Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The World of The Fearful

Загружено:

Oscar Armando Béjar GuerreroОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The World of The Fearful

Загружено:

Oscar Armando Béjar GuerreroАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 449

Margareta HYDN

The World of the Fearful: Battered Womens

Narratives of Leaving Abusive Husbands

It is often suggested that battered women do not leave their abusive husbands because of

fear. In this article, it is argued that fear of the husband is not only something that

hampers women, but that it also could be regarded as a form of resistance on the part of

women. Fear does not necessarily include action, but contains an unarticulated knowledge

of what is wanted and what is unwanted. Based on interviews with 10 battered women at

the time of leaving their abusers, and two years on, the article analyzes the fear that con-

stituted a major part of the break-up process. Drawing on Foucaults conceptualization of

power, the accounts of fear were read as narratives of resistance to violence. Knowledge

about the different ways that a battered woman can express her resistance to violence

increases the prospects for researchers and professional and lay helpers to more ade-

quately address the complexity of the abuse of women.

INTRODUCTION

Why doesnt she leave? This is one of the most common questions raised about

battered women. The question implies dissociation from the violent event but

also an undertone of criticism of its victim: a woman who continues to live with

a man who batters her cannot be totally normal. The question is founded on the

incorrect assumption that a battered woman does in fact stay. She does not. Every

time he beats her she thinks, I dont want to experience this, I dont want to be

here. In her mind she leaves immediately. For some women, the break-up is

psychological the woman removes herself from the situation in her mind and

makes herself unreachable psychologically (Hydn, 1995a). For other women,

the violent situation ends with their physically leaving temporarily or forever

(Mullender, 1996).

Feminism & Psychology 1999 SAGE (London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi),

Vol. 9(4): 449469.

[0959-3535(199911)9:4;449469;010340]

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 450

450 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

This article deals with the women who do (physically) leave. The aim of the

article is to indirectly problematize the question of why some women do not leave

by analyzing one of the themes fear which constitutes a part of the break-up.

The origin of the article is a study whereby, during two years of interviewing, I

took part in battered womens prospective narratives about leaving violent

marriages, starting right after the break-up. The aim of the study was to describe

the psychological process of breaking up from an abusive husband and to find

answers to questions such as: in what way do the women account for the decision

to leave? What happened after they left? The study and its theoretical basis are

closely connected to my earlier work on battered women (Hydn, 1994, 1995a,

1995b; Hydn and McCarthy, 1994).

Aside from working as a researcher, I am also a psychotherapist. Over the

years my work has been devoted principally to psychotherapy with women

suffering from traumatic experiences of sexual abuse and/or marital violence. I

undertook my doctoral studies with a conviction that theoretical studies in social

science would bring knowledge and insights to battered womens problems, and

that my acquiring of methodological skills would enable me to undertake my own

studies. The techniques and methods of psychotherapy are developed in order to

focus the inner life and inner development of the individual or the family. I

wished to expand this perspective and in a more all-embracing way study the

psychological process my patients undertook, the experiences they shared and the

themes and issues that were central in their lives. The common efforts of patient

and therapist, in order for the patient to achieve a higher degree of self-

understanding, are part of what I appreciate most in therapeutic work. In psycho-

therapy with battered women this self-understanding does not reach its full

meaning until it can be transformed into thoughts and actions that help the

woman to gain control over her own life. One of my foremost aims in my

research work is to gain knowledge that can be used for such purposes.

In studying battered womens break-ups, I have worked both theoretically and

empirically in an area that has hardly been touched on before. The dramaturgy

and rhetoric of the break-ups social-psychological process had not previously

captured the interest of researchers of battered women. There have been studies

done in closely associated areas, such as battered womens repeated attempts to

end the violence by reasoning with the husband and making him understand that

he must cease the abuse, by retreating or by seeking the protection and advice of

relatives and friends (Bowker, 1993; Kelly, 1988; Mullender, 1996; Pahl, 1985).

I have learned in my psychotherapeutic work that resistance and break-up are

closely associated with one another. With only a few exceptions (Kelly, 1988;

Wade, 1997), the resistance theme has been almost completely missing from

research on the abuse of women. Subjects such as the function, consequences

and psychological damage of violence have, however, attracted the interest of

feminist-oriented researchers (Eliasson, 1997; Herman, 1992; Lundgren, 1993;

Miller, 1994; Waites, 1993; Walker, 1984, 1994), and criminologists have

studied questions such as the spread of violence and the reasons for it (Gelles,

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 451

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 451

1979; Straus and Gelles, 1990). By studying the break-ups of battered women, I

want to contribute by adding the theme of resistance to the agenda. Studying

battered womens break-ups involves studying how the woman fractures the

mans sphere of power. It involves study of those cases in which the man wields

power over the woman by the use of violence, but has failed to maintain his

power because the woman left him.

There are three parts to the article. In the first part I describe the study of

battered womens break-ups, from which the material is derived. Thereafter

follows the main section of the article, which describes the womens accounts of

fear. The conclusion is a discussion of the significance of women getting the

chance to voice their fears in order to get protection and to deal with the fears,

and the difficulties which meet a presumptive listener/respondent.

THE STUDY

Ten women who sought refuge at a shelter for battered women in Stockholm,

Sweden, after having left an abusive husband, were interviewed on six separate

occasions over a two-year period. All the women had been subjected to repeated

and serious violence in their marriages. Serious violence is defined as violent

actions (for example, kicks, punches, threats with a weapon, attempt to strangle,

rape and so on). Repeated violence means violence that is so frequent that it

has become an integral part of marital life. Women in the group were subjected

to the shelters entry criteria and conditions. For example, women with substance

misuse problems were not admitted.

In the year during which my informants lived in the womens shelter, about 40

women stayed there. The length of their stays varied greatly, from a week or so

up to one year. Two categories of women could be identified by their national

origins. Between 20 percent and 30 percent of the women were of Swedish (or

other Nordic) origin. The divisions did not change significantly over the years.

Socially, this was a comparatively homogeneous group of women from the work-

ing class and the lower middle class. Most of the women did not have strong

economic or professional positions, which influenced their break-ups and their

opportunities for independent lives. The second category was women with a non-

Nordic national origin (7080 percent).1 For linguistic and cultural reasons I

sought my informants in the group of Swedish and Nordic women. I felt that I

would have the best chance of communicating with, and getting the most

comparable material from, this reasonably homogeneous group of women (see

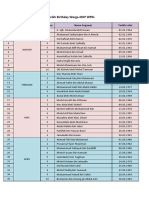

Table 1).

