Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Notes The Law of Treaties

Загружено:

evelinanicolaeОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Notes The Law of Treaties

Загружено:

evelinanicolaeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SECTION 3 THE LAW OF TREATIES

Introduction

Legal rights and duties in municipal law may be created by contracts between

parties, agreements under seal, legislation or judicial decisions.

Customs and treaties usually create legal rights and duties in international

law.

Custom relies upon a measure of state practice supported by opinio juris.1

By contrast, treaties are a more direct and formal method of international law

creation.2

Treaties between states are primarily governed by the Vienna Convention on

the Law of Treaties 19693 whilst those between States and international

organisations are governed by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties

between States and International Organisations 1986.

What is a Treaty?

Article 2 of the1969 Vienna Convention defines a treaty as:

An international agreement concluded between states in written

form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a

single instrument or in two or more related instruments and

whatever its particular designation.

An agreement between parties in the international arena.

The fundamental principle of treaty law is that treaties are binding upon

parties to them and must be performed in good faith.

The term pacta sunt servanda expresses this principle which is arguably the

oldest principle of international law. See Art. 26.

Formalities

No specific requirement of form in international law for the existence of a

treaty.

Parties must however intend to create legal relations as between themselves

by means of their agreement.

Where the parties to an agreement do not intend to create legal relations the

agreement will not be a treaty, but its political effect may still be considerable.

E.g. memoranda of understanding. Such agreements may have the benefit of

flexibility and could be amended as required.

Each state decides where the power to create treaties is derived from in their

municipal law and it differs from state to state. E.g. in the United Kingdom the

treaty-making power is within the prerogative of the Crown, whereas in the

United States it resides with the president with the advice and consent of the

Senate and the concurrence of two-thirds of the Senators.4

1 An opinion of law. It is the belief that an action was carried out because it was a

legal obligation.

2 Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (6th edn, Cambridge University Press 2008)

902

3 It however also applies to agreements between states within an international

organisation. See Art. 3(c) VCLT.

4 E.g. Cameroon v Nigeria, 2002 ICJ Reports 303, 429

Full powers must be produced by representatives of the states. 5

Certain persons need not produce such full powers by virtue of their position

and functions. E.g. Heads of state and government. Foreign ministers, heads

of diplomatic missions and representatives accredited to international

conferences or organisations may not need to produce full powers for specific

purposes. See Genocide Convention (Bosnia v Serbia) case where the

International Court noted in the preliminary objections to jurisdiction, that

according to international law, there is no doubt that every head of state is

presumed to be able to act on behalf of the state in its international relations.6

Any act relating to the making of a treaty by a person not authorised as

required will be without any legal effect, unless the state involved afterwards

confirms the act.

Consent

The text of the agreement has to be adopted for a treaty to become binding.

Adoption in international conferences take place by the vote of two-thirds of

the states present and voting, unless by the same majority it is decided to

apply a different rule. In cases other than international conferences, adoption

will take place by the consent of all the states involved in the drawing up of

the text of the agreement Art. 9.

Methods of Expressing Consent

Article 11 sets out different ways in which states may express their consent:

Consent by signature.7

Consent by exchange of instruments.8

Consent by ratification9

Consent by acceptance

Consent by approval or accession.10

It may also be accomplished by any other means if so agreed.

Reservations to Treaties

A reservation is defined in Art. 2 (1) (d) of the Convention as:

A unilateral statement, however phrased or named, made by a

state, when signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding

to a treaty, whereby it purports to exclude or to modify the legal

effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to

that state.

It is a device utilised by states where they agree to certain provisions of a

treaty but disagree with certain others. By putting in a reservation to those

provisions they disagree with, they will not be bound by them.

5 See Article 7 Vienna Convention

6 [1996] ICJ Rep 595,622

7 Article 12 Vienna Convention

8 Article 13 Vienna Convention

9 Article 14 Vienna Convention

10 Article 15 Vienna Convention

Reservations are beneficial to the development of international law as they

enable states to agree to be bound (at least in part) by a treaty they would

otherwise have totally rejected.

Whilst reservation enhances the principle of sovereignty of states, it cannot

be over utilised as this would lead to a treaty that is very much altered from

what it was intended to be. The effectiveness of the treaty would be

compromised if there were untold reservations to several of its provisions.

