Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Teachers in Emergencies

Загружено:

api-354511981Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Teachers in Emergencies

Загружено:

api-354511981Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

LANGUAGE ARTS IN A Facilitators Guide

EMERGENCY CONTEXTS

This instructional unit will work to propose a bilingual academic model

for refugee youth that integrates core academic content areas and

comprehensive life skills geared toward the host community.

Jessica A. White, M.Ed.

American University

Emergency Teachers Handbook

The purpose of this handbook is to provide a series of unit shells that are adaptable to a variety

of contexts and languages. It is encouraged that teachers begin with the introductory survey that

will help them to consider the exact needs of their students. Points from the survey will direct

teachers to the appropriate shell with which to begin based on immediate need.

Shells model appropriate progression based on the priorities for varying groups of learners.

Lessons within the shells each contain at least one academic goal based on The International

Baccalaureates programming and assessment models. This is meant to maintain consistent, high

academic standards for the non-traditional academic experience of students in emergencies.

Each unit shell contains guidelines for Primary Years (ages 3-11), Middle Years (ages 12-16),

Secondary Years (academic, ages 16-21) and Career Readiness (vocational, ages 16+).

Table of Contents

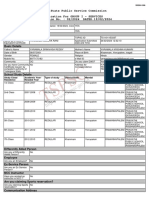

1. Introductory Survey & Scorecard

2. Priority 1: New Language Environment

3. Priority 2: Unfamiliar Laborforce Participation

4. Priority 3: Youth Exploitation

5. Priority 4: Gender and Sexuality Identity Development

6. Priority 5: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

7. Priority 6: Other/Unknown Psychological Distress

1 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

A Note Regarding the Necessity and Use of this Handbook

A number of high-profile organizations across the globe have worked tirelessly to provide

programming to support the continued well-being of people in emergencies. Focus from these

organizations has centered around health and wellness, shelter and medicine (UNHCR 2015). It

bears noting, however, that education provides a means of stability and development for people

of all ages in all situations, particularly for young people in emergencies.

According to UNHCR (2015): The term emergency education is used at inter-agency level to

refer to education in situations where children lack access to their national education systems,

due to man-made crises or natural disasters. Due to this lack of access, it can be assumed that

young learners will require an international standard of education in order to assimilate into any

given education system following the resolution of the crisis that put them in their emergency

situation.

While tireless effort has been made to provide stability programming for young people in

emergencies across the globe, emergency education provisions are visibly lacking. If there is a

system for education in place in a given emergency, it is often inappropriately leveled and results

in the underdevelopment of youth in emergencies around the world (UNHCR 2015). Utilizing

program standards from the internationally renowned and respected International

Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), this handbook instills a high quality of academic expectation

and progress in individuals finding themselves in instructional roles for youth in emergencies. By

converting IBO program standards to flexible and adaptable educational program shells, this

handbook will provide immediate and accessible high quality education program to young people

2 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

in emergency situations, allowing them to settle into a consistent and stable environment that

will also translate well into any national education system following the emergency situation.

This handbook is not limited in scope to a particular audience, nor is it intended for a particular

level of teaching. Per the formulas provided by modern cognition theorists such as Dr. Jean Piaget

(1936), Dr. Lev Vygotsky (1925) and Dr. Benjamin Bloom (1956) coupled with experiential learning

theories coined by Dr. John Dewey (1938), Dr. Howard Gardner (1983) and David Kolb (1984), the

following shells provide essential guidelines for creating experiential, secure learning

environments suitable for students with a variety of cognitive, developmental and psychological

statuses. As a result, there are multiple opportunities to differentiate instruction for a variety of

learning and behavioral needs.

3 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Priority 1: New Language Environment

Just as there are attempts to eradicate discrimination based on color and creed, so people within

this orientation will argue that language prejudice and discrimination need to be eradicated in a

democratic society by establishing language rights (May, 2001; Skutnab-Kangas, 1999b, 2000,

2008; Skutnabb-Kangas & Phillipson, 1994, 2008), (Baker, C. 2011).

According to Colin Baker, language rights concern protection from discrimination, (Baker 2011).

