Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Perioperative Stroke: Review Article

Загружено:

kucingkucingОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Perioperative Stroke: Review Article

Загружено:

kucingkucingАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

review article

Current Concepts

Perioperative Stroke

Magdy Selim, M.D., Ph.D.

S

From the Department of Neurology, Divi- troke is one of the most feared complications of surgery. to pro-

sion of Cerebrovascular Diseases, Beth vide adequate preventive and therapeutic measures, physicians need to be

Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Selim at knowledgeable about the risk factors for stroke during the perioperative peri-

the Department of Neurology, Division od. In this article, I review the pathophysiology of perioperative stroke and pro-

of Cerebrovascular Diseases, Beth Israel vide recommendations for the stratification of risk and the management of risk

Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline

Ave., Palmer 127, Boston, MA 02215, or at factors.

mselim@bidmc.harvard.edu.

N Engl J Med 2007;356:706-13.

Incidence

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

The incidence of perioperative stroke depends on the type and complexity of the

surgical procedure. The risk of stroke after general, noncardiac procedures is very

low. Cardiac and vascular surgeries in particular, combined cardiac procedures

are associated with higher risks1-7 (Table 1). The timing of surgery is also impor-

tant. More strokes occur after urgent surgery than after elective surgery.1

Despite advances in surgical techniques and improvements in perioperative

care, the incidence of perioperative strokes has not decreased, reflecting the aging

of the population and the increased number of elderly patients with coexisting con-

ditions who undergo surgery. Perioperative strokes result in a prolonged hospital

stay and increased rates of disability, discharge to long-term care facilities, and

death after surgery.7

Pathophysiology

Radiologic and postmortem studies indicate that perioperative strokes are pre-

dominantly ischemic and embolic.8-10 In a study of 388 patients with stroke after

coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG), hemorrhage was reported in only 1% of

patients; 62% had embolic infarcts11 (Fig. 1). The timing of embolic strokes after

surgery has a bimodal distribution. Approximately 45% of perioperative strokes are

identified within the first day after surgery.1,11 The remaining 55% occur after un-

eventful recovery from anesthesia, from the second postoperative day onward.1,11

Early embolism results especially from manipulations of the heart and aorta or

release of particulate matter from the cardiopulmonary-bypass pump.1,7,13 Delayed

embolism is often attributed to postoperative atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarc-

tion resulting from an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand,

and coagulopathy.13 Surgical trauma and associated tissue injury result in hyperco-

agulability. Several studies have shown activation of the hemostatic system and

reduced fibrinolysis after surgery, as evidenced by decreased tissue plasminogen

activator (t-PA) and increased plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 activity and

increased levels of fibrinogen-degradation products, thrombinantithrombin com-

plex, thrombus precursor protein, and d-dimer immediately after surgery and up to

706 n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

14 to 21 days postoperatively.14-16 General anes-

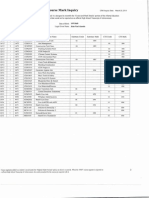

Table 1. Incidence of Stroke after Various Surgical Procedures.

thesia, dehydration, bed rest, stasis in the post-

operative period, and perioperative withholding Procedure Risk of Stroke (%)

of antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents can ag- General surgery2 0.080.7

gravate surgery-induced hypercoagulability and Peripheral vascular surgery 3 0.83.0

increase the risk of perioperative thrombogenic Resection of head and neck tumors4 4.8

events, including stroke. 5

Carotid endarterectomy 5.56.1

There is increasing recognition that short-

1,7

and long-term cognitive changes, manifested as Isolated CABG 1.43.8

1,7

short-term memory loss, executive dysfunction, Combined CABG and valve surgery 7.4

and psychomotor slowing, occur after CABG.7 The Isolated valve surgery1 4.88.8

multifactorial causes of these changes include Double- or triple-valve surgery1 9.7

ischemic injury from microembolization, surgi- Aortic repair7 8.7

cal trauma, preexisting vascular changes, and

temperature during surgery.

Contrary to common belief, most strokes in

patients undergoing cardiac surgery, including

Multiple

those with carotid stenosis, are not related to hy- 10%

poperfusion. Deliberate hypotension induced by Embolic

62%

anesthesia does not seem to adversely affect ce-

rebral perfusion, nor does it considerably increase

the risk of perioperative stroke due to hypoper-

fusion in patients with carotid stenosis.6,11,15 Most Unclassified

14%

perioperative strokes in such patients are embolic

and are either contralateral to the affected carotid

artery or bilateral (Fig. 2), so they cannot be at-

tributed to carotid stenosis alone.6 In one study, Lacunar 3%

only 9% of strokes after CABG were in water- Thrombotic 1%

shed (hypoperfusion) areas.11 As expected, most Hemorrhagic 1%

were identified within the first day after surgery.

Hypoperfusion

Delayed hypoperfusion strokes, when they occur, 9%

are often precipitated by postoperative dehydra-

tion or blood loss. Other, less common causes of Figure 1. Mechanisms of Perioperative Stroke.

perioperative stroke include air, fat, or paradoxical Data are from Likosky et al.12

embolism and arterial dissection resulting from

neck manipulations during induction of anesthe- ICM

AUTHOR: Selim RETAKE 1st

sia and neck surgery (Table 2). observationalREG studyF of 33,062

FIGURE: 1 of consecutive

2 patients 2nd

17 3rd

undergoing CABG. CASE Table 4 summarizes the ma- Revised

Risk Stratification jor elements of EMailthisARTIST:

predictive model.

Line 18 4-C SIZE

ts H/T H/T

Several patient- and procedure-related factors are Enon 22p3

Combo

associated with an increased risk of perioperative Risk Modification AUTHOR, PLEASE NOTE:

stroke (Table 3).2,4,6,8,13,15,16 Evaluating the risk Physicians can implement

Figure has beendiagnostic,

redrawn and typetherapeu-

has been reset.