This is a problem that does not arise in bilateral treaties as objection by one

party would necessitate a renegotiation.

Reservations can be distinguished from understandings, political statements

or interpretative declarations, where no binding consequence is intended with

regard to the treaty in question. See Anglo-French Continental Shelf case

Cmnd 7438 (1979); 54 ILR 6, Belilos case European Court of Human Rights,

Series A No 132.11

The general rule was that reservations could only be made with the consent

of all the other states involved in the process. Where such consent was not

obtained, the state could either become a party to the original treaty or note

become a party at all. Contrast with the view of the International Court of

Justice in the Reservations to the Genocide Convention case.12 The Courts

views are reflected in Art 19.

However, where the application of the treaty in its entirety between all the

parties is an essential condition of the consent of each one to be bound by

the treaty, then the traditional rule of acceptance by all parties will still apply to

a reservation. Art 20(2).

A reservation has the effect of modifying the provisions of the treaty to which

it relates to the extent of the reservation between the states Art 21.

There are differing views in relation to impermissible reservations. One view

is that such reservations are invalid while the other is that the validity of any

reservation is dependent on acceptance by other states.

In general, reservations are deemed to have been accepted by states that

have raised no objection to them at the end of a period of twelve months after

notification of the reservation, or by the date on which consent to be bound by

the treaty was expressed, whichever is the later. See Art 20(5).

Reservations must be in writing and communicated to the contracting states

and other states entitled to become parties to the treaty. Acceptances and

objections to the reservations must also be in writing. See Art 22(3) for

withdrawal of reservations.

Entry into Force and Application of Treaties

In the absence of any provision or agreement regarding this, a treaty will

enter into force as soon as consent to be bound by the treaty has been

established for all negotiating states Art 24.

Where ratification is required, only those states that ratify the treaty would be

bound except in instances where signature is deemed sufficient to express

the consent of the state to be bound.

A treaty will not operate retroactively except a contrary intention is expressed

Art 28.

11 See also S Marks, Reservations Unhinged: the Belios Case Before the European

Court of Human Rights 39 (1990) ICLQ 300

12 [1951] ICJ Rep 15; 18 ILR 364

It would also apply to all the territory of the state except a contrary intention is

expressed Art 29. E.g. colonial application clauses.

Where there are successive treaties on the same subject matter, Art 30

provides a general guide on how to deal with such issues but in most cases

the parties resolve thus with express terms.

Application of Treaties to Third States

Third states are states that are not parties to the treaty in question.

The general rule is that international agreements bind only the parties to

them. The rationale for this can be found in the principle of the sovereignty

and independence of states. See Art 34.

However, where the provisions of a particular treaty have entered into

customary law, all states would be bound, regardless of whether they had

been parties to the original treaty or not.

Parties may also include a term in a treaty that creates an obligation on a

third state. Such obligation must be expressly accepted by the third state in

writing. Art 35

In relation to rights allocated to third states from a treaty, it must be

ascertained whether the states which have stipulated in favour of a third state

meant to create for that state an actual right which the latter has accepted as

such.13 A states assent shall be presumed so long as the contrary is not

indicated, unless the treaty otherwise provides - Art 36.

Where a treaty creates obligations or rights erga omnes14, all States would be

bound by them and also benefit from them. In the Wimbledon case, the

Permanent Court noted that an international waterway...for the benefit of all

nations of the world had been established.

The Amendment and Modification of Treaties

Amendments are the formal alteration of treaty provisions. Affects all the

parties to the particular agreement.15

Amendments to treaties have to follow the usual formalities laid down for the

coming into effect of a treaty unless the treaty otherwise provides Art 39.

Many multilateral treaties lay down specific conditions as regards

amendment. E.g. the UN Charter provides for the conditions for amendment

in Art 108.

Article 40 of the Convention provides the procedure to be adopted where

there are no specific conditions for amendment and some parties oppose the

amendment.

When a party becomes a party to a treaty after an amendment, they will only

be bound by the amended agreement except in regard to parties that are not

parties to the amendment who will then be bound only by the original

agreement.

