Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Phnom Penh Education - Shivam

Загружено:

Rishi Garg0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

27 просмотров57 страницk

Оригинальное название

Phnom Penh Education- Shivam

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документk

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

27 просмотров57 страницPhnom Penh Education - Shivam

Загружено:

Rishi Gargk

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 57

The Royal Government of Cambodia has the

ambition to transition from a lower-middle

income country to being an upper-middle

income country by 2030 and a developed

country by 2050. The immediate and future

economic growth and competitiveness of

the nation to realize the ambitions depends

on our people having the right knowledge and

relevant skills, reflecting our cultural and

ethical heritage.

The education sector plays an important role

in the national development. The children,

youth and adults will receive education and

lifelong learning services with high quality,

which are relevant and responsive to the labor

market demand. In order to realize in full the

benefits of Cambodias demographic dividend

there has to be a focus on building skills for

learning and providing opportunities for

access to technical and specialized skills for

all.

The Education Strategic Plan (ESP) 2014-2018

has been designed to respond to these

demands and makes clear the relationship

between national policy and the education

policy. The Plan demonstrates a logical

relationship between the strategic framework,

programs, activities and both human and

financial resources. There is provision for

strong monitoring and evaluation, feedback

and adjustment to the plan if needed.

The Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport

(MoEYS) will continue to give a high priority to

equitable access for high quality basic

education services. The ESP 2014-2018 has

an increasing focus on the expansion of Early

Childhood Education, expanding access to

quality secondary and post-secondary

education and Non-Formal Education,

Technical and Vocational Education. Specific

measures will be taken to assure the

education for marginalized children and

youth. In order to provide focus,

accountability and clear outcomes the ESP

builds around seven key sub-sectors: Early

Childhood Education, Primary Education,

Secondary and Technical Education, Higher

Education, Non-Formal Education, Youth

Development and Physical Education and

Sport.

Within the context of decentralization,

providing the education system with the right

resources and the mechanisms to account

transparently is crucial to improving the

outcomes and impact of the education

activities. The ESP 2014-2018 includes

measures to improve the budget

management and to better linking results to

financial resources. Rigorous implementation

of the Teacher Code of Conduct, developing

the capacity of staff at all levels for effective

implementation against clear standards will

lead to better governance. In order to support

this, we will continue to implement the

strengthening of the partnership between the

Government and communities and parents,

the development partners, the private sector

and non-governmental organizations.

The ESP 2014-2018 has been developed in

the context of the National Strategic

Development Plan and as an evidence-based

response to the sector responsibility, taking

account of the reviews and analysis of the

previous ESP. There has been a rigorous

design process led by a High Level Task Force

and there have been wide national and sub

national consultations with the participation of

many stakeholders.

The Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport

would like to express appreciation to

education staff from all levels for their efforts

in overcoming the challenges and contributing

so fully to the implementation of education

reform. Also, thanks to all Development

Partners for their continuing technical and

financial support in the development and

improvement of education in Cambodia

Continued technical support is provided to the

MoEYS to the review the ESP and development of

the Annual Operational Plan (AOP) 2011. With the

request from the MoEYS, together with the Unit of

Education Policy and Reform (EPR) of UNESCO

Bangkok Office, UNESCO provides technical

support to and works closely with the team of

MoEYS Department of Planning in adapting the

existing Cambodian Analysis and Projection

(CANPRO) tool to include the budgeting framework.

It is expected by the MoEYS that this tool can be

used as a basis for planning and budgeting

formulation of all MoEYS sub-sectors. It can also be

used as the tool for negotiation with the MoEYS

Department of Finance, by the individual

departments, and as the negotiation tool with the

Ministry of Economy and Finance on budgeting. The

adaptation of this tool is expected to be ready for

dissemination in late 2011. Deputy/Heads of the

departments/Institutions, educational planners and

financial officers from both national and provincial

levels will be invited to the training workshops, which

will be facilitated by the experts from UNESCO

Bangkok Office (for the national level), and at

provincial level by the team of the MoEYS

Department of Planning who have been worked

closely with the experts from Bangkok Office.

. The author argues that during the 1950s and

1960s, efforts to enhance basic education

opportunities for all Cambodians were largely

unsuccessful due to the lack of adequate

infrastructural mechanisms and a guiding

framework for action. Of the periods

considered in this study, only the Prince

Sihanouk regime (1950s-1960s) was relatively

socioeconomically advanced, and saw a

growth in the number of modern school

buildings, teacher training centres, and

universities. The succeeding regimes in the

1970s not only failed to maintain the

development, but by the second half of the

1970s the formal education system had been

completely dismantled. The collapse in 1979

of the Pol Pot regime made way for the rebirth

of traditional socio-cultural structures and the

wide expansion of schooling opportunities

throughout the 1980s. National rehabilitation

and reconstruction during the 1980s, despite

lingering social insecurity, marked

considerable and fundamental progress

towards the present educational situation of

this struggling nation. Cambodia, basic

education, policy, strategy, educational

development INTRODUCTION The developing

world has made tremendous strides in

expanding primary education in the past three

decades, and many countries have achieved

universal primary enrolment. Most developing

countries are, however, still a long way from

achieving universal primary completion. With

their populations growing faster than primary

school enrolments, many countries will have

to make a vigorous effort to reduce illiteracy

over the next ten or fifteen years. Lockheed

and Verspoor (1991, p.37) Post-conflict

Cambodia is no different from the above-

described developing nations.

Notwithstanding its tragic past, namely, civil

conflicts and a massive destruction of socio-

cultural settings and human resources, led to

a serious social and educational crisis during

the 1970s and 1980s. Since gaining

independence from France in 1953, the ideal

policy of building a nation-state through

educational development was successfully

implemented. New schools were built

reaching to rural and remote areas; and

universities, which the French had refused to

offer during its colonial period (1863-1953),

were established in the capital and several

main provincial cities. The improved schooling

opportunities of the 1950s and 1960s were

expressly declined during the 1970s. It is

estimated that between 75 and 80 per cent of

the teachers and higher education students

fled or died between 1975 and 1979

(Klintworth, 1989 as cited in Asian

Development Bank, 1996, p.5). The

restructuring progression in education

systems and the overall social services in the

early 1980s marks the countrys

recommitment to socio-economic

development and expanding educational

opportunity. The schooling rehabilitation

process was rutted and obstructed by the Dy

91 continued social insecurity, especially in

the rural and remote areas. The Asian

Development Bank (1996) described the

educational situation during the 1980s as

poor school conditions, large numbers of

unqualified teachers, an absence of a national

curriculum framework, inadequate book

supply systems, and a high pupil dropout rate

in primary school. Nevertheless, Duggan

(1996) noted since the early 1980s that basic

education opportunity had been massively

expanded through the initiation of

comprehensive primary schooling strategies.