It is critical that students in emergency situations who are placed in a new language environment

are given appropriate academic support to help them (1) continue high-standard academic

progress, (2) develop a working knowledge of the new language for purposes of integration and

basic survival in the event of a long-term displacement and (3) establish a linguistic foundation

that will allow for continuing education.

The following unit shells allow persons in instructional roles to deliver language instruction for

life skills, job readiness and environment adaptation while also activating student knowledge in

order to progress in academic content.

Shell 1: Primary Years Language Arts & Humanities

Shell 2: Primary Years STEM

Shell 3: Middle Years Language Arts & Humanities

Shell 4: Middle Years STEM

Shell 5: Diploma Program Language Arts & Humanities

Shell 6: Diploma Program STEM

Shell 7: Career Readiness Program

4 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Shell 3: Middle Years Language Arts & Humanities

Language Acquisition shells assume that students have had no prior exposure to L2, that

instruction is being delivered by a native L2 speaker with limited- to proficient-level teaching

experience.

Per the IBO standards for Language Acquisition, students should be constantly assessed

according to the following criteria on an achievement scale of 1-8, regardless of content matter:

Criterion A: Comprehending spoken and visual text - Students interpret and construct meaning from

spoken and visual texts to understand how images presented with oral text interplay to convey ideas,

values and attitudes.

Criterion B: Comprehending written and visual text - Students construct meaning and interpret written

and visual text to understand how images presented with written text interplay to convey ideas, values

and attitudes.

Criterion C: Communicating in response to spoken and/or written and/or visual text - Students develop

their communication skills by interacting on a range of topics of personal, local and global interest and

significance, and responding to spoken, written and visual text in the target language.

Criterion D: Using language in spoken and/or written form - Students recognize and use language

suitable to the audience and purpose (for example, home, classroom, formal and informal, social,

academic contexts). Students apply their understanding of linguistic and literary concepts to develop a

variety of structures, strategies and techniques.

(www.ibo.org/programmes)

5 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Data Driven Standards

According to a program evaluation conducted by Ester J. de Jong in 2002, frequent use of achievement

data is critical to the success of a two-way bilingual education program. As such, constant summative and

formative assessment are woven throughout to measure the effectiveness of the program and allow for

instructional adjustment.

Utilizing de Jongs (2002) program evaluation, the following three questions should be constantly

considered by instructors: (1) L1 Component: Are learners developing at appropriate levels of L1

proficiency? (2) L1-L2 Relationship: Does the transfer from L1 literacy skills to L2 literacy skills occur for all

students? What literacy skills transfer? How can we explicitly support this transfer? (3) L2 Component:

Are we providing learners with appropriate and sufficient L2 instruction? (paraphrase de Jong, E. 2002).

Middle Years Language Acquisition & Humanities Essential Shell

In this essential shell, students will utilize current, context-appropriate authentic materials and their

authentic environment to be introduced to key target vocabulary in L2 for purposes of literacy

development. With higher goals of dual-language communication and comprehension per IBO (2016)

standards, given a contemporary newspaper or magazine article the students will draw inferences from

literary cues (e.g. images, repetitive diction) utilizing given sentence structures and new target vocabulary.

Students will demonstrate comprehension of the material through the use of multiple languages by

writing a short, illustrated response article to the given material. Ultimately, students will produce their

own news report on events in their environment using L1, and orally reporting on their findings using

target structures in L2, per the expectations for IBO Standards of Language Acquisition (IBO 2016).

6 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Instructors would be well-advised to select a human interest or other non-political, universally-themed

article when using authentic materials to align with INEE (2010) standards, meaning materials and learning

products should:

Promote equitable distribution of services across identity groups (ethnic, religious, geographic,

gender)

Avoid pockets of exclusion and marginalization

Focus on the reintegration of out-of-school children and youth

Deliver teaching and learning for peace through pedagogy, curriculum and materials that are free

of gender and social prejudices and build competencies for responsible citizenship, conflict

transformation and resilience

Provide psycho-social protection for children

Involve parents, communities, civil society and local leadership

7 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Essential Language Development Delivery Shell

The following steps serve as an essential formula for language development with learners with limited-

to no L2 language proficiency. This structure is also encouraged for learners with higher levels of

proficiency.

