Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Dificultades en Escritura

Загружено:

Tio Alf EugenioИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Dificultades en Escritura

Загружено:

Tio Alf EugenioАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Occupational Therapy for Children with

Handwriting Difficulties: A Framework for

Evaluation and Treatment

SidneyChu

H andwrltln. Is one of the most complex skills that Is learnt and taught. It requires motor, sensory,

perceptual, praxis and cognitive functions, and the Integration of these functions. When the com-

plex nature of this skill is considered, it comes as little surprise that many children experience diffi-

culty in mastering this area.

When an occupational therapist observes that a child referred to the service is having difficulty

with handwriting, It becomes necessary for the therapist to administer procedures to Identify the

strengths and weaknesses that will then become the basis for a remedial programme.

This article presents a conceptual framework for evaluating and treating handwriting difficulties

presentidby children In mainstream education with specific developmental disorder, such as dys-

praxia .or dyslexia. The performance components and functional performance of handwriting are

briefly reviewed. Both evaluation and Intervention procedures are discussed In order to guide the

therapist in developing remedial and Instructional programmes. The article highlights the unique

role oft,", .occupatlonal therapist In evaluating and treating a child's functional performance of

handwriting skillS.

Introduction explanation of the handwriting process has been articulated, it

is possible to identify preliminary theoretical arguments con-

Learning to write legibly is a major occupation of childhood

cerning functions and dysfunctions.

(Cunningham, 1992). This intricate and complex process is

one of the child's first tasks in an academic setting.

Frequently, children who need to pay considerable attention to Functions of handwriting

the mechanical requirements of writing have difficulty with Writing is an efficient way to record information and events. It

other higher-order learning processes, such as dictation or serves as a tool for communication as well as a means to pro-

story writing, reading, spelling, comprehension, mathematics ject feelings, thoughts and ideas. Hagin (1983) stressed that

and other academic learning. handwriting is the usual medium by which pupils convey to

Problems with handwriting are one of the most common their teachers the progress that they have made in learning

reasons for referring school-aged children to occupational what is being taught. Illegible writing is a barrier in mathemat-

therapy in North America (Oliver, 1990; Cermak, 1991). In ics and could bias test grades.

the United Kingdom, children with different specific develop-

mental disorders (for example, dyspraxia or dyslexia), referred Development of handwriting skills

to the paediatric occupational therapy services, always experi-

ence difficulties in developing efficient handwriting skills. It is Levine (1987, p315) viewed handwriting as 'the final common

a common treatment area addressed by occupational thera- pathway, the merger of multiple developmental functions'.

pists, who can provide important opportunities for the child to Despite the diverse readiness skills needed for writing, by the

master the skill of handwriting. age of 6 or 7 years many children, via a traditional instruction-

This article outlines a conceptual framework which guides al approach, are fairly proficient at writing in school settings.

occupational therapists in developing comprehensive evalua- Table 1 summarises the main stages in the development of

tion procedures and effective intervention. Background infor- handwriting skills (based on Kellogg, 1969; Klein, 1982;

mation related to the functions and dysfunctions of handwrit- Erhardt, 1982; Department of Education and Science, 1989;

ing skills are reviewed. The performance components and Amundson and Weil, 1996).

functional performance of handwriting within a specific set of

performance contexts is discussed through a conceptual Prerequisite skills

model of practice. Procedures on evaluation and intervention There are many prerequisite skills for handwriting instruction.

strategies are outlined with information to support an evi- They include the abilities to balance without the use of hands,

dence-based practice. grasp and release an object voluntarily, use the hands in a led

and assisted fashion, interact with the environment in the

Background information stage of constructive play, hold utensils and writing tools and

Although no comprehensive and widely accepted theoretical form basic strokes smoothly, and also the perception of let-

Sidney Chu, ProfDipOT, certNDT(Bobath), PostgradDip(Biomechanics), CertSIPT(SII), BDADip(Dyslexia), MSc(Health Psychology), SROT, OTR,

Community Occupational Therapy Service Coordinator, West london Healthcare NHS Trust, Windmill lodge, Uxbridge Road, Southall UB13EU.

514 British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1997, 60(12)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com by guest on January 29, 2015

Table 1. Developmental stages of handwriting skills that 1.6 million adults in the United Kingdom had difficulties

Age levels Developmental stages with handwriting (Alston and Taylor, 1990).

1-1112 years Palmar - supinate grasp

Scribbles on paper Diagnostic terms

Types of scribbles: wavy, circular, variegated, There are different terms being used by different medical, psy-

looser variegated or combined chological, educational and therapy professionals to describe

Imitates scribbles a child with a form of handwriting or handwriting-related diffi-

culties. The two most common ones are 'developmental dys-

2-3 years Digital - pronate grasp graphia' and 'developmental disorder of written expression'.

Imitates vertical, horizontal and circular strokes Developmental dysgraphia is a written-language disorder

on paper that concerns mechanical writing skill. It manifests itself in

Imitates two or more strokes for a cross poor handwriting performance in children of at least average

intelligence who do not have a distinct neurological disability

3-4 years Transits to static tripod posture and/or an overt perceptual-motor handicap (Hamstra-Bietz

Copies a vertical line, horizontal line and circle and Blote, 1993). It may contribute significantly to a child's

Traces diamond, but with angles rounded learning difficulty or disability and is a matter of both educa-

Imitates cross tional and medical significance (Gubbay and de Klerk, 1995).

Developmental disorder of written expression is a type of

4-5 years Static or dynamic tripod posture

learning disorder described in the Diagnostic and Statistical

Copies a cross, right oblique line, square, left Manual of Mental Disorder, DSM-IV (APA, 1994). The essen-

oblique line and oblique cross tial feature of the disorder of written expression is the failure

Copies some letters and numbers to achieve expected writing skill as measured by lndlvidually

May be able to write own name administered standardised tests. Common symptoms include

excessively poor handwriting and the inability to compose sen-

5-6 years Stable dynamic tripod posture

tences or coherent paragraphs as indicated by multiple gram-

Copies triangle and diamond matical, spelling and punctuation errors (Rapoport and

Prints own name Ismond,1996).

Copies most lower and upper case letters Handwriting problems are also a common feature in chil-

Begins to form letters with some control over dren with the diagnosis of developmental coordination disor-

size, shape and orientation of letters, or lines of der, developmental dyspraxia, developmental dyslexia or sen-

writing sory integrative dysfunctions.