Please check carefully.

benefit ratio for each patient before surgery is es- tic, and procedural measures to modify the peri-

sential to optimize care. There are several models operative risk JOB:in35607

order to prevent stroke and ISSUE: mini- 02-15-06

for stratifying the risk of perioperative stroke.7,17 mize morbidity. A history of stroke or transient

Investigators from the Northern New England Car- ischemic attack is a strong predictor of periop-

diovascular Disease Study Group used bootstrap- erative stroke.2,4,68,12,13,17 Therefore, physicians

ping techniques to develop and validate a model must inquire specifically about such a history and

predicting the risk of stroke after CABG, accord- fully investigate and treat the cause of a stroke or

ing to weights assigned to seven preoperative transient ischemic attack that has occurred with-

variables. These variables were identified in an in the previous 6 months, especially if a previous

n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007 707

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

carotid Doppler ultrasound; patients with carotid

stenosis that has been symptomatic within the

previous 6 months benefit from carotid revascu-

larization before undergoing cardiac or major

vascular surgery.20 In patients with both cardiac

and carotid disease who are undergoing urgent

cardiac surgery a population in which the risks

of complications and death from cardiac causes

exceed the risk of stroke a reversed-stage ap-

proach (carotid revascularization after CABG) or

a combined approach (simultaneous carotid re-

vascularization and CABG) may be undertaken.

However, the combined approach may be associ-

ated with higher morbidity.21 The safety of ca-

rotid endarterectomy as compared with carotid

stenting is under investigation. Preliminary evi-

dence suggests that carotid stenting is probably

more suitable for patients with concomitant symp-

Figure 2. MRI Scan Showing Embolic Infarcts tomatic carotid and coronary artery disease in

in a 74-Year-Old Man with Stroke after CABG. whom preoperative carotid revascularization is

The patient had left extracranial internal carotid steno- being considered.22

sis (60 to 69% on Doppler ultrasonography), type 2 di- The effect of asymptomatic carotid stenosis,

abetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. The

especially when it is unilateral, on the risk of peri-

diffusion-weighted MRI scan shows small, bright-signal

abnormalities in the right hemisphere, which are consis- operative stroke is often overstated. A review of

tent with embolic infarcts, with no evidence of infarcts the literature from 1970 to 2000 showed an over-

ipsilateral to the carotid lesion. all risk of stroke of 2% after CABG; the risk in-

creased to 3% among patients with asymptom-

atic unilateral carotid stenosis of 50 to 99%, 5%

evaluation was not done or was incomplete or if among those with bilateral stenoses of 50 to 99%,

the patients neurologic status worsened after the and 7% among those with carotid occlusion.6 Sixty

event. Brain vascular reserve is often tenuous in percent of perioperative infarcts in patients with

the days after a stroke, so it is important to allow carotid stenosis were attributed to causes other

sufficient time after a stroke for the patients he- than carotid disease.6

modynamic and neurologic status to stabilize be- The discovery of asymptomatic carotid steno-

fore an elective surgical procedure is performed. sis often begins with the detection of a cervical

The risk of perioperative stroke is high among bruit during preoperative evaluation. Since the

patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis.6,19 presence of an asymptomatic bruit, in itself, is not

Such patients should be evaluated by means of correlated with the risk of perioperative stroke or

the severity of the underlying carotid stenosis,23

Table 2. Uncommon Causes of Perioperative Stroke. routine carotid evaluation by means of Doppler

ultrasound is unnecessary in these circumstanc-

Air embolism after endoscopic procedures, intravascular interventions,

and cardiopulmonary bypass es. However, carotid ultrasound may be warranted

Fat embolism after orthopedic procedures in patients with bruits who have a recent history

of transient ischemic attacklike symptoms. Fur-

Paradoxical embolism from postoperative deep-vein thrombosis in patients

with patent foramen ovale thermore, few data provide support for the rou-

Extracranial carotid- or vertebral-artery dissections resulting from neck manip-

tine use of prophylactic revascularization before

ulations and hyperextension of the neck during induction of anesthesia, major cardiovascular surgery in patients with

neck surgery, or dental procedures asymptomatic carotid stenosis.24

Dislodgment of arterial atherosclerotic plaques resulting from manipulations Revascularization before surgery is generally

of extracranial internal carotid or vertebral arteries during neck surgeries unwarranted because it exposes patients to the

Spinal cord infarct after surgery to repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm risks of perioperative stroke and myocardial in-

farction twice without significantly reducing the

708 n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

Table 3. Risk Factors for Perioperative Stroke.

Preoperative (patient-related) risk factors

Advanced age (>70 yr)*

Female sex

History of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency (creatinine, >2 mg/dl [177 mol/liter]), smoking, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, cardiac disease (coronary artery disease, arrhythmias,

heart failure), and systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction, <40%)

History of stroke or transient ischemic attack

Carotid stenosis (especially if symptomatic)

Atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta (in patients undergoing cardiac surgery)

Abrupt discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy before surgery

Intraoperative (procedure-related) risk factors

Type and nature of the surgical procedure

Type of anesthesia (general or local)

Duration of surgery and, in cardiac procedures, duration of cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross-clamp time

Manipulations of proximal aortic atherosclerotic lesions

Arrhythmias, hyperglycemia, hypotension, or hypertension

Postoperative risk factors

Heart failure, low ejection fraction, myocardial infarction, or arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation)

Dehydration and blood loss

Hyperglycemia

* Age itself does not predict the risk of stroke, and the 70-year cutoff is arbitrary. However, advanced age is a marker

of decreased cerebrovascular reserve and multiple coexisting conditions.

The effect of systolic dysfunction on the risk of perioperative stroke is particularly pronounced among patients under-

going left-main-stem revascularization and those with atrial fibrillation.

risk of stroke.6,19,20 However, some patients with and cost-effectiveness of hemodynamic testing

hemodynamically significant, high-grade, asymp- before surgery are debatable, and further devel-

tomatic carotid stenosis in particular those opment and validation of these tests are required

with bilateral stenoses may benefit from ca- before their routine preoperative use in patients

rotid revascularization before elective surgery. with carotid stenosis can be advocated.

