Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Serious Morbidity Associated With Misuse of Over-The-counter

Загружено:

IslamАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Serious Morbidity Associated With Misuse of Over-The-counter

Загружено:

IslamАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

M E D I C I N E A N D TH E C O M MU N I TY

Serious morbidity associated with misuse of over-the-counter

codeine–ibuprofen analgesics: a series of 27 cases

Matthew Y Frei, Suzanne Nielsen, Malcolm D H Dobbin and Claire L Tobin

W hile extensive overseas evidence

is accumulating about the non-

medical use of prescription

opioids1-5 and the serious consequences of

such use,1-4,6,7 literature on non-prescribed

ABSTRACT

Objective: To investigate morbidity related to misuse of over-the-counter (OTC)

codeine–ibuprofen analgesics.

Design and setting: Prospective case series collected from Victorian hospital-based

or over-the-counter (OTC) opioids is mainly addiction medicine specialists between May 2005 and December 2008.

confined to case descriptions.8-11 This is Main outcome measures: Morbidity associated with codeine–ibuprofen misuse.

despite Results: Twenty-seven patients with serious morbidity were included, mainly with

Theindications, such ofas Australia

Medical Journal in the 2007

ISSN:

Australian National Drug Strategy House- gastrointestinal haemorrhage and opioid dependence. The patients were taking mean

0025-729X 6 September 2010 193 5 294-

hold Survey,

296 that over half a million Austral- daily doses of 435–602 mg of codeine phosphate and 6800–9400 mg ibuprofen. Most

ians ©The

used Medical

pain killers

Journalfor non-medical

of Australia 2010 patients had no previous history of substance use disorder. The main treatment was

12

www.mja.com.au opioid substitution treatment with buprenorphine–naloxone or methadone.

purposes, the third most common cate-

gory Medicine and theuse

of substance community

in Australia after Conclusions: Although codeine can be considered a relatively weak opioid analgesic,

cannabis and ecstasy. it is nevertheless addictive, and the significant morbidity and specific patient

Although codeine is often described as a characteristics associated with overuse of codeine–ibuprofen analgesics support further

weak opioid analgesic, codeine dependence is awareness, investigation and monitoring of OTC codeine–ibuprofen analgesic use.

a well recognised complication of long-term

MJA 2010; 193: 294–296

use.13-15 Codeine-containing medications are

available in Australia either through a doctor’s

prescription or in combination OTC formula- the patient; the minimum and maximum 10 cases of each. Three patients had

tions with simple analgesics. Substance- doses of OTC codeine–ibuprofen consumed; hypokalaemia and one patient required

dependent individuals who escalate their dose the patient’s drug use history; the main brand dialysis. These complications (hypokalae-

of medication above recommended amounts of OTC codeine–ibuprofen used; the drug mia and renal failure) are associated with

are at risk of harm from the accompanying source; a description of the patient’s presenta-

simple analgesic,16 including toxicity from tion; and patient outcomes.

1 Characteristics of the 27 patients

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs Details of the study and the case report

treated for misuse of OTC

(NSAIDs)17-19 such as ibuprofen. form were disseminated to participating

codeine–ibuprofen analgesics

We collected data on a series of 27 patients addiction medicine clinicians. Addiction

as a response to clinical interest in anecdotal medicine specialists completed all but two of Case characteristics n

reports of misuse of an OTC pharmaceutical the case report forms, and two forms were

Male 14

product containing codeine phosphate received from specialist addiction medicine

Age (years)

12.8 mg and ibuprofen 200 mg. clinical nurse consultants. Four separate

addiction services, from southern, eastern, 20–29 8

western and central metropolitan Melbourne 30–39 7

METHODS

contributed cases. ⭓ 40 9

Clinicians in a network of specialist addiction Descriptive analysis was conducted with History of intravenous 10

treatment services (the Victorian Addiction SPSS, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, drug use

Inter-hospital Liaison Association) in several USA). The study was approved by the Victo- Reported only using 14

Victorian health regions collected and submit- rian Department of Human Services Human pharmaceutical

ted the cases for this study. These services Research Ethics Committee. opioids

cover nine hospitals across Melbourne metro-

Reported no other 15

politan regions and rural Victoria. They range substance use with

from small, specialist consultation–liaison RESULTS

OTC codeine

teams to large, multidisciplinary suites, Of the 27 patients in the cases collected, about

Reported prolonged 26

including alcohol and other drug outpatient half were male (sex was not reported in one codeine use

treatment services. The 27 patients either case).

