Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

5 Reducing Time To Analgesia in The Emergency Department Using A

Загружено:

MegaHandayaniОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

5 Reducing Time To Analgesia in The Emergency Department Using A

Загружено:

MegaHandayaniАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Copyright eContent Management Pty Ltd. Contemporary Nurse (2012) 43(1): 2937.

Reducing time to analgesia in the emergency department using a

nurse-initiated pain protocol: A before-and-after study

JUDITH C FINN*,+,!,#, AMANDA RAE**, NICK GIBSON*, ROGER SWIFT++, TAMARA WATTERS!!

AND IAN G JACOBS*,#

*Discipline of Emergency Medicine (M516), The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA,

Australia; +School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC,

Australia; !Centre for Nursing Research, Innovation and Quality, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital,

Nedlands, WA, Australia; #St John Ambulance (Western Australia), Belmont, WA, Australia; **Nickol

Bay Hospital, Karratha, WA, Australia; ++Emergency Department, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital,

Nedlands, WA, Australia; !!Fremantle Hospital and Health Service, Fremantle, WA, Australia

Abstract: Suboptimal management of pain in emergency departments (EDs) remains a problem, despite having been

rst described over two decades ago. A before-and-after intervention study (with a historical control) was undertaken in

one Western Australian tertiary hospital ED to test the effect of a nurse-initiated pain protocol (NIPP) intervention. A

total of 889 adult patients were included: 144 in the control group and 745 in the intervention group. Patients in the

intervention group were: More likely to have a pain score recorded than those in the control group; have reduced median

time to the rst pain score; and reduced time to analgesia. The statistically signicant reduction in both time to pain score

and time to analgesia remained, even when adjusted by age and sex. Whilst we demonstrated the safety and efcacy of a

NIPP in ED, an unacceptable proportion of patients continued to have inadequate pain relief.

Keywords: emergency nursing, pain relief

T here are over six million patient presenta-

tions to emergency departments (EDs)

in Australia each year (Australian Institute of

are assessed and triaged by an experienced ED

nurse, who allocates the patient to one of ve

Australasian triage scale (ATS) codes, reect-

Health and Welfare, 2006) of which pain is the ing that patients clinical urgency (Australasian

most frequent symptom; occurring in up to College for Emergency Medicine, 2006). The tri-

80% of all presentations (National Institute of age nurse is also in a position to initiate appropriate

Clinical Studies, 2004). For several decades there investigations or initial management, according

has been evidence of the physiological and psy- to organisational guidelines (Australasian College

chological adverse effects of acute (and chronic) for Emergency Medicine, 2006), although this

pain (Macintyre et al., 2010) and yet subopti- is less commonly undertaken. Despite the triage

mal management of pain remains a problem in nurse assessing pain, ED nurses do not routinely

EDs (Arendts & Fry, 2006; Karwowski-Soulie administer any analgesic medications until the

et al., 2006; Rupp & Delaney, 2004; Todd et al., patient has been assessed by the medical ofcer.

2007). A number of strategies have been pro- Depending on the workload of the ED, there can

posed to increase the timely administration of be considerable delay between the patients pre-

analgesic medications for ED patients, includ- sentation at ED and being seen by a doctor; and

ing nurse-initiated (NI) analgesia (Fosnocht & even longer until pain relief is actually adminis-

Swanson, 2007; Fry, Ryan, & Alexander, 2004; tered (Hoot & Aronsky, 2008).

Kelly, Brumby, & Barnes, 2005; Sando, Usher, We sought to introduce and evaluate the prac-

& Buettner, 2009). tice of nurse-initiated analgesia in the ED of

Nurse-initiated analgesia is dened as the ini- a busy tertiary hospital, whereby the ED triage

tiation of analgesia by nursing staff, using a pre- nurse (or other specically trained ED nurse)

dened protocol, prior to the patient being seen administered analgesic medications according to

by a medical ofcer (Kelly et al., 2005, p. 151). a pre-dened protocol, without the patient being

In Australia, all patients presenting to an ED rst assessed by a medical ofcer.

Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 CN 29

CN Judith C Finn et al.

METHODS chart depicting the decision path to be followed

A before-and-after study with a historical control and single page information sheets for each of the

(National Health and Medical Research Council, protocol medications. These information sheets

2009) was undertaken to test the null hypothesis described the drug, dosage, route of administra-

that the nurse-initiated pain protocol (NIPP) tion, indications, contraindications, potential

intervention had no effect on either the time to adverse effects, required documentation and

pain assessment or the time to analgesia. patient follow-up. Table 1 shows which medica-

The study was undertaken in the ED of an tions were to be administered depending on the

urban tertiary teaching hospital, in Perth, Western patients initial pain score. The opioid analgesics

Australia. In 2009, a total of 417,259 patients [oral oxycodone and intravenous (IV) morphine]

attended Perth metropolitan EDs, of which required medical approval prior to administration,

54,740 attended the study hospital ED. The whereas the other listed medications were nurse-

ED is medically staffed by a mix of consultant initiated. The NIPP emphasised the importance

emergency physicians, senior registrars, resident of pain assessment using the PAINED acronym,

medical ofcers and interns. The ED nurses are i.e., place, amount, intensiers, nulliers, effects

predominantly registered nurses, some of whom of analgesics and description. Pain scores were to

have completed a 12-month postgraduate emer- be recorded as soon as possible at triage, and again

gency nursing certicate. The triage nurse posi- 60 minutes after oral analgesia or 30 minutes after

tion is lled on a shift-by-shift basis by a senior oral oxycodone or IV morphine. Nurses were also

registered nurse. advised to consider non-pharmacological meth-

All adult patients (18 years) presenting to ods of pain relief, such as splinting, support or

the ED with pain, during the study period from cold packs.