6-7 years Produces legible upper and lower case letters

in one style and uses them consistently (that A conceptual model for

is, not randomly mixed within words) performance in handwriting

Produces letters that are recognisably formed It is important for each occupational therapist to adopt a con-

and properly orientated and that have clear ceptual model of practice so that systematic evaluation and

ascenders and descenders where necessary treatment programmes can be implemented. Kielhofner

(1992) described a model as a theoretical framework that

8-10 years Begins to produce clear and legible joined-up explains some phenomena of practical concern (that is,

writing focus), describes the theoretical arguments (that is, functions

Produces clear and legible writing in both print- and dysfunctions) and provides a rationale and methods for

ed and cursive styles evaluation and therapeutic interventions. It offers a generic

Based on: Kellogg (1969), Klein (1982), Erhardt (1982), Department outline of the domains of concern of occupational therapy.

of Education and Science (1989), Amundson and Wei! (1996). The profession has categorised and defined itself as one

that encompasses human performance components which

ter and orientation to printed language (Donoghue, 1975; serve as the basis for different occupational performance

Lamme, 1979; Klein, 1982). areas, within a specific set of performance contexts. It is

Beery (1989) proposed that a child will be ready for formal recognised that the phenomena that constitute the profes-

instruction in handwriting if he or she manages to master the sion's domains of concern can be categorised and labelled in

first eight figures of the Developmental Test of Visual-Motor a number of different ways. In this article, the information is

Integration (VMI). The eight figures are vertical line, horizontal organised into the Conceptual Model for Performance in

line, circle, cross, right oblique line, square, left oblique line Handwriting. Some of the terms and concepts used are based

and oblique cross. Maeland (1992) also found that visual- on the Uniform Terminology for Occupational Therapy, pub-

motor skill as measured by the VMI was significant in predict- lished by the American Occupational Therapy Association

ing the accuracy of handwriting performance. (AOTA, 1994).

Prevalence of handwriting difficulties Performance components

DiffiCUlty with handwriting is a common problem in both chil- Performance components (AOTA, 1994) are fundamental

dren and adults. Often the teaching of handwriting is not human abilities that are required for successful engagement

emphasised in the early years of education and problems in performance areas. There are three performance compo-

begin at that stage. Rubin and Henderson (1982) identified nents:

that 12% of 9-10 year old pupils in a London borough had 1. Sensory, perceptual, praxis and motor functions

handwriting difficulties. The secondary school curriculum 2. Cognitive functions

makes new and complex demands on handwriting skills and 3. Psychosocial functions.

pupils may be ill-prepared for those demands. White (1986) There are many prerequisites to handwriting. Readiness

found that 10% of ll-year-olds still had handwriting difficul- involves different sensory, perceptual, motor, cognitive and

ties. In the 1990 International Literacy Year, it was estimated language functions, and the complex integrations of these

British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December1997, 60(12) 515

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com by guest on January 29, 2015

functions. Awareness of the underlying functions involved and analysed the developmental progress of pencil grip and found

their development can provide a framework for looking at the that about one-quarter of children aged 5 years 0 month to 6

child who is experiencing handwriting difficulty. years 11 months adopted the lateral tripod grip. Recent stud-

Levine et al (1981) identified that children with poor ies have found that adults and children with good handwriting

kinaesthetic perception could not develop the automaticity of skills use a wide variety of pencil grip patterns and that an

manual handwriting. Schneck (1991) suggested that proprio- atypical grasp pattern by itself does not necessarily result in

ceptive-kinaesthetic ability and hand preference in children handwriting difficulties (Ziviani and Elkins, 1984; Ziviani,

with poor grip should be assessed routinely. Maeland (1992) 1987; Schneck and Henderson, 1990; Schneck, 1991).

identified that handwriting difficulties were significantly related Occupational therapists should consider all three elements

to poor visual-motor integration and visual form perception in in order to access a child's functional performance of hand-

a group of clumsy children. According to Exner (1989), the writing in either manuscript (print) or cursive (ioined script), or

three aspects of fine motor control that affect handwriting are both. It is important to assist the educational team and par-

isolation of movements, grading of movements and timing of ents in identifying the child's problematic areas of handwriting

movements. as well as to establish the child's baseline of handwriting

Tseng and Murray (1994) studied 143 Chinese children function.

(71 with problems and 72 without problems in handwriting) in

grades 3 to 5. A battery of perceptual-motor tests proposed to

Performance contexts

measure the subskills of handwriting was administered along

with a handwriting test. The results showed that (a) poor Performance contexts (AOTA, 1994) are situations or factors

handwriters scored worse than good handwriters on most of that influence an individual's engagement in desired and/or

the perceptual-motor tests; (b) visual-motor integration and required performance areas. There are two aspects of perfor-

eye-hand coordination contributed most to the legibility of mance contexts:

handwriting for the total group of handwriters; (c) however, for 1. Temporal aspects, for example, chronological, developmen-

poor handwriters, motor planning function contributed the tal, life cycle and disability status

most to the legibility of handwriting; and (a) for good handwrit- 2. Environmental aspects, for example, physical, social, cul-

ers, visual perception contributed most to the legibility of tural and spiritual.

handwriting.

These research studies demonstrate the importance of The conceptual model

evaluating and treating any potential deficits in the perfor-

There is an interactive relationship among performance areas,

mance components, especially the sensorimotor component,

performance components and performance contexts. Function

of handwriting skills.

in performance areas within a specific set of performance

contexts is the ultimate concern of occupational therapy.

Performance areas (functional performance) Identified deficits in performance components should be con-

sidered as they relate to participation in different performance

Performance areas (AOTA, 1994) are broad categories of

areas. For example, a child's diffiCUlty in handwriting (that is,

human functional activities that are typically part of daily life.

performance areas) could be related to poor visual form per-

There are three performance areas:

ception and poor visual-motor skills (that is, performance

1. Activities of daily livmg

components). Treatment should be directed at remediating

2. Work/school and productive activities

these underlying dysfunctions with consideration of the child's

3. Play or leisure activities.

age, health status and other environmental factors (that is,

Handwriting is one of the work/school and productive activi-

performance contexts).

ties. Some controversy exists as to when children are ready

The interaction between the performance components and

for formal handwriting instruction. Differing rates of maturity,

functional performance in handwriting is expressed through

environmental experiences and interest levels are all factors

the Conceptual Model for Performance in Handwriting, as

that can influence children's early attempts and successes in

illustrated in Fig. 1. A conceptual model is an organising tech-

copying letters. Some children may be ready for writing at age

nique designed to assist in categorising ideas and structuring

4, and others may not be ready until age 6 (Lamme, 1979;

approaches to thinking about complex problems (Hurtt,

Laszlo and Bairstow, 1984). When evaluating the actual task

1985). It helps occupational therapists to be clear about what

of children's handwriting, there are three elements that war-

they are doing and why, so that they can identify their unique

rant attention:

role and set a professional boundary (Creek and Feaver,

1. Biomechanical and ergonomic factors, for example, sitting

1993). It emphasises the concept of thinking like an occupa-

posture, pencil grip, and writing tools and papers

tional therapist (Hansen and Atchison, 1993).

2. Quality of writing, for example, levelling, directionality and

spacing in letter formation

Fig. 1. Conceptual Model for Performance in Handwriting.

3. Observations/other considerations, for example, associated

Deficits In the following ... will affect a child's functional

reactions and behavioural responses.

performance components performance In handwriting

One of the most neglected classroom prerequisites for effi-

_ Sensory, perceptual, praxis _ Biomechanical and ergonomic

cient handwriting is assuming and maintaining a balanced sit-

and motor functions factors

ting posture (Benbow et at, 1992). Alston and Taylor (1987)

_ Cognitive functions _ Quality of writing

identified significant contributions to handwriting illegibility by

analysing 100 handwriting samples of 7- and 8-year-old chil- _ Psychosocial functions _ Emotional and behavioural

dren in England. In letter formation, they found that the most responses

common characteristics included: (a) incorrect letter forms; *Based on AOTA (1994).