Anaemia 12

presented for treatment of opioid depend- Most of the sample (17) did not report a

ence, or were inpatients referred to hospital history of injection drug misuse. Just over half Codeine use Mean

addiction medicine services between May the patients (14) reported only using pharma- OTC codeine 3.6 years

2005 and December 2008. ceutical drugs (Box 1). Three patients had a use (range) (2 days – 11 years)

A case report form was used to collect history of alcohol use disorder. Minimum daily 34 tablets (10–72)

standardised information about OTC Opioid dependence and gastrointestinal dose (range)

codeine–ibuprofen cases. The form included complications (attributed to ibuprofen) OTC = over the counter. ◆

the following details: the harm experienced by were the most common morbidities, with

294 MJA • Volume 193 Number 5 • 6 September 2010

M E D I C I N E A N D TH E C O M MU N I TY

2 Summary of presentations and outcomes for the 27 patients treated for misuse of OTC codeine–ibuprofen

Daily intake

Patient presentation (tablets) Outcome/management

Mainly GI medical complications

GI haemorrhage, perforated duodenal ulcer 48 Treated with buprenorphine–naloxone

Persistent vomiting, GI haemorrhage requiring gastrectomy 20 Discharged on slow-release oxycodone

Admitted with duodenal haemorrhage, anaemia and hypokalaemia 24 Opioid withdrawal treated; LTFU

Referred while an inpatient with haematemesis, anaemia (Hb 55 g/L); 20–40 Treated with pantoprazole; referred to

initiated use for chronic back pain community AOD clinic

Multiple ED presentations with complications of ibuprofen-related 48–72 Stabilised on buprenorphine

anaemia and haematemesis

GI haemorrhage, perforated peptic ulcer 50 Stabilised on methadone solution

Second GI haemorrhage in 2 years; 24–48 Treated with buprenorphine

initiated use for back pain and escalated dose

Mainly other medical complications

Acute renal failure, GI haemorrhages; required transfusion and ICU admission 24–48 Treated with methadone

Hypokalaemia; initiated use for arm pain 24–48 Admitted to ICU and stabilised

Mainly medical complications and dependence or overdose

Opioid-dependent; initiated use for back pain. Presented for detoxification, hypokalaemic 48–100 Treated with buprenorphine

at admission

Admitted for opioid withdrawal; mild anaemia (Hb 99 g/L) 72 Stabilised on buprenorphine–naloxone

Unintentional drug overdose; gastric erosion; initiated use for headaches 12–24 Treated with buprenorphine

Admitted following overdose; hypokalaemia (potassium 2.2 mmol/L); initiated use for back 48 7-day inpatient admission

pain

Detoxification; nausea, vomiting and insomnia 72 Treated with buprenorphine–naloxone

Referred by mental health team for withdrawal from codeine–ibuprofen; peripheral 24–48 Treated with buprenorphine–naloxone

oedema; initiated use for dental pain

Withdrawal from Nurofen Plus; mild anaemia, gastric erosions; initiated use for headaches 50–70 Withdrawal managed with

and escalated dose buprenorphine

Referred for opioid pharmacotherapy; reported injecting oxycodone and taking zolpidem; 20–50 Referred for treatment of opioid

previous GI haemorrhage; initiated use for chronic back pain and escalated dose dependence

Detoxification; previous peptic ulcer; initiated use for headache and escalated dose 72–75 Stabilised on buprenorphine–naloxone

Mainly opioid-dependence or overdose

Detoxification; opioid-dependent; initiated use for dental pain 10–20 Withdrawal managed with

buprenorphine

Opioid withdrawal 40–50 Treated with buprenorphine

Codeine dependence; assessment for withdrawal treatment 12 LTFU

Pharmacotherapy for opioid dependence; initiated use for headaches 12–24 Treated with methadone

Opioid withdrawal 50 LTFU

Management of codeine dependence; initiated use for stress fracture pain 48–72 Treated with buprenorphine–naloxone

Codeine dependence; referred by mental health services; initiated use for back pain 12–24 Transferred to codeine phosphate

tablets

Treatment for opioid dependence; initiated use for back pain and escalated dose 24–48 Treated with buprenorphine–naloxone

Detoxification; initiated use for headache and escalated dose 20–24 Stabilised on buprenorphine–naloxone

OTC = over-the-counter. GI = gastrointestinal. LTFU = lost to follow-up. Hb = haemoglobin. AOD = alcohol and other drugs. ED = emergency department.

