Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Community Acquired Pneumonia

Загружено:

Daniel Puentes SánchezАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Community Acquired Pneumonia

Загружено:

Daniel Puentes SánchezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Annals of Internal Medicine

In the Clinic

Community-Acquired

Pneumonia Prevention

C

ommunity-acquired pneumonia (CAP) can

vary from a mild outpatient illness to a more Diagnosis

severe disease requiring hospital admission

and, at times, intensive care. CAP is the eighth lead-

ing cause of death, along with inuenza, and is the Treatment

leading cause of death from infectious diseases in

persons in the United States older than 65 years. The

key management decisions related to CAP are rec- Patient Information

ognition and treatment in a timely and effective

manner, dening the appropriate site of care (home,

hospital, or intensive care unit [ICU]), and ensuring

effective prevention. Health careassociated pneu-

monia (HCAP), or pneumonia in persons in contact

with such health care environments as nursing

homes and chronic hemodialysis centers or persons

recently discharged from the hospital, can be

caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms.

Whether HCAP is best classied as a form of

community-acquired or hospital-acquired pneumo-

nia is controversial.

The CME quiz is available at www.annals.org/intheclinic.aspx. Complete the quiz to earn up to 1.5 CME

credits.

Physician Writer CME Objective: To review current evidence for prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and practice

Michael S. Niederman, MD improvement of community-acquired pneumonia.

Funding Source: American College of Physicians.

Disclosures: Dr. Niederman, ACP Contributing Author, reports personal fees from Pzer,

personal fees from Thermo Fisher Scientic, grants and personal fees from Merck/Bayer, and

personal fees from Cempra outside the submitted work.

In the Clinic does not necessarily represent ofcial ACP clinical policy. For ACP clinical

guidelines, please go to https://www.acponline.org/clinical_information/guidelines/.

With the assistance of additional physician writers, the editors of Annals of Internal Medicine

develop In the Clinic using MKSAP and other resources of the American College of Physicians.

2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

Prevention

Who is at increased risk for age, with a special effort to re-

CAP? view risk factors in persons older

Persons with comorbid illness than 50 years. High-risk individu-

and the elderly are at increased als who should be vaccinated

risk for pneumonia and for hav- include persons living in special

ing a more complex course. In environments (long-term care

2006, there were nearly 1.3 mil- facilities), Alaskan natives or

lion hospitalizations for pneumo- American Indians, and/or those

nia in the United States, and 57% who have any of the following

were in persons older than 65 conditions: chronic heart disease

years (1). Comorbid illnesses that (congestive heart failure, cardio-

are associated with an increased myopathy but not hypertension),

incidence of CAP include respira- chronic lung disease (COPD but

tory disease, such as chronic ob- not asthma), diabetes mellitus,

structive pulmonary disease alcoholism, chronic liver disease,

(COPD); cardiovascular disease; cigarette smoking, cerebrospinal

diabetes mellitus; and chronic uid leaks, cochlear implants,

liver disease. Other at-risk popu- functional or anatomical asplenia

lations include those with HIV (including sickle cell disease),

infection and other forms of im- and immune-suppressing condi-

mune suppression, as well as tions (including HIV infection;

persons who have chronic kidney congenital or acquired immune

disease and those who have had deciencies; chronic renal failure;

splenectomy. nephrotic syndrome; other im-

mune suppression, including re-

Cigarette smoking and alcohol ceipt of long-term corticoste-

abuse also often result in severe roids; and cancer, including

forms of CAP. Cigarette smoking multiple myeloma, leukemia,

is a risk factor for bacteremic lymphoma, and Hodgkin

pneumococcal infection (2). disease).

Other common illnesses in per-

sons with CAP include cancer The 13-valent conjugate vaccine

and any neurologic illness that (PCV-13) and the 23-valent poly-

predisposes to aspiration, includ- saccharide vaccine (PPS-23) are

ing seizures. Immunization with the 2 licensed adult pneumococ-

pneumococcal vaccine in high- cal vaccines available. All adults

risk individuals and with inuenza should receive PCV-13 in series

vaccine in at-risk patients during with PPS-23. However, the timing

inuenza season is benecial for of immunization varies by age

preventing CAP and many of its and the presence of high-risk

complications. conditions. Because PCV-13 is

more immunogenic, it should

Who should receive pneumo- generally be given rst, when

coccal vaccination and when vaccination is indicated, to all

should they receive it? individuals who were not previ-

All individuals aged 65 years and ously immunized, and followed

1. American Lung Associa-

tion. Trends in pneumonia older and other high-risk persons 6 12 months later by PPS-23 (to

and inuenza and pneu- should receive pneumococcal add additional strain coverage).

monia morbidity and

mortality; 2010. vaccination. For persons without Immune-compromised patients

2. Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Farley

MM, et al. Cigarette smok-

high-risk conditions, vaccination younger than 65 years should

ing and invasive pneumo- should be given at age 65 years. receive PPS-23 only 8 weeks after

coccal disease. Active

Bacterial Core Surveillance Patients with risk factors should PCV-13. Persons who have previ-

Team. N Engl J Med. be vaccinated when the risk is ously received PPS-23 should

2000;342:681-9. [PMID:

10706897] rst identied, irrespective of receive a dose of PCV-13 at least

2015 American College of Physicians ITC2 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 October 2015

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

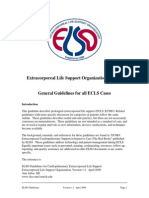

Figure. Recommended pneumococcal vaccine schedule and intervals, by age, health condition, and other risks.

No health condition Chronic Smoker or Immunocompromising Anatomical or Cerebrospinal fluid

or other risk health resident of condition functional asplenia leak or cochlear

condition* long-term implant

care facility

PCV13 PCV13

8 weeks

8 weeks

PPSV23 PPSV23

Adults aged

5 years

1964 years

1 year 5 years PPSV23

Adults aged

65 years

PCV13 5 years

612 months

PPSV23

The dashed line represents the interval between the two PPSV23 doses. PCV13# = 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PPSV23# =

23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

* Immunocompromising conditions are dened as congenital or acquired immunodeciency (including B- or T-lymphocyte deciency, com-

plement deciencies, and phagocytic disorders excluding chronic granulomatous disease), HIV infection, chronic renal failure, nephrotic

syndrome, leukemia, lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, generalized malignancy, multiple myeloma, solid organ transplant, and iatrogenic immu-

nosuppression (including long-term systemic corticosteroids and radiation therapy).

Anatomical or functional asplenia is dened as sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies, congenital or acquired asplenia, splenic

dysfunction, and splenectomy.

Chronic health conditions are dened as chronic heart disease (including congestive heart failure and cardiomyopathies, excluding hyper-

tension), chronic lung disease (including chronic obstructive lung disease, emphysema, and asthma), chronic liver disease (including cirrhosis),

chronic alcoholism, or diabetes mellitus.

Administer PPSV23 as soon as possible if the 6- to 12-month time window has passed. Reproduced from Reference 3.

1 year after the most recent vac- Although concerns have been

cination. For those with immune- raised about adverse reactions in

compromising conditions, a sec- patients who receive repeated

ond dose of PPS-23 should be vaccination, in 1 study fewer than

given 5 years after the rst dose. 1% of patients who received at

For those who received either 1 least 3 pneumococcal vaccina-

or 2 doses of PPS-23 before 65 tions had an adverse reaction,

years of age, a repeated dose and no reaction was severe, even

should be given at 65 years of when vaccination was repeated

age or older, provided that 5 in less than 6 years (4). Vaccina-

years have passed since the prior tion reduces the frequency of

dose. Although PCV-13 is gener- bacteremic pneumonia in

ally given before PPS-23, current healthy, immune-competent 3. Kim DK, Bridges CB, Harri-

man KH, et al. Advisory

vaccine recommendations allow adults. Not all randomized, con- Committee on Immuniza-

PPS-23 to be given rst in per- trolled trials (RCTs) have found tion Practices Recom-

mended Immunization

sons younger than 65 years who reductions in the frequency of Schedule for Adults Aged

have chronic health conditions bacteremic pneumonia in adults 19 and Older: United

States, 2015. Ann Intern

but are not immune-suppressed with chronic illness, although Med 2015;162:214-23.

