Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Resilience Families With Autistic Child

Загружено:

Alin HirleaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Resilience Families With Autistic Child

Загружено:

Alin HirleaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 2010, 45(3), 347355

Division on Autism and Developmental Disabilities

Resilience in Families with an Autistic Child

Abraham P. Greeff and Kerry-Jan van der Walt

University of Stellenbosch

Abstract: The primary aim of this study was to identify characteristics and resources that families have that

enable them to adapt successfully and be resilient despite the presence of an autistic child in the family. The study

was rooted within the contextual framework of the Resilience Model of Stress, Adjustment and Adaptation of

McCubbin and McCubbin (1996). Parents of 34 families whose children attend a special school for autistic

learners in the Western Cape, South Africa completed self-report questionnaires and answered an open-ended

question. Resilience factors identified in this study include higher socioeconomic status; social support; open and

predictable patterns of communication; a supportive family environment, including commitment and flexibility;

family hardiness; internal and external coping strategies; a positive outlook on life; and family belief systems.

Autism is a severely debilitating developmen- The presence of an autistic child in the

tal disorder with potentially harmful effects on family may have adverse effects on various

the entire family. It is a chronic disability that domains of family life, including the marital

appears in all racial, ethnic, cultural and social relationship, sibling relationships and adjust-

backgrounds around the world and is more ment, family socialisation practices, as well as

common than childhood cancer, cystic fibro- normal family routines. Because of the de-

sis and multiple sclerosis combined (Autism mands associated with caring for an autistic

Society of America, 2003). A study conducted child, parents do not have much personal

in the United States of America found that time (Court Appointed Special Advocate

autism is now ten times more prevalent than it (CASA) Programme, 2003). The result may be

was in the 1980s (Blakeslee, 2003). Potentially, a weakened affectional bond between parents

270, 000 South African children under the age (Cantwell & Baker, 1984), depression, with-

of six are affected by autism (Autism South drawal of one parent from care-giving respon-

Africa, 2005). Furthermore, the number of sibilities, or even divorce.

children affected is rising by 10 to 17% per Rivers and Stoneman (2003) noted that pa-

year (Autism Society of America, 2003). Be- rental conflict and marital stress lead to be-

cause of the severity of the disorder, many haviour problems, poorer adjustment, lower

families struggle to come to terms with their self-esteem and higher rates of depression in

childs diagnosis and to adjust to having a

the siblings of children with autism. Other

child with special needs in their home. The

stressors for siblings include increased care-

motivation for the present study rests on two

taking responsibilities, stigmatisation, the loss

factors, namely the increase in prevalence

of normal sibling interaction (Dyson, Edgar,

rates of the disorder and the potentially ad-

& Crnic, 1989), feelings of guilt and shame,

verse effects the disorder may have on family

and changes in family roles, structure and

functioning. Consequently, the aim of this

activities (Rodrigue, Geffken, & Morgan,

study was to identify characteristics and re-

1993).

sources that families have that enable them to

adapt successfully. Family routines are often dictated by the

autistic child and must often be changed at

the last minute to accommodate the childs

needs. Other factors causing families to isolate

Correspondence concerning this article should

be addressed to Abraham P Greeff, Department of themselves may include difficulty in finding a

Psychology, University of Stellenbosch, Private Bag reliable person to look after the autistic child,

1, Matieland 7602, SOUTH AFRICA. Email apg@ and fatigue or loss of energy due to the con-

sun.ac.za stant burden of care giving (Sanders & Mor-

Resilience in Families / 347

gan, 1997). Despite the challenges faced by ing and utilising resources, as well as problem

the families of autistic children, some families solving, coping and adaptation; (4) support,

are able to cope remarkably well, although including intrafamily and family-community

others have considerable difficulty in dealing support processes that facilitate adaptation;

with these challenges. and (5) patterns of functioning, which in-

volves the elimination, modification and es-

tablishment of patterns of family functioning

Family Resilience Theory

to bring about balance and harmony, as well

In research on families over the last few years, as adaptation (McCubbin et al.).

there has been a shift from a deficit-based Walsh (2003) formulated a process model

model towards a strengths-based model (Haw- of family resilience and highlighted family

ley & DeHaan, 1996), and the concept of re- qualities that may reduce stress and vulnera-

silience has been extended to include family bility during crisis situations. It includes family

resilience (Walsh, 2003). A family resilience belief systems, approaching hardships as a

approach aims at identifying those factors that shared challenge (Walsh, p. 407), maintain-

contribute to healthy family functioning, ing a positive outlook in adapting to stress,

rather than family deficits (Hawley & DeHaan; and preserving a shared confidence through

