Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Framing of Climate Change

Загружено:

Juan Alberto CastañedaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Framing of Climate Change

Загружено:

Juan Alberto CastañedaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

449949

2012

PUS23210.1177/0963662512449949Bowe et al.Public Understanding of Science

P U S

Article

Public Understanding of Science

Framing of climate change 2014, Vol. 23(2) 157169

The Author(s) 2012

in newspaper coverage of the

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0963662512449949

East Anglia e-mail scandal pus.sagepub.com

Brian J. Bowe,Tsuyoshi Oshita, Carol

Terracina-Hartman and Wen-Chi Chao

Michigan State University, USA

Abstract

In late 2009, a series of e-mails related to climate research were made public following the hacking into

a server and the e-mail accounts of researchers at the University of East Anglia Climate Research Unit.

According to some skeptics of climate change research, the content of those e-mails suggested data were

being manipulated, while climate scientists said their words were taken out of context. The news coverage

of this scandal provides an opportunity to consider media framing. This study has two aims: to extend

previous research using a cluster analysis technique to discern frames in media texts; and to provide insight

into newspaper coverage of the scandal, which is often referred to as Climategate. This study examines

the frames present in two British and two American newspapers coverage of the issue.

Keywords

climate change, Climategate, cluster analysis, framing, newspapers

1. Introduction

In late 2009, a series of e-mails related to climate research were made public following the hack-

ing into a server and the e-mail accounts of researchers at the University of East Anglia Climate

Research Unit (CRU). According to some skeptics of climate change research, the content of

those e-mails suggested data were being manipulated, while climate scientists said their words

were taken out of context. Selected contents suggest the scientists had been manipulating or hid-

ing data, attempting to prevent publication of journal articles with which they disagreed, and fil-

ing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to their data. Key words include a hockey

stick graph, which CRU director Phil Jones reportedly asked to use to support specific time

periods that illustrated warming; he also referenced a trick in an analysis of tree ring data and

Corresponding author:

Brian J. Bowe, Michigan State University, School of Journalism, 305 Communication Arts & Sciences Building, East Lansing,

MI 48824, USA.

Email: bowebria@msu.edu

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

158 Public Understanding of Science 23(2)

in another message mentioned the need to hide the decline. Critics taking his comments out of

context accused the CRU and the entire field of climate science of being unethical.1 The news

coverage of this scandal provides an opportunity to consider media framing, which Reese (2001)

described as the way events and issues are organized and made sense of by media, media profes-

sionals, and their audiences (p. 7). This study is based on Matthes and Kohrings (2008) tech-

nique for discerning frames in media texts through a cluster analysis of frame elements. It uses

this technique to examine the frames present in coverage of the scandal, which is often referred

to as Climategate, in two British and two American newspapers.

2.Theoretical framework

As Tuchman (1980) suggested, news content functions like a window on the world through which

people learn of themselves and others, of their own institutions, leaders, and life styles, and those

of other nations and peoples (p. 1). Just like windows on houses, news content is contained within

a frame. In both cases, the construction of the frame itself alters what people are able to see and,

ultimately, how they make sense of it. This is the concept behind framing, which is an active area

of journalism and mass communication research (van Zoonen and Vliegenthart, 2011) and is the

most frequently used theory in top journals in the field this century (Bryant and Miron, 2004).

Framing has roots in sociology and was launched by Goffman (1974), whose work popularized

framing as a metaphor for studying the organization of social information in everyday life. This

type of framing involves the principles of selection, emphasis, and presentation composed of little

tacit theories about what exists, what happens, and what matters (Gitlin, 2003: 6).

Distinct from the types of framing present in everyday life, media frames, organize the world

for both journalists and the people who rely on their reports, offering a set of interpretive packages

that give meaning to an issue (Gamson and Modigliani, 1989: 3). Such frames provide the

persistent patterns of cognition, interpretation, and presentation, of selection, emphasis, and

exclusion, by which symbol-handlers routinely organize discourse, whether verbal or visual

(Gitlin, 2003: 7).

Yet, despite framings ubiquity or perhaps because of it the exact nature of frames

remains in question. Framing has been criticized for being undertheorized (Entman, 1993) or

even atheoretical (Matthes, 2009). In the literature, framing has been described as a concept, an

approach, a theory, a class of media effects, a perspective, an analytical technique, a paradigm,

and a multiparadigmatic research program (DAngelo and Kuypers, 2010: 2). Frames can be

operationalized as both independent and dependent variables (Carpenter, 2007), and they can be

found in the communicator, the text, the receiver and the culture (Entman, 1993). This very diver-

sity has at times pushed the field toward incoherence, with Reese (2007) offering the critique that

because of framings popularity, Authors often give an obligatory nod to the literature before

proceeding to do whatever they were going to do in the first place (p. 151).

Some researchers, acknowledging the problems with both reliability and validity in framing

research, have attempted to address those issues. One threat to validity in framing research is how

frames are operationally defined. Tankard (2001) stated that a crucial first step toward a systematic

empirical approach to framing research is the identification of common lists of frames for the

domains being discussed. Nisbet (2010) echoed that position, noting framing researchers have a

tendency to reinvent the wheel, when identifying frames, which leads to inconsistencies in

understanding both the nature and measurement of frames (p. 46).