ICU = intensive care unit. ◆

use of high doses of NSAIDs such as years (Box 1). In the 15 cases where the OTC phate and 6800–9400 mg of ibuprofen. Most

ibuprofen. Four patients were admitted to a codeine–ibuprofen source was documented, patients did not document a brand of OTC

hospital intensive care unit, and 12 had the patient reported using multiple pharma- codeine–ibuprofen. Nurofen Plus was the

documented anaemia. cies to acquire these medications. brand specified by all nine patients who

However, 26 of the 27 patients reported A mean dose range of 34–47 tablets per reported the brand.

prolonged use (longer than 6 months) of day was reported in this case series. This A significant proportion of patients (n = 15)

supratherapeutic doses of OTC codeine–ibu- number of tablets would provide a mean reported initiating use of OTC codeine–ibu-

profen, with a mean duration of use of 3.6 daily dose of 435–602 mg of codeine phos- profen products for painful conditions,

MJA • Volume 193 Number 5 • 6 September 2010 295

M E D I C I N E A N D TH E C O M MU N I TY

including back pain and headaches, and sub- (more than 24 tablets). Due to concerns REFERENCES

sequently escalating the dose (Box 2). about harm from misuse of these prepara- 1 Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, et al. College on

Most patients (n = 16) were treated with Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on pre-

tions, rescheduling on 1 May 2010 requires scription opioid non-medical use and abuse: position

some form of opioid pharmacotherapy, with that all OTC codeine–ibuprofen products be statement. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 69: 215-232.

three patients undertaking buprenorphine- supplied directly by a pharmacist. 2 Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in

opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: con-

assisted detoxification, and 13 were started on In many of these cases, serious morbidity cerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;

opioid substitution treatment (OST). Of those resulted from use initiated for therapeutic 81: 103-107.

who received OST, most (n = 10) received 3 Lipman AG, Jackson KC; National Center on

reasons, such as persisting pain. Given that Addiction and Substance Abuse. Controlled pre-

sublingual buprenorphine–naloxone, and these drugs are likely to remain available scription drug abuse at epidemic level. J Pain

three received methadone solution. without prescription in Australia, physicians Palliat Care Pharmacother 2006; 20: 61-64.

4 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

should ask specifically about non-prescribed Administration. Results from the 2006 national

DISCUSSION analgesics when taking a medication history, survey on drug use and health: national findings.

and pharmacy personnel should consider the Rockville, Md: Office of Applied Studies, Depart-

To our knowledge, this is the largest collection ment of Health and Human Services, 2007.

of cases examining the complications of pro- risk of misuse when supplying these combi- (NSDUH Series H-32, DHHS Publication No. SMA

nation analgesic products. We believe the 07-4293.) http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/

longed use of supratherapeutic doses of OTC 2k6nsduh/2k6results.pdf (accessed Aug 2010).

codeine–ibuprofen. As with the published response of health professionals to opioid 5 Fischer B, Rehm J, Patra J, Cruz MF. Changes in

case studies on OTC analgesic misuse, we dependence from OTC codeine–ibuprofen illicit opioid use across Canada. CMAJ 2006; 175:

misuse is an important area for future 1385-1387.

found serious morbidities consistent with 6 Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths

NSAID toxicity20 including gastrointestinal research. from opioid analgesics in the United States. Phar-

disease, renal failure, anaemia and severe macoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006; 15: 618-627.

7 Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of

hypokalaemia.8,9 Many of our study’s patients ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical over-

differ from previously described opioid-using We thank the Victorian Addiction Inter-hospital dose fatalities. JAMA 2008; 300: 2613-2620.

treatment populations,21 with most reporting Liaison Association (VAILA) for their assistance.