Phase 1: Warmer Room to Write / Reflect L1 Familiarization with Artifact

1. Indicate a local (L2) newspaper, flyer or

other authentic, visual-heavy artifact.

2. Model reflection utilizing heavy visual

cues (e.g. pointing to head, eyes;

exaggerated use of pen and paper, etc.)

and limited L2 speech.

3. Again utilizing heavy visual cues, indicate

an opportunity to discuss the visual with a

partner in L1.

4. Bring the class to silence.

Phase 2: L2 Target Vocabulary Introduction

5. Introduce target vocabulary in L2.

6. Utilize other authentic materials to emphasize meaning of L2 target vocabulary.

7. Model physical response to L2

target vocabulary.

8. Elicit choral (group) oral delivery

of L2 target vocabulary utilizing

authentic visual cues.

9. Encourage small group or paired

oral delivery of L2 target

vocabulary utilizing Paired

Activity.

10. Encourage individual oral delivery of L2 target vocabulary.

11. When confidence in L2 target vocabulary is achieved, bring the class to silence.

8 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Phase 3: L2 Target Sentence Structure Introduction

12. Present written form of L2 target vocabulary utilizing available materials and drill.

13. Model oral presentation of desired sentence structure.

14. Elicit choral repetition of target structure.

15. Orally and visually sentence structure to utilize L2 target vocabulary by indicating written forms

of different words.

16. Elicit choral, small group and individual delivery of target structure using different target

vocabulary words.

17. Present written form of structure and demonstrate various sentences using target vocabulary.

18. Encourage paired drilling of target structure.

19. After a given amount of time for mastery, bring the class to silence.

Phase 4: Meaningful Utilization of Target Structure

20. Return to the original authentic visual cue.

21. Elicit target structure from individuals, encouraging physical indication of subjects on visual.

22. Indicate the presence of the target structure in authentic material if applicable.

9 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Authentic Utilization of Target Language Assessment Shell

The following serves as a model for the utilization of an authentic new-language environment

to enhance language acquisition while also meeting cross-curricular IBO standards for

Individuals & Societies (IBO 2016).

IBO standards are best met through portfolio assessment. As such, it is expected that any

materials collected in this section are maintained for later progress assessment. Materials

collected should be evaluated on the following criteria:

Each individuals and societies objective corresponds to one of four equally weighted

assessment criteria. Each criterion has eight possible achievement levels (18), divided into four

bands with unique descriptor that teachers use to make judgments about students work.

Criterion A: Knowing and understanding

Students develop factual and conceptual knowledge about individuals and societies.

Criterion B: Investigating

Students develop systematic research skills and processes associated with disciplines in the

humanities and social sciences. Students develop successful strategies for investigating

independently and in collaboration with others.

Criterion C: Communicating

Students develop skills to organize, document and communicate their learning using a variety

of media and presentation formats.

Criterion D: Thinking critically

Students use critical-thinking skills to develop and apply their understanding of individuals and

societies and the process of investigation.

10 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Phase 1: Modeling and Evaluation of Desired Product

1. Using minimal L2 speech, present students with a sample community evaluation project

(e.g. interview set, newspaper op-ed, photography/sketch collection, etc.)

2. Work backwards to deconstruct the project:

a. Demonstrate the use of finishing paper

b. Demonstrate drafting

c. Demonstrate collecting artifacts

d. Demonstrate critical observation

e. Demonstrate planning

3. Indicate that the students will begin planning

Phase 2: Planning

1. Present students with a structured outline (it is recommended that each student has a

copy, but if copies are not available, students may create their own).

2. Ask: what do you want to know about your community*? (*insert appropriate

vocabulary word here; if not community, could be neighborhood, family, classmates,

food, etc.)

3. Provide visual cues (images or vocabulary words)

4. Model: Elicit questions from students using encouragement from the images and

vocabulary words and visibly record them. Then, break questions into bullet-able points

and demonstrate

5. Model, using outline: I want to know about 3-5 points.

6. Encourage students to build their own outline.

7. Encourage sharing and/or discussion of outlines.

11 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Phase 3: Critical Observation

It is highly recommended that observation take place in such a way that the instructor may

escort and assist students, but in some cases (e.g. learning about family) this may not be

necessary.