Modifications relate to variations of certain treaty terms as between particular

parties only. It can be achieved by two or more parties to a multilateral treaty

13 Permanent Court of International Justice in Free Zones case PCIJ Series A/B No

46 1932, 147-8, 6 AD

14 In relation to everyone.

15 Malcolm N Shaw, International Law (6th edn, OUP 2008) 930

provided it has not been prohibited by the treaty in question and provided it

does not affect the rights or obligations of the other parties.

Where a modification is going to interfere with the effective execution of the

object and purpose of the treaty as a whole, it will not be possible Art 41.

A treaty may also be modified by the terms of another later agreement16 or

by a subsequent rule of jus cogens.

Treaty Interpretation

There are three basic approaches to interpretation of treaties in international law:

The subjective (intention) of the parties approach

The objective (textual) approach

The teleological (object and purpose) approach.

These schools of interpretation are not mutually exclusive.

For the International Law Commission the starting point was the text rather

than the intention of the parties, since it presumed that the text represented a

real expression of what the parties did in fact intend. It also appears that the

ICJs preferred method of interpretation is reliance on the text of a treaty.17

Articles 31 to 33 contain to a certain extent, some measure of all three

schools of interpretation.

Invalidity of Treaties

The validity and continuance in force of a treaty can only be questioned on

the basis of the provisions in the Vienna Convention Art 42.

In certain instances a state would be unable to rely on any of the grounds for

invalidity due to its express or implied conduct. See Art 45.

The grounds for invalidity of treaties within the Convention can be divided into

two: relative grounds and absolute grounds. The primary difference between

these grounds is that the relative grounds render a treaty voidable at the

insistence of an affected State whereas the absolute grounds mean that the

treaty is rendered void ab initio and without legal effect.

Relative Grounds of Invalidity:

Municipal law- Art. 46. Failure by a state to comply with its internal law

regarding competence to conclude a treaty many only be a ground for

invalidating consent to be bound if that failure was manifest. See

Cameroon v Nigeria Case.18 See Article 47 for a similar provision where

the representatives purporting to conclude the treaty were acting beyond

the scope of their instructions.

Error Art 48. Although error is an invalidating factor, a state will not be

able to rely on that error if it knew or ought to have known of the error, or if

it contributed to that error. See Temple case.19

Fraud and corruption: fraudulent conduct of a negotiating state can be

relied upon as a ground for invalidity Art 49. Direct or indirect corruption

16 Art. 30

17 MD Evans (ed), International Law (OUP 2010) 199

18 [2002] ICJ Rep 303

19 [1960] ICJ Rep 6

of a representative of another sate by a negotiating state can also be

relied upon as a ground of invalidity- Art 50.

However note that as far as corruption is concerned, the ILC observed

that only an act calculated to exercise a substantial influence on the

disposition of a representative to conclude a treaty could be invoked as a

reason to invalidate an expression of consent that had subsequently been

given.20

Absolute Grounds of Invalidity

Coercion: Where the consent of a state to be bound by a treaty has been

procured by coercion of its representative, the treaty is void. Art 51.

Where a state has been coerced in contravention of the UN Charter, the

treaty will be void- Art 52. See the Fisheries Jurisdiction case.21

Jus cogens: A treaty that conflicts with norms of jus cogens will be void.

Art 53.

See also Art 64.

Effect of Invalidity

An invalid treaty is void and without legal force subject to the provisions of

article 69. For treaties void under Article 53, Article 71 applies and parties

are allowed to being their mutual relations into conformity with the

peremptory norm.

Termination and Suspension of Treaties

A State may only withdraw from or suspend the operation of a treaty in

respect of the treaty as a whole and not particular parts of it, unless the treaty

otherwise stipulates or the parties otherwise agree Art 44.

A treaty may come to an end if its purposes and objects have been achieved.

This does not affect any right, obligation or legal situation of the parties

created through the execution of the treaty prior to its termination.

Grounds for Termination and Suspension

Treaty provision or consent- Arts 54 and 57

Achievement of object and purpose.

A multilateral treaty may be suspended between two or more parties if the

treaty provides this for. Art 58. This is subject to Art 41.

Tacit termination i.e. where all parties to a treaty enter into another treaty

relating to the same subject matter. The former treaty will be regarded as

terminated - Art 59. Compare this to successive treaties in Art 30.