8 Chetty R, Baoku Y, Mildner R, et al. Severe hypoka-

laemia and weakness due to Nurofen misuse. Ann

no drug and alcohol treatment history, and Clin Biochem 2003; 40: 422-423.

around half having no history of other current COMPETING INTERESTS 9 Dyer BT, Martin JL, Mitchell JL, et al. Hypokalae-

or past illicit substance use. Despite this, more mia in ibuprofen and codeine phosphate abuse.

Matthew Frei has received financial support from Int J Clin Prac 2004; 58: 1061-1062.

than half the patients described in this series Reckitt Benckiser (manufacturers of Suboxone and 10 Lambert AP, Close C. Life-threatening hypokalae-

received OST for opioid dependence. Nurofen Plus) to attend a conference. Suzanne mia from abuse of Nurofen Plus. J R Soc Med

2005; 98: 21.

As a case series relying on clinical data Nielsen has worked on a project (unrelated to this

11 Ford C, Good B. Over the counter drugs can be

opportunistically collected by specialist hospi- study) funded by Reckitt Benckiser and administered

highly addictive. BMJ 2007; 334: 917-918.

through Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre, and 12 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2007

tal addiction medicine services, this study has

Reckitt Benckiser has funded her attendance at a National Drug Strategy Household Survey: first

limitations. Our study is not able to estimate meeting unrelated to this work. Claire Tobin partici- results. Canberra: AIHW, 2008. (AIHW Cat. No.

the prevalence of codeine–ibuprofen misuse pated in the Victorian Public Health Training PHE 98.) http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/

or associated morbidity. While our case series Scheme, funded by the Victorian Department of phe/ndshs07-fr/ndshs07-fr-no-questionnaire.pdf

Health, while this study took place. (accessed Aug 2010).

suggests an association between chronic use 13 Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: AMH,

of supratherapeutic doses of OTC codeine– 2010: 495.

ibuprofen and medical complications, we AUTHOR DETAILS 14 Sproule BAP, Busto UEP, Somer GM, et al. Charac-

teristics of dependent and nondependent regular

have not looked at toxicity associated with Matthew Y Frei, MB BS, FAChAM, Head of users of codeine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999;

therapeutic doses. It is unclear whether these Clinical Services,1,2 and Adjunct Senior Lecturer3 19: 367-372.

cases represent a small proportion or a senti- Suzanne Nielsen, BPharm, PhD, MPS, Senior 15 Parfitt K, editor. Martindale: complete drug refer-

ence, 32nd edition. London: Pharmaceutical Press,

nel group of OTC codeine–ibuprofen misus- Research Fellow, Senior Pharmacist,1 and Adjunct 1999: 26.

ers in the Australian community. Despite Senior Lecturer4 16 Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, et al. Acetami-

these limitations, this study is consistent with, Malcolm D H Dobbin, PhD, MB BS, FAFPHM, nophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a

Senior Medical Adviser (Alcohol and Drugs)5 United States multicenter, prospective study.

and broader than, previously published Hepatology 2005; 42: 1364-1372.

reports.8,9,20 Claire L Tobin, RN, MPH, PhD (Public Health) 17 Hawkey CJ. NSAID toxicity: where are we and how

Candidate6 do we go forward? J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 650-652.

Information about morbidity resulting from

1 Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre, Eastern 18 Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointes-

misuse of OTC medications is scant, as com- tinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory

Health, Melbourne, VIC.

prehensive surveillance of adverse events drugs. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1888-1899.

2 South East Alcohol and Drug Service, Southern 19 Singh G. Gastrointestinal complications of pre-

associated with OTC medications relies on

Health, Melbourne, VIC. scription and over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-

patient reporting and health professional doc- inflammatory drugs: a view from the ARAMIS

3 School of Psychology and Psychiatry, Monash

umentation and submission of the event. University, Melbourne, VIC.

database. Am J Ther 2000; 7: 115-121.

