Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Credit Transactions Batch 1 Cases 42 Pages FULL TEXT

Загружено:

Mizelle Alo0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

18 просмотров42 страницыCredit transactions cases full text -

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документCredit transactions cases full text -

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

18 просмотров42 страницыCredit Transactions Batch 1 Cases 42 Pages FULL TEXT

Загружено:

Mizelle AloCredit transactions cases full text -

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

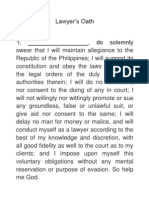

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 42

Republic of the Philippines Saura, Inc. was officially notified of the resolution on January 9, 1954.

The day before,

SUPREME COURT however, evidently having otherwise been informed of its approval, Saura, Inc. wrote a letter

Manila to RFC, requesting a modification of the terms laid down by it, namely: that in lieu of having

EN BANC China Engineers, Ltd. (which was willing to assume liability only to the extent of its stock

subscription with Saura, Inc.) sign as co-maker on the corresponding promissory notes, Saura,

G.R. No. L-24968 April 27, 1972 Inc. would put up a bond for P123,500.00, an amount equivalent to such subscription; and

SAURA IMPORT and EXPORT CO., INC., plaintiff-appellee, that Maria S. Roca would be substituted for Inocencia Arellano as one of the other co-

vs. makers, having acquired the latter's shares in Saura, Inc.

DEVELOPMENT BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES, defendant-appellant. In view of such request RFC approved Resolution No. 736 on February 4, 1954, designating of

Mabanag, Eliger and Associates and Saura, Magno and Associates for plaintiff-appellee. the members of its Board of Governors, for certain reasons stated in the resolution, "to

Jesus A. Avancea and Hilario G. Orsolino for defendant-appellant. reexamine all the aspects of this approved loan ... with special reference as to the advisability

of financing this particular project based on present conditions obtaining in the operations of

MAKALINTAL, J.:p jute mills, and to submit his findings thereon at the next meeting of the Board."

In Civil Case No. 55908 of the Court of First Instance of Manila, judgment was rendered on On March 24, 1954 Saura, Inc. wrote RFC that China Engineers, Ltd. had again agreed to act

June 28, 1965 sentencing defendant Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) to pay actual as co-signer for the loan, and asked that the necessary documents be prepared in accordance

and consequential damages to plaintiff Saura Import and Export Co., Inc. in the amount of with the terms and conditions specified in Resolution No. 145. In connection with the

P383,343.68, plus interest at the legal rate from the date the complaint was filed and reexamination of the project to be financed with the loan applied for, as stated in Resolution

attorney's fees in the amount of P5,000.00. The present appeal is from that judgment. No. 736, the parties named their respective committees of engineers and technical men to

In July 1953 the plaintiff (hereinafter referred to as Saura, Inc.) applied to the Rehabilitation meet with each other and undertake the necessary studies, although in appointing its own

Finance Corporation (RFC), before its conversion into DBP, for an industrial loan of committee Saura, Inc. made the observation that the same "should not be taken as an

P500,000.00, to be used as follows: P250,000.00 for the construction of a factory building acquiescence on (its) part to novate, or accept new conditions to, the agreement already)

(for the manufacture of jute sacks); P240,900.00 to pay the balance of the purchase price of entered into," referring to its acceptance of the terms and conditions mentioned in

the jute mill machinery and equipment; and P9,100.00 as additional working capital. Resolution No. 145.

Parenthetically, it may be mentioned that the jute mill machinery had already been On April 13, 1954 the loan documents were executed: the promissory note, with F.R. Halling,

purchased by Saura on the strength of a letter of credit extended by the Prudential Bank and representing China Engineers, Ltd., as one of the co-signers; and the corresponding deed of

Trust Co., and arrived in Davao City in July 1953; and that to secure its release without first mortgage, which was duly registered on the following April 17.

paying the draft, Saura, Inc. executed a trust receipt in favor of the said bank. It appears, however, that despite the formal execution of the loan agreement the

On January 7, 1954 RFC passed Resolution No. 145 approving the loan application for reexamination contemplated in Resolution No. 736 proceeded. In a meeting of the RFC Board

P500,000.00, to be secured by a first mortgage on the factory building to be constructed, the of Governors on June 10, 1954, at which Ramon Saura, President of Saura, Inc., was present,

land site thereof, and the machinery and equipment to be installed. Among the other terms it was decided to reduce the loan from P500,000.00 to P300,000.00. Resolution No. 3989 was

spelled out in the resolution were the following: approved as follows:

1. That the proceeds of the loan shall be utilized exclusively for the RESOLUTION No. 3989. Reducing the Loan Granted Saura Import & Export Co., Inc. under

following purposes: Resolution No. 145, C.S., from P500,000.00 to P300,000.00. Pursuant to Bd. Res. No. 736, c.s.,

For construction of factory building P250,000.00 authorizing the re-examination of all the various aspects of the loan granted the Saura

For payment of the balance of purchase Import & Export Co. under Resolution No. 145, c.s., for the purpose of financing the

price of machinery and equipment 240,900.00 manufacture of jute sacks in Davao, with special reference as to the advisability of financing

For working capital 9,100.00 this particular project based on present conditions obtaining in the operation of jute mills,

T O T A L P500,000.00 and after having heard Ramon E. Saura and after extensive discussion on the subject the

4. That Mr. & Mrs. Ramon E. Saura, Inocencia Arellano, Aniceto Caolboy and Gregoria Board, upon recommendation of the Chairman, RESOLVED that the loan granted the Saura

Estabillo and China Engineers, Ltd. shall sign the promissory notes jointly with the borrower- Import & Export Co. be REDUCED from P500,000 to P300,000 and that releases up to

corporation; P100,000 may be authorized as may be necessary from time to time to place the factory in

5. That release shall be made at the discretion of the Rehabilitation Finance Corporation, actual operation: PROVIDED that all terms and conditions of Resolution No. 145, c.s., not

subject to availability of funds, and as the construction of the factory buildings progresses, to inconsistent herewith, shall remain in full force and effect."

be certified to by an appraiser of this Corporation;" On June 19, 1954 another hitch developed. F.R. Halling, who had signed the promissory note

for China Engineers Ltd. jointly and severally with the other RFC that his company no longer

to of the loan and therefore considered the same as cancelled as far as it was concerned. A a) For the payment of the receipt for jute mill

follow-up letter dated July 2 requested RFC that the registration of the mortgage be machineries with the Prudential Bank &

withdrawn. Trust Company P250,000.00

In the meantime Saura, Inc. had written RFC requesting that the loan of P500,000.00 be (For immediate release)

granted. The request was denied by RFC, which added in its letter-reply that it was b) For the purchase of materials and equip-

"constrained to consider as cancelled the loan of P300,000.00 ... in view of a notification ... ment per attached list to enable the jute

from the China Engineers Ltd., expressing their desire to consider the loan insofar as they are mill to operate 182,413.91

concerned." c) For raw materials and labor 67,586.09

On July 24, 1954 Saura, Inc. took exception to the cancellation of the loan and informed RFC 1) P25,000.00 to be released on the open-

that China Engineers, Ltd. "will at any time reinstate their signature as co-signer of the note if ing of the letter of credit for raw jute

RFC releases to us the P500,000.00 originally approved by you.". for $25,000.00.