Material breach- Art 60

Supervening impossibility of performance Art 61

Fundamental change of circumstances Art 62. See the Fisheries

Jurisdiction case.22

Consequences of Termination or Suspension of a Treaty

20 [1996] YBILC vol II 244

21 [1973] ICJ Rep 3; 55 ILR 183

22[1973] ICJ Rep 3

Releases the parties from their obligations under the treaty although it does

not affect any rights, obligations created through the execution of the treaty

prior to its termination- Art 70. See also Art 72.

Article 66 provides for the procedure to follow in dispute settlement.

Unresolved disputes which relate to Articles 53 or 64 may be submitted to the

international Court of Justice by either of the parties for a decision unless the

parties agree to submit the dispute to arbitration.

Treaties Between States and International Organisations

The provisions of the Vienna Convention on the law of treaties between

States and International Organisations 1986 closely follow the provisions of

the 1969 Vienna Convention. Article 73 of the 1986 Convention however

affirms the superiority of the 1969 Convention for states that are parties to the

1969 Convention in relations between two or more states and one or more

international organisation.

The provisions for dispute settlement in Articles 66(2) of the 1986 Convention

differ from those of the 1969 Vienna Convention.

Further Reading

MD Evans (ed), International Law (2nd edn OUP, Oxford 2006) 188-213

MN Shaw, International Law (5th edn Cambridge University Press, Cambridge) 902-

955

A Aust, Modern Treaty law and Practice (2nd edn, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge 2007)

Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law (7th edn, OUP 2008)

Francesco Parisi and Catherine evenko, Treaty Reservations and the Economics

of Article 21(1) of the Vienna Convention (2003) 21(1) Berkeley J Intl Law 1

Questions for Self Assessment

1. How are rights and obligations created in public international law? Which

would you consider to be most effective and why?

2. How can consent to a treaty be expressed?

3. What is a reservation to a treaty and what impact if any does it have in both a

bilateral and a multi lateral treaty?

4. What are the grounds for invalidity of a treaty?

5. How can a treaty be terminated or suspended? What impact does this have?

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Performance Appraisal in An NHS HospitalДокумент15 страницPerformance Appraisal in An NHS HospitalAsan Bazilov0% (1)

- Nicaragua v. Us Case DigestДокумент4 страницыNicaragua v. Us Case DigestAn Jo100% (3)

- Pros Sagssago Notes in Criminal Law 2017 EditionДокумент319 страницPros Sagssago Notes in Criminal Law 2017 EditionAj Ayochok Tactay100% (2)

- Integrated Marketing Communications TemplateДокумент10 страницIntegrated Marketing Communications TemplateevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- Shengen Visa DetailsДокумент17 страницShengen Visa DetailshugocorzoОценок пока нет

- Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964)Документ22 страницыBanco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964)Jumen Gamaru TamayoОценок пока нет

- International Court of JusticeДокумент16 страницInternational Court of JusticeSamiksha GondkarОценок пока нет

- Gayo vs. VercelesДокумент2 страницыGayo vs. VercelesJessamine OrioqueОценок пока нет

- Wal-Mart Strategic ManagementДокумент28 страницWal-Mart Strategic Managementsiang_lui100% (2)

- Integrated Marketing Communications Template PDFДокумент10 страницIntegrated Marketing Communications Template PDFevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- Critical EvaluationДокумент2 страницыCritical EvaluationevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- LeadershipДокумент10 страницLeadershipevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- JTR 3Документ14 страницJTR 3Vetri VelОценок пока нет

- NotesДокумент366 страницNotesevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- Powerpoint Share Capital LLMДокумент15 страницPowerpoint Share Capital LLMevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- 15AsperRevIntlBusTradeL26 PDFДокумент29 страниц15AsperRevIntlBusTradeL26 PDFevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- Mooting Guide - 2012Документ5 страницMooting Guide - 2012Chevanev Andrei CharlesОценок пока нет

- ContentServer - Asp 7Документ9 страницContentServer - Asp 7evelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- Mooting Guide - 2012Документ5 страницMooting Guide - 2012Chevanev Andrei CharlesОценок пока нет