Amounts of OTC medications purchased by 20 Dutch MJ. Nurofen Plus misuse: an emerging

4 Eastern Health Clinical School, Monash cause of perforated gastric ulcer. Med J Aust 2008;

individuals (eg, through “pharmacy shop- University, Melbourne, VIC. 188: 56-57.

ping”) are also difficult to monitor in the 5 Mental Health, Drugs and Regions Division,

21 Ross J, Teesson M, Darke S, et al. The characteris-

tics of heroin users entering treatment: findings

absence of a routine recording system, such as Victorian Department of Health, Melbourne, from the Australian treatment outcome study

that used to limit sale of pseudoephedrine, VIC. (ATOS). Drug Alcohol Rev 2005; 24: 411-418.

a methamphetamine precursor drug.22 At 6 School of Public Health and Preventive 22 Pharmacy Guild of Australia. Project Stop — Phar-

macy Guild initiative. Canberra: PGA, 2009. http://

time of writing, pharmacists were only Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC. www.guild.org.au/uploadedfiles/National/Public/

required to supervise dispensing of large Correspondence: Fact_Sheets/project_STOP.pdf (accessed Aug 2010).

pack sizes of OTC codeine–ibuprofen matthew.frei@easternhealth.org.au (Received 14 Sep 2009, accepted 16 Mar 2010) ❏

296 MJA • Volume 193 Number 5 • 6 September 2010

Вам также может понравиться

- Well Integrity Management System: 3 Days Workshop, 14 - 16 Jan 2021 Summarized By: Hudan HidayatullohДокумент34 страницыWell Integrity Management System: 3 Days Workshop, 14 - 16 Jan 2021 Summarized By: Hudan HidayatullohIslamОценок пока нет

- The Paint Inspector'S Field Guide: Experienced AuthorДокумент2 страницыThe Paint Inspector'S Field Guide: Experienced AuthorIslamОценок пока нет

- The Paint Inspector'S Field Guide: Experienced AuthorДокумент2 страницыThe Paint Inspector'S Field Guide: Experienced AuthorIslamОценок пока нет

- Atef Ibrahim Khalifa: Mobile No.: +201144487386 Email: Atef - Ibrahim@science - Suez.edu - Eg ObjectiveДокумент2 страницыAtef Ibrahim Khalifa: Mobile No.: +201144487386 Email: Atef - Ibrahim@science - Suez.edu - Eg ObjectiveIslamОценок пока нет

- ZZДокумент6 страницZZIslamОценок пока нет

- KKLL KK Qowmj JDMSM DMF MДокумент3 страницыKKLL KK Qowmj JDMSM DMF MIslamОценок пока нет

- KKLQQ P LklkkzznmamkДокумент3 страницыKKLQQ P LklkkzznmamkIslamОценок пока нет

- GE Krautkramer USN58L BrochureДокумент2 страницыGE Krautkramer USN58L BrochureIslamОценок пока нет

- POURBAIX DIAGRAMS (AutoRecovered)Документ10 страницPOURBAIX DIAGRAMS (AutoRecovered)IslamОценок пока нет

- On Crack Stability in Some Fracture Tests+: Economic. F&R ResearckДокумент12 страницOn Crack Stability in Some Fracture Tests+: Economic. F&R ResearckIslamОценок пока нет

- Fracture MechanicsДокумент3 страницыFracture MechanicsIslam0% (1)

- Web Results: Google Search Page HeaderДокумент3 страницыWeb Results: Google Search Page HeaderIslamОценок пока нет

- Word List by HundredsДокумент6 страницWord List by HundredsIslamОценок пока нет

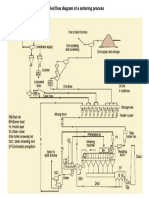

- Simplified Flow Diagram of A Sintering ProcessДокумент1 страницаSimplified Flow Diagram of A Sintering ProcessIslamОценок пока нет

- United States of AmericaДокумент5 страницUnited States of AmericaIslamОценок пока нет

- PDF SAH PDFДокумент4 страницыPDF SAH PDFIslamОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Derma OSCEДокумент3 страницыDerma OSCEUsama El BazОценок пока нет

- Question Paper 1 2018 PDFДокумент38 страницQuestion Paper 1 2018 PDFAyeshaОценок пока нет

- Epidemiology of Knee Injuries Among Boys and Girls in US High School AthleticsДокумент7 страницEpidemiology of Knee Injuries Among Boys and Girls in US High School AthleticsbomgorilaoОценок пока нет

