Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Unfair Labor Practices CASES

Загружено:

dayneblazeАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Unfair Labor Practices CASES

Загружено:

dayneblazeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Unfair Labor Practices In the meantime, the NCMB resumed conciliatory conferences between the

disputants. On 11 February 1994 respondent GREPALIFE submitted a draft

G.R. No. 126717 February 11, 1999 Agreement denominated by petitioner UNION as the "last and final offer by

GREAT PACIFIC EMPLOYEES UNION and RODEL P. DE LA ROSA, petitioners, Management," which proposed among others that —

vs. GREAT PACIFIC LIFE ASSURANCE CORPORATION, LABOR ARBITER

JOVENCIO LL. MAYOR JR. and NATIONAL LABOR COMMISSION (THIRD 4. Employee/members of the Union subject of dismissal notices shall be

DIVISION), respondents. reinstated under the same terms and conditions prior to their dismissal.

GREAT PACIFIC LIFE EMPLOYEES UNION and Great Pacific Life Assurance 5. The reinstatement of the employees mentioned in #4 shall be conditioned

Corporation entered sometime in 1990 into a Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) upon the submission by Alan B. Domingo and Rodel P. de la Rosa . . . . of their

to take effect 1 July 1990 until 30 June 1993. voluntary resignations to the Company upon the signing of this agreement.

On 18 May 1993, or about a month and a half before the expiration of the CBA, the 6. It is agreed and understood that Messrs. Domingo's and de la Rosa's

parties submitted their respective proposals and counter-proposals to serve as bases resignation while being effective thirty (30) days after submission, shall mean that

for their discussions on its projected renewal. The ensuing series of negotiations they need not report to the Company any longer. For the duration of the thirty

however resulted in a deadlock prompting petitioner Great Pacific Life Employees (30) day period, they shall be considered on leave with pay if they still have any

Union (UNION hereon) on 23 September 1993 to file a notice of strike with the outstanding vacation leave credits for 1993 and 1994.

National Conciliation and Mediation Board (NCMB) of the Department of Labor.

Despite several conciliatory conferences before the Board, the impasse could not be 7. Messrs. Domingo and de la Rosa, as showing of the Company's magnanimity,

resolved. Thus, on 3 November 1993 petitioner UNION led by its President Isidro shall be extended/given separation pay at the rate of one(1) month basic pay per

Alan B. Domingo and Vice President Rodel P. de la Rosa went on strike. year of service based on the new CBA

rates. 4

On 6 November 1993 respondent Great Pacific Life Assurance Corporation

(GREPALIFE hereon) required all striking employees to explain in writing within forty- On 14 February 1994 petitioner UNION in assenting to the offers expressed that —

eight (48) hours why no disciplinary action, including possible dismissal from

employment, should be taken against them for committing illegal acts against the

company in the course of the strike, particularly on 4 and 5 November. They were . . . . Management will make a full and immediate implementation of all the terms

warned that failure to submit their explanations within the prescribed period would be and conditions agreed upon.

construed as waiver of their right to be heard. The company directive was apparently

triggered by some violent incidents that took place while the strike was in progress. On its part, the Union shall forthwith lift the picket lines at the premises of the

Strikers reportedly blocked all points of ingress and egress of the company premises Company. All employees concerned shall terminate the strike and shall return to

in Makati City thus preventing GREPALIFE employees reporting for work from work promptly at the start of working hours on February 16, 1994.

entering their respective offices. These employees and third persons doing business

with the company, including lessees of the GREPALIFE building, were allegedly This acceptance should not be Interpreted to mean acquiescence by the Union to

forced by the strikers to submit their cars/vehicles, bags and other belongings to any portion of the aforementioned "last and final offer of Management" which

illegal search. 1 may be deemed to be contrary to law or public policy, the said offer being the

sole responsibility of Management. Furthermore, it is understood that should any

Complying with the order, UNION President Alan B. Domingo and some strikers portion of said offer be held invalid, the remainder of said offer which has been

explained that they did not violate any law as they were merely exercising their herein accepted shall not be affected thereby. 5

constitutional right to strike. Petitioner Rodel P. de la Rosa and the rest of the strikers

however ignored the management directive. On 15 February 1994 the UNION and GREPALIFE executed a Memorandum of