Of my 10 informants, 6 were employed in the public sector; of these, 5 had

lower positions in the area of health and medical care. One of the women was

more educated and worked in private industry; one woman was a student; one

was a housewife; and one was unemployed. The ages of the women varied from

21 to 45 years. Eight of the women were dependent on social welfare for short

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 452

452 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

periods so that they could pay for moving expenses, or to compensate for low sick

pay or a lack of unemployment insurance. Altogether, the women had a total of

16 children at home and 2 grown children. Six of the abusive husbands were of

foreign origin.

TABLE 1

Names of informants (changed to protect their privacy), ages and numbers of children

Anja, 45 Two children (abuser not the father) Fredrika, 21 No children

Bea, 23 Two children (abuser is father of Gun, 27 No children

one of them)

Carolina, 43 Three children Helen, 28 Four children

Danielle, 26 Two children (abuser is father of Isa, 33 Two children

one of them)

Eva, 34 One child (abuser not the father) Jannike, 36 Two children

(abuser is father

of one of them)

The Interview

Each interview lasted approximately one hour and was taped, then subsequently

transcribed. Altogether, this led to a text of about 860 pages. I made my analysis

on the Swedish text. A native English speaker has then translated the excerpts

used in this article into English.

The first interview took place at the womens shelter one or two weeks after

arrival, and subsequent interviews were conducted in the womens homes at

about four-month intervals. Prior to the first interview, I prepared only two

questions: Why do you leave the marriage at this point? and What is your life

like right now; what is most central in your life right now? The second question

was repeated in each of the later interviews, in which I asked: How has your

present life been affected by what you have gone through? and What do you

think about those violent events now?

To encourage free narratives, I chose an open interview style with few

questions formulated in detail. In my form of interviewing, the questions are

primarily aimed at constructing a framework and a relationship within which my

informant could feel free and have the opportunity to discuss her thoughts and

feelings. It is her associations, her inner logic and understanding (or possibly her

lack of inner logic and understanding) of what had happened that I wanted to

access. I have striven to develop a form for interviewing that is built on the

assumption that the research interview can be understood as a relational practice

that places at the informants disposal a framework for developing his/her under-

standing. Such an interview form gives the researcher the opportunity to gain

richer material than the traditional in-depth interview.

I refrained from trying to formulate the womens dilemmas as psychiatric

diagnoses. I wanted to avoid attributing the social conditions under which the

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 453

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 453

woman lived and the psychological processes they were undergoing in the break-

ups to specific qualities in the women themselves. A quality is something that is

an attribute of the person herself; it is something that is lasting and not limited

in time and space. A process is not a quality, but rather a condition, which is

characterized by changeability.2

THE WOMENS FEARS IN A TWO-YEAR PERSPECTIVE

Prior to the Break-up

My opening question Why do you leave the marriage at this point? was

generally met by a short silence and That is a good question, followed by I

really dont know. The women gave me no clear accounts of their decisions to

leave. However, as the interviews proceeded, I got very dramatic accounts of

inner dialogues that took place prior to leaving. Fear was not accounted for as an

issue in these dialogues. The contents were rather about considering whether to

live or to die. The spectre of Death had entered the marital scene and the dialogue

was between him and the woman. She connected her husband to Death as the

collaborator and assumed that he wanted to kill her. This understanding came

to her all of a sudden, sometimes reflecting an actual change in the mans

behaviour, sometimes not. Her voice in the dialogue was the resisting one. Her

decision was not about leaving, but about living.

Prior to this decision there was a period when the women endured by with-

drawing. Outwardly, they tried to be as passive as possible in order to avoid con-

flict, but their inner activity was considerable.

After the Break-up

Undifferentiated and differentiated fear. My second question in the initial inter-

view, What is your life like right now?, got very prompt answers. All of the

women discussed fear as an emotion that dominated their lives completely. Five

of the women brought it up spontaneously, even though the subject had not

specifically been addressed in the interview. Five of the women discussed their

fear more as a result of our conversations. In these cases it was sometimes I who

introduced the theme (What you describe sounds like several different examples

of fear. Is that so?), or the woman herself (What Im talking about here, I notice,

is how scared I am). In a first analysis of the womens narratives, I focused my

work on the basic characteristics of the descriptions of fear. I found the content

of the descriptions quite comprehensive, and various aspects of fear were touched

on. I have chosen to present three of these aspects, primarily because they

recurred frequently in the womens interpretation of their fear. I also chose them

because I consider them to be central, both in setting up a course of treatment and

for the planning of the efforts of police and social services. These three aspects

are:

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 454

454 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

Object of fear

Could vary between:

A general feeling of fear not associated with any object outside the woman

herself

The woman feels both general fear and fear of the husband

The woman is afraid of her husband.

The womans capacity for action in relationship to the fear

Could vary between:

None, aside from staying hidden

Reactive; if she is threatened by the husband she can seek shelter

Self-initiating; she can take the initiative in order to reduce her fear.

Extent of fear

Could vary between:

Overwhelming, completely dominating

Not overwhelming, but plays a major role in the womans life

Background emotion.

The women continued to discuss fear in subsequent interviews. When I

analyzed the womens descriptions of their fear, I found that they changed their

stories over time in a very characteristic way. During the first interview the fear

was not directed at any specific object. Six of the women described a general,

impersonal feeling of fear, and four described both a general fear as well as a fear

of their husbands. Their fears dominated the entire lives of seven of the women.

Eight of the women described themselves as being without capacity for action to

deal with this kind of fear, except by keeping themselves hidden. Two of the

women told of well thought-out systems of how they would be able to protect

themselves if they were to meet their husbands on the street. Most of the women

described the extent of fear in this first interview as though they were over-

whelmed by it; it was an emotion that completely dominated their lives (see

Table 2).

In a second analysis of the womens narratives, I focused my work on an

investigation of the different aspects of fear and on the relationships between

these aspects. I found that they had a characteristic relationship to each other, and

was able to identify two basic kinds of fear, undifferentiated and differentiated. I

have several reasons for emphasizing these. First, the emphasis demonstrates

something of the difficulties and emotional stresses involved in a break-up; it can

put the question of Why doesnt she leave him? into perspective. Second, fear

seems to be an unavoidable part of the break-up. And third, fear seems to be a

complex emotion that changes character with time, which means that the same

woman can experience fear in several different ways in the process of breaking

up.