On December 17, 1954 RFC passed Resolution No. 9083, restoring the loan to the original 2) P25,000.00 to be released upon arrival

amount of P500,000.00, "it appearing that China Engineers, Ltd. is now willing to sign the of raw jute.

promissory notes jointly with the borrower-corporation," but with the following proviso: 3) P17,586.09 to be released as soon as the

That in view of observations made of the shortage and high cost of mill is ready to operate.

imported raw materials, the Department of Agriculture and Natural On January 25, 1955 RFC sent to Saura, Inc. the following reply:

Resources shall certify to the following: Dear Sirs:

1. That the raw materials needed by the borrower-corporation to carry This is with reference to your letter of January 21, 1955, regarding the release of

out its operation are available in the immediate vicinity; and your loan under consideration of P500,000. As stated in our letter of December 22,

2. That there is prospect of increased production thereof to provide 1954, the releases of the loan, if revived, are proposed to be made from time to

adequately for the requirements of the factory." time, subject to availability of funds towards the end that the sack factory shall be

The action thus taken was communicated to Saura, Inc. in a letter of RFC dated December 22, placed in actual operating status. We shall be able to act on your request for

1954, wherein it was explained that the certification by the Department of Agriculture and revised purpose and manner of releases upon re-appraisal of the securities offered

Natural Resources was required "as the intention of the original approval (of the loan) is to for the loan.

develop the manufacture of sacks on the basis of locally available raw materials." This point With respect to our requirement that the Department of Agriculture and Natural

is important, and sheds light on the subsequent actuations of the parties. Saura, Inc. does not Resources certify that the raw materials needed are available in the immediate

deny that the factory he was building in Davao was for the manufacture of bags from local vicinity and that there is prospect of increased production thereof to provide

raw materials. The cover page of its brochure (Exh. M) describes the project as a "Joint adequately the requirements of the factory, we wish to reiterate that the basis of

venture by and between the Mindanao Industry Corporation and the Saura Import and the original approval is to develop the manufacture of sacks on the basis of the

Export Co., Inc. to finance, manage and operate a Kenaf mill plant, to manufacture copra and locally available raw materials. Your statement that you will have to rely on the

corn bags, runners, floor mattings, carpets, draperies; out of 100% local raw materials, importation of jute and your request that we give you assurance that your company

principal kenaf." The explanatory note on page 1 of the same brochure states that, the will be able to bring in sufficient jute materials as may be necessary for the

venture "is the first serious attempt in this country to use 100% locally grown raw materials operation of your factory, would not be in line with our principle in approving the

notably kenafwhich is presently grown commercially in theIsland of Mindanao where the loan.

proposed jutemill is located ..." With the foregoing letter the negotiations came to a standstill. Saura, Inc. did not pursue the

This fact, according to defendant DBP, is what moved RFC to approve the loan application in matter further. Instead, it requested RFC to cancel the mortgage, and so, on June 17, 1955

the first place, and to require, in its Resolution No. 9083, a certification from the Department RFC executed the corresponding deed of cancellation and delivered it to Ramon F. Saura

of Agriculture and Natural Resources as to the availability of local raw materials to provide himself as president of Saura, Inc.

adequately for the requirements of the factory. Saura, Inc. itself confirmed the defendant's It appears that the cancellation was requested to make way for the registration of a

stand impliedly in its letter of January 21, 1955: (1) stating that according to a special study mortgage contract, executed on August 6, 1954, over the same property in favor of the

made by the Bureau of Forestry "kenaf will not be available in sufficient quantity this year or Prudential Bank and Trust Co., under which contract Saura, Inc. had up to December 31 of

probably even next year;" (2) requesting "assurances (from RFC) that my company and the same year within which to pay its obligation on the trust receipt heretofore mentioned. It

associates will be able to bring in sufficient jute materials as may be necessary for the full appears further that for failure to pay the said obligation the Prudential Bank and Trust Co.

operation of the jute mill;" and (3) asking that releases of the loan be made as follows: sued Saura, Inc. on May 15, 1955.

On January 9, 1964, ahnost 9 years after the mortgage in favor of RFC was cancelled at the obviously was in no position to comply with RFC's conditions. So instead of doing so and

request of Saura, Inc., the latter commenced the present suit for damages, alleging failure of insisting that the loan be released as agreed upon, Saura, Inc. asked that the mortgage be

RFC (as predecessor of the defendant DBP) to comply with its obligation to release the cancelled, which was done on June 15, 1955. The action thus taken by both parties was in the

proceeds of the loan applied for and approved, thereby preventing the plaintiff from nature cf mutual desistance what Manresa terms "mutuo disenso"1 which is a mode of

completing or paying contractual commitments it had entered into, in connection with its extinguishing obligations. It is a concept that derives from the principle that since mutual

jute mill project. agreement can create a contract, mutual disagreement by the parties can cause its

The trial court rendered judgment for the plaintiff, ruling that there was a perfected contract extinguishment.2

between the parties and that the defendant was guilty of breach thereof. The defendant The subsequent conduct of Saura, Inc. confirms this desistance. It did not protest against any

pleaded below, and reiterates in this appeal: (1) that the plaintiff's cause of action had alleged breach of contract by RFC, or even point out that the latter's stand was legally

prescribed, or that its claim had been waived or abandoned; (2) that there was no perfected unjustified. Its request for cancellation of the mortgage carried no reservation of whatever

contract; and (3) that assuming there was, the plaintiff itself did not comply with the terms rights it believed it might have against RFC for the latter's non-compliance. In 1962 it even

thereof. applied with DBP for another loan to finance a rice and corn project, which application was

We hold that there was indeed a perfected consensual contract, as recognized in Article 1934 disapproved. It was only in 1964, nine years after the loan agreement had been cancelled at

of the Civil Code, which provides: its own request, that Saura, Inc. brought this action for damages.All these circumstances

ART. 1954. An accepted promise to deliver something, by way of demonstrate beyond doubt that the said agreement had been extinguished by mutual

commodatum or simple loan is binding upon the parties, but the desistance and that on the initiative of the plaintiff-appellee itself.

commodatum or simple loan itself shall not be perferted until the With this view we take of the case, we find it unnecessary to consider and resolve the other

delivery of the object of the contract. issues raised in the respective briefs of the parties.

There was undoubtedly offer and acceptance in this case: the application of Saura, Inc. for a WHEREFORE, the judgment appealed from is reversed and the complaint dismissed, with

loan of P500,000.00 was approved by resolution of the defendant, and the corresponding costs against the plaintiff-appellee.

mortgage was executed and registered. But this fact alone falls short of resolving the basic Reyes, J.B.L., Actg. C.J., Zaldivar, Castro, Fernando, Teehankee, Barredo and Antonio, JJ.,

claim that the defendant failed to fulfill its obligation and the plaintiff is therefore entitled to concur.

recover damages. Makasiar, J., took no part.

It should be noted that RFC entertained the loan application of Saura, Inc. on the assumption

that the factory to be constructed would utilize locally grown raw materials, principally kenaf. Footnotes

There is no serious dispute about this. It was in line with such assumption that when RFC, by 1 8 Manresa, p. 294.

Resolution No. 9083 approved on December 17, 1954, restored the loan to the original 2 2 Castan, p. 560.

amount of P500,000.00. it imposed two conditions, to wit: "(1) that the raw materials needed Republic of the Philippines

by the borrower-corporation to carry out its operation are available in the immediate SUPREME COURT

vicinity; and (2) that there is prospect of increased production thereof to provide adequately Manila

for the requirements of the factory." The imposition of those conditions was by no means a EN BANC

deviation from the terms of the agreement, but rather a step in its implementation. There G.R. No. L-17474 October 25, 1962

was nothing in said conditions that contradicted the terms laid down in RFC Resolution No. REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee,

145, passed on January 7, 1954, namely "that the proceeds of the loan shall be vs.

utilized exclusively for the following purposes: for construction of factory building JOSE V. BAGTAS, defendant,

P250,000.00; for payment of the balance of purchase price of machinery and equipment FELICIDAD M. BAGTAS, Administratrix of the Intestate Estate left by the late Jose V.