(b) inadequate 'leading in' and 'leading out' of letters; (c) poor

rounding of letters; (d) incomplete letter closure; and (e) inad-

equate letter ascenders and descenders. Evaluation of handwriting skills

There are also many research studies investigating the Evaluation is defined as the planned process of obtaining and

development and effect of different pencil grips on a child's interpreting the objective/subjective and quantitative/qualita-

handwriting performance. Schneck and Henderson (1990) tive data necessary for treatment. Occupational therapy evalu-

516 British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1997, 60(12)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com by guest on January 29, 2015

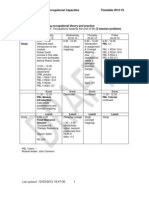

ation involves examining performance areas, performance Table 3. Handwriting profile

components and performance contexts. Accurate and relevant Performance components Functional performance

assessment data are required to set specific goals and objec- A. SENSORIMOTOR A. BIOMECHANICAL AND

COMPONENTS ERGONOMIC FACTORS

tives in programme planning. It also provides a baseline to

1. sensory processing 1. Furniture - size, height

monitor the child's handwriting progress. functions 2. Body posture

- Registration, Upright posture, trunk

modulation, discrimination position

Assessment procedures - Tactile, proprioceptive, - Head position, leg

vestibular

When a child with poor handwriting performance has been position

referred to occupational therapy, the methods of gathering 2. Perceptual processing

3. Shoulder posture

functions

objective and subjective information must be carefully select- - Shoulder position,

(a) Body perception

scapula position

ed and sequenced. A comprehensive evaluation of a child's (b) Tactile perception

- Humerus position,

handwriting function includes the following assessment proce- (c) Kinaesthetic perception

righVleft sides

(d) Vision

dures (Amundson and Weil, 1996): (a) examining written work

(e) Visual perception 4. Forearm posture

samples; (b) discussing the child's performance with the (f) LefVright orientation 5. Hand and wrist posture

teacher, parents, and other team members; (c) reviewing the (g) Auditory perception - Wrist stability, wrist

child's educationaVclinical record; (d) directly observing the 3. Postural-motor control mobility

child when he or she is writing in the natural setting; (e) eval- (a) Muscle tone - Hook wrist

(b) Reflex integration - Intrinsic muscles,

uating the child's functional performance of handwriting, that

(c) Postural control transverse arches

is, biomechanicaVergonomic factors, and quality of writing; - Prone extension

and (f) assessing any suspected interfering performance com- 6. Handedness

- Supine flexion

ponents related to handwriting, that is, sensorimotor, cognitive - Midline/central 7. Writing tools

stability

and psychosocial factors. (d) Shoulder

8. Pencil grip

- Stability 9. Tension of grip

- Mobility 10. Type of paper

Handwriting evaluation tools (e) Dynamic forearm

rotation 11. Pressure on paper

Formal or standardised tests are critical in the assessment of

(f) Wrist 12 Bilateral integration -

children because they provide objective measures and quanti- - Stability stabilisation of paper,

tative scores, aid in monitoring a child's progress, assist pro- - Mobility crossing midline

fessionals to communicate more clearly and advance the field (g) Hand muscle strength

(h) Hand arches 13. Paper position - initial

through research (Campbell, 1989). A number of formal or (i) Thumb stability position, adjustment

standardised handwriting evaluation tools have been devel- fj) Fine motor control 14 Posturalbac~ound

oped by different occupational therapists and psychological - Isolation of movement - midline stability,

and educational professionals (see Table 2). Most of these movements compensatory movement

- Grading of

tools have been developed in North America, with the use of movements B. QUAUTY OF WRmNG

writing styles different from those used in the United Kingdom. _ Timing of movements 1. Basic writing patterns

(k) In-hand manipulation 2. Writing style - printing,

Table 2. Handwriting evaluation tools - Finger to palm joined up, full cursive

- Palm to finger

Type Tools _ Within finger 3. Letter/number formation

Criterion-referenced Denver Handwriting Analysis (Anderson, 1983) (I) Isolation of arm - Directionality, spacing,

movements slant

Diagnosis and Remediation of Handwriting (m)Precise interplay - Levelling, size, curve

Problems (Stott et ai, 1985) between opposing formation

muscle groups - Letter closure, letter

The Handwriting File (Alston and Taylor, 1988)

(n) Bilateral integration orientation

Evaluation Tool of Children's Handwriting - Laterality - Joined up, ascenders!

ETCH (Amundson, 1996) - Crossing body descenders

midline - Distortions, collisions,

Norm-referenced Children's Handwriting Evaluation Scale - CHES - Hand dominance ambiguous

- Bilateral motor co- 4. Sequencing of letters

(Phelps et al, 1984)

ordination

Children's Handwriting Evaluation Scale for (0) Ocular-motor control 5. Phoneme - grapheme

Manuscript Writing - CHES-M (Phelps and (p) Visually-dtrected hand 6. Writing speed and endurance

movements - speed, endurance

Stempl, 1987)

4. Praxis 7. Upper/lower case

Minnesota Handwriting Test - Research Version (a) Central processes

(Reisman, 1987, 1991) _ Ideation 8. General impression -

_ Motor planning legibility, consistency,

Test of Legible Handwriting (Larsen and _ Execution neatness

Hammill,1989) (b) Sequencing C. OTHER OBSERVATIONS/

(cl Spatial organisation CONSIDERAnONS

(d) Graphic praxis For example,

For tool selection, the occupational therapist should keep (e) Constructional praxis _ Associated reactions

in mind the characteristics of each instrument as well as the (f) Auditory-motor - Associated movements

strengths and limitations of the tests regarding normative integration _ Squirms and fidgets

data, reliability and validity, and other psychometric proper- B. COGNITIVE COMPONENTS - Vocalisation

ties. It is important to go beyond standardised tests to gather 1. Attention - Fatigue

2. Memory - Frustration

qualitative information and to observe how the deficits in per- - Resistance to task

3. Language - comprehension

formance components will affect a child's functional perfor- - Impulsiveness

4. Reasoning

mance in handwriting. - Worried about mistakes

A handwriting profile (see Table 3) has been developed for C. PSYCHOSOCIAL COMPONENTS - Constant erasures

1. Emotional stability - Timid and nervous

clinical practice (Chu, 1997). It summarises qualitatively the - Hesitation

2. Self-esteem

child's level of function in different areas of performance com- 3. Motivation - Dislikes writing

ponents and functional performance of handwriting skill. 4. Self-control - Avoidance

British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December1997, 60(12) 517

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com by guest on January 29, 2015