Agreement (MOA) before the NCMB which ended their dispute. The MOA provided in

GREPALIFE found the explanation of Domingo totally unsatisfactory and considered its Par 4 (on dismissals) that —

de la Rosa as having waived his right to be heard. Thus on 16 November 1993 both

UNION officers were notified of the termination of their services, effective (a) (Except for Domingo and de la Rosa) employees/members of the Union

immediately, as Senior Benefits Clerk and Senior Data Analyst, respectively. 2 All subject of dismissal notices on account of illegal acts committed in the course of

other strikers whose explanations were found unacceptable or who failed to submit the strike shall be given amnesty by the Company and he reinstated (under) the

written explanations were likewise dismissed. 3 Notwithstanding their dismissal from same terms and conditions prior to their dismissals following the signing of this

employment, Domingo and de la Rosa continued to lead the members of the striking agreement; (b) Messrs. Domingo and de la Rosa hereby reserve their right to

union in their concerted action against management.

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 1

question before the NLRC the validity or legality of their dismissal from strike in voked by GREPALIFE as basis for his dismissal was not adequately

employment . . . . 6 established. He also complains that he was later on forced to resign by management.

On 15 February 1994 Domingo and de la Rosa filed a joint letter of resignation with We hold that the NLRC did not commit grave abuse of discretion. The right to strike,

respondent company but emphasized therein that "(their) resignation is submitted while constitutionally recognized, is not without legal constrictions. 14 The Labor Code

only because the same is demanded by the Company, and it should not be is emphatic against the use of violence, coercion and intimidation during a strike and

understood as a waiver — as none is expressingly or impliedly made — of whatever to this end prohibits the obstruction of free passage to and from the employer's

rights (they) may have under existing contracts and labor and social legislation." 7 The premises for lawful purposes. The sanction provided in par. (a) of Art. 262 thereof is

MOA was subsequently incorporated in a new CBA which was signed on 4 March so severe that "any worker or union officer who knowingly participates in the

1994 but made effective on 1 July 1993 until 30 June 1996. commission of illegal acts during a strike may be declared to have lost his

employment status." 15

On 2 June 1994 Domingo and de la Rosa sue GREPALIFE for illegal dismissal, unfair

labor practice and damages. GREPALIFE submitted before the Labor Arbiter several affidavits of its employees

which de la Rosa did not refute. Of these documents, two (2) specifically described

The Labor Arbiter sustained the charge of illegal dismissal. He found that the the incidents that transpired during the strike on 4 and 5 November 1993. Security

evidence of respondent company consisting of affidavits of its employees was self- guard Rodrigo S. Butalid deposed —

serving and inadequate to prove the illegal acts allegedly committed during the strike

by Domingo and de la Rosa. Calling attention to the fifth. Paragraph Of the "last and (3) Since 3 November 1993, I have noticed that the striking employees have

final offer" Of respondent company, he rationalized that if indeed there was justifiable been doing the following: (a) the striking employees are picketing at the entrance

ground to terminate complaints' employment, there would have been no need for the and exit gates. (b) The striking employees would surround every vehicle

company to demand the resignation of the two union officers in exchange for the including vehicles of lessees of the Grepalife Building, that would enter the

reinstatement of all the strikers. He branded this "offer" as nothing more than a Grepalife premises, inspect the same and ask the driver of the vehicle to open

scheme to get rid the complainants, noting the undue haste with which their services the trunk of the vehicle so that the striking employees can see whether there are

were terminated by the respondent company. This, he observed, constituted nothing Grepalife business documents found therein. The vehicle which is being