P240,900.00; for working capital P9,100.00." Evidently Saura, Inc. realized that it could not Bagtas, petitioner-appellant.

meet the conditions required by RFC, and so wrote its letter of January 21, 1955, stating that D. T. Reyes, Liaison and Associates for petitioner-appellant.

local jute "will not be able in sufficient quantity this year or probably next year," and asking Office of the Solicitor General for plaintiff-appellee.

that out of the loan agreed upon the sum of P67,586.09 be released "for raw materials and PADILLA, J.:

labor." This was a deviation from the terms laid down in Resolution No. 145 and embodied in The Court of Appeals certified this case to this Court because only questions of law are

the mortgage contract, implying as it did a diversion of part of the proceeds of the loan to raised.

purposes other than those agreed upon. On 8 May 1948 Jose V. Bagtas borrowed from the Republic of the Philippines through the

When RFC turned down the request in its letter of January 25, 1955 the negotiations which Bureau of Animal Industry three bulls: a Red Sindhi with a book value of P1,176.46, a

had been going on for the implementation of the agreement reached an impasse. Saura, Inc. Bhagnari, of P1,320.56 and a Sahiniwal, of P744.46, for a period of one year from 8 May 1948

to 7 May 1949 for breeding purposes subject to a government charge of breeding fee of 10% memorandum receipt signed by the latter (Exhibit 2). That is why in its objection of 31

of the book value of the bulls. Upon the expiration on 7 May 1949 of the contract, the January 1959 to the appellant's motion to quash the writ of execution the appellee prays

borrower asked for a renewal for another period of one year. However, the Secretary of "that another writ of execution in the sum of P859.53 be issued against the estate of

Agriculture and Natural Resources approved a renewal thereof of only one bull for another defendant deceased Jose V. Bagtas." She cannot be held liable for the two bulls which

year from 8 May 1949 to 7 May 1950 and requested the return of the other two. On 25 already had been returned to and received by the appellee.

March 1950 Jose V. Bagtas wrote to the Director of Animal Industry that he would pay the The appellant contends that the Sahiniwal bull was accidentally killed during a raid by the

value of the three bulls. On 17 October 1950 he reiterated his desire to buy them at a value Huk in November 1953 upon the surrounding barrios of Hacienda Felicidad Intal, Baggao,

with a deduction of yearly depreciation to be approved by the Auditor General. On 19 Cagayan, where the animal was kept, and that as such death was due to force majeure she is

October 1950 the Director of Animal Industry advised him that the book value of the three relieved from the duty of returning the bull or paying its value to the appellee. The

bulls could not be reduced and that they either be returned or their book value paid not later contention is without merit. The loan by the appellee to the late defendant Jose V. Bagtas of

than 31 October 1950. Jose V. Bagtas failed to pay the book value of the three bulls or to the three bulls for breeding purposes for a period of one year from 8 May 1948 to 7 May

return them. So, on 20 December 1950 in the Court of First Instance of Manila the Republic 1949, later on renewed for another year as regards one bull, was subject to the payment by

of the Philippines commenced an action against him praying that he be ordered to return the the borrower of breeding fee of 10% of the book value of the bulls. The appellant contends

three bulls loaned to him or to pay their book value in the total sum of P3,241.45 and the that the contract was commodatum and that, for that reason, as the appellee retained

unpaid breeding fee in the sum of P199.62, both with interests, and costs; and that other just ownership or title to the bull it should suffer its loss due to force majeure. A contract

and equitable relief be granted in (civil No. 12818). of commodatum is essentially gratuitous.1 If the breeding fee be considered a compensation,

On 5 July 1951 Jose V. Bagtas, through counsel Navarro, Rosete and Manalo, answered that then the contract would be a lease of the bull. Under article 1671 of the Civil Code the lessee

because of the bad peace and order situation in Cagayan Valley, particularly in the barrio of would be subject to the responsibilities of a possessor in bad faith, because she had

Baggao, and of the pending appeal he had taken to the Secretary of Agriculture and Natural continued possession of the bull after the expiry of the contract. And even if the contract

Resources and the President of the Philippines from the refusal by the Director of Animal be commodatum, still the appellant is liable, because article 1942 of the Civil Code provides

Industry to deduct from the book value of the bulls corresponding yearly depreciation of 8% that a bailee in a contract ofcommodatum

from the date of acquisition, to which depreciation the Auditor General did not object, he . . . is liable for loss of the things, even if it should be through a fortuitous event:

could not return the animals nor pay their value and prayed for the dismissal of the (2) If he keeps it longer than the period stipulated . . .

complaint. (3) If the thing loaned has been delivered with appraisal of its value, unless there is

After hearing, on 30 July 1956 the trial court render judgment a stipulation exempting the bailee from responsibility in case of a fortuitous event;

. . . sentencing the latter (defendant) to pay the sum of P3,625.09 the total value of The original period of the loan was from 8 May 1948 to 7 May 1949. The loan of one bull was

the three bulls plus the breeding fees in the amount of P626.17 with interest on renewed for another period of one year to end on 8 May 1950. But the appellant kept and

both sums of (at) the legal rate from the filing of this complaint and costs. used the bull until November 1953 when during a Huk raid it was killed by stray bullets.

On 9 October 1958 the plaintiff moved ex parte for a writ of execution which the court Furthermore, when lent and delivered to the deceased husband of the appellant the bulls

granted on 18 October and issued on 11 November 1958. On 2 December 1958 granted an had each an appraised book value, to with: the Sindhi, at P1,176.46, the Bhagnari at

ex-parte motion filed by the plaintiff on November 1958 for the appointment of a special P1,320.56 and the Sahiniwal at P744.46. It was not stipulated that in case of loss of the bull

sheriff to serve the writ outside Manila. Of this order appointing a special sheriff, on 6 due to fortuitous event the late husband of the appellant would be exempt from liability.

December 1958, Felicidad M. Bagtas, the surviving spouse of the defendant Jose Bagtas who The appellant's contention that the demand or prayer by the appellee for the return of the

died on 23 October 1951 and as administratrix of his estate, was notified. On 7 January 1959 bull or the payment of its value being a money claim should be presented or filed in the

she file a motion alleging that on 26 June 1952 the two bull Sindhi and Bhagnari were intestate proceedings of the defendant who died on 23 October 1951, is not altogether

returned to the Bureau Animal of Industry and that sometime in November 1958 the third without merit. However, the claim that his civil personality having ceased to exist the trial

bull, the Sahiniwal, died from gunshot wound inflicted during a Huk raid on Hacienda court lost jurisdiction over the case against him, is untenable, because section 17 of Rule 3 of

Felicidad Intal, and praying that the writ of execution be quashed and that a writ of the Rules of Court provides that

preliminary injunction be issued. On 31 January 1959 the plaintiff objected to her motion. On After a party dies and the claim is not thereby extinguished, the court shall order,

6 February 1959 she filed a reply thereto. On the same day, 6 February, the Court denied her upon proper notice, the legal representative of the deceased to appear and to be

motion. Hence, this appeal certified by the Court of Appeals to this Court as stated at the substituted for the deceased, within a period of thirty (30) days, or within such

beginning of this opinion. time as may be granted. . . .