1. Model: indicate and orally repeat targets from outline

2. Model: pretend to observe your environment and, using exaggerated visual cues,

demonstrate note-taking about your surroundings; using limited L2 speech, think out

loud.

3. Encourage students to participate, eliciting their observations

4. Encourage students to also record their observations in either language

5. Travel: what else can we see? Venture into the community to observe targets.

6. Return: Encourage students to discuss, in either language, what they observed.

7. Assess: Using learned targets, encourage students to share their findings in L2.

Phase 4: Collection of Artifacts

1. Model: using model outline, create a list of questions to be answered

2. Model: if materials are available to do so, dress a volunteer student up like a stranger

and proceed to ask model questions about given topic. Elicit other questions from class.

3. Encourage half the class to dress as strangers and practice asking and answering

model questions.

4. Indicate students outlines and encourage them to write questions.

5. Travel: Venture into the community and encourage the collection of artifacts

6. Return: Encourage students to discuss, in either language, what they observed.

7. Assess: Using learned targets, encourage students to share their findings in L2. Passively

correct language (do not interfere with communication) as needed.

12 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Phase 5: Drafting

1. Model: Using observation notes and outline, demonstrate the creation of complete

sentences. Leave spaces for photographs/sketches if appropriate to do so.

2. Encourage students to return to their own notes and create sentences.

3. Assess: elicit sample sentences from students in L2, actively correcting language as

needed.

4. Model: order sentences in logical progression

5. Encourage students to continue writing sentences from their observations and to place

them in logical order.

Phase 6: Finishing

In some environments, actual finishing materials may not be available. Clean paper will suffice

in most instances.

1. Model: transfer rough sentences and/or images from draft to finishing material

2. Encourage students to do the same with their own materials.

13 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

References

Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. Bristol, UK: Multilingual

Matters.

INEE. (2015) Education in Emergencies. Retrieved December 04, 2016, from

http://www.ineesite.org/en/education-in-emergencies

UNESCO. (2016). Education in Emergencies. Retrieved December 04, 2016, from

http://en.unesco.org/themes/education-emergencies

UNICEF (2006) Education in Emergencies: A Resource Toolkit Retrieved December 04, 2016,

from http://www.unicef.org/2frosa/2fRosa-Education_in_Emergencies_ToolKit.pdf

Jong, E. J. (2002). Effective Bilingual Education: From Theory to Academic Achievement in a

Two-Way Bilingual Program. Bilingual Research Journal, 26(1), 65-84.

doi:10.1080/15235882.2002.10668699

IBO. (2015). Middle years | 11 to 16 | International Baccalaureate. Retrieved December 1,

2016, from http://www.ibo.org/programmes/middle-years-programme/

14 | J. White ELA in Emergencies

Вам также может понравиться

- EDU 603 Final Project OLGA ARBULU FinalДокумент55 страницEDU 603 Final Project OLGA ARBULU FinalOlga ArbuluОценок пока нет

- EDU 603 Final Project OLGA ARBULU FinalДокумент55 страницEDU 603 Final Project OLGA ARBULU FinalOlga ArbuluОценок пока нет

- Ej1085389 PDFДокумент16 страницEj1085389 PDFSaya AamОценок пока нет

- Wal Qui 2006Документ23 страницыWal Qui 2006Christian XavierОценок пока нет

- Equity For English LearnersДокумент22 страницыEquity For English LearnerskinyzoОценок пока нет

- Stanford ELD Fundamentals 3 - 16 - 22Документ5 страницStanford ELD Fundamentals 3 - 16 - 22ChrisОценок пока нет

- Multilingual and Multicultural EducationДокумент43 страницыMultilingual and Multicultural EducationVeo Paolo TidalgoОценок пока нет

- Tugas BilingualДокумент3 страницыTugas BilingualTria AwandhaОценок пока нет

- Bilingual Immersion PDFДокумент19 страницBilingual Immersion PDFJack ChanОценок пока нет