Therefore, the extent of the preoperative evalua- Aortic atherosclerosis is an independent pre-

tion of patients with asymptomatic carotid dis- dictor of the risk of perioperative stroke, particu-

ease should be individualized. At a minimum, larly among patients undergoing cardiac surgery

the evaluation should include a detailed neuro- and revascularization of the left main-stem ar-

logic examination, a history taking designed to tery.1,13 Identifying the extent and location of

elicit unreported symptoms of transient ischemic aortic atherosclerosis before or at the time of sur-

attack, and brain computed tomographic (CT) or gery by means of transesophageal echocardiog-

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies to rule raphy or intraoperative epiaortic ultrasound is

out silent ipsilateral infarcts. Additional tests important to modify the surgical technique and

such as transcranial Doppler ultrasonography change the site of aortic cannulation or clamp-

and intracranial CT or magnetic resonance angi- ing to avoid calcified plaques. The use of echo-

ography to determine the microembolic signal cardiography-guided aortic cannulation27 and in-

load, intracranial blood flow, and hemodynamic traaortic filtration28 during CABG can reduce the

significance of the carotid stenosis25,26 may pro- risk of perioperative stroke.

vide incremental information to identify patients Systolic dysfunction increases the risk of peri-

who could benefit from carotid revascularization operative stroke, particularly among patients with

before surgery. However, the clinical usefulness atrial fibrillation.13 Preoperative echocardiogra-

n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007 709

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

volume increase atrial ectopic activity, which con-

Table 4. Model for Predicting the Risk of Stroke among Patients Undergoing

CABG.* fers a predisposition to arrhythmia 29 (Table 5).

It is therefore important to monitor patients for

Risk Factor Weighted Score arrhythmias for a minimum of 3 days after cardiac

Advanced age procedures as well as to correct electrolytes and

6069 yr 1.5 fluid volume during the postoperative period.

7079 yr 2.5 The incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation

and stroke may be reduced by the prophylactic

80 yr 3.0

administration of amiodarone and beta-block-

Nonelective surgery ers, beginning 5 days before cardiac surgery.30

Immediate 1.5 Patients with preexisting atrial fibrillation may

Within hours 3.5 be receiving antiarrhythmic or rate-controlling

Female sex 1.5 agents, which should be continued throughout

the perioperative period, with the use of intrave-

Ejection fraction <40% 1.5

nous formulations if needed. No controlled tri-

Vascular disease 1.5 als have specifically addressed the use of anti-

Diabetes mellitus 1.5 coagulation therapy for new-onset, postoperative

Creatinine >2 mg/dl (177 mol/liter), or dialysis 2.0 atrial fibrillation, which often resolves sponta-

Total Score Risk of Stroke (%) neously after 4 to 6 weeks. The American College

of Chest Physicians recommends the consider-

01 0.4

ation of heparin therapy particularly for high-risk

2 0.6

patients, such as those with a history of stroke

3 0.9 or transient ischemic attack, in whom atrial fibril-

4 1.3 lation develops after surgery and the continua-

5 1.4 tion of anticoagulation therapy for 30 days after

6 2.0

the return of a normal sinus rhythm.31

The discontinuation of warfarin or antiplate-

7 2.7

let agents in anticipation of surgery exposes

8 3.4 patients to an increased risk of perioperative

9 4.2 stroke.32,33 The risk is particularly high among

10 5.9 patients with coronary artery disease.32 A review

11 7.6

of the perioperative outcomes of patients requir-

ing long-term warfarin therapy showed that rates

12 >10.0

of thromboembolic events varied according to

* Adapted from Charlesworth et al.18 The risk factors have an additive effect, the management strategy; the rate was 0.6% for

producing an aggregate estimate of the risk of perioperative stroke among pa- discontinuation of warfarin without the admin-

tients undergoing CABG. istration of intravenous heparin and 0% for dis-

This includes a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, vascular surgery,

carotid stenosis or bruit, or leg amputation or vascular bypass surgery. continuation of warfarin with intravenous hep-

arin used as bridge therapy.34 The rate of major

bleeding that occurred while the patient was re-

phy to assess the ejection fraction and to look for ceiving a therapeutic dose of warfarin was 0.2%

intracardiac emboli and aortic atherosclerosis may for dental procedures and 0% for arthrocentesis,

help to stratify the risk of stroke and modify the cataract surgery, and upper endoscopy or colo-

treatment strategy for patients with heart fail- noscopy with or without biopsy.

ure, atrial fibrillation, or suspected valvular dis- A study of patients at high risk for thrombo-

ease and those undergoing revascularization of embolism who were undergoing knee or hip re-

the left main stem. placement surgery showed that continued use of

Atrial fibrillation occurs in 30 to 50% of pa- moderate-dose warfarin therapy (international

tients after cardiac surgery, with a peak incidence normalized ratio, 1.8 to 2.1) during the periop-

between the second and fourth postoperative erative period was safe and effective in prevent-

days, and it is a major cause of many periopera- ing embolic events.35 These studies suggest that

tive strokes.1,8,9,13,17,18,29 Postoperative electro- most patients can undergo dental procedures, ar-

lyte imbalance and shifts in the intravascular throcentesis, cataract surgery, diagnostic endos-

710 n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

copy, and even orthopedic surgery without inter-

Table 5. Predictors of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation.

rupting their antiplatelet or oral anticoagulation

regimen. When oral anticoagulation must be with- Advanced age

held for other invasive procedures, the time dur- History of preoperative atrial fibrillation or supraventricular arrhythmias

ing which anticoagulation is being withheld

Preoperative heart failure or low ejection fraction

should be minimized. Bridge therapy with hepa-

rin after discontinuation of warfarin and early Perioperative withdrawal of angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitors or

beta-blockers

postoperative resumption of anticoagulation is

recommended, especially in patients at high risk Previous inferior-wall myocardial infarction

for thromboembolism, such as those with a his- Combined CABG and valve-replacement surgery

tory of systemic embolism or atrial fibrillation

High postoperative magnesium levels

and those with mechanical valves.36

Surgeons should attempt to minimize the

duration of surgery whenever possible. Lengthy view showed a trend toward a reduction in the rate

operations are associated with higher risks for of perioperative stroke when the patients core

perioperative illness and stroke. The choice of body temperature during cardiopulmonary bypass

the surgical technique according to the patients was 31.4 to 33.1C, as compared with a tempera-

risk profile is also important. Among patients ture of more than 33.2C.44 However, this benefit

with a low ejection fraction, the risk of stroke is offset by a higher rate of death among patients

may be lower with coronary angioplasty than with with lower core temperatures. On balance, it is

CABG,37 and off-pump as compared with on-pump advisable to maintain mild hypothermia (approxi-

cardiopulmonary bypass may be associated with mately 34C) during cardiopulmonary bypass and

a lower risk of stroke among patients with severe to avoid rapid rewarming and hyperthermia after

atheromatous aortic disease.38 A no-touch tech- surgery in order to minimize the risk of cognitive

nique, avoiding manipulations of the ascending impairment after CABG.44

aorta, is advised whenever feasible in patients with Hyperglycemia, intraoperatively and postop-

aortic arch disease.39 eratively, is associated with increased rates of

The type of anesthesia and the anesthetic agent atrial fibrillation, stroke, and death.45 Intensive

are additional considerations. Regional anesthe- monitoring and control of the patients glucose

sia is less likely than general anesthesia to result level during the perioperative period is important.

in perioperative complications.40 Some data sug- The administration of insulin and potassium dur-

gest that isoflurane and thiopentone may provide ing and after surgery to keep blood glucose levels

neuroprotection.41 below 140 mg per deciliter (7.8 mmol per liter) is

The optimal level of blood pressure during associated with improved outcomes.46

surgery is debatable.12,17 In one study, the inci- The prevention and treatment of inflamma-

dence of cardiac and neurologic complications, tion and infections during the preoperative and

including stroke, was significantly lower when postoperative periods are always indicated. A high

the mean systemic arterial pressure was 80 to 100 white-cell count correlates with an increased inci-

mm Hg during CABG, as compared with 50 to 60 dence of stroke, poor outcome, and the develop-

mm Hg, suggesting that a higher mean systemic ment of postoperative atrial fibrillation.47,48

arterial pressure during CABG is safe and im- Postoperative systolic dysfunction and arrhyth-

proves outcomes.42 Charlson et al.43 suggested that mias are associated with an increased incidence

intraoperative blood pressure should be evalu- of postoperative stroke.1,79 Therefore, electrolyte

ated in relation to preoperative blood pressure; levels and fluid volume should be optimized, and

they reported that prolonged changes of more the patient must be closely monitored for signs

than 20 mm Hg or 20% in relation to preopera- of heart failure and arrhythmias during the post-

tive levels result in perioperative complications. operative period. It is also helpful to encourage

Efforts to match intraoperative and early post- early postoperative mobility and implement pro-

operative blood pressure to the patients preop- phylactic measures to prevent deep-vein throm-

erative range can reduce the risks of periopera- bosis. A paradoxical embolism leading to stroke

tive stroke and death.27 may occur in patients with a right-to-left shunt.

The management of the patients temperature Finally, there is evidence that initiation of anti-

during surgery also influences outcomes. A re- platelet therapy such as aspirin after cardiac and

n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007 711

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

carotid surgeries reduces the incidence of post- thrombectomy or embolectomy in patients with

operative stroke without increasing the odds of perioperative stroke. However, these techniques

bleeding complications.49,50 There is also evidence may be useful in the postoperative setting, espe-

that supports the preoperative use of statins, ir- cially when the use of intraarterial thrombolysis

respective of the patients lipid profile, to reduce is contraindicated. The limited window for imple-

the risk of perioperative stroke in patients under- menting these interventions highlights the impor-

going cardiovascular surgery.51 tance of rapid recognition of perioperative stroke

and immediate neurologic consultation.

Management

In patients who have recently undergone major F u t ur e Dir ec t ions

surgery, treatment with intravenous t-PA is con-

traindicated because of an increased risk of bleed- Preoperative prophylaxis against perioperative

ing. However, intraarterial administration of t-PA stroke is an appealing concept. A few random-

and endovascular mechanical clot disruption are ized trials have assessed the effect of neuropro-

alternative options. A few case series suggest that tective drugs on the risk of stroke and cognitive

the use of intraarterial thrombolysis within 6 hours decline among patients undergoing CABG.54-56

after the onset of a perioperative stroke is rela- Preoperative administration of statins51 or beta-

tively safe.52,53 In a study of 36 patients who re- blockers30 does appear to reduce the incidence of

ceived intraarterial t-PA after a perioperative stroke, stroke and cognitive decline after CABG. There is

partial to complete recanalization was achieved also some evidence, albeit controversial, that the

in 80% of the patients, 38% had no symptoms or antifibrinolytic agent aprotinin may have similar

only slight disability after discharge, and the mor- effects.56 These results indicate that neuropro-

tality rate was similar to that reported in nonsur- tection may be successful in the perioperative set-

gical patients treated with intraarterial throm- ting and that it merits further investigation. Ran-

bolysis.53 Bleeding at the surgical site occurred in domized, controlled clinical trials are also needed

17% of the patients. Most of this bleeding was to identify the best preventive and management

minor. Intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 25% strategies for perioperative stroke.

of the patients; however, only 8% had worsening Dr. Selim reports receiving grant support from Cierra. No

other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was

symptoms. Intracranial hemorrhage was most reported.

common in patients who underwent a cranioto-

my. There are few data on the use of mechanical

references

1. Bucerius J, Gummert JF, Borger MA, view of the literature. Eur J Vasc Endovasc 12. Likosky DS, Caplan LR, Weintraub RM,

et al. Stroke after cardiac surgery: a risk Surg 2002;23:283-94. et al. Intraoperative and postoperative vari-

factor analysis of 16,184 consecutive adult 7. McKhann GM, Grega MA, Borowicz ables associated with strokes following

patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:472-8. LM Jr, Baumgartner WA, Selnes OA. Stroke cardiac surgery. Heart Surg Forum 2004;7:

2. Kam PC, Calcroft RM. Peri-operative and encephalopathy after cardiac surgery: E271-E276.

stroke in general surgical patients. Anaes- an update. Stroke 2006;37:562-71. 13. Hogue CW Jr, Murphy SF, Schechtman

thesia 1997;52:879-83. 8. Limburg M, Wijdicks EF, Li H. Ische KB, Davila-Roman VG. Risk factors for

3. Gutierrez IZ, Barone DL, Makula PA, mic stroke after surgical procedures: clini- early or delayed stroke after cardiac sur-

Currier C. The risk of perioperative stroke cal features, neuroimaging, and risk fac- gery. Circulation 1999;100:642-7.

in patients with asymptomatic carotid tors. Neurology 1998;50:895-901. 14. Dixon B, Santamaria J, Campbell D.

bruits undergoing peripheral vascular sur- 9. Restrepo L, Wityk RJ, Grega MA, et al. Coagulation activation and organ dysfunc-

gery. Am Surg 1987;53:487-9. Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted mag- tion following cardiac surgery. Chest 2005;

4. Nosan DK, Gomez CR, Maves MD. Peri- netic resonance imaging of the brain before 128:229-36.

operative stroke in patients undergoing and after coronary artery bypass grafting 15. Paramo JA, Rifon J, Llorens R, Casares

head and neck surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol surgery. Stroke 2002;33:2909-15. J, Paloma MJ, Rocha E. Intra- and postop-

Laryngol 1993;102:717-23. 10. Brooker RF, Brown WR, Moody DM, erative fibrinolysis in patients undergoing

5. Bond R, Rerkasem K, Shearman CP, et al. Cardiotomy suction: a major source cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Haemo-

Rothwell PM. Time trends in the published of brain lipid emboli during cardiopul- stasis 1991;21:58-64.

risks of stroke and death due to endarter- monary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65: 16. Hinterhuber G, Bohler K, Kittler H,

ectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. 1651-5. Quehenberger P. Extended monitoring of

Cerebrovasc Dis 2004;18:37-46. 11. Likosky DS, Marrin CA, Caplan LR, et hemostatic activation after varicose vein

6. Naylor AR, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM, Bell al. Determination of etiologic mechanisms surgery under general anesthesia. Derma-

PR. Carotid artery disease and stroke dur- of strokes secondary to coronary artery by- tol Surg 2006;32:632-9.

ing coronary artery bypass: a critical re- pass graft surgery. Stroke 2003;34:2830-4. 17. van Wermeskerken GK, Lardenoye JW,

712 n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

Hill SE, et al. Intraoperative physiologic lation in patients undergoing heart sur- Ebrahim S. Hypothermia to reduce neuro-

variables and outcome in cardiac surgery: gery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;4: logical damage following coronary artery

Part II. Neurologic outcome. Ann Thorac CD003611. bypass surgery. Cochrane Database Syst

Surg 2000;69:1077-83. 31. Epstein AE, Alexander JC, Gutterman Rev 2001;1:CD002138.

18. Charlesworth DC, Likosky DS, Marrin DD, Maisel W, Wharton JM. Anticoagula- 45. Gandhi GY, Nuttall GA, Abel MD, et

CA, et al. Development and validation of a tion: American College of Chest Physicians al. Intraoperative hyperglycemia and peri-

prediction model for strokes after coro- guidelines for the prevention and man- operative outcomes in cardiac surgery pa-

nary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac agement of postoperative atrial fibrilla- tients. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:862-6.

Surg 2003;76:436-43. tion after cardiac surgery. Chest 2005;128: 46. Krinsley JS. Effect of an intensive glu-

19. Gerraty RP, Gates PC, Doyle JC. Carotid Suppl 2:24S-27S. cose management protocol on the mortal-

stenosis and perioperative stroke risk in 32. Maulaz AB, Bezerra DC, Michel P, Bo- ity of critically ill adult patients. Mayo Clin

symptomatic and asymptomatic patients gousslavsky J. Effect of discontinuing as- Proc 2004;79:992-1000. [Erratum, Mayo

undergoing vascular or coronary surgery. pirin therapy on the risk of brain ischemic Clin Proc 2005;80:1101.]

Stroke 1993;24:1115-8. stroke. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1217-20. 47. Albert AA, Beller CJ, Walter JA, et al.

20. Chaturvedi S, Bruno A, Feasby T, et al. 33. Genewein U, Haeberli A, Straub PW, Preoperative high leukocyte count: a novel

Carotid endarterectomy an evidence- Beer JH. Rebound after cessation of oral risk factor for stroke after cardiac sur-

based review: report of the Therapeutics anticoagulant therapy: the biochemical evi- gery. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1550-7.

and Technology Assessment Subcommit- dence. Br J Haematol 1996;92:479-85. 48. Lamm G, Auer J, Weber T, Berent R, Ng

tee of the American Academy of Neurolo- 34. Dunn AS, Turpie AG. Perioperative C, Eber B. Postoperative white blood cell

gy. Neurology 2005;65:794-801. management of patients receiving oral count predicts atrial fibrillation after car-

21. Das SK, Brow TD, Pepper J. Continuing anticoagulants: a systematic review. Arch diac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth

controversy in the management of concom- Intern Med 2003;163:901-8. 2006;20:51-6.

itant coronary and carotid disease: an over- 35. Larson BJ, Zumberg MS, Kitchens CS. 49. Mangano DT. Aspirin and mortality

view. Int J Cardiol 2000;74:47-65. A feasibility study of continuing dose- from coronary bypass surgery. N Engl

22. Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, et reduced warfarin for invasive procedures J Med 2002;347:1309-17.

al. Protected carotid-artery stenting ver- in patients with high thromboembolic risk. 50. Engelter S, Lyrer P. Antiplatelet ther-

sus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. Chest 2005;127:922-7. apy for preventing stroke and other vas-

N Engl J Med 2004;351:1493-501. 36. Dunn AS, Wisnivesky J, Ho W, Moore cular events after carotid endarterecto-

23. Mackey AE, Abrahamowicz M, Lan- C, McGinn T, Sacks HS. Perioperative man- my. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;3:

glois Y, et al. Outcome of asymptomatic agement of patients on oral anticoagu- CD001458.

patients with carotid disease. Neurology lants: a decision analysis. Med Decis Mak- 51. Durazzo AE, Machado FS, Ikeoka DT,

1997;48:896-903. ing 2005;25:387-97. et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events

24. Birincioglu CL, Bayazit M, Ulus AT, 37. OKeefe JH Jr, Allan JJ, McCallister BD, after vascular surgery with atorvastatin:

Bardakci H, Kucuker SA, Tasdemir O. Ca- et al. Angioplasty versus bypass surgery a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:

rotid disease is a risk factor for stroke in for multivessel coronary artery disease 967-75.

coronary bypass operations. J Card Surg with left ventricular ejection fraction < or 52. Moazami N, Smedira NG, McCarthy

1999;14:417-23. = 40%. Am J Cardiol 1993;71:897-901. PM, et al. Safety and efficacy of intraarte-

25. Molloy J, Markus HS. Asymptomatic 38. Sharony R, Grossi EA, Saunders PC, et rial thrombolysis for perioperative stroke

embolization predicts stroke and TIA risk al. Propensity case-matched analysis of after cardiac operation. Ann Thorac Surg

in patients with carotid artery stenosis. off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting 2001;72:1933-7.

Stroke 1999;30:1440-3. in patients with atheromatous aortic dis- 53. Chalela JA, Katzan I, Liebeskind DS,

26. Soinne L, Helenius J, Tatlisumak T, et ease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;127: et al. Safety of intra-arterial thrombolysis

al. Cerebral hemodynamics in asymptom- 406-13. in the postoperative period. Stroke 2001;

atic and symptomatic patients with high- 39. Lev-Ran O, Braunstein R, Sharony R, 32:1365-9.

grade carotid stenosis undergoing carotid et al. No-touch aorta off-pump coronary 54. Taggart DP, Browne SM, Wade DT,

endarterectomy. Stroke 2003;34:1655-61. surgery: the effect on stroke. J Thorac Car- Halligan PW. Neuroprotection during car-

27. Gold JP, Torres KE, Maldarelli W, diovasc Surg 2005;129:307-13. diac surgery: a randomised trial of a platelet

Zhuravlev I, Condit D, Wasnick J. Improv- 40. Breen P, Park KW. General anesthesia activating factor antagonist. Heart 2003;

ing outcomes in coronary surgery: the im- versus regional anesthesia. Int Anesthe- 89:897-900.

pact of echo-directed aortic cannulation siol Clin 2002;40:61-71. 55. Arrowsmith JE, Harrison MJ, New-

and perioperative hemodynamic manage- 41. Turner BK, Wakim JH, Secrest J, Zach- man SP, Stygall J, Timberlake N, Pugsley

ment in 500 patients. Ann Thorac Surg ary R. Neuroprotective effects of thiopen- WB. Neuroprotection of the brain during

2004;78:1579-85. tal, propofol, and etomidate. AANA J 2005; cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized

28. Wimmer-Greinecker G. Reduction of 73:297-302. trial of remacemide during coronary ar-

neurologic complications by intra-aortic 42. Gold JP, Charlson ME, Williams-Rus- tery bypass in 171 patients. Stroke 1998;

filtration in patients undergoing combined so P, et al. lmprovement of outcomes after 29:2357-62.

intracardiac and CABG procedures. Eur coronary artery bypass: a randomized trial 56. Sedrakyan A, Treasure T, Elefteriades

J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;23:159-64. comparing intraoperative high versus low JA. Effect of aprotinin on clinical outcomes

29. Lahtinen J, Biancari F, Salmela E, et mean arterial pressure. J Thorac Cardio- in coronary artery bypass graft surgery:

al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation is a ma- vasc Surg 1995;110:1302-11. a systematic review and meta-analysis of

jor cause of stroke after on-pump coronary 43. Charlson ME, MacKenzie CR, Gold JP, randomized clinical trials. J Thorac Car-

artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg Ales KL, Topkins M, Shires GT. Intraop- diovasc Surg 2004;128:442-8.

2004;77:1241-4. erative blood pressure: what patterns iden- Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society.

30. Crystal E, Garfinkle MS, Connolly SS, tify patients at risk for postoperative com-

Ginger TT, Sleik K, Yusuf SS. Interventions plications? Ann Surg 1990;212:567-80.

for preventing post-operative atrial fibril- 44. Rees K, Beranek-Stanley M, Burke M,

n engl j med 356;7 www.nejm.org february 15, 2007 713

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on December 18, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2007 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Вам также может понравиться

- Complications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The Survival HandbookОт EverandComplications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The Survival HandbookAlistair LindsayОценок пока нет

- Perioperative Stroke BJA 2021Документ7 страницPerioperative Stroke BJA 2021lim sjОценок пока нет

- 33 Spinal Cord InjuryДокумент17 страниц33 Spinal Cord InjuryMiguel SanJuanОценок пока нет

- ESC 2020 Infective Endocarditis and Neurologic Events - Indications and Timing For Surgical InterventionsДокумент8 страницESC 2020 Infective Endocarditis and Neurologic Events - Indications and Timing For Surgical InterventionsJeffry HaryantoОценок пока нет

- Ehv 217Документ8 страницEhv 217Said Qadaru AОценок пока нет

- Perioperative Management of Heart Transplantation A Clinical ReviewДокумент18 страницPerioperative Management of Heart Transplantation A Clinical ReviewMichael PimentelОценок пока нет

- Spinal Injury CordДокумент10 страницSpinal Injury Cordeleanai limaОценок пока нет

- Ibrain - 2022 - Wei - Cerebral Infarction After Cardiac SurgeryДокумент9 страницIbrain - 2022 - Wei - Cerebral Infarction After Cardiac Surgerygra ndynОценок пока нет

- New Neuro 3Документ4 страницыNew Neuro 3yous1786Оценок пока нет

- Ehad 019Документ20 страницEhad 019gyt42yx8g2Оценок пока нет

- Preope Mayo Clinic 2020Документ16 страницPreope Mayo Clinic 2020claauherreraОценок пока нет

- 56 Anaesthesia For Carotid Endarterectomy PDFДокумент10 страниц56 Anaesthesia For Carotid Endarterectomy PDFHarish BhatОценок пока нет

- Anesthesia Management of Ophthalmic Surgery in Geriatric Patients PDFДокумент11 страницAnesthesia Management of Ophthalmic Surgery in Geriatric Patients PDFtiaraleshaОценок пока нет

- Postoperative Pituitary Management Ausiello 2008Документ11 страницPostoperative Pituitary Management Ausiello 2008api-229617613Оценок пока нет

- NeuroVISION ArticleДокумент8 страницNeuroVISION ArticleDanielle de Sa BoasquevisqueОценок пока нет

- Critical Care Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Ischemic StrokeДокумент21 страницаCritical Care Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Ischemic StrokeAnonymous QLadTClydkОценок пока нет

- Ecg Monitoring of Myocardial Ischemia BR 9066445 enДокумент74 страницыEcg Monitoring of Myocardial Ischemia BR 9066445 enAlicia GarcíaОценок пока нет