less than a deprivation of due process of law. Thus, on 25 July 1995 the Labor Arbiter inspected cannot enter the Grepalife premises as the striking employees would

ordered respondent GREPALIFE to reinstate complaints to their former positions place a wooden bench in front of the vehicle. This wooden bench is only

without loss of seniority rights, with one (1) year back wages without qualification or removed to enable the vehicle to enter the Grepalife premises once the signal

deduction computed from 16 November 1993, the date of their dismissal. The other has been given by the striking employees, who stand at the sides and at the back

claims were dismissed for insufficiency of evidence. 8 of the vehicle, to the other striking employees who stand in front of the vehicle

that the vehicle has already been inspected and cleared. (c) If the striking

Both parties appealed to the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC). employees find Grepalife business documents in the vehicle being inspected, the

Respondent NLRC rejected the finding below that Domingo and de la Rosa. were striking employees would prevent the vehicle from entering the Grepalife

illegally dismissed, contending that a just cause for dismissal had been sufficiently premises. (d) The striking employees do not allow Grepalife, employees to enter

established. However, it agreed that respondent company failed to comply strictly with the Grepalife premises. Occasionally however, the striking employees will allow a

the requirements of due process prior to termination. In its decision dated 14 May Grepalife employees to enter the Grepalife office but on the condition that they

1996, it modified the ruling of the Labor Arbiter by directing respondent GREPALIFE will only get their personal belongings. (e) All persons who wish to enter the

to pay complainants their one (1) month salary 9 for non-observance of due process Grepalife premises are frisked and their bags/brief cases inspected. If a person is

prior to their dismissal. Considering that at the final negotiation for the settlement found to carry any Grepalife business document, he is not allowed to enter the

respondent company offered complainants separation pay of one (1) month salary for Grepalife premises. In the alternative, he would be allowed to enter but the

every year of service based on the new CBA rates in exchange for their voluntary Grepalife business document in his possession will be confiscated from him

resignation, the NLRC additionally ordered payment of such amount. 10 before he is allowed to enter.

On 19 June 1996 respondent GREPALIFE's motion for reconsideration was denied. 4. Among those who I have seen to have participated in the foregoing activities

Pending finality thereof, respondent company and Domingo entered into compromise are the following persons: (a) Alan B. Domingo who I know to be the President of

agreement11 which they submitted to the NLRC for approval. On 10 July 1996 the the Union; (b) Rodel P. dela Rosa who I know to be the Vice-President of the

NLRC considered the case against Domingo terminated, 12 and denied on 16 August Union;

1996 de la Rosa's motion for reconsideration. 13

The affidavit of another security guard, Wilson S. Concha was of similar import.

Pleading before us, petitioner de la Rosa raises two (2) issues. He asserts that he

was illegally dismissed because his actual participation in the illegal acts during the

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 2

Petitioner de la Rosa assails the inherent weakness of the sworn statements of these There should be no dispute that all the prohibited acts instituting unfair labor practice

security guards. But while it is true that affidavits may be regarded as infirm in essence relate to the workers' right to self-organization. Thus, an employer may be

evidence 16 before the regular courts unless the affiants are presented on the stand, held liable under this provision if his conduct affects in whatever manner the right of

such affidavits by themselves are acceptable in proceedings before the Labor Arbiter. an employee to self-organize. The decision of respondent GREPALIFE to consider

Under Sec. 7, Rule V, of the New Rules of Procedure of the NLRC, these the top officers of petitioner UNION as unfit for reinstatement is not essentially

proceedings, save for the constitutional requirements of due process, are not to be discriminatory and constitutive of an unlawful labor practice of employers under the

strictly governed by the technicalities of law and procedural rules. Section 3, par. 2, of above-cited provision. Discriminating in the context of the Code involves either

the same Rule provides that verified position papers are to be accompanied by all encouraging membership in any labor organization or is made on account of the

supporting documents including the affidavits of the parties' respective witnesses in employee's having given or being about to give testimony under the Labor Code.

lieu of direct testimony. It is therefore a clear mandate that the Labor Arbiter may These have not been proved in the case at bar.

employ all reasonable means to ascertain the facts of the controversy before him.