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 455

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 455

TABLE 2

Changes in the descriptions of fear over a period of time. Number of informants who on

some occasion named fear as a subject (N=10)

Interview Mentions fear Mentions Aspects of fear

fear spon-

taneously

Object of fear Womans Extent

capacity of fear

for action

a b c d e f g h i

1 10 5 6 4 0 8 2 0 7 3 0

2 7 3 1 2 4 2 2 3 1 6 0

3 5 3 0 1 4 0 2 3 0 5 0

4 5 3 0 2 3 0 2 3 0 2 3

5 5 2 0 2 3 0 2 3 0 2 3

6 5 1 0 2 3 0 3 2 0 2 3

Object of fear:

a=A general feeling of fear not associated with any object outside the woman herself

b=The woman feels both general fear and fear of the husband

c=The woman is afraid of her husband

The womans capacity for action:

d=None, aside from staying hidden

e=Reactive; if she is threatened by the husband she can seek shelter

f=Self-initiating; she can take the initiative in order to reduce her fear

Extent of fear:

g=Overwhelming, completely dominating

h=Not overwhelming, but plays a major role in the womans life

i=Background emotion

Two Weeks to Four Months after the Break-up

Undifferentiated fear completely overwhelms the woman as a general feeling,

and is seen as being impossible to deal with. The first of these two basic kinds of

fear I have chosen to call undifferentiated fear. This is a general fear which is not

connected with any object or situation outside the woman herself. The woman is

completely overwhelmed by her fear and sees no opportunity to influence it.

Variations of this type of fear can include her belief in a certain capacity for

action, or that the fear does not completely occupy her. This kind of fear consti-

tuted a dominant theme in the first interview.

In the following excerpt we meet Eva, a 34-year-old woman, in her first inter-

view. I have asked her: Whats going on? Whats central in your life right now?

Eva answers:

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 456

456 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

If I start out with when I first came here, what I was mostly thinking about, and

the worst of it was that I was so frightened. It didnt matter how many locked

doors there were, I couldnt even feel protected here, so I was really afraid. . . .

Its like I just sat on a chair, and I remember I was thinking somebodys got

to come and help me now, because here I am completely paralyzed . . . com-

pletely unable to change my life . . . alone.

In Evas description of her fear, the repeated themes were solitude, immova-

bility and helplessness. These themes were often combined with each other; that

is, solitude and helplessness, immovability and helplessness. These themes were

related to her efforts to change her life; they were also expressed in terms of

lack, things that she misses, for example, the lack of other people, the lack of

movability, the lack of the opportunity to control. Together, they constitute an

obstacle to a good life.

Carolina gave a similar description of fear in her first interview. At the time,

she found herself in a very difficult situation. Her husband had found out where

she was through an acquaintance, and had threatened her. She was suffering from

a number of physical problems serious throat infections and stomach pains.

She said that she was terribly frightened. When I asked her to describe this feel-

ing, she stated that this was quite impossible, but proceeded to tell me about a

dream:

I have had the same dream for three nights now. It is the one with the pack of

dogs that tear me apart and I can see it and I wake up with this. I can still feel

the pain from when they tried to tear me into pieces. And then these wolves in

another dream tear me to pieces and I intend to go away and I cannot do any-

thing. I know that wolves work as a team to bring down their victim. I think this

has something to do with Adam [her former husband]; at the same time as I am

trying to hide I have these people around me not helping me but helping him

instead.

Solitude (the others are in the flock, while she is alone and excluded) is a theme

of Carolinas narrative as in Evas, as is the immovability (she intends to move,

but cant get away) and the helplessness (the wolves bite her, but she can do

nothing). The decisive difference is that Carolinas narrative tells of how a pack

of animals hunt her to kill her.

The last example of a description of the type of fear I have chosen to call

undifferentiated is an excerpt from Helens first interview. It is about a general

feeling of fear which is, however, not quite as comprehensive as the excerpts

from Eva and Carolina expressed. We are approaching the end of the interview.

Helen has told me how frightened she has been, and how upset she gets when she

thinks about it. She is very emotional when she says:

And at the same time as you try to do something about it, the fear kind of takes

over. I can look back and see how scared I was all the time, and how the fear

kept growing. Thats the biggest emotion I have, this fear, and you cant touch

it or see it. Its just there all the time, and its tough.

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 457

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 457

What Helen expressed in the process of describing her fear was that she is

re-evaluating her former life to some extent. As she looked back at her life she

found that she has always been afraid, and that her fear has increased.

Five to Ten Months after the Break-up

Differentiated fear is connected with the husband, is not completely overwhelm-

ing and is valued as possible to do something about. The second basic type of fear

I have chosen to call differentiated fear. It is primarily connected with one and

the same object, the husband. The women began to speak of this type of fear in

the second interview. This fear changed over time in such a way that the women

described an increasing capacity for action and reduced consequences on their

lives in general. Comparisons of the descriptions of fear in the third and sixth

interviews made this pattern apparent.

When the fear changes character and is related to the husband, other aspects

are also changed. The fear does not seem to be quite as dominating, and the

capacity for action is increased. In most of the descriptions of differentiated fear

which my informants gave me, the husband was the main object of fear. These

descriptions were set up in such a way that they did not primarily allow a

presentation of the narrators condition, but rather that of the person on whom the

fears were based, that is, the violent man. The following excerpt is from

Carolinas third interview, and can be compared with the quote from her first

interview:

Im still afraid of him. Like when I started on my new job, we changed our

clothes in the cellar. But I could only stand to change two or three times, and

then I couldnt be down there any more. I panicked; I had a real panic attack one

night when I worked late. I thought I was going to pass out. I was thinking,

What if I meet him down here? Where am I going to run to? Then I went to

talk to my boss. She knows whats happened to me, so she said, This wont

work, you should be able to change somewhere else. Ill find a room for you.

So it feels safe at work too, knowing that someone else knows.

The woman herself takes a double role in these narratives. She is both the

object of her terrible fear and, simultaneously, describes herself as being very

active in her attempts to fend off the danger. Whatever she does, though, she can

never feel secure, and describes her opportunities to affect the situation as being

very limited. A strong feeling of solitude is heard in the womens narratives. This

impression is based on the womans taking the acting subjects role as well as the

role of the frightened person whom the acting subject is trying to save and pro-

tect. In a few cases people who can help the woman appeared in the narratives,

but the overall pattern is one of solitude.