McCubbin, Thompson, & McCubbin, 1996). an adverse situation. Furthermore, most fam-

Definitions of family resilience encompass a ilies are able to find comfort, strength and

number of common ideas. First, resilience ap- guidance through connections to cultural and

pears to surface in the face of family difficul- religious traditions (Walsh). Social and eco-

ties or hardships (McCubbin et al.; Walsh), nomic resources, including kin and social

and inherent in resilience is the property of networks, friends, community groups and re-

buoyancy. ligious congregations, are important contrib-

In an attempt to illustrate and describe the utors to family resilience, particularly where

complex notion of family resilience, McCub- the stressor is ongoing (Walsh). Communica-

bin and McCubbin (1996) developed The Re- tion processes that entail clarity of contents,

siliency Model of Family Stress, Adjustment open emotional expression, collaborative

and Adaptation. The model distinguishes be- problem-solving and effective conflict man-

tween two interrelated phases, namely adjust- agement are vital for family resilience

ment and adaptation (McCubbin et al., 1996). (Walsh).

The familys level of adjustment depends on Limited research has been documented

numerous essential interacting elements, that contributes specifically to the understand-

namely the stressor and its severity; family vul- ing of the resiliency process in families, or

nerability; established patterns of family func- which identifies resiliency qualities associated

tioning or family typology; resistance resourc- with family adaptation in families faced with a

es; appraisal of the stressor; and family chronic condition. This study, therefore, con-

problem-solving and coping strategies (Mc- tributes to the field of research on resilience

Cubbin et al.). in families with an autistic child, and serves to

Family adaptation includes a series of adap- recognise health and resilient potential in

tation-oriented components and resiliency families where previously there may only have

processes (McCubbin et al., 1996). These in- been decay.

corporate (1) vulnerabilities, which may in-

clude additional life stressors and changes

Method

that undermine or restrict the familys capac-

ity to achieve a satisfactory level of adaptation; The aim of this study was to identify the char-

(2) resources, which consist of the psycholog- acteristics and resources of families that en-

ical, family, and social resources that families able them to be resilient despite having an

utilise in the process of adaptation; (3) ap- autistic child in the family. A cross-sectional

praisal, which comprises the factors that give survey research design was used. Mixed meth-

meaning to the changes in the family and play ods were used to collect data from one parent

a role in establishing new patterns, eliminat- of each participating family. Qualitative data

ing old patterns, affirming old patterns, creat- were obtained by asking an open-ended ques-

348 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-September 2010

tion, while quantitative data were collected three from facility 3. Twenty-four females and

through the use of various measuring instru- four males completed the questionnaires,

ments based on the Resiliency Model of Stress, while the remaining six parents did not indi-

Adjustment and Adaptation (McCubbin et al., cate their gender. Most of the participating

1996). parents were aged between 34 and 43 (n

28), with the mean age of the group being

36.21 (SD 6.36). The mean age of the other

Participants and Procedure

parent (n 25) in the family was 38.92 (SD

Permission to conduct this study was obtained 5.31). Most of the families were two-parent

from the Western Cape Education Depart- families (n 27), while four parents were

ment and the respective governing bodies of unmarried, one was divorced, one was sepa-

the three facilities through which participants rated and one was widowed. The length of the

were recruited. A letter was then sent via two parental relationship in most families (n

of the facilities to the families that qualified 23) was between seven and 13 years, with a

for the study based on the following criteria: mean length (n 34) of 9.53 years (SD

(1) the family structuretwo-parent families 5.00). Thirty-one of the autistic children were

where both parents are present in the childs male and three were female. The mean age of

life, (2) the age of the autistic childnot older the autistic children (N 34) was 6.48 years

than 10 years, and (3) the families should (SD 2.16). Fifteen of the families had one

have known of their childs diagnosis for a other child apart from the autistic child, while

minimum period of 18 months. The question- 12 had no other children, five had two other

naires were sent with a letter explaining in children, and two families did not indicate

detail the procedure to be followed in answer- whether there were other children. Most of

ing the open-ended question and completing the children (n 25) had been diagnosed

the questionnaires. Due to the low response with autism between one and four years pre-

rate to the letters, those families who had not viously. The mean number of years since di-

responded were contacted telephonically in agnosis (n 33) was 3.24 years (SD 1.90).

order to provide additional information and Eighteen of the families were English speak-

to request their participation. This technique ing, 11 were Afrikaans speaking and five spoke

proved more successful, as the majority of another language at home. Four families were

families agreed to participate. of a lower socioeconomic status, eight were of

The third facility was a private organisation middle socioeconomic status and 21 were of a

that caters primarily for the needs of children higher socioeconomic status. One parent did

with developmental disabilities. In order to not indicate socioeconomic status.

recruit families for the study, the researcher

met with a group of parents at an informal

Measures

gathering held at the organisations offices.