In an effort to improve the reliability and validity of framing measures, this article builds on the

work of Matthes and Kohring (2008), who argued that a frame is a highly abstract concept, and that

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

Bowe et al. 159

coders are more reliable when coding smaller frame elements. They proposed and tested a method

that looks not for whole frames, but rather for separate frame elements, which they argue are more

easily coded in the material. After coding, researchers look for patterns among the frame elements.

That means when some elements group together systematically in a specific way, they form a pat-

tern that can be identified across several texts in a sample. We call these patterns frames (p. 263,

emphasis added). The method Matthes and Kohring proposed has been further validated by David,

Atun, Fille, and Monterola (2011), who determined that this procedure is efficacious for analyzing

highly complex issues that evolve over time.

3. Framing climate change

The issue of climate change provides an instructive case study for framing researchers because of

its tremendous complexity, transcending economic, political, scientific, and social boundaries

across cultures. Public attitudes toward the topic continue to reveal disagreement over whether

human-caused climate change is true, with public concern only recently recorded as rebounding

from all-time lows in the United States. As concerns over a warming planet grow, public skepti-

cism over human causes eases, but remains, in the United States and Great Britain (Jones, 2011;

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2011; Saad, 2009; Wan, 2010). The scientific

uncertainty surrounding climate change has been a major characteristic of coverage of the issue

since the mid-1980s, which Zehr (2000) argued erected a boundary between climate scientists and

the general public. The public depends on media to help them make sense of the science of climate

change (Boykoff, 2011), and media coverage can help amplify dramatic real-world events into a

full-blown scare (Ungar, 1992). However, Bell (1994) determined that even though reporters usu-

ally reported scientific issues correctly, one in six stories featured significant misreporting about

the scientific facts behind climate change.

Previous research suggests this disagreement continues to be reflected in the media coverage of

the phenomenon. But not only does the coverage reflect discord, it may contribute to it. As Antilla

(2008) noted, public perception of climate change is strongly influenced by media constructions of

the issue.

Because of American journalistic conventions, reporters are compelled to appear objective and

cautious and therefore, engage in self-censorship that causes them to either underreport aspects of

climate change or continue to posit a debate over issues the scientific community no longer finds

controversial (Antilla, 2005). In fact, Boykoff and Boykoff (2004) found it was the U.S. prestige

presss adherence to balance standards that led to biased coverage of human contributions to cli-

mate change and subsequent appropriate actions.

Another source of variation in coverage of climate change is the ideology of the media outlet

(Carvalho, 2007). Such ideologically driven frames which convey messages of scientific uncer-

tainty, economic consequences, and political conflict and strategy are more influential on public

perceptions of climate change than scientific consensus or mainstream news attention (Nisbet,

2010). Environmentalists tend to frame climate change as a looming disaster or within a Pandoras

Box frame a tactic that can lead to ridicule of scientists and public fatalism (Nisbet, 2010).

Opposing conservative groups counter that the science behind climate change is weak, that climate

change may offer benefits, and that efforts to counter climate change would do more harm than

good (McCright and Dunlap, 2000). Moreover, reporting on environmental issues has been found

to be shallow and biased in favor of corporate interests (Nissani, 1999).

Foust and Murphy (2009) examined two types of apocalyptic frames in the global warming

discourse: one rooted in cosmic fate and beyond human ability to control, and the other subject to

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

160 Public Understanding of Science 23(2)

human agency. The former approach, the authors claimed, provokes resignation in the face of a

human-induced dilemma (p. 164). But Iyengar and Kinder (2010) suggested audiences are more

engaged with episodic framing, which involves people and personalities as a chief storytelling

technique. Conversely, thematic framing, which offers a broader, societal discussion to abstract

concepts is less frequent (Iyengar, 1994, 1996).

When it comes to writing about an abstract, perhaps unobservable issue, such as climate change,

an unintended consequence of this trend might be, according to Hallahan (1999) that viewers and

readers feel absolved of responsibility for social problems because responsibility is so readily

attributed to the people portrayed in the news, whether or not the newsmakers depicted are culpa-

ble (p. 221).

4. Cross-national comparative study of framing

Framing research examines the way media and audiences organize and make sense of social phe-

nomena. Thus, it seems logical to expect differences in frames in different countries. Previous

research often emphasizes that differences in national media systems and news cultures can influ-

ence news media frames between nations (van Zoonen and Vliegenthart, 2011). However, scholars

have argued that more cross-national comparative studies are needed to further explicate those

relationships (Benson, 2004; Strmbck and van Aelst, 2010).

De Vreese, Peter, and Semetkos research on news coverage of the launch of the Euro (2001)

found that a conflict frame was highlighted in television news in all European countries they stud-

ied. Wittebols (1996) found clear differences in the tone of news coverage in the U.S. and Canada

in a study of news reporting on social protest, explaining such differences could be attributed to

structural variables, such as political systems and the countries position in the global society.

Snow, Vliegenthart, and Corrigall-Brown (2007) also found that other variables, such as time

and source use, exacerbated national differences. Furthermore, there is a suggestion that framing

does not localize at the national level and instead markedly differs from organization to organiza-

tion, and therefore, researchers should consider news production dynamics from organization to

organization (Archetti, 2008).