To elucidate further, there can be no discrimination where the employees concerned

Since de la Rosa did not present countervailing evidence, the NLRC correctly are not similarly situated. 19 A union officer has larger and heavier responsibilities

appreciated the affidavits of the two (2) security guards as having adequately than a union member. Union officers are duty bound to respect the law and to exhort

established the charges leveled against de la Rosa thus justifying his dismissal from and guide their members to do the same; their position mandates them to lead by

employment. example. By committing prohibited activities during the strike, de la Rosa as Vice

President of petitioner UNION demonstrated a high degree of imprudence and

We now turn to the claim of de la Rosa that he was forced to resign. It is true that the irresponsibility. Verily this justifies his dismissal from employment. Since the objective

draft Agreement submitted by respondent company before the NCMB expressly of the Labor Code is to ensure a stable but dynamic and just industrial peace, the

proposed that the reinstatement of its dismissed employees should be conditioned on dismissal of undesirable labor leaders should be upheld. 20

the voluntary resignations of Domingo and de la Rosa upon the signing of the

Agreements. It is also true that petitioner UNION was amenable to this proposition. It bears emphasis that the employer is free to regulate all aspects of employment

But the unalterable facts is that the MOA that was subsequently finalized and according to his own discretion and judgment. This prerogative flaws from the

executed did not carry this conditionally. Paragraph 4 (b) thereof merely expressed a established rule that labor laws do not authorize substitution of judgment of the

reservation by Domingo and de la Rosa of their right to question before the NLRC the employer in the conduct of his business. Recall of workers clearly falls within the

legality. of their dismissal from employment. Obviously they were referring to their ambit of management prerogative. 21 The employer can exercise this prerogative

dismissal on 16 November 1993 due to the illegal acts they allegedly committed in the without fear of liability so long as it is done in good faith for the advancement of his

course of the strike, and not to the voluntary resignation they were supposed to interest and not for the purpose of defeating or circumventing the rights of the

tender to management. employees under special laws or valid agreements. It is valid as long as it is not

performed in a malicious, harsh, oppressive, vindictive or wanton manner or out of

Significantly, the joint letter of resignation submitted by Domingo and de la Rosa a malice or spite.

day after the MOA was executed was never acted upon by respondent company. And

rightly so for, having been earlier dismissed (i.e., on 16 November 1993), these two That respondent company opted to reinstate all the strikers except Domingo and de la

(2) union officers had no more employment to resign from. To be sure, under the Rosa is an option taken in good faith for the just and lawful protection and

MOA their resignations were no longer a condition imposed by respondent company advancement of its interest. Readmitting the union members to the exclusion of

for the eventual reinstatement of the other strikers. This being the case, de la Rosa Domingo and de la Rosa was nothing less than a sound exercise of management

cannot now complain that he was forced to resign. Did he not explicitly acknowledge prerogative, an act of selt-preservation in fact, designed to insure the maintenance of

in his complaint with the Labor Arbiter that his cause of action was the Illegal peace and order in the company premises. 22 The dismissal of de la Rosa who had

termination of his services on 16 November 1993? 17 shown his capacity for unmitigated mischief was intended to avoid a recurrence of the

violence that attended the fateful strike in November.

