely acknowledged to be the most important meal performance (Hoyland et al., 2009).

of the day. Children who habitually consume breakfast are more The assumptions about the benefit of breakfast for childrens

likely to have favorable nutrient intakes including higher intake learning are largely based on evidence which demonstrates acute

of dietary fiber, total carbohydrate and lower total fat and choles- effects of breakfast on childrens cognitive performance from lab-

terol (Deshmukh-Taskar et al., 2010). Breakfast also makes a oratory based experimental studies. Although the evidence is

large contribution to daily micronutrient intake (Balvin Frantzen quite mixed, studies generally demonstrate that eating breakfast

et al., 2013). Iron, B vitamins (folate, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, has a positive effect on childrens cognitive performance, partic-

vitamin B6 , and vitamin B12 ) and Vitamin D are approxi- ularly in the domains of memory and attention (Wesnes et al.,

mately 2060% higher in children who regularly eat breakfast 2003, 2012; Widenhorn-Muller et al., 2008; Cooper et al., 2011;

compared with breakfast skippers (Gibson, 2003). Consuming Pivik et al., 2012). Additionally, the positive effects of breakfast are

breakfast can also contribute to maintaining a body mass index more demonstrable in children who are considered undernour-

(BMI) within the normal range. Two systematic reviews report ished, typically defined as one standard deviation below normal

that children and adolescents who habitually consume breakfast height or weight for age using the US National Center for Health

[including ready-to-eat-cereal (RTEC)] have reduced likelihood Statistics (NCHS) reference (Pollitt et al., 1996; Cueto et al.,

of being overweight (Szajewska and Ruszczynski, 2010; de la 1998). More recent evidence compares breakfast meals that dif-

Hunty et al., 2013). Breakfast consumption is also associated fer in Glycaemic Load (GL), Glycaemic Index (GI) or both. This

with other healthy lifestyle factors. Children who do not con- evidence generally suggests that a lower postprandial glycaemic

sume breakfast are more likely to be less physically active and response is beneficial to childrens cognitive performance (Benton

have a lower cardio respiratory fitness level (Sandercock et al., and Jarvis, 2007; Ingwersen et al., 2007; Micha et al., 2011; Cooper

2010). Moreover, there is evidence that breakfast positively affects et al., 2012) however the evidence is equivocal (Brindal et al.,

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience www.frontiersin.org August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 1

Adolphus et al. Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

2012). Moreover, it remains unclear whether this effect is specif- morning. Nevertheless, breakfast is the most frequently skipped

ically due to GI or GL, or both, or to other effects unrelated to meal. Between 2030% of children and adolescents skip breakfast

glycaemic response. in the developed world (Deshmukh-Taskar et al., 2010; Corder

Studies rarely investigate the acute effects of breakfast on et al., 2011).

behavior in the classroom and there remains a lack of research Despite intense public and scientific interest and a widely

in this area. This may be, in part, attributed to the complicated promoted consensus that breakfast improves concentration and

nature of the measures used to assess behavior in class and the alertness, Hoyland et al. (2009) were only able to identify 45

need to develop standardized, validated, and comparable coding studies on the effects of breakfast on objectively measured cog-

systems to measure behavior. Similarly, few studies examine the nitive performance in the period of 19502008 in their system-

effects of breakfast on tangible academic outcomes such as school atic review. They concluded that breakfast consumption is more

grades or standardized achievement tests relative to cognitive out- beneficial than skipping breakfast to cognitive outcomes, effects

comes. Whilst crude measures of academic performance may not which were more apparent in children who are considered under-

provide the most sensitive indicator of the effects of breakfast, nourished. They did not consider ecologically valid outcomes of

direct measures of academic performance are ecologically valid, behavior (in-class or at school) and academic performance. This

have most relevance to pupils, parents, teachers, and educational article complements the Hoyland et al. (2009) review by consider-

policy makers and as a result may produce most impact. ing the evidence on the effect of breakfast on behavior (in-class or

Cognitive, behavioral, and academic outcomes are not indepen- at school) and academic performance in children and considers

dent. Changes in cognitive performance are likely to be reflected by the methodological challenges in isolating the effects of breakfast

changes in behavior. An increase in attention following breakfast, from other factors. Findings will be discussed dependent on out-

compared with no breakfast, may be reflected by an increase in come measure and study design with effects evaluated based on

on-task behavior during lessons. Similarly, changes in cognitive breakfast manipulation where possible. The effects of breakfast

performance may also impact school performance and academic in different populations will be considered, including children,

outcomes in a cumulative manner. The beneficial effects of eating adolescents who are undernourished or well-nourished and from

breakfast on cognitive performance are expected to be short term differing socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds. The habitual

and specific to the morning on which breakfast is eaten and to and acute effects of breakfast will be considered along with the

selective cognitive functions. These immediate or acute effects effects of school breakfast programs (SBPs).

might translate to benefits in academic performance with habitual

or regular breakfast consumption, but this has not been evaluated METHODS

in most studies. Short term changes in cognitive function during The literature was searched for original articles and reviews

lessons (e.g., memory and attention) may therefore translate, with published between 19502013 on databases: Ovid MEDLINE,

habitual breakfast consumption, to meaningful changes in school Pubmed, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE

performance by an increased ability to attend to and remember databases and PsychINFO. The search was conducted using the

information during lessons. In class behavior also has important key words breakfast or school breakfast combined with chil-

implications for school performance. This is because a prerequi- dren or adolescents combined with behavio$, on-task,

site for academic learning is the ability to stay on task and sustain off-task, concentration, attention, school performance,

attention in class. Greater attention in class and engagement in academic performance, scholastic performance, academic

learning activities (referred to as on-task behavior) are likely achievement, school grades, school achievement, and edu-

to be associated with a more productive learning environment cational achievement using the Boolean operator and. The $

which may impact academic outcomes in the long term. symbol was used for truncation to ensure the search included

Children may be particularly vulnerable to the nutritional all keywords associated with behavior (behavior, behaviour,

effects of breakfast on brain activity and associated cognitive, behavioural, behavioral). Studies are limited to these out-

behavioral, and academic outcomes. Children have a higher brain comes in children and adolescents (<18 years). The reference

glucose metabolism compared with adults. Positron Emission lists of existing reviews and identified articles were examined

Tomography studies indicate that cerebral metabolic rate of glu- individually to supplement the electronic search. The presenta-

cose utilization is approximately twice as high in children aged tion of the results are organized by two main outcomes: In-class

410 years compared with adults. This higher rate of glucose uti- behavior/behavior at school and academic performance with cor-

lization gradually declines from age 10 and usually reaches adult responding summary tables which detail design, sample, break-

levels by the age of 1618 years (Chugani, 1998). Average cere- fast intervention/dietary assessment, assessment of outcomes and

bral blood flow and cerebral oxygen utilization is 1.8 and 1.3 reported results for each article. A total of 36 studies are included.

times higher in children aged 311 years compared with adults, Fourteen studies included behavior measures, seventeen stud-

respectively (Kennedy and Sokoloff, 1957; Chiron et al., 1992). ies included academic performance measures, and five studies

Moreover, the longer overnight fasting period, due to higher examined both behavior and academic performance.

sleep demands during childhood and adolescence compared with

adults, can deplete glycogen stores overnight (Thorleifsdottir RESULTS

et al., 2002). To maintain this higher metabolic rate, a continuous IN-CLASS BEHAVIOR AND BEHAVIOR AT SCHOOL

supply of energy derived from glucose is needed, hence breakfast Nineteen studies employed behavioral measures to examine the

consumption may be vital in providing adequate energy for the effects of breakfast on behavior at school, either by use of

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience www.frontiersin.org August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 2