4 April 2009 to 25 June 2009, were eligible for

recruitment into the intervention arm of the Education

study. Patients meeting the following conditions Prior to implementation of the NIPP, medical

were excluded: presented with chest pain of pre- and nursing staff were encouraged to attend infor-

sumed cardiac origin or with headache; were tri- mation sessions about the NIPP. Nurses were not

aged as emergency or urgent (Australasian Triage permitted to administer analgesia per the NIPP

Score 1 and 2; Australasian College for Emergency until they had undertaken specic training and

Medicine, 2006); exhibited unstable vital signs; had demonstrated competence. In addition, all

were pregnant or lactating; had known contra- medical staff were advised of their responsibilities

indications to one of the study drugs; declined regarding the administration of Schedule 8 drugs

analgesia; or already had an analgesia related man- by nurses (Department of Health and Ageing,

agement plan in place. 2010), phone ordering and written prescriptions.

Over the 12 months prior to the introduc- Hard copies of the summary protocol guidelines

tion of the NIPP, baseline data about initial pain were laminated and displayed in strategic areas

management in the ED had been collected as part such as the triage desk, transit area and other

of the (Australian) National Institute of Clinical common areas in the ED and complete protocol

Studies (NICS) National Emergency Care Pain details were led in the nursing practice guide-

Management Initiative (Yeoh & Huckson, 2007). lines sited in the general ED area and the clinical

These data were used as the convenience sample nurse educators ofce.

for the historical cohort, for comparison with the

prospectively collected intervention data. Outcomes

The primary outcomes were: (a) time to rst pain

Intervention score recorded; and (b) time to rst analgesia

The ED NIPP was developed in consultation administered. These were, respectively, dened as

with hospital medical, nursing and pharmacy the time interval difference between the patient

staff, resulting in guideline instructions, a ow arrival in the ED; and (a) the time of the rst pain

30 CN Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 eContent Management Pty Ltd

Reducing time to analgesia in the emergency department CN

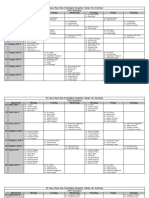

TABLE 1: ED NURSE-INITIATED ANALGESIA PROTOCOL ACCORDING TO INITIAL Any adverse events in the inter-

PAIN SCORE vention group were recorded.

Pain score Action

Data collection

Mild 2 paracetamol 500 mg (=1 g) Data were initially extracted from

13 or clinical records on a study-specic

3 paracetamol 500 mg tabs if patients estimated weight form and then entered into an Excel

is more than 100 kg

database that had been specically

or

developed for the project by one

2 ibuprofen 200 mg (=400 mg) if paracetamol is

contraindicated of the three study research nurses.

For further analgesia discuss with senior registrar Data collected included: patient

Moderate 2 paracetamol 500 mg/codeine 30 mg (Panadeine Forte) age, gender, data and time of ED

36 or presentation; triage category using

PO 3 ibuprofen 200 mg/codeine 12.8 mg (Nurofen Plus) the ATS (Australasian College for

For further analgesia discuss with senior registrar Emergency Medicine, 2006); time

Severe Patient to go through to ED assessment area ASAP, then and value of rst pain score; type

710 2 paracetamol 500 mg (=1 g) of analgesia self-administered by

PLUS 3 ibuprofen 200 mg (=600 mg) patient prior to ED presentation;

PLUS IV morphine 2.5 mg boluses up to 10 mg time and type of rst analgesic

or medication administered in ED;

If patient cannot proceed through to ED assessment area, and non-pharmacological pain

then management strategies used. ED

2 paracetamol 500 mg (=1 g) diagnosis was manually catego-

PLUS 3 ibuprofen 200 mg (=600 mg) rised into one of the International

PLUS 12 Endone 5 mg tabs (max 10 mg) Classication of Diseases (ICD-

For further analgesia discuss with senior registrar and get 10) Chapters (World Health

script for schedule 8 drugs

Organisation, 2007).

score recorded, and (b) the rst analgesic medica- Sample size and power

tion administered. A sample size calculation was performed prior

A verbal numeric rating scale (VNRS) from to the implementation phase of the NIPP using

010 was used to assess (and re-assess) pain, information gleaned from the N = 144 historical

where 0 represents no pain and 10 represents control group. With a baseline mean time to pain

worst pain imaginable. The VNRS has been score of 61.5 minutes and a standard deviation

shown to be a sensitive (and practical) measure (SD) of 56.3 minutes, a total of 144 cases in the

of acute pain in EDs (Holdgate, Asha, Craig, & intervention group would provide a power of 0.99

Thompson, 2003). Pain scores of 06 were con- to detect a 50% relative difference in mean time

sidered to be mild/moderate pain and pain scores to pain score between the experimental and con-

of 710 were classed as severe pain. trol arms of the study with a type 1 error of 0.05

For the initial severe pain cases who had both (Dupont & Plummer, 1990). However, the intent

an initial and post-analgesia pain score recorded, of the study was to trial the implementation of the

adequacy of analgesic effect was calculated as per NIPP intervention for up to 3 months and hence

Jao, McD Taylor, Taylor, Khan, and Chae (2011) the actual number of cases in the experimental

namely a reduction in the triage pain score of 2 group was much larger than the 144 required.

and to a level <4. The NICS denition of effec-

tive pain management, i.e., three-point or better Statistical analysis

reduction in severe pain scores, was also calculated Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the

(National Institute of Clinical Studies, 2008). data, including means with SD and medians with

eContent Management Pty Ltd Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 CN 31

CN Judith C Finn et al.

interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. RESULTS

Denominators for the calculation of percentages The study cohort comprised 889 patients (51%

varied because of missing values for some vari- males), with 144 in the pre-intervention (his-

ables, and in such cases the denominators used are torical sample) group and 745 post-intervention

reported. Comparisons between the before and group. Overall, most of the patients fell within

after groups were made using Pearsons Chi-squared ATS category 3 or 4 (see Table 2; ATS category

test for nominal/ordinal data and the t-test or the 1 and 2 were excluded) and two-thirds had an

non-parametric MannWhitney U-test for con- initial pain score of 06.Overall, 88.8% of

tinuous variables (depending on whether the data all cases attending ED for pain fell into four

met the assumptions of normality). Multivariable main diagnostic categories (based on ICD-10

regression (logistic/multiple regression depending Chapters; World Health Organisation, 2007),

on level of measurement of the outcome variable) namely: (1) disorders of the musculoskeletal sys-

was performed to adjust for potential confound- tem and connective tissue (60.4%); (2) disorders

ers, with results reported as odds ratios (OR) and of the digestive system (13.4%); (3) infectious