PMID: 25654609]

and have not had splenectomy case control studies report 4. Walker FJ, Singleton RJ,

(3) (Figure). reductions from 56% 81%. Bulkow LR, et al. Reactions

after 3 or more doses of

pneumococcal polysaccha-

Pneumococcal vaccination In a double-blind RCT of 84 496 adults older ride vaccine in adults in

should be considered for anyone Alaska. Clin Infect Dis.

than 65 years, PCV-13 prevented both bactere- 2005;40:1730-5. [PMID:

hospitalized for a medical illness. mic and nonbacteremic, vaccine strainspecic 15909258]

6 October 2015 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC3 2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

pneumococcal pneumonia and vaccine-type which some patients believe

invasive pneumococcal pneumonia; however, themselves to be allergic) that

it did not prevent all-cause CAP (5). are present in the inactivated

In an RCT of 1006 nursing home residents in vaccine or the live attenuated

Japan, PPS-23 signicantly reduced the fre- nasal vaccine. Live attenuated

quency and mortality of pneumococcal pneu- vaccine can be given intranasally

monia, as well as the frequency but not the to healthy, nonpregnant adults

mortality of all-cause pneumonia (6). up to age 49 years. It should not

be given to health care workers

The efcacy of pneumococcal

who are in contact with (and able

vaccine has not been established

to transmit the virus to) severely

in patients with sickle cell dis-

ease, chronic renal failure, immu- immune-compromised patients

5. Bonten MJM, Huijts SM,

noglobulin deciency, Hodgkin or to those with immunosuppres-

Bolkenbaas M, et al. Poly-

saccharide Conjugate disease, lymphoma, leukemia, or sion and chronic medical condi-

Vaccine Against Pneumo-

multiple myeloma. Use of the tions. A high-dose inuenza vac-

coccal Pneumonia in

Adults. N Engl J Med. 7-valent conjugate vaccine in cine (4 times the standard dose)

2015;372:1114-1125. is available for individuals older

[PMID:25785969] children led to herd immunity for

6. Maruyama T, Taguchi O,

older adults who live with immu- than 65 years. In 1 randomized

Niederman MS, et al.

Efcacy of 23-valent pneu- nized children, but necrotizing trial, this vaccine led to a higher

mococcal vaccine in pre-

pneumonia caused by nonvac- antibody response and better

venting pneumonia and

improving survival in cine strains may be more com- protection against laboratory-

nursing home residents:

double blind, randomised mon in children who receive this conrmed inuenza in persons

and placebo controlled

vaccine (7). older than 65 years than in those

trial. BMJ. 2010;340:

c1004. [PMID: 20211953] who received the standard inu-

7. Bender JM, Ampofo K, What is the role of inuenza enza vaccine (8).

Korgenski K, et al. Pneu-

mococcal necrotizing vaccination in the prevention

pneumonia in Utah: does of CAP and its complications? In a meta-analysis of 20 studies, inuenza vac-

serotype matter? Clin

Infect Dis. 2008;46:1346- All patients at increased risk for cine was shown to reduce pneumonia by 53%,

52. [PMID: 18419434]

inuenza complications and such hospitalization by 50%, and mortality by 68%

8. DiazGranados CA, Dun-

ning AJ, Kimmel M, et al. persons as health care workers (9). In addition, observational studies suggest

Efcacy of high-dose ver- that inuenza vaccine can reduce all-cause

sus standard-dose inu- who are more likely to transmit

enza vaccine in older mortality during inuenza season by 27%

the infection to high-risk patients

adults. N Engl J Med. 54% as well as being cost-effective due to its

2014;371:635-648. (immune-suppressed, elderly, ability to reduce hospitalization rates for con-

[PMID: 25119609]

9. Gross PA, Hermogenes and those with chronic medical gestive heart failure and pneumonia in elderly

AW, Sacks HS, et al. The illness), should be immunized persons (10). However, recent analyses ques-

efcacy of inuenza vac-

cine in elderly persons. A yearly. Adults aged 18 49 years tion these benets, noting that few RCTs have

meta-analysis and review

of the literature. Ann In-

can receive recombinant inu- been conducted in these populations and that

tern Med. 1995;123:518- enza vaccine, which does not selection bias may lead to vaccination of

27. [PMID: 7661497]

10. Nichol KL, Margolis KL, contain the egg proteins (to healthier persons (11, 12).

Wuorenma J, et al. The

efcacy and cost effec-

tiveness of vaccination

against inuenza among Prevention... Persons at risk for CAP and its complications should be

elderly persons living in offered pneumococcal and inuenza vaccination at the doses and fre-

the community. N Engl J

Med. 1994;331:778-84. quencies described here. In nonvaccinated individuals in whom pneu-

[PMID: 8065407] mococcal vaccine is indicated, give PCV-13 rst followed by PPS-23

11. Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services. Hos-

6 12 months later in immune-competent persons but after only 8 weeks

pital Quality Initiative in immune-suppressed patients. For persons who have previously re-

Overview. Accessed at ceived PPS-23, give 1 dose of PCV-13 at least 1 year after the prior im-

www.cms.hhs.gov

/HospitalQualityInits munization. Repeat PPS-23 vaccination after 5 years in persons older

/Downloads/Hospital- than 65 years who received the previous (1 or 2) doses before age 65

overview.pdf on 24 Au-

gust 2009.

years, and after 5 years at any age in immune-suppressed patients. In-

12. Nelson JC, Jackson ML, uenza vaccine should be offered yearly to at-risk persons, including

Weiss NS, Jackson LA. health care workers, with consideration of the high-dose vaccine in per-

New strategies are

needed to improve the sons older than 65 years. Patients hospitalized with a medical illness

accuracy of inuenza should be considered for both of these vaccines.

vaccine effectiveness

estimates among se-

niors. J Clin Epidemiol.

2009;62:687-94. [PMID:

19124221]

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

2015 American College of Physicians ITC4 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 October 2015

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

Diagnosis

Which symptoms should lead present for longer periods in el-

clinicians to consider CAP? derly persons.

Pneumonia usually presents with Which organisms cause CAP?

both respiratory and systemic

The most commonly identied

symptoms, particularly in young

bacterial pathogens for CAP are

patients and immune-competent

Streptococcus pneumoniae

persons. It should be suspected

(pneumococcus); Haemophilus

when the patient has cough, pu-

rulent sputum, pleuritic chest inuenzae; and atypical patho-

pain, dyspnea, chills, fever, night gens, such as Mycoplasma pneu-

sweats, and weight loss. Fever moniae, Chlamydophila pneu-

and chills have a sensitivity of moniae, and Legionella. Patients

50% 85% but may be absent in older than 65 years and those

elderly persons. Dyspnea has a with alcoholism, noninvasive dis-

sensitivity of 70% for the diagno- ease, antibiotic therapy within 3

sis of CAP, whereas purulent spu- months, multiple medical comor-

tum has a sensitivity of only 50%. bid conditions, exposure to chil-

Hemoptysis suggests necrotizing dren in a day care center, or im-

infection, such as lung abscess, munosuppressive illness are

tuberculosis, or gram-negative more likely to have drug-resistant

pneumonia. Many older patients pneumococcus (DRSP) than

and those with chronic illness other patients (Table).

have a weaker immune response,

and the disease may go unrecog- A cohort study of 3339 patients with invasive

pneumococcal infection found that if the pa-

nized because the patient has

tient had received penicillin, macrolide, uoro-

only nonrespiratory symptoms.

quinolone, or trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole

These symptoms include confu- therapy 3 months before the onset of bactere-

sion, weakness, lethargy, falling, mia, the organism was more likely to be resis-

poor oral intake, and decompen- tant to the antibiotic recently received (13).

sation of a chronic illness (for ex-

ample, congestive heart failure). Viruses can also cause CAP, and

Most patients with CAP present 1 recent study found viruses in

with an acute illness 12 days in 18% of all patients who had

duration, but symptoms may be paired serologies. The most com-

Table. Modifying Factors That Increase the Risk for Infection With Specic

Pathogens

Organism Risk Factor

Penicillin-resistant and Age >65 years

drug-resistant pneumococci -lactam therapy within the past 3 months

Alcoholism

Immune-suppressive illness (including therapy with

corticosteroids)

Multiple medical comorbid conditions

Exposure to a child in a day care center

Enteric gram-negative bacteria Residence in a nursing home

Underlying cardiopulmonary disease

Multiple medical comorbid conditions

Recent antibiotic therapy

Pseudomonas aeruginosa Structural lung disease (bronchiectasis) 13. Toronto Invasive Bacterial

