Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Writing

Загружено:

Hiroshi Carlos0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

5 просмотров12 страницnew

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документnew

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

5 просмотров12 страницWriting

Загружено:

Hiroshi Carlosnew

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 12

VOLUNTARINESS Concurrence of

freedom, intelligence and intent makes up the

criminal mind behind the criminal act. Thus,

to constitute a crime, the act must, generally and

in most cases, be accompanied by a criminal intent.

Actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea. No crime

is committed if the mind of the person performing

the act complained of is innocent (People vs.

Ojeda, G.R. Nos. 104238-58, June 3, 2004).

Voluntariness is an element of crime, whether

committed by dolo or culpa or punishable under

special law. The act to be considered a crime must

be committed with freedom and intelligence. In

addition to voluntariness, intentional felony must

be committed with dolo (malice), culpable felony

with culpa, and mala prohibita under special law

with intent to perpetrate the act or with specific

intent (such as animus possidendi in illegal

possession of firearm). Presumption of

voluntariness: In the determination of the

culpability of every criminal actor, voluntariness

is an essential element. Without it, the

imputation of criminal responsibility and the

imposition of the corresponding penalty cannot be

legally sanctioned. The human mind is an entity,

and understanding it is not purely an intellectual

process but is dependent to a large degree upon

emotional and psychological appreciation. A

mans act is presumed voluntary. It is improper to

assume the contrary, i.e. that acts were done

unconsciously, for the moral and legal

presumption is that every person is presumed to be

of sound mind, or that freedom and intelligence

constitute the normal condition of a person

(People vs. Opuran, G.R. Nos. 147674-75,

March 17, 2004).

CRIMINAL INTENT To be held

liable for intentional felony, the offender must

commit the act prohibited by RPC with specific

criminal intent and general criminal intent.

General criminal intent (dolo in Article 3 of

RPC) is an element of all crimes but malice is

properly applied only to deliberate acts done on

purpose and with design. Evil intent must unite

with an unlawful act for there to be a felony. A

deliberate and unlawful act gives rise to a

presumption of malice by intent. On the other

hand, specific intent is a definite and actual

purpose to accomplish some particular thing. In

estafa, the specific intent is to defraud, in

homicide intent to kill, in theft intent to gain

(Recuerdo vs. People, G.R. No. 168217, June

27, 2006, ). In the US vs. Ah Chong, the

accused was acquitted because of mistake of fact

principle even though the evidence showed that he

attacked the deceased with intent to kill (United

States vs. Apego, G.R. No. 7929, November 8,

1912; Dissenting opinion of J. Trent), which

was established by the statement of the accused

"If you enter the room I will kill you." Article

249 (homicide) should be read in relation to

Article 3. The accused was acquitted not because

of the absence of intent to kill (specific intent)

but by reason of lack of general intent (dolo or

malice).

PRESUMED MALICE - The general

criminal intent (malice) is presumed from the

criminal act and in the absence of any general

intent is relied upon as a defense, such absence

must be proved by the accused (Ah Chong case,

the accused was able to rebut the presumption of

general criminal intent or malice). Generally, a

specific intent is not presumed. Its existence, as a

matter of fact, must be proved by the State just as

any other essential element. This may be shown,

however, by the nature of the act, the

circumstances under which it was committed, the

means employed and the motive of the accused

(Recuerdo vs. People, G.R. No. 168217, June

27, 2006). There are other specific intents that

are presumed. If a person died due to violence,

intent to kill is conclusively presumed. Intent to

gain is presumed from taking property without

consent of owner.

MOTIVE

Doubt as to the identity of the culprit -

Motive gains importance only when the identity of

the assailant is in doubt. As held in a long line of

cases, the prosecution does not need to prove the

motive of the accused when the latter has been

identified as the author of the crime. The accused

was positively identified by witnesses. Thus, the

prosecution did not have to identify and prove the

motive for the killing. It is a matter of judicial

knowledge that persons have been killed for no

apparent reason at all, and that friendship or even

relationship is no deterrent to the commission of a

crime. The lack or absence of motive for

committing the crime does not preclude conviction

where there are reliable witnesses who fully and

satisfactorily identified the petitioner as the

perpetrator of the felony (Kummer vs. People, GR

No. 174461, September 11, 2013).