Comparative international research into media coverage of environmental issues (including

Brossard, Shanahan, and McComas, 2004; Good, 2008; Jones, 2009; Shih Wijaya, and Brossard,

2008) has produced mixed findings. Brossard et al. (2004) found that climate-related issues are

reported in culturally specific ways though such results dont suggest all newspapers or all

media within a given nation offer a similar social construction of an issue. Good (2008), refer-

encing Herman and Chomskys media propaganda model (1988), expected differences in cli-

mate change coverage as a result of societal factors influencing news production as well as the

role a system of government might play; she found U.S. papers were more likely to frame news

articles of climate change as discussions of science than were Canadian or international

newspapers.

Antilla (2008) found especially stark differences between U.S. and U.K. coverage of so-called

climate tipping points; however, in a study comparing news coverage of climate change in the U.S.

and Sweden, Shehata and Hopmann (2012) found striking similarities in coverage, suggesting

national political elites have minimal influence on how the issue is framed in coverage.

While primarily concerned with testing Matthes and Kohrings cluster analysis technique, this

study also contributes to the literature of cross-national comparative framing studies by examining

one research question and two hypotheses related to the coverage of the Climategate controversy

in the U.S. and U.K.

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

Bowe et al. 161

Previous research remains inconclusive on the question of whether one should expect a differ-

ence in media frames based simply on national differences. While the sample used in this study

cannot be generalized to represent the entire media landscape in the U.S. and the U.K., such uncer-

tainty inspired a research question:

RQ1: In examining a single media event, are the most dominant frames in British coverage different from

the frames in U.S. coverage?

However, because there is some support in the literature for the notion that media framing can

differ as a result of societal factors, this study tests a set of hypotheses based on the particularities

of the scandal itself and which of those particularities may have been more salient based on

national interests.

H1a: British coverage will frame Climategate as hackers responsibility more than American coverage.

H1b: American coverage will frame Climategate as scientists responsibility more than British coverage.

H2a: Climategate will be more often framed as a political issue in British coverage than in American

coverage.

H2b: Climategate will be more often framed as a scientific issue in American coverage than in British

coverage

5. Method

This study examines the framing of global climate change in two elite American newspapers and

two elite British newspapers coverage of the East Anglia e-mail scandal. Elite papers were selected

because they set the agenda for non-elite papers and tend to use more sources (Carpenter, 2007).

The frame elements were operationalized using Entmans (1993, 2004) definition of framing as the

emphasis of certain problem definitions, causal attributions, moral evaluations and/or treatment

recommendations in a communication text. Similar to Matthes and Kohring (2008), we considered

problem definitions to include both issues and actors. Causal attribution was operationalized as

whether the responsibility for the controversy was attributed to scientists or hackers. Moral evalu-

ation considered whether the issue was framed as scientific data manipulation or hacker criminal

behavior. Finally, treatment recommendation considered whether climate change was depicted as

true, false, or unknown. Heeding Nisbets advice about building on the work of previous research-

ers, portions of the coding protocol employed in this study were adapted from Trumbo (1996).

To determine the frames in media coverage of Climategate, this study examined newspaper

articles from two elite British newspapers (The Guardian and The Independent) and two elite

American newspapers (The New York Times and The Washington Post). Previous research has

shown that such elite or prestige newspapers set the agenda for other news organizations

(Reese and Danielian, 1989) and that quality newspapers tend to operate in nation-specific con-

texts (Strmbck and van Aelst, 2010). Boykoff and Boykoff (2004) similarly focused on prestige

press in the U.S. for a study of climate change reporting, while Carvalho (2007) examined the

British prestige press.

While the newspapers selected for this study are present in prior literature examining climate

change reporting, it should be acknowledged that the New York Times and Washington Post could

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

162 Public Understanding of Science 23(2)

be considered establishment media outlets, while the Independent and the Guardian are consid-

ered progressive. Thus, the papers on each side of the Atlantic would not likely attract the same

demographics. With recent literature suggesting a dominant frame of science in U.S. journalism

and enforcement/societal factors in U.K. reporting (Antilla, 2008; Carvalho, 2007; Good, 2008), it

is valuable to include these newspapers in the current study to further examine whether these same

frames would persist in coverage of a specific event, rather than discussion of a nebulous environ-

mental issue like climate change.

The New York Times and Washington Post are viewed as having a national voice per their

national distribution, but it is not the intent of this study to generalize results to all publications, not

even those with similar status, such as the Chicago Tribune or the Los Angeles Times. The U.K.

newspapers were selected for their appearance in prior literature, most notably Carvalho (2005,

2007). Studying climate change discourse in printed newspapers over 19 years, Carvalho and

Burgess (2005) argued that while sources, in particular the political authority figures, play a key

role in shaping the debate over climate change, the framing is mediated through each newspapers

distinct and individual ideological worldview.