Some of the womens narratives differed from those of the majority, however,

in one important aspect: they were more self-scrutinizing, and contained more

thoughts about the individual and her actions during the time she was in the

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 458

458 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

relationship with the abusive husband. In this type of description, the women

claimed that they became afraid for themselves, when they looked back. The

following is an excerpt from Fredrikas fourth interview:

How could I have been so blind? Sometimes I feel almost afraid for myself. How

could he make me do that, how could I be so stupid? How could he manage to

do all that, how could I permit it? How did I get into that pattern? I fought it in

the beginning, but since I had such strong feelings about him, and felt that I had

a goal . . . I gave in.

The woman also seems quite alone in this type of description. In the last set of

interviews other people appear in some of the womens statements. Those women

who can break the pattern of solitude are also able to increase their capacities for

action. There is one important condition that the people with whom they make

contact for shorter or longer periods can support their active efforts.

After Two Years

Fear as a background emotion. The changes in the womens descriptions of

their fear, which took place between the first and second interviews, were con-

solidated during later interviews. The women spoke of fear as an emotion that

was still present to a great degree, but they referred to it in a somewhat different

way than they had in the first interview. The incapacity to act had disappeared,

and they felt that they had the opportunity to act to make themselves feel safer.

The extent of the fear was no longer such that it completely dominated their lives

as it had formerly done. It was no longer a question of overwhelming fear, but

rather of a background emotion which sometimes became activated.

Bea, the next-to-youngest of my informants, told me about such a develop-

ment. She had a young son who was fathered by the man who abused her. He

wanted to see the son often, and Beas fears were activated when these meetings

took place. In the final interview Bea stated that she was able to manage her fear

somewhat, and that her primary supporters were the police. She had received

good advice and support, as well as different kinds of protection from them.

During one period she carried an alarm kit; on other occasions police cars had

been directed to drive past Beas house on their way to the police station when

the husband was expected there. As the police said, That usually calms things

down a little. Bea stated that it worked well, and that the mere knowledge that

she was in close contact with the police did calm the husband.

In her final interview, Fredrika told me that she was still afraid of her former

boyfriend, of his unpredictability and of the fact that she had no control of where

he was, or whether he was going to take revenge. She had sought contact with

other women to get support, and she had a new and very friendly boyfriend. She

still avoided places where she might run into her former boyfriend. As the years

passed, her fear faded away.

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 459

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 459

Fear as a permanent companion. There was only one woman, Carolina, who

in the sixth interview immediately brought up the subject of fear as something

that marked her life. Her husband had continued to follow her around, and she

had had to move a couple of times. Two of her sons lived with their father, and

she could only meet them sporadically. The husband had communicated his view

through the sons that a mothers place is in the home. She had sought and

obtained a restraint on visitation but when the restraint was to be reviewed her

address was given to the husband. She got an unlisted telephone number which

was revealed when her telephone bill was erroneously sent to the husband.

Two other women, Eva and Isa, spoke of a feeling of general fear which was

activated when they thought of their husbands. Two years had gone by and

neither husband had been heard from. Isa had two children who were fathered by

her former husband. He had returned to his native country and kept in touch with

the children by mail. Even though neither Eva nor Isa had been threatened after

they left their husbands, they lived with fear that did not wholly dominate their

lives but was nevertheless always present. Both had considered this, and stated

that the feeling of fear had always been present, and was reinforced by the

husbands violent abuse. The following quotation comes from Isas sixth inter-

view. Toward the end of the interview, after Isa had brought up the subject of

fear, I posed the following question:

MH: This fear, is it something that has been an issue earlier in your life, or is

it something new?

Isa: No, its nothing new, no. I see the world around me as frightening any-

way, but this is so obviously what Im afraid of here. Otherwise its

more, well, it can be things like Im trying to get on a safe platform, live

in a place where theres not a lot of trouble. I guess I think that if its not

dangerous, at least its a little less frightening somehow. Theres a

pretty clear connection here . . . it comes from when I was growing up,

it was . . . you had to listen all the time for the tension. And my father

had a terrible temper that you always had to keep checking for.

In Isas case her position was complicated further by the fact that she admired

her father greatly, and felt that she was like him. She identified herself with

his intellectual interests, his ability to analyze logically and his ordered and con-

trolling sides. She valued that in herself, even though she had always been afraid

of him; he meant a great deal to her.

Break-up as an Act of Resistance

The most significant thing that I learned in my investigation was the fact that an

abused womans break-up is a process which is extended over at least a year, and

sometimes longer. Winning her freedom costs her suffering and struggling, while

the freedom is something she has never completely lost. This condition is basic,

and gives the woman motivation.

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 460

460 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

These insights have made me sceptical about theories of power struggles

between people claiming that the power relationships between people can be

described in terms of a binary structure in which the dominating are on one side

and the dominated on the other. Power is better described as something that is

omnipresent, and that can assume several different guises. One researcher who

has developed a power theory like this is Michel Foucault. In an interview

published under the title Power and Strategies (1980), he presents a discussion

of power and resistance, which he claims are closely intertwined:

There are no relations of power without resistances; the latter are all the more

real and effective because they are formed right at the point where relations of

power are exercised; resistance to power does not have to come from elsewhere

to be real, nor is it inexorably frustrated through being the compatriot of power.

It exists all the more by being in the same place as power; hence, like power,

resistance is multiple and can be integrated in global strategies (Foucault, 1980:

142).

Foucaults analysis of power relationships between people inspired me to

examine my interview material for how, when, where and in what way the resis-

tance of battered women can be expressed in the descriptions they gave me of the

progress of the break-up. Can it be true, I asked myself, that womens resistance

against the violence to which they were subjected is so ubiquitous that it is diffi-

cult to identify in the womans environment, and for the woman herself? One

researcher who would most probably give an affirmative answer to this question

is James C. Scott (1990). He claims that resistance is always present in dominated

people like slaves and bondsmen, but that they seldom dare to show their resis-

tance openly. Thus they may be presumed to accept the dominance of their

superiors. Beneath the surface, however, the dominated people create their own

space in which the resistance is expressed in a hidden transcript, which can be

represented in a more or less specific way.