Circumstantial or inconclusive evidence -

Indeed, motive becomes material when the evidence

is circumstantial or inconclusive, and there is some

doubt on whether a crime has been committed or

whether the accused has committed it. The

following circumstantial evidence is sufficient to

convict accused: 1. Accused had motive to kill the

deceased because during the altercation the latter

slapped and hit him with a bamboo, prompting

Romulo to get mad at the deceased; 2. Accused

was chased by the deceased eastward after the

slapping and hitting incident; 3. Said accused

was the last person seen with the deceased just

before he died; (4) Accused and Antonio Trinidad

surrendered to police authorities with the samurai;

(5) Some of the wounds inflicted on the deceased

were caused by a bolo or a knife. (Trinidad vs.

People, GR No. 192241, June 13, 2012).

INDETERMINATE OFFENSE

DOCTRINE In People vs. Lamahang,

G.R. No. 43530, August 3, 1935, En Banc -

Accused who was caught in the act of making an

opening with an iron bar on the wall of a store

was held guilty of attempted trespassing and not

attempted robbery. The act of making an opening

on the wall of the store is an overt act of

trespassing since it reveals an evident intention to

enter by means of force said store against the will

of its owner. However, it is not an overt act of

robbery since the intention of the accused once he

succeeded in entering the store is not determinate;

it is subject to different interpretations. His final

objective could be to rob, to cause physical injury

to its occupants, or to commit any other offense.

In sum, the crime the he intended to commit inside

the store is indeterminate, and thus, an attempt to

commit it is not punishable as attempted felony.

In Cruz vs. People, G.R. No. 166441,

October 08, 2014 - The petitioner climbed on top

of the naked victim, and was already touching her

genitalia with his hands and mashing her breasts

when she freed herself from his clutches and

effectively ended his designs on her. Yet, inferring

from such circumstances that rape, and no other,

was his intended felony would be highly

unwarranted. This was so, despite his lust for and

lewd designs towards her being fully manifest.

Such circumstances remained equivocal, or

"susceptible of double interpretation" (People v.

Lamahang). Verily, his felony would not

exclusively be rape had he been allowed by her to

continue, and to have sexual congress with her, for

some other felony like simple seduction (if he

should employ deceit to have her yield to him)

could also be ultimate felony.

PROXIMATE CAUSE

Proximate cause is the primary or moving

cause of the death of the victim; it is the cause,

which in the natural and continuous sequence

unbroken with any efficient intervening cause

produces death and without which the fatal result

could not have happened. It is the cause, which is

the nearest in the order of responsible causation

(Blacks Law Dictionary). Intervening cause -

The direct relation between the intentional felony

and death may be broken by efficient intervening

cause or an active force which is either a distinct

act or fact absolutely foreign from the felonious

act of the offender. Lightning that kills the

injured victim or tetanus infecting the victim

several days after the infliction of injuries, or

voluntary immersing the wounds to aggravate the

crime committed by accused is an intervening

cause. Thus, the accused is liable for physical

injuries because of the intervening cause rule. On

the other hand, carelessness of the victim, or

involuntary removal of the drainage, lack of

proper treatment is not an intervening cause.

Hence, the accused is liable for the death because

of the proximate cause rule.

If the victim died due to tetanus of which he

was infected when the accused inflicted injuries

upon him, the crime committed is homicide (People

vs. Cornel, G.R. No. L-204, May 16, 1947).

If the victim died due to tetanus of which he was

infected after the accused inflicted injuries upon

him, the crime committed is physical injuries. The

accused is not liable for homicide because tetanus

is an efficient intervening cause. Thus, the

proximate cause of the death of the victim is not

the infliction of injuries. In Villacorta vs.