- EFL Journal November 2018 Lexical Voids Percara BayonaДокумент49 страницEFL Journal November 2018 Lexical Voids Percara BayonaSMBОценок пока нет

- Literature Review-PBL and Blended LearningДокумент12 страницLiterature Review-PBL and Blended LearningBret GosselinОценок пока нет

- Bilingualism For AllДокумент25 страницBilingualism For AllTipsuda CmkОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ6 страницChapter 1ashley Mae LacuartaОценок пока нет

- Edu603 Dejesus FinalДокумент35 страницEdu603 Dejesus Finalapi-736693318Оценок пока нет

- Cross-Curricular Connections: Video Production in A K-8 Teacher Preparation ProgramДокумент14 страницCross-Curricular Connections: Video Production in A K-8 Teacher Preparation ProgramAlberto ZapataОценок пока нет

- The Culturally Diverse ClassroomДокумент11 страницThe Culturally Diverse ClassroomDanusa Jeremin100% (1)

- Unit Overview - Shogun JapanДокумент16 страницUnit Overview - Shogun Japanapi-233668463Оценок пока нет

- Communication Disorders QuarterlyДокумент9 страницCommunication Disorders QuarterlyMã-ngơ Cực Yêu CừubéoОценок пока нет

- Celin Brief Designing and Implementing Chinese Language ProgramsДокумент11 страницCelin Brief Designing and Implementing Chinese Language ProgramsangelaОценок пока нет

- Research Powerpoint in Spelling DifficultiesДокумент18 страницResearch Powerpoint in Spelling DifficultiesMfcf Lacgno OdibasОценок пока нет

- MulticulturismДокумент8 страницMulticulturismRose DonquilloОценок пока нет

- Siop SlideshowДокумент24 страницыSiop Slideshowapi-547677969Оценок пока нет

- Research Paper Bilingual EducationДокумент6 страницResearch Paper Bilingual Educationegya6qzc100% (1)

- Bilingualism Dissertation TopicsДокумент7 страницBilingualism Dissertation TopicsPaperWritingHelpOnlineReno100% (1)

- Using Home Language as a Resource in the Classroom: A Guide for Teachers of English LearnersОт EverandUsing Home Language as a Resource in the Classroom: A Guide for Teachers of English LearnersОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal CheckingДокумент5 страницResearch Proposal Checkingjeremymaiquez0920Оценок пока нет

- Lit ReviewДокумент10 страницLit Reviewapi-340001912Оценок пока нет

- Research Paper Focusing On A Fundamental and Re-Occurring Theme in Bilingual Special EducationДокумент9 страницResearch Paper Focusing On A Fundamental and Re-Occurring Theme in Bilingual Special EducationKyle Andre IbonesОценок пока нет

- Kyoto UniversityДокумент8 страницKyoto UniversityjohnОценок пока нет

- Bilingual DissertationДокумент6 страницBilingual DissertationWriteMyEnglishPaperUK100% (1)

- Enhancing Learning of Children From Diverse Language BackgroundsДокумент91 страницаEnhancing Learning of Children From Diverse Language BackgroundsAdeyinka PekunОценок пока нет

- LPPMS 1Документ24 страницыLPPMS 1KAREN SALVE MAUTEОценок пока нет

- Review of Instructional Materials:: Identities: English Is Part of Who I AmДокумент4 страницыReview of Instructional Materials:: Identities: English Is Part of Who I AmBersain Chacha CotoОценок пока нет

- Thesis Bilingual EducationДокумент8 страницThesis Bilingual EducationDoMyPaperForMeSingapore100% (2)

- Assignment 2 EssayДокумент12 страницAssignment 2 Essayapi-518728602Оценок пока нет

- Final ProjectДокумент26 страницFinal ProjectLIFE WITH BRIANNAОценок пока нет

- Article 2Документ12 страницArticle 2AgusОценок пока нет

- Midterm Module 5Документ10 страницMidterm Module 5Janet A. LopezОценок пока нет

- Authentic Texts in Teaching EnglishДокумент6 страницAuthentic Texts in Teaching EnglishSerdar DoğanОценок пока нет