Treatment planning Remedial approaches

Occupational therapists may be instrumental in developing a Remedial approaches emphasise facilitating the improvement

handwriting remediation programme to be integrated into the of performance components, such as perceptual training. A

child's educational plan. The following points should be con- child may have deficits in different aspects of the three perfor-

sidered in the whole treatment planning process. mance components that affect his or her development of

handwriting skills, such as sensory processing dysfunctions,

perceptual processing dysfunctions, deficits in postural-motor

Setting goals and objectives of treatment control and praxis, specific cognitive dysfunctions and psy-

Goals of treatment should be established in collaboration with chosocial disturbances.

the parents, teachers and, if possible, the child involved at It is impossible to cover the relevant treatment strategies

the early stage of treatment planning. Specific objectives for all aspects of the performance components in this article.

should be selected as an indicator of progress and improve- It is important to note that (a) if a child has an underlying sen-

ment. The goals and objectives selected should be realistic, sory integrative dysfunction which contributes to the child's

achievable, observable and measurable. presenting problem in handwriting skills, then sensory integra-

tive therapy should be the first choice of remediation; and (b)

if a child has specific deficits in the perceptual processing

Treatment principles functions and/or perceptual-motor functions without an under-

Therapists should be sensitive to the child's needs because lying sensory integrative dysfunction, then perceptual and/or

handwriting difficulties may cause frustration and anxiety. The perceptual-motor training will be appropriate as a remediation

therapist assists in this learning process by creating an envi- approach.

ronment that encourages a positive change in the child's

behaviour (Todd, 1993). Teaching principles are used by the

therapist to help a child process information in a meaningful Functional approaches

way; for example, the therapist selects activities and creates Functional approaches emphasise facilitating mastery of

an environment which reflect a child's aptitude; considers tasks, such as manual writing skills training. Handwriting may

motivational factors; engages the child actively in the task; be viewed as a complex sensorimotor skill and, like other

begins training at the child's current level of functioning and acquisitional skills, can be improved through practice, repeti-

proceeds at a rate that is comfortable for him or her; and tion, feedback and reinforcement (Holm, 1986). Graham and

uses positive reinforcement and feedback (Mosey, 1986). Miller (1980) recommended that instructional guidance in

handwriting be (a) taught directly; (b) implemented in brief

daily lessons; (c) matched to individual needs of the child; (d)

Collaboration between occupational therapist

planned and changed based on evaluation and performance

and teacher data; and (e) used in a meaningful manner by the child.

Occupational therapy is process-orientated, while education is The instructional approaches of handwriting intervention

product-orientated. The teacher is primarily responsible for methods vary but tend to include a combination of sequential

handwriting instruction; 'the therapist's role is to determine techniques, such as modelling, tracing, copying, composing,

underlying postural, motor, sensory integrative, or perceptual stimulus fading and self-monitoring (Milone and Wasylyk,

deficits that might interfere with the development of legible 1981; Bergman and Mclaughlin, 1988). When therapists and

handwriting' (Stephens and Pratt, 1989, p311). Both aspects educators employ these conditions in a positive, interesting

of intervention are important. Collaboration should be estab- and dynamic learning environment, children are more likely to

lished at the early stage of evaluation and intervention. become efficient, legible writers (Milone and Wasylyk, 1981;

Barchers, 1994).

Service delivery models

Providing occupational therapy services to children with hand- Compensatory approaches

writing dysfunction should be based primarily on the needs of Compensatory approaches emphasise minimising the effect of

the individual child. Occupational therapy service delivery in deficits in performance components in areas of functional per-

mainstream schools has typically been implemented with formance, for example, the use of tape to indicate the proper

three models: (a) direct therapy, (b) monitoring and (c) con- positioning of paper on desk and the use of audio-tape.

sultation (Dunn, 1991; Mosey, 1993). Therapists could use a

continuum of service delivery models that allows for more flex-

ibility, fluidity and responsiveness to an individual child's Adaptive approaches

needs. Adaptive approaches emphasise changing the task, or aspects

Therapists also need to consider other factors when help- of the environment, to minimise the effect of deficit in perfor-

ing a child with handwriting difficulties, such as the school mance subcomponents and/or related behaviours on areas of

policy on handwriting, the demands of the National Curri- occupational performance; for example, reducing the amount

culum, the expectations of the parents, the teacher and the of copying task and putting the main points or headings on

child, and the resources of the service. paper.

Service provision approaches and Management approaches

treatment approaches Management approaches emphasise minimising distressing or

Occupational therapists adopt different service provision disruptive feelings and behaviour so that the individual is able

approaches to address the specific needs of a child with to deal more directly with primary problems, such as psycho-

handwriting difficulties. An intervention programme is devised logical support and praise/reward. The results of different

by integrating relevant techniques from different treatment research studies indicate that relaxation training can help to

approaches (see Table 4). The six service provision approach- improve handwriting performance by reducing muscle tension

es (Mosey, 1993) which may be used concurrently and/or (Carter and Synolds, 1974; Jackson and Hughes, 1978;

sequentially in intervention are as follows. Hugheset at, 1979; Jackson et ai, 1980).

518 British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December1997, 60(12)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com by guest on January 29, 2015

Maintenance approaches out critical appraisal of information, and (e) constantly evalu-

ate their own performance.

Maintenance approaches emphasise preserving and support-

ing an individual's current level of function, in a protected A major part of the occupational therapy programme aims

at remediating the child's underlying dysfunctions in different

environment, such as the use of a voice-activated computer.

performance components. There are many research studies

providing evidence to support this area of occupational thera-

Table 4. Occupational therapy service provision ap- py. For example, Furner (1967) emphasised the need for

proaches (Mosey, 1993) and treatment ap-

handwriting programmes with verbalisation and perceptual-

proaches for children with handwriting difficul-

process training. Strayer and Ames (1972) found that chil-

ties

dren's ability to copy designs improved after a brief period of

Service provision Treatment approaches

visual-perceptual training that emphasised the orientation of

approaches

figures. Jennings (1974) showed a positive and significant

Remedial Sensory integrative therapy

relationship between the ability to manipulate objects and the

Sensorimotor therapy ability to copy designs. Laszlo and Bairstow (1983, 1984)

Neurodevelopmental treatment found long-term benefits after using a kinaesthetic and sensi-

Perceptual-motor programmes tivity training programme with 7- and 8-year-old children. Stott

Visual perceptual training et al (1987) recommended the development of a motor

Fine-motor and visual-motor skill training scheme which emphasised large movement patterns along

Pre-writing training(Klein, 1982) with a smooth, fluid motion. Oliver (1990) demonstrated sig-

nificant improvement in the writing readiness skills of a group

Functional Biomechanical and ergonomic interventions, of children aged 5 to 7 years after the use of a sensorimotor

such as sitting posture, pencil grip programme.

Acquisitional (instructional) approach

Alphabet work

Multisensory techniques

Conclusion

Kinaesthetic writing (Benbow, 1990) Handwriting is an important academic occupation for children.

Children in mainstream education with specific developmental

Mystery writing

disorders are often referred to occupational therapy with the

Rainbow writing

primary reason for referral being handwriting dysfunction.