The unit of analysis was the paragraph (n = 1,575), which allows for the discovery of more than

one frame per story. A sample was drawn via LexisNexis using the terms East Anglia and cli-

mate for four months from the date the story broke on November 19, 2009. The breakdown of

paragraphs by publication is New York Times (n = 272, 17.3%), Washington Post (n = 212, 13.5%),

The Independent (n = 440, 27.9%) and The Guardian (n = 651, 41.3%). A reliability test was con-

ducted on a randomly drawn subsample of 10% of the articles to determine intercoder reliability.

Using Scotts pi to correct for chance agreement, the reliabilities for the variables were as follows:

problem definition/issues (.78), problem definition/actors (.73), causal attribution (.74), moral

evaluation (.67) and treatment recommendation (.75).

6. Data analysis

To analyze the data, a cluster analysis was performed using Wards (1963) Method, which is a

procedure for creating hierarchical groups made up of mutually exclusive subsets that are based on

similarity. Punj and Stewart (1983) found it to outperform other clustering algorithms. As Matthes

and Kohring (2008) noted, this method is appropriate for identifying suitable cluster solutions in

this type of framing study.

Cluster analysis results are displayed in a tree-like diagram called a dendrogram. Upon visual

inspection of the dendrogram in this case, a four-cluster solution was deemed to be the best option

(Table 1), where best refers to the comparative value in comparison to a five-cluster and three-

cluster solution. The four-cluster results were saved as a variable in the dataset, so each observation

was labeled with its cluster membership. Table 2 breaks down the main variables in each frame.

Each of the four frames is described below.

The first frame we call a Scientific Dishonesty frame, comprised mainly of university scientists

(38.7%), political leaders (18.4%), and other scientists (15.5%). The causal attribution was almost

entirely (98.9%) scientists responsibility, and the moral evaluation was that Climategate was pri-

marily a data manipulation (82.9%). While the percentage was not large, this frame had the greatest

percentage of claims that climate change is not true (11.2%).

The second frame was similar to the first frame in some respects. This frames topic also was

mostly scientific (41.4%), with legal (15.1%) and political (14.5%) subtopics. As in the first

frame, the main actors included university scientists (23.3%) and other scientists (16.0%). Most

of the paragraphs in this frame did not make claims about causal responsibility (88.7%) or moral

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

Bowe et al. 163

Table 1. Results of four-cluster solution.

Four-cluster solution (Ward Method)

Frequency Percent Valid percent Cumulative percent

Valid 1 375 23.8 23.8 23.8

2 774 49.1 49.1 73.0

3 139 8.8 8.8 81.8

4 287 18.2 18.2 100.0

Total 1575 100.0 100.0

Table 2. Main variables for four frames.

Scientific Scientific Criminal Political

Dishonesty Explanation Activity Advocacy

frame frame frame frame

Issue: Scientific 66% 41.4% 26.6% 16.4%

Issue: Legal 5.3% 15.1% 58.3% 3.8%

Issue: Political 11.9% 14.5% 10.1% 56.1%

Actor: University scientists 38.7% 23.3% 27.3% 0.0%

Actor: Political leaders 18.4% 5.1% 7.9% 77.4%

Actor: Other scientists 15.5% 16.0% 9.4% 0.0%

Actor: Hackers 0.0% 0.8% 20.9% 0.0%

Responsibility: Scientists 98.9% 2.2% 2.2% 0.3%

Responsibility: Hackers 0.3% 0.0% 95.0% 0.3%

Responsibility: N/A 0.8% 88.7% 2.9% 99.3%

Moral: Data manipulation 82.9% 4.9% 6.5% 0.0%

Moral: Hacker crime 0.5% 2.0% 77.7% 0.0%

Moral: N/A 16.6% 93.1% 15.8% 100%

Treatment: Climate change is true 9.6% 20.3% 12.2% 38.2%

Treatment: Climate change is not true 11.2% 0.9% 5.0% 3.5%

Treatment: Truth of climate change unknown 35.2% 24.5% 26.6% 0.7%

Treatment: N/A 44.0% 54.3% 56.1% 53.7%

attribution (93.1%). While more than half of the paragraphs did not offer a treatment recommen-

dation (54.3%), the rest of the sample was split between claims that climate change was true

(20.3%) and that the truth of climate change was unknown (24.5%). We call this a Scientific

Explanation frame.

The third frames issue identification was largely legal (58.3%), with scientific (26.6%) and

political (10.1%) components. The largest numbers of actors in this frame were university scien-

tists (27.3%) and hackers (20.9%). The frame depicted the issue overwhelmingly as hackers

responsibility (95.0%) and as a crime by hackers (77.7%). The paragraphs that contained treatment

recommendations either claimed the truth of climate change is unknown (26.6%) or claimed

climate change is true (12.2%). We call this frame the Criminal Activity frame.

We call the fourth frame a Political Advocacy frame. More than half of the issues (56.1%) were

political and more than three-quarters (77.4%) of the actors were political leaders. This frame

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

164 Public Understanding of Science 23(2)

Table 3. Frame differences between U.S. and U.K.

U.S. papers U.K. papers

Scientific Dishonesty 114 (23.7%) 260 (23.9%)

Scientific Explanation 263 (54.7%) 507 (46.5%)

Criminal Activity 37 (7.7%) 102 (9.3%)

Political Advocacy 67 (13.9%) 220 (20.2%)

overwhelmingly lacked responsibility attributions (99.3%) and contained no moral evaluations.