Corticosteroid therapy (prednisone, >10 mg/d) Disease Network. Predict-

Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy for >7 d in the ing antimicrobial resis-

past month tance in invasive pneu-

Malnutrition mococcal infections. Clin

Infect Dis. 2005;40:

1288-97. [PMID:

15825031]

6 October 2015 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC5 2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

mon viral organisms were inu- those with poor functional status,

enza and parainuenza virus, fol- severe illness, recent antibiotic

lowed by respiratory syncytial therapy, and recent hospitaliza-

virus and adenovirus. Viruses are tion (18). Methicillin-resistant S.

also common in patients with se- aureus (MRSA) can occur in pa-

vere CAP, especially with the ad- tients with HCAP and in previ-

vent of molecular diagnostic ously healthy persons after inu-

methods. In a study of 198 ICU enza, particularly in the form of a

patients with CAP or HCAP, vi- severe, bilateral, necrotizing in-

ruses were present in 72, using fection (19, 20).

real-time polymerase chain reac-

14. Choi SH, Hong SB, Ko What is the role of history and

GB, et al. Viral infection tion (PCR) testing or shell vial cul-

in patients with severe physical examination in the

pneumonia requiring tures of either bronchoalveolar

intensive care unit ad- lavage or nasal swabs. Rhinovi-

diagnosis of CAP?

mission. Am J Respir Crit

rus, parainuenza, inuenza, and History and physical examination

Care Med. 2012;186:

325-32. [PMID: respiratory syncytial virus were are valuable for suggesting the

22700859]

15. Wiemken T, Peyrani P, most common (14). In another presence of pneumonia, predict-

Bryant K, et al. Incidence

study of 468 ICU patients, viruses ing the cause, and helping to de-

of respiratory viruses in

patients with were present in 23% of adults, ne severity. The history can

community-acquired

using PCR testing of nasopharyn- identify risk factors for HCAP,

pneumonia admitted to

the intensive care unit:

geal swabs (15). Gram-negative such as hospitalization or antibi-

results from the Severe

Inuenza Pneumonia bacteria have been found in up otic therapy in the past 90 days,

Surveillance (SIPS) proj- residence in a long-term care

ect. Eur J Clin Microbiol to 10% of patients with CAP (al-

facility, long-term dialysis, outpa-

Infect Dis. 2013;32:705- though some of these patients

10. [PMID: 23274861] tient wound care, or home infu-

16. Arancibia F, Bauer TT, are now classied as having

Ewig S, et al. sion therapy. It can also identify

Community-acquired HCAP), particularly those with a

patients who might have a less

pneumonia due to gram- history of chronic cardiopulmo-

negative bacteria and common cause of pneumonia,

pseudomonas aerugi- nary disease, residence in a nurs-

nosa: incidence, risk, and such as bird (Chlamydia psittaci,

ing home, multiple medical co-

prognosis. Arch Intern Cryptococcus neoformans) or bat

Med. 2002;162:1849- morbid conditions, recent

58. [PMID: 12196083] (Histoplasma capsulatum) expo-

17. El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, antibiotic therapy, renal insuf-

sure or travel to the southwestern

Bhat A, et al. Microbiol- ciency, chronic liver disease, dia-

ogy of severe aspiration United States (endemic fungi,

pneumonia in institu- betes, or active cancer (16). Pseu-

tionalized elderly. Am J such as coccidioidomycosis). In

domonas aeruginosa should be

Respir Crit Care Med. addition to fever, dyspnea,

2003;167:1650-4. considered in persons with bron-

[PMID: 12689848] cough, and pleuritic chest pain,

18. Maruyama T, Fujisawa T, chiectasis, recent hospitalization,

symptoms can include confusion,

Okuno M, et al. A new or recent antibiotic therapy. Al-

strategy for health care- weakness, falling, lethargy, re-

associated pneumonia: a though anaerobic organisms

2-year prospective multi- duced oral intake, or deteriora-

should be considered when aspi-

center cohort study using tion due to a chronic illness (such

risk factors for multidrug- ration is a possibility (for exam-

resistant pathogens to as congestive heart failure).

select initial empiric ple, in elderly patients with neu-

therapy. Clin Infect Dis. rologic or swallowing disorders),

2013;57:373-83. [PMID: Clinical examination ndings

23999080] in 1 study the most common or- suggestive of pneumonia include

19. Carratala J, Mykietiuk A,

Fernandez-Sabe N, et al. ganisms identied in persons at fever or hypothermia, tachypnea,

Health care-associated risk for aspiration were gram- crackles, bronchial breath sounds

pneumonia requiring

hospital admission: negative bacteria (17). Klebsiella on auscultation, and pleural effu-

epidemiology, antibiotic

therapy, and clinical

pneumoniae has been reported sion. Specic ndings that are

outcomes. Arch Intern in patients with alcoholism. Al- associated with a poor outcome

Med. 2007;167:1393-9.

[PMID: 17620533] though some studies suggest include a respiratory rate greater

20. Infectious Diseases Soci- that HCAP pathogens are more than 30 breaths/min, diastolic

ety of America. Infectious

Diseases Society of Amer- similar to those in hospital- blood pressure less than 60 mm

ica/American Thoracic

Society consensus guide-

acquired pneumonia than to Hg, systolic blood pressure less

lines on the manage- those in CAP, not all studies con- than 90 mm Hg, heart rate

ment of community-

acquired pneumonia in rm these ndings. Patients with greater than 125 beats/min, and

adults. Clin Infect Dis. HCAP who are most at risk for temperature less than 35 C or

2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-

72. [PMID: 17278083] drug-resistant organisms are greater than 40 C. An elderly

2015 American College of Physicians ITC6 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 October 2015

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

person with CAP may present present even in the absence of a

with nonrespiratory symptoms radiographic inltrate if the pa-

and ndings because of an im- tient has a convincing history

paired immune and inammatory and focal physical ndings; a fol-

response. low-up radiograph may show an

inltrate. Interobserver variability

When should clinicians use

in chest radiographic interpreta-

chest radiography?

tion was shown in 1 study that

A chest radiograph should be

compared the readings of

obtained in all patients with clini-

at least 2 radiologists. Positive

cal features suggesting CAP to

agreement (59%) was less fre-

dene the presence of parenchy-

quent than negative agreement

mal lung infection and to identify

(94%) (23).

certain pneumonia complica-

tions. Clinical diagnosis of pneu- What is the role of other

monia is often inaccurate and has laboratory tests?

an overall sensitivity ranging For outpatients, perform pulse

from 70%90% and a specicity oximetry to assess oxygenation.

ranging from 40%70% (20, 21). No other tests are needed. For

Elderly and immunosuppressed inpatients, additional testing is

patients can have radiographic done to dene disease severity

evidence of pneumonia without and identify the cause. Measure

clear-cut clinical features. In 1 pulse oximetry in all patients and

study, measurement of serum arterial blood gases in those sus-

procalcitonin levels added to pected of having carbon dioxide

physical examination data in- retention. Even with extensive di-

creased the predictive value of agnostic testing, a specic cause is

an abnormal chest radiograph (22). found in fewer than half of all pa-

When history (cough, fever, dyspnea, pleuritic tients. Sputum should be collected

pain) and physical examination ndings (focal for Gram stain and culture before

crackles, temperature 38 C) were used to therapy is started in patients sus-

predict the presence of radiographic pneumo- pected of being infected with a

nia in a study of 129 patients with lower respi- drug-resistant or unusual patho-

ratory tract infection (26 with pneumonia), no gen, but evaluation of sputum

combination of ndings was highly accurate. should be done only if it is of good

The positive predictive value of each nding quality and processed rapidly.

varied from 17% 43% (21).

Rapid diagnostic testing of respira-

It is especially important to have tory secretions with molecular

a chest radiograph if the diagno- methods (such as PCR) is now be- 21. Graffelman AW, le Cessie

sis is questionable or if pleural coming widely available, although S, Knuistingh Neven A,

et al. Can history and

effusion, lung abscess, necrotiz- their value for patient manage- exam alone reliably

ing pneumonia, or multilobar ment is uncertain because they predict pneumonia?