When the woman leaves her husband, however, the resistance is expressed

clearly and openly. There is no longer any question of a hidden transcript. She

has fractured his sphere of dominance, and this is demonstrated publicly. The

violence no longer exists as a part of the relationship, nor is it still entirely an

issue between two private people. In the long run, this revelation can become an

issue between the husband and the state, in the form of the public prosecutor and

the judiciary. In an analysis of the power relationship between man and woman

solely in terms of dominance and subjugation, her action has a tendency to be

seen as a defeat, as a sign of surrender and the husbands ultimate victory. The

womans resistance and actions are hardly noticed at all in this kind of interpre-

tation. Throughout this article I have argued that the womans breaking up should

be interpreted as just that as an act of resistance.

Seeing a break-up as an act of resistance does, however, have its limitations.

The woman does something over which she has no control of the consequences.

She does not know whether her efforts will be rewarded with success, or whether

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 461

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 461

the husband will continue to pursue and abuse her. The basic reasons for the

womans fear stem from this insecurity.

In the case of my informants it seems that their efforts were rewarded with

success in the sense that they were not subjected to further violence with the

exceptions of Carolina, who was subjected to serious threats, and Gun and

Danielle, who pursued their husbands and were abused. After two years the

threats against Danielle still existed. Helen had been reunited with her husband.

The other women met their husbands very sporadically or not at all (see Table 3).

TABLE 3

The womens contact with their husbands after the break-up

Anja Met husband during trial. He was incarcerated. They never see each other.

Bea Met husband during trial. He was given a short prison sentence. They met in

connection with regular visitation of the child.

Carolina Threat. The husband came looking for her. She met him in connection with

the trial. He was given a short prison sentence and appealed against it.

Danielle After breaking up a second time, she met him in connection with the trial. He

was given a probational sentence. She met him sporadically after that, in

connection with visitation of the child.

Eva Met husband during trial. He was incarcerated. They never see each other.

Fredrika Never sees him.

Gun Never sees him.

Helen Reunited.

Isa Never sees him. He probably returned to his native country.

Jannike Never sees him. He probably returned to his native country.

Changing a Relationship by Breaking Up

A woman can, thus, succeed in her efforts to avoid the husbands violence by

breaking up, but not be successful in making him change his behaviour so that

their relationship can continue. The resistance of breaking up expresses, there-

fore, both the power she has and her powerlessness. Helen was the only one of

my informants who broke this pattern. When she left her husband she reported

him to the police, and he was arrested. While he was incarcerated he began to

re-evaluate crucial aspects of his life. He was never charged. He continued to

question himself and his actions. He had grown up with violence and unfair treat-

ment, and had simply continued in that pattern. Now he wanted to end all this,

reunite with Helen and the children, and start life anew. He sought help, and drew

up a barrier against his earlier life and his parents and succeeded. All of this

occurred outside Helens chance to influence or control. Her actions had, how-

ever, led to his making decisions about his life. These decisions later made a great

difference to the couples life together. He and Helen were reunited and had

another child together. The abuse was never repeated during the time I followed

up the family (almost four years).

An important characteristic of marital life is its profound link with the parties

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 462

462 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

individual life histories (Hydn, 1994). To end a violent relationship means to

end a personal involvement. When the battered woman leaves her husband, she

breaks the sphere of power that kept her in the relationship. At the same time,

however, she breaks the sphere of solidarity that is also a characteristic of the

marriage. I note that power and solidarity are in a paradoxical relation to each

other in violent marriages. The mans power over the woman is evident, but

if it was the only ingredient in a violent marriage, if the man was never that

repressive, if he never said anything but no, he could not compel the woman to

obey him, year after year. Power governs asymmetrical relationships where one

person is subordinated to the other; solidarity governs symmetrical relationships

characterized by social equality and similarity. The departing woman leaves both

relationships. Her wish to leave the violence may be as strong as her hesitation to

leave that which has been strong and positive in her life with the man. To resist

violence by separation could be costly for the woman since it may elicit anger in

the man, but also because she may lose something, which has been, or could have

been, positive.

Fear as Resistance

The closest readings to the womens descriptions of fear are to read them as

narratives about pain, which says something about the price of breaking up.

Alternatively, they can be read as narratives that have something to say about

womens desire and ability to resist. This reading is not completely self-evident.

We usually associate resistance with action. When we read the womens state-

ments as narratives that say something about womens resistance, then fear is an

expression of resistance not in that it includes action, but rather in that it consti-

tutes a power which makes the woman notice that what may happen is something

she doesnt want to see happen. The fear contains an unarticulated knowledge of

what she wants and doesnt want. She wants to avoid the undesirable and to attain

its opposite. She doesnt want her abusers lack of respect or his way of forcing

himself on her and attacking her body. She doesnt want his diminution of her

until she feels so little that she feels like an empty shell that can be invaded by

anyone, where any thoughts and feelings at all can be deposited. The fear

includes this type of unarticulated knowledge, which may be noticed in a con-

versation with the woman.

Fear, helplessness and resistance are closely associated with each other. I

believe that this close relation can be described thus: fear is the resistance offered

by those who are presumed to be powerless. The fact that the woman is

frightened means that she is opposed to violence, without necessarily having any

well-prepared strategy of how she can avoid being re-exposed. If the woman

receives help in articulating her fear, and is not influenced only by her own

powerlessness but can also confront her will to resist, then it is possible for her to

move on and act in accordance with this that is, to offer more active resistance.

To be frightened when one is subjected to violence is a reaction that is more or

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 463

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 463

less automatic. The abuser knows this. Fear is something he likes to evoke,

because it is easy to assume a dominant position over a frightened person with

little contact with her inner resistance. However, a frightened person in contact

with her inner resistance is not so easy to dominate. A person like that has the

possibility of acting to her own advantage.

When fear is protection. It was not fear of the husband that was the deciding

factor when the women in my study broke away. At some distance from the

violent marriage, this is something that surprises and sometimes frightens the

women. They think that it was only reasonable that they felt afraid and acted in

accordance with that feeling. We meet Eva again:

I dont remember being as afraid when we were together as I feel now that were

apart, except maybe for short periods. Perhaps I should have been.

My conclusion is that when the woman offered resistance to the violence in the

form of a break-up, her picture of the husband changed. This, in turn, led to her

seeing what she had been subjected to in a different way. The husband is now a

danger to her; she may have felt this earlier, but not at all in such a compulsive

way as now. Shortly after the break-up, the change in her way of seeing the

husband is expressed in an undifferentiated fear. Differentiated fear with the

husband as the object of the fear, which she feels at a later stage, can contain

everything from an image of him as omnipotent and omnipresent to a more

manageable feeling that his dangerousness is something that can be handled.