Adolphus et al. Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

classroom observations or rating scales usually completed by advantage of breakfast on on-task behavior (Chang et al., 1996;

teachers (Table 1). Four studies included both classroom obser- Benton and Jarvis, 2007; Benton et al., 2007).

vations and rating scales (Kaplan et al., 1986; Milich and Pelham, Benton et al. (2007) observed classroom behavior and reaction

1986; Rosen et al., 1988; Richter et al., 1997). to frustration following three isocaloric breakfast meals of high,

medium or low GL in a sample of young children (mean age: 6

Observations of behavior in the classroom years 10 months) from a school in an economically disadvantaged

Direct measures of classroom behavior were utilized in 11 studies. area. Children spent significantly more time on-task following

Although there are inconsistent findings, the evidence indicated a low GL breakfast meal compared with medium and high GL

a mainly positive effect of breakfast on on-task behavior in the breakfast meals. This effect was specific to the first 10 min of the

classroom in children. Seven of the eleven studies demonstrated observation. Children also displayed fewer signs of frustration

a positive effect of breakfast on on-task behavior. This was appar- during a video game observation, but again, effects were short

ent in children who were either well-nourished, undernourished lived and specific to the initial observation period. No signifi-

and/or from low SES or deprived backgrounds. Two studies car- cant effects were found for distracted behavior. Although meals

ried out in undernourished samples (Chang et al., 1996; Richter aimed to be isocaloric, actual intake across conditions was vari-

et al., 1997) and three studies in children from low SES back- able and the macronutrient content differed between conditions.

grounds (Bro et al., 1994, 1996; Benton et al., 2007) demonstrated Consequently, the difference in classroom behavior may be due to

positive effects on on-task behavior following breakfast. One differences in macronutrient content rather than GL. Four studies

study reported a negative effect of a SBP on behavior in under- failed to find a similar advantage for on-task behavior in chil-

nourished children (Cueto and Chinen, 2008) and three studies dren with Attention Deficit Disorder with hyperactivity (ADD-H)

in children with behavioral problems demonstrated no effect of or behavioral problems (Kaplan et al., 1986; Milich and Pelham,

breakfast composition on behavior (Kaplan et al., 1986; Milich 1986; Wender and Solanto, 1991) or in primary school chil-

and Pelham, 1986; Wender and Solanto, 1991). Most studies dren without behavioral problems (Rosen et al., 1988) following

included small samples of the order of 1030 children which, breakfast meals that differed in sugar content.

although limited in terms of power and generalizability to the Mixed results were reported when comparing the effects of

larger population, are more feasible and appropriate given the breakfast vs. no breakfast in undernourished children. Chang

nature of the data and extensive coding methods required. et al. (1996) examined the effects of breakfast on classroom

behavior in 57 undernourished (< 1 SD weight-for-age of

Intervention studies. Four intervention studies demonstrated a the NCHS reference) and 56 adequately nourished children in

positive effect of SBPs on on-task behavior in undernourished Jamaican rural schools. A significant increase in on-task behav-

and low SES children. Richter et al. (1997) reported a signifi- ior was observed following a 520 Kcal breakfast, which was

cant positive change in behavior from pre to post intervention seen only in the well-equipped school. In the three less well-

in undernourished children aged 8 years. Following a 6-week SBP equipped schools, behavior deteriorated following breakfast with

providing approximately 267 Kcal per day at breakfast, children an observed increase in off-task behavior (talking, movement).

in the intervention group displayed significantly less off-task and The well-equipped school had separate classrooms for each class

out of seat behavior and significantly more class participation and each child had their own desk, an environment probably

(Richter et al., 1997). Concomitant teacher ratings of hyperactiv- more conducive to positive in-class behavior. The deterioration

ity also declined significantly in the intervention group, however of behavior following breakfast in the less well-equipped schools

teachers reported no change in attention. This effect has also been could reflect greater difficulties in accurately observing whether

demonstrated in adolescents. Two studies in small samples of ado- children are on-task or off-task when they do not have their own

lescents aged 1419 years showed an increase in on-task behavior desk or are in overcrowded classrooms. In developed high income

in the classroom following an unstandardized teacher led SBP in countries where school infrastructure is more standardized and

vocational schools in USA (Bro et al., 1994, 1996). More recent where classrooms are not overcrowded, this possibly spurious

evidence failed to show the same benefit in undernourished chil- effect is less likely to occur (Murphy et al., 2011; Ni Mhurchu

dren ( 2 SD height-for-age of the NCHS reference) aged et al., 2013). However, negative effects on behavior have also been

11 years. Cueto and Chinen (2008) observed a reduction in on- reported in UK primary and secondary school children within

task behavior following a 3-year SBP measured using time per day deprived areas following a SBP (Shemilt et al., 2004). Therefore,

spent in the classroom as an indirect proxy measure. The design other factors, including the breakfast club environment, delivery,

of the intervention required teachers to dedicate time to providing and staff engagement with the SBP may have also influenced the

the breakfast mid-morning. This unexpected negative impact on impact of breakfast on behavior, as well as school structure. For

on-task behavior is unlikely to occur when breakfast is delivered example, activities during the breakfast club and general atmo-

before school by non-teaching staff and when direct measures of sphere may promote negative and excitable behavior. Nutritional

classroom behavior are employed. status did not influence the results of Chang et als study, however,

the degree of undernourishment was mild. It is possible that pos-

Acute experimental studies. Seven studies employed a within- itive effects may be more demonstrable in children who are more

subjects acute experimental design to examine the effects of severely undernourished. In addition, an appropriate environ-

breakfast on classroom behavior across the morning. The find- ment in terms of classroom structure and equipment is needed

ings were inconsistent, with three of the seven studies showing an to accurately observe the effects of breakfast.

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience www.frontiersin.org August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 3

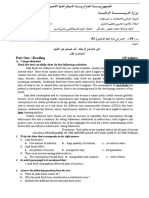

Table 1 | Tabulation of studies investigating the effects of breakfast on behavior at school in children and adolescents.

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Kaplan et al. RM randomized acute Behavior treatment center Behavior problems: In-class observation, +3060 min No significant difference in

(1986) experimental study. (USA). n = 9 aged 913 years. 1. High sugar BF post ingestion. behavior due to high or low

Double blind. Behavior problems: n = 5 2. Low sugar aspartame Behavior coded: on-task during sugar BF.

ADD-H: n = 4. sweetened BF 30 min observation.

ADD-H group: Good inter-rater reliability.

1. High sugar BF + Conners Teacher Rating Scale

Methylphenidate hyperactivity index.

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

2. Low sugar aspartame

sweetened BF +

Methylphenidate

3. High sugar BF + placebo

4. Low sugar aspartame

sweetened BF + placebo

BF of either high or low sugar,

not matched for energy.

Stratified by behavior

problems/ADD-H

Milich and RM randomized acute Behavior treatment center Two conditions: Drink at 0800 h Three observations in two No significant effects of

Pelham (1986) experimental study. (USA). n = 16, male children 1. High sugar: 50 g sugar drink settings. treatment on behavior in both

Double blind. mean age 69 years, 2. Low sugar: 0 g sugar drink + 1. In-class observation via one settings.

diagnosed ADD-H. 175 mg aspartame way mirror. Behavior coded:

on-task, class points, questions

www.frontiersin.org

correct, and questions

attempted for set tasks.

2. Structured recreational

observation (1). Behavior

coded: rule adhering, positive

peer interaction,

noncompliance, negative

verbalization.

3. Structured recreational

observation (2). Behavior

coded: Positive/negative/neutral

interaction.

Good inter-rater reliability.