Since the 1990 Jomtien World Conference on

Education for All (WCEFA), Cambodian

leaders, especially in the late 1990s have

made numerous efforts to provide

accessibility for nine years of its currently

defined basic education, to all their citizens.

The contemporary regimes policy on

universal nine-year basic education of high

quality, which aimed to achieve before the

beginning of the twenty-first century, is

excessively ambitious (Dy and Ninomiya,

2003). A bunch of strategic approaches

employed to accomplish its profound goal of

basic education for all were barely, fully

implemented for the lack of funding and

disturbed social insecurity in several parts of

rural and remote areas during the 1990s

(ADB, 1996; Ayres, 2000; Dy, 2003; Prasertsri,

1996). Many of the targets for the year 2000

were not reached for several reasons such as

are found in insufficient number of schools,

financial burdens on the households,

insufficient learning and teaching facilities

which caused low enrolment and high dropout

rates within the basic education level. This

study covers Cambodias recent four regimes

of different political trends and ideology

dating from the 1950s to the 1980s

attempting to build, reform, adjust, and

transform the face of Cambodia from their

respective political strategies. The central

question begs to be asked here is what can an

examination of educational strategies and

policies of the pervious regimes of Cambodia

explain how basic education evolved and why

it was not fully enhanced? This paper traces

and analyses educational strategy and policy

development from 1950 to the period before

the 1990 WCEFA with a special concern on

basic education strategies and policies. This

period is critically significant for the history of

formal and mass modern schooling system

in Cambodia. It covers the very last few years

during the French colonial era, Prince

Sihanouk regime (1953-1970), Lon Nol regime

(1970-75), Pol Pot or infamous regime of the

Khmer Rouge (1975-79), and Heng Samrin

regime (1979-1989). It probes the regimes'

educational strategies and policies for their

citizens in line with the socio-economic

factors and their political trends. Their inputs,

methods, and outputs are discussed so as to

explain their commitments to building or

changing Cambodia. A modernization of the

Cambodian traditional education system,

done by the French, has lent support to socio-

economic development and building a nation-

state in the postcolonial era. This essay draws

extensively on chronological government

reports, ideas of other scholars, dialogues

with senior government education officials,

Khmer narratives and literature, and personal

memory and understandings. BACKGROUND:

KHMER TRADITIONAL EDUCATION SYSTEM

VERSUS THE FRENCH MODERN EDUCATION

SYSTEM Cambodian [Khmer] people were

among the first in Asia to adopt religious

concepts and sociopolitical institutions,

presumably from India, and to create a

centralized kingdom occupying large

territories in the present-day mainland South-

East Asia, with comparatively sophisticated

culture (Chandler, 1988; Encyclopedia

Britannica, 2001). This Indianized royal

headship regarded their religious leaders as

their intellectuals and guru (teachers), hence

this allowed the religious institutions to play

the role of educating their children and

people. The temple education practice was

first seen widespread in around the twelfth

century allocating the Buddhist institutional

92 Strategies and Policies for Basic Education

in Cambodia: Historical Perspectives system

of shaping the youth with Buddhist principles

about individual life, family, civil society, and

at least some basic literacy and numeracy

skills. This public schooling system could

allowably continue to provide only primary

education (Bit, 1991, p.50). The teachers were

volunteer Buddhist men (monks: sangha or

acharj). This traditional schooling system had

been implemented as early as the seventh

century for mainly the elite members in

society (Chandler, 1988). The system

escalated to the highest degree of education

in Buddhist Philosophy known as pundit or the

highest learning as noted by Chou, a Chinese

envoy to Angkor (former Cambodian capital)

during 1296-1297 (Chou, 1953). Bray (1999)

noted this long tradition of schooling financed

primarily from the contributions by villagers or

local community. This formal learning at the

temple schools were restricted to males for

one of the main reasons that the teachers

were Buddhist monks and the students were

required to stay and work at the temple. In

traditional education curricula, students were

taught sacred Khmer texts such as the Sutra

which contains the precepts of Buddhism,

literary traditions, and social life skills. The

principal aim of the temple schooling system

was to equip young men with the principles of

life and society such as social conduct, moral

ethics, as well as to achieve a certain degree

of basic literacy. The French colonized

Cambodia in 1863, but the colonial

government did not introduce a socalled

modern French schooling system until the

early 1900s. This introduction was mainly to

target the very few Cambodian elite

communities to serve the colonial powers

since the temple schools were only aiming to

sustain Khmer traditional culture. However, it

helped give for the first time, opportunity for

girls to have access to formal schooling. For

the first 20 years of their colony, Chandler

(1991) found the French had done so little to

interfere with traditional politics and even

neglected educational development in

Cambodia. In the early twentieth century, the

colonial administration began to modernize

the traditional schooling system by

integrating into the French schooling system,

arguing that Cambodias progress in more

cooperation and improved agricultural

production would serve better the colonial

power. Chandler (1998, p.156) commented,

Before the 1930s the French spent almost

nothing on education in Cambodia. The

French were reluctant to enhance education

for the idea that education would empower

Cambodians and tentatively bar Frances grip

(Clayton, 1995). Some scholars even argued

that the French purposefully withheld quality

education from Cambodians in order to

consolidate and then to maintain power.

French schools did indeed fail to enrol

significant numbers of Cambodians until late

in the colonial period. Several scholars (Ayres,

2000; Bray, 1999; Chandler, 1991; Clayton,

1995) see the modernization of the traditional

education system and the integration of the

French-oriented curriculum into the traditional

Khmer curriculum as a French socioeconomic

exploitation. Kierman (1985, p.xiii), as quoted

by Clayton (1995 p.6), argued: There were

160 modern [that is controlled by the French]

primary schools with 10,000 pupils by 1925

but even by 1944, when 80,000 [Cambodians]

were attending [some sort of] modern primary

schools, only about 500 pupils per year

completed their primary educationby 1944

there were only 1,000 secondary students

even by 1953 there were still only 2,700

secondary students enrolled in eight high

schools in Cambodia. Such a low investment

in modernizing Cambodian education is likely

because traditional Cambodian intellectuals,

especially the Buddhist monks, resisted the

Frenchs attempt to Romanize their traditional

language scripts in the 1940s as the French

had successfully done to the Vietnamese

(Chandler, 1998; Osborne, 1969). Seeing that

their traditional culture of education on Dy 93

the verge of collapse caused by the French

reform, the Cambodians resisted and even

actively opposed the French reform in rural

areas (for discussion see Clayton, 1995).