95% condence intervals (CI). Sub-group analysis and parasitic diseases (9.7%); and (4) disorders

by pain severity, i.e., mild/moderate pain (pain of the genitourinary system (5.3%). Of those

score 06) and severe

pain (pain score 710),

was dened a priori. For TABLE 2: DIFFERENCES IN BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PRE- AND

POST-INTERVENTION GROUPS

the analysis of time to

analgesia, only patients N PRE N = 144 N POST (N = 745) Difference

with a recorded initial

pain score of at least 1 Gender: male (%) 144 78 (54.2%) 745 380 (51%) 0.49a

b

were included. All analy- Age 144 740 0.38

ses were performed using Mean (SD) 38.9 (20.0) 41.9 (19.7)

IBM SPSS Statistics v19.0 Median 32.1 37.5

and statistical signicance ATS 144 744

was accepted as p < 0.05. 3 75 (52.1%) 349 (46.9%) 0.48a

4 66 (45.8%) 382 (51.3%)

Ethics approval 5 3 (2.1%) 13 (1.7%)

Ethics approval for this Musculoskeletal 144 103 (71.5%) 745 434 (58.3%) 0.003a

system related ED

study was obtained from diagnosis

the Hospitals Human Analgesia prior to 74 36 (48%) 745 180 (24.3%) <0.001a

Research Ethics Commit- ED presentation

tee, QIA#2226. Given yes (%)

that the intervention was Pain score 144 83 (57.6%) 745 708 (95%) <0.001a

recorded yes (%)

deemed to be a quality

Initial pain score 83 708 0.03b

improvement activity and

Mean (SD) 4.75 (3.2) 5.67 (2.4)

the data required for the

Median 5.00 6.00

study was already col-

Initial pain score 83 708 0.82b

lected as part of normal category N (%)

clinical practice, a waiver Mildmoderate 53 (63.9%) 443 (62.6%)

of consent was granted. (06)

The data collected were Severe (710) 30 (36.1%) 265 (37.4%)

initially identiable, but Non- 144 41 (28.5%) 745 90 (12.1%) <0.001a

only de-identied data pharmacological

pain interventions

were used for data manip-

ulation and analysis. a

Pearsons Chi-squared test; bMannWhitney U-test.

32 CN Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 eContent Management Pty Ltd

Reducing time to analgesia in the emergency department CN

patients in the diagnostic category of the mus- Adequacy of analgesic effect

culoskeletal system and connective tissue, 81% Only around 50% of patients overall had their

(435/537) were related to injury. The majority second pain score within 1 hour of administra-

of cases (76%) were recruited during the morn- tion of analgesia and this was no different when

ing and afternoon nursing shifts at ED, which only the severe pain group was considered. For

corresponded to the period when the research patients with an initial pain score of 710 (i.e.,

nurses were present. severe pain), and both an initial and post-anal-

As shown in Table 2, the two groups did not gesia pain score recorded (N = 238), a three-point

differ with respect to age, gender, ATS category or better reduction in pain score was achieved for

or initial pain score category. However, the his- a signicantly higher proportion of patients in

torical control group had a lower proportion the post-intervention group (115/216 = 53.2%)

of patients with a pain score recorded; a lower compared to the baseline period (4/22 = 18.2%;

median initial pain score; and a higher propor- 2 = 9.82, 1df, p = 0.003). Using the Jao et al.

tion of patients who received non-pharmacolog- (2011) denition of adequate analgesia pro-

ical pain relieving interventions. Patients in the duced similar (but not identical results), with

intervention group were much more likely to 2/22(9.1%) in the pre-intervention group and

have a pain score recorded than those in the con- 70/216 (32.4%) in the post-intervention group

trol group (95 vs. 58%, p < 0.001), even when achieving adequate analgesia (2 = 5.44, 1df,

adjusted for age and sex (OR = 13.9, 95% CI p = 0.03).

8.6, 22.4).

Adverse events (NIPP group only)

Primary outcomes Of the 548 (74%) of the NIPP patients who

The time to the rst pain score was reduced from received an analgesic medication in ED, 22 (4%)

a median of 47 (IQR 2093) minutes in the had an adverse event agged; 10 (45.5%) in the

control group to a median of less than 1 minute patients with mild/moderate pain (PS 06) and

(IQR 026) in the NIPP intervention group 12 (54.5%) in the severe pain group (PS 710).

(p < 0.001). The comparison of time to analgesia Only 15 of these events were described of

administration only included patients who had an these half as nausea and the other half as feel-

initial pain score of greater than or equal to 1, ing light headed/dizzy. The medications that

i.e., N = 67 in the control group and N = 689 in had been given in these 22 cases were as follows:

the intervention group. The time to analgesia in paracetamol (N = 7); paracetamol + codeine

the intervention group was signicantly reduced (N = 5); morphine (N = 4); ibuprofen (N = 3);

from a median of 98 (IQR 44137) minutes to oxycodone (N = 3). There were no serious adverse

28 (IQR 858) minutes (p < 0.001). The statisti- events recorded.

cally signicant reduction in both median time to

pain score and median time to analgesia remained, DISCUSSION

even when adjusted for age and sex. We demonstrated that a NIPP resulted in dra-

Both the time to initial pain score and the matic improvements in each of the indicators

time to analgesia administration were reduced in commonly used to gauge the quality of pain man-

the NIPP intervention group compared to the agement in EDs. When compared to a historical

pre-intervention group in both the mild/mod- control group, the NIPP patients were more likely

erate and severe pain sub-groups, as shown in to have an initial pain score recorded (95% vs.