Conners Teacher Rating Scale

inattention/over-activity and

aggression scales.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 4

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 1 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Rosen et al. RM acute experimental Two schools (USA). n = 45. Three conditions: Standard BF In-class and free play observation No significant effects of sugar

(1988) study. Double blind. Preschool: N = 30, mean and 113 g drink of differing +30 min post BF. on behavior in both settings.

age: 5 years 4 months. sugar content: 1. Preschool: Free play Significant increase in

Male: 66%, Female: 33% 1. High sugar: 50 g sugar drink + observation. Behavior coded: Conners Teacher Rating Scale

Primary school: n = 15, mean BF (489 Kcal/90.8 g CHO) Fidget, activity change, hyperactivity index in high

age: 7 years 2 months. Male: 2. Low sugar: 6.25 g sugar movement, vocalization, sugar condition compared

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

40%, female: 60% drink + BF (314 Kcal/47 g CHO) aggression. with low sugar condition.

Middle-High SES. 3. Control: 0 g sugar drink 2. Primary school. In-class

sweetened with aspartame observation. Behavior coded:

(291 Kcal/41 g CHO) Fidget, on-task.

Standard BF: 198 g oats, 170 g Time sampling. Good inter-rater

whole milk, bread (1 slice), reliability.

1 tsp margarine, 1 tsp grape Conners Teacher Rating Scale

jelly (287 Kcal) 10-item hyperactivity index

Global rating scale completed

by teachers.

Richter et al. SBP evaluation. Pre-post Two primary schools (South Two conditions: Video recorded in-class Significant decrease in

(1997) test design. 6-week Africa). n = 108. 1. SBP: 30 g Cornflakes, 100 ml observation following habituation. off-task and out of seat

intervention. Male: 50%, Female: 50% semi-skimmed milk, banana Behavior coded: on-task, off-task, behavior in SBP group from

Control: n = 55 (267.4 Kcal/1117.8 K) passive-active, positive, or pre- post intervention. No

well-nourished children mean 2. Control: No SBP negative peer interaction, class change in control group.

age SD: 8.3 0.8. participation, out of seat, request Significant increase in activity

www.frontiersin.org

Intervention: n = 53 attention, unclear/out of view. and class participation in SBP

undernourished children Time sampling. group from pre-post

mean age SD: 10.5 1.9. ADD-H Comprehensive Teachers intervention. No change in

Rating Scale 24-item. Teacher control group. Significant

completed four subscales for decline in on-task behavior in

classroom behavior: attention, control group from pre-post

hyperactivity, social skills, and test. No change in SBP

oppositional behavior. group. No significant change

in request attention, negative

peer interaction, and passive

behavior. Hyperactivity

subscale scores declined

significantly in intervention

group from pre-post test.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 5

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 1 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Chang et al. RM randomized acute Four primary schools Two conditions: In-class observation at Significant school

(1996) experimental study. (Jamaica). n = 113, Male: 1. In-class BF before school: 68 g 09001130 h. Two mock treatment interaction for

50%, Female: 50% bread, 28 g cheese, 227 g classroom situations: active teaching on-task, talks,

Undernourished (< 1 SD chocolate milk (520 Kcal) 1. Active teaching (2 30 min) and gross motor behavior and

weight-for-age NCHS): 2. Low energy control: 68 g 2. Set task (2 30 min) for set task on-task behavior.

n = 57, mean age SD: orange (18 Kcal) Behavior coded: On-task, talking Significant increase in on-task

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

9.68 0.42. to peers, gross motor, class behavior and decrease in

Nourished: n = 56, mean participation. gross motor behavior

age SD: 9.18 0.77. Time sampling. Acceptable-good following BF during active

inter-rater reliability. teaching in well-equipped

school. Significant increase in

talking to peers during active

teaching and decrease in

on-task behavior during set

task in poorly equipped

schools following BF. No

significant effects of

nutritional group and

treatment.

Bro et al. (1994) SBP evaluation. Pre-post Vocational secondary school Two conditions: In-class observation conducted by Increase in on-task behavior

test. 20-day intervention. (USA) n = 10 males aged 1. Teacher led in-class SBP teacher. post SBP compared to

1418 years. High rate of Nutritionally balanced Behavior coded: on-task. baseline.

www.frontiersin.org

off-task behavior at baseline. 2. No SBP Time sampling. Good inter-rater

Low SES. reliability.

Bro et al. (1996) SBP evaluation. Pre-post Vocational and learning center Two conditions: In-class observation conducted by Increase in on-task behavior

test. 9-day intervention. (USA): n = 18, aged 1519 1. Teacher led in-class SBP. Fruit teacher in academic and at follow up compared with

years 17 males, 1 female. juice, milk, English muffins, vocational setting. Behavior baseline in both vocational

Low SES. blueberry muffins, bagels, coded: on-task. and academic setting.

cream cheese, eggs, toast, hot Time sampling. Acceptable Decrease in subjective

cakes Inter-rater reliability in both ratings of ability to stay

2. No SBP settings. on-task at follow up. High

Subjective ratings of ability to stay rate of off-task behavior at

on task. baseline.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 6

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 1 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Benton et al. RM randomized acute Primary school children (UK). Three conditions, 4-week SBP. Two observations. Meal time interaction for

(2007) experimental study. n = 19, Mean age: 6 years, Isocaloric BF at 08150845 h of 1. Video recorded in-class time on-task in first 10 min of

10 months. differing GL observation at 10301100 h class observation.

Low SES school. 1. High GL: Cornflakes, (+135 min post BF) during Significantly more time spent

semi-skimmed milk, sugar, independent quiet work. Time on-task after consuming low

waffle, syrup (305 Kcal/39 GL) sampling. Behavior coded: GL BF compared with med

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

2. Medium GL: Scrambled egg, on-task, looking around room, GL BF and high GL BF. No

bread, jam, spread, yoghurt talking to peers, fidgeting, significant effect of BF on

(284 Kcal/14.8 GL) negatively interacting with other behavior. GL of BF

3. Low GL: Ham, cheese, linseed peers, out of seat. negatively predicted

bread, spread (299 Kcal/5.9 GL) 2. Reaction to frustration performance on video game

measured by response to on first test occasion

difficult video game. Behavior (behavior better after low GL

coded: concentrating, fidgeting, BF).

physical signs of frustration,

negative verbal comments.

Cueto and Chinen SBP evaluation. 11 Primary schools (Peru) Two conditions: Behavior coded: Average time/day Reduction in time spent in

(2008) intervention schools, 9 n = 590. 1. Free Mid-morning SBP: BF spent in classroom with teacher classroom indicative of

control schools. Multiple SBP: n = 300, mean age during school break time at as proxy measure for on-task on-task behavior in

and full grade schools. SD: 11.87 1.77. 10001100 h. Milk-like beverage behavior. intervention schools.

3-year intervention. Male: 51.7%, Female: 48.3% and 6 biscuits (600 Kcal/60% Increased time spent in

Control: n = 290 mean age RDA vitamins and minerals recess following SBP.

www.frontiersin.org

SD: 11.87 1.90. 100% RDA for Iron)

Male: 49.7%, Female: 50.3%. 2. Control: No BF/BF at home

6669% 1st grade children

2 SD height-for-age NCHS

reference.

Wender and RM randomized acute Lab based (USA). n = 26. Two conditions. Isocaloric BF and Video recorded playroom No effects of BF on

Solanto (1991) experimental study. Controls: No ADD-H n = 9, drink (226 g) at 0900 h observation at 1000, 1100, 1200, aggression.