After obtaining informed consent, ten ques- Seven self-report questionnaires were used to

tionnaires were handed out to those who were measure various potential resilience variables.

willing to participate and they were asked to All questionnaires were available in both En-

return them to the facility offices at a later glish and Afrikaans. A biographical question-

date. naire was designed to collect information on

Due to the small number of completed family composition, marital status and dura-

questionnaires received by the researcher, the tion of the parental relationship, the age and

decision was made to allow for the inclusion of gender of family members, level of education,

single-parent families. An analysis of variance employment, income and home language.

(ANOVA) revealed no statistically significant The familys socioeconomic status (SES) was

difference in scores between two-parent and determined using an adapted version of the

single-parent families with regard to the de- composite index derived by Riordan (cited in

pendent variable (family adaptation) (F (1, Tennant, 1996).

30) 2.5480, p 0.12). The dependent variable in this study is the

In total, 34 families participated in the familys level of adaptation, given the chronic

study: 16 from facility 1, 15 from facility 2 and stressful circumstances. This was measured us-

Resilience in Families / 349

ing the total score of the Family Attachment and original F-COPES) of .99 (McCubbin et al.,

Changeability Index (FACI8), adapted by Mc- 1996). The Cronbach alpha obtained in this

Cubbin, Thompson, and Elver. It is an ethni- study was .82.

cally sensitive measure of family adaptation The Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation

and functioning that consists of 16 items to be Scales (F-COPES) was developed by McCub-

answered on a five-point Likert-type scale. bin, Larsen, and Olson to distinguish prob-

FACI8 has two subscales, namely attachment lem-solving and behavioural strategies used by

and changeability. The internal reliability families during times of hardship. The

(Cronbachs alpha) of the total scale and the F-COPES consists of 30 items to be answered

two subscales varies between .73 and .80 (Mc- on a five-point Likert-type scale. The F-COPES

Cubbin et al., 1996), while the alpha values has five subscales, representing two dimen-

obtained in this study for the total scale and sions, namely internal and external coping

the attachment and changeability subscales strategies. Internal coping strategies are the

are .75, .79 and .85 respectively. use of resources within the family to manage

The Family Hardiness Index (FHI), devel- difficulties, while external coping strategies

oped by McCubbin, McCubbin, and Thomp- are the behaviours the family engages in to

son, was used to measure the characteristic of obtain resources outside the family system.

hardiness, which refers to the internal The F-COPES total scale has an internal reli-

strengths and durability of the family unit. ability coefficient (Cronbachs alpha) of .77

The FHI consists of 20 items to be answered and a test-retest reliability of .71 (McCubbin et

on a five-point Likert-type scale. The overall al., 1996). The internal reliability coefficients

internal reliability (Cronbachs alpha) of the for the subscales derived from the data in this

FHI is .82, while the internal reliabilities for study are .50 (passive evaluation); .72 (rede-

the three subscales (commitment, challenge fining the problem); .66 (seeking spiritual

and control) are .81, .80, and .65 respectively. support); .70 (looking for social support); and

The alpha values obtained in this study are .67 .53 (mobilising community resources).

for the total scale, and .62, .34 and .82 for the The Family Time and Routine Index (FTRI),

challenge, control and commitment subscales developed by McCubbin, McCubbin, and

respectively. The validity coefficients range Thompson, was used to explore the routines

from .20 to .23 for the variables of family and activities used by families, and to evaluate

satisfaction, time and routines, and flexibility the value placed by families on these practices.

(McCubbin et al., 1996). This measure consists of 30 Likert-type items,

The Social Support Index (SSI), developed by divided into eight subscales. The overall inter-

McCubbin, Patterson, and Glynn, determines nal reliability (Cronbachs alpha) of the FTRI

the extent to which families find support in is .88, while the validity coefficients range

the communities in which they live. This in- from .24 to .34 with regard to family bonding,

strument consists of 17 items to be answered family satisfaction, marital satisfaction, family

on a five-point Likert-type scale. The SSI has celebrations and family coherence (McCub-

an internal reliability of .82, a test-retest reli- bin et al., 1996). The reliability coefficients

ability of .83 and a validity coefficient of .40 obtained from the data in this study are .77 for

with the criterion of family wellbeing (McCub- the total scale; .48 for the parent-child togeth-

bin et al., 1996). A reliability analysis of the erness subscale; .61 for the couple-together-

data in this study yielded an internal reliability ness subscale; .33 for the child routines sub-