- Final Paper Learning Theories 29 10 2013 Verison 1 1Документ10 страницFinal Paper Learning Theories 29 10 2013 Verison 1 1api-257576999Оценок пока нет

- Purpose of Curriculum ImprovementДокумент17 страницPurpose of Curriculum ImprovementJennifer DizonОценок пока нет

- Paper 3Документ21 страницаPaper 3doductrung20022211Оценок пока нет

- Language Curriulum - Module - 3Документ12 страницLanguage Curriulum - Module - 3RICHARD ALFEO ORIGINALОценок пока нет

- Literature ReviewДокумент18 страницLiterature Reviewapi-547018120Оценок пока нет

- 2 PBДокумент15 страниц2 PBDimaz Ananda RizkyОценок пока нет

- Cordy J s206946 Ela201 Assignment2Документ18 страницCordy J s206946 Ela201 Assignment2api-256832695Оценок пока нет

- Social Studies ImmigrationДокумент22 страницыSocial Studies ImmigrationMariam BazerbachiОценок пока нет

- Promoting Success of Multilevel Esl Classes PDFДокумент5 страницPromoting Success of Multilevel Esl Classes PDFElizabethBorgesОценок пока нет

- Dewaele 2019Документ16 страницDewaele 2019Omar KriâaОценок пока нет

- Whatis Immersion LearningДокумент27 страницWhatis Immersion LearningOppo A7Оценок пока нет

- Action Research in TVE EIMДокумент19 страницAction Research in TVE EIMLand NozОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal Group 4Документ6 страницResearch Proposal Group 4jeremymaiquez0920Оценок пока нет

- Dissertation Bilingual EducationДокумент8 страницDissertation Bilingual EducationAcademicPaperWritingServicesCanada100% (1)

- CombatДокумент12 страницCombatapi-240606759Оценок пока нет

- Updatedct898 Jellison Caep1Документ7 страницUpdatedct898 Jellison Caep1api-367504817Оценок пока нет

- P21Map DAversion 11.09.10Документ12 страницP21Map DAversion 11.09.10MmeTheisenОценок пока нет

- The Essentials: Dual Language Learners in Diverse Environments in Preschool and KindergartenОт EverandThe Essentials: Dual Language Learners in Diverse Environments in Preschool and KindergartenОценок пока нет

- Educating Through Pandemic: Traditional Classroom Vs Virtual Space - the Education RealmОт EverandEducating Through Pandemic: Traditional Classroom Vs Virtual Space - the Education RealmОценок пока нет

- Reading Comprehension: Practice Test 2Документ28 страницReading Comprehension: Practice Test 2api-354511981Оценок пока нет

- Suite360 DemoДокумент17 страницSuite360 Demoapi-354511981Оценок пока нет

- Flipped Classroom Workshop - Facilitators GuideДокумент17 страницFlipped Classroom Workshop - Facilitators Guideapi-354511981Оценок пока нет

- Huck Finn SatireДокумент2 страницыHuck Finn Satireapi-354511981Оценок пока нет

- A Farewell To ArmsДокумент7 страницA Farewell To Armsapi-354511981Оценок пока нет

- Item Analysis: Item Difficulty/Difficulty IndexДокумент3 страницыItem Analysis: Item Difficulty/Difficulty IndexAngelica Flora100% (2)

- StudySync - Think - Life After High SchoolДокумент2 страницыStudySync - Think - Life After High Schoolprogirl 321Оценок пока нет

- Nurses 2019 Marks 28062019Документ1 285 страницNurses 2019 Marks 28062019rajaguru20003Оценок пока нет

- BKD MinutesДокумент2 страницыBKD MinutesKimelouMortelAmatiagaОценок пока нет

- Catch Up Friday Grade 9 10Документ7 страницCatch Up Friday Grade 9 10niwtrA zedneMОценок пока нет

- The Education System in IranДокумент2 страницыThe Education System in Iranafshin sajediОценок пока нет

- Class-Programs-2022 PEGASUSДокумент21 страницаClass-Programs-2022 PEGASUSJENEVIE SALIOTОценок пока нет

- Ces Gad Proposal 2020-2021Документ7 страницCes Gad Proposal 2020-2021Anah Chel IcainОценок пока нет