Double blind. mean age SD: 6.7 0.7. 1. High sugar: Bread (1 slice), 1300 h (+60, +120, +180 min

ADD-H: n = 17, butter (5 g), and 35 g sugar post BF and +30 min post lunch).

mean age SD: 6.9 0.6. drink (275 Kcals) Behavior coded: Aggression,

2. Low sugar: Bread (2 slices) hitting, kicking throwing.

butter (15 g), and 0 g sugar drink Time sampling. Good periodic

sweetened 175 mg aspartame inter-rater reliability.

or saccharine. (275 Kcals)

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 7

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 1 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Benton and Jarvis RM, randomized acute Primary school children (UK). Mid-morning snack, 1045 h after In-class observation at Size of BF snack interaction

(2007) experimental study. n = 20. Mean age: 9 years 4 self-reported BF: 11151215 h (+30 min post for on-task behavior. Children

months. 1. Muesli bar 25 g (226 Kcal/35 g mid-morning snack). who consumed <150 Kcal BF

Male: 50%, CHO) Behavior coded: on-task, spent significantly more time

Female: 50%. 2. No snack distracted, disruptive, interacting on-task when a snack was

Children classified depending on with teacher, out of chair. eaten. BF snack interaction

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

energy content of BF: Categories collapsed into on-task for off-task behavior. Children

1. <150 Kcal (Mean SE: or off-task behavior. consuming <150 Kcal BF

61.2 18.5 Kcal) Time sampling. spent significantly more time

2. 151230 Kcal (Mean SE: off-task when no snack

209.7 8.3 Kcal) consumed compared with

3. >230 Kcal (Mean SE: 151230 Kcal and >230 Kcal

270.3 64.8 Kcal) BF. Children who consumed

<150 Kcal BF spent

significantly less time off-task

when a snack was eaten.

Wahlstrom and SBP evaluation. Primary schools (USA) Two conditions: Interviews with teachers and Teachers perceived positive

Begalle (1999) 6 intervention schools. n = 2901 children age 614 1. Intervention: Free SBP questionnaires completed by impact of SBP on social

3 control schools 3-year years. Proportion of children Unstandardized. Average daily teachers. behavior and readiness to

intervention. eligible for FSM or reduced participation rate: 68.997.5% Behavior assessed: Readiness to learn compared with pre

priced meals: 20.477.3%. 2. Control: No SBP learn and social behavior. intervention. Teacher

Number of discipline referrals. reported increase attention

www.frontiersin.org

and concentration following

SBP. Decrease in discipline

referrals following SBP.

Overby and Cross-sectional survey Four secondary schools Questionnaire, 1 item to measure Self-reported behavior. 4-item Frequent breakfast

Hoigaard (2012) study. (Norway). n = 475, mean age BF. BF intake classified as: questionnaire to measure consumption significantly

(SD) 14.6 0.56, Male: 1. Often: BF >5 days/week disruptive behavior in class. associated with decreased

49.7%, Female: 50.3%. 2. Never/seldom: BF 5 days/per Score range: 420. Higher scores odds of behavior problems

week indicating poorer behavior. Total (AOR: 0.29 95% CI:

scores dichotomized into two 0.150.55) compared with

categories: never/seldom consumption

No behavioral problems: 411 following adjustment for

Behavioral problems: 1220 gender and BMI.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 8

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 1 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Murphy et al. SBP evaluation. Pre-post Three primary schools (USA) Free SBP. Considered nutritionally Conners Teacher Rating Scale Significantly greater

(1998) test. 4-month intervention. n = 133 mean age SD: balanced including milk, RTEC, hyperactivity index 10-item. decreases in hyperactivity

10.3 1.6 years. bread, muffin, fruit, juice. scores in children who

Male: 44%, Female: 56%. Stratified by SBP participation: increased participation in SBP

Proportion of children eligible 1. Often: 80% attendance post intervention compared

for FSM or reduced priced 2. Sometimes: 2079% with children who had not

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

meals: >70%. attendance changed SBP participation.

3. Rarely: <20% attendance

Ni Mhurchu et al. Cluster RCT, stepped Primary schools (New Two conditions: The Strength and Difficulties No significant effect of SBP

(2013) wedge (sequential roll-out Zealand) n = 424 children 1. Free SBP: School run. Questionnaire completed by on behavior vs. control.

of intervention over 1 year aged 513 years. Non-standardized. School teachers. 25 items related to five Proportion of children eating

period). SBP evaluation. 14 Male: 47%, Female: 53%. selected food: Low sugar dimensions: hyperactivity/ BF everyday did not change.

primary schools. 1 year Low SES schools. RTEC, low-fat milk, bread, inattention, emotional symptoms, Decrease in proportion of

intervention. spreads (honey, jam, and conduct problems, peer children eating BF at home,

margarine), chocolate flavored relationship problems, and increase in proportion of

milk powder, and sugar pro-social behavior. children eating BF at school.

2. Control: No SBP PISA Student Engagement

Questionnaire to measure

self-report belonging and

relationships with other students.

Murphy et al. Clustered RCT with a Primary schools (UK). Two conditions: The Strength and Difficulties No difference in classroom

www.frontiersin.org

(2011) repeated cross-sectional n = 4350 baseline, n = 4472 1. Intervention: SBP, Non- sugar Questionnaire completed by behavior in intervention vs.

design. 56 control schools, follow-up aged 911 years. coated RTEC, milk, bread, fruit. teachers. Classroom behavior control schools.

55 intervention schools. Teacher completed behavior Considered nutritionally rated. Hyperactivity/inattention

SBP evaluation. 1 year assessment on sub-sample balanced scale used as potential

intervention. of 5 pupils in 2 year groups. 2. Control: No SBP, wait listed relationship with on-task behavior.

Control: n = 473 Intervention: control

n = 485.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 9

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 1 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Shemilt et al. Clustered RCT with Primary and secondary Two conditions: The Strength and Difficulties Significantly higher proportion

(2004) observational analysis due schools (UK) n = 6042 1. Funding for free SBP Questionnaire. Teachers of primary school BF club

to contamination between Control: n = 2369, mean 2. Control: No funding for SBP completed questionnaire for attendees had

treatment arms. 3-month age SD: 10.13 3.93. For analysis of behavior, children primary school children. borderline/abnormal conduct

follow up (CT testing Male: 52%, Female: 48%. classified as: Self-report version for secondary and total difficulties scores

outcomes) and 1 year Intervention: n = 3673, mean 1. Non-attendees: Never attended school children. 25-item related to compared to non-attendees

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

follow up (behavioral age SD: 9.59 2.96 Male: 2. Attendees: Attended at least five dimensions: following adjustment for

outcomes). 49%, Female: 51%. once hyperactivity/inattention, confounders. Significantly

emotional symptoms, conduct higher proportion of

problems, peer relationship secondary school BF club

problems, and pro-social behavior. attendees had

Score dichotomized into normal or borderline/abnormal

borderline/abnormal for each pro-social scores compared

dimension. with non-attendees following

adjustment for confounders.

Adjusted for school type,

gender, FSM status.

OSullivan et al. Cross-sectional survey School children (Australia) Three-day food diary. BF intake Child Behavior Checklist Increase in BF quality

(2009) study. The Western n = 836, aged 1315 years, classified based on 5 core food completed by parents (higher associated with decrease in

Australian Pregnancy Male: 50.7% Female: 49.3% groups defined by AGHE: Bread score indicates poor behavior), internalizing behavior score

cohort study. Majority well-nourished, and cereals, vegetables, fruit, 118-item. and a decrease in

5.7% underweight. dairy, and dairy alternatives, meat, Internalizing behavior: Somatic externalizing behavior scores.

www.frontiersin.org

and meat alternatives. complaints, withdrawal, Increase in BF quality

1. No food or drink/water only anxious/depressed associated with decrease in

2. Non nutritious food and drink Externalizing behavior: total child behavior score.

3. Food from 1 AGHE core food Aggression, delinquency Stepwise decrease in total

group Total behavior: Internalizing score with increasing

4. Food from 2 AGHE core food subscale, externalizing subscale, breakfast quality. Adjusted

group social thought, and attention for: PA, sedentary behavior,

5. Food from 3 AGHE core food problems. weight status, family income,

group maternal education, maternal

age of conception, family

structure, family functioning.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 10

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 1 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of behavior Reported results

of BF

Adolphus et al.