People, G.R. No. 186412, September 7, 2011

(Justice De Castro), there had been an interval of

22 days between the date of the stabbing and the

date when victim was rushed to hospital, exhibiting

symptoms of severe tetanus infection. Since the

victim was infected of severe tetanus, he died the

next day. The incubation period of severe tetanus

is less than 14 days. Hence, he could not have

been infected at the time of the stabbing since that

incident occurred 22 days before the victim was

rushed to the hospital. The infection of victims

stab wound by tetanus was an efficient

intervening cause. The accused was held liable for

physical injuries.

Proximate cause has been defined as "that

cause, which, in natural and continuous sequence,

unbroken by any efficient intervening cause,

produces the injury, and without which the result

would not have occurred." Although there was no

direct injury on his vital organs of the victim, his

wounds affected his kidneys, causing multiple

organ failure and eventually his death. Accused is

liable for homicide. Without the stab wounds, the

victim could not have been afflicted with an

infection which later on caused multiple organ

failure that caused his death. The offender is

criminally liable for the death of the victim if his

delictual act caused, accelerated or contributed to

the death of the victim (Belbis, Jr. vs. People,

GR No. 181052, November 14, 2012).

Вам также может понравиться

- Sps Buffe Vs Sec GonzalesДокумент1 страницаSps Buffe Vs Sec GonzalesHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Buenaflor Car Services Vs DavidДокумент1 страницаBuenaflor Car Services Vs DavidHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Material Master-Approval ProcessДокумент7 страницMaterial Master-Approval ProcessHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Espina vs. Zamora, Jr. Digest (2010)Документ3 страницыEspina vs. Zamora, Jr. Digest (2010)Hiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- 02 Sison Vs Board of AccountancyДокумент3 страницы02 Sison Vs Board of AccountancyHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Sps Villuga Et Al Vs KellyДокумент5 страницSps Villuga Et Al Vs KellyHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- 11 The Holy See Vs Rosario Jr.Документ2 страницы11 The Holy See Vs Rosario Jr.Hiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- 13 People V Hayag DigestedДокумент1 страница13 People V Hayag DigestedHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Banco Do Brasil Vs CAДокумент2 страницыBanco Do Brasil Vs CAHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- Fortunata Vs CAДокумент4 страницыFortunata Vs CAHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Banares Vs BalisingДокумент5 страницBanares Vs BalisingHiroshi Carlos100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Abangan v. Abangan 40 Phil.477 (1919)Документ1 страницаAbangan v. Abangan 40 Phil.477 (1919)Hiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

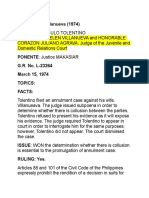

- 03 Tolentino Vs VillanuevaДокумент2 страницы03 Tolentino Vs VillanuevaHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- 64 Interpacific Transit v. AvilesДокумент4 страницы64 Interpacific Transit v. AvilesHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- People Vs TandoyДокумент2 страницыPeople Vs TandoyHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- 36 Lucas Vs Lucas-DIGESTEDДокумент2 страницы36 Lucas Vs Lucas-DIGESTEDHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- People Vs Napat-AДокумент4 страницыPeople Vs Napat-AHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- Nollora Jr. Vs PeopleДокумент2 страницыNollora Jr. Vs PeopleHiroshi CarlosОценок пока нет

- LAW203 - Yu Ming Jin - Prof Maartje de VisserДокумент55 страницLAW203 - Yu Ming Jin - Prof Maartje de VisserLEE KERNОценок пока нет

- Aadhaar Update Form: Aadhaar Enrolment Is Free & VoluntaryДокумент4 страницыAadhaar Update Form: Aadhaar Enrolment Is Free & VoluntarySushant YadavОценок пока нет

- Future European Refining Industry June2012 PDFДокумент23 страницыFuture European Refining Industry June2012 PDFdiego.lopez1870Оценок пока нет

- Rockland Construction v. Mid-Pasig Land, G.R. No. 164587, February 4, 2008Документ4 страницыRockland Construction v. Mid-Pasig Land, G.R. No. 164587, February 4, 2008Charmila Siplon100% (1)

- Updated Espoir - Commenter AggreementДокумент7 страницUpdated Espoir - Commenter AggreementRegine Rave Ria IgnacioОценок пока нет