Table 3. Patients in the NIPP group with severe 58%, p < 0.001); have a reduced median time to

pain were more likely to receive analgesia within initial pain score (<1 min vs. 47 min, p < 0.001)

30 minutes, as per the NICS recommendations and a reduced median time to rst analgesia (28

(National Institute of Clinical Studies, 2008), min vs. 98 min, p < 0.001). Whilst the adequacy

than patients in the control group (47.3% vs. of analgesic effect for patients with severe pain, as

20%, p = 0.009). dened by Jao et al. (2011), substantially increased

eContent Management Pty Ltd Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 CN 33

CN Judith C Finn et al.

TABLE 3: DIFFERENCES IN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY OUTCOMES PRE- AND POST-INTERVENTION, BY SEVERITY OF PAIN

N PRE (N = 53) N POST (N = 443) Difference

Initial pain score = 06 (N = 496)

Time to 1st pain score (min) 53 443 <0.001a

Range 0197 0289

Mean (SD) 55.6 (50.5) 20.9 (39.6)

Median (IQR) 43 (1488) 0 (027)

Time to analgesia (min)c 21 283 <0.001a

Range 0366 0315

Mean (SD) 108.4 (90) 44.2 (57.5)

Median (IQR) 88 (48.5152) 22 (564)

Initial pain score = 710 (N = 295)

PRE (N = 30) POST (N = 265) Difference

Time to 1st pain score (min) 30 <0.001a

Range 0259 264 0284

Mean (SD) 73.5 (65.0) 17.3 (35.9)

Median (IQR) 49 (25126) 0 (022)

Time to analgesia (min)c 25 <0.001a

Range 2386 220 0284

Mean (SD) 105.4 (85.9) 44.6 (46.4)

Median (IQR) 105 (43134) 32 (1356)

Analgesia within 30 min 25 5 (20.0%) 220 104 (47.4%) 0.009b

Three-point reduction 22 4(18.2%) 216 115 (53.2%) 0.003b

in pain scored

Adequate analgesic effectd,e 22 2(9.1%) 216 70 (32.4%) 0.02b

a

MannWhitney U-test; bPearsons Chi-squared test; cOnly patients with initial pain scores > 0; dOnly patients with initial

and post-analgesia pain scores; eAs dened by Jao et al. (2011)

in the NIPP group, there were still two-thirds of For example, a beforeafter study conducted

patients with inadequate pain relief. Thus we have in an urban university ED in Utah (USA;

shown that whilst NIPP can improve pain man- Fosnocht & Swanson, 2007), showed a reduction

agement in EDs, there is still scope for further in the mean time to pain medication administra-

improvement. tion from 76 to 40 minutes (p < 0.001) after the

Provision of effective pain management in introduction of a triage pain protocol initiated

EDs requires systems to ensure adequate assess- by nurses, for patients presenting with isolated

ment of pain, provision of timely and appro- extremity or back pain. However, individual ED

priate analgesia, with frequent monitoring and nurse compliance with the pain protocol varied

reassessment of pain (Macintyre et al., 2010). between 896% and the protocol was not used

Enabling an ED nurse to assess a patients pain in 30% of the eligible 800 patients (Fosnocht &

at the point of presentation to ED and then Swanson, 2007). At a Swedish university hos-

administer analgesia according to a pre-approved pital ED, Muntlin, Carlsson, Sfwenberg, and

protocol simply makes sense, given the goal to Gunningberg (2011) implemented a NI intra-

reduce time to analgesia. The evidence for the venous analgesic protocol (IV morphine) for

efcacy of NI analgesia in EDs is persuasive, abdominal pain, and measured time to analge-

albeit mostly based on before and after studies, sia at three time points: before (A1); during (B);

in single centres. and after (A2) the intervention. The mean time

34 CN Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 eContent Management Pty Ltd

Reducing time to analgesia in the emergency department CN

to analgesia was reduced from 2.5 hours (A1) These crude estimates of protocol adherence

to 1.3 hours (B), but reverted back to 2.1 hours are consistent with results reported elsewhere. In

during the A2 phase, highlighting the challenges a recent study (Stephan et al., 2010) conducted

in sustaining changes in clinical practice. in a university hospital in Switzerland it was

In Australia, it has been shown that NI anal- found that their locally developed pain manage-

gesia is safe and efcacious (Fry & Holdgate, ment protocol for ED was only correctly applied

2002; Kelly et al., 2005). A decade ago, at a uni- in 42% of patients, with the protocol incorrectly

versity teaching hospital in Sydney (Australia), or only partially applied in 30% of patients and

Fry and Holdgate (2002) demonstrated that an 28% of patients refused any analgesia at the

IV morphine pain protocol could be safely and time of presentation. Similarly, in a study of

effectively implemented in the ED for patients NI oral paracetamol for ED patients present-

with acute severe pain. The median time from ing with minor musculoskeletal injury at a uni-

triage to administration of NI morphine (time versity hospital in Hong Kong, whilst the mean

to narcotic) was 18 minutes. Whilst there was time to analgesia in the NI-Paracetamol group

no concurrent comparison group, a previous was dramatically reduced compared to the non

audit at the same hospital had found median NI-Paracetamol groups (9 min vs. 93 min) and

time of 58 minutes between triage and admin- pain scores were signicantly lower at 60 minutes,

istration of analgesia (Fry, Holdgate, Baird, Silk, only 22% of eligible patients actually received

& Ahern, 1999). Similarly, Kelly et al. (2005) in paracetamol by the triage nurse (Wong, Chan,

an urban public teaching hospital in Melbourne Rainer, & Ying, 2007). As astutely concluded by

(Australia), showed that specially trained and cre- the authors protocols and standing orders offer

dentialed ED nurses could safely and effectively options for nurses, however, the translation of the

initiate and manage titrated IV opioid analgesia concept into clinical reality is multidimensional

for selected painful conditions. Unfortunately and highly complex (Wong et al., 2007, p. 69).