Miller et al. (2012) Prospective cohort study. Preschool- primary school Parental questionnaire, 1 item to Internalizing and externalizing No significant association

Part of ECLS-K national children (USA) n = 21400 at assess family BF frequency. BF subscales of the Social Rating between frequency of family

study. Data collection in baseline, n = 9700 at final classified as frequency/week Scale adapted from Social Skills BF and behavior. Fixed

five waves: 1999 follow up, aged 515 years (07) Rating System. effects model results used as

(preschool), 2000 (grade 1), (mean 6.09 years) Externalizing subscale behavior provides most unbiased

2002 (grade 3), 2004 Male: 51%, Female: 49%. coded: arguing, fighting, angry, estimates: account for all

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

(grade 5), 2007 (grade 8). impulsivity, disturbed activities, controls and eliminates

talked during quiet study. between-subject variation.

Internalizing subscale behavior Extensive controls: Gender,

coded: anxious, lonely, sad, low ethnicity, family SES, parental

self-esteem. education, family income,

Teachers rated behavior until parental job prestige, family

grade 5. Children completed structure, area of residence,

scales at grade 8. Acceptable to language, maternal

good reliability on both scales. employment during

preschool, birth weight,

teaching quality, school

quality, region of residence,

parental working hours,

single parent family.

ADD-H, attention deficit disorder-hyperactivity; AGHE, australian guide to health eating; BMI, body mass index; BF, breakfast; CHO, carbohydrate; CT, cognitive testing; ECLS-K, early childhood longitudinal study

kindergarten cohort; FSM, free school meals; GI, glycaemic index; GL, glycaemic load; IG, independent groups; Kcal, kilocalorie; NCHS, national center for health statistics; PA, physical activity; PISA, programme

www.frontiersin.org

for international student assessment; RCT, randomized control trial; RDA, recommended daily allowance; RM, repeated measures; RTEC, ready to eat cereal; SBP, school breakfast program; SD, standard deviation;

SES, socio-economic status.

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 11

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Adolphus et al. Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

One study examined the effects of breakfast size with or inattention, emotional symptoms, conduct and peer relation-

without a mid-morning snack (Benton and Jarvis, 2007). The ship problems, and pro-social behavior in children. However,

results indicated that children who consumed a small breakfast in both trials, SBP attendance was low and variable, limiting

(<150 Kcal) spent significantly more time on-task when a mid- the potential impact on behavior. The barriers to participation

morning snack was also eaten. This effect was not evident in chil- in SBPs include a lack of parental support, a lack of teaching

dren who consumed more energy at breakfast (151230 Kcal and support, social stigma, busy morning schedules, transport issues

>230 Kcal). Correspondingly, children who consumed <150 Kcal preventing children from getting to school early and breakfast

at breakfast spent significantly more time off-task when no snack clubs causing children to arrive late to the first lesson (Reddan

was eaten compared with children who consumed more energy et al., 2002; McDonnell et al., 2004; Greves et al., 2007; Lambert

at breakfast. This suggests a mid-morning snack is only beneficial et al., 2007).Furthermore, the proportion of children eating

for children who have skipped or eaten very little for breakfast and breakfast everyday remained unchanged whilst the proportion

corrects the energy deficiency. of children eating breakfast at home decreased, suggestive of a

shift in consumption from at-home to at-school, rather than a

Rating scales and questionnaires change/increase in consumption. This may account for the lack of

Twelve studies utilized teacher completed rating scales to assess observed effects on behavior. Shemilt et al. (2004) indicated a neg-

childrens behavior at school following breakfast. These studies ative impact of a SBP on behavior in both primary and secondary

usually employed global scales to assess a range of behavioral school children within deprived areas. Although this study aimed

domains including: attention, disruptive behavior, hyperactivity, to employ a RCT design, contamination between treatment arms

pro-social behavior, and aggression. The majority used standard- necessitated a longitudinal observational analysis of behavioral

ized, established measures of behavior comparable across studies. outcomes and SBP attendance, rather than the planned inten-

Measures included the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire tion to treat analysis. Results at 1 year follow up indicated that

(SDQ), Social Skills Rating System (SSRS), Child Behavior children who attended the breakfast club had a higher incidence

Checklist (CBCL) Conners Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS), and of borderline or abnormal conduct, pro-social, and total difficul-

The Attention Deficit DisorderHyperactivity Comprehensive ties compared to children who did not attend the breakfast club

Teachers Rating Scale (ACTeRS). Of the 12 studies that utilized (Shemilt et al., 2004). Teachers also indicated that children were

rating scales and questionnaires, only two studies used unstan- more energetic, less well-behaved and were difficult to control in

dardized questionnaires and interviews with teachers to measure the classroom as a result of attending the breakfast club. Parallel

behavior (Wahlstrom and Begalle, 1999; Overby and Hoigaard, qualitative data from teachers, breakfast club staff and researchers

2012). Six of the twelve studies demonstrated a positive effect of who observed the breakfast club suggested that childrens behav-

breakfast on behavior at school, which was mainly hyperactivity ior deteriorated during the breakfast club as a result of inadequate

and disruptive behavior. supervision and training, and a lack of teaching staff who seemed

to be regarded with more authority by children. Observations

Intervention studies. Six intervention studies reported mixed of the breakfast club indicated behavior was often boisterous or

evidence for the effects of SBPs on behavior at school. Two stud- disruptive and there was a general lively atmosphere. This sug-

ies in low SES and undernourished children aged 810 years gests that factors associated with the delivery of the SBP had more

reported beneficial effects on hyperactivity (Richter et al., 1997; impact on behavioral outcomes than the subtle nutritional effects

Murphy et al., 1998). In a longitudinal analysis of a 4-month of breakfast in this study. In addition, this study epitomizes the

SBP, Murphy et al. (1998) found significantly greater decreases difficulties in isolating the independent effects of breakfast.

in CTRS hyperactivity scores in children who increased partici-

pation in the SBP compared with children whose participation Acute experimental studies. Three acute experimental studies

was unchanged. Similarly, results from a 6-week SBP in under- examined the effects of breakfast meals that differed in sugar

nourished children indicated a significant decline in ACTeRS content on CTRS hyperactivity, inattention/over-activity and

hyperactivity scores following the SBP, but no change in attention, aggression subscales. Both Milich and Pelham (1986) and Kaplan

social skills and oppositional behavior during lessons (Richter et al. (1986) showed no effect of the sugar content of breakfast

et al., 1997). Wahlstrom and Begalle (1999) reported an increase and behavior in children with ADD-H or behavioral problems.

in social behavior and readiness to learn from interviews with However, Rosen et al. (1988) observed a small significant increase

teachers following a 3-year SBP. Their results also indicated a in hyperactivity scores following a breakfast with high sugar

decrease in overall discipline referrals following the SBP. Whilst content compared with low sugar in children without behavior

this evidence indicates an apparent benefit of SBPs on school problems (Rosen et al., 1988).

behavior, methodological shortcomings, including a lack of ran-

domization and the inclusion of an appropriate control group, Cross-sectional studies. Two cross-sectional studies in well-

cannot preclude the effects of confounding factors. nourished adolescent populations reported a significant asso-

Three recent robust randomized control trials (RCT) that ciation between habitual breakfast consumption and behavior.

address the above inadequacies failed to find a similar benefit for Overby and Hoigaard (2012) found that frequency of break-

school behavior measured by the SDQ following a 1 year inter- fast was significantly associated with less self-reported disruptive

vention. Both Ni Mhurchu et al. (2013) and Murphy et al. (2011) behavior during lessons in adolescents (mean age 14.6 years).