J Fam Pract. 2007;56:

illness is suspected. Radiographs may be too sensitive and unable to 465-70. [PMID:

17543257]

can specically aid patient man- distinguish colonization from infec- 22. Muller B, Harbarth S,

agement if ndings of severe ill- tion. In patients with severe pneu- Stolz D, et al. Diagnostic

and prognostic accuracy

ness are present (bilateral, multi- monia, 2 sets of blood cultures of clinical and laboratory

should be collected and urine parameters in

lobar, or rapidly expanding community-acquired

inltrates), but patterns only tested for Legionella and pneumo- pneumonia. BMC Infect

Dis. 2007;7:10. [PMID:

rarely suggest a specic diagno- coccal antigens. Limit blood cul- 17335562]

sis or cause (e.g., tuberculosis, P. tures to patients with severe ill- 23. Hopstaken RM, Witbraad

T, van Engelshoven JM,

jiroveci). If pleural effusion is ness; these cultures are positive in Dinant GJ. Inter-observer

variation in the interpre-

present, conrmation should be only 10%20% of all patients with tation of chest radio-

obtained with a decubitus lm, CAP. In low-risk patients (without graphs for pneumonia in

community-acquired

thoracic ultrasonography, or severe illness), the incidence of lower respiratory tract

computed tomography. Pneumo- false-positive results may exceed infections. Clin Radiol.

2004;59:743-52. [PMID:

nia should be assumed to be the incidence of true-positive re- 15262550]

6 October 2015 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC7 2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

sults (20, 24). Culture an endotra- role in the routine management

cheal aspirate in patients who are of CAP is not dened. Serum

intubated and mechanically levels of procalcitonin identify

ventilated. patients who can benet from

antibiotic therapy; levels are ele-

A study of 13 043 Medicare patients identied the

vated with bacterial and Legion-

following predictors of true-positive results on blood

ella infection, but not always with

culture: no previous receipt of antibiotics, underlying

liver disease, systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, other atypical pathogen infec-

temperature <35 C or >40 C, pulse >125/min, tion, and not with viral infection.

blood urea nitrogen levels >10.71 mmol/L (30 mg/ Serial measurements of procalci-

dL), serum sodium levels <130 mmol, and leuko- tonin levels may help guide when

cyte count <5 or >20 109 cells/L. The diagnostic to stop antibiotic therapy (26).

yield of blood cultures increased in patients with 1 or

more of the above predictors and in those who had A randomized trial of 302 patients with CAP

not received antibiotics before blood collection (24). compared patients managed by usual care

with those managed by an algorithm recom-

Do not perform serologic tests mending antibiotics and the duration of ther-

for viruses and atypical patho- apy. The algorithm was based on serial mea-

gens because they require con- surement of procalcitonin levels using the

valescent titers 6 8 weeks after highly sensitive Kryptor assay. Procalcitonin

the initial test to identify infec- levels were measured on admission and after

tion. Rapid diagnostic tests that 6 24 hours, 4 days, 6 days, and 8 days. The

can evaluate for viral pathogens procalcitonin-guided group had signicantly

fewer antibiotic prescriptions on admission

on nasopharyngeal swabs, such

and less antibiotic use, and the duration of

as rapid antigen testing, direct therapy was reduced from 12 to 5 days with

uorescent antibody, or PCR, are similar clinical success (27). Measurement of

available. However, the role of serum procalcitonin, using the Kryptor assay at

these tests in managing patients the time of admission, has been shown in 4

with CAP and in guiding antibi- randomized studies (of both single-center and

24. Metersky ML, Ma A, otic selection are not yet estab- multicenter design) to reduce antibiotic use. In

Bratzler DW, Houck PM.

Predicting bacteremia in lished, although some studies these studies, antibiotic therapy was discour-

patients with have shown that they may reduce aged when the procalcitonin level was <0.25

community-acquired

pneumonia. Am J Respir unnecessary antibiotic use and g/L, with no adverse effects on mortality (26).

Crit Care Med. 2004;

169:342-7. [PMID:

increase antiviral use, especially What other disorders should

14630621] when results are positive for inu- clinicians consider in patients

25. van der Eerden MM,

Vlaspolder F, de Graaff enza. Regardless, establishing a

suspected of having CAP?

CS, et al. Comparison specic cause is usually not nec-

between pathogen di- If the patient does not respond to

rected antibiotic treat- essary because empirical therapy

ment and empirical empirical therapy after 48 72

broad spectrum antibi-

is effective. For example, when

hours, consider the possibility of

otic treatment in patients pathogen-directed treatment

with community ac- a virus or an unusual bacterial

quired pneumonia: a was compared with empirical

prospective randomised pathogens, such as Mycobacte-

treatment using a broad-spec-

study. Thorax. 2005;60: rium tuberculosis (which may be

672-8. [PMID: trum antibiotic, the 2 groups did

16061709] masked by a partial response to

26. Upadhyay S, Niederman not signicantly differ in the

empirical quinolone therapy of

MS. Biomarkers: what is length of hospital stay, 30-day

their benet in the iden- CAP) or endemic fungi (histoplas-

tication of infection, mortality, clinical failure, or reso-

severity assessment, and mosis, coccidioidomycosis, blas-

management of

lution of fever (25).

community-acquired

tomycosis). Also consider non-

pneumonia? Infect Dis Measurement of serum levels of infectious possibilities, such as

Clin North Am. 2013

27:19-31. [PMID: C-reactive protein or procalci- bronchiolitis obliterans with or-

3398863] tonin may be helpful to dene ganizing pneumonia, pulmonary

27. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D,

Bingisser R, et al. Procal- which patients have bacterial vasculitis, hypersensitivity pneu-

citonin guidance of anti-

biotic therapy in

pneumonia, to decide whether to monitis, interstitial diseases, lung

community-acquired start antibiotic therapy, to deter- cancer, lymphangitic carcinoma,

pneumonia: a random-

ized trial. Am J Respir mine prognosis, and to provide bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma,

Crit Care Med. 2006; supportive information in the lymphoma, and congestive heart

174:84-93. [PMID:

16603606] site-of-care decision, but their failure. If the patient's condition de-

2015 American College of Physicians ITC8 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 October 2015

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

teriorates after an initial response to patients do not respond to initial tomycosis), Pasteurella multo-

therapy, consider pulmonary em- empirical therapy. An infectious cida, Bacillus anthracis,

bolus; antibiotic-induced colitis; and disease specialist can help iden- Actinomyces Israeli, Francisella

the pneumonia complications of tify infectious complications of tularensis (tularemia), Yersinia

empyema, meningitis, and pneumonia and unusual infec- pestis (plague), or Chlamydia

endocarditis. tions, such as Coxiella burnetii (Q psittaci (psittacosis). A pulmo-

fever), Burkholderia pseudomallei nary specialist can help identify

When should clinicians (melioidosis), Mycobacterium inammatory lung disease and

consider specialty consultation tuberculosis (which may be pulmonary embolus and per-

for diagnosis, and which types masked by a partial response to form bronchoscopy and trans-

of specialists should they consult? empirical quinolone therapy of bronchial biopsy. A surgeon can

Consultation is most valuable to CAP) , endemic fungi (histoplas- perform thoracoscopic or open

clarify diagnostic questions when mosis, coccidioidomycosis, blas- lung biopsy.

Diagnosis... History is particularly valuable for dening risk factors for

specic pathogens, and physical ndings help dene disease severity.

Clinical ndings are less dramatic in elderly persons. Conrm the diag-

nosis of CAP with a chest radiograph, although this test is not always

denitive early in the course of illness. Laboratory testing has limited

value; however, it can be used in conjunction with other data to dene

severity and to identify systemic and respiratory complications. Diag-

nosing specic pathogens early is less useful because most initial ther-

apy is empirical. If the patient does not respond to initial therapy, con-

sult specialists and consider bronchoscopy and lung biopsy for a

denitive diagnosis.