Petitioner de la Rosa also claims that respondent company unreasonably singled out

the top officers of the UNION, including himself as unfit for reinstatement. Insisting WHEREFORE, the petition is DISMISSED. The decision of respondent National

that this act constitutes unfair labor practice, he demands entitlement to moral and Labor Relations Commission dated 14 May 1996 (a) finding that petitioner Rodel P.

exemplary damages. de la Rosa was legally dismissed, and, (b) ordering respondent Great Pacific Life

Assurance Corporation to pay petitioner his one (1) month salary or its failure to

We disagree. While an act or decision of an employer may be unfair, certainly not comply strictly with due process prior to the latter's termination and his one (1) month

every unfair act or decision constitutes unfair labor practice (ULP) as defined and salary per year of service based on the new CBA rates as separation pay, as well as

enumerated under Art. 248 Of the Labor Code. 18 its Resolution dated 16 August 1996 denying reconsideration, is AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 3

G.R. No. 123276 August 18, 1997 overtime expense it incurred during the said period, which averaged to P363,085.26

monthly. To streamline its operations, the president of RBS created a committee to

formulate guidelines on the availment of leaves and rendering of overtime work.

MARIO TIU and JONATHAN HAYUHAY, petitioners, vs. NATIONAL LABOR

RELATIONS COMMISSION and REPUBLIC BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC.

(CHANNEL 7), respondents. On 11 June 1991, RBS, through its personnel department, furnished GMAEU a copy

of the new guidelines and requested the latter to comment thereon. The union did not

file any comment. On 25 June 1991, RBS officially issued the implementing

This is a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court to annul and set

guidelines "on the availment of leaves and rendering of overtime services." The

aside the resolution of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) dated 28

following day, GMAEU sent a letter to the president of RBS wherein it argued that:

November 1994 in NCR Case No. 00-08-0453-91 which affirmed the decision of labor

arbiter Edgardo Madriaga dated 18 February 1994 holding the strike held by GMA

Channel 7 Employees Union (GMAEU) on 2 August 1991 as illegal and declaring the 1. The union was not consulted in the formulation of said guidelines which was a clear

fourteen (14) GMAEU union officers who knowingly participated in the illegal strike to violation under Sec. 3(c) of the collective bargaining agreement;

have lost their employment status.

2. The guidelines would render nugatory the collective bargaining agreement

The records show that of the Fourteen (14) GMAEU officers involved in the strike, ten provisions on the same subject;

(10) officers did not appeal the labor arbiter's decision and opted to avail of the

optional retirement benefits under the collective bargaining agreement with private 3. The diminution of benefits being enjoyed by all employees with respect to the mid-

respondent Republic Broadcasting System Inc. (RBS) The remaining four (4) union year bonuses (from 2-1/2 months to 1-1/2 months constitutes a withdrawal of an

officers, namely: Mario Tiu, Nani Hayuhay, Bong Cerezo and Virgilio Santoyo, existing company policy).

appealed to the NLRC.

Thereafter, RBS management and GMAEU officials met on 3 July 1991 and on 10

From the NLRC decision, Virgilio Santoyo filed a separate petition for certiorari before July 1991 to thresh out the issues raised by GMAEU in its 26 June 1991 letter. Both

this Court, docketed as G.R. No. 122613. In a resolution dated 31 January 1996, the talks, however, were short lived as the union refused to hold further talks with RBS.

Court dismissed Santoyo's petition "for failure to sufficiently show that the respondent

Commission (NLRC) had committed a grave abuse of discretion in rendering the

On 12 July 1991, GMAEU filed a Notice of Strike with the National Conciliation and

questioned judgment."

Mediation Board (NCMB) based on unfair labor practices allegedly committed by

RBS, as follows:

Considering that Santoyo and herein petitioners were dismissed under the same

factual circumstance, the Court reviewed the records of G.R. No 122613 to determine

1. Gross violation of the existing collective bargaining agreement;

whether the ruling laid therein applies in the case at bar. The Court notes that the

issues raised by Santoyo in his petition were procedural in character Santoyo alleged

that he was never represented by counsel in the proceedings both before the labor 2. Employees (members and officers) coercion;

arbiter and the NLRC and was denied the opportunity to present his evidence. This

allegation, however, had no factual basis as the records showed that he was 3. Union interference; and

represented by counsel during the entire proceedings below. In contrast, the present

petition raised substantive issues concerning the legality or illegality of the strike

conducted by GMAEU on 2 August 1991. 4. Discrimination.