EVOLVING CONCEPTS OF EDUCATION AND

BASIC EDUCATION From a traditional, social

and cultural perspective, education is

literally defined by Cambodians on one hand

as an honest route to better the human

condition, intentionally aimed at shaping

individuals for a better lifestyle, knowledge,

and good manners for living in their

respective societies. On the other hand, the

contemporary Cambodian perception of

education refers to a process of training and

instruction, especially of children and young

people in schools, which is designed to give

knowledge and develop skills. Both induct the

maturing individual into the life and culture of

the group. This consciously and purposefully

controlled learning process is conducted by

more experienced members of society. In

traditional education the pupils received

instruction in the arts of writing, ethical

precepts, practical philosophy, and good

manners. There were also traditional codes of

conduct and rules (chbab) for men and

women requiring them to learn and obey to

become good members of the Khmer family

and society. Thus basic education, as a

minimally adequate level of education to live

in society is varied in accordance to socio-

cultural and socio-political factors of the state.

The majority of Cambodians are peasants

relying on subsistence agriculture.. What

should be an adequate level of basic

education that Cambodian citizens should be

equally equipped? The 1990 WCEFA identified

basic education as aimed at meeting basic

learning needs. Hence, the length of formal

education and education content should

depend on the policy of the individual society

or country. With reference to this definition,

Cambodian basic education was identified in

the 1950s and 1960s as at the primary

education level in urban areas and at basic

literacy level (being able to read and write

everyday-life texts) in rural areas (Ministry of

National Education, 1956-57). The level of

education, which should be appropriate to

meet basic learning needs during this period

was unclear. In the mid-1980s the

government started its commitment to

strengthening the quality of educational

provision. Education officials noted that during

the 1980s, basic literacy or at least

completion of the fourth grade of the primary

cycle (then five years in length) was sufficient

for achieving basic education. ENHANCING

BASIC EDUCATION OPPORTUNITY: 1950-60 In

the last few years before the French left

Cambodia, the colonial government, with

recommendations from UNESCO, grudgingly

introduced compulsory education for children

aged 6 to 13 years. Events during these years

have shown that the effort to provide

compulsory, free primary education was too

hasty. In the report presented at the UNESCO

14th International Conference on Public

Education, Princess Ping Peang Yukanthor in

1951 stated: The principle of compulsory

education can thus not be fully applied until

the government is in a position to fulfill its

essential duties through the possession of 94

Strategies and. Prince Norodom Sihanouk was

crowned King of Cambodia by the French

colonial power in 1941 when he was still a

senior high school student at a French Lyce

in southern Vietnam. His policies for education

after gaining independence were to attain the

goal of compulsory primary education for all

and to increase, at all levels of educational

opportunities from primary to university

institutions. His efforts were to build a

prosperous nation-state through educational

development. New principles of educational

development in the 1950s, with the

recommendations from UNESCO, were

introduced and some were fully implemented

such as increasing more learning

opportunities for boys and girls and fighting

illiteracy among adults in rural areas.

However, the achievement was far from

satisfactory. Statistically, only 10 per cent of

female adults were basically literate in 1958

(Peng Cheng Pung, 1959. By the late 1960s,

more than one million children enrolled in

primary education as compared with about

0.6 million in 1960 and 0.13 million in 1950.

From 1950 to 1965 the number of females

enrolled at the primary level grew from 9 per

cent to 39 percent. The number of teachers

and schools has expanded commensurately

from 1950 to 1964. Although primary

enrolment rate increased, the illiteracy rate

was estimated 50 per cent in 1953 for a

population of 3.7 million and at 55 per cent

for a population of 6.2 in 1966. Reflecting its

attention and commitment to formal

education in building a modern and peaceful

state, the regime even increased national

budget for education to over 20 per cent of

the national expenditure by the late 1960s.

the regime had failed to universalize basic

education and enhance employment for high

school and university graduates. Thus,

Duggan (1996, p. 364) criticized the regime:

The education system provided by Sihanouk

was biased towards the nations large cities.

Rural Cambodia did not benefit from the

selective expansion strategies employed by

the Prince (Sihanouk) and handsomely built

universities did not assist rural children and

their familys poverty. Despite criticisms of the

regime for not having enhanced nationwide

literacy-oriented education or increasing

quality schooling opportunities for all, the

regime marked a great recovery of Cambodia

in the past few hundred years of its history.

Dunnett (1993) claimed that during the

1960s, Cambodia had one of the highest

literacy rates and most progressive education

systems in Southeast Asia. Dy 95 The belief

that enhanced education would bring the

benefit of higher employment in the

government sector was raised in these works,

which was also subsequently reflected in

school curriculum. The social value of

furthering the education of the individual,

leading to a better future, was closely

associated with the increased development of

higher education institutions in the larger

cities. However, the failure to give top priority

to basic education during the 1960s led to the

crisis in education system (for further

discussion see Ayres. During the early 1970s

Cambodia was inevitably drawn into the

Vietnam War. The national instability and

political turmoil led the Lon Nol regime to

reduce educational funding and many school

closed in rural areas. Simultaneously, many

teachers fled to join the Khmer Rouge

movement while student and teacher

demonstrations frequently occurred in Phnom

Penh. SCHOOLING ABOLITION: 1975-79

Cambodia was eventually plunged into a

complete darkness during the regime of

Democratic Kampuchea, or the infamous

Khmer Rouge, locally known as the Pol Pot

regime which came into power in April 1975.

The regime led Cambodia into revolutionary

Maoist communism. Pol Pots so-called great

leap revolutionary regime further ravaged

Cambodia through the mass destruction of

individual property, schooling system, and

social culture by forcing the entire population

either into the army camps or onto collective

farms (Chandler, 1998; Dunnett, 1993).