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

Treatment

How should clinicians the hospital. The BTS rule has patients who had low levels of procalcitonin had

determine whether a patient been condensed into the CURB- low mortality, regardless of PSI class or number

with CAP requires outpatient, 65, which is based on the pres- of CURB-65 points (29).

inpatient, or ICU care? ence of Confusion, blood Urea Current guidelines support ICU

Many site-of-care decisions can nitrogen >7.0 mmol/L (19.6 mg/ care if the patient needs assisted

be facilitated with the pneumonia dL), Respiratory rate 30 ventilation, has septic shock re-

severity index (PSI) or the British breaths/min, systolic Blood pres- quiring vasopressors, or has at

Thoracic Society (BTS) rule. sure <90 mm Hg or diastolic least 3 of the following: respira-

These tools predict risk for death. blood pressure <60 mm Hg, and tory rate 30 breaths/min, PaO2/

Patients at high risk are generally age 65 years. Patients with at FiO2 ratio 250, multilobar inl-

managed in the hospital, and least 2 of these criteria are usu- trates, confusion or

those at highest risk are man- ally admitted to the hospital, disorientation, blood urea nitro-

aged in the ICU. The PSI straties whereas those with at least 3 gen 7.1 mmol/L (20 mg/dL),

patients into 5 categories by us- criteria are considered for ICU leukocyte count <4 109 cells/L,

ing a scoring system based on admission (20, 28, 29). platelet count <100 109

patient age, comorbid illness, cells/L, temperature lower than

physical examination ndings, One prospective study of 3181 patients seen

36 C, and hypotension requir-

and laboratory data. In general, in 32 emergency departments compared the

ing aggressive uid resuscitation

PSI with the CURB and CURB-65 criteria and

patients in classes I and II are (20). One study found that leu-

found that both approaches accurately identi-

treated as outpatients, those in ed low-risk patients. CURB-65 was better for kopenia, thrombocytopenia, and

class III have the site-of-care deci- predicting mortality in high-risk patients (28). In hypothermia were each present

sion based on careful clinical as- another prospective study of 1651 patients, mea- in <5% of all patients; further,

sessment, and those in classes IV surement of serum procalcitonin levels supple- omitting these criteria and re-

and V are generally admitted to mented data obtained by prognostic scoring, and placing them with acidosis sim-

6 October 2015 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC9 2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

plied the prediction of need for doxime, or cefuroxime) with a

ICU admission without a loss of macrolide or doxycycline. If the

accuracy (30). patient has received an antibiotic

in the past 3 months, avoid using

What is the role of nondrug

an antibiotic of the same class.

therapies?

In outpatients, nondrug therapy How long should outpatients

should focus on encouraging continue antibiotic treatment?

oral hydration. For hospitalized The duration of therapy should

patients, nondrug therapies in- be based on the patient's clinical

clude intravenous hydration and response, severity of illness, and

oxygen for hypoxemia. Chest probable pathogen. Outpatients

physiotherapy has not been with mild-to-moderate CAP can

widely studied, but it has been be treated for as few as 5 days if

shown to improve the outcome clinical response is good, there

of patients with pneumonia who has been no fever for 48 to 72

have more than 30 mL/d of spu- hours, and there are no signs of

tum and impaired clearance of extrapulmonary infection. Azi-

secretions (31). A meta-analysis thromycin has such a long half-

of 6 randomized trials in 434 pa- life that therapy for 1 or 3 days

tients evaluated the following 4 may be effective.

types of chest physiotherapy:

conventional chest physiotherapy, A meta-analysis of 15 RCT studying mild-to-

active cycle breathing, osteopathic moderate CAP found that therapy for 7 days or

fewer was as effective as longer therapy with

manipulation, and positive expira-

regard to clinical failure, mortality, adverse

tory pressure. No method reduced events, and bacteriologic eradication. The trials

28. Aujesky D, Auble TE,

mortality, whereas osteopathic compared only monotherapies, and 13 of the

Yealy DM, et al. Prospec- manipulation and positive expira- short-duration trials used azithromycin, uoro-

tive comparison of three

validated prediction rules tory pressure reduced the duration quinolones, or ketolides, which provide cover-

for prognosis in of hospital stay by 2.02 and 1.4 age for both pneumococcus and atypical

community-acquired

pneumonia. Am J Med. days, respectively (32). In the se- pathogens. Only 2 short-duration trials used

2005;118:384-92. verely ill ICU patient, nondrug -lactam monotherapy (33).

[PMID: 15808136]

29. Huang DT, Weissfeld LA, therapy can include noninvasive How should clinicians follow

Kellum JA, et al. Risk

ventilatory support and mechani-

prediction with procalci- patients during outpatient

tonin and clinical rules in cal ventilation for those with respi-

community-acquired treatment?

pneumonia. Ann Emerg ratory failure.

Med. 2008;52:48-58. Up to 10% of patients initially

[PMID: 18342993] Which antibiotics should be managed at home do not re-

30. Salih W, Schembri S,

Chalmers JD. Simplica- prescribed for outpatients? spond to outpatient therapy and

tion of the IDSA/ATS

criteria for severe CAP For patients with no cardiopul- require hospitalization. To iden-

using meta-analysis and monary disease and no factors tify these patients early, the phy-

observational data. Eur

Respir J 2014;43:842- that increase risk for infection sician and patient should agree

851. [PMID: 24114960]

31. Graham WG, Bradley DA.

with DRSP or enteric gram- on a plan to monitor the re-

Efcacy of chest physio- negative bacteria (Table), pre- sponse to therapy. Ask patients

therapy and intermittent

positive-pressure breath- scribe a macrolide (azithromycin, to measure their temperature

ing in the resolution of clarithromycin, or erythromycin) orally every 8 hours and to report

pneumonia. N Engl J

Med. 1978;299:624-7. or doxycycline (Appendix Table, if it exceeds 38.3 C (101 F) or

[PMID: 355879]

32. Yang M, Yan Y, Yin X,

available at www.annals.org). For does not decrease below 37.2 C

et al. Chest physiother- outpatients who have cardiopul- (99 F) after 48 hours. Encourage

apy for pneumonia in

adults. Cochrane Data- monary disease or factors that patients to drink at least 1 to 2

base Syst Rev. 2013 Feb

28;2:CD006338.

increase the risk for infection with quarts of liquid daily and to report

33. Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DRSP or enteric gram-negative if they cannot achieve this goal.

DH, Bent S. Efcacy of

short-course antibiotic bacteria, prescribe an antipneu- Instruct patients to report symp-

regimens for mococcal quinolone (levooxacin toms of chest pain, severe or in-

community-acquired

pneumonia: a meta- or moxioxacin) or a combination creasing shortness of breath, or

analysis. Am J Med.

2007;120:783-90.

of a -lactam (amoxicillin, 3 g/d; lethargy. Encourage patients to

[PMID: 17765048] amoxicillin clavulanate, cefpo- take their antibiotics on schedule

2015 American College of Physicians ITC10 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 October 2015

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

and to continue taking them even DRSP or gram-negative bacteria

after they begin feeling better and (20, 36), very few such patients

until they have taken all of them. are hospitalized, and this is not a

commonly used approach. Most 34. Meehan TP, Fine MJ,

If the response to therapy is satis- hospitalized patients not in the Krumholz HM, et al.

Quality of care, process,

factory, ask the patient to return ICU have cardiopulmonary dis- and outcomes in elderly

for an examination in 10 14 days. ease or factors that increase the

patients with pneumo-

nia. JAMA. 1997;278:

Give pneumococcal and inu- risk for DRSP or gram-negative 2080-4. [PMID:

9403422]

enza vaccinations at the outpa- bacteria, and they should receive 35. Kanwar M, Brar N,

tient visit if they have not previ- an intravenous or oral quinolone

Khatib R, Fakih MG.