Of the paragraphs that evaluated the truth of climate change, 38.2% suggested that climate change

is true.

To answer RQ1, we compared the difference between frames in American and British coverage

(Table 3) through chi-square tests of independence. Significant results were found for the Scientific

Explanation frame (2 = 4.454, df = 1, P = 0.0348) and the Political Advocacy frame (2 = 7.163,

df = 1, P = 0.0074). We failed to find, however, significant differences for the Scientific Dishonesty

frame (2 = 0.003, df = 1, P = 0.9553) or the Criminal Activity frame (2 = 1.061, df = 1, P =

0.3029). Those results indicate some difference between the American and British framing of the

controversy.

We conducted chi-square tests of independence on the causal attribution variables to test H1a

and H1b. On the question of whether British coverage would frame the controversy as hackers

responsibility more than American coverage, a significant result was not found (2 = 0.201,

df = 1, P = 0.6542). Likewise, on the question of whether American coverage would frame the

controversy more as scientists responsibility, we failed to find a significant result (2 = 0.101,

df = 1, P = 0.7507). Therefore, H1a and H1b were not supported.

The results for RQ1 could be seen to lend support for H2a and H2b. To further confirm, a chi-

square test of independence was conducted. A significant result was found on the question of

whether Climategate would be more often framed as a political issue in British coverage than in

American coverage (2 = 24.873, df = 1, P < 0.0001). Similarly, a significant result was found on the

question of whether Climategate would be more often framed as a scientific issue in American

coverage than in British coverage (2 = 29.554, df = 1, P < 0.0001). Therefore, H2a and H2b were

strongly supported.

7. Discussion

This articles primary concern was to discuss an emerging methodological approach to framing

research namely a manual-clustering frame analysis. The results of this analysis offer support

for the effectiveness of the frame coding method as described by Matthes and Kohring (2008). The

main advantage of this technique, these researchers note, is that frames are not subjectively deter-

mined but empirically suggested by an inductive clustering method (p. 275). By coding separate

frame elements, we were able to discern four coherent frames in just such a fashion. In this way,

we feel confident in agreeing with Matthes and Kohring that a frame is, indeed, a complex concept

that is the sum of its frame elements.

This study provides a snapshot of news coverage of Climategate from four elite newspapers in

the U.S. and the U.K. While the results of this study contribute to an overall understanding of the

differences in media coverage of Climategate, they offer only a part of the picture and are unable

to be generalized to all U.S. and British coverage. Still, it may be possible to speculate on

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

Bowe et al. 165

differences in coverage based on national interests. Perhaps H1a and H1b were not supported

because the question of whether Climategate was either scientific dishonesty or a crime perpetrated

by hackers doesnt have a binary answer it may have been both. Similar journalistic standards

in both nations may have dictated that both elements were part of the story.

On the other hand, H2a and H2b may have seen such strong support because they were not

related to what happened, but what it meant. In Britain, Climategate was more of a local story

because it involved public institutions and Parliamentary hearings over potential corruption. In the

U.S., on the other hand, the specific political implications of the situation were far removed, but the

general contours of the scandal fit into growing public skepticism of the scientific establishment.

The antecedents and effects of such frame differences need to be discussed from political,

economic, and journalistic contexts in further studies. In this sense, this study should be regarded

as a first step for such an expansive research project. By dissecting frames using this elemental

approach, researchers will be able to look more closely at aspects of frames among different

countries news coverage. In so doing, we believe the factors behind frame differences over time

can be analyzed.

In general, the results suggest news coverage did respond to the local particularities of the issue,

but that some frames crossed national boundaries. This further suggests that reporting on environ-

mental issues may be socially constructed and not only culturally constructed. Brossard et al.

(2004) discerned a stronger cyclical pattern in American coverage of climate change than in French

coverage, with U.S. reports focused more on domestic issues and conflicts between scientists and

politicians. Such patterns are related to well-established journalistic practices in U.S. media cul-

ture, and those patterns were present in this studys findings. But the most interesting results may

be the frames that crossed borders.

What is it about the Scientific Dishonesty and Criminal Activity frames that transcended

national media cultures? Perhaps the allegation of wrongdoing whether perpetrated by unethical

scientists or criminal hackers is more universally compelling and easier to understand than

explanations of complex scientific issues. These two frames seem to fit Iyengars (1994) descrip-

tion of episodic frames as illustrations of specific instances of events. Perhaps episodic frames are

particularly coherent in cross-cultural contexts.

On the other hand, the Scientific Explanation and Political Advocacy frames may be more

thematic in nature. Thematic frames report issues more broadly and abstractly by placing them in

some appropriate context historical, geographical or otherwise (Iyengar, 1996: 62). Because

the U.S. and U.K. have distinct social, political, and historical contexts, it would logically follow

that thematic frames might be less transferrable across cultures.

8. Limitations/future research

One of this studys main limitations was the lack of treatment recommendations. Of the four

frames, around half of the paragraphs had no treatment recommendation coded. Such a result may

mean that treatment recommendation should be operationalized in a different way; however, it also

may mean that treatment recommendation is a variable best measured at the story level, rather than

the paragraph level.