- Syllabus For Civil Procedure Atty. Victor Y. Eleazar: Rule 16 To 36Документ8 страницSyllabus For Civil Procedure Atty. Victor Y. Eleazar: Rule 16 To 36Agnes GamboaОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Reviewer Claim and Adjustment LettersДокумент3 страницыReviewer Claim and Adjustment LettersJeck Remar MandasОценок пока нет

- AIR 1967 SC 1895devi Das Gopal Krishnan and Ors. v. State of Punjab and Ors.Документ14 страницAIR 1967 SC 1895devi Das Gopal Krishnan and Ors. v. State of Punjab and Ors.Harsh GargОценок пока нет

- Court-Presentment of EvidenceДокумент2 страницыCourt-Presentment of EvidenceMichael KovachОценок пока нет

- OM ZSE40A-IsE40A OMM0007EN-G Dig Pressure SwitchДокумент76 страницOM ZSE40A-IsE40A OMM0007EN-G Dig Pressure SwitchcristiОценок пока нет

- Steward v. West - Order On Motion Dismissing Most of ClaimsДокумент22 страницыSteward v. West - Order On Motion Dismissing Most of ClaimsMark JaffeОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Duff v. Prison Health Services, Inc. Et Al (INMATE2) - Document No. 5Документ6 страницDuff v. Prison Health Services, Inc. Et Al (INMATE2) - Document No. 5Justia.comОценок пока нет

- TAX Tax Law 2Документ158 страницTAX Tax Law 2iamtikalonОценок пока нет

- CfbrickellapplicationДокумент84 страницыCfbrickellapplicationNone None None0% (1)

- Chapter 3. System of Absolute Community Section 1. General Provisions Section 2. What Constitutes Community PropertyДокумент6 страницChapter 3. System of Absolute Community Section 1. General Provisions Section 2. What Constitutes Community PropertyGenevieve TersolОценок пока нет

- Vishal Jeet v. UOI (1990)Документ6 страницVishal Jeet v. UOI (1990)Vinati ShahОценок пока нет

- Assured Shorthold Tenancy Agreement: CBBJJFGJJJHHHGGДокумент5 страницAssured Shorthold Tenancy Agreement: CBBJJFGJJJHHHGGJan TanaseОценок пока нет

- Customary Law of Italy Comparative World HistoryДокумент11 страницCustomary Law of Italy Comparative World HistorySaurin ThakkarОценок пока нет

- Vishwesha Kumara.1FF Player Voice - Part-Time - Contractor Employment Agreement - 1FFДокумент12 страницVishwesha Kumara.1FF Player Voice - Part-Time - Contractor Employment Agreement - 1FFdcfl k sesaОценок пока нет

- Discovery SentencingДокумент40 страницDiscovery SentencingForeclosure Fraud100% (2)

- Barco v. CA, G.R. 120587, 20 January 2004Документ3 страницыBarco v. CA, G.R. 120587, 20 January 2004Deyo Dexter GuillermoОценок пока нет

- Diane P Wood Financial Disclosure Report For 2009Документ9 страницDiane P Wood Financial Disclosure Report For 2009Judicial Watch, Inc.Оценок пока нет

- BylawsДокумент4 страницыBylawsPallavi Dalal-Waghmare100% (1)

- Legal Metrology Act, 2009Документ10 страницLegal Metrology Act, 2009prakharОценок пока нет

- Intro To Criminology Notes For Board ExamsДокумент3 страницыIntro To Criminology Notes For Board ExamsAllen Tadena100% (1)

- FZCO - Jebel Ali Regulations PDFДокумент13 страницFZCO - Jebel Ali Regulations PDFseshuv2Оценок пока нет

- G. Election Offenses Prosecution of Election Offenses: Section 1Документ15 страницG. Election Offenses Prosecution of Election Offenses: Section 1Threes SeeОценок пока нет

- Barking Dog OrdinanceДокумент5 страницBarking Dog OrdinancePaul ReillyОценок пока нет

- Broken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.От EverandBroken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (45)

- If You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodОт EverandIf You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (1804)