(Cronbach alpha) of .91. scale; .78 for the meals together subscale; .70

The Relative and Friend Support Index (RFSI), for the family time together subscale; .83 for

developed by McCubbin, Larsen, and Olson, the family chores routines subscale; .60 for the

consists of eight items to be answered on a relatives connection routines subscale; and .44

five-point Likert-type scale. The RFSI assesses for the family management routines subscale.

the degree to which families make use of The Family Problem Solving and Communica-

friend and relative support as a strategy to tion Scale (FPSC), developed by McCubbin,

manage stressors and strains. The internal re- McCubbin, and Thompson, consists of ten

liability (Cronbachs alpha) of the RFSI is .82, items to be answered on a four-point Likert-

with a validity coefficient (correlating with the type scale. The FPSC has two subscalesincen-

350 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-September 2010

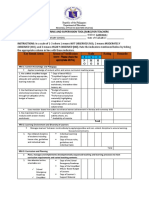

diary communication and affirming commu- TABLE 1

nication. The reliability (Cronbachs alpha) of

Pearson Correlations between Family Adaptation

the total scale is .89 and that of incendiary and Various Family Variables

communication and affirming communica-

tion is .78 and .86, respectively. The reliability Variable r p

coefficients obtained for this study are .83 for

incendiary communication, .87 for affirming Occupation classification of

communication, and .90 for the total scale. primary breadwinner .56 .01

The test-retest reliability of the subscales, as Age of autistic child .44 .02

well as of the total FPSC, is .86 (McCubbin et Socioeconomic status .53 .01

al., 1996). Social support (SSI) .45 .01

The qualitative measure comprised an Family problem solving and

communication (FPSC) .65 .01

open-ended question regarding the familys

Affirming communication .68 .01

perspective of the qualities that have helped

Incendiary communication -.57 .01

them to adapt to the presence of the autistic Family Hardiness Index (FHI) .76 .01

child. The question was: In your own words, Commitment .59 .01

what are the most important factors, or Challenge .71 .01

strengths, which have helped your family to Control .47 .01

adapt to living with your autistic child? The Family Crisis Oriented Personal

parents were thus required to respond in writ- Evaluation Scales

ing by giving their own personal account of (F-COPES)

factors that have facilitated their familys ad- Passive appraisal .59 .01

Family Time and Routine

aptation.

Index (FTRI) .44 .01

Parent-child togetherness .54 .01

Data Analysis Family time together .52 .01

In analysing the qualitative data, a process of

inductive reasoning was followed. Initially,

preliminary codes were assigned to the data, cant correlations were positive. Table 1 pro-

after which the codes were refined in order to vides a summary of the correlations found

better depict the data (Lacey & Luff, 2001). between the dependent variable (family adap-

These codes eventually become categories tation) and the various independent family

with which to identify various themes, which variables. Only the results that are significant

could then be used to report the results of the at a 1% level are presented.

qualitative aspect of the study (Pope, 2000). According to Table 1, statistically significant

In order to identify possible independent correlations exist between family adaptation

variables that may be associated with the de- and the following variables: the occupation

pendent variable (family adaptation), Pearson classification of the primary breadwinner, the

product-moment correlation coefficients were age of the autistic child, the socioeconomic

calculated. Multiple regression analysis was status of the family, social support, family

carried out in order to identify which combi- problem solving and communication, affirm-

nations of independent variables could best ing communication and incendiary communi-

predict family adaptation. cation (negative correlation), family hardiness

(commitment, challenge and control), the

coping strategy of passive appraisal, and family

Results

time and routines with the two aspects parent-

In the comparison of the FACI8 scores of child togetherness and family time together.

families with lower, middle and upper socio- In order to identify which combination of

economic status, the ANOVA analysis indi- independent variables would best predict the

cates that those of middle and upper socioeco- dependent variable (family adaptation), a

nomic status adapted better. Except for one best-subsets multiple regression analysis was

correlation (between family adaptation and carried out. Eighty-three percent of the vari-

incendiary communication), all other signifi- ance is explained by the equation (R .9099),

Resilience in Families / 351

with the identified factors being relative and peared to play a role in the familys adapta-

friend support (RFS total score) (p .02), tion, with families of middle and upper socio-

family problem solving and communication economic status being better adapted (see