Damage was inflicted not only to the

educational infrastructure, but Cambodia also

lost almost three-quarters of its educated

population under the regime when teachers,

students, professionals and intellectuals were

killed or managed to escape into exile (ADB,

1996; Prasertsri, 1996). During the early years

of this regime, basic education was deemed

unnecessary since almost all citizens were

working in factories and farms (for

EDUCATIONAL REHABILITATION AND

RECONSTRUCTION: 1979-1989 Peoples

Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) or Heng Samrin

regime (1979 to 1989) started to rebuild the

country. The regimes top priority between

1979 and 1981 was to reinstall educational

institutions. Generous support from UNICEF

and International Red Cross, together with a

strong determination to restructure Cambodia

by the PRK, saw about 6,000 educational

institutions rebuilt and thousands of teachers

trained within a very short period (Dunnett,

1993). According to an interview with a senior

education official who had been involved in

basic education system and teacher training

since 1979, the regimes policy on enhancing

education was: 1979-1981 was a period of

restructuring and rehabilitating of both

infrastructure and human resources. By

restructuring and rehabilitation I refer to

collecting school-aged children and putting

them into schools despite in the poor

condition. Classes were even conducted in

makeshift, open-air classrooms or under trees.

We appealed to all those surviving teachers

and literate people to teach the illiterates. We

used various slogans such as going to teach

and going to school is nation-loving and so

on. There were no official licences or any

requirements for taking on the teaching job.

We just tried to open schools and literacy

classes, regardless of their quality. The rebirth

of education in Cambodia in 1979 represents

a historically unique experience from that of

any other nations. In the early 1980s, all

levels of schooling (from kindergarten to

higher education) were reopened and the

total enrolment was almost one million. Many

teachers were better trained and quality

gradually enhanced. Enrolment in primary

education in 1989, increased to 1.3 million,

and in lower secondary to 0.24 million,

compared with only 0.9 million and 4,800 in

1980 (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport,

1999). However, it is worth noting that in any

primary school, about 30 per cent of the

children had no father, 10 per cent had no

mother, and between 5 and 10 per cent were

orphans (Postlethwaite, 1988). The political

and economic disturbance haunted Cambodia

pending the second term of the current Royal

Government and the complete eradication of

the Khmer Rouges machinery and

organization in 1998. Nevertheless, the

people of Cambodia still have pride and look

forward to a golden age when their nation will

again be prosperous. CONCLUSION Social and

political factors of the last four decades from

the 1950s to the 1980s determined the flux of

crisis and progress of the schooling systems.

The former extensive Khmer Empire,

Cambodia suffered massive socio-cultural

destruction, political turmoil, genocide,

international isolation, and socio-economic

crisis during the civil conflicts of the 1970s

and 1980s. Political and economic problems

during the above two decades were not

isolated from the education structure, which

was also seriously damaged during the civil

conflicts. Shifting from limited or no access for

girls to formal education within the traditional

school system to the French schooling system

in the early twentieth century was a positive

step towards universal basic education.

However, although primary education was

made compulsory in the 1950s and 1960s,

there was no presence of mechanism in

handling the implementation of the policy. The

changing concepts of basic education from

basic literacy to primary education, and to

primary plus lower secondary education in the

mid 1990s saw the expansion of learning

opportunities for better lifestyle and socio-

economic amelioration in contemporary

Cambodia. The experiments of the 1950s and

1960s were largely unsuccessful because

modern educational contents and outcomes

could not meet the actual needs of the society

at that time. In other words, many

Cambodia has made significant improvements in

education over the last years. The Ministry of

Education, Youth and Sport (MOEYS) is close to

achieving universal access to primary education; the

country achieved a 98 percent primary net

enrollment rate in 2015. Cambodia has also

strengthened gender parity in education, with girls

comprising 48 percent of primary students.

Cambodia has built nearly 1,000 new schools in the

last ten years and has invested significant resources

to expand access to a quality education. The

government has committed 18 percent of the

national budget to education. Between the years

2010 - 2014, the government revised the national

curriculum and corresponding student learning

materials with the goal to improve learning. Despite

these gains, Cambodia has one of the highest pupil-

to-teacher ratios in the region and only 53 % of third

graders are reading at grade level.

ACTIVITIES

Early Grade Reading Analyses and

Capacity Building

To inform and expedite start-up for a new Early

Grade Reading (EGR) program, USAID conducted a

comprehensive early grade reading sector

assessment in 2015.

The EGR Sector Assessment identified

specific technical areas where USAID could

provide immediate support to strengthen

MoEYS systems, tools and capacity. During

2016, USAID has supported bridging

activities to build MoEYS capacity to

develop and manage early grade reading

assessment tools and processes. This

support will help the MOEYS to have

reliable and valid tools and assessment

procedures to measure early grade reading

skills.

In collaboration with the MoEYS Primary

Education and Education Quality Assurance

Departments, USAID provided technical

assistance to update the 2009 early grade

assessment tool and pilot tested the new

instrument in selected schools.

Support for Senior MoEYS Engagement

on Global Education Policy Dialogue

Over the past year, USAID supported three MoEYS

delegation visits to the U.S. to engage on global

education policy dialogue and see different U.S.

models for school management and education

service delivery. Senior MoEYS officials participated

in the School Drop-out and Prevention Summit, the

USAID Global Education Summit and, most recently,

were invited to present on early grade reading

assessment to commemorate International Literacy

Day 2016 at the Library of Congress in Washington,

D.C

Education in Cambodia

Early 1900

Education progressed very slowly in Cambodia. The

French colonial rulers did not pay attention to educating

Khmer. It was not until the late 1930s that the first high

school opened. However, after gaining independence from

France, the government of Prince Norodom Sihanouk

made substantial progress in the field of education in the

1950s and 1960s. Elementary and secondary education

was expanded to various parts of the country, while higher

learning institutions such as vocational institutions,

teacher-training centers and universities were established.

Unfortunately, the progress of these decades was

obstructed by the Khmer Rouge regime.

Education & Khmer Rouge

During the regime of the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to

1979, education in Cambodia was the first one to be

disintegrated by Pol Pot's Communist leaning

government. Back then, schools nationwide were ordered

to be closed. Teachers were among the first victims of the

Khmer Rouge's purging as they radically were preparing a

massive indoctrination program for the youth. In fact,

90% of the teachers that time were killed while the rest

fled the country or stayed in anonymity.

Education & occupation Vietnam

Vietnam, who occupied Cambodia in 1980 as a result of

Pol Pot's transgressions into Vietnamese territories,

slowly re-integrated education. However, not all were

able to able to gain access to the new educational system

but was only available to children of civil servants. One

catch also during that time was that lessons were biased to

the Vietnamese culture.

Current situation education

Currently, post-Vietnam occupation and back to the

Cambodia's monarchial rule, education has improved

greatly. The constitution now promulgates a compulsory

education for everyone. All eligible students have free

access to education for nine years. However, as much as it

is put into law, providing this basic service is not widely

enforced.