Guided writing (Price, 1986)

Occupational therapists possess the skills and expertise to

Self-evaluation checklist make important contributions to interventions regarding hand-

Compensatory Use of audio-tepe writing dysfunction. An extensive neuromuscular and sensori-

Laptop computer/electric typewriter motor background, experience with functional training, knowl-

edge about psychological and social behaviour, competence in

Keyboard skill training

analysing complex activities, and the capacity for making the

Someone to do the writing

most boring task enjoyable are all attributes that empower

Colour code to indicate orientation occupational therapists to evaluate and treat children with

Adaptive Reduce the amountof copying task handwriting problems expertly (Cunningham, 1992).

Put main pointsor headings on paper The role of the occupational therapist in evaluating and

treating a child's functional performance of handwriting skills

Adaptive devices or tools, such as pencil grip,

is highlighted through a conceptual model of practice. It is

Write Angle, special lined paper, adjustable fur-

emphasised that handwriting intervention programmes should

niture

be comprehensive, incorporating activities and therapeutic

Management Motivational approach - intrinsic and extrinsic techniques from different remediation and functional

Reinforcement programme, such as token approaches. Different adaptive, compensatory, management

economy, star chart, praise/reward and maintenance strategies may also be employed to provide

the child with a successful and efficient means of coping with

Relaxation training

demands in the natural setting.

Peer group support It is also important to set clear criteria of referral, to devel-

Coping skill training op valid and reliable screening and evaluation instruments, and

Maintenance High power information technology appli- to carry out scientific research to validate further the efficacy of

occupational therapy for children with handwriting difficulties.

ances

Voice-activated computer

References

Alston J, Taylor J (1987) Handwriting: theory, research and practice.

London: Croom Helm.

Evidence-based practice Alston J, Taylor J (1988) The handwriting file. Wisbech, Cambs: LOA.

Alston J, Taylor J (1990) Handwriting helpline. Manchester: Dextral

In recent years, evidence-based health care and clinical effec- Books.

tiveness have become popular topics (Appleby et ai, 1995). Amundson ST (1996) Evaluation tool of children's handwriting. Homer,

The National Health Service Executive and the Department of AK: OT KIDS.

Health have made improving clinical effectiveness a key NHS Amundson SJC, Wei! M (1996) Prewriting and handwriting skills. In: J

Case-Smith, AS Allen, PN Pratt, eds, Occupational therapy for chil-

priority for the last 3 years, and have invested heavily in fos-

dren. Chicago: Mosby.

tering evidence-based practice (NHS Executive, 1996). Anderson PL (1983) Denver handWriting analysis. Novato, CA:

Davidoff et al (1995) described evidence-based practice as Academic Therapy Publications.

the processes in which health care professionals (a) make AOTA (1994) Uniform terminology for occupational therapy - 3rd edi-

clinical decisions based on the best available scientific evi- tion. American Journal of OCcupational Therapy, 48, 1047-54.

APA (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder (IV

dence, (b) seek and select evidence to meet a clinical prob- ed), Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

lem rather than habits or protocols, (c) use epidemiological Appleby J, Walshe K, Ham C (1995) Acting on the evidence.

and biostatistical ways of thinking about evidence, (d) carry Birmingham: NAHAT.

Briosh Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1997, 60(12) 519

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com by guest on January 29, 2015

Barchers SI (1994) Teaching language arts: an integrated approach. Kielhofner G (1992) Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy.

Minneapolis: West Publishing. Philadelphia: FA Davis.

Beery KE (1989) The developmental test of visual-motor integration Klein MD (1982) Prewriting skills. Tucson, Arizona: Communication

(3rd revision). Cleveland: Modern Curriculum Press. Skill Builders.

Benbow M (1990) Loops and other groups. Tucson, Arizona: Therapy Lamme LL (1979) Handwriting in an early childhood curriculum. Young

Skill Builders. Children, 35(1), 20-27.

Benbow M, Hant B, Marsh D (1992) Handwriting in the classroom: Larsen SC, Hamill DD (1989) Test of legible handwriting. Austin, TX:

improving written communication. In: CB Royeen, ed. AOTA Self- PRO-ED.

Study series: Classroom applications for school-based practice. Laszlo JI, Bairstow PJ (1983) Kinaesthesis: its measurement, training

Lesson 4. Rockville, MD: American Occupational Therapy and relationship to motor control. Quarterly Journal of Experimental

Association. Psychology, 35A, 411-21.

Bergman KE, Mclaughlin TF (1988) Remediating handwriting difficul- Laszlo JI, Bairstow PJ (1984) Handwriting: difficulties and possible

ties with learning disabled students: a review. Journal of Special solutions. School PsychologyInternational, 5, 207-13.

Education, 12, 101-20. Levine M (1987) Developmental variation and learning disorders.

Campbell SK (1989) Measurement in developmental therapy: past, Cambridge, MA: Educators Publishing, 315.

present, and future. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Levine MD, Oberklaid F, Meltzer L (1981) Developmental output fail-

Pediatrics, 9, 1-14. ure: a study of low productivity on school aged children. Pediatrics,

Carter JL, Synolds D (1974) Effects of relaxation training upon hand- 67,18-25.

writing quality. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 7, 53-55. Maeland AE (1992) Handwriting and perceptual-motor skills in clumsy,

Cermak S (1991) Somatosensory dyspraxia. In: A Fisher, EA Murray, dysgraphic, and 'normal' children. Perceptual-Motor Skills, 75,

AC Bundy, eds. Sensory integration: theory and practice. 1207-17.

Philadelphia: FA Davis, 138-70. Milone MN, Wasylyk TM (1981) Handwriting in special education.

Chu S (1997) Course handbook - Assessment and treatment of chil- Teaching Exceptional Children, 14, 58-61.

dren with handwriting difficulties. Unpublished teaching material. Mosey AC (1986) Psychosocial components of occupational therapy.

London: West London Healthcare NHS Trust. New York: Raven Press.

Creek J, Feaver S (1993) Models for practice in occupational therapy: Mosey AC (1993) Introduction to cognitive rehabilitation - working tax-

part 2, what use are they? British Journal of Occupational Therapy, onomies. In: CB Royeen, ed. AOTA Self-Study Series: Cognitive

56(2), 59-62. rehabilitation. Rockville, MD: American OCcupational Therapy

Cunningham SJ (1992) Handwriting: evaluation and intervention on Association.

school settings. In: J Case-Smith, C Pehoski, eds. Development of NHS Executive (1996) Priorities and planning guidance for the NHS

hand skills in the child. Rockville, MD: American Occupational 1997-98. Leeds: NHS Executive.

TherapyAssociation. Oliver CE (1990) A sensorimotor programme for improving writing

Davidoff F, et al (1995) Evidence-based medicine. British Medical readiness skills in elementary-age children. American Journal of

Journal, 310, 1085-86. Occupational Therapy, 44(2), 111-16.

Department of Education and Science (1989) English in the National Phelps J, Stempl L (1987) The children's handwriting evaluation scale

Curriculum. London: HMSO. for manuscript writing. Dallas, TX: Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for

Donoghue M (1975) The child and the English language arts. 2nd ed. Crippled Children.