Both of these forms of fear lead to the woman protecting herself from the

husband. The fear thus also has a positive meaning in her life. This is worth

noting, especially since its negative influence is so obvious.

When no fear gives protection. In the second interview I found that three of

the women who spoke of their fears at the first meeting did not do so at the

second. They neither broached the subject spontaneously, nor did they bring it up

in the course of the conversation. It turned out later that these women were diffi-

cult to reach to make appointments for their third interviews. They had moved

without forwarding their telephone calls. I had to seek them through other women

to reestablish contact. It turned out that they had been in contact with their

husbands. They had actively avoided me, since they thought it was embarrassing

to admit that they had contacted the men. They were supposed to be taking part

in a project about break-ups!

During the third interview they gave different reasons for why they had seen

their husbands. Two women, Danielle and Helen, had been present when the

husband was there to meet the children, in order to supervise the meeting and pro-

tect the children. The meetings had been positive, and had awakened hopes that

possibly they could continue their lives together. Both women had, however,

been seriously abused again.

The third woman, Gun, went to the husbands home with the intention of

making an agreement, to once and for all end the relationship. She had tried to

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 464

464 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

end it several times earlier, but had always gone back to him because she

didnt want to separate without a proper conclusion. She sought some form

of reinforcement from the husbands side. It didnt necessarily need to be an

apology, but rather a confirmation that they had both experienced the same thing,

and that he was sorry that she had had to suffer so much. Over the years he had

been completely unsympathetic, which Gun had felt was belittling and degrading.

It did not work out as she had hoped, either. Here is a section five minutes into

her third interview:

Gun: I went there twice, and then he came in.

MH: Did you leave then or stay for a while?

Gun: No, not a while, Id been there for a few hours when I saw him there. I

got mad and I felt that this was my home, and there sits that idiot.

MH: Did you begin to scold him or . . .?

Gun: Yes. Ive got so much anger; theres so much I want to say. Its like a

treadmill. I say things like You damned dope addict. I know Im really

mean, and Im probably pretty provoking in a way, but what Im thinking

is, I have the right to say this!

It is probable that the husband did not share her viewpoint on what she had a

right to say. Gun got a different confirmation from the one she was so anxiously

seeking. When she was alone with him she had difficulty protecting herself. He

abused her badly. In the third interview Gun told about her strong fear of the

husband. When she went to see him her fear was overpowered by her anger and

by the thought of getting him to act as she wished. Now she had completely

changed her mind. She could still get angry when she thought of him, but

mostly she was afraid. She realized that she had hardly any chance of influencing

him, and she did not believe in the possibility of a change. He was a severely dis-

turbed psychopath, she said, a drug abuser who was completely out of control,

and a victim of a twisted libido. She resolved never to contact him again, and

finally managed to end the relationship mentally without his reinforcement.

ENTERING THE WORLD OF THE FEARFUL

Implications for Feminist and Psychological Practice

Why doesnt she leave? I criticized this question in my introduction, because it

is based on the erroneous supposition that a battered woman really does stay. In

conclusion, I can add that it is based on yet another erroneous supposition, which

assumes that the break-up consists of one single event. It does not. It consists of

a process, which extends over several years, one which involves risks to the

woman. The most obvious risk is associated with the womans limited resources

of controlling what happens during the process of breaking up. She has offered

resistance and fractured the husbands sphere of power without having control of

the consequences that the break-up can bring about. She has failed in what she

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:11 am Page 465

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 465

may have wished most to get the husband to change his behaviour. This lack of

the opportunity to influence and control constitutes one of the basic reasons for

the womans fear during the entire break-up.

Fear constitutes both a positive and a negative power during the process of

breaking up. It acts negatively because it is painful, requires energy and involves

risks to the woman. Undifferentiated fear means a greater risk because it seems

to be expressed physically to a great extent. If the woman is not able to express

it in words or actions, it can encapsulate itself, with psychosomatic symptoms as

a result. Fear of the husband can also occupy so much of the womans strength

for so long a time that her opportunities of going on with her life are seriously

limited.

On the other hand, fear constitutes a positive power for action because it bears

a message to the woman that danger threatens, and that what might happen is

something she does not want to have happen. It is not certain that the woman can

identify this message and properly evaluate it. She may need to have it explained.

The womans fear communicates a strong message. It is a signal to the world

around that contact is desired, and a response must be forthcoming in order for

development to continue being positive.

In making an extended study of abused womens narratives about breaking up,

and finding fear to be such a central theme, it becomes evident that the woman

must be able to deal with her fear in order to be able to go on with her life. It is

equally evident that this is not something she can do on her own. She needs

concrete assistance and different forms of protection. This protection should be

designed so that it limits her freedom as little as possible, but does limit his

freedom. Most of the measures of protection available today for example, pro-

tected living in a womens shelter, alarm kit, new identity and unlisted address

limit her freedom, not his. I believe that changes should be made in societys

measures to limit his freedom, for the purpose of getting him to leave the woman

alone. However, it would be extending the boundaries of this article too far if I

were to discuss how these measures could be designed.

What does fall within the framework of the article, though, is another aspect of

the fact that the woman needs help in dealing with her fear she needs to com-

municate it. In order to make her fear manageable, she must find a listener/

respondent with whom she can formulate her experiences. It is not necessarily

clear or easy to find a listener, because her fear is unique in many ways; it is not

shared by many others and is therefore difficult to explain. I would like to con-

clude this article with an analysis of the fear inherent to the break-up, bringing

out some themes that can be valuable to those whose job involves listening to

fearful abused women who have left their husbands.

To not recognize oneself. Generally, it is difficult for the fearful to find a

listener/respondent, since the kind of fear she experiences is unknown to most

people. Fear itself is well known to each of us. Everyone is afraid many times in

his/her life. A fearful woman thus shares this experience with others, meaning

that her experiences are not unfamiliar or incomprehensible. Those around

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:12 am Page 466

466 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

her are able to recognize this fear. The experience of fear as a shared human

experience, however, is related to temporary, acute fear that is associated with a

special and time-limited event (when that big dog started growling and showing

his teeth, I was really scared). With regard to long-lasting, almost chronic, fear,

the circumstances are different. This type of experience is not an experience that

is shared by most people. Situations which lead to people living in a state of

chronic fear include living in a war zone or under threats and violence for months

or years. These defining features of chronic fear cause difficulties for the

chronically afraid person. They make it hard for her to communicate her feelings

to others. A chasm grows between her reality and that of others. The others have

not experienced the danger-filled situation or met the person she is afraid of. How

can they know what the situation really is? How can they know whether hes

really as dangerous as she thinks? Perhaps when they met him, he was as nice as

anyone could be. How can others know whether she is exaggerating or not, when

they have not seen it with their own eyes? Or imagined that he is even more

dangerous than she thinks? There is only one person who has been present with

the woman during the battering situation, only one person who knows what it has

been like the man who has been beating her. My informants related how

they had insistently sought verification from their husbands of what they had

experienced or felt during the course of their marriage.