Problems like lack of qualified teachers, low student

attendance in the rural areas still persist. There are not

many who are willing to teach as salary and benefits are

unattractive while students from the rural areas prioritize

helping their families cultivate the fields.

Daily challenges

The daily realities for both teachers and students in the

Cambodian education system are very challenging.

Teachers face inadequate salaries and the need to charge

students fees for services. Students face inadequate

facilities, large classroom size, sometimes travel times to

nearby villages or towns, and high costs for their families.

At the upper levels these problems are compounded by

the need to pay bribes to pass the upper secondary level

exams and to secure admission to universities. This is one

factor that has contributed to the growth in private sector

education.

Literacy, knowledge and development

Presently, Cambodia still has a high illiteracy rate where

76.25% of men and 45.98% of the women have yet to

know their ABCs. The Ministry of Education Youth and

Sport has a strategic plan in place and have already

launched programs like the National Development

Strategic Plan 2006-10, Cambodia Millennium

Development Goals, and the Education for All National

Plan 2003-2015 to give Cambodian children hope for a

brighter future.

empowering Youth in Cambodia is a

grassroots organization based in Phnom Penh,

Cambodia working to improve the lives of

young people and their families. Our vision is

to see youth empowered with skills and

confidence to be leaders who actively develop

themselves, their families and the community

for positive change.

Most students study in a public primary

school, high school or university, as well as

work to support their studies. During the

morning and afternoon the younger students

come to study basic English, health and life

skills before or after school. In the evenings

the students are mostly teenagers who are in

high school. The students must live in the

community to qualify to study at the school,

unless given special permission.

http://eycambodia.org/ donation website

EYC currently runs 4 learning centers, operating as

combined schools and community centers, in Phnom

Penh poverty-stricken communities. The schools are

houses that we rent in a price range of approximately

$100-$200 per month, each with a classroom and small

computer lab. Each of the schools has roughly the same

curriculum:

Mornings and afternoons are classes for

children (aged 6 to 13 years old) with

some English classes, hygiene lessons,

art, sports, and games.

Evenings have 3 different levels of English

for youth, generally aged 14 to 24, as well

as some health, life skills, and leadership

training.

Computer skills are taught throughout

each day, into the evening.

On weekends, each school runs a variety of activities

including sports, leadership seminars, Youth Leadership

Challenge, community organizing, youth legal rights,

yoga, dancing, aerobics, art and an IT Forum.

In this post, Sokhan Khut, Country Manager for

Cambodia at BOOKBRIDGE, gives a short

introduction to the Cambodian Education System.

In Cambodia, an education system has been in place since

at least from the thirteenth century on. Traditionally,

Cambodian education took place in the Wats (Buddhist

monasteries) and was offered exclusively to the male

population. The education involved basic literature, the

foundation of religion and skills for daily life like

carpentry, artistry, craftwork, constructing, playing

instruments etc.

This traditional education was gradually changed when

Cambodia was a French colony (1863-1953). The French

introduced a formal education system influenced by a

Western educational model, which was developed through

the independence period (1960s), alongside with the

traditional education. During the following civil wars, the

education system suffered a chronic crisis and was

completely destroyed during the Red Khmer regime

(1970s). Between 1980s and 1990s, education was

reconstructed from almost nothing and has been

gradually developed until now.

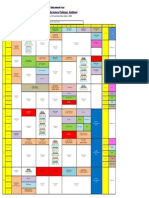

Presently, after its reform in 1996, the formal educational

structure of Cambodia is formulated in 6+3+3. This

means 12 years for the completion of general education

that divides up into six years for primary education (grade

1 to 6) and six years for secondary general education

(grade 7 to 12). Secondary education consists of three

years each for lower secondary education (grade 7 to 9)

and upper secondary education (grade 10 to 12). This

formulation does not include at least one year for pre-

school education (kindergarten) for children from 3 to

below 6 years old and universitary education of 4 to 5

years.

Two others components of Cambodian educational

structure involve non-formal education providing all

children, youth, adult, disabled people with literacy and

access to life skills. The other component is teacher

training education. This allows students that successfully

completed grade 12 or grade 9 to pursue teacher

certificates at provincial teacher training colleges (for

primary school teachers) or regional teacher training

centers (for lower secondary school teachers).

Currently, the educational system is run by the

Cambodian state, but private education exists at all levels

and is run by private sectors. Most private schools

offering pre-school education and general education have

been operated by the communities of ethnic and religious

minority including Chinese, Muslim, French, English and

Vietnamese. Private higher education is accessible mainly

in the capital of the country, but it is also available

throughout the provinces of Cambodia.

Cambodian general education is based on a national

school curriculum that consists of two main parts: basic

education and upper secondary education. Basic

education curriculum is divided into three cycles of three

years each. The first cycle (grade 1-3) consists of 27-30

lessons per week lasting 40 minutes which are allocated

to the five main subjects:

Khmer (13 lessons)

Maths (7 lessons)

Science & Social Studies including Arts (3 lessons)

Physical and Health Education (2 lessons) and local

life skills program (2-5 lessons)

The second cycle (grade 4-6) comprises of the same

number of lessons but is slightly different:

Khmer (10 for grade 4 and 8 for grade 5-6)

Maths (6 for grade 4-6)

Science (3 for grade 4 and 4 for grade 5-6)

Social Studies including arts (4 for grade 4 and 5 for

grade 5-6)

Physical and Health Education (2 for grade 4-6)

Local life skills program (2-5 for grade 4-6).

The third cycle (grade 7-9) consists of 32-35 lessons

which are allocated for 7 major subjects:

Khmer

Maths

Social Studies and Science (6 lesson respectively)

Foreign languages (4 lessons)

Physical & Health Education and Sports (2 lessons)

Local life skills program (2-5 lessons)

Upper Secondary Education curriculum consists of two

different phases. The curriculum for the first phase (grade

10) is identical to the third cycle of primary education

(see above). The second phase (grade 11-12) has two

main components: Compulsory and Electives.

Compulsory involves four major subjects with different

numbers of lesson allocated per week: Khmer literature (6

lessons), Physical & Health Education and Sports (2

lessons), Foreign language: English or French (must

choose one, 4 lessons each) and Mathematics: Basic or

Advance (must choose one, 4 or 8 lesson respectively).