Dubuque, IA: William C Brown. Phelps J, Stempl L, Speck G (1984) The children's handwriting evalua-

Dunn W (1991) Paediatric occupational therapy - facilitating effective tion scale: a new diagnostic tool. Dallas, TX: Texas Scottish Rite

service provision. Thorofare, NJ: Slack. Hospital for Crippled Children.

Erhardt RP (1982) Developmental hand dysfunction: theory, assess- Price A (1986) Applying sensory integration to handwriting problems.

ment, treatment. Laurel, MD: Ramsco. AOTA Developmental Disabilities Special Interest Section

Exner CE (1989) Development of hand functions. In: PN Pratt, AS Newsletter, 9(3), 4-5.

Allen, eds, Occupational therapy for children. St Louis, MO: Mosby. Rapoport JC, Ismond DR (1996) DSM-IV training guide for diagnosis of

Furner B (1967) The development of a programme of instruction for childhood disorders. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

beginning handwriting emphasising verbalisation of procedures to Reisman JE (1987) Minnesota handwriting test (research version).

increase perception and an analysis of the effectiveness of this pro- Unpublished manuscript. Universityof Minnesota.

gramme through comparison with a commercial method. Reisman JE (1991) Poor handwriting: who is referred? American

Dissertation Abstracts International, 28(02-A), 389 (University Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(9), 849-52.

Microfilms No. 67-09056). Rubin N, Henderson SE (1982) Two sides of the same coin: variations

Graham S, Miller L (1980) Handwriting research and practice: a unified in teaching methods and failure to learn to write. Special

approach. Focus of Exceptional Children, 13, 1-16. Education: Forward Trends, 9(4), 17-24.

Gubbay SS, de Klerk NH (1995) A study and review of developmental Schneck CM (1991) Comparison of pencil grip patterns in first graders

dysgraphia in relation to acquired dysgraphia. Brain and with good and poor writing skills. American Journal of Occupational

Development, 17, 1-8. Therapy, 45(8), 701-706.

Hagin RA (1983) Write right - or left: a practical approach to handwrit- Schneck CM, Henderson A (1990) Descriptive analysis of the develop-

ing. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 16(5), 266-71. mental progression of grip position for pencil and crayon control in

Hamstra-Bietz L, Blote AW (1993) A longitudinal study on dysgraphic nondysfunctional children. American Journal of OCcupational

handwriting in primary school. Journal of Learning Disabilities, Therapy, 44(10), 893-900.

26(10), 689-99. Stephens LC, Pratt PN (1989) School work tasks and vocational readi-

Hansen RA, Atchison B (1993) Conditions in occupational therapy - ness. In: PN Pratt, AS Allen, eds. Occupational therapy for children.

effect on occupational performance. Baltimore: Williams and St Louis: Mosby, 311-34.

Wilkins. Stott DH, Henderson SE, Moyes FA (1987) Diagnosis and remediation

Holm M (1986) Frames of reference: guides for action - occupational of handwriting problems. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 4,

therapist. In: HS Powell, ed. PILOT: Project for Independent Living in 137-47.

Occupational Therapy. Rockville, MD: American Occupational Stott DH, Moyes FA, Henderson SE (1985) Diagnosis and remediation

Therapy Association, 69-78. of handwriting problems. Guelph, Ontario: Brook Educational

Hughes H, Jackson K, DuBois KF, Ervin R (1979) Treatment of hand- Publishing.

writing problems utilising EMG biofeedback training. Perceptual and Strayer J, Ames EW (1972) Stimulus orientation and the apparent

Motor Skills, 48, 603-605. developmental lag between perception and performance. Child

Hurtt JM (1985) Visualisation: a' decision making tool for assessment Development, 43, 1345-54.

and treatment planning. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 1(2), Todd VR (1993) Visual perceptual frame of reference: an information

5-12. processing approach. In: P Kramer, J Hinojosa, eds. Frames of ref-

Jackson KA, Hughes H (1978) Effects of relaxation training on cursive erence for paediatric occupational therapy. Philadelphia: Williams

handwriting of fourth-grade students. Perceptual and Motor Skills, and Wilkins.

51, 1214-21. Tseng MH, Murray EA (1994) Differences in perceptual-motor mea-

Jackson KA, Jolly V, Hamilton B (1980) Comparison of remedial treat- sures in children with good and poor handwriting. OCcupational

ments for cursive handwriting of fourth-grade students. Perceptual Therapy Journal of Research, 14(1), 19-36.

and Motor Skills, 51, 1215-21. White J (1986) The assessment of writing: pupils aged 11 and 15.

Jennings PA (1974) Haptic perception and form reproduction by Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

kindergarten children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Ziviani J (1987) Pencil grasp and manipulation. In: J Alston, J Taylor, eds.

28, 274-80. Handwriting: theory, research and practice. London: Croom Helm.

Kellogg R (1969) Analysing children's art. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Ziviani J, Elkins J (1984) Effect of pencil grip on handwriting speed and

Publishing. legibility. Educational Review, 38, 247-57.

520 British Journal of Occupational Therapy, December 1997, 60(12)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com by guest on January 29, 2015

Вам также может понравиться

- The Tale of Despereaux - Literature Kit Gr. 3-4От EverandThe Tale of Despereaux - Literature Kit Gr. 3-4Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2416)

- Gangguan Belajar AnakДокумент28 страницGangguan Belajar AnakAgung Hari WibowoОценок пока нет

- A Frame of Reference For The WritingДокумент29 страницA Frame of Reference For The WritingkuraОценок пока нет

- Psychology For Exceptional Children Lesson 5Документ4 страницыPsychology For Exceptional Children Lesson 5helienamarionsaliОценок пока нет

- Strategies For Teaching Writing To Pupils With Dyslexia in A Mainstream and Small Group SettingДокумент6 страницStrategies For Teaching Writing To Pupils With Dyslexia in A Mainstream and Small Group SettingdavybunyipОценок пока нет

- PED 110 AssignmentДокумент2 страницыPED 110 AssignmentXiara Jean Angelica IgnacioОценок пока нет

- Why Children With Dyslexia Struggle With Writing and How To Help Them (Revision)Документ21 страницаWhy Children With Dyslexia Struggle With Writing and How To Help Them (Revision)MónicaОценок пока нет

- Teaching Strategies in Mtb-Mle Program: Teaching and Learning Languages and MultiliteraciesДокумент45 страницTeaching Strategies in Mtb-Mle Program: Teaching and Learning Languages and MultiliteraciesLydia Ela100% (7)

- Why Children With Dyslexia Struggle With Writing and How To Help ThemДокумент21 страницаWhy Children With Dyslexia Struggle With Writing and How To Help ThemLuis.fernando. GarciaОценок пока нет

- Every Child Is A Writer Understanding The Importance of Writing in Early Childhood WritingДокумент14 страницEvery Child Is A Writer Understanding The Importance of Writing in Early Childhood WritingYOLANDA ARZABALОценок пока нет

- Critical Reading AssignmentДокумент10 страницCritical Reading Assignmentnevra serinОценок пока нет