It is true that on 26 June 1952 Jose M. Bagtas, Jr., son of the appellant by the late defendant, and after the defendant's death on 23 October 1951 his counsel failed to comply with section

returned the Sindhi and Bhagnari bulls to Roman Remorin, Superintendent of the NVB 16 of Rule 3 which provides that

Station, Bureau of Animal Industry, Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya, as evidenced by a

Whenever a party to a pending case dies . . . it shall be the duty of his attorney to CARPIO, J.:

inform the court promptly of such death . . . and to give the name and residence of The Case

the executory administrator, guardian, or other legal representative of the Before us is a petition for review[1] of the 21 June 2000 Decision[2] and 14 December

deceased . . . . 2000 Resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 43129. The Court of Appeals set

The notice by the probate court and its publication in the Voz de Manila that Felicidad M. aside the 11 November 1996 decision[3] of the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch

Bagtas had been issue letters of administration of the estate of the late Jose Bagtas and that 81,[4] affirming the 15 December 1995 decision[5] of the Metropolitan Trial Court of Quezon

"all persons having claims for monopoly against the deceased Jose V. Bagtas, arising from City, Branch 31.[6]

contract express or implied, whether the same be due, not due, or contingent, for funeral The Antecedents

expenses and expenses of the last sickness of the said decedent, and judgment for monopoly In June 1979, petitioner Colito T. Pajuyo (Pajuyo) paid P400 to a certain Pedro Perez for

against him, to file said claims with the Clerk of this Court at the City Hall Bldg., Highway 54, the rights over a 250-square meter lot in Barrio Payatas, Quezon City. Pajuyo then

Quezon City, within six (6) months from the date of the first publication of this order, serving constructed a house made of light materials on the lot. Pajuyo and his family lived in the

a copy thereof upon the aforementioned Felicidad M. Bagtas, the appointed administratrix of house from 1979 to 7 December 1985.

the estate of the said deceased," is not a notice to the court and the appellee who were to be On 8 December 1985, Pajuyo and private respondent Eddie Guevarra (Guevarra)

notified of the defendant's death in accordance with the above-quoted rule, and there was executed a Kasunduan or agreement. Pajuyo, as owner of the house, allowed Guevarra to

no reason for such failure to notify, because the attorney who appeared for the defendant live in the house for free provided Guevarra would maintain the cleanliness and orderliness

was the same who represented the administratrix in the special proceedings instituted for of the house. Guevarra promised that he would voluntarily vacate the premises on Pajuyos

the administration and settlement of his estate. The appellee or its attorney or demand.

representative could not be expected to know of the death of the defendant or of the In September 1994, Pajuyo informed Guevarra of his need of the house and demanded

administration proceedings of his estate instituted in another court that if the attorney for that Guevarra vacate the house. Guevarra refused.

the deceased defendant did not notify the plaintiff or its attorney of such death as required Pajuyo filed an ejectment case against Guevarra with the Metropolitan Trial Court of

by the rule. Quezon City, Branch 31 (MTC).

As the appellant already had returned the two bulls to the appellee, the estate of the late In his Answer, Guevarra claimed that Pajuyo had no valid title or right of possession

defendant is only liable for the sum of P859.63, the value of the bull which has not been over the lot where the house stands because the lot is within the 150 hectares set aside by

returned to the appellee, because it was killed while in the custody of the administratrix of Proclamation No. 137 for socialized housing. Guevarra pointed out that from December 1985

his estate. This is the amount prayed for by the appellee in its objection on 31 January 1959 to September 1994, Pajuyo did not show up or communicate with him. Guevarra insisted

to the motion filed on 7 January 1959 by the appellant for the quashing of the writ of that neither he nor Pajuyo has valid title to the lot.

execution. On 15 December 1995, the MTC rendered its decision in favor of Pajuyo. The

Special proceedings for the administration and settlement of the estate of the deceased Jose dispositive portion of the MTC decision reads:

V. Bagtas having been instituted in the Court of First Instance of Rizal (Q-200), the money WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered for the plaintiff and against

judgment rendered in favor of the appellee cannot be enforced by means of a writ of defendant, ordering the latter to:

execution but must be presented to the probate court for payment by the appellant, the A) vacate the house and lot occupied by the defendant or any other person or

administratrix appointed by the court. persons claiming any right under him;

ACCORDINGLY, the writ of execution appealed from is set aside, without pronouncement as B) pay unto plaintiff the sum of THREE HUNDRED PESOS (P300.00) monthly as

to costs. reasonable compensation for the use of the premises starting from the last

Bengzon, C.J., Bautista Angelo, Labrador, Concepcion, Reyes, J.B.L., Paredes, Dizon, Regala demand;

and Makalintal, JJ., concur. C) pay plaintiff the sum of P3,000.00 as and by way of attorneys fees; and

Barrera, J., concurs in the result. D) pay the cost of suit.

SO ORDERED.[7]

Aggrieved, Guevarra appealed to the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 81

Footnotes (RTC).

1Article 1933 of the Civil Code. On 11 November 1996, the RTC affirmed the MTC decision. The dispositive portion of

FIRST DIVISION the RTC decision reads:

[G.R. No. 146364. June 3, 2004] WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Court finds no reversible error in the decision

COLITO T. PAJUYO, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and EDDIE GUEVARRA, respondents. appealed from, being in accord with the law and evidence presented, and the same is hereby

DECISION affirmed en toto.

SO ORDERED.[8] laws. The RTC declared that in an ejectment case, the only issue for resolution is material or

Guevarra received the RTC decision on 29 November 1996. Guevarra had only until 14 physical possession, not ownership.

December 1996 to file his appeal with the Court of Appeals. Instead of filing his appeal with The Ruling of the Court of Appeals

the Court of Appeals, Guevarra filed with the Supreme Court a Motion for Extension of Time The Court of Appeals declared that Pajuyo and Guevarra are squatters. Pajuyo and

to File Appeal by Certiorari Based on Rule 42 (motion for extension). Guevarra theorized that Guevarra illegally occupied the contested lot which the government owned.

his appeal raised pure questions of law. The Receiving Clerk of the Supreme Court received Perez, the person from whom Pajuyo acquired his rights, was also a squatter. Perez had

the motion for extension on 13 December 1996 or one day before the right to appeal no right or title over the lot because it is public land. The assignment of rights between Perez

expired. and Pajuyo, and the Kasunduan between Pajuyo and Guevarra, did not have any legal

On 3 January 1997, Guevarra filed his petition for review with the Supreme Court. effect. Pajuyo and Guevarra are in pari delicto or in equal fault. The court will leave them

On 8 January 1997, the First Division of the Supreme Court issued a where they are.

Resolution[9] referring the motion for extension to the Court of Appeals which has concurrent The Court of Appeals reversed the MTC and RTC rulings, which held that

jurisdiction over the case. The case presented no special and important matter for the the Kasunduan between Pajuyo and Guevarra created a legal tie akin to that of a landlord

Supreme Court to take cognizance of at the first instance. and tenant relationship. The Court of Appeals ruled that theKasunduan is not a lease contract

On 28 January 1997, the Thirteenth Division of the Court of Appeals issued a but a commodatum because the agreement is not for a price certain.

Resolution[10] granting the motion for extension conditioned on the timeliness of the filing of Since Pajuyo admitted that he resurfaced only in 1994 to claim the property, the

the motion. appellate court held that Guevarra has a better right over the property under Proclamation

On 27 February 1997, the Court of Appeals ordered Pajuyo to comment on Guevaras No. 137. President Corazon C. Aquino (President Aquino) issued Proclamation No. 137 on 7

petition for review. On 11 April 1997, Pajuyo filed his Comment. September 1987. At that time, Guevarra was in physical possession of the property. Under

On 21 June 2000, the Court of Appeals issued its decision reversing the RTC Article VI of the Code of Policies Beneficiary Selection and Disposition of Homelots and

decision. The dispositive portion of the decision reads: Structures in the National Housing Project (the Code), the actual occupant or caretaker of the

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the assailed Decision of the court a quo in Civil Case No. lot shall have first priority as beneficiary of the project. The Court of Appeals concluded that

Q-96-26943 is REVERSED and SET ASIDE; and it is hereby declared that the ejectment case Guevarra is first in the hierarchy of priority.

filed against defendant-appellant is without factual and legal basis. In denying Pajuyos motion for reconsideration, the appellate court debunked Pajuyos

SO ORDERED.[11] claim that Guevarra filed his motion for extension beyond the period to appeal.

Pajuyo filed a motion for reconsideration of the decision. Pajuyo pointed out that the The Court of Appeals pointed out that Guevarras motion for extension filed before the

Court of Appeals should have dismissed outright Guevarras petition for review because it was Supreme Court was stamped 13 December 1996 at 4:09 PM by the Supreme Courts Receiving

filed out of time. Moreover, it was Guevarras counsel and not Guevarra who signed the Clerk. The Court of Appeals concluded that the motion for extension bore a date, contrary to

certification against forum-shopping. Pajuyos claim that the motion for extension was undated. Guevarra filed the motion for

On 14 December 2000, the Court of Appeals issued a resolution denying Pajuyos extension on time on 13 December 1996 since he filed the motion one day before the

motion for reconsideration. The dispositive portion of the resolution reads: expiration of the reglementary period on 14 December 1996. Thus, the motion for extension

WHEREFORE, for lack of merit, the motion for reconsideration is hereby DENIED. No costs. properly complied with the condition imposed by the Court of Appeals in its 28 January 1997

SO ORDERED.[12] Resolution. The Court of Appeals explained that the thirty-day extension to file the petition

The Ruling of the MTC for review was deemed granted because of such compliance.

The MTC ruled that the subject of the agreement between Pajuyo and Guevarra is the The Court of Appeals rejected Pajuyos argument that the appellate court should have

house and not the lot. Pajuyo is the owner of the house, and he allowed Guevarra to use the dismissed the petition for review because it was Guevarras counsel and not Guevarra who

house only by tolerance. Thus, Guevarras refusal to vacate the house on Pajuyos demand signed the certification against forum-shopping.The Court of Appeals pointed out that Pajuyo

made Guevarras continued possession of the house illegal. did not raise this issue in his Comment. The Court of Appeals held that Pajuyo could not now

The Ruling of the RTC seek the dismissal of the case after he had extensively argued on the merits of the case.This

The RTC upheld the Kasunduan, which established the landlord and tenant relationship technicality, the appellate court opined, was clearly an afterthought.

between Pajuyo and Guevarra. The terms of the Kasunduan bound Guevarra to return The Issues

possession of the house on demand. Pajuyo raises the following issues for resolution:

The RTC rejected Guevarras claim of a better right under Proclamation No. 137, the WHETHER THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED OR ABUSED ITS AUTHORITY AND DISCRETION

Revised National Government Center Housing Project Code of Policies and other pertinent TANTAMOUNT TO LACK OF JURISDICTION:

laws. In an ejectment suit, the RTC has no power to decide Guevarras rights under these 1) in GRANTING, instead of denying, Private Respondents Motion for

an Extension of thirty days to file petition for review at the time

when there was no more period to extend as the decision of the on what the law is on a certain state of facts.[16] There is a question of fact when the doubt or

Regional Trial Court had already become final and executory. difference is on the truth or falsity of the facts alleged.[17]

2) in giving due course, instead of dismissing, private In his petition for review before this Court, Guevarra no longer disputed the

respondents Petition for Review even though the certification facts. Guevarras petition for review raised these questions: (1) Do ejectment cases pertain

against forum-shopping was signed only by counsel instead of by only to possession of a structure, and not the lot on which the structure stands? (2) Does a

petitioner himself. suit by a squatter against a fellow squatter constitute a valid case for ejectment? (3) Should a

3) in ruling that the Kasunduan voluntarily entered into by the Presidential Proclamation governing the lot on which a squatters structure stands be

parties was in fact a commodatum, instead of a Contract of Lease considered in an ejectment suit filed by the owner of the structure?

as found by the Metropolitan Trial Court and in holding that the These questions call for the evaluation of the rights of the parties under the law on

ejectment case filed against defendant-appellant is without legal ejectment and the Presidential Proclamation. At first glance, the questions Guevarra raised

and factual basis. appeared purely legal. However, some factual questions still have to be resolved because

4) in reversing and setting aside the Decision of the Regional Trial they have a bearing on the legal questions raised in the petition for review. These factual

Court in Civil Case No. Q-96-26943 and in holding that the parties matters refer to the metes and bounds of the disputed property and the application of

are in pari delicto being both squatters, therefore, illegal Guevarra as beneficiary of Proclamation No. 137.

occupants of the contested parcel of land. The Court of Appeals has the power to grant an extension of time to file a petition for

5) in deciding the unlawful detainer case based on the so-called Code review. In Lacsamana v. Second Special Cases Division of the Intermediate Appellate

of Policies of the National Government Center Housing Project Court,[18] we declared that the Court of Appeals could grant extension of time in appeals by

instead of deciding the same under the Kasunduan voluntarily petition for review. In Liboro v. Court of Appeals,[19] we clarified that the prohibition against

executed by the parties, the terms and conditions of which are granting an extension of time applies only in a case where ordinary appeal is perfected by a

the laws between themselves.[13] mere notice of appeal. The prohibition does not apply in a petition for review where the

The Ruling of the Court pleading needs verification. A petition for review, unlike an ordinary appeal, requires

The procedural issues Pajuyo is raising are baseless. However, we find merit in the preparation and research to present a persuasive position.[20] The drafting of the petition for

substantive issues Pajuyo is submitting for resolution. review entails more time and effort than filing a notice of appeal.[21] Hence, the Court of

Procedural Issues Appeals may allow an extension of time to file a petition for review.

Pajuyo insists that the Court of Appeals should have dismissed outright Guevarras In the more recent case of Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Court of

petition for review because the RTC decision had already become final and executory when Appeals,[22] we held that Liboros clarification of Lacsamana is consistent with the Revised

the appellate court acted on Guevarras motion for extension to file the petition. Pajuyo Internal Rules of the Court of Appeals and Supreme Court Circular No. 1-91. They all allow an

points out that Guevarra had only one day before the expiry of his period to appeal the RTC extension of time for filing petitions for review with the Court of Appeals. The extension,

decision. Instead of filing the petition for review with the Court of Appeals, Guevarra filed however, should be limited to only fifteen days save in exceptionally meritorious cases where

with this Court an undated motion for extension of 30 days to file a petition for review. This the Court of Appeals may grant a longer period.

Court merely referred the motion to the Court of Appeals. Pajuyo believes that the filing of A judgment becomes final and executory by operation of law. Finality of judgment

the motion for extension with this Court did not toll the running of the period to perfect the becomes a fact on the lapse of the reglementary period to appeal if no appeal is

appeal. Hence, when the Court of Appeals received the motion, the period to appeal had perfected.[23] The RTC decision could not have gained finality because the Court of Appeals

already expired. granted the 30-day extension to Guevarra.

We are not persuaded. The Court of Appeals did not commit grave abuse of discretion when it approved

Decisions of the regional trial courts in the exercise of their appellate jurisdiction are Guevarras motion for extension. The Court of Appeals gave due course to the motion for

appealable to the Court of Appeals by petition for review in cases involving questions of fact extension because it complied with the condition set by the appellate court in its resolution

or mixed questions of fact and law.[14] Decisions of the regional trial courts involving pure dated 28 January 1997. The resolution stated that the Court of Appeals would only give due

questions of law are appealable directly to this Court by petition for review.[15] These modes course to the motion for extension if filed on time. The motion for extension met this

of appeal are now embodied in Section 2, Rule 41 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure. condition.

Guevarra believed that his appeal of the RTC decision involved only questions of The material dates to consider in determining the timeliness of the filing of the motion

law. Guevarra thus filed his motion for extension to file petition for review before this Court for extension are (1) the date of receipt of the judgment or final order or resolution subject

on 14 December 1996. On 3 January 1997, Guevarra then filed his petition for review with of the petition, and (2) the date of filing of the motion for extension. [24] It is the date of the

this Court. A perusal of Guevarras petition for review gives the impression that the issues he filing of the motion or pleading, and not the date of execution, that determines the

raised were pure questions of law. There is a question of law when the doubt or difference is timeliness of the filing of that motion or pleading. Thus, even if the motion for extension

bears no date, the date of filing stamped on it is the reckoning point for determining the unlawful detainer, where the only issue for adjudication is the physical or material possession

timeliness of its filing. over the real property.[35]

Guevarra had until 14 December 1996 to file an appeal from the RTC In this case, what Guevarra raised before the courts was that he and Pajuyo are not the

decision. Guevarra filed his motion for extension before this Court on 13 December 1996, the owners of the contested property and that they are mere squatters. Will the defense that the

date stamped by this Courts Receiving Clerk on the motion for extension. Clearly, Guevarra parties to the ejectment case are not the owners of the disputed lot allow the courts to

filed the motion for extension exactly one day before the lapse of the reglementary period to renounce their jurisdiction over the case? The Court of Appeals believed so and held that it

appeal. would just leave the parties where they are since they are in pari delicto.

Assuming that the Court of Appeals should have dismissed Guevarras appeal on We do not agree with the Court of Appeals.

technical grounds, Pajuyo did not ask the appellate court to deny the motion for extension Ownership or the right to possess arising from ownership is not at issue in an action for

and dismiss the petition for review at the earliest opportunity. Instead, Pajuyo vigorously recovery of possession. The parties cannot present evidence to prove ownership or right to

discussed the merits of the case. It was only when the Court of Appeals ruled in Guevarras legal possession except to prove the nature of the possession when necessary to resolve the

favor that Pajuyo raised the procedural issues against Guevarras petition for review. issue of physical possession.[36] The same is true when the defendant asserts the absence of

A party who, after voluntarily submitting a dispute for resolution, receives an adverse title over the property. The absence of title over the contested lot is not a ground for the

decision on the merits, is estopped from attacking the jurisdiction of the court. [25] Estoppel courts to withhold relief from the parties in an ejectment case.

sets in not because the judgment of the court is a valid and conclusive adjudication, but The only question that the courts must resolve in ejectment proceedings is - who is

because the practice of attacking the courts jurisdiction after voluntarily submitting to it is entitled to the physical possession of the premises, that is, to the possession de facto and not

against public policy.[26] to the possession de jure.[37] It does not even matter if a partys title to the property is

In his Comment before the Court of Appeals, Pajuyo also failed to discuss Guevarras questionable,[38] or when both parties intruded into public land and their applications to own

failure to sign the certification against forum shopping. Instead, Pajuyo harped on Guevarras the land have yet to be approved by the proper government agency.[39] Regardless of the

counsel signing the verification, claiming that the counsels verification is insufficient since it is actual condition of the title to the property, the party in peaceable quiet possession shall not

based only on mere information. be thrown out by a strong hand, violence or terror.[40] Neither is the unlawful withholding of

A partys failure to sign the certification against forum shopping is different from the property allowed. Courts will always uphold respect for prior possession.

partys failure to sign personally the verification. The certificate of non-forum shopping must Thus, a party who can prove prior possession can recover such possession even against

be signed by the party, and not by counsel.[27] The certification of counsel renders the the owner himself.[41] Whatever may be the character of his possession, if he has in his favor

petition defective.[28] prior possession in time, he has the security that entitles him to remain on the property until

On the other hand, the requirement on verification of a pleading is a formal and not a a person with a better right lawfully ejects him.[42] To repeat, the only issue that the court has

jurisdictional requisite.[29] It is intended simply to secure an assurance that what are alleged to settle in an ejectment suit is the right to physical possession.

in the pleading are true and correct and not the product of the imagination or a matter of In Pitargue v. Sorilla,[43] the government owned the land in dispute. The government

speculation, and that the pleading is filed in good faith.[30] The party need not sign the did not authorize either the plaintiff or the defendant in the case of forcible entry case to

verification. A partys representative, lawyer or any person who personally knows the truth of occupy the land. The plaintiff had prior possession and had already introduced improvements

the facts alleged in the pleading may sign the verification. [31] on the public land. The plaintiff had a pending application for the land with the Bureau of

We agree with the Court of Appeals that the issue on the certificate against forum Lands when the defendant ousted him from possession. The plaintiff filed the action of

shopping was merely an afterthought. Pajuyo did not call the Court of Appeals attention to forcible entry against the defendant. The government was not a party in the case of forcible

this defect at the early stage of the proceedings.Pajuyo raised this procedural issue too late entry.

in the proceedings. The defendant questioned the jurisdiction of the courts to settle the issue of

Absence of Title over the Disputed Property will not Divest the Courts of Jurisdiction to possession because while the application of the plaintiff was still pending, title remained with

Resolve the Issue of Possession the government, and the Bureau of Public Lands had jurisdiction over the case. We disagreed

Settled is the rule that the defendants claim of ownership of the disputed property will with the defendant. We ruled that courts have jurisdiction to entertain ejectment suits even

not divest the inferior court of its jurisdiction over the ejectment case.[32] Even if the before the resolution of the application. The plaintiff, by priority of his application and of his

pleadings raise the issue of ownership, the court may pass on such issue to determine only entry, acquired prior physical possession over the public land applied for as against other

the question of possession, especially if the ownership is inseparably linked with the private claimants. That prior physical possession enjoys legal protection against other private

possession.[33] The adjudication on the issue of ownership is only provisional and will not bar claimants because only a court can take away such physical possession in an ejectment case.

an action between the same parties involving title to the land. [34] This doctrine is a necessary While the Court did not brand the plaintiff and the defendant in Pitargue[44] as

consequence of the nature of the two summary actions of ejectment, forcible entry and squatters, strictly speaking, their entry into the disputed land was illegal. Both the plaintiff

and defendant entered the public land without the owners permission. Title to the land

remained with the government because it had not awarded to anyone ownership of the Department to the exclusion of the courts? The answer to this question seems to us evident.

contested public land. Both the plaintiff and the defendant were in effect squatting on The Lands Department does not have the means to police public lands; neither does it have

government property. Yet, we upheld the courts jurisdiction to resolve the issue of the means to prevent disorders arising therefrom, or contain breaches of the peace among

possession even if the plaintiff and the defendant in the ejectment case did not have any title settlers; or to pass promptly upon conflicts of possession. Then its power is clearly limited to

over the contested land. disposition and alienation, and while it may decide conflicts of possession in order to make

Courts must not abdicate their jurisdiction to resolve the issue of physical possession proper award, the settlement of conflicts of possession which is recognized in the court

because of the public need to preserve the basic policy behind the summary actions of herein has another ultimate purpose, i.e., the protection of actual possessors and

forcible entry and unlawful detainer. The underlying philosophy behind ejectment suits is to occupants with a view to the prevention of breaches of the peace. The power to dispose

prevent breach of the peace and criminal disorder and to compel the party out of possession and alienate could not have been intended to include the power to prevent or settle

to respect and resort to the law alone to obtain what he claims is his.[45] The party deprived disorders or breaches of the peace among rival settlers or claimants prior to the final

of possession must not take the law into his own hands. [46] Ejectment proceedings are award. As to this, therefore, the corresponding branches of the Government must continue

summary in nature so the authorities can settle speedily actions to recover possession to exercise power and jurisdiction within the limits of their respective functions. The vesting

because of the overriding need to quell social disturbances.[47] of the Lands Department with authority to administer, dispose, and alienate public lands,

We further explained in Pitargue the greater interest that is at stake in actions for therefore, must not be understood as depriving the other branches of the Government of

recovery of possession. We made the following pronouncements in Pitargue: the exercise of the respective functions or powers thereon, such as the authority to stop

The question that is before this Court is: Are courts without jurisdiction to take cognizance of disorders and quell breaches of the peace by the police, the authority on the part of the

possessory actions involving these public lands before final award is made by the Lands courts to take jurisdiction over possessory actions arising therefrom not involving, directly

Department, and before title is given any of the conflicting claimants? It is one of utmost or indirectly, alienation and disposition.

importance, as there are public lands everywhere and there are thousands of settlers, Our attention has been called to a principle enunciated in American courts to the effect that

especially in newly opened regions. It also involves a matter of policy, as it requires the courts have no jurisdiction to determine the rights of claimants to public lands, and that until

determination of the respective authorities and functions of two coordinate branches of the the disposition of the land has passed from the control of the Federal Government, the

Government in connection with public land conflicts. courts will not interfere with the administration of matters concerning the same. (50 C. J.

Our problem is made simple by the fact that under the Civil Code, either in the old, which 1093-1094.) We have no quarrel with this principle. The determination of the respective

was in force in this country before the American occupation, or in the new, we have a rights of rival claimants to public lands is different from the determination of who has the

possessory action, the aim and purpose of which is the recovery of the physical possession of actual physical possession or occupation with a view to protecting the same and preventing

real property, irrespective of the question as to who has the title thereto. Under the Spanish disorder and breaches of the peace. A judgment of the court ordering restitution of the

Civil Code we had the accion interdictal, a summary proceeding which could be brought possession of a parcel of land to the actual occupant, who has been deprived thereof by

within one year from dispossession (Roman Catholic Bishop of Cebu vs. Mangaron, 6 Phil. another through the use of force or in any other illegal manner, can never be prejudicial

286, 291); and as early as October 1, 1901, upon the enactment of the Code of Civil interference with the disposition or alienation of public lands. On the other hand, if courts

Procedure (Act No. 190 of the Philippine Commission) we implanted the common law action were deprived of jurisdiction of cases involving conflicts of possession, that threat of

of forcible entry (section 80 of Act No. 190), the object of which has been stated by this Court judicial action against breaches of the peace committed on public lands would be

to be to prevent breaches of the peace and criminal disorder which would ensue from the eliminated, and a state of lawlessness would probably be produced between applicants,

withdrawal of the remedy, and the reasonable hope such withdrawal would create that occupants or squatters, where force or might, not right or justice, would rule.

some advantage must accrue to those persons who, believing themselves entitled to the It must be borne in mind that the action that would be used to solve conflicts of possession

possession of property, resort to force to gain possession rather than to some appropriate between rivals or conflicting applicants or claimants would be no other than that of forcible

action in the court to assert their claims. (Supia and Batioco vs. Quintero and Ayala, 59 Phil. entry. This action, both in England and the United States and in our jurisdiction, is a summary

312, 314.) So before the enactment of the first Public Land Act (Act No. 926) the action of and expeditious remedy whereby one in peaceful and quiet possession may recover the

forcible entry was already available in the courts of the country. So the question to be possession of which he has been deprived by a stronger hand, by violence or terror; its

resolved is, Did the Legislature intend, when it vested the power and authority to alienate ultimate object being to prevent breach of the peace and criminal disorder. (Supia and

and dispose of the public lands in the Lands Department, to exclude the courts from Batioco vs. Quintero and Ayala, 59 Phil. 312, 314.) The basis of the remedy is mere

entertaining the possessory action of forcible entry between rival claimants or occupants of possession as a fact, of physical possession, not a legal possession. (Mediran vs. Villanueva,

any land before award thereof to any of the parties? Did Congress intend that the lands 37 Phil. 752.) The title or right to possession is never in issue in an action of forcible entry; as

applied for, or all public lands for that matter, be removed from the jurisdiction of the judicial a matter of fact, evidence thereof is expressly banned, except to prove the nature of the

Branch of the Government, so that any troubles arising therefrom, or any breaches of the possession. (Second 4, Rule 72, Rules of Court.) With this nature of the action in mind, by no

peace or disorders caused by rival claimants, could be inquired into only by the Lands stretch of the imagination can conclusion be arrived at that the use of the remedy in the

courts of justice would constitute an interference with the alienation, disposition, and properties usurped from them. Courts should not leave squatters to their own devices in

control of public lands. To limit ourselves to the case at bar can it be pretended at all that its cases involving recovery of possession.

result would in any way interfere with the manner of the alienation or disposition of the land Possession is the only Issue for Resolution in an Ejectment Case

contested? On the contrary, it would facilitate adjudication, for the question of priority of The case for review before the Court of Appeals was a simple case of ejectment. The

possession having been decided in a final manner by the courts, said question need no longer Court of Appeals refused to rule on the issue of physical possession. Nevertheless, the

waste the time of the land officers making the adjudication or award. (Emphasis ours) appellate court held that the pivotal issue in this case is who between Pajuyo and Guevarra

The Principle of Pari Delicto is not Applicable to Ejectment Cases has the priority right as beneficiary of the contested land under Proclamation No.

The Court of Appeals erroneously applied the principle of pari delicto to this case. 137.[54] According to the Court of Appeals, Guevarra enjoys preferential right under

Articles 1411 and 1412 of the Civil Code[48] embody the principle of pari delicto. We Proclamation No. 137 because Article VI of the Code declares that the actual occupant or

explained the principle of pari delicto in these words: caretaker is the one qualified to apply for socialized housing.

The rule of pari delicto is expressed in the maxims ex dolo malo non eritur actio and in pari The ruling of the Court of Appeals has no factual and legal basis.

delicto potior est conditio defedentis. The law will not aid either party to an illegal agreement. First. Guevarra did not present evidence to show that the contested lot is part of a

It leaves the parties where it finds them.[49] relocation site under Proclamation No. 137. Proclamation No. 137 laid down the metes and

The application of the pari delicto principle is not absolute, as there are exceptions to bounds of the land that it declared open for disposition to bona fide residents.

its application. One of these exceptions is where the application of the pari delicto rule would The records do not show that the contested lot is within the land specified by

violate well-established public policy.[50] Proclamation No. 137. Guevarra had the burden to prove that the disputed lot is within the

In Drilon v. Gaurana,[51] we reiterated the basic policy behind the summary actions of coverage of Proclamation No. 137. He failed to do so.

forcible entry and unlawful detainer. We held that: Second. The Court of Appeals should not have given credence to Guevarras

It must be stated that the purpose of an action of forcible entry and detainer is that, unsubstantiated claim that he is the beneficiary of Proclamation No. 137. Guevarra merely

regardless of the actual condition of the title to the property, the party in peaceable quiet alleged that in the survey the project administrator conducted, he and not Pajuyo appeared

possession shall not be turned out by strong hand, violence or terror. In affording this as the actual occupant of the lot.

remedy of restitution the object of the statute is to prevent breaches of the peace and There is no proof that Guevarra actually availed of the benefits of Proclamation No.

criminal disorder which would ensue from the withdrawal of the remedy, and the reasonable 137. Pajuyo allowed Guevarra to occupy the disputed property in 1985. President Aquino

hope such withdrawal would create that some advantage must accrue to those persons who, signed Proclamation No. 137 into law on 11 March 1986. Pajuyo made his earliest demand

believing themselves entitled to the possession of property, resort to force to gain for Guevarra to vacate the property in September 1994.

possession rather than to some appropriate action in the courts to assert their claims. This is During the time that Guevarra temporarily held the property up to the time that

the philosophy at the foundation of all these actions of forcible entry and detainer which are Proclamation No. 137 allegedly segregated the disputed lot, Guevarra never applied as

designed to compel the party out of possession to respect and resort to the law alone to beneficiary of Proclamation No. 137. Even when Guevarra already knew that Pajuyo was

obtain what he claims is his.[52] reclaiming possession of the property, Guevarra did not take any step to comply with the

Clearly, the application of the principle of pari delicto to a case of ejectment between requirements of Proclamation No. 137.

squatters is fraught with danger. To shut out relief to squatters on the ground of pari Third. Even assuming that the disputed lot is within the coverage of Proclamation No.

delicto would openly invite mayhem and lawlessness. A squatter would oust another 137 and Guevarra has a pending application over the lot, courts should still assume

squatter from possession of the lot that the latter had illegally occupied, emboldened by the jurisdiction and resolve the issue of possession. However, the jurisdiction of the courts would

knowledge that the courts would leave them where they are. Nothing would then stand in be limited to the issue of physical possession only.

the way of the ousted squatter from re-claiming his prior possession at all cost. In Pitargue,[55] we ruled that courts have jurisdiction over possessory actions involving