Electives include three major subjects covering four or

five sub-subjects with four lessons allocated per week for

each one (students may choose one or two or three of

them):

Science: Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Earth and

Environmental Studies

Social Studies: Moral/Civics, History, Geography,

Economics

EVEP: ICT/Technology, Accounting Business

Management, Local Vocational Technical Subject,

Tourism and Arts Education and other subjects

For those choosing Basic Maths or Advance Maths must

choose four sub-subjects or three subjects respectively

from the electives.

t. There are three ways of providing and receiving

education: formal, non-formal and informal. The formal

education structure consists of pre-school education six

years of primary school (grades 1-6) where pupils should

be enrolled at the age of six, three years of lower-

secondary school (grades 7-9) and three years of upper

secondary school (grades 10-12). For the academic year

2009-2010, the total number of students was 3,248,479

(1,540,077 female) and the number of educational staff

94,723. We had 10,115 schools with a total of 80,508

classrooms. With the improvement in the national

economy, especially in the capital of Phnom Penh,

education has become a more valuable commodity and

private schools were opened.

For those who have dropped out of school without

completing the basic education level (grades 1-9), there

are opportunities to attend literacy and life-skill

programmes as well as short-term vocational training

programmes offered by the MoEYS, Ministry of Women

Affairs (MoWA) and Non Governmental Organisations.

After completing lower-secondary education, students

have the option of continuing to upper-secondary

education or of entering secondary-level vocational

training programmes offered by the Ministry of Labour

and Vocational Training (MoLVT). After completing

upper-secondary education, students enter vocational

training or tertiary education.

For teacher training, currently there are 18 Provincial

Teacher Training Colleges (PTTCs) for primary school

teachers, 6 Regional Teacher Training Colleges (RTTCs)

for lower secondary school teachers, 1 National Institute

of Education (NIE) for upper secondary school teachers

and 1 Pre-school Teacher Training Center for pre-school

teachers.

Since 2000, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport

(MoEYS), with support from UNESCO and other

partners, has embarked on a policy-based sector-wide

reform, guided by a five year Education Strategic Plan

(ESP) designed to accelerate achievement of Education

for All (EFA). This has been a challenging process,

requiring extensive research and analysis of sector

performance and trends in order to formulate new reform

policies and strategies based on the existing educational

major policies: to universalize 9 years of basic education

and developing opportunities for functional literacy; to

modernize and improve the quality of education through

effective reform; to link education/training with labour

market and society; to rehabilitate and develop youth and

sport sub-sector.

children in Cambodia have many barriers standing

between them and a great education. Poverty is one

problem, but so is a lack of education spending in this

country and the endemic system where even state schools

charge students each month to help cover saalries and

other expenses. The objective of Savong's School is to

provide free education, the necessary teaching resources

for teaching, and the opportunity for the best students to

proceed to university.

In Cambodia 12.4% of government spending is in

education

Of Cambodia's 14.4 million people, half are under

age 22 - and so there is a burgeoning school age

population. Education statistics are improving

dramatically but are still very low by world standards.

By the end of 2010 the Cambodian Government

acknowledged that foreign-funded schools were an

integral and necessary part of the education system: a tacit

admission that it was unable to meet the costs of such a

system by itself. Likewise, foreign-funded NGOs face

strict ultimatums if they criticise the Government.

Education facts and figures: Cambodia

Primary School Data

Net primary school enrolment ratio - The number of

children enrolled in primary school who belong to the

age group that officially corresponds to primary

schooling, divided by the total population of the same

age group.

Males 93%

Females 90%

Net primary school attendance - Percentage of

children in the age group that officially corresponds to

primary schooling who attend primary school. These

data come from national household surveys.

Males 73%

Females 76%

A UNESCO estimate is that 10% of eligible primary

students currently do not attend school.

Primary school entrants reaching grade five -

Percentage of the children entering the first grade of

primary school who eventually reach grade five

(equivalent of age 10 or 11 in western schools.)

56% (admin figures)

95% (survey figures.) Take your pick!

World Bank figures suggest that in 2006 some 87%

of students who begin primary school complete

primary school. Among those below the poverty line

however - with family incomes below $US30 per

month - 65% complete primary school. Both results

were significant improvements over the 1999-2000

figures.

Student to teacher ratio in primary schools.

According to World Bank figures there are 50

students per teacher.

Secondary School Data and Tertiary

World Bank figures for 2006 suggest that 79% of

primary students progress to secondary school.

28% of girls and 33% of boys are in secondary

school. (UNESCO) These figures have doubled since

1999.

There is one secondary teacher for every 28 students.

(World Bank data.)

75.6% of adults and 85.3% of youth (15-24) are

literate.

According to UNESCO 5% of the population of

tertiary age are in tertiary education.

Education is very important means to train and build up

human resources for development of each country and it

is also important for development of child as person. After

that period, the government has tried to improve it by

cooperated and collaborated with external aid and non-

governmental organization (NGOs). According to the

Cambodian constitution, it states that "the state shall

provide free primary and secondary education to all

citizens in public school. Citizens shall receive education

for at least nine years". Nowadays, though the pupils have

no pay the fee, they still have to spend money on other

things such as stationery, textbooks, contribution fee etc.

Moreover, some provinces students are asked to spent

money to teacher for fee; this is the problem that prevent

pupil from poor families from attending school.

About a half a million Cambodian children from 6 to 11

years old have no access to school, then 50percent of

those who entered grade one dropped out of school and

had to repeat the class., and for female pupils, they could

not attend school because of many problems. First,

parents are poor, so they cannot provide children to learn

and sometime they need their children, especially the

girls, to earn money to support the family. Second, the

schools are located too far away from their house. Only

boy can go to school at some distance from home because

they have given accommodation in pagodas near the

school. The last one is some parents do not understand

about the important of education, so they do not allow

their children to attend school.

Moreover, the ministry of education has not provided

adequate education for minority children. Many children

cannot access to school, and there is no provision for

schooling in minority languages except for classes

provided by private ethic associations. Not only that, there

is insufficient special education provision for disabilities

children. Even though some organizations co-operated

with government to provide school for those, this effort is

not yet enough. Then, the quality of education in

Some schools in urban areas have around 60 to 80

students in each class, because there are not enough class

for pupils, most schools operated two shifts or three shifts

per a day that affect the pupils' feeling to study . Other

thing is that the limited skilled of teachers reduce the

quality of educational system. Technical and pedagogical

training for teacher is not up to standard yet. There are

many teaching methods such as child-centered learning

method has been taught to some teachers; however,

teachers still follow the old teaching methods. The last

point is the lack of commitment of teacher because they

receive a small amount of salary) that lead to the low

motivation for teaching. Then, they need to find others job

to supplement their incomes for survival. In fact, the

national government budget allocation to Ministry of

Education, Youth and Sport was only 10.3% in 1997 and

increase to 12% in 1998, which is still very, in particular

when compared to 52% for the defense sector.