Another limitation was relatively low intercoder reliability on the moral evaluation variable.

Moral attributions were not as frequently occurring as some of the other frame element variables,

and that lack of variation was a blow to reliability when using Scotts pi to correct for chance agree-

ment. On a deeper level, though, this might bring into question Matthes and Kohrings assertion

that individual frame elements are inherently easier to code than holistic frames. Future researchers

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

166 Public Understanding of Science 23(2)

should continue to explore ways to improve the measurement of moral attributions in media texts.

Further, intercoder reliability was similarly cited as a limitation by Brossard et al. (2004), though

they suggested that it may have been a trade-off for greater validity.

This technique for determining frames holds promise, particularly when conducted at the

paragraph level. Future researchers should examine how many frames occur within individual

stories. They also should consider whether some variables are best examined at the story level,

rather than at the paragraph level. Finally, this technique should be expanded to other topics using

well-established codebooks to see whether the results are more reliable and valid.

Note

1. Two years after the initial hacking incident, a second round of hacking occurred, this time dumping

220,245 files onto a Russian server, and then onto skeptic Web sites. This pattern is a repeat of 2009, only

this time, investigators detected a message file that the perpetrator failed to encrypt. Despite assistance

from the Metropolitan Polices National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit and Qinetiq (a global

defense and security firm), to date, no one has been charged by the Norfolk Constabulary. Critics say

there has been little action on the matter.

References

Antilla L (2005) Climate of scepticism: US newspaper coverage of the science of climate change. Global

Environmental Change 15(4): 338352.

Antilla L (2008) Self-censorship and science: A geographical review of media coverage of climate tipping

points. Public Understanding of Science 19(2): 240256.

Archetti C (2008) News coverage of 9/11 and the demise of the media flows, globalization and localization

hypotheses. International Communication Gazette 70(6): 463485.

Bell A (1994) Media (mis) communication on the science of climate change. Public Understanding of Science

3(3): 259275.

Benson R (2004) Bringing the sociology of media back in. Political Communication 21: 275292.

Boykoff MT (2011) Who Speaks for the Climate? Making Sense of Media Reporting on Climate Change.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Boykoff MT and Boykoff JM (2004) Balance as bias: Global warming and the US prestige press. Global

Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions, Part A 14(2): 125136.

Brossard D, Shanahan J and McComas K (2004) Are issue-cycles culturally constructed? A comparison

of French and American coverage of global climate change. Mass Communication and Society 7(3):

359377.

Bryant J and Miron D (2004) Theory and research in mass communication. Journal of Communication 54(4):

662704.

Carpenter S (2007) U.S. elite and non-elite newspapers portrayal of the Iraq war: A comparison of frames

and source use. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 84(4): 761776.

Carvalho A (2005) Representing the politics of the greenhouse effect: Discursive strategies in the British

media. Critical Discourse Studies 2(1): 129.

Carvalho A (2007) Ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge: Re-reading news on

climate change. Public Understanding of Science 16(2): 223243.

Carvalho A and Burgess J (2005) Cultural circuits of climate change in U.K. broadsheet newspapers

19852003. Risk Analysis 25(6): 14571469.

DAngelo P and Kuypers JA (2010) Introduction: Doing news framing analysis. In: DAngelo P and

Kuypers JA (eds) Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives. New York,

NY: Routledge, pp. 113.

David CC, Atun JM, Fille E and Monterola C (2011) Finding frames: Comparing two methods of frame

analysis. Communication Methods and Measures 5(4): 329351.

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

Bowe et al. 167

De Vreese CH, Peter J and Semetko HA (2001) Framing politics at the launch of the Euro: A cross-national

comparative study of frames in the news. Political Communication 18: 107122.

Entman RM (1993) Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43(4):

5158.

Entman RM (2004) Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy. Chicago,

IL: University of Chicago Press.

Foust CR and Murphy WO (2009) Revealing and reframing apocalyptic tragedy in global warming discourse.

Environmental Communication 3(2): 151167.

Gamson WA and Modigliani A (1989) Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A construction-

ist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95(1): 137.

Gitlin T (2003) The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the New Left.

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goffman E ([1974] 1986) Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Boston, MA: North-

eastern University Press.

Good JE (2008) The framing of climate change in Canadian, American, and international newspapers: A

media propaganda model analysis. Canadian Journal of Communication 33: 233255.

Hallahan K (1999) Seven models of framing. Journal of Public Relations Research 11(3): 205242.

Herman E and Chomsky N (1988) Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media.

New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Iyengar S (1994) Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues, Paperback edn. Chicago,

IL: University of Chicago Press.

Iyengar S (1996) Framing responsibility for political issues. Annals of the American Academy of Political and

Social Science 546: 5970.

Iyengar S and Kinder DR (2010) News That Matters. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Jones AR (2009) Framing global warming: An international comparison of news media framing of climate

change from 19932003. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association,

San Francisco, CA, August 7. Available at (accessed November 10, 2010): http://www.allacademic.com/

meta/p307056_index.html

Jones JM (2011) In U.S., concerns about global warming stable at lower levels. Gallup.com. Available at

(accessed March 12, 2012): http://www.gallup.com/poll/146606/Concerns-Global-Warming-Stable-Lower-

Levels.aspx

Matthes J (2009) Whats in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in the worlds lead-

ing communication journals, 19902005. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 86(2):

349367.