Misdiagnosis of

ously been given. Obtain a (levooxacin, 750 mg/d, when community-acquired

repeated chest radiograph no renal function is normal, or moxi-

pneumonia and inappro-

priate utilization of anti-

sooner than 1 month after start- oxacin, 400 mg/d) or the combi- biotics: side effects of the

4-h antibiotic administra-

ing pneumonia therapy to screen nation of a -lactam (cefotaxime, tion rule. Chest. 2007;

for nonresolution of inltrates, ceftriaxone, ampicillinsulbac-

131:1865-9. [PMID:

17400668]

which could be due to lung can- tam, or high-dose ampicillin, but 36. Feldman RB, RhewDC,

cer, inammatory disease, or an Wong JY, et al. Azithro-

not cefuroxime) with a macrolide mycin monotherapy for

unusual infection (20). Assess the or doxycycline (20). The addition patients hospitalized

with community-

patient's overall health and look of a macrolide to a -lactam has acquired pneumonia: a

for decompensated comorbid been associated with reduced

31/2-year experience

from a veterans affairs

illness to attempt to prevent fu- mortality and hospital stay (37), hospital. Arch Intern

ture episodes of pneumonia. Med. 2003;163:1718-

even for bacteremic pneumococ- 26. [PMID: 12885688]

37. Martnez JA, Horcajada

When patients require cal pneumonia (37). In contrast, JP, Almela M, et al. Addi-

hospitalization, how soon after in a randomized trial of 580 tion of a macrolide to a

beta-lactam-based empir-

admission should antibiotics be immune-competent patients, ical antibiotic regimen is

started, and which antibiotics -lactam monotherapy was not associated with lower

in-hospital mortality for

inferior to a -lactammacrolide patients with bacteremic

should patients receive if they pneumococcal pneumo-

combination in patients with nia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;

do not need ICU care?

moderately severe CAP. How- 36:389-95. [PMID:

Patients should receive initial an- ever, patients with atypical

12567294]

38. Garin N, Genne D, Car-

tibiotic therapy as soon as possi- pathogens and those in PSI class ballo S, et al. -Lactam

ble after the diagnosis is estab- monotherapy vs

IV had delayed clinical stability -lactam-macrolide

lished and before they leave the with -lactam monotherapy when

combination treatment

in moderately severe

emergency department. Al-

compared with those receiving community-acquired

though therapy within 4 hours of pneumonia: a random-

combination therapy (38). In an- ized noninferiority trial.

arrival to the hospital has been JAMA Intern Med 2014;

other trial of admitted patients 174:1894-1901. [PMID:

associated with reduced mortal-

with nonsevere CAP, -lactam 25286173]

ity in some studies, undue em- 39. Postma DF, van Werk-

monotherapy was equivalent to a hoven CH, van Elden LJ,

phasis on early therapy can lead

-lactammacrolide combination et al; CAP-START Study

to unnecessary use of antibiotics Group. Antibiotic treat-

for 30 day mortality (which was ment strategies for

and associated complications

<10%) (39). Specic -lactams, community-acquired

pneumonia in adults.

(11, 34). In 1 study, the nal diag-

such as ceftriaxone and cefo- N Engl J Med 2015;372:

nosis of pneumonia in patients 13121323.[PMID:

taxime, are preferred if DRSP is 25830421]

suspected of having pneumonia 40. Lujan M, Gallego M,

suspected because they are ef-

in the emergency department Fontanals D, Mariscal D,

fective at mean inhibitory con- Rello J. Prospective ob-

decreased from 75.9% to 58.9% servational study of bac-

centrations up to 2 mg/L (40). teremic pneumococcal

after the initiation of a program

However, 1 study showed in- pneumonia: Effect of

to give more patients antibiotics discordant therapy on

creased mortality when cefu- mortality. Crit Care Med.

within 4 hours of arrival in the 2004;32:625-31. [PMID:

roxime was used in patients with

emergency department (35). 15090938]

bacteremic DRSP (41). 41. International Pneumo-

coccal Study Group. An

Although guidelines recommend One international study of 4337 hospitalized international prospective

study of pneumococcal

that hospitalized patients who patients with CAP showed that approximately bacteremia: correlation

are not in the ICU receive intrave- 20% had evidence of atypical pathogen infec- with in vitro resistance,

antibiotics administered,

nous azithromycin if they have no tion and that therapy directed against these or- and clinical outcome.

cardiopulmonary disease and no Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:

ganisms decreased the time to clinical stabil- 230-7. [PMID:

factors that increase the risk for ity, length of stay, and both total and CAP- 12856216]

6 October 2015 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC11 2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

related mortality (42). However, another study olone effective against P.

of 2209 hospitalized Medicare patients with aeruginosa (ciprooxacin or high-

bacteremic pneumonia found that therapy di- dose levooxacin). Alternatively,

rected at atypical pathogens reduced 30-day treat patients with risk factors

mortality and 30-day readmission rate, but the with an intravenous, antipseudo-

benets occurred only with macrolides and not

monal -lactam combined with

42. Community-Acquired with uoroquinolones (43).

Pneumonia Organization an aminoglycoside (amikacin,

(CAPO) Investigators. A

worldwide perspective of For patients with HCAP admitted to gentamicin, or tobramycin) plus

atypical pathogens in the hospital but not the ICU, antibi- either an intravenous macrolide

community-acquired

pneumonia. Am J Respir otic choice should be individualized (azithromycin or erythromycin) or

Crit Care Med. 2007;

175:1086-93. [PMID:

based on risk factors for MDR patho- intravenous antipneumococcal

17332485] gens. A CAP regimen is effective for quinolone (levooxacin or moxi-

43. Metersky ML, Ma A,

Houck PM, Bratzler DW. most patients, but therapy directed oxacin). In studies of patients

Antibiotics for bacteremic at multidrug-resistant, gram- admitted to the ICU with severe

pneumonia: improved

outcomes with macro- negative bacteria and MRSA may be CAP, mortality was reduced

lides but not uoro- when combination therapy was

quinolones. Chest. 2007;

needed for patients with nonsevere

131:466-73. [PMID: pneumonia and at least 2 MDR risk used; monotherapy, even with a

17296649]

44. Sligl WI, Asadi L, Eurich factors (recent hospitalization, recent quinolone, was not as effective.

DT, et al. Macrolides and antibiotics, poor functional status,

mortality in critically ill A meta-analysis of 28 observational studies, involv-

patients with immune suppression) or severe

community-acquired ing nearly 10 000 critically ill patients found that

pneumonia: a systematic

pneumonia with at least 1 MDR risk macrolide use (generally in a combination regimen)

review and meta- factor. Therapy for HCAP in patients was associated with an 18% reduction in mortality

analysis. Crit Care Med

2014;42:420-432. at risk for MDR pathogens usually compared with nonmacrolide regimens and that a

[PMID:24158175] requires dual pseudomonal therapy

45. International Pneumo- -lactammacrolide combination had a trend to-

coccal Study Group. plus therapy directed at MRSA. ward reduced mortality compared with a -lactam

Combination antibiotic

therapy lowers mortality quinolone regimen (44). In patients with bacteremic

among severely ill pa- A prospective study of 321 HCAP patients showed pneumococcal pneumonia and critical illness, stud-

tients with pneumococcal that with the use of an algorithm, 93% received ap- ies have found that mortality was lower with combi-

bacteremia. Am J Respir

Crit Care Med. 2004;

propriate therapy, but this was achieved with only nation therapy than with monotherapy (45).

170:440-4. [PMID: 53% requiring broad-spectrum empirical therapy

15184200]

46. Micek ST, Dunne M,

(18). The algorithm stratied patients on the basis of If community-acquired MRSA is sus-

Kollef MH. Pleuropulmo- severity of illness (admission to the ICU or not) and pected, add either linezolid alone or

nary complications of

Panton-Valentine

the presence of other risk factors for MDR pathogens consider vancomycin combined

leukocidin-positive (recent antibiotic therapy, recent hospitalization, with clindamycin, because both of

community-acquired poor functional status, and immune suppression).

methicillin-resistant these regimens are antibacterial and

Staphylococcus aureus: Patients with nonsevere illness and at least 2 MDR

importance of treatment risk factors, or those with severe illness and at least 1

inhibit production of bacterial toxins.

with antimicrobials inhib-

MDR risk factor, were treated empirically with broad- Vancomycin alone is antibacterial

iting exotoxin produc-

tion. Chest. 2005;128: spectrum, multidrug therapy, whereas all others re- but cannot inhibit toxin production

2732-8. [PMID:

16236949] ceived CAP regimens. Through use of this approach, (46). These regimens are recom-

47. Salluh JI, Verdeal JC, mortality was 13.7%. mended, even though the organ-

Mello GW, et al. Cortisol

levels in patients with isms are often sensitive in vitro to

severe community- Which antibiotics should be given

trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole and

acquired pneumonia.

Intensive Care Med.

to patients admitted to the ICU? quinolones.