reported no significant effects of a 1 year SBP on hyperactivity, Adolescents who habitually consumed breakfast (>5 days/per

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience www.frontiersin.org August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 12

Adolphus et al. Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

week) had significantly reduced likelihood of disruptive behavior only (Rahmani et al., 2011). Although it was not clear if the sam-

[Odds Ratio (OR): 0.29, 95% CI: 0.150.55] compared with those ple included undernourished children, the effect coincided with

who ate breakfast less frequently (5 times per week). A simi- a significant increase in weight of the girls following the inter-

lar association was also evident between breakfast quality based vention in schools which received the intervention compared to

on the number of food groups within the breakfast meal and control schools. Supportive evidence from Kleinman et al. (2002)

CBCL scores (higher score indicates poor behavior) in adolescents found that following a 6-month SBP, children who had improved

(OSullivan et al., 2009). Higher breakfast quality scores were their nutritional status from at risk (energy and/or >2 nutrients

most strongly associated with lower CBLC externalizing behavior <50% RDA) to adequate significantly increased their mathe-

scores (which indicates aggression and delinquency). The results matics grades. Murphy et al. (1998) reported that following a

indicated a stepwise decrease in total scores on the CBCL with 4-month SBP, children who increased participation were signifi-

increasing breakfast quality, indicative of a possible dose-response cantly more likely to increase their mathematics grades compared

relationship. to those who had decreased or maintained participation.

Prospective cohort studies. Although there is some associative Cross-sectional studies. Seven cross-sectional studies demon-

evidence of a relationship between habitual breakfast consump- strated a consistent positive association between habitual break-

tion and behavior in adolescents, the same relationship was not fast and school grades in adolescents.

apparent in a well-controlled prospective cohort study. Miller Frequency of breakfast consumption was associated with

et al. (2012) reported no association between frequency of break- school performance in five studies. Breakfast skipping (eating

fast and negative behavior (e.g., arguing, fighting, angry, and breakfast <5 days/week) was associated with lower average annual

disruptive) in 21,400 school children aged 515 years following school grades in a sample of 605 Dutch adolescents aged 1118

a 10 years follow up and adjustment for extensive confounders. years who were in higher educational streams (Boschloo et al.,

2012). This association was evident in both sexes and indepen-

ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE dent of age. Additionally, breakfast skipping was associated with

Twenty-two studies employed academic performance measures more self-reported attention problems, which partially mediated

to investigate the effects of breakfast on academic outcomes this relationship. A larger cohort of nearly 6500 Korean adoles-

(Table 2). The academic performance outcomes employed by cents of similar age range (1017 years) demonstrated a similar

studies included either school grades or standardized achieve- association across all ages. However, the association was stronger

ment tests. Twenty-one studies demonstrated that habitual break- in younger children (1011 and 1314 years) than older chil-

fast (frequency and quality) and SBPs have a positive effect on dren (1617 years) (Kim et al., 2003). Effects were seen in both

children and adolescents academic performance. genders, except for in 1011 year olds, where the significant asso-

ciation between regular breakfast intake and school performance

Average school grades was only apparent in boys.

Ten studies examined the effects of breakfast on average school This association is also evident in undernourished adolescents

grades. The majority produced a composite score from school (Gajre et al., 2008). Gajre et al. (2008) demonstrated that eat-

reported grades across a range of subjects, usually considered ing breakfast >4 days/week significantly predicted total average

core subjects. Two studies relied on self-reported school grades grades in a sample of children aged 1113 years, a third of whom

(Lien, 2007) or self-reported subjective ratings of school perfor- were undernourished. Analysis of individual subject domains

mance (So, 2013). Seven of the ten studies were in 1218 year olds, indicated that regular breakfast eaters had significantly higher

reflecting the schooling system in which grading is more common grades for science and English, but not mathematics compared

in older pupils. Only three studies were carried out in primary to children who never ate breakfast (Gajre et al., 2008).

school children aged 711 years (Murphy et al., 1998; Kleinman Lien (2007) demonstrated, in a large sample of adolescents

et al., 2002; Rahmani et al., 2011). One study included children aged 1516 years, that those who never ate breakfast were twice

of low SES (Murphy et al., 1998) and two studies included under- as likely to have lower self-reported school grades compared

nourished children (Kleinman et al., 2002; Gajre et al., 2008). All with those who consumed breakfast every day (7 days/week).

10 studies identified demonstrated that habitual breakfast (fre- This finding was consistent in boys and girls. Moreover, the

quency and quality) and SBPs have a positive effect on children odds of having lower self-reported school grades decreased with

and adolescents school performance, with three studies observ- successive quintiles of breakfast eating frequency suggestive of

ing clearest effects on mathematics grades (Murphy et al., 1998; a dose-response relationship. Recent evidence from an inter-

Kleinman et al., 2002; Morales et al., 2008). net based study demonstrated a similar relationship between

habitual breakfast and self-rated academic performance in over

Intervention studies. Three intervention studies demonstrated 75,500 adolescents aged 1218 years (So, 2013). Regular break-

positive effects of SBPs on school grades, particularly mathe- fast eaters (7 days/week) had increased likelihood of rating their

matics grades in both well-nourished, undernourished and low school performance as higher compared with breakfast skippers

SES children aged 710 years. Effects were demonstrable after (0 day/week).

an intervention period of 36 months. A significant increase in Two studies demonstrated a consistent association between

school grades was apparent following an intervention providing breakfast composition derived from energy and food groups pro-

250 ml 2.5% fat milk at breakfast, which was apparent in girls vided and school grades in adolescents aged 1217 years. Morales

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience www.frontiersin.org August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 13

Table 2 | Tabulation of studies investigating the effects of breakfast on academic performance in children and adolescents.

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Lien (2007) Cross-sectional survey School children (Norway) Questionnaire, 1-item to assess Self-reported most recent grade Increased odds of having low

study. n = 7305 aged 1516 years. BF frequency. BF intake classified for: school grades (3) in children

Male: 49.4%, Female: 50.6%. as: 1. Mathematics who seldom/never ate BF

1. Seldom/never 2. Norwegian compared with everyday

2. 12 days/week 3. English consumption in boys and girls

3. 34 days/week 4. Social Science (AOR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.33.1

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

4. 56 days/week Grade scale: 1 (lowest) to 6 and AOR: 2.0 95% CI:

5. Everyday (highest). 1.33.01, respectively).

Total average grade calculated Adjusted for: parental

and dichotomized as: 3 or >3. education, family structure,

immigrant status, smoking,

dieting, soft drink

consumption.

So (2013) Cross-sectional survey School children (Korea) Internet questionnaire, 1-item to Self-reported academic BF eaters (7 days/week) had

study. Korea Youth Risk n = 75643 mean age SD: assess BF frequency. BF performance rating for previous increased likelihood of rating

Behavior Web-based 15.10 1.75. classified as frequency/week 12 months: higher school performance

survey. Male: 51%, Female: 49%. (07) 1. Very high compared with BF skippers

2. High (0 day/week). AOR males: 1.7,

3. Average 95% CI: 1.571.83; AOR

4. Low females: 1.92, 95% CI:

5. Very low 1.762.97. Adjusted for: age,

Dichotomized into two groups: BMI, smoking, alcohol,

www.frontiersin.org

1. <Average academic parental education, family

performance SES, PA (vigorous and

2. Average academic moderate), muscular

performance strength, mental stress.