the study was suspended early when an exter- In our study, anecdotal feedback indicated

nal government body apparently challenged the that NIPP implementation was less likely when

legality of what they perceived to be nurse pre- the ED was busy or when no research nurse was

scribing (Kelly et al., 2005). That this should present in ED. Moreover, we were aware that

occur is fascinating, given that out-of-hospital there were some triage nurses who refused to par-

paramedic practice around the world relies on ticipate in the study. We did not formally survey

non-physicians administering analgesia (and a the staff (or patients) re their experiences/attitudes

suite of other medications) on the basis of pre- about NIPP, which on reection was an unfortu-

approved protocols. nate omission. As identied by Fry, Bennetts, and

Because medication dosage was not reliably Huckson (2011, p. 273), further investigation is

entered into the study database, our capacity to needed into emergency nurses attitudes towards

ascertain compliance with the protocol was lim- the enablers and barriers to NI policies.

ited. However we were able to report that the type

of analgesic medication(s) administered was con- LIMITATIONS

sistent with the NIPP for the specic pain score This was a single centre study, based on a non-

in 61.1% of patients who received an analgesic consecutive convenience sample of patients. As

agent. This congruence with the protocol was such the results may not be generalisable to other

higher for patients with mildmoderate pain than EDs with different stafng proles and/or case-

for patients with severe pain (83.4 vs. 30.6%). mix. The data for the pre-intervention historical

One might assume that patients with severe pain cohort that was used as the comparison group

were more likely to have been assessed by an ED were collected as part of an audit process, up to

physician and have had their pain management 1 year prior to the intervention study. It is there-

individually adjusted, although this was not cap- fore not surprising that differences between the

tured in the database. groups were identied, thereby increasing the risk

eContent Management Pty Ltd Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 CN 35

CN Judith C Finn et al.

of confounding of the result. However, adjust- REFERENCES

ment for potential confounders through the use Arendts, G., & Fry, M. (2006). Factors associated with

of multivariable statistics did not alter the strong delay to opiate analgesia in emergency departments.

effect of the NIPP on time to initial pain score The Journal of Pain, 7(9), 682686.

and time to analgesia. Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. (2006).

P06 policy on the Australasian triage scale. Retrieved

Despite the study inclusion criteria being

from http://www.acem.org.au/media/policies_and_

patients presenting to ED with pain, a small guidelines/P06_Aust_Triage_Scale_-_Nov_2000.pdf

number of patients (3.9% overall) had an ini- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2006).

tial pain score recorded as 0. This could mean Australian hospital statistics 200405. AIHW health

that these patients were incorrectly included in services series (Vol. AIHW Cat no. HSE41 No 26).

the study, or it could indicate that patients can Canberra, ACT: Author.

still nominate their initial pain score as 0 even Department of Health and Ageing. (2010). Poisons

if their reason for presenting to ED is related to standard 2010: F2010L02386. Retrieved from http://

pain (for instance, patients with pain on move- www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2010L02386

ment but no pain at rest). We were not able to Dupont, W. D., & Plummer, W. D., Jr. (1990).

discern which of these alternatives applied. There Power and sample size calculations: A review and

computer program. Controlled Clinical Trials, 11(2),

were also 11% (N = 98/889) of cases without a

116128.

recorded initial pain score. It cannot be certain Fosnocht, D. E., & Swanson, E. R. (2007). Use of a tri-

whether this reects pain not being assessed or age pain protocol in the ED. The American Journal of

simply not recorded. Emergency Medicine, 25(7), 791793.

Fry, M., Bennetts, S., & Huckson, S. (2011). An

CONCLUSION Australian audit of ED pain management patterns.

This study has demonstrated that a NIPP in the Journal of Emergency Nursing, 27(3), 269274.

ED increased the likelihood of pain scores being Fry, M., & Holdgate, A. (2002). Nurse-initiated

recorded, reduced the time from ED presen- intravenous morphine in the emergency depart-

tation to the initial pain score and reduced the ment: Efficacy, rate of adverse events and impact

time to analgesia. Whilst the adequacy of analge- on time to analgesia. Emergency Medicine 14(3),

sic effect more than tripled, almost two-thirds of 249254.

all patients still had inadequate pain relief. Thus Fry, M., Holdgate, A., Baird, L., Silk, J., & Ahern, M.

(1999). An emergency departments analysis of pain

whilst we have demonstrated the potential ef-

management patterns. Australian Emergency Nursing

cacy of a NIPP, a system-wide multidisciplinary Journal, 2(1), 3136.

approach is likely to be required to address the Fry, M., Ryan, J., & Alexander, N. (2004). A prospective

persistent problem of oligoanalgesia (Wilson & study of nurse initiated Panadeine Forte: Expanding

Pendleton, 1989) in the ED. pain management in the ED. Accident and Emergency

Nursing, 12(3), 136140.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Holdgate, A., Asha, S., Craig, J., & Thompson, J.

This study was funded by a research grant from (2003). Comparison of a verbal numeric rating

The Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Research scale with the visual analogue scale for the measure-

Advisory Committee. The research team ment of acute pain. Emergency Medicine, 15(56),

acknowledges this nancial and other support 441446.

provided by the nursing and medical staff of Hoot, N. R., & Aronsky, D. (2008). Systematic review

of emergency department crowding: causes, effects,

the emergency department. In particular, we

and solutions. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 52(2),

acknowledge and thank the following research 126136.

nurses for their assistance with implementation of Jao, K., McD Taylor, D., Taylor, S. E., Khan, M., &

the protocol and data collection: Grainne Mallen, Chae, J. (2011). Simple clinical targets associated

Susan Greyling and Michelle Lucking. Australian with a high level of patient satisfaction with their pain

New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry number: management. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 23(2),

ACTRN12611000953932. 195201.

36 CN Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 eContent Management Pty Ltd

Reducing time to analgesia in the emergency department CN

Karwowski-Soulie, F., Lessenot-Tcherny, S., Lamarche- Sando, J. J., Usher, K., & Buettner, P. (2009).