2006;32:595-8. [PMID: No patient in the ICU should re-

16552616] What are the other components

48. Salluh JI, Povoa P, ceive empirical monotherapy.

Soares M, et al. The role Assess these patients for risk fac- of ICU care for CAP?

of corticosteroids in se-

vere community- tors for P. aeruginosa. Treat those Hydration should be ensured and

acquired pneumonia: a

systematic review. Crit

without risk factors with intrave- supplemental oxygen and chest

Care. 2008;12:R76. nous ceftriaxone or cefotaxime physiotherapy should be consid-

[PMID: 18547407]

49. Torres A, Sibiila O, Ferrer plus either azithromycin or a ered. However, the main determina-

M, et al. Effect of cortico- quinolone, such as levooxacin tion is whether ventilatory support

steroids on treatment

failure among hospital- or moxioxacin. Treat patients for respiratory failure is needed. In-

ized patients with severe

community-acquired

who have risk factors with an in- tubation and mechanical ventilation

pneumonia and high travenous, antipseudomonal are required in patients who have

inammatory response:

a randomized clinical -lactam (cefepime, piperacillin oxygen saturation less than 90% on

trial.JAMA 2015;313: tazobactam, imipenem, mero- maximal mask oxygen, inability to

677-686. [PMID:

25688779] penem) plus an intravenous quin- clear secretions, inability to protect

2015 American College of Physicians ITC12 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 October 2015

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

the airway, or hypercarbia. If the pa- can be made as early as 2448 nary consultation should be re-

tient has only hypoxemia or hyper- hours after admission and is made quested if pleural effusion is docu-

carbia and is alert and cooperative, by day 3 in up to half of all patients. mented and help is needed with a

it may be possible to use noninva- Changing to oral therapy can be decision regarding thoracentesis.

sive positive pressure ventilation. done safely even if pneumococcal Pulmonary or thoracic surgical con-

This therapy may be associated with bacteremia has been documented, sultation is appropriate for place-

fewer complications than endotra- although these patients may take ment of a chest tube if a compli-

cheal intubationincluding longer to respond. Longer durations cated parapneumonic effusion or

ventilator-associated pneumonia of therapy are usually needed for empyema is found on thoracente-

but if it is used, the clinician must patients infected with P. aeruginosa sis, because early therapy can re-

ensure that the patient can expecto- or S. aureus and for those with ex- duce hospital stay and avoid com-

rate any respiratory secretions. Con- trapulmonary complications, such as plications. A thoracic surgeon can

sider systemic corticosteroids, espe- empyema or meningitis, but should also perform surgical decortication

cially if relative adrenal insufciency be individualized to specic patient for advanced and loculated pleural

is suspected, or if a patient with situations. Select an oral regimen effusion and empyema. Cardiology

pneumococcal pneumonia has as- that covers all organisms isolated in consultation may be needed if

sociated meningitis. Routine use of blood or sputum cultures and re- complications of cardiac ischemia

systemic corticosteroids in severe ects the intravenous therapy. For arise or in cases of congestive heart

CAP is not recommended, but pa- some patients, this means a -lac- failure. In a study of 170 patients

tients with severe illness and high tammacrolide combination or quin- with pneumococcal pneumonia,

levels of systemic inammation may olone monotherapy. Patients who 19.4% had at least 1 major cardiac

benet from adjunctive systemic have responded to a -lactammac- event, including 12 with acute myo-

corticosteroids. Because many pa- rolide combination can be contin- cardial infarction, 8 with new-onset

tients with severe CAP also have ued on macrolide monotherapy atrial brillation or ventricular tachy-

systemic sepsis, consider aggressive unless cultures justify dual therapy. cardia, and 13 with newly diag-

hydration, vasopressors, and mea- nosed or worsening heart failure

surement of serum lactate. To facilitate a switch to oral therapy, hospitals should without other cardiac complica-

consider using a standing order set supplemented

tions. Patients with cardiac events

In 1 study of 40 patients with severe CAP when by prospective case management. In a cohort study,

each patient was managed in 3 successive periods

had a signicantly higher mortality

random serum cortisol levels were measured

in the rst 72 hours, 65% of patients met cri- with conventional therapy, a guideline-based order rate (27.3% vs. 8.8%) (51).

teria for adrenal insufciency and 63% of the set supported by prospective case management that When can inpatients be

19 patients with CAP and septic shock also had provided feedback to clinicians, and a guideline-

discharged from the hospital?

adrenal insufciency (47). In 4 studies, includ- based order set alone. Time to clinical stability was

ing randomized trials, evidence was inconsis- similar in all 3 periods, but prospective case man- Patients can be discharged once a

tent for a benet from routine corticosteroid agement led to the greatest reductions in the time to switch to oral therapy is made and

therapy; however, if the patient required corti- oral antibiotics, time from oral therapy to discharge, coexisting medical conditions are

costeroids for another reason (such as underly- and overall length of stay (50). under control. No benet for con-

ing COPD), they seemed to cause no harm tinued hospital observation has

(48). A multicenter RCT of severe CAP com- When should a consultation be

been proven. In 1 study, two thirds

pared 61 patients given 0.5 mg/kg methyl- requested for hospital patients, of clinically stable patients were

prednisolone every 12 hours for 5 days with and which types of specialists or observed while receiving oral ther-

59 patients given placebo. All patients had se- subspecialists should be apy before discharge, and no dete-

vere CAP and a C-reactive protein level greater consulted? rioration occurred during this pe-

than 150 mg/L on admission. The group

An infectious disease or pulmonary riod (52). Another study compared

treated with corticosteroids had less treatment

failure, with no difference in mortality (49). consultation is appropriate if there patients who remained in the hos-

are questions about the selection of pital for 1 day after the switch from

When can clinicians switch initial antibiotic therapy or when the intravenous to oral therapy with

hospitalized patients from patient does not respond to initial those discharged on the day of the

intravenous to oral antibiotics? therapy. A pulmonary or critical care switch. The study excluded patients

A switch from intravenous to oral physician should be consulted for with complicated pneumonia,

antibiotics is indicated once the patients with severe illness to decide those who were not eligible to be

symptoms of cough, sputum pro- about using vasopressors, deter- switched to oral therapy, and those

duction, and dyspnea improve; the mine the appropriate site of care, with lengths of stay less than 3 days

patient is afebrile on 2 occasions 8 decide about the need for ventila- or more than 7 days. There were no

hours apart; and he or she is able to tory support, and to aid in managing differences in mortality or 14-day

receive oral medications. This switch the mechanical ventilator. Pulmo- readmission rate (53). Therapy may

6 October 2015 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC13 2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

need to be continued after dis- enza vaccinations; avoid smoking

charge, but the total duration of cigarettes; and receive optimal ther-

therapy is usually 57 days. apy for comorbid illnesses, such as

What are the indications for congestive heart failure and COPD.

In addition, careful evaluation is

follow-up chest radiography?

needed for medical conditions that

Patients hospitalized for pneumonia

could predispose to recurrent infec-

do not need a routine chest radio-

graph before discharge, but those tion. One study found new comor-

who do not reach clinical stability bid conditions in 6% of patients with

and those who deteriorate despite CAP, including diabetes mellitus,

therapy require an aggressive evalu- cancer, COPD, and HIV infection

50. Fishbane S, Niederman

MS, Daly C, et al. The ation, including an early follow-up (55). The patient should be evalu-

impact of standardized

chest radiograph. If the patient has a ated for aspiration risk factors. If

order sets and intensive

clinical case manage- good clinical response to therapy, a pneumonia recurs in the same loca-

ment on outcomes in

community-acquired chest radiograph should not be re- tion, consideration should be given

pneumonia. Arch Intern peated any earlier than 46 weeks to the possibility of bronchiectasis,

Med. 2007;167:1664-9.

[PMID: 17698690] after initial therapy. Radiographic aspirated foreign body, or endo-

51. Musher DM, Rueda AM,

Kaka AS, Mapara SM.

resolution usually lags behind clini- bronchial obstruction. If the patient

The association between cal resolution by about 68 weeks, has recurrent pneumonia or pneu-

pneumococcal pneumo-

nia and acute cardiac but early improvement is usually monia with an unusual pathogen,

events. Clin Infect Dis. substantial. In a prospective study of immune deciency may be present.

2007;45:158-65. [PMID:

17578773] patients aged 70 years or older,

52. Rhew DC, Hackner D,

58% had a clear chest radiograph The 30-day readmission rate for

Henderson L, Ellrodt AG,

Weingarten SR. The after 3 weeks, but it took 12 weeks CAP patients varied from 16.8%

clinical benet of in-

hospital observation in until at least 75% had radiographic 20.1% in a review of 12 studies

low-risk pneumonia resolution of CAP. Predictors of slow (56). Pneumonia itself was the

patients after conversion

from parenteral to oral resolution included a high comor- cause of readmission in only

antimicrobial therapy.