Murphy et al. SBP evaluation. Pre-post Three primary schools (USA) Free SBP. Considered nutritionally School reported grades for: Higher mathematics grades

(1998) test. 4-month intervention. n = 133 mean age SD balanced including milk, RTEC, 1. Mathematics post intervention in children

10.3 1.6 years. bread, muffin, fruit, juice. 2. Reading who regularly participate in

Male: 44%, Female: 56%. Stratified by SBP participation: 3. Science SBP compared to those who

Proportion of children eligible 1. Often: 80% attendance 4. Social studies rarely or sometimes

for FSM or reduced priced 2. Sometimes: 2079% Letter grade converted into participate. Children who

meals: >70%. attendance numeric value: A = 4, B = 3, increased their SBP

3. Rarely: <20% attendance C = 2, D = 1, F = 0. participation were

significantly more likely to

increase mathematics grades

compared to those who had

decreased or unchanged

participation. No effects of

SBP on other grades.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 14

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 2 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Kleinman et al. SBP evaluation. Pre-post Primary schools (USA) n = 97 Two conditions, SBP. School grades obtained from Significant increase in

(2002) test. 6-month intervention. aged 912 years. 1. Free SBP for 6 months school records: mathematics grades in

Nutritionally at risk (energy 2. No SBP 1. Mathematics children who improved

and/or >2 nutrients <50% 2. Reading nutritionally status from at

RDA): n = 29. 3. Science risk to adequate post

Adequate: n = 68. 4. Social Studies intervention.

Letter grade converted into

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

numeric value: A = 4, B = 3,

C = 2, D = 1, F = 0.

Rahmani et al. SBP outcome evaluation, Four primary schools (Iran) Two conditions: Average grade point. Girls had significantly higher

(2011) IG. 2 intervention schools, n = 469 1. School feeding program: 250 ml average grade point following

2 control schools. 3-month Male: 49% mean age SD: 2.5% fat milk at 0930 h intervention compared with

intervention. 7.9 0.8 years. 2. Control: No milk control. Girls were

Female: 51%, mean age significantly higher in weight

SD: 7.5 0.9 years. Medium following intervention

SES. compared with control.

Gajre et al. (2008) Cross-sectional survey School children (India) Questionnaire to assess BF End of year grades for: Regular BF group had

study. n = 379 aged 1113 years. eating frequency and type. BF 1. Mathematics significantly higher marks for

Male: 55% defined as first eating occasion 2. Sciences science, English and total

Female: 45% during the morning before school. 3. English grade compared to no BF

Underweight: 20.8% BF intake classified as: Total average grade and individual group.

www.frontiersin.org

Stunted: 38.5% 1. Regular: >4 days/week subject grades used in analysis. Regular BF significantly

NCHS reference. 2. Irregular: Skipping BF 23 predicted total average grade.

days/week Regular BF and education of

3. Never mother predicted English

Composition of breakfast not grades. Regular breakfast,

reported type of family and height for

age significantly predicted

science grades. No

association between BF and

mathematics grades.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 15

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 2 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Morales et al. Cross-sectional survey School children (Spain) Seven-day food diary (Mon-Sun) Average end of course grades: Full and good quality BF

(2008) study. n = 467 aged 1217 years. and FFQ. BF intake classified as: 1. Language groups associated with

Male: 42%, Female:58%. 1. Full BF: >25% of TE, includes 2. Mathematics higher total, mathematics,

4 foods groups of dairy, 3. Chemistry chemistry, and social science

cereals, fruit, fat 4. Biology grades compared with no BF.

2. Good quality: 3 food groups of 5. Social Sciences Physical education, biology,

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

dairy, cereals, and fruit 6. Physical education and languages grades were

3. Better options: Missing one Total average grade calculated. highest in no BF group

food group compared with full and food

4. Poor quality: Missing two food quality BF groups.

groups

5. No BF

Boschloo et al. Cross-sectional survey School children (Netherlands) Questionnaire, 1-item to assess Average end of year school BF skipping significantly

(2012) study. n = 605 aged 1118 years. BF frequency on school days. BF grades: associated with lower school

Male: 44%, Female: 56%. classified as: 1. Dutch performance and more

All children in advanced 1. BF eaters: 5 days/week 2. Mathematics self-reported attention

educational tracks in 2. BF skippers: <5 days/week 3. English as a foreign language problems. Attention problems

secondary schools. Grade range: 1(very bad) to 10 partially mediated the

(outstanding) relationship between BF

Attention problems: Attention skipping and school

Problems Scale from the Dutch performance. Adjusted for:

Youth Self Report. age, sex, educational track,

www.frontiersin.org

parental education.

Kim et al. (2003) Cross-sectional survey School children (Korea) FFQ and dietary behavior Average grade from last school Regular BF associated with

study. n = 6463 aged 1011, 1314, questionnaire. BF intake classified semester. Scores range from 15 higher average grade in 1011

1617 years. as: obtained from school records years old boys, higher

Male: 53%, Female: 47%. 1. Regular BF 1. Korean average grade in 1314 years

2. No regular BF 2. Mathematics old boys and girls and higher

3. Social Studies average grade 1617 years

4. Science old boys and girls. Adjusted

5. Physical education for: parental education,

6. Music physical fitness, physical

7. Art status.

8. Practical course

9. Ethics

10. English (grade 8 and 11)

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 16

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 2 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Herrero Lozano Cross-sectional survey School children (Spain) Recall BF of previous day (1 day Average end of year grade. Significantly higher average

and Fillat study. n = 141 aged 1213 years. only). BF intake classified as: grades obtained in good

Ballesteros Male: 49.6%, Female: 50.4%. 1. Good quality: 3 food groups of quality BF groups compared

(2006) dairy, cereals and fruit with poor quality. Average

2. Improvable quality: Missing grade increased when good

one of the food groups quality snack was eaten in

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

3. Insufficient quality: Missing poor and insufficient BF

two food groups quality groups.

4. Poor quality: No BF

Contribution of a mid-morning

snack to BF considered

Cueto and Chinen SBP evaluation. 11 Primary schools (Peru) Two conditions: Unstandardized tests developed Higher arithmetic and reading

(2008) intervention schools, 9 n = 590. 1. Free Mid-morning SBP: BF to account for variability in scores in multiple grade

control schools. Multiple SBP: n = 300, mean age during school break time at curriculum: intervention schools

and full grade schools. SD: 11.87 1.77. 10001100 h. Milk-like beverage 1. Arithmetic compared to control post

3-year intervention. Male: 51.7%, Female: 48.3% and 6 biscuits (600 Kcal/60% 2. Reading comprehension intervention. No significant

Control: n = 290 mean age RDA vitamins and minerals effect of SBP in full grade

SD: 11.87 1.90. 100% RDA for iron) schools.

Male: 49.7%, Female: 50.3% 2. Control: No BF/BF at home

6669% 1st grade children

2 SD height-for-age NCHS.

www.frontiersin.org

Acham et al. Cross-sectional survey School children (Uganda) Questionnaire, 1-item to assess Unstandardized tests: Developed Boys who had consumed BF

(2012) study. n = 645 aged 915 years. BF frequency. to account for variability in school and mid-day meal were

Male: 46%, Female: 54% BF intake classified as: environment. significantly more likely to

Underweight: 13% 1. BF 1. English score 120 than those who

Stunted: 8.7%. 2. BF and/or mid-day meal 2. Mathematics only had one meal (OR: 1.99

3. No BF or mid-day meal 3. Life Skills 95% CI: 1.03.9). No

4. Oral comprehension association between BF

Maximum score of 400. Cut-off of alone and test scores.