Vadel, A., Bineau, S., Ginsburg, C., Meyniard, O., Nurse-initiated narcotics: Their role in optimum

Brunet, F. (2006). Pain in an emergency department: patient management. Australasian Emergency Nursing

An audit. European Journal of Emergency Medicine, Journal, 12(4), 155155.

13(4), 218224. Stephan, F. P., Nickel, C. H., Martin, J. S., Grether,

Kelly, A. M., Brumby, C., & Barnes, C. (2005). Nurse- D., Delport-Lehnen, K., & Bingisser, R. (2010).

initiated, titrated intravenous opioid analgesia reduces Pain in the emergency department: Adherence to

time to analgesia for selected painful conditions. an implemented treatment protocol. Swiss Medical

Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7(3), 149154. Weekly, 140(2324), 341347.

Macintyre, P. E., Schug, S. A., Scott, D. A., Visser, E. J., Todd, K. H., Ducharme, J., Choiniere, M., Crandall,

Walker, S. M., & APM:SE Working Group of the C. S., Fosnocht, D. E., Homel, P., & Tanabe, P.

Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (2007). Pain in the emergency department: Results

and Faculty of Pain Medicine. (2010). Acute pain of the pain and emergency medicine initiative

management scientic evidence (3rd ed.). Retrieved (PEMI) multicenter study. The Journal of Pain,

from http://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/books-and- 8(6), 460466.

publications/acutepain.pdf Wilson, J. E., & Pendleton, J. M. (1989). Oligoanalgesia

Muntlin, ., Carlsson, M., Sfwenberg, U., & in the emergency department. American Journal of

Gunningberg, L. (2011). Outcomes of a nurse-initiated Emergency Medicine, 7(6), 620623.

intravenous analgesic protocol for abdominal pain in Wong, E. M. L., Chan, H. M. S., Rainer, T. H., &

an emergency department: A quasi-experimental study. Ying, C. S. (2007). The effect of a triage pain

International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(1), 1323. management protocol for minor musculoskel-

National Health and Medical Research Council. etal injury patients in a Hong Kong emergency

(2009). NHMRC levels of evidence and grades for department. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal,

recommendations for developers of guidelines. Retrieved 10(2), 6472.

from http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_les_nhmrc/le/ World Health Organisation. (2007). International statisti-

guidelines/evidence_statement_form.pdf cal classication of diseases and related health problems:

National Institute of Clinical Studies. (2004). 10th revision. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/

National emergency department collaborative report. classications/apps/icd/icd10online/

Melbourne, VIC: National Heath and Medical Yeoh, M., & Huckson, S. (2007). Audit of pain

Research Council. management in Australian emergency departments.

National Institute of Clinical Studies. (2008). National NICS national emergency care pain management

emergency care pain management initiative: Hospital initiative. Retrieved from http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_

information pack (pp. 112). Canberra, ACT: les_nhmrc/le/nics/programs/NICS%20EC%20

National Heath and Medical Research Council. CoP%20Pain%20Management%20Audit%20

Rupp, T., & Delaney, K. A. (2004). Inadequate analgesia ACEM%20Report%202007.pdf

in emergency medicine. Annals of Emergency

Medicine, 43(4), 494503. Received 09 April 2012 Accepted 17 August 2012

ANNOUNCING

Cross-cultural pedagogies: The interface between Islamic and Western

pedagogies and epistemologies

A special issue of International Journal of Pedagogies & Learning Volume 7 Issue 3 112 pages December 2012

Guest Editors: Ibrahima Diallo (University of South Australia) and

Shirley ONeill (University of Southern Queensland)

Cross-cultural pedagogies and teaching focusing on Islamic pedagogies and epistemologies in a western context and

the transfer of western pedagogies and epistemologies within an Islamic setting.

http://jpl.e-contentmanagement.com/archives/vol/7/issue/3/marketing/

eContent Management Pty Ltd, Innovation Centre Sunshine Coast, 90 Sippy Downs Drive,

Unit IC 1.20, SIPPY DOWNS, QLD 4556, Australia; Tel.: +61-7-5430-2290; Fax. +61-7-5430-2299;

services@e-contentmanagement.com www.e-contentmanagement.com

eContent Management Pty Ltd Volume 43, Issue 1, December 2012 CN 37

Copyright of Contemporary Nurse: A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession is the property of eContent

Management Pty. Ltd. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv

without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email

articles for individual use.

Вам также может понравиться

- The COAT & Review Approach: How to recognise and manage unwell patientsОт EverandThe COAT & Review Approach: How to recognise and manage unwell patientsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Define Medical Audit. Describe The Conditions, Prerequisites & Steps For Conducting Medical Audit in A General HospitalДокумент15 страницDefine Medical Audit. Describe The Conditions, Prerequisites & Steps For Conducting Medical Audit in A General HospitalAbdul RahamanОценок пока нет

- NABH IntroductionДокумент12 страницNABH IntroductionKrishna100% (1)

- Hospital DepartmentsДокумент16 страницHospital DepartmentsfictoriaОценок пока нет

- Activities Patient SafetyДокумент13 страницActivities Patient SafetyummuawisyОценок пока нет

- Clinical Establishment Act Standards For Hospital (LEVEL 3)Документ36 страницClinical Establishment Act Standards For Hospital (LEVEL 3)bksubrat100% (3)

- Prospectus of Paramedical College in Delhi - IPHIДокумент16 страницProspectus of Paramedical College in Delhi - IPHIParamedical CollegeinDelhiОценок пока нет

- PRE ANAESTHETIC ASSESSMENT New 1Документ41 страницаPRE ANAESTHETIC ASSESSMENT New 1lokeswara reddyОценок пока нет

- Obstetric HDU and ICU: Guidelines ForДокумент52 страницыObstetric HDU and ICU: Guidelines ForsidharthОценок пока нет