(FPSC total score) (p .000), seeking spiri- Table 1). This may be accounted for by the

tual support as a coping style (p .15) and increased ability of middle-and upper-class

passive appraisal as a coping style (p .000). families to afford better treatment for their

autistic child. This finding is supported by

positive correlations between both socioeco-

Qualitative Results

nomic status and the occupation of the fami-

Thirty-three parents responded to the open- lys primary breadwinner with family adapta-

ended question and their responses were ana- tion.

lysed in order to identify categories of family A familys level of adaptation is associated

resilience. The following five broad categories with the extent to which families find support

emerged: (1) professional help/education in the communities in which they live (SSI

factors such as school and treatment pro- score). Social support is an important re-

grammes, knowledge of autism and advice source in alleviating the difficulties associated

from experts, (2) personal factors relating to with having a chronic stressor, such as an au-

the parentsthis category included factors like tistic child, in the home, and promoting suc-

maintaining a positive outlook, hope, commit- cessful adaptation (McCubbin et al., 1996;

ment and patience, (3) social support from Walsh, 2003). Social support has also been

family, friends, the community and parents of associated with positive family and child out-

other autistic children, (4) factors relating to comes in families with an autistic child (Rivers

the childtreating the child as normal, listen- & Stoneman, 2003). The results of the quali-

ing to the childs needs, empathy for the tative data support this finding.

child, recreational activities for the child, and Family adaptation is associated with the pat-

(5) factors relating to the family unit open terns of communication utilised by the family.

communication, strong parental relationship, It is enhanced by affirming communication,

having other children in the household, and while it declines when incendiary patterns of

working together as a family. communication are used (see Table 1). The

The single factors reported most often by quality of the communication in the family

the parents as facilitating the adaptation pro- provides a good indication of the degree to

cess following the diagnosis of an autistic child which families manage tension and strain and

were the school and treatment programmes obtain a satisfactory level of family function-

(52%), knowledge of autism (45%), accep- ing, adaptation and adjustment (McCubbin et

tance of the diagnosis (39%), support and al., 1996). Open communication was reported

involvement of extended family (39%), and in the qualitative data (n 4) as a factor that

faith in God (39%). helped families to adapt to the presence of an

autistic child.

Families with a supportive environment and

Discussion

a high degree of cohesion typically demon-

The aim of this study was to identify resilience strate higher degrees of commitment to and

factors in families living with an autistic child. help and support for one another. Such fam-

The parents reported that having other chil- ilies are also more likely to adapt successfully

dren in the home helped the family in the to the presence of a child with autism (Bristol,

adaptation process. This supports Powerss 1984). The parents in this study reported that

(2000) view that involving the siblings of chil- being committed to helping their autistic

dren with autism in the day-to-day care of the child, working together as a family (family

disabled child, as well as in the childs treat- hardiness, commitment, seeing crises as chal-

ment programmes (Howlin & Rutter, 1987), lenges), and making their children their top

leads to higher self-esteem and feelings of priority were all family strengths contributing

achievement in siblings and thus has a positive to better adaptation. Families who were will-

influence on the familys adaptation. ing to experience new things, to learn and to

The socioeconomic status of families ap- be innovative and active showed higher levels

352 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-September 2010

of family adaptation. Such flexibility is an es- dren. It enables the parents to take positive

sential process in family resilience (Walsh, steps towards helping their autistic child

2003). It involves the ability of families to (Rodrigue, Morgan & Geffken, 1990). In this

adapt to the stressor through the reorganisa- study, the parents highlighted their knowl-

tion of patterns of family interaction to fit the edge of autism as a positive factor resulting in

new demands faced by the family (Walsh). increased resilience. This coping strategy is

Families with an internal locus of control show adaptive, as it assists parents in learning how

higher levels of family functioning than those to help their child and prevents the use of

who perceive their lives as being shaped by maladaptive coping strategies (Rodrigue et

outside influences (hardiness control). This al.).

finding concurs with those obtained by Bris- Children with autism have a need for strict

tol, and Henderson and Vandenberg (1992), adherence to routines (Aarons & Gittens,

who found that people with an internal locus 1999). Any disruption to their known routines

of control are more likely to engage in behav- often leads to panic, fear or temper tantrums

iours to overcome the adverse effects of the (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). This aversion to

chronic stress of raising an autistic child, and changes in routines results in disruptions in

are thus more likely to achieve successful ad- family life, as the child may refuse to carry out

aptation. any activities unless their specific routine is

A healthy parental relationship leads to bet- followed (Mash & Wolfe, 2002). Parents of

ter adjustment in families with an autistic children with autism have emphasised the im-

child (Rodrigue et al., 1993). This is con- portance of routines in the process of success-

firmed by the parental reports in this study ful adaptation (Howlin & Rutter, 1987). Rou-