The Court required both public and private respondents to file their comment on the The NCMB set a conciliation meeting on 19 July 1991, but as early as 16 July 1991

petition. Private respondent RBS filed its comment on 23 April 1996 and public the Union held a strike vote among its members and submitted the results thereof to

respondent NLRC filed its own comment on 9 December 1996. Petitioners filed a the NCMB on 18 July 1991 which showed that majority of the union members voted

reply to both comments on 4 March 1997. Since the parties have exhaustively argued to go on strike.

their position in their respective pleadings, the Court dispensed with the filing of

memoranda and considered this case submitted for resolution. During the conciliation meeting held on 19 July 1991, RBS, through counsel, informed

GMAEU's officers that RBS did not violate any provision in the collective bargaining

The material and relevant facts are as follows: agreement since the issuance of the guidelines was a management prerogative duly

recognized in their agreement. As regards GMAEU's charges of coercion, union

interference and discrimination, RBS argued that these alleged unfair labor practices

RBS had a collective bargaining agreement with GMAEU which took effect on 2 July were neither raised by the union in its 26 June 1991 letter nor during their 3 July and

1989. After the first quarter of 1991, RBS management noted the huge amount of

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 4

10 July 1991 talks. RBS' counsel requested GMAEU's officers to name the persons or d. The union violated the no strike-no lockout clause of the CBA with RES; thus

officers of RBS involved in the alleged unfair labor practices and to state the specific rendering the strike held on 2 August 1991 illegal. As aforementioned, the NLRC

act or acts complained of so that RBS management could adequately refute said affirmed the labor arbiter's decision in a resolution dated 28 November 1994.

allegations or impose appropriate disciplinary actions against its erring officers.

GMAEU's officers, however, ignored both RBS' and the labor conciliator's requests for In their petition, petitioner raised six (6) alleged NLRC errors which ultimately narrow

a bill of particulars. down to one issue —

In a second conciliation meeting held on 25 July 1991, RBS reiterated its request to WHETHER OR NOT THE NLRC COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION

GMAEU's officers to furnish RBS the details of the alleged unfair labor practices WHEN IT UPHELD THE LABOR ARBITER'S DECISION THAT PETITIONERS

committed by RBS' officers. Again, the Union denied RBS' request and refused to STAGED AN ILLEGAL STRIKE ON 2 AUGUST 1991.

hold any further talks with RBS management. On the same day, RBS filed a motion to

dismiss GMAEU's notice of strike and forewarned the Union about the consequences

of an illegal strike. Petitioners argue that any defect in their pro-forma notice of strike was cured when

the NCMB took cognizance of the case and conducted conciliation proceedings on 19

July and 25 July 1991. In addition, upon assumption by the Secretary of Labor of

On 2 August 1991, the union struck. On the same day, RBS filed a complaint for jurisdiction over the dispute and certification of the same for compulsory arbitration, it

illegal strike and unfair labor practice against GMAEU and its fourteen (14) officers is presumed that the union had complied with the procedural requirements under the

(hereafter, illegal strike case). The case was docketed as NLRC Case 00-08-04531- labor code for a valid notice of strike.

91. Meanwhile, the Secretary of Labor immediately assumed jurisdiction over the

case, issued a return-to-work order, and certified the case to the NLRC for

compulsory arbitration (hereafter, certified case). The case was docketed as NCMB- Anent the alleged unfair labor practice committed by RBS, petitioners assert that this

NCR-050-7-488-91. issue was thoroughly discussed with sufficient particularity in their position papers

filed in the certified case and in the illegal strike case; hence. "their notice of strike

was sufficient in form and in substance."