- Language and Literacy Disorders Sivaswetha RДокумент14 страницLanguage and Literacy Disorders Sivaswetha RSriram Manikantan100% (1)

- Interventions For Childrens Language and Literacy DifficultiesДокумент8 страницInterventions For Childrens Language and Literacy DifficultiesFernanda Espinoza DelgadoОценок пока нет

- HandwritingresoucesДокумент50 страницHandwritingresoucesnadeemuzairОценок пока нет

- Teaching T Ke-15 Chapter 18 SitiДокумент5 страницTeaching T Ke-15 Chapter 18 SitiSitti Khadija SamanОценок пока нет

- Learning DisabilitiesДокумент9 страницLearning Disabilities20DPCE079 SharikОценок пока нет

- Reading by The ColorsДокумент6 страницReading by The ColorsanimationeasyОценок пока нет

- Lectura y Escritura para FonoaudiologiaДокумент17 страницLectura y Escritura para FonoaudiologiaNatalia JimenezОценок пока нет

- Ot Guidelines Child SpecificДокумент34 страницыOt Guidelines Child Specific健康生活園Healthy Life Garden100% (1)

- Ej 967123Документ13 страницEj 967123api-248255971Оценок пока нет

- Culminating Performance Task: Case Study - Individual Literacy Assessment CPTДокумент7 страницCulminating Performance Task: Case Study - Individual Literacy Assessment CPTapi-455810519Оценок пока нет

- 14 Psychological Intervention For Specific Learning DisabilityДокумент5 страниц14 Psychological Intervention For Specific Learning Disabilityamrut muzumdarОценок пока нет

- Learning DisabilitiesДокумент25 страницLearning DisabilitiesJoana GatchalianОценок пока нет

- Learning Disabilities Victoria Smith & Jason Harnett Adapted Physical EducationДокумент27 страницLearning Disabilities Victoria Smith & Jason Harnett Adapted Physical EducationhayszОценок пока нет

- P.T. Kingston - Problems in Writing Disability Among The School ChildrenДокумент6 страницP.T. Kingston - Problems in Writing Disability Among The School ChildrenShanmugam Yamanaboina100% (1)

- Indian J. Edu. Inf. Manage., Vol. 1, No. 9 (Sep 2012) Issn 2277 - 5374Документ10 страницIndian J. Edu. Inf. Manage., Vol. 1, No. 9 (Sep 2012) Issn 2277 - 5374CatalinaIonОценок пока нет

- Teaching Handwriting and Correct Pencil GripДокумент37 страницTeaching Handwriting and Correct Pencil GripTeachers Grade 3Оценок пока нет

- CapelloДокумент13 страницCapelloapi-460709225Оценок пока нет

- WWW - Multidisciplinaryjournals.com:wp content:uploads:2015:03:PROBLEMS AFFECTING LEARNING WRITING SKILL OF GRADE 11Документ17 страницWWW - Multidisciplinaryjournals.com:wp content:uploads:2015:03:PROBLEMS AFFECTING LEARNING WRITING SKILL OF GRADE 11Lê Thị Phương Thảo E15Оценок пока нет

- Writing Skills ResearchДокумент10 страницWriting Skills ResearchLily ChanОценок пока нет

- List Down 3 Famous Filipino ScientistДокумент1 страницаList Down 3 Famous Filipino ScientistMilky Lescano LargozaОценок пока нет

- The Development of Fine Motor and Handwriting SkillsДокумент82 страницыThe Development of Fine Motor and Handwriting SkillsMaria AiramОценок пока нет

- Multiple IntelligencesДокумент19 страницMultiple IntelligencesAnita Madunovic100% (1)

- Dyslexia White PaperДокумент7 страницDyslexia White PaperS Symone WalkerОценок пока нет

- Dysgraphia PDFДокумент2 страницыDysgraphia PDFcassildaОценок пока нет

- The Comprehension Problems of Children With Poor Reading Comprehension Despite Adequate Decoding: A Meta-AnalysisДокумент43 страницыThe Comprehension Problems of Children With Poor Reading Comprehension Despite Adequate Decoding: A Meta-AnalysisChristina KiuОценок пока нет

- Mesiona El107 - Review Quiz Bsede-3Документ4 страницыMesiona El107 - Review Quiz Bsede-3Audrey Kristina MaypaОценок пока нет

- Polos Developmental Differences in Early Reading SkillsДокумент18 страницPolos Developmental Differences in Early Reading Skillsp_denok_Оценок пока нет

- ANA LIZA V. LEYVA - Assessment of Classroom Behavior and Academic AreasДокумент35 страницANA LIZA V. LEYVA - Assessment of Classroom Behavior and Academic AreasAna Liza Villarin AvyelОценок пока нет

- Effect of Story Mapping and Paraphrasing On The Reading Comprehension of Students With Learning Disabilities in Ikenne Local GovernmentДокумент15 страницEffect of Story Mapping and Paraphrasing On The Reading Comprehension of Students With Learning Disabilities in Ikenne Local GovernmentJesutofunmi Naomi AJAYIОценок пока нет

- Automated Human-Level Diagnosis of Dysgraphia Using A Consumer TabletДокумент9 страницAutomated Human-Level Diagnosis of Dysgraphia Using A Consumer TabletPawełGolińskiОценок пока нет

- Dyslexia Research PaperДокумент8 страницDyslexia Research Paperscxofyplg100% (1)

- DysgraphiaДокумент2 страницыDysgraphiaMarilu AdrianaОценок пока нет

- Hyperlexia PowerpointДокумент35 страницHyperlexia PowerpointKristen Coughlan100% (7)

- Cooper 2004Документ12 страницCooper 2004Kahina LETTADОценок пока нет

- Dyslexia - An Introductory Guide To Diagnosis: Richard WardДокумент37 страницDyslexia - An Introductory Guide To Diagnosis: Richard Wardwill 7Оценок пока нет

- PSYC0022 Dyslexia 2023Документ41 страницаPSYC0022 Dyslexia 2023Yan Yiu Rachel ChanОценок пока нет

- SEN Understanding Handwriting DifficultiesДокумент15 страницSEN Understanding Handwriting DifficultiesVerónica Ramos MonclaОценок пока нет

- Developing Writing Skills: Wendy GoldupДокумент23 страницыDeveloping Writing Skills: Wendy GoldupBayissa BekeleОценок пока нет

- STR - Write WaysДокумент11 страницSTR - Write WaysJerik Kalvin BertuldoОценок пока нет

- Learningdisorders2 190222054059Документ46 страницLearningdisorders2 190222054059Tiffany SagitaОценок пока нет

- Educ 95 Traditional Literacy 1STДокумент20 страницEduc 95 Traditional Literacy 1STJonathan GalanОценок пока нет

- PIIS0890856709633323Документ17 страницPIIS0890856709633323Jose Alonso Aguilar ValeraОценок пока нет

- Dislexia e EscritaДокумент40 страницDislexia e EscritaCarina BargueñoОценок пока нет

- ICTs in Assessment of Special Learning DifficultiesДокумент19 страницICTs in Assessment of Special Learning DifficultiesRubén Omar BarraganОценок пока нет