The language of fear. When women describe undifferentiated fear in their first

interview, several images reappear. It is the same kind of condition that is

described the immovable and unprotected. It is the girl who sits on a chair,

unprotected, paralyzed and incapable of moving. It is the girl who is torn to

shreds by hunting wolves. In these cases the fear defies words and expresses

itself instead in muteness and paralysis. This physical expression can have a

communicable meaning: protect me, make my life better! But this wish is not

easy for the world to interpret.

Each time the womans fear is lifted out of its physical expression and

verbalized there is also a risk that it will be re-encapsulated. The attempt to

convey the feeling can fail, so that further attempts seem to be fruitless. Since the

verbal signs are so unstable, the listener cannot simply adopt a passive role, but

must ask actively. As if this were not difficult enough, the fragile verbalization

can be used for a special purpose; the woman who is frightened can avoid speak-

ing about it in order to hide her fear from herself. If this is her primary strategy,

her silence can make a transition from being a time-limited condition to some-

thing that is seen by those around her as a part of her character. It is not the fear

itself that does this, but rather the way in which the woman handles her fear.

There is an example of this in Guns first interview, where she describes how she

freezes everything. She states that she has become an expert at freezing situa-

tions and putting herself into a condition of total apathy as she avoids all

thoughts and feelings. This has had the negative result that the world around her

has no comprehension of the suffering she has endured she seems so cool and

seems to have everything under control.

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:12 am Page 467

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 467

In order to go on with her life, it is necessary for the woman to place herself in

the narrative and assign herself the position of subject. In order to help her in this

process, it is important to meet her both in her feelings of solitude and resigna-

tion and in her capacity for action. When she met the man who would later abuse

her, she was on her way somewhere, and came from somewhere. She needs help

in recalling this, and in finding herself again. Living in a relationship where one

is battered is so all-consuming that it can threaten to become the womans whole

identity. But a woman who has been abused by her husband is not a battered

woman. She is a woman who has experienced living with a husband who beat

her. There is a great difference. Violence is not the only defining factor in her life.

In order for clinicians to work more effectively with abused women, it is

necessary to develop strategies aimed at helping women to avoid adopting an

identity as a battered woman. Many women try to do that on their own, by deny-

ing the violence, by keeping it a secret, or by becoming experts on freezing

situations. The problem is that the identity as a battered woman, as well as the

various strategies to avoid that identity, offer a too-limited base on which to build

a self-understanding. In the same way, understanding oneself as a survivor (an

understanding that emanates from the man and his violent behaviour), has the

same effect. What the woman needs help to do, is to define herself as the woman

of experience she really is. She has encountered a dark side of female experience

that she shares with other women, in the present as well as in historical times. To

be able to define her in that direction, her story of what she has experienced must

contain more than an account of male dominance and female subordination. This

does not mean that her pain and difficulties should be belittled. It means that in

addition to each story of male violent behaviour there is a parallel story of female

opposition. It means that the history of pain and forced subordination in her life

is accompanied by the history of resistance. These two stories constitute parts of

the abused womans history and both need to be acknowledged.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The research reported in this article was supported by a grant from the Swedish

Council of Research. I would like to thank Judith L. Herman, Harvard Medical

School, Mary R. Harvey and Priscilla Dass, both at Cambridge Hospital,

Cambridge, MA, and Jane M. Liebschutz, Boston University, for reading an

earlier draft of this paper and making several thoughtful comments. My acknow-

ledgement also goes to the anonymous reviewers for making comments that

helped me shape my thinking.

NOTES

1. Some of the women in this category had immigrated to Sweden with their husbands,

and had residence permits. Most of them had stayed home and taken care of their

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:12 am Page 468

468 Feminism & Psychology 9(4)

families, and had few or no ties to the Swedish labour market. Another group consisted

of refugee women who had left their husbands before the decision on their right to stay

in Sweden was made. Another group of women with non-Nordic origins had been

married to Swedish men whom they had left, or had been left before they received stay-

ing permits (Ansvarsgruppens verksamhetsberttelse fr kvinnohuset 19931997).

These different categories of women were united in that they were subjected to abuse

by their husbands. Otherwise they lived under such widely dissimilar conditions that

different investigations would have been required to examine their situations.

2. One researcher who has worked in the opposite direction is the American feminist and

psychologist Leonore Walker (1984). In order to give women a place in psychiatry,

Walker constructed a special woman a woman characterized by suffering from

Battered Woman Syndrome (BWS). BWS includes cognitive disturbances such as con-

fusion, absent-mindedness, lack of concentration, faulty memory, a markedly retiring

disposition and depression (Walker, 1994).

REFERENCES

Bowker, L.H. (1993) A Battered Womans Problems are Social, Not Psychological, pp.

15465 in R. Gelles and D. Loseke (eds) Current Controversies on Family Violence.

Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Eliasson, M. (1997) Mns vld mot kvinnor: En kunskapsversikt om kvinnomisshandel

och vldtkt, dominans och kontroll. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur.

Foucault, M. (1980) Power and Strategies, pp. 13445 in C. Gordon (eds) Power/

Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 19721977 by Michel Foucault.

London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Gelles, R. (1979) Family Violence. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Herman, J. (1992) Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic

Abuse to Political Terror. New York: Basic Books.

Hydn, M. (1994) Woman Battering as Marital Act: The Construction of a Violent

Marriage. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

Hydn, M. (1995a) Kvinnomisshandel inom ktenskapet. Stockholm: Liber.

Hydn, M. (1995b) Verbal Aggression as Pre-History of Woman Battering, Journal of

Family Violence 10(1): 5572.

Hydn, M. and McCarthy, I. (1994) Woman Battering and FatherDaughter Incest

Disclosure: Conversations of Denial and Acknowledgement, Discourse and Society

5(4): 54365.