Chest. 1998;113:142-6.

bidity index, bacteremia, multilobar 17.9%29.4% of patients; how-

[PMID: 9440581] involvement, and infection with en- ever, other common causes were

53. Nathan RV, Rhew DC,

Murray C, et al. In- teric gram-negative bacteria (54). exacerbations of congestive

hospital observation after

antibiotic switch in pneu- How can patients prevent heart failure or COPD. Patients

monia: a national evalu-

ation. Am J Med. 2006; recurrent CAP? with HCAP have a higher risk for

119:512.e1-7. [PMID: readmission than patients with

16750965]

Patients with CAP should be up-to-

54. El Solh AA, Aquilina AT, date with pneumococcal and inu- CAP (57).

Gunen H, Ramadan F.

Radiographic resolution

of community-acquired

bacterial pneumonia in

the elderly. J Am Geriatr Treatment... The most important clinical decisions in the treatment of CAP

Soc. 2004;52:224-9.

[PMID: 14728631] include determining the site of care (outpatient, hospital, or ICU), selecting

55. Falguera M, Martn M, antibiotic therapy, delivering supportive care (oxygen, hydration), and deter-

Ruiz-Gonzalez A, Pifarre

R, Garca M. Community- mining the need for ventilatory support. Antibiotic therapy differs for outpa-

acquired pneumonia as tients, inpatients, and those in the ICU. However, all patients should receive

the initial manifestation timely empirical therapy directed at pneumococcus, atypical pathogens, and

of serious underlying

diseases. Am J Med. other organisms when they have risk factors for those organisms. The PSI and

2005;118:378-83. the CURB-65 aid decisions about the site of care. Patients should be managed

[PMID: 15808135]

56. Prescott HC, Sjoding in the ICU if they require ventilatory or vasopressor support or close observa-

MW, Iwashyna TJ. Diag- tion. Consultation should take place in cases of severe disease and when pa-

noses of early and late tients do not respond to initial therapy or have complications. Inpatients can

readmissions after hospi-

talization for pneumonia. be transitioned to oral antibiotics after treatment response occurs and they are

A systematic review. Ann clinically stable, after which the patient can be discharged and managed on an

Am Thor Soc. 2014;11:

1091-100. [PMID: outpatient basis. Routine follow-up chest radiography should be delayed for

25079245] 46 weeks if the patient is responding well to therapy. During follow-up, pa-

57. Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, tients should be monitored for undiagnosed or ineffectively managed comor-

Reichley R, et al. Read-

mission following hospi- bid illness, up-to-date on pneumococcal and inuenza vaccinations, and en-

talization for pneumonia: couraged to avoid cigarette smoking.

the impact of pneumo-

nia type and its implica-

tion for hospitals. Clin

Infect Dis. 2013;57:362-

367. [PMID:23677872]

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

2015 American College of Physicians ITC14 In the Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine 6 October 2015

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

Practice Improvement

What measures of pneumonia January 2015, data collection on

care are regularly collected and these measures was suspended

publicly reported? because compliance was high

In the past, the Center for Medi- and continued monitoring and

public reporting were not be-

care & Medicaid Services (CMS)

lieved to be valuable. The quality

and the Joint Commission have

measures recommended by pro-

endorsed a set of core mea-

fessional organizations are being

sures for CAP, which focused on

reevaluated, as are the guide-

vaccination, smoking cessation, lines for the treatment of CAP.

antibiotic choice, timing of ther- The CMS will continue to monitor

apy, and doing blood cultures on all-cause mortality rates for pa-

critically ill patients before the tients with CAP, and they will

start of antibiotics. The perfor- monitor, and tie future reim-

mance of individual hospitals in bursement rates to, 30-day

achieving these measures had readmission rates for these

been publicly reported. As of 1 patients.

In the Clinic

Tool Kit

Patient Information

www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000145

.htm

NIH MedLine Plus.

www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/clinicians/diagnosis

-medical-mgmt.html

IntheClinic

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases

-conditions/pneumonia.html

Community-Acquired http://umm.edu/health/medical/ency/articles

Pneumonia /pneumonia-adults-community-acquired

Patient resources in English.

http://umm.edu/health/medical/spanishency/articles

/neumonia-en-adultos-extrahospitalaria

Patient resources in Spanish.

Guidelines

https://www.thoracic.org/statements/resources/mtpi

/idsaats-cap.pdf

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/guidelines-and

-quality-standards/community-acquired-pneumonia

-in-adults-guideline/

Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis

and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia.

6 October 2015 Annals of Internal Medicine In the Clinic ITC15 2015 American College of Physicians

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

WHAT YOU SHOULD In the Clinic

Annals of Internal Medicine

KNOW ABOUT

COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED

PNEUMONIA

What Is Pneumonia?

Pneumonia is a serious infection of the lungs.

Community-acquired pneumonia is a type of

pneumonia that you develop outside of a hospi-

tal or nursing home. It is most commonly caused

by bacteria, but viruses can also cause it. Risk

factors for pneumonia include:

Being 65 years or older

Eating a poor diet

Drinking alcohol

Smoking cigarettes

Having inuenza (the u)

Having a weakened immune system, such as

from old age or a serious disease, like HIV or

cancer

Having periods of time where you lost Drink lots of uids to make sure you stay hydrated.

consciousness, such as from anesthesia, Your doctor may prescribe medicines for

drinking too much, drug use, stroke, and cough and to reduce fever. Feeling tired and

seizure coughing may last for up to a month or longer

before going away.

What Are the Warning Signs of Most patients are treated at home, but some

Pneumonia? who are very ill or who have a greater risk for

complications may have to stay in the hospital.

Long-lasting cough, which can sometimes If you have to stay in the hospital, doctors will

bring up mucus monitor your heart and breathing rates,

Feeling cold and shaky oxygen levels, and temperature. You may also

Fever be given uids and medicines through your

Patient Information

Shortness of breath veins (intravenously).

Chest pains

Feeling tired and weak Questions for My Doctor

Am I contagious?

How Is Pneumonia Diagnosed? What can I do to help relieve my symptoms?

Your doctor will ask you questions about your Why do I still feel so tired?

symptoms and give you a physical How can I prevent another episode of

examination. He or she will listen to your lungs pneumonia?

and heart and check your temperature. Should I be treated at home or in the hospital?

Your doctor will usually order a chest X-ray to When can I start my normal activities again?

see how much your lungs are affected. When can I go back to work?

Your doctor may also order tests of the sputum

(mucous brought up with coughing) and urine to Bottom Line

learn what type of bacteria is causing the Pneumonia is a serious infection of the lungs.

pneumonia. A blood test can show if the infection It is most commonly caused by bacteria.

has spread from the lungs to the blood. Symptoms include shortness of breath,

coughing, chest pains, high fever, and feeling

How Is Pneumonia Treated? cold and shaky.

If your pneumonia is caused by bacteria, your Treatment usually includes antibiotic

doctor will prescribe antibiotics. Your medicines, medicines for cough and fever,

symptoms usually start to go away within a few drinking lots of uids, and rest.

days of starting treatment. It is important to Some people may need to stay in the hospital

nish all of your antibiotics, even if you are if the infection is more serious or if pneumonia

feeling better. does not go away.

For More Information

Medline Plus

www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000145.htm

American Lung Association

www.lung.org/lung-disease/pneumonia/symptoms-diagnosisand

.html

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ by a University of York User on 11/21/2016

Appendix Table. Drug Treatment for Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Agent Mechanism of Action Dosage Benets Side Effects Notes

Antibiotics for Bacteriostatic; binds 600 mg PO or IV q12h Penetrates well into the Myelosuppression Drug interactions may lead

community-acquired to 50 S ribosomal lung and is active particularly to serotonin syndrome.

MRSA subunit to inhibit against MRSA thrombocytopenia, Do not use with tricyclic

Linezolid (Zyvox) bacterial protein vomiting, diarrhea, antidepressants,

synthesis seizures, hypoglycemia monoamine oxidase

inhibitors, or selective

serotonin reuptake

inhibitors. Monitor

blood pressure

Clindamycin* (Cleocin) Bacteriostatic; binds 600 mg PO q8h Can inhibit toxin Diarrhea, esophagitis, Can cause Clostridium

to 50 S ribosomal production by MRSA hypersensitivity difcileassociated

subunit to inhibit diarrhea. Caution with

bacterial protein asthma, severe hepatic

synthesis disease