The government should pay more attention because this

sector is the major sector for development the country.

Government should provide the high salary to teachers,

and build more school all around the country, and national

budget allocation for education should be increased

promote and facilitate the education to minority children

and provide special school for disabled children and

promote education for girls, raise awareness of parents

about the advantage of education. Finally, the educational

system in Cambodia has faced many problems that have

to solve immediately. Those problems can be affected on

development for country as well.

. United Nations Organization is an international

organization that aim are facilitating collaboration in

international law, international peace and security, human

right, economics development, social progress and

achieving world peace

First, UNDP is the UN global development network. It

promotes for change and connects countries to

knowledge, experience and resources to help people to

build a better life.

Then, UNSECO has focused on technical vocational

education and training, HIV/AIDs prevention education,

and education and planning management. As the chairs of

educational sector working group, UNESCO has played

an important role in facilitating well coordinated and

professional response from the donor community to the

demands of the education development and the request

from government. The main partner in education of

UNESCO is Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport

(MoEYS). UNESCO assists MoEYS for the formulation

and establishment of national education framework and

policy to outreach broader populations. A number of

education policy are formulated with technical support

from UNESCO and other development partners including:

UNICEF in Cambodia has provided de-worming tablet to

95 percent of children in primary school. Moreover,

UNICEF has supported the financial assistance for the

salary of community preschool teacher in order to

improve the preschool to all children. According

government's statistics, the pre-primary school enrollment

rate of Cambodian's five year old in school year 2006-

2007 was 27.7% including state, community, home-based,

and preschool classes. Then, Cambodian government and

UNICEF official maintain that early childhood

development program have proved over and over that

preschool encourages on time enrollment in primary

school and improve academic performance.

Since you focused on the roles and frameworks of MDGs,

UNICEF, UNESCO, you have known that those

frameworks are suitable for improving the education in

Cambodia. However, do these agencies and government

can promise that they will improve or promote education

well as they expect?

According to the statistic from reports, the primary school

projects have been complete successfully. In 2000, there

are around 85% to 86% of children from urban area can

attend school, and for the children in rural area, there are

approximately 82% to 83% go to school, but the children

living in the remote area can attend school only 60% to

63%. From one year to year, the numbers of attending

school from those three areas are increasing gradually. In

fact, in 2009, in remote area the children attend school

about 90.3%. Surprisingly, the urban children which had

the figure higher than others do not increasing

dramatically as the rural area in 2000. Rural area's

children go to school much more than the urban area's

children, is 95% and 92.2%. Nevertheless, projects to

promoting the secondary school is seem failed because

the target of project predicted that about 65.3% in 2009

for the children attending secondary school, but in reality,

there are only 31.9 for students attending school. By the

way, gender disparities in primary school have been

eliminated and regional disparities have also been

eradicated. Then, the proportion of 6-14 years old out of

school is stagnating. Based on the data from CMDGs, the

flow of the line of graph is smooth from 1997 until 2003,

but in 2004 the figures of the data is increasing from

18.7% to 19.81%. Nonetheless, the expected target is only

14.4% in 2008 for the out of school students, so it seems

not go beyond as expectation. Literacy rates of 15 to 24

years old; therefore, in 1998 there is around 82%of

literacy. CMDGs expected that in 2009, there would be

about 92.1% for literacy, but in actual, there is around

87.47% for literacy because the line of the graph was

increasing slowly.

In sum up, education in Cambodia become better than

before. Even so, those agencies need to improve or

promote more because as you known, the education is the

important sector for develop country. Then, in case

education in Cambodia does not good, how could

Cambodia improve or develop country well?

After you have understood about the roles and

frameworks, effect of the agencies, you can say that

though they could not achieve all goals as setting, but

they could improve or promote the education in

Cambodia. As you can see, educational system in

Cambodia has suffered too much during Khmer Rouge

Regime from 1975 to 1979. After that period, the

government has tried to improve it by cooperated and

collaborated with external aid and non-governmental

organization (NGOs). About a half a million Cambodian

children from 6 to 11 years old have no access to school,

then 50% of those who entered grade one dropped out of

school and had to repeat the class. Those problems are

caused by video games, karaoke and the presence of

brothel for the students in city, and for female pupils, they

could not attend school because of many problems.

Due to these problems, the Cambodian government tries

to pay attention on education systems because as

mentioned before, education is very important means to

train and build up human resources for development of

each country and it is also important for development of

child as person. If Cambodian people poor at the

knowledge, how could Cambodia has been developed to

become the strong country as the neighboring countries.

Moreover, the IOs (International organizations) also pay

attention on education sector as well. They try to

encourage and collaborate with Cambodian government

to improving the education systems. As mentioned,

According to the Cambodian constitution, it states that

"the state shall provide free primary and secondary

education to all citizens in public school. Citizens shall

receive education for at least nine years". Then, IOs have

also contributed to improvement as well.

First, UNESCO has improved on teacher education by

providing policy framework and policy choices for

developing teacher professional standards and appropriate

measurement, designing incentives to motivate the

teachers for better teaching and student learning,

deploying qualified teachers to rural and remote areas.

POLICY OF ICT IN EDUCATION

The Ministrys articulation of the policy for ICT in

education focuses on

four main areas

The first area is provide access to ICT for all teachers and

students, especially at secondary level, ensuring that ICT

is used

as an enabler to reduce the digital gap between

Cambodian

schools and other schools in neighbouring countries.

Policy and Strategies on Information and Communication

Technology in Education in Cambodia

The second area emphasizes the role and function of ICT

in education as a teaching and learning tool in different

subjects, and as a subject by itself. Access to information

on the Internet

and increased communication, via email, between schools

and

individuals can play an important role in the professiona

development of educators. In addition to radio and

television as a teaching and learning tool, this policy

stresses the use of the computer for accessing

information, knowledge, skills, and communication. The

third area is to promote education for all regardless of

agegender, ethnicity, disability or location through

distance

education and self-learning, especially for deprived

children,

youth and adults who lack access to basic education,

literacy

and skill training, by integrating ICT with radio,

television printed materials and other media.

The fourth area emphasizes using ICT to increase

productivity, efficiency and effectiveness of education

management. Through

FPH2000

the use of information management systems, ICT will be

extensively used to automate and mechanise work such as

the processing of student and teacher records,

communication between government and schools, lesson

planning, assessment and testing, financial management

and the maintenance of

inventories.