(see qualitative results). Powers (2000) argues tines assist parents in organising their time so

that parents should not feel that they must be as to make time for the autistic child, their

with their autistic child at all times and do other children, their spouse and themselves.

everything for him/her. Rather, the child McCubbin et al. (1996) have also identified

should be encouraged to develop skills that family routines as an important resource in

will enable him/her to function as indepen- the adaptation process. This is supported by

dently as possible. The parents in this study the findings of this study, which suggest a

shared this view and believed that making the positive correlation (see Table 1) between the

child as independent as possible was an im- routines and activities used by families and

portant step in the adaptation process. family adaptation. In terms of the qualitative

Families that make use of the internal cop- data, only two parents reported that sticking

ing strategy of passive appraisal appear to ex- to a basic routine was helpful in terms of

hibit higher levels of family adaptation (see achieving successful adaptation.

Table 1, as well as results of regression analy- This study found that families that empha-

sis). Passive evaluation involves accepting the sise family togetherness showed higher levels

stressful situation (the presence of the autistic of family adaptation (see Table 1, family to-

child) and not doing anything about it (Mc- getherness). The Resiliency Model of McCub-

Cubbin et al., 1996). This finding is interest- bin et al. (1996) highlights family celebrations

ing, as it would be logical to think that families and family time together as important re-

would achieve higher levels of adaptation by sources that facilitate family adaptation. It is

actively pursuing solutions to the stressful sit- also important for parents to have time to-

uation. The participants in this study might gether for themselves, without any children, as

have felt that they were doing all they could this allows them to invest in their relationship

for their autistic child and therefore resolved (Bristol, 1984; Powers, 2000). Time away from

to accept the situation. This finding supports the autistic child was reported as being impor-

that of Dyson et al. (1989) and Powers (2000), tant to the adaptation process by one parent

who state that acceptance of the child and in this study.

his/her disorder is an important factor con- Parents reported that maintaining a positive

tributing to adaptation to that child. outlook and remaining hopeful were factors

Information seeking is a coping strategy of- that helped them to adapt to having an autis-

ten employed by the parents of autistic chil- tic child (qualitative results). The importance

Resilience in Families / 353

of a positive outlook has been documented in understand resiliency factors specific to fami-

resilience theory. Families become resilient lies with an autistic child.

when they actively pursue solutions to their This study is characterised by a number of

problems, look beyond the hardships sur- limitations. Only 34 families took part, which

rounding their situation, and focus on making calls for caution in generalising the results to

the best of the options available to them all families with an autistic child in the home.

(Walsh, 2003). A further limitation is the geographic location

Faith in God was rated by the families in this of the participants. All the families participat-

study as an important factor contributing to ing in the study reside in the Cape Town

adaptation. Bristol (1984) found that belief in Metropolitan area, Western Cape Province,

God and/or adherence to clear moral stan- South Africa. This means that additional care

dards mediates the family hardships by giving should be taken in generalising the results,

meaning and purpose to the sacrifices they particularly with regard to families not resid-

make in caring for the autistic child. ing in urban areas. People from rural areas

are likely to experience greater difficulty in

accessing educational services and may have a

Conclusions lower socioeconomic status than the families

participating in this study.

The families that took part in this study were The findings of this study serve a dual role

privileged in the sense that they all had access in terms of their utility in facilitating family

to educational services for their autistic child. adaptation. Firstly, this study confirms that

The importance to the adaptation process and factors such as accessing social support, taking

of having access to schools and other commu- time away from their child, accepting the di-

nity resources is evident from previous re- agnosis, open emotional expression, family ac-

search (Bristol, 1984; Powers, 2000), in resil- tivities and routines, and family commitment

iency theory (McCubbin et al., 1996; Walsh, are all important resilience factors. As such,

2003), and in the results of this study (see they are beneficial for the childs wellbeing

Table 1). Due to the limitations of the sample and for successful family functioning. Sec-

because of their homogeneity in terms of ac- ondly, the findings may be used to provide

cess to educational services, it is proposed that both professionals and parents with insight

further research is undertaken to identify re- into how to create a family environment that

silience factors in families that do not have will benefit the autistic child, without being

access to such services. The majority of the detriment to the total family system.

families in this study was employed and had a

high socioeconomic status, which means that

it might be access to funds to invest in educa- References

tional services, rather than access to the ser-

Aarons, M., & Gittens, T. (1999). The handbook of

vices themselves, that is the true mediating

autism: a guide for parents and professionals. Lon-

factor. It is further recommended that fami- don: Routledge.

lies from lower socioeconomic backgrounds Autism Society of America. (2003). Retrieved March

be investigated in order to identify the factors 2, 2004 from http://www.autism-society.org/

that facilitate their adaptation to having an Autism South Africa. (2005). Autism South Africa.

autistic child. Retrieved August 7, 2005 from http://www.

Several family qualities described by the Re- autism-sa.org

silience Model of Stress, Adjustment and Ad- Blakeslee, S. (2003). Study shows increase in autism.

aptation (McCubbin et al., 1996) as being im- New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2006 from

portant in family adaptation were supported http://www.photius.com/feminocracy/autism.

html

by this study. These include social support and

Bristol, M. M. (1984). Family resources and success-

the mobilisation of community resources, ful adaptation to autistic children. In E. Schopler

open communication, and family hardiness, & G. B. Mesibov (Eds.). The effects of autism on the

including commitment and an internal locus family (pp. 289 310). New York: Plenum.

of control. The Resiliency Model, therefore, Cantwell, D. P., & Baker, L. (1984). Research con-

provides an effective contextual framework to cerning families of children with autism. In E.

354 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-September 2010

Schopler & G. B. Mesibov (Eds.), The effects of Pope, C. (2000). Analysing qualitative data-qualita-

autism on the family (pp. 41 63). New York: Ple- tive research in health care, part 2 education and

num. debate. British Medical Journal. Retrieved Novem-

Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) Pro- ber 16, 2004 from http://www.findarticles.com/

gramme. (2003). Retrieved March 16, 2004 from p/articles/mi_m0999/is_7227_320/ai_59110536

http://www.supreme.state.az.us/casa/training/ Powers, M. D. (2000). Children with autism: a parents

Autism/AutIndex.htm guide. Bethesda: Woodbine House.

Dyson, L. L., Edgar, E., & Crnic, K. (1989). Psycho- Rivers, J. W., & Stoneman, Z. (2003). Sibling rela-

logical predictors of adjustment by siblings of tionships when a child has autism: marital stress

developmentally disabled children. American Jour- and support coping. Journal of Autism and Develop-

nal on Mental Retardation, 94, 292302. mental Disorders, 33, 383394.

Hawley, D. R., & DeHaan, L. (1996). Toward a Rodrigue, J. R., Geffken, G. R., & Morgan, S. B.

definition of family resilience: integrating life (1993). Perceived competence and behavioural

span and family perspectives. Family Process, 35, adjustment of siblings of children with autism.

283298. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 23,

Henderson, D., & Vandenberg, B. (1992). Factors 665 674.

influencing adjustment in the families of autistic Rodrigue, J. R., Morgan, S. B., & Geffken, G. R.

children. Psychological Reports, 71, 167171. (1990). Families of autistic children: psychologi-

Howlin, P., & Rutter, M. (1987). Treatment of autistic cal functioning of mothers. Journal of Clinical

children. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Child Psychology, 19, 371379.

Lacey, A., & Luff, D. (2001). Trent focus for re- Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (2003). Synopsis of

search and development in primary health care: psychiatry: behavioural sciences/clinical psychiatry.

qualitative data analysis. Retrieved November Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkens.

16, 2004 from http://www.trentfocus.org.uk/ Sanders, J. L., & Morgan, S. (1997). Family stress

Resources/Qualitative%20Data%20Analysis.pdf and adjustment as perceived by parents of chil-

Mash, E. J., & Wolfe, D. A. (2002). Abnormal child dren with autism or Down syndrome: implications

psychology. Belmont: Wadsworth. for intervention. Child and Family Behaviour Ther-

McCubbin, M. A., & McCubbin, H. I. (1996). Resil- apy, 19(4), 1532.

iency in families: a conceptual model of family Tennant, A. J. (1996). Visual-motor perception: a cor-

adjustment and adaptation in response to stress relative study of specific measures for pre-school South

and crises. In H. I. McCubbin, A. I. Thompson, & African children. Unpublished Masters Thesis, Uni-

M. A. McCubbin (1996). Family assessment: resil- versity of Port Elizabeth, South Africa.

iency, coping and adaptationInventories for research Walsh, F. (2003). Normal family processes: growing di-

and practice (pp. 1 64). Madison: University of versity and complexity (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford

Wisconsin System. Press.