Petty warfare over possession of properties is precisely what ejectment cases or public land to determine the issue of physical possession. The determination of the

actions for recovery of possession seek to prevent.[53] Even the owner who has title over the respective rights of rival claimants to public land is, however, distinct from the determination

disputed property cannot take the law into his own hands to regain possession of his of who has the actual physical possession or who has a better right of physical

property. The owner must go to court. possession.[56] The administrative disposition and alienation of public lands should be

Courts must resolve the issue of possession even if the parties to the ejectment suit are threshed out in the proper government agency.[57]

squatters. The determination of priority and superiority of possession is a serious and urgent The Court of Appeals determination of Pajuyo and Guevarras rights under Proclamation

matter that cannot be left to the squatters to decide. To do so would make squatters receive No. 137 was premature. Pajuyo and Guevarra were at most merely potential beneficiaries of

better treatment under the law. The law restrains property owners from taking the law into the law. Courts should not preempt the decision of the administrative agency mandated by

their own hands. However, the principle of pari delicto as applied by the Court of Appeals law to determine the qualifications of applicants for the acquisition of public lands. Instead,

would give squatters free rein to dispossess fellow squatters or violently retake possession of

courts should expeditiously resolve the issue of physical possession in ejectment cases to obligated him to maintain the property in good condition. The imposition of this obligation

prevent disorder and breaches of peace.[58] makes the Kasunduan a contract different from a commodatum. The effects of

Pajuyo is Entitled to Physical Possession of the Disputed Property the Kasunduan are also different from that of a commodatum. Case law on ejectment has

Guevarra does not dispute Pajuyos prior possession of the lot and ownership of the treated relationship based on tolerance as one that is akin to a landlord-tenant relationship

house built on it. Guevarra expressly admitted the existence and due execution of where the withdrawal of permission would result in the termination of the lease. [69] The

the Kasunduan. The Kasunduan reads: tenants withholding of the property would then be unlawful.This is settled jurisprudence.

Ako, si COL[I]TO PAJUYO, may-ari ng bahay at lote sa Bo. Payatas, Quezon City, ay nagbibigay Even assuming that the relationship between Pajuyo and Guevarra is one

pahintulot kay G. Eddie Guevarra, na pansamantalang manirahan sa nasabing bahay at lote of commodatum, Guevarra as bailee would still have the duty to turn over possession of the

ng walang bayad. Kaugnay nito, kailangang panatilihin nila ang kalinisan at kaayusan ng property to Pajuyo, the bailor. The obligation to deliver or to return the thing received

bahay at lote. attaches to contracts for safekeeping, or contracts of commission, administration

Sa sandaling kailangan na namin ang bahay at lote, silay kusang aalis ng walang reklamo. and commodatum.[70] These contracts certainly involve the obligation to deliver or return the

Based on the Kasunduan, Pajuyo permitted Guevarra to reside in the house and lot free thing received.[71]

of rent, but Guevarra was under obligation to maintain the premises in good condition. Guevarra turned his back on the Kasunduan on the sole ground that like him, Pajuyo is

Guevarra promised to vacate the premises on Pajuyos demand but Guevarra broke his also a squatter. Squatters, Guevarra pointed out, cannot enter into a contract involving the

promise and refused to heed Pajuyos demand to vacate. land they illegally occupy. Guevarra insists that the contract is void.

These facts make out a case for unlawful detainer. Unlawful detainer involves the Guevarra should know that there must be honor even between squatters. Guevarra

withholding by a person from another of the possession of real property to which the latter is freely entered into the Kasunduan. Guevarra cannot now impugn the Kasunduan after he

entitled after the expiration or termination of the formers right to hold possession under a had benefited from it. The Kasunduan binds Guevarra.

contract, express or implied.[59] The Kasunduan is not void for purposes of determining who between Pajuyo and

Where the plaintiff allows the defendant to use his property by tolerance without any Guevarra has a right to physical possession of the contested property. The Kasunduan is the

contract, the defendant is necessarily bound by an implied promise that he will vacate on undeniable evidence of Guevarras recognition of Pajuyos better right of physical possession.

demand, failing which, an action for unlawful detainer will lie.[60] The defendants refusal to Guevarra is clearly a possessor in bad faith. The absence of a contract would not yield a

comply with the demand makes his continued possession of the property unlawful. [61] The different result, as there would still be an implied promise to vacate.

status of the defendant in such a case is similar to that of a lessee or tenant whose term of Guevarra contends that there is a pernicious evil that is sought to be avoided, and that

lease has expired but whose occupancy continues by tolerance of the owner.[62] is allowing an absentee squatter who (sic) makes (sic) a profit out of his illegal

This principle should apply with greater force in cases where a contract embodies the act.[72] Guevarra bases his argument on the preferential right given to the actual occupant or

permission or tolerance to use the property. The Kasunduan expressly articulated Pajuyos caretaker under Proclamation No. 137 on socialized housing.

forbearance. Pajuyo did not require Guevarra to pay any rent but only to maintain the house We are not convinced.

and lot in good condition. Guevarra expressly vowed in the Kasunduan that he would vacate Pajuyo did not profit from his arrangement with Guevarra because Guevarra stayed in

the property on demand. Guevarras refusal to comply with Pajuyos demand to vacate made the property without paying any rent. There is also no proof that Pajuyo is a professional

Guevarras continued possession of the property unlawful. squatter who rents out usurped properties to other squatters. Moreover, it is for the proper

We do not subscribe to the Court of Appeals theory that the Kasunduan is one government agency to decide who between Pajuyo and Guevarra qualifies for socialized

of commodatum. housing. The only issue that we are addressing is physical possession.

In a contract of commodatum, one of the parties delivers to another something not Prior possession is not always a condition sine qua non in ejectment.[73] This is one of

consumable so that the latter may use the same for a certain time and return it. [63] An the distinctions between forcible entry and unlawful detainer.[74] In forcible entry, the

essential feature of commodatum is that it is gratuitous. Another feature of commodatum is plaintiff is deprived of physical possession of his land or building by means of force,

that the use of the thing belonging to another is for a certain period. [64] Thus, the bailor intimidation, threat, strategy or stealth. Thus, he must allege and prove prior

cannot demand the return of the thing loaned until after expiration of the period stipulated, possession.[75] But in unlawful detainer, the defendant unlawfully withholds possession after

or after accomplishment of the use for which the commodatum is constituted.[65] If the bailor the expiration or termination of his right to possess under any contract, express or implied.

should have urgent need of the thing, he may demand its return for temporary use. [66] If the In such a case, prior physical possession is not required.[76]

use of the thing is merely tolerated by the bailor, he can demand the return of the thing at Pajuyos withdrawal of his permission to Guevarra terminated

will, in which case the contractual relation is called a precarium.[67] Under the Civil the Kasunduan. Guevarras transient right to possess the property ended as well. Moreover, it

Code, precarium is a kind of commodatum.[68] was Pajuyo who was in actual possession of the property because Guevarra had to seek

The Kasunduan reveals that the accommodation accorded by Pajuyo to Guevarra was Pajuyos permission to temporarily hold the property and Guevarra had to follow the

not essentially gratuitous. While the Kasunduan did not require Guevarra to pay rent, it

conditions set by Pajuyo in the Kasunduan. Control over the property still rested with Pajuyo We sustain the P300 monthly rentals the MTC and RTC assessed against

and this is evidence of actual possession. Guevarra. Guevarra did not dispute this factual finding of the two courts. We find the

Pajuyos absence did not affect his actual possession of the disputed property. amount reasonable compensation to Pajuyo. The P300 monthly rental is counted from the

Possession in the eyes of the law does not mean that a man has to have his feet on every last demand to vacate, which was on 16 February 1995.

square meter of the ground before he is deemed in possession.[77] One may acquire WHEREFORE, we GRANT the petition. The Decision dated 21 June 2000 and Resolution