1. BACKGROUND

After almost 30 years of devastating war in Cambodia, the

Royal. Government of Cambodia is trying to develop its

human resources in

order to reconstruct the country and integrate it into the

regional and global community.

The current stage of development

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Irvin What Is Academic WritingДокумент16 страницIrvin What Is Academic WritingMariya MulrooneyОценок пока нет

- Andheri XiiДокумент1 страницаAndheri XiiRishi GargОценок пока нет

- Sample Letter Volunteer Work NgoДокумент1 страницаSample Letter Volunteer Work NgomahiОценок пока нет

- Irvin What Is Academic WritingДокумент16 страницIrvin What Is Academic WritingMariya MulrooneyОценок пока нет

- English - SET - 1Документ8 страницEnglish - SET - 1Rishi GargОценок пока нет

- Grade XIIДокумент26 страницGrade XIIRishi GargОценок пока нет

- Chemistry 1Документ1 страницаChemistry 1Rishi GargОценок пока нет

- Indias Second Green Revolution-LibreДокумент44 страницыIndias Second Green Revolution-LibreRishi GargОценок пока нет

- Optics and Modern Physics PDFДокумент95 страницOptics and Modern Physics PDFRishi GargОценок пока нет

- Chemical Bonding Solution PDFДокумент9 страницChemical Bonding Solution PDFAjay SinghОценок пока нет

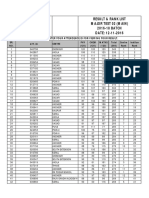

- Ranklist Major Test 2 Main (2016-18) DT 12-11-2016Документ83 страницыRanklist Major Test 2 Main (2016-18) DT 12-11-2016Rishi GargОценок пока нет

- Advanced Functions Ex.1 (B)Документ17 страницAdvanced Functions Ex.1 (B)Rishi GargОценок пока нет

- The Egyptian Civilization 2345678910Документ3 страницыThe Egyptian Civilization 2345678910Rishi GargОценок пока нет

- Shivam FibonacciДокумент4 страницыShivam FibonacciRishi GargОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Exxon MobilДокумент4 страницыExxon MobilcristinaОценок пока нет

- The Historical Timeline of Architecture: IslamicДокумент54 страницыThe Historical Timeline of Architecture: IslamicJean Untalan GugulanОценок пока нет

- 2015 CCG June 15Документ78 страниц2015 CCG June 15SamathHouyОценок пока нет

- 01 PDFДокумент202 страницы01 PDFMouy PhonThornОценок пока нет

- 20140317Документ28 страниц20140317Kristy ElliottОценок пока нет

- Museums in Non-Western Contexts:: Angelina Ong M ST D Writing Requir Ement Spring 2oo7Документ20 страницMuseums in Non-Western Contexts:: Angelina Ong M ST D Writing Requir Ement Spring 2oo7negruperlaОценок пока нет

- Music 8 - Cambodia Ppt2Документ8 страницMusic 8 - Cambodia Ppt2naneth LabradorОценок пока нет

- Format Pengisian 2014 (Uas Tambahan) - 1Документ28 страницFormat Pengisian 2014 (Uas Tambahan) - 1Asari MegaОценок пока нет

- 8.2. 2020, Amita Batra - India's Economic Relevance in The Indo-PacificДокумент15 страниц8.2. 2020, Amita Batra - India's Economic Relevance in The Indo-PacificDina FitrianiОценок пока нет

- Make A Difference With An: Australia Awards ScholarshipДокумент8 страницMake A Difference With An: Australia Awards Scholarshipchim lychhengОценок пока нет

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: HISTORY 9389/43Документ4 страницыCambridge International AS & A Level: HISTORY 9389/43chenjy38Оценок пока нет

- Vietnam WarДокумент19 страницVietnam WarEsih WinangsihОценок пока нет

- SAIS Southeast Asia Studies Newsletter-Spring 2011Документ5 страницSAIS Southeast Asia Studies Newsletter-Spring 2011sacmo_nutzОценок пока нет

- Role of Law and Legal Institutions in Cambodia Economic DevelopmentДокумент410 страницRole of Law and Legal Institutions in Cambodia Economic DevelopmentThach Bunroeun100% (1)

- Country Presentation: CambodiaДокумент11 страницCountry Presentation: CambodiaADBI Events100% (1)

- English Grade 9 Student's BookДокумент275 страницEnglish Grade 9 Student's BookThyry ChanОценок пока нет

- KH 2016 June Investing in Cambodia PDFДокумент40 страницKH 2016 June Investing in Cambodia PDFToan LuongkimОценок пока нет

- Mapeh 8 ModuleДокумент6 страницMapeh 8 Moduletaw real100% (1)

- The Contribution of Social Capital To CBNRM in CambodiaДокумент114 страницThe Contribution of Social Capital To CBNRM in CambodiaChariyaОценок пока нет

- ME2601 English - SAДокумент11 страницME2601 English - SAMeta GoОценок пока нет

- Curriculum VitaeДокумент2 страницыCurriculum VitaeHORT SroeuОценок пока нет

- Tep Rithivit: Joanna Mayhew, Photography Charles FoxДокумент1 страницаTep Rithivit: Joanna Mayhew, Photography Charles FoxJoannaMayhewОценок пока нет

- Monetary Policy in Cambodia: August 29, 2011 2 CommentsДокумент21 страницаMonetary Policy in Cambodia: August 29, 2011 2 CommentsZavieriskОценок пока нет

- Traffic AccidentДокумент19 страницTraffic AccidentAdien D. RockyОценок пока нет

- Desireijimenez CompilationДокумент208 страницDesireijimenez Compilationdi jimОценок пока нет

- Heritage Investment in ThailandДокумент5 страницHeritage Investment in ThailandPacharaporn PhanomvanОценок пока нет

- Alex & Ambrose - BiosДокумент1 страницаAlex & Ambrose - BiosAlex Biniaz-HarrisОценок пока нет

- Breach of Trust in CambodiaДокумент80 страницBreach of Trust in CambodiaSaravorn100% (1)

- The "Missed Chance" For U.S.-Vietnam Relations, 1975-1979Документ28 страницThe "Missed Chance" For U.S.-Vietnam Relations, 1975-1979nvh92Оценок пока нет

- Measuring Khmer Vocabulary Size For Each Grade in Basic EducationДокумент9 страницMeasuring Khmer Vocabulary Size For Each Grade in Basic EducationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет