Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Psi Ho Logie

Загружено:

Alexandru ReleaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Psi Ho Logie

Загружено:

Alexandru ReleaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SO WHAT?

If we wish to act rationally, we ought to make decisions by weighing the

probability and desirability of the various outcomes that would result from

deciding one way or the other. The manner in which those outcomes are

portrayed should make no difference. The water in a glass that is described

as half-full or half-empty either way you will still drink the same amount of water.

However, the human mind turns out to be significantly swayed by how potential

outcomes are portrayed.

There are many other examples of how the framing of alternatives can

influence our decisions. One is our use of psychic budgets. For example, if buying a

new house, we might be prepared to spend more on things like garden gnomes than

we would if the house were already ours. The reason is that, before the house is

bought, the cost of the gnomes falls under the budget for the entire house. However,

after the house is bought, the cost of the gnomes falls under the tighter budget of

everyday expenses, and so seems comparatively extravagant. Needless to add, sales

professionals are happy to exploit our budgeting biases, craftily inflating the asking

price for accessories to a major purchase.

Another example of framing effects involves presenting alternative options

as either maintaining the status quo or as altering it. Suppose you

have a zero chance of developing a fatal disease. How much would you pay

to avoid having a 1 in 1,000 chance of developing it? Most people say that

they would be prepared to pay several thousand dollars. However, now suppose

that you already have a 1 in a 1,000 chance of developing that disease.

How much would you now pay to reduce that risk to zero?

Inconsistently, most people say that they would be prepared to pay only a

few hundred dollars. Why is this?

An answer is provided by the fourth and final postulate of prospect theory:

The loss of a benefit is considered more disadvantageous than the

gain of that benefit is considered advantageous. One implication of this

postulate is that, to induce people to accept a gamble involving an equal

chance of winning or losing, it is necessary to award them more for winning

than to penalize them for losing. For example, only a third of people

accept an equal chance of winning $200 or losing $100.Another example are the

betting houses if you gamble 2 $ you might win 10$.

The existence of this bias in favor of the status quo can explain why people

pay more to avoid potential risks than they do to eliminate preexisting

ones.

But why do costs psychologically outweigh benefits?

Bad experiences have a more powerful effect on us than good experiences .There have

been studies that showed that 95 % of us will take action for a bad experience such as

a bad service or a poor quality product , 1 in 3 people under 24 will share it online

and over 25 % of us will tell a friend to never to use that product again.

Another possibility is that the tendency to weigh costs more heavily than gains may

have evolved over time because it conferred a survival benefit on our forefathers. This

is not to deny that people vary considerably in their penchant for

risk-taking. For example, people with high self-esteem take more risks on

average than people with low .Another study shows that people who listen to fast

music are more probably to take risks than the ones who listen to calm music.

So If prospect theory is true, then why is gambling such a popular pastime?

The answer is that most amounts gambled are psychologically trivial. If only very

large bets could be laid, gambling would disappear overnight. Prospect theory

properly applies only when significant amounts of money are involved.

AFTERTHOUGHTS

This kind of mental duality also emerges when people are alerted to

other cognitive biases, in particular those that involve probability judgments.

Consider a lottery in which the winning 6 numbers are to be chosen

at random from a pool of 36 numbers. There are two tickets for sale.

One features the numbers "1,2,3,4,5,6," the other, "2,18,17,29,4,35."

Which ticket would you buy? second ticket

The odds of a ticket with random numbers winning certainly seem better than the odds

of a ticket with consecutive numbers winning

The ticket featuring the randomly numbers is chosen on the basis of its similarity to

past winning tickets, not on the basis of correct statistical logic.

How can we make sense of the fact that half our mind can understand

something while the other half cannot? One way to view the matter is by

analogy with perceptual illusions .For example Rabbitduck illusion

Perceptual illusions of this sort cannot be eliminated from consciousness because our

brains are physiologically hard-wired to produce them. No amount of effort can

reason them out of existence. Their illusory quality can only be abstractly pondered.

The same may be true of many of our cognitive biases.

CONCLUSIONS

People avoid risks when they stand to gain, but take risks when they stand

to lose. Therefore how a choice is framed, in terms of loss or gain, can

influence how people choose, over and above the objective consequences

of choosing one way or the other.

Вам также может понравиться

- Fatal1ty FM2A88X+ Killer SeriesДокумент77 страницFatal1ty FM2A88X+ Killer SeriesAlexandru ReleaОценок пока нет

- QuotesДокумент2 страницыQuotesAlexandru ReleaОценок пока нет

- Research On Effect of Beijing Post-Olympic Sports Industry To China's Economic DevelopmentДокумент6 страницResearch On Effect of Beijing Post-Olympic Sports Industry To China's Economic DevelopmentAlexandru ReleaОценок пока нет

- Economics in One LessonДокумент4 страницыEconomics in One LessonAlexandru ReleaОценок пока нет

- Never Push A Loyal Person To The Point Where They No Longer Give A Fuck! in Times of Peace The Warlike Man Attacks HimselfДокумент1 страницаNever Push A Loyal Person To The Point Where They No Longer Give A Fuck! in Times of Peace The Warlike Man Attacks HimselfAlexandru ReleaОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Behavior Therapy SlidesДокумент33 страницыBehavior Therapy SlidesSeenu XavierОценок пока нет

- Annual Self-Evaluation Form - Manager: Date: Employee Name: Evaluation Area NotesДокумент3 страницыAnnual Self-Evaluation Form - Manager: Date: Employee Name: Evaluation Area NotesromeeОценок пока нет

- Managemet MCQs-2Документ15 страницManagemet MCQs-2chikka28Оценок пока нет

- The Human Element in Safety PDFДокумент16 страницThe Human Element in Safety PDFKentDemeterio0% (1)

- An Emerging Discipline - Neil LeiperДокумент5 страницAn Emerging Discipline - Neil LeiperDeniseRodriguesОценок пока нет

- An Attitude Is A Hypothetical Construct That Represents An IndividualДокумент5 страницAn Attitude Is A Hypothetical Construct That Represents An IndividualRadhika ShenoiОценок пока нет

- The Tripartite Soul Plato and Freud (1) 2Документ12 страницThe Tripartite Soul Plato and Freud (1) 2Catherine BlakeОценок пока нет

- Assig of English For Young Children.Документ19 страницAssig of English For Young Children.S.ANNE MARY100% (1)

- Soul Theory of The BuddhistsДокумент62 страницыSoul Theory of The BuddhistsAadad100% (1)

- XAT Question PaperДокумент64 страницыXAT Question PaperAnkur SrivastavaОценок пока нет

- Family Health Nursing Care ProcessДокумент2 страницыFamily Health Nursing Care ProcessAnnalisa TellesОценок пока нет

- Middle Childhood Reflection Paper FinalДокумент4 страницыMiddle Childhood Reflection Paper Finalapi-349363475100% (4)

- Organizational CultureДокумент15 страницOrganizational Culturetuffy0234Оценок пока нет

- Aristotle's Theory of Practical Wisdom - Ricardo Parellada PDFДокумент18 страницAristotle's Theory of Practical Wisdom - Ricardo Parellada PDFjusrmyrОценок пока нет

- Reflective AssignmentДокумент5 страницReflective AssignmentVictor Murambiwa100% (3)

- PSY 202 Essay On Self-Determination TheoryДокумент2 страницыPSY 202 Essay On Self-Determination TheorySlimОценок пока нет

- Soal What Makes A Leader1 AnswerДокумент5 страницSoal What Makes A Leader1 AnswerRudy Setiawan100% (1)

- Multiple Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods in Economics: AnДокумент34 страницыMultiple Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods in Economics: AnLeonardo OliveiraОценок пока нет

- David Seamon, Robert Mugerauer (Auth.), David Seamon, Robert Mugerauer (Eds.) - Dwelling, Place and Environment - Towards A Phenomenology PDFДокумент303 страницыDavid Seamon, Robert Mugerauer (Auth.), David Seamon, Robert Mugerauer (Eds.) - Dwelling, Place and Environment - Towards A Phenomenology PDFBryan Hernández100% (1)

- Relationships PresentationДокумент14 страницRelationships PresentationmnogadeОценок пока нет

- Chapter 8Документ9 страницChapter 8Khan AbdullahОценок пока нет

- Learning and Teaching Real World Problem Solving in School MathematicsДокумент210 страницLearning and Teaching Real World Problem Solving in School MathematicsCathdeeОценок пока нет

- Communication ProcessДокумент4 страницыCommunication Processanon_189062430Оценок пока нет

- A History of Management ThoughtДокумент45 страницA History of Management ThoughtDr-Sajjad Ul Aziz QadriОценок пока нет

- The Second Machine AgeДокумент11 страницThe Second Machine AgeAayush DesaiОценок пока нет

- Leadrship and Learning Gordon Dryden The Learning RevolutionДокумент4 страницыLeadrship and Learning Gordon Dryden The Learning RevolutionTeleerTV VIDEO ESCUELA TVОценок пока нет

- Barriers and Bridges To CreativityДокумент18 страницBarriers and Bridges To CreativityPadmaraj MОценок пока нет

- The Positive and Negative Impact of Inclusive LeadershipДокумент9 страницThe Positive and Negative Impact of Inclusive LeadershipAmbreen ZainebОценок пока нет

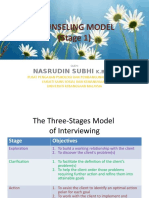

- Counseling Model (Stage 1) : Nasrudin SubhiДокумент30 страницCounseling Model (Stage 1) : Nasrudin SubhiNoor A'isyahОценок пока нет

- FS 2Документ62 страницыFS 2Courtney Love Arriedo OridoОценок пока нет