Matthes J and Kohring M (2008) The content analysis of media frames: Toward improving reliability and

validity. Journal of Communication 58: 258279.

McCright AM and Dunlap RE (2000) Challenging global warming as a social problem: An analysis of the

conservative movements counter-claims. Social Problems 47(4): 499522.

Nisbet MC (2010) Knowledge into action: Framing the debates over climate change and poverty. In:

DAngelo P and Kuypers JA (eds) Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspec-

tives. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 4383.

Nissani M (1999) Media coverage of the greenhouse effect. Population & Environment 21(1): 2743.

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press (2011) Modest rise in number saying there is solid evidence

of global warming. Available at (accessed March 19, 2012): http://www.people-press.org/2011/12/01/

Punj G and Stewart DW (1983) Cluster analysis in marketing research: Review and suggestions for application.

Journal of Marketing Research 20(2): 134148.

Reese SD (2001) Prologue Framing public life: A bridging model for media research. In: Reese SD, Gandy

OH, and Grant AE (eds) Framing Public Life: Perspectives of Media and Our Understanding of the

Social World. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 731.

Reese SD (2007) The framing project: A bridging model for media research revisited. Journal of Communication

57: 148154.

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

168 Public Understanding of Science 23(2)

Reese SD and Danielian LH (1989) A closer look at intermedia influences on agenda setting: The cocaine

issue of 1986. In: Shoemaker PJ (ed.) Communication Campaigns about Drugs: Government, Media, and

the Public. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 4766.

Saad L (2009) Increased number think global warming is exaggerated. Gallup, March 11. Available at

(accessed March 19, 2012): http://www.gallup.com/poll/116590/increased-number-think-global-warming-

exaggerated.aspx

Shehata A and Hopmann DN (2012) Framing climate change: A study of US and Swedish press coverage of

global warming. Journalism Studies 13(2): 175192.

Shih TJ, Wijaya R and Brissard D (2008) Media coverage of public health epidemics: Linking framing

and Issue Attention Cycle toward an integrated theory of print news coverage of epidemics. Mass

Communication and Society 11: 141160.

Snow DA, Vliegenthart R and Corrigall-Brown C (2007) Framing the French riots: A comparative study of

frame variation. Social Forces 86(2): 385415.

Strmbck J and van Aelst P (2010) Exploring some antecedents of the medias framing of election news: A

comparison of Swedish and Belgian election news. International Journal of Press/Politics 15(1): 4159.

Tankard JW (2001) An empirical approach to the study of media framing. In: Reese SD, Gandy OH, and

Grant AE (eds) Framing Public Life: Perspectives of Media and Our Understanding of the Social World.

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 95106.

Trumbo C (1996) Constructing climate change: Claims and frames in U.S. news coverage of an environmental

issue. Public Understanding of Science 5: 269283.

Tuchman G (1980) Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York, NY; London, UK: Free

Press; Collier Macmillan.

Ungar S (1992) The rise and (relative) decline of global warming as a social problem. The Sociological

Quarterly 33: 483501.

van Zoonen L and Vliegenthart R (2011) Power to the frame: Bringing sociology back to frame analysis.

European Journal of Communication 26(2): 101115.

Wan KW (2010) UK grows more skeptical on climate change: Poll. Reuters, June 10. Available at

(accessed March 19, 2012): http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/06/10/us-climate-survey-idUSTRE

65968620100610

Ward JH (1963) Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American Statistical

Association 58: 236244.

Wittebols JH (1996) News from the noninstitutional world: U.S. and Canadian television news coverage of

social protest. Political Communication 13: 345361.

Zehr SC (2000) Public representations of scientific uncertainty about global climate change. Public

Understanding of Science 9(2): 85103.

Author biographies

Brian J. Bowe is a doctoral student in Michigan State Universitys Media and Information Studies

program and a graduate fellow in information and communication sciences at CELSAUniversit

Paris-Sorbonne. He is the author of several books about popular music. He holds a B.A. in journal-

ism and an M.S. in communications from Grand Valley State Universitys School of Communications,

where he previously served as a Visiting Assistant Professor.

Tsuyoshi Oshita is a doctoral student and a research assistant in Michigan State Universitys

Media and Information Studies program. Prior to joining the program, he worked as an advertising

media planner and a public relations consultant in Japan. He holds M.A. degrees in International

Public Relations from Cardiff University (U.K.) and Socio-Information and Communication

Studies from the University of Tokyo (Japan).

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

Bowe et al. 169

Carol Terracina-Hartman is a Research Assistant in the Knight Center for Environmental

Journalism at Michigan State University and a Visiting Assistant Professor of Mass Communications

at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania. As an environmental journalist, she worked in both

print and radio, in Wisconsin, Idaho and California. She holds a B.A. in English literature from the

University of Illinois U-C and an M.A. in Mass Communication from the University of

WisconsinMadison.

Wen-Chi Chao is an analyst at The Nielsen Company. She graduated from Michigan State

University with an M.A. in Public Relations.