McCubbin, H. I., Thompson, A. I., & McCubbin,

M. A. (1996). Family assessment: resiliency, coping Received: 22 February 2009

and adaptationInventories for research and practice. Initial Acceptance: 30 April 2009

Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin System. Final Acceptance: 10 July 2009

Resilience in Families / 355

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Principles of EconomicsДокумент20 страницPrinciples of EconomicsRonald QuintoОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Geoarchaeology2012 Abstracts A-LДокумент173 страницыGeoarchaeology2012 Abstracts A-LPieroZizzaniaОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Internship Handbook (For Students 2220)Документ14 страницInternship Handbook (For Students 2220)kymiekwokОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Promise of Open EducationДокумент37 страницThe Promise of Open Educationjeremy_rielОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- 2017 Excerpt - Double BassДокумент5 страниц2017 Excerpt - Double BassJorge Arturo Preza Garduño100% (1)

- Informal Letters and EmailsДокумент7 страницInformal Letters and EmailsSimona SingiorzanОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Gerund and InfinitiveДокумент3 страницыGerund and InfinitivePAULA DANIELA BOTIA ORJUELAОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Indian Institute of Forest ManagmentДокумент10 страницIndian Institute of Forest ManagmentLabeeb HRtzОценок пока нет

- Global and Multicultural LiteracyДокумент5 страницGlobal and Multicultural LiteracyRYSHELLE PIAMONTEОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- КТП 11 кл New destinations 102Документ9 страницКТП 11 кл New destinations 102айгерим100% (2)

- Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning StudiesДокумент93 страницыEvaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studiesmario100% (3)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Anatomy Question Bank-1Документ40 страницAnatomy Question Bank-1Abd El-Rahman SalahОценок пока нет

- Cambridge Primary Progression Test - English As A Second Language 2016 Stage 3 - Paper 1 Question PDFДокумент11 страницCambridge Primary Progression Test - English As A Second Language 2016 Stage 3 - Paper 1 Question PDFTumwesigye robert100% (3)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Application For Admission: Azam MuhammadДокумент7 страницApplication For Admission: Azam MuhammadIshtiaq AzamОценок пока нет

- Monitoring and Supervision Tool (M&S) For TeachersДокумент3 страницыMonitoring and Supervision Tool (M&S) For TeachersJhanice Deniega EnconadoОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Bonafide Certificate: Head of Department SupervisorДокумент10 страницBonafide Certificate: Head of Department SupervisorSaumya mОценок пока нет

- Career Entry Development Profile (CEDP) - Transition Point 1 (May 2011)Документ3 страницыCareer Entry Development Profile (CEDP) - Transition Point 1 (May 2011)Glenn BillinghamОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Wsnake Prog 06a Withlogo 1Документ2 страницыWsnake Prog 06a Withlogo 1api-216697963Оценок пока нет

- Econ 251 PS4 SolutionsДокумент11 страницEcon 251 PS4 SolutionsPeter ShangОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences: Bayisa Bereka Negussie, Gebisa Bayisa OliksaДокумент6 страницInternational Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences: Bayisa Bereka Negussie, Gebisa Bayisa OliksaRaissa NoorОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Computer Systems Servicing NC II GuideДокумент4 страницыComputer Systems Servicing NC II GuideInnovator AdrianОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Implementation of Intrusion Detection Using Backpropagation AlgorithmДокумент5 страницImplementation of Intrusion Detection Using Backpropagation Algorithmpurushothaman sinivasanОценок пока нет

- Ucsp 11 Quarter 1 Week 2 Las 3Документ1 страницаUcsp 11 Quarter 1 Week 2 Las 3Clint JamesОценок пока нет

- Global Human Resource ManagementДокумент13 страницGlobal Human Resource ManagementTushar rana100% (1)

- Varun Sodhi Resume PDFДокумент1 страницаVarun Sodhi Resume PDFVarun SodhiОценок пока нет

- Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English DepartmentДокумент10 страницSarjana Pendidikan Degree in English DepartmentYanti TuyeОценок пока нет

- Unit 11 Science Nature Lesson PlanДокумент2 страницыUnit 11 Science Nature Lesson Planapi-590570447Оценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Axiology Study of Dental Implant Technology (Andi Askandar)Документ6 страницAxiology Study of Dental Implant Technology (Andi Askandar)Andi Askandar AminОценок пока нет

- 05basics of Veda Swaras and Recital - ChandasДокумент18 страниц05basics of Veda Swaras and Recital - ChandasFghОценок пока нет

- Understanding and Predicting Electronic Commerce Adoption An Extension of The Theory of Planned BehaviorДокумент30 страницUnderstanding and Predicting Electronic Commerce Adoption An Extension of The Theory of Planned BehaviorJingga NovebrezaОценок пока нет