- Preoperative Evaluation For Non-Cardiac Surgery: AK GhoshДокумент6 страницPreoperative Evaluation For Non-Cardiac Surgery: AK GhoshAshvanee Kumar SharmaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal TutKlinДокумент9 страницJurnal TutKlinFadhil AbdillahОценок пока нет

- Gs 10 03 1135Документ12 страницGs 10 03 1135Ashu AberaОценок пока нет

- Stroke and Encephalopathy After Cardiac SurgeryДокумент11 страницStroke and Encephalopathy After Cardiac Surgeryilmiah neurologiОценок пока нет

- Mechanical Complication of Myocardial InfactionДокумент9 страницMechanical Complication of Myocardial InfactionDaniela VillarОценок пока нет

- Cardiac Surgery - Postoperative ArrhythmiasДокумент9 страницCardiac Surgery - Postoperative ArrhythmiaswanariaОценок пока нет

- Anesthesia For Carotid Endarterectomy: Where Do We Stand at Present?Документ12 страницAnesthesia For Carotid Endarterectomy: Where Do We Stand at Present?Lil_QuinceОценок пока нет

- ListjadwalДокумент6 страницListjadwalAldilla RizkyОценок пока нет

- TRAUMAДокумент18 страницTRAUMAMicaela BenavidesОценок пока нет

- Nihms-Guidelines For Uses of AnticoagulantsДокумент16 страницNihms-Guidelines For Uses of AnticoagulantsDilip Kumar MОценок пока нет

- Neurogenic Shock - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfДокумент6 страницNeurogenic Shock - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfzefri suhendarОценок пока нет

- CNS Neuroscience Therapeutics - 2022 - An - Potential NanotheДокумент11 страницCNS Neuroscience Therapeutics - 2022 - An - Potential NanotheNurul 53Оценок пока нет

- Manejo PostparoДокумент17 страницManejo PostparoAngela Moreira ArteagaОценок пока нет

- Cec y Respuesta InflamatoriaДокумент11 страницCec y Respuesta InflamatoriamaritzabericesОценок пока нет

- Intracranial Haemorrhage (ICH) Occurs in About 5% of Patients With IEДокумент5 страницIntracranial Haemorrhage (ICH) Occurs in About 5% of Patients With IETnf-alpha DelusionОценок пока нет

- Complications Predicting Perioperative Mortality in Patients Undergoing Elective Craniotomy A Population Based StudyДокумент11 страницComplications Predicting Perioperative Mortality in Patients Undergoing Elective Craniotomy A Population Based Study49hr84j7spОценок пока нет

- Development of A Simple Algorithm To Guide The Effective Management of Traumatic Cardiac ArrestДокумент5 страницDevelopment of A Simple Algorithm To Guide The Effective Management of Traumatic Cardiac ArrestIrisMarisolОценок пока нет

- Determinants and Outcomes of Stroke Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention by IndicationДокумент8 страницDeterminants and Outcomes of Stroke Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention by Indicationbalqis noorОценок пока нет

- Treating The Acute Stroke Patient As An EmergencyДокумент9 страницTreating The Acute Stroke Patient As An EmergencyAnonymous EAPbx6Оценок пока нет

- Ortodoncia y CirugiaДокумент68 страницOrtodoncia y CirugiaCicse RondanelliОценок пока нет

- 1 s20 S0002934322006295 Main - 221027 - 063744Документ10 страниц1 s20 S0002934322006295 Main - 221027 - 063744Vaomir DiazОценок пока нет

- 1.postoperative Arrhythmias After Cardiac SurgeryДокумент16 страниц1.postoperative Arrhythmias After Cardiac Surgeryganda gandaОценок пока нет

- Advances in Acute Ischemic Stroke TherapyДокумент22 страницыAdvances in Acute Ischemic Stroke TherapylorenaОценок пока нет

- Ref 3. Anaesthesia - 2018 - Hewson - Peripheral Nerve Injury Arising in Anaesthesia PracticeДокумент10 страницRef 3. Anaesthesia - 2018 - Hewson - Peripheral Nerve Injury Arising in Anaesthesia PracticeNabilОценок пока нет

- Stroke in Surgical PatientsДокумент13 страницStroke in Surgical Patientscarlos gordilloОценок пока нет

- 10.1038@s41572 019 0118 8Документ22 страницы10.1038@s41572 019 0118 8Anabel AguilarОценок пока нет

- 2022 The Intensive Care Management of Acute Ischaemic StrokeДокумент9 страниц2022 The Intensive Care Management of Acute Ischaemic StrokeOmar Alejandro Agudelo ZuluagaОценок пока нет

- 2015 Manejo Postquirurgico Del Paciente Con Cirugia Cardiaca Parte IIДокумент20 страниц2015 Manejo Postquirurgico Del Paciente Con Cirugia Cardiaca Parte IIAdiel OjedaОценок пока нет

- Preoperative Evaluation Before NoncardiacДокумент16 страницPreoperative Evaluation Before NoncardiacHercilioОценок пока нет

- Documento 8 Part 9 PostCardiac Arrest Care 2010Документ19 страницDocumento 8 Part 9 PostCardiac Arrest Care 2010jo garОценок пока нет

- 2019 Complication After Epilepsy Surgery AChA InfarctДокумент7 страниц2019 Complication After Epilepsy Surgery AChA InfarctSafitri MuhlisaОценок пока нет

- J Surneu 2005 04 039Документ7 страницJ Surneu 2005 04 039MohitОценок пока нет

- Management of Vasoplegic ShockДокумент16 страницManagement of Vasoplegic ShockxmksmwyspyОценок пока нет

- AKI and CRRT RelationДокумент10 страницAKI and CRRT RelationZainab MotiwalaОценок пока нет

- Lower Extremity Arterial Injuries Over A Six-Year Period: Outcomes, Risk Factors, and ManagementДокумент9 страницLower Extremity Arterial Injuries Over A Six-Year Period: Outcomes, Risk Factors, and ManagementrizcoolОценок пока нет

- Medical Management of StrokeДокумент6 страницMedical Management of StrokemehakОценок пока нет

- Spinal Cord Injury PDFДокумент14 страницSpinal Cord Injury PDFNiaОценок пока нет