Downloaded from pus.sagepub.com at UNIVERSIDAD C. SILVA HENRIQUEZ on October 19, 2015

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Sony x300 ManualДокумент8 страницSony x300 ManualMarcosCanforaОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Bumblebee SimpleДокумент8 страницBumblebee Simple文聪Оценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Role of Radio Lake Victoria in Enhancing Integration and Cohesion Among Residents of Border Two Sub-Location in Kisumu County, KenyaДокумент9 страницThe Role of Radio Lake Victoria in Enhancing Integration and Cohesion Among Residents of Border Two Sub-Location in Kisumu County, KenyaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- HDFC 25760Документ1 146 страницHDFC 25760kamlesha.apmp08Оценок пока нет

- Ken Verstaan Rekeningkunde Graad 11 OnderwysersgidsДокумент378 страницKen Verstaan Rekeningkunde Graad 11 OnderwysersgidsCharmaine Van WykОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Which Shoes Do You Choose?: by Aaron ShepardДокумент3 страницыWhich Shoes Do You Choose?: by Aaron ShepardFred Ryan Canoy DeañoОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- KJ JohnsonДокумент2 страницыKJ Johnsonapi-656761030Оценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Pornstar TW - Google SearchДокумент1 страницаPornstar TW - Google SearchskinnydoncashОценок пока нет

- Philco 46 451Документ2 страницыPhilco 46 451Alfredo SegoviaОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- RPT Bi KSSRPK Tahun 1 2021Документ9 страницRPT Bi KSSRPK Tahun 1 2021Norshatirah KassimОценок пока нет

- Service Manual: F H, /N1M, /U1MДокумент1 страницаService Manual: F H, /N1M, /U1Mdanielradu27Оценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Research PaperДокумент2 страницыResearch PaperAfaq ShabeerОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elementary Book Report: Frederick K.C. Price Iii Christian Schools Elementary Summer Book AssignmentДокумент1 страницаElementary Book Report: Frederick K.C. Price Iii Christian Schools Elementary Summer Book AssignmentlauОценок пока нет

- Communication Skills ObjectivesДокумент23 страницыCommunication Skills ObjectivesSharon AmondiОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- 3 Idiots Case StudyДокумент3 страницы3 Idiots Case StudycswaminathaniyerОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Ervice Manual: ST-CH510Документ14 страницErvice Manual: ST-CH510elezaregilsjaОценок пока нет

- Netspan Counters and KPIs Reference List - SR17.00 - Standard - Rev 13.4Документ122 страницыNetspan Counters and KPIs Reference List - SR17.00 - Standard - Rev 13.4br 55Оценок пока нет

- Sony Icf-703 703lДокумент12 страницSony Icf-703 703lSEC SemiconductorОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Editor Letter QuestionsДокумент3 страницыEditor Letter Questionsbhoomika mОценок пока нет

- Swot Pestle NetflixДокумент3 страницыSwot Pestle NetflixCriziajewel Resoles IlarinaОценок пока нет

- 2023 Fia Formula 1 World Championship - Accreditation Guidelines 0Документ9 страниц2023 Fia Formula 1 World Championship - Accreditation Guidelines 0Albert Sebastián MeyerОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Nonton Boruto Naruto Next Generations Episode 174 Sub Indo Gratis Download Dan Streaming Anime Subtitle Indonesia - Gomunime 2Документ1 страницаNonton Boruto Naruto Next Generations Episode 174 Sub Indo Gratis Download Dan Streaming Anime Subtitle Indonesia - Gomunime 2rizkydhs08Оценок пока нет

- Unit 3 PDFДокумент16 страницUnit 3 PDFTejaswi PundhirОценок пока нет

- Contenu Du Manuel Sony HVR-Z5E Service Manual (458 Pages)Документ3 страницыContenu Du Manuel Sony HVR-Z5E Service Manual (458 Pages)Andriamitantana ChristianОценок пока нет

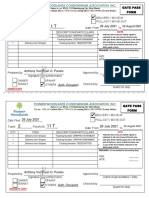

- GATEPASS - V3.0 PWL - 26 July To 02 August 2021Документ1 страницаGATEPASS - V3.0 PWL - 26 July To 02 August 2021Anthony Von Ryan PaneloОценок пока нет

- BUPATI CUP MALANG 2023 - EventsДокумент1 страницаBUPATI CUP MALANG 2023 - Eventssfcmn9ddr7Оценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- DLL - ENGLISH 4 - Q4 - W5 - Distinguish Among Types of Journalistic Writing @edumaymay@lauramos@angieДокумент14 страницDLL - ENGLISH 4 - Q4 - W5 - Distinguish Among Types of Journalistic Writing @edumaymay@lauramos@angieDonna Lyn Domdom PadriqueОценок пока нет

- Gameshark Pokemon RubyzafiroДокумент54 страницыGameshark Pokemon RubyzafiroWilper Maurilio Faya CastroОценок пока нет

- The Mentalist (TV Series)Документ10 страницThe Mentalist (TV Series)Larios WilsonОценок пока нет

- JulibeyДокумент3 страницыJulibeyJohn Exequel RaboОценок пока нет