<120 used to define poor Adjusted for household size,

performance. mothers education, land

68.4% scored <120. quantity owned, school

attendance, gender head of

household, feeding habits,

age, household wealth.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 17

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 2 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Powell et al. SBP evaluation. RCT. 1 16 Primary schools. (Jamaica) Two conditions: The Wide Range Achievement Significant positive effect of

(1998) school year intervention. n = 810 children aged 711 1. Intervention: Free SBP. Cheese Test: BF on Arithmetic. Grade

years. sandwich/spiced bun and 1. Reading Treatment interaction

Undernourished (< 1 SD cheese, flavored milk 2. Spelling indicated the positive effect

weight-for-age NCHS): 405 (576703 Kcal/27.1 g 3. Arithmetic on arithmetic scores was

Nourished: 405. PRO). Served before school mainly demonstrated in

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

2. Control: orange (18 Kcal/0.4 g younger children. No effects

PRO) of BF on spelling and reading.

No differential effects by

nutritional group.

Simeon (1998) SBP evaluation. 1 school School based (Jamaica) Three condition. BF at 0900 h. 1 The Wide Range Achievement Syrup drink and no BF groups

Study 1 semester intervention. n = 115.1213 years school semester intervention. Test: combined to form one control

Rural schools, low ability 1. School BF: 100 ml milk 1. Spelling group as no significant

children, low attendance at (130 Kcal), cake (250 Kcal), or 2. Arithmetic differences found on all

school meat filled pasty (599 Kcal) 3. Reading (not used in analysis) outcomes. Children receiving

Undernourished: 50%. 2. Syrup drink (31 Kcal) school BF performed better

3. No BF on arithmetic test relative to

control group post

intervention.

Wahlstrom and SBP evaluation. 6 Primary schools (USA) Two conditions: School achievement tests, Within school effects

Begalle (1999) intervention schools, 3 n = 2901 children age 614 1. Intervention: Free SBP Incomparable across schools. (pre-post intervention) show

www.frontiersin.org

control schools. 3-year years. Proportion of children Unstandardized. Average daily 1. Mathematics general increase in scores for

intervention. eligible for FSM or reduced participation rate: 68.997.5% 2. Reading reading and mathematics.

priced meals: 20.477.3% 2. Control: No SBP

Jacoby et al. SBP evaluation. RCT. 10 Primary school (Peru) Two conditions, SBP. Achievement test for: No effects of SBP on any

(1996) 1 month intervention. n = 352. 1. Intervention: SBP: 600 Kcal, 1. Reading comprehension achievement tests.

Intervention: n = 201, mean 60% RDA various vitamins and 2. Vocabulary Significant weight

age SD: 136.2 18 months minerals and 100% RDA iron 3. Mathematics treatment interaction children

Male: 46%, Female: 54% 2. Control: No SBP in intervention schools of

Control: n = 151, mean age higher weight increase

SD: 138.9 20 months. vocabulary scores.

Male:53%, Female 47%

Normal weight and

underweight and stunted

children.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 18

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 2 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Meyers et al. SBP evaluation. pre-post 16 Primary schools (USA) SBP. Stratified by SBP The Comprehension Test of Basic Lower total scores at

(1989) test. 3-month intervention. n = 1023 children aged 812 participation Skills. baseline in non-attendees.

(grades 36) 1. Non attendees: <60% 1. Language Greater increase in total and

Male: 51%, Female: 49% attendance 2. Reading language scores in attendees

Low income. 2. Attendees: 60% attendance 3. Mathematics compared with

non-attendees. SBP

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

attendance positively

associated with total scores

at follow up.

Ni Mhurchu et al. Cluster RCT, stepped Primary schools (New Two conditions: Standardized school achievement No significant effects on

(2013) wedge (sequential roll-out Zealand) n = 424 school 1. Free SBP: Non-standardized. tests: achievement tests, self-report

of intervention over 1 year children aged 513 years. School selected food: Low 1. Literacy reading ability and

period). SBP evaluation. 14 Male: 47%, Female: 53%. sugar RTEC, low-fat milk, 2. Numeracy attendance. Proportion of

primary schools. 1 year Low SES schools. bread, spreads (honey, jam, Self-report assessment of reading children eating BF everyday

intervention. margarine), chocolate flavored ability using questionnaire. Scores did not change. Decrease in

milk powder, and sugar from 1 (not very well) to 5 (very proportion of children eating

2. Control: No SBP well). BF at home, increase in

proportion of children eating

BF at school.

Edwards et al. Cross-sectional survey School children (USA) Adapted questions from Youth MAP tests. Standardized Higher mean mathematics

(2011) study. n = 800 aged 1113 years. Risk Behavior Surveillance survey. computer tests for MAP scores associated with

www.frontiersin.org

n = 694 complete data on BF intake classified as 1. Mathematics eating BF 5 days/week

gender 1. BF 5 days/week 2. Reading compared with <5

Male: 48%, Female: 52% 2. BF < 5 days/week days/week. Regression

13.5% eligible for FSM. analysis indicated BF intake

was significantly associated

with mean MAP

mathematics scores. No

association between BF and

MAP reading scores:

Adjusted for: FSM status.

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 19

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 2 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Lopez-Sobaler Cross-sectional survey School children (Spain) Weighed 7-day food diary. Spanish SAT-1 test. Three Higher reasoning SAT-1

et al. (2003) study. n = 180 aged 913 years. Definition of BF: Cut-off of 20% sub-batteries: scores obtained by AB group

Male: 57%, Female: 43%. of daily energy requirement. BF 1. Verbal compared with IB group.

intake classified as: 2. Reasoning Higher total SAT-1 scores

1. AB: 20% of daily energy 3. Calculation obtained by AB group

requirement Direct scores, centile scores, and compared with IB group.

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

2. IB: <20% of daily energy IQ score obtained. Better quality breakfast

requirement significantly predicated better

reasoning and total scores.

ODea and Cross-sectional survey School Children (Australia) Questionnaire and interview with Standardized school achievement Nutritional quality of BF

Mugridge (2012) study. n = 824 grades 37 (aged dietitian. BF defined as solid or tests, NAPLAN test scores for: significantly predicted literacy

813 years). liquid eaten before 1000 h on day 1. Literacy scores. Non-significant

Male: 49%, Female: 51% of testing. BF intake classified as: 2. Numeracy association between BF and

n = 755 parents. 0. No food/drink numeracy scores. Few

1. Non-nutrient liquid children skipped BF. Adjusted

2. Confectionary/snack food for: age, gender, SES,

3. Grain/cereal or fruit/vegetable maternal education.

4. Grain/cereal + vitamin C

5. Protein + vitamin C

6. Grain/cereal + protein or

Grain/cereal + calcium

7. Grain/cereal + protein +

www.frontiersin.org

vitamin C or Protein +

calcium + vitamin C

8. Grain/cereal + protein +

calcium

9. Grain/cereal + protein +

calcium + vitamin C

10. Grain/cereal + protein +

Vitamin C + calcium including

low-fat option

(Continued)

August 2013 | Volume 7 | Article 425 | 20

Breakfast, behavior, and academic performance

Table 2 | Continued

Authors, year Design Sample BF intervention/assessment Assessment of school Reported results

of BF performance

Adolphus et al.

Miller et al. (2012) Prospective cohort study. Preschool-primary school Parental questionnaire, 1 item to Standardized achievement tests No significant association

Part of ECLS-K national children (USA) n = 21400 at assess family BF frequency. BF 1. Reading between frequency of family

study. Data collection in baseline, n = 9700 at final classified as frequency/week 2. Mathematics BF and test scores. Fixed

five waves: 1999 follow up, aged 515 years (07) 3. Science (grades 3, 5, 6) effects model results used as

(preschool), 2000 (grade 1), (mean 6.09 years) provides most unbiased

2002 (grade 3), 2004 Male: 51%, Female: 49%. estimates: accounts for all

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience

(grade 5), 2007 (grade 8). controls and eliminates

between subject variations.

Extensive controls. Adjusted

for: Gender, ethnicity, family

SES, parental education,

family income, parental job

prestige, family structure,