Kelly, L. (1988) Surviving Sexual Violence. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lundgren, E. (1993) Det fr da vaere grenser for kjnn: Voldelig empiri og feministisk

teori. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Miller, D. (1994) Women Who Hurt Themselves: A Book of Hope and Understanding.

New York: Basic Books.

Mullender, A. (1996) Rethinking Domestic Violence: The Social Work and Probation

Response. London: Routledge.

Pahl, J., ed. (1985) Private Violence and Public Policy: The Needs of Battered Women and

the Response of the Public Services. London: Routledge.

Scott, J.C. (1990) Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New

Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press.

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

04_Hyden article 13/10/99 10:12 am Page 469

HYDN: The World of the Fearful 469

Straus, M. and Gelles, R. (1990) Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors

and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. New Brunswick, NJ and London:

Transaction Publishers.

Wade, A. (1997) Small Acts of Living: Everyday Resistance to Violence and Other

Forms of Oppression, Contemporary Family Therapy 19(1): 2339.

Waites, E. (1993) Trauma and Survival: Post-Traumatic and Dissociative Disorders in

Women. New York: W.W. Norton.

Walker, L. (1984) Battered Woman Syndrome. New York: Springer.

Walker, L. (1994) Abused Women and Survivor Therapy. Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association.

Margareta HYDN is Associate Professor at the Department of Social Work,

Stockholm University, Sweden, and a psychotherapist in private practice. Her

research interests are in the field of violence against women, family studies and

narrative studies.

ADDRESS: Department of Social Work, Stockholm University, 106 91

Stockholm, Sweden.

[email: Margareta.Hyden@socarb.su.se]

Downloaded from fap.sagepub.com at University Library Utrecht on July 8, 2016

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Connectu, Inc. v. Facebook, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 176Документ4 страницыConnectu, Inc. v. Facebook, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 176Justia.comОценок пока нет

- Open Fire Assembly GuidesДокумент2 страницыOpen Fire Assembly GuidesRandall CaseОценок пока нет

- FO B1 Commission Meeting 4-10-03 FDR - Tab 7 - Tobin Resume - Yoel Tobin 579Документ1 страницаFO B1 Commission Meeting 4-10-03 FDR - Tab 7 - Tobin Resume - Yoel Tobin 5799/11 Document ArchiveОценок пока нет

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitДокумент80 страницUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Tamil Nadu Government Gazette: ExtraordinaryДокумент2 страницыTamil Nadu Government Gazette: ExtraordinaryAnushya RamakrishnaОценок пока нет

- Case Facts Issues and RatioДокумент12 страницCase Facts Issues and RatioKio Paulo Hernandez SanAndresОценок пока нет

- Holocaust Era Assets Conference Proceedings 2009Документ653 страницыHolocaust Era Assets Conference Proceedings 2009bekowiczОценок пока нет

- Prohibitory Orders: Nature Creation Duration Power To Amend CaveatДокумент1 страницаProhibitory Orders: Nature Creation Duration Power To Amend CaveatSarannRajSomasakaranОценок пока нет

- Sandy City Huish Investigation Report (Redacted)Документ24 страницыSandy City Huish Investigation Report (Redacted)The Salt Lake Tribune100% (1)

- ASIL Public International Law Bar Reviewer 2019 PDFДокумент73 страницыASIL Public International Law Bar Reviewer 2019 PDFVM50% (2)

- Usurpation of Real RightsДокумент7 страницUsurpation of Real RightsTukneОценок пока нет

- Derek Jarvis v. Analytical Laboratory Services, 3rd Cir. (2012)Документ6 страницDerek Jarvis v. Analytical Laboratory Services, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Prisoner of Zenda - Elements of The NovelДокумент16 страницPrisoner of Zenda - Elements of The NovelNor Azizah Bachok100% (5)

- Tarikh Besday 2023Документ4 страницыTarikh Besday 2023Wan Firdaus Wan IdrisОценок пока нет

- Part 2Документ253 страницыPart 2Fairyssa Bianca SagotОценок пока нет

- A Meeting in The Dark - Ngugu Wa Thiong'oДокумент1 страницаA Meeting in The Dark - Ngugu Wa Thiong'oChristian Lee0% (1)

- New DissertationДокумент105 страницNew Dissertationkuldeep_chand10100% (3)

- JQC Complaint No. No 12385 Judge Claudia Rickert IsomДокумент165 страницJQC Complaint No. No 12385 Judge Claudia Rickert IsomNeil GillespieОценок пока нет

- Operating Room Nursing: S Y 2018-2019 FIRST SEMДокумент29 страницOperating Room Nursing: S Y 2018-2019 FIRST SEMMaria Sheila BelzaОценок пока нет

- Criminal Bigamy PresentationДокумент9 страницCriminal Bigamy PresentationA random humanОценок пока нет

- 4 G.R. No. 171673 Banahaw vs. PacanaДокумент8 страниц4 G.R. No. 171673 Banahaw vs. Pacanaaags_06Оценок пока нет

- Towing Ship Inspection ChecklistДокумент1 страницаTowing Ship Inspection ChecklistdnmuleОценок пока нет

- 3.07.2.13-2.2b Levitsky&Way 2003Документ68 страниц3.07.2.13-2.2b Levitsky&Way 2003Leandro Hosbalikciyan Di LevaОценок пока нет

- Raul Guerra Fdle ReportДокумент84 страницыRaul Guerra Fdle Reportal_crespo_2Оценок пока нет

- Nisce vs. Equitable PCI Bank, Inc.Документ30 страницNisce vs. Equitable PCI Bank, Inc.Lj Anne PacpacoОценок пока нет

- 1st Test QAДокумент19 страниц1st Test QAKiran AmateОценок пока нет

- Immunizations MeningococcalДокумент2 страницыImmunizations MeningococcalVarun ArvindОценок пока нет

- When Grizzlies Walked UprightДокумент3 страницыWhen Grizzlies Walked Uprightleah_m_ferrillОценок пока нет

- Complainant/s,: Office of The City Prosecutor Nelson AlarconДокумент5 страницComplainant/s,: Office of The City Prosecutor Nelson AlarconLeyОценок пока нет

- Class XII English CORE Chapter 5 - Indigo by Louis FischerДокумент15 страницClass XII English CORE Chapter 5 - Indigo by Louis FischerShivam YadavОценок пока нет