- Treatment Guidelines For Hyponatremia Stay The.180Документ22 страницыTreatment Guidelines For Hyponatremia Stay The.180Carolyn CamposОценок пока нет

- ICU MSC Logbook-FinalДокумент101 страницаICU MSC Logbook-FinalCwali MohamedОценок пока нет

- ICE8112 Hazard of The Harad Wood (OCR) (T)Документ34 страницыICE8112 Hazard of The Harad Wood (OCR) (T)Percy PersimmonОценок пока нет

- Medical Prefixes and SuffixesДокумент7 страницMedical Prefixes and SuffixesGwyn Oona Florence ForroОценок пока нет

- M G University M.SC Applied Microbiology SyllabusДокумент52 страницыM G University M.SC Applied Microbiology SyllabusHermann AtangaОценок пока нет

- Final RM Mini ProjectДокумент33 страницыFinal RM Mini ProjectRahul ChaudharyОценок пока нет

- GE9 TheLifeAndWorksOfRizal CAMДокумент4 страницыGE9 TheLifeAndWorksOfRizal CAMCriselОценок пока нет

- Study Guide 1 Case Studies 1 and 2 Gutierrez, W.Документ3 страницыStudy Guide 1 Case Studies 1 and 2 Gutierrez, W.Winell Gutierrez100% (1)

- RESEARCHДокумент11 страницRESEARCHUzel AsuncionОценок пока нет

- Reagen Dan Instrumen Pendukung Untuk Laboratorium Pengujian COVID-19Документ14 страницReagen Dan Instrumen Pendukung Untuk Laboratorium Pengujian COVID-19Mike SihombingОценок пока нет

- For Printing EssayДокумент38 страницFor Printing EssayLito LlosalaОценок пока нет

- LDN Information PackДокумент17 страницLDN Information PackkindheartedОценок пока нет

- Nursing Diagnosis: Risk For Deficient Fluid Volume R/T Traumatic InjuryДокумент2 страницыNursing Diagnosis: Risk For Deficient Fluid Volume R/T Traumatic Injuryarreane yookОценок пока нет

- Discussion Question 1Документ3 страницыDiscussion Question 1Brian RelsonОценок пока нет

- Medical Terminology For Health Professions 7th Edition Ehrlich Test BankДокумент26 страницMedical Terminology For Health Professions 7th Edition Ehrlich Test BankGregorySimpsonmaos100% (46)

- 2016Документ45 страниц2016jimmyОценок пока нет

- Surgical Treatment For Mammary TumorsДокумент5 страницSurgical Treatment For Mammary Tumorsgrace joОценок пока нет

- CBSE Class 7 Science MCQs-Respiration in OrganismsДокумент2 страницыCBSE Class 7 Science MCQs-Respiration in Organismssiba padhy100% (3)

- Chapter Three: 3 .Materials and MethodsДокумент33 страницыChapter Three: 3 .Materials and MethodsGobena AdebaОценок пока нет

- Amiodarone Atrial Fibrillation BerberinДокумент10 страницAmiodarone Atrial Fibrillation Berberinharold jitschak bueno de mesquitaОценок пока нет

- Acute Asthma Paed WaniДокумент16 страницAcute Asthma Paed WaniNurul Syazwani RamliОценок пока нет

- Physiological Reports - 2022 - Mulder - Distinct Morphologies of Arterial Waveforms Reveal Preload Contractility andДокумент18 страницPhysiological Reports - 2022 - Mulder - Distinct Morphologies of Arterial Waveforms Reveal Preload Contractility andMASIEL AMELIA BARRANTES ARCEОценок пока нет

- Slide Jurnal Reading 2Документ20 страницSlide Jurnal Reading 2WulanSyafitriОценок пока нет

- Drug StudyДокумент4 страницыDrug StudySharwen_R_Rome_5572Оценок пока нет

- Pyle Et Al 1995 - Rapid Direct Count E ColiДокумент7 страницPyle Et Al 1995 - Rapid Direct Count E ColiFabio SenaОценок пока нет

- History of MicrobiologyДокумент5 страницHistory of MicrobiologyBernadine EliseОценок пока нет

- Ento 365 All Objective Qu.Документ30 страницEnto 365 All Objective Qu.Navneet KumarОценок пока нет