- Preoperative Evaluation Before Noncardiac Surgery.Документ16 страницPreoperative Evaluation Before Noncardiac Surgery.Paloma AcostaОценок пока нет

- Antikoagulan JurnalДокумент5 страницAntikoagulan JurnalansyemomoleОценок пока нет

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.01.005Документ42 страницыAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.01.005Irvin MarcelОценок пока нет

- Journal NeuroДокумент6 страницJournal NeuroBetari DhiraОценок пока нет

- Post-Resuscitation Shock: Recent Advances in Pathophysiology and TreatmentДокумент11 страницPost-Resuscitation Shock: Recent Advances in Pathophysiology and TreatmentblanquishemОценок пока нет

- CraniectomyДокумент6 страницCraniectomyale saenzОценок пока нет

- Snake Bite Case Series Dec 2012Документ25 страницSnake Bite Case Series Dec 2012kucingkucingОценок пока нет

- Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex, Generalized: (Type The Document Title)Документ8 страницEpidermolysis Bullosa Simplex, Generalized: (Type The Document Title)kucingkucingОценок пока нет

- Epidermolysis Bullosa, Junctional, Herlitz Type: (Type The Document Title)Документ11 страницEpidermolysis Bullosa, Junctional, Herlitz Type: (Type The Document Title)kucingkucingОценок пока нет

- Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex, Generalized: (Type The Document Title)Документ9 страницEpidermolysis Bullosa Simplex, Generalized: (Type The Document Title)kucingkucingОценок пока нет

- Kindler Syndrome: (Type The Document Title)Документ6 страницKindler Syndrome: (Type The Document Title)kucingkucingОценок пока нет

- Penyuluhan Cara Pencegahan Panu (Ptyriasis Vesikolor) Di Posyandu RA Hidayah SeketengДокумент1 страницаPenyuluhan Cara Pencegahan Panu (Ptyriasis Vesikolor) Di Posyandu RA Hidayah SeketengkucingkucingОценок пока нет

- Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Review ArticleДокумент10 страницAneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Review ArticlekucingkucingОценок пока нет

- Imabalacat DocuДокумент114 страницImabalacat DocuJänrëýMåmårìlSälängsàngОценок пока нет

- 25 Middlegame Concepts Every Chess Player Must KnowДокумент2 страницы25 Middlegame Concepts Every Chess Player Must KnowKasparicoОценок пока нет

- Acting White 2011 SohnДокумент18 страницActing White 2011 SohnrceglieОценок пока нет

- Applying For A Job: Pre-ReadingДокумент5 страницApplying For A Job: Pre-ReadingDianitta MaciasОценок пока нет

- Traditional Perceptions and Treatment of Mental Illness in EthiopiaДокумент7 страницTraditional Perceptions and Treatment of Mental Illness in EthiopiaifriqiyahОценок пока нет

- Praise and Worship Songs Volume 2 PDFДокумент92 страницыPraise and Worship Songs Volume 2 PDFDaniel AnayaОценок пока нет

- ABARI-Volunteer Guide BookДокумент10 страницABARI-Volunteer Guide BookEla Mercado0% (1)

- Origin ManualДокумент186 страницOrigin ManualmariaОценок пока нет

- Jul - Dec 09Документ8 страницJul - Dec 09dmaizulОценок пока нет

- Studies On Drying Kinetics of Solids in A Rotary DryerДокумент6 страницStudies On Drying Kinetics of Solids in A Rotary DryerVinh Do ThanhОценок пока нет

- Research FinalДокумент55 страницResearch Finalkieferdem071908Оценок пока нет

- Diogenes Laertius-Book 10 - Epicurus - Tomado de Lives of The Eminent Philosophers (Oxford, 2018) PDFДокумент54 страницыDiogenes Laertius-Book 10 - Epicurus - Tomado de Lives of The Eminent Philosophers (Oxford, 2018) PDFAndres Felipe Pineda JaimesОценок пока нет

- IM1 Calculus 2 Revised 2024 PUPSMBДокумент14 страницIM1 Calculus 2 Revised 2024 PUPSMBEunice AlonzoОценок пока нет

- PlateNo 1Документ7 страницPlateNo 1Franz Anfernee Felipe GenerosoОценок пока нет

- Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction and Acute Management StrategiesДокумент11 страницPathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction and Acute Management StrategiesnwabukingzОценок пока нет

- Cobol v1Документ334 страницыCobol v1Nagaraju BОценок пока нет

- Detail Design Drawings: OCTOBER., 2017 Date Span Carriage WayДокумент26 страницDetail Design Drawings: OCTOBER., 2017 Date Span Carriage WayManvendra NigamОценок пока нет

- VimДокумент258 страницVimMichael BarsonОценок пока нет

- Tutorial Chapter 5 - Power System ControlДокумент2 страницыTutorial Chapter 5 - Power System ControlsahibОценок пока нет

- AДокумент54 страницыActyvteОценок пока нет

- SIVACON 8PS - Planning With SIVACON 8PS Planning Manual, 11/2016, A5E01541101-04Документ1 страницаSIVACON 8PS - Planning With SIVACON 8PS Planning Manual, 11/2016, A5E01541101-04marcospmmОценок пока нет

- China Training WCDMA 06-06Документ128 страницChina Training WCDMA 06-06ryanz2009Оценок пока нет

- Practice - Test 2Документ5 страницPractice - Test 2Nguyễn QanhОценок пока нет

- CISF Manual Final OriginalДокумент17 страницCISF Manual Final OriginalVaishnavi JayakumarОценок пока нет

- Ateneo de Manila University: Submitted byДокумент5 страницAteneo de Manila University: Submitted byCuster CoОценок пока нет

- Data MiningДокумент28 страницData MiningGURUPADA PATIОценок пока нет

- Crypto Wall Crypto Snipershot OB Strategy - Day Trade SwingДокумент29 страницCrypto Wall Crypto Snipershot OB Strategy - Day Trade SwingArete JinseiОценок пока нет

- Chapter 10 Tute Solutions PDFДокумент7 страницChapter 10 Tute Solutions PDFAi Tien TranОценок пока нет

- Img 20150510 0001Документ2 страницыImg 20150510 0001api-284663984Оценок пока нет

- Perdarahan Uterus AbnormalДокумент15 страницPerdarahan Uterus Abnormalarfiah100% (1)