- Appraisal Handbook - NHS 16-17Документ21 страницаAppraisal Handbook - NHS 16-17evelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- Reward-Risks 2012 PDFДокумент20 страницReward-Risks 2012 PDFevelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- Journal of Management 2016 Nyberg 1753 83Документ31 страницаJournal of Management 2016 Nyberg 1753 83evelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- 15 Asper Rev Intl Bus Trade L26Документ29 страниц15 Asper Rev Intl Bus Trade L26evelinanicolaeОценок пока нет

- 312 Nyac I in One DocumentДокумент492 страницы312 Nyac I in One DocumentIrina CraciunОценок пока нет

- BGDCV2B3E023IS020405Документ2 страницыBGDCV2B3E023IS020405JOYNAL ABDINОценок пока нет

- 3.united NationsДокумент5 страниц3.united NationsPopular Youtube VideosОценок пока нет

- Turkey 11122019 (HC) MoU Libya-Delimitation-areas-MediterraneanДокумент15 страницTurkey 11122019 (HC) MoU Libya-Delimitation-areas-MediterraneanGiannis GiannatosОценок пока нет

- Autonomy As A Method of Conflict Management and Protection of Minorities Within The OSCE FrameworkДокумент9 страницAutonomy As A Method of Conflict Management and Protection of Minorities Within The OSCE FrameworkRafael DobrzenieckiОценок пока нет

- Form Visa Indonesia PDFДокумент2 страницыForm Visa Indonesia PDFklaritasabillОценок пока нет

- General Information About Nigerian VisaДокумент67 страницGeneral Information About Nigerian VisasaravananОценок пока нет

- Singapore Chennai Visa ChecklistДокумент2 страницыSingapore Chennai Visa ChecklistSrinivasrao BoraОценок пока нет

- Philippine Embassy Bank Account Case NotesДокумент2 страницыPhilippine Embassy Bank Account Case NotesEva TrinidadОценок пока нет

- The National Laws of Myanmar: Making of Statelessness For The RohingyaДокумент15 страницThe National Laws of Myanmar: Making of Statelessness For The RohingyaArafat jamilОценок пока нет

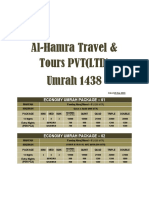

- Counter Umrah PackageДокумент7 страницCounter Umrah PackageAlhamra TravelsОценок пока нет

- Vijay Naidu PeddisettyДокумент1 страницаVijay Naidu PeddisettyvijayОценок пока нет

- I Have A Drone: The Implications of American Drone Policy For Africa and International Humanitarian LawДокумент24 страницыI Have A Drone: The Implications of American Drone Policy For Africa and International Humanitarian LawVarun SenОценок пока нет

- Natres Case Digest For FinalsДокумент3 страницыNatres Case Digest For Finalsnicole coОценок пока нет

- (Transformations of The State) Michael J. Warning-Transnational Public Governance - Networks, Law and Legitimacy (Transformations of The State) - Palgrave Macmillan (2009) PDFДокумент301 страница(Transformations of The State) Michael J. Warning-Transnational Public Governance - Networks, Law and Legitimacy (Transformations of The State) - Palgrave Macmillan (2009) PDFFrosina IlievskaОценок пока нет

- European Court of JusticeДокумент9 страницEuropean Court of JusticeElvedin FeratiОценок пока нет

- Remedies in International AdjudicationДокумент40 страницRemedies in International Adjudicationanshikasah12Оценок пока нет

- IMM5483EДокумент1 страницаIMM5483EErica CalzadaОценок пока нет

- During War The Law Is Silent or Is It - Examining The Legal StatДокумент31 страницаDuring War The Law Is Silent or Is It - Examining The Legal StatsapartisanОценок пока нет

- Your Document Checklist - Citizenship and Immigration CanadaДокумент4 страницыYour Document Checklist - Citizenship and Immigration Canadarussell_mahmoodОценок пока нет

- Application Form - Engine CadetДокумент3 страницыApplication Form - Engine CadetAllen AlonzoОценок пока нет

- The Treaty Office in A Nutshell: Contact ContactДокумент9 страницThe Treaty Office in A Nutshell: Contact ContactEnis LatićОценок пока нет

- Application Submitted: Appointment StatusДокумент1 страницаApplication Submitted: Appointment Statusprint arena0% (1)

- Russian Visa FormДокумент1 страницаRussian Visa FormSovereign TrackОценок пока нет