- 2018 - Lshss-Dyslc-18-0005 OkДокумент11 страниц2018 - Lshss-Dyslc-18-0005 OkAyundia Ruci Yulma PutriОценок пока нет

- Multiple Intelligence Theory As A Tool For Improving Student AchievementДокумент4 страницыMultiple Intelligence Theory As A Tool For Improving Student AchievementJoyce Ann UmbaoОценок пока нет

- Online AssignmentДокумент9 страницOnline AssignmentLakshmi JayakumarОценок пока нет

- Effective Instruction For Persisting Dyslexia in Upper Grades: Adding Hope Stories and Computer Coding To Explicit Literacy InstructionДокумент26 страницEffective Instruction For Persisting Dyslexia in Upper Grades: Adding Hope Stories and Computer Coding To Explicit Literacy InstructionPaul AsturbiarisОценок пока нет

- El Caso Contra El Neuropsicoanálisis IJPДокумент23 страницыEl Caso Contra El Neuropsicoanálisis IJPTio Alf EugenioОценок пока нет

- Juicio de RealidadДокумент10 страницJuicio de RealidadTio Alf EugenioОценок пока нет

- Estudios Sobre El Sistema Limbico en Niños y AdolescentesДокумент12 страницEstudios Sobre El Sistema Limbico en Niños y AdolescentesMedico ZaviОценок пока нет

- Lifetime Prevalence Mental Disorders 2010 Jaacap-2Документ10 страницLifetime Prevalence Mental Disorders 2010 Jaacap-2Tio Alf EugenioОценок пока нет

- Burden in Schizophrenia CaregiverДокумент13 страницBurden in Schizophrenia CaregiveryatzachОценок пока нет

- Maturation of The Limbic System Revealed by MR FLAIR ImagingДокумент5 страницMaturation of The Limbic System Revealed by MR FLAIR ImagingTio Alf EugenioОценок пока нет

- Lifetime Prevalence Mental Disorders 2010 Jaacap-2Документ10 страницLifetime Prevalence Mental Disorders 2010 Jaacap-2Tio Alf EugenioОценок пока нет

- The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy The Open Journal of Occupational TherapyДокумент17 страницThe Open Journal of Occupational Therapy The Open Journal of Occupational TherapyAlicia de la CalОценок пока нет

- DomeДокумент86 страницDomeSiti Nur Hafidzoh Omar100% (1)

- OT - Neonatal - Intensive - Care - IJOT - ENДокумент6 страницOT - Neonatal - Intensive - Care - IJOT - ENSara Gomes CastroОценок пока нет

- Multiple SclerosisДокумент6 страницMultiple SclerosisandrearuzziОценок пока нет

- The Test of Playfulness and Children With Physical DisabilitiesДокумент17 страницThe Test of Playfulness and Children With Physical DisabilitiesGeorgiana OghinciucОценок пока нет

- Sensory Rooms Autism Reference ListДокумент3 страницыSensory Rooms Autism Reference ListMiss MarijaОценок пока нет

- OT Serv in Psych and Social Aspects of MHДокумент19 страницOT Serv in Psych and Social Aspects of MHLydia MartínОценок пока нет

- Ot Resume PDFДокумент2 страницыOt Resume PDFapi-470089121Оценок пока нет

- Play Therapy: Activity PlanДокумент3 страницыPlay Therapy: Activity PlanPatrick MangilinОценок пока нет

- CH 9 Occupational Therapy FrameworkДокумент2 страницыCH 9 Occupational Therapy Frameworkapi-299934163Оценок пока нет

- Individual Education PlanДокумент9 страницIndividual Education PlanPenelopeОценок пока нет

- Pratheeba Balasubramaniyan's ResumeДокумент2 страницыPratheeba Balasubramaniyan's ResumeMakoba AnalyticsОценок пока нет

- Peds Soap NoteДокумент4 страницыPeds Soap Noteapi-488745276Оценок пока нет

- Early InterventionДокумент6 страницEarly InterventionDeepanshi TyagiОценок пока нет

- Gea1212 Assignment 2Документ3 страницыGea1212 Assignment 2Choto PunОценок пока нет

- Paez Resume CurrentДокумент3 страницыPaez Resume Currentapi-529194320Оценок пока нет

- Changes in ADL Dependence and Aspects of Usability Following Housing Adaptation-A Longitudinal PerspectiveДокумент9 страницChanges in ADL Dependence and Aspects of Usability Following Housing Adaptation-A Longitudinal PerspectiveWilmer Alexsander Pacherrez FernandezОценок пока нет

- Supporting Children With SEN An Introduction To A 3 Tiered School Based OT Model of Service Delivery in WFOT Bulletin 2017Документ11 страницSupporting Children With SEN An Introduction To A 3 Tiered School Based OT Model of Service Delivery in WFOT Bulletin 2017Shan Shan LuiОценок пока нет

- Mirror Therapy and Task-Oriented Training For PeopleДокумент8 страницMirror Therapy and Task-Oriented Training For PeopleEmilia LaudaniОценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of A Handwriting Readiness Program in Head Start: A Two-Group Controlled TrialДокумент9 страницEffectiveness of A Handwriting Readiness Program in Head Start: A Two-Group Controlled TrialLena CoradinhoОценок пока нет

- Calm and ConfidentДокумент12 страницCalm and Confidentapi-581007170Оценок пока нет

- Implementing Occupation-Based PracticeДокумент10 страницImplementing Occupation-Based Practiceapi-392268685Оценок пока нет

- Mckenna 2013Документ4 страницыMckenna 2013zettaknОценок пока нет

- Analice Mendel: Clinical Doctorate in Occupational Therapy GPA: 4.0Документ1 страницаAnalice Mendel: Clinical Doctorate in Occupational Therapy GPA: 4.0api-518311936Оценок пока нет

- A Grounded Theory Analysis of The Relationship Between Creativity and Occupational TherapyДокумент389 страницA Grounded Theory Analysis of The Relationship Between Creativity and Occupational TherapyAngela EnacheОценок пока нет

- Depression Children PDFДокумент2 страницыDepression Children PDFConstanzaОценок пока нет

- HEM 53 Timetable 2012 Ver 3Документ8 страницHEM 53 Timetable 2012 Ver 3Chema SaizОценок пока нет

- 110 326 1 PBДокумент23 страницы110 326 1 PBAnonymous h5idncz8Оценок пока нет

- 4 ModuloДокумент77 страниц4 Moduloantoniomariano1106Оценок пока нет

- Occupational Therapy CompetenciesДокумент2 страницыOccupational Therapy Competencieslolocy LОценок пока нет

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossОт EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (6)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОт EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОценок пока нет

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeОт EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityОт EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (24)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaОт EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (42)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedОт EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (80)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDОт EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Self-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!От EverandSelf-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsОт EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.От EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (110)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerОт EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (392)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityОт EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsОт EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (169)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryОт EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (44)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessОт EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (328)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsОт EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (3)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningОт EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (3)

- Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)От EverandGut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (378)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceОт EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (51)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlОт EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (58)