- TransitionДокумент13 страницTransitionDonna NituraОценок пока нет

- NABH IntroductionДокумент9 страницNABH IntroductionKrishnaОценок пока нет

- Stroke Clinical PathwayДокумент1 страницаStroke Clinical PathwayKanoknun PisitpatcaragulОценок пока нет

- Emergency NursingДокумент15 страницEmergency NursingAshley Ishika100% (1)

- Preoperative Assessment PolicyДокумент10 страницPreoperative Assessment PolicymandayogОценок пока нет

- Recovery Room Transfer Sheet44Документ1 страницаRecovery Room Transfer Sheet44Dr. Sumit Kumbhar0% (1)

- Western Australian Patient Identification Policy PDFДокумент14 страницWestern Australian Patient Identification Policy PDFpuspadiniaОценок пока нет

- 100 Bedded Hospital LectureДокумент53 страницы100 Bedded Hospital LectureIngyin KhinОценок пока нет

- Central Triage ProtocolДокумент1 страницаCentral Triage Protocolgechworkneh38Оценок пока нет

- MS ByLaws 2018Документ53 страницыMS ByLaws 2018محمد عقيليОценок пока нет

- Inpatient DepartmentДокумент7 страницInpatient Departmentshah007zaadОценок пока нет

- Australian Model Triage ScaleДокумент3 страницыAustralian Model Triage ScaleHendraDarmawanОценок пока нет

- Antimicrobial Prescribing PolicyДокумент20 страницAntimicrobial Prescribing PolicycraОценок пока нет

- Clinical Casuality ManagementДокумент6 страницClinical Casuality ManagementswathiprasadОценок пока нет

- Missing Patients ProcedureДокумент16 страницMissing Patients ProcedureAgnieszka WaligóraОценок пока нет

- CLCGP030 Theatre Operating List Session Scheduling PolicyДокумент19 страницCLCGP030 Theatre Operating List Session Scheduling PolicyJeffy PuruggananОценок пока нет

- Perioperative Scope of ServicesДокумент2 страницыPerioperative Scope of Servicesmonir61Оценок пока нет

- Vital Signs and Early Warning ScoresДокумент47 страницVital Signs and Early Warning Scoresdr_nadheem100% (1)

- 2007 International Patient Safety GoalsДокумент1 страница2007 International Patient Safety GoalsElias Baraket FreijyОценок пока нет

- Hospital GuidelinesДокумент236 страницHospital GuidelinesMheanne Romano100% (1)

- Ms-001 (2) Clinical Privi Form Anesthesia 2019Документ4 страницыMs-001 (2) Clinical Privi Form Anesthesia 2019Athira Rajan100% (1)

- Principles of Oncology and Outline of ManagementДокумент78 страницPrinciples of Oncology and Outline of ManagementPavan JonnadaОценок пока нет

- Assessment and Re-Assessment of Patients According To The Scope of ServiceДокумент9 страницAssessment and Re-Assessment of Patients According To The Scope of Servicegiya nursingОценок пока нет

- 6 Opening Presentation - NABH-2020Документ29 страниц6 Opening Presentation - NABH-2020priyaОценок пока нет

- TRIAGE POLICIES JuvyДокумент6 страницTRIAGE POLICIES JuvyCuyapo Infirmary Lying-In HospitalОценок пока нет

- Model Case RecordДокумент30 страницModel Case RecordAniruddha JoshiОценок пока нет

- New MRD Manual 12-1-15Документ12 страницNew MRD Manual 12-1-15aarti Hinge100% (1)

- Eye Care Centre - Best Eye Hospital in India - Shroff Eye CentreДокумент19 страницEye Care Centre - Best Eye Hospital in India - Shroff Eye CentreShroff Eye Centre - Eye hospitalОценок пока нет

- Operation Theater 1Документ24 страницыOperation Theater 1Susmita BeheraОценок пока нет

- Kpi Wards 2021 - A WingДокумент48 страницKpi Wards 2021 - A WingPriya LaddhaОценок пока нет

- PH 3.2 Prescription AuditДокумент3 страницыPH 3.2 Prescription AuditashokОценок пока нет

- How To Move The Patient From The Bed To The Wheelchair How To Move The Patient From The Bed To The WheelchairДокумент9 страницHow To Move The Patient From The Bed To The Wheelchair How To Move The Patient From The Bed To The WheelchairAfniy ApriliaОценок пока нет

- Hourly Round ProjectДокумент8 страницHourly Round ProjectaustinisaacОценок пока нет

- Accomplishment Report 2017 - IcuДокумент5 страницAccomplishment Report 2017 - IcuMikhaelEarlSantosTacordaОценок пока нет

- RSI For Nurses ICUДокумент107 страницRSI For Nurses ICUAshraf HusseinОценок пока нет

- A P Policy & Procedure: Ntibiotic OlicyДокумент24 страницыA P Policy & Procedure: Ntibiotic Olicyvijay kumarОценок пока нет

- Sri Guru Ram Das Charitable Hospital, Vallah, Sri Amritsar OPD ScheduleДокумент3 страницыSri Guru Ram Das Charitable Hospital, Vallah, Sri Amritsar OPD ScheduleTarlochan SinghОценок пока нет

- AirWay Management FinalДокумент54 страницыAirWay Management FinalagatakassaОценок пока нет

- New MRD PresentationДокумент40 страницNew MRD PresentationBAHHEP BAHHEPОценок пока нет

- MRDДокумент17 страницMRDPrasoon BanerjeeОценок пока нет

- Disaster MGMTДокумент72 страницыDisaster MGMTVarinder PalОценок пока нет

- JCI Standards Interpretation - June12004Документ18 страницJCI Standards Interpretation - June12004Niharika SharmaОценок пока нет

- Manual For EndosДокумент19 страницManual For EndosVarsha MalikОценок пока нет

- Manejo de Las Crisis en Anestesia - Gaba 2 Ed PDFДокумент424 страницыManejo de Las Crisis en Anestesia - Gaba 2 Ed PDFdianisssuxОценок пока нет