- Genuine Temporary Entrant StatementДокумент2 страницыGenuine Temporary Entrant StatementmobydickОценок пока нет

- Computer Skills: MS Office Application (MS Word, MS Excel, MS Power Point, MS Access), E-Mail &Документ2 страницыComputer Skills: MS Office Application (MS Word, MS Excel, MS Power Point, MS Access), E-Mail &NADIM MAHAMUD RABBIОценок пока нет

- Assessment JC and LC 2022 ArrangementsДокумент100 страницAssessment JC and LC 2022 ArrangementsJimmy EvansОценок пока нет

- Anyon - Social Class and School KnowledgeДокумент31 страницаAnyon - Social Class and School KnowledgeCelia EydelandОценок пока нет

- Accomplishment Report and WinningsДокумент6 страницAccomplishment Report and WinningsReynaldo MilarОценок пока нет

- Admission Admtsston: Murmu &Документ13 страницAdmission Admtsston: Murmu &JyotirmayeeОценок пока нет

- Classroom Level Language Mapping Validation Form KinderДокумент1 страницаClassroom Level Language Mapping Validation Form KinderShielo RestificarОценок пока нет

- Legal Basis On Special EducationДокумент15 страницLegal Basis On Special EducationHearthy AnneОценок пока нет

- Kasturi Ram College of Higher Education, Narela, Delhi-110040Документ2 страницыKasturi Ram College of Higher Education, Narela, Delhi-110040Nipun KhatriОценок пока нет

- ,ffi/ '.@ I 9 (9ro6: OnsloruДокумент2 страницы,ffi/ '.@ I 9 (9ro6: OnsloruTechnetОценок пока нет

- Free Tuition Fee Application Form: University of Rizal SystemДокумент2 страницыFree Tuition Fee Application Form: University of Rizal SystemCes ReyesОценок пока нет

- Wainganga College of Engineering & Management: "Study of Tax Saving Instruments For Individual"Документ6 страницWainganga College of Engineering & Management: "Study of Tax Saving Instruments For Individual"anup1323Оценок пока нет

- (Application No. 2021700527) Has Been Provisionally Selected For Admission ToДокумент1 страница(Application No. 2021700527) Has Been Provisionally Selected For Admission ToSanjay Sanju YadavОценок пока нет

- PDF - Osp How To Make The Most Your Practice TimeДокумент1 страницаPDF - Osp How To Make The Most Your Practice TimeSabrina Arfanindia DeviОценок пока нет

- State Common Entrance Test Cell: 3119 St. Francis Institute of Management & Research, MumbaiДокумент5 страницState Common Entrance Test Cell: 3119 St. Francis Institute of Management & Research, MumbaiClovis MachadoОценок пока нет

- in AssessmentДокумент15 страницin AssessmentJulie Ann ParicaОценок пока нет

- Hansraj College, Delhi: Notice: First Cut-Off List (Online Admissions: 2021-22)Документ1 страницаHansraj College, Delhi: Notice: First Cut-Off List (Online Admissions: 2021-22)PINKI KUMARIОценок пока нет

- DVUSD 2011-2012 District CalendarДокумент1 страницаDVUSD 2011-2012 District CalendarStetson Hills PtsaОценок пока нет

- USW1 EDUC 3056 Elementary Education Lesson Plan TemplateДокумент6 страницUSW1 EDUC 3056 Elementary Education Lesson Plan TemplateRoopa NatarajОценок пока нет

- UNIT 10 LIFELONG LEARNING Nguyen Viet HoangДокумент7 страницUNIT 10 LIFELONG LEARNING Nguyen Viet Hoanghoàng nguyễnОценок пока нет

- Telangana State Public Service Commission Edit Application For GROUP I - SERVICES Notification No.: 02/2024 DATED.19/02/2024Документ3 страницыTelangana State Public Service Commission Edit Application For GROUP I - SERVICES Notification No.: 02/2024 DATED.19/02/2024Anusha Rani YaramalaОценок пока нет

- Electrical Installation-Cba 2020Документ267 страницElectrical Installation-Cba 2020nassoro waziriОценок пока нет