- Autoclave GuideДокумент48 страницAutoclave GuideIman 111Оценок пока нет

- Arero Primary Hospital Triage ProtocolДокумент4 страницыArero Primary Hospital Triage Protocolsami ketemaОценок пока нет

- Hospital Profile PDFДокумент29 страницHospital Profile PDFAnonymous BBdD0c100% (1)

- Initial Patient Assessment in OpdДокумент4 страницыInitial Patient Assessment in OpdLokender Goyal100% (1)

- Improving Operating Theatre Performance Complete Step Guide Without PicДокумент83 страницыImproving Operating Theatre Performance Complete Step Guide Without PicNana AkwaboahОценок пока нет

- PacuДокумент93 страницыPacunorhafizahstoh89Оценок пока нет

- Recycler View AdapterДокумент6 страницRecycler View AdapterMegaHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Dokumentasi CRUD BarangДокумент15 страницDokumentasi CRUD BarangMegaHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Desain Network - Ni Kade Mega Handayani - 1605551030Документ3 страницыDesain Network - Ni Kade Mega Handayani - 1605551030MegaHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Latihan Berjlan Dan Kelelahan KankerДокумент10 страницLatihan Berjlan Dan Kelelahan KankerMegaHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Jcs 4 125Документ10 страницJcs 4 125MegaHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Side Lying Potition and VentilatorДокумент8 страницSide Lying Potition and VentilatorMegaHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Contracted Pelvis by KABERA ReneДокумент14 страницContracted Pelvis by KABERA ReneKABERA RENEОценок пока нет

- Experience of Health Professionals Around An Exorcism: A Case ReportДокумент4 страницыExperience of Health Professionals Around An Exorcism: A Case ReportsorinfОценок пока нет

- Review Process of Discharge Planning: by Janet BowenДокумент11 страницReview Process of Discharge Planning: by Janet BowenAfiatur RohimahОценок пока нет

- All India Network Hospitals GeneralДокумент630 страницAll India Network Hospitals GeneralPankajОценок пока нет

- Reading and Writing Module 1Документ29 страницReading and Writing Module 1Billie Joys OdoganОценок пока нет

- Finally - A Complete Omega 3 Supplement, Only From GNLD!Документ2 страницыFinally - A Complete Omega 3 Supplement, Only From GNLD!Nishit KotakОценок пока нет

- Ashta Sthana ParikshaДокумент35 страницAshta Sthana ParikshaSwanand Avinash JoshiОценок пока нет

- Future of The Pharmaceutical Industry in The GCC 2017 PDFДокумент3 страницыFuture of The Pharmaceutical Industry in The GCC 2017 PDFJeet MehtaОценок пока нет

- Breastfeeding ManagementДокумент12 страницBreastfeeding ManagementtitisОценок пока нет

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and DiagnosisДокумент9 страницPosttraumatic Stress Disorder Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosisisa_horejsОценок пока нет

- Product Monograph of TelmisartanДокумент8 страницProduct Monograph of Telmisartandini hanifaОценок пока нет

- Therapeutic Encounter and Health History MelissaДокумент7 страницTherapeutic Encounter and Health History Melissaapi-313199824Оценок пока нет

- New Visionaries Ed PlanДокумент37 страницNew Visionaries Ed PlanSydney PaulОценок пока нет

- Learning Objectives:: Read and Study The Message of The Poem. Answer The Questions Given BelowДокумент6 страницLearning Objectives:: Read and Study The Message of The Poem. Answer The Questions Given BelowOLIVER DE RAMAОценок пока нет

- People As ResourceДокумент9 страницPeople As ResourceArup Dey100% (1)

- Renal Calculi Concept Map PathophysiologyДокумент3 страницыRenal Calculi Concept Map PathophysiologySharon TanveerОценок пока нет

- 2016 Baltimore's Very Important PeopleДокумент20 страниц2016 Baltimore's Very Important PeopleMichael DuntzОценок пока нет

- Blood Pressure Variability: How To Deal?: NR Rau, Gurukanth RaoДокумент5 страницBlood Pressure Variability: How To Deal?: NR Rau, Gurukanth RaoRully SyahrizalОценок пока нет

- Infection Control Measures in Dental Clinics in Kingdom of Saudi ArabiaДокумент4 страницыInfection Control Measures in Dental Clinics in Kingdom of Saudi Arabiaاحمد القحطانيОценок пока нет

- Vaughn Ramjattan: Cell: 354-7892 EmailДокумент5 страницVaughn Ramjattan: Cell: 354-7892 Emailvaughn ramjattanОценок пока нет

- GDS - Goldberg's Depression ScaleДокумент2 страницыGDS - Goldberg's Depression ScaleAnton Henry Miaga100% (1)

- Journal Reading PostpartumДокумент10 страницJournal Reading PostpartumNovie GarillosОценок пока нет

- 11 Strategies To Fight CancerДокумент73 страницы11 Strategies To Fight CancerPayal Nandwana100% (1)

- Cancer Bathinda's Dubious DistinctionДокумент2 страницыCancer Bathinda's Dubious DistinctionPardeepSinghОценок пока нет

- Hungry PlanetДокумент1 страницаHungry Planetpatricia pillarОценок пока нет

- Tor WFP Food Assistance For Assets ProjectДокумент15 страницTor WFP Food Assistance For Assets Projectsabri HanshiОценок пока нет

- Healthy Neighborhoods GuidebookДокумент102 страницыHealthy Neighborhoods GuidebookSuci Dika UtariОценок пока нет

- Tooth EruptionДокумент6 страницTooth EruptionDr.RajeshAduriОценок пока нет

- 8 GCP R2 ICH TraduccionДокумент78 страниц8 GCP R2 ICH TraduccionGuillermo PocoviОценок пока нет

- Dra. Michel Fernanda Girón Luna Cirujano DentistaДокумент2 страницыDra. Michel Fernanda Girón Luna Cirujano DentistaMichelle GirónОценок пока нет