In the certified case, the labor arbiter found no factual and legal ground to hold RBS

guilty of unfair labor practices against the Union. On appeal (docketed as NLRC-NCR

CC No. 00076-01), the NLRC affirmed the labor arbiter's decision in a resolution Petitioners further argue that they believed in good faith that RBS had committed acts

dated 31 July 1992. of unfair labor practice which induced them to proceed with the strike on 2 August

1991. Since it was an unfair labor practice strike, the no-strike clause in the collective

bargaining agreement with RBS does not apply They also showed good faith by their

Meanwhile, the labor arbiter continued to hear the illegal strike case filed by RBS immediate compliance with the return-to-work order issued by the Secretary of Labor

against GMAEU. On 18 February 1994, the labor arbiter rendered judgment declaring upon assuming jurisdiction over the case.

the strike illegal and the union officers who knowingly participated in the illegal strike

to have validly lost their employment status based on the following reasons:

Private respondent RBS refutes these arguments and asserts that the factual findings

of the labor arbiter and the NLRC, being supported by substantial evidence, should

a. "The notice of strike did not specifically charge the company (RBS) of unfair labor be upheld by this Court. This means that petitioners cannot invoke the protective

practices, only pro formaallegations of gross violation of the collective bargaining mantle of the good faith strike doctrine because the alleged issues in the notice of

agreement, employees coercion, union interference, and discrimination." It is strike were never substantiated by the union either before or during the conciliation

"defective as it consisted of vague and general charges which could not be proceedings. The union violated the no strike clause under the collective bargaining

substantiated and which the company could not properly defend itself against." agreement and should be held accountable for their acts by considering them validly

dismissed from their employment with RBS.

b. "The absence of evidence on record that the mandatory cooling-off period and

strike vote under the law were complied which renders the strike staged by the We find no merit in the petition at bar.

respondents illegal per se on technical grounds."

The notice of strike filed by the union before the NCMB on 12 July 1991 contained

c. "On the merits . . . there are no strikeable grounds as there was no bargaining general allegations that RBS management committed unfair labor practices by its

deadlock between the parties. The alleged gross violation of the collective bargaining gross violation of the economic provisions in their collective bargaining agreement

agreement cannot constitute an unfair labor practice because said charges were and by alleged acts of coercion, union interference and discrimination which

bereft of factual and legal basis." "There being no unfair labor practice, it follows that amounted to union busting. It is the union, therefore, who had the burden of proof to

there is no strikeable issue to support the strike conducted by herein respondents (the present substantial evidence to support these allegations.

Union)."

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 5

It is not disputed that prior to 12 July 1991, the union treated RBS' issuance of the The Court affirms the factual finding of the labor arbiter and the NLRC that" there was

"guidelines on the availment of leaves and rendering of overtime services" as "gross" no strikeable issue to support respondent's (the Union) subject strike." The evidence

violations of the existing collective bargaining agreement. In its talks with the union, show that the union anchored its position on alleged unfair labor practices in order to

RBS painstakingly explained that the said allegation was unfounded because the evade not only the grievance machinery but also the no strike clause in their

issuance of said guidelines was RBS' management prerogative. Up to that point, the collective bargaining agreement with RBS.

union never raised the issue of unfair labor practices allegedly committed by RBS'

officials under Article 248 of the Labor Code. But in its notice of strike filed two days RBS did not issue its implementing guidelines dated 24 June 1991 concerning the

later, the union raised issues of coercion, discrimination, and union interference for availment of leaves and rendering of overtime services in an arbitrary manner. The

the first time. union was promptly informed that RBS' decision was based on its management

prerogative to regulate all aspects of employment, subject of course to well-defined

Significantly, the union had two (2) conciliatory meetings arranged by the limitations imposed by law or by contract.

NCMB at which it could have substantiated these additional allegations. However, the

fact that it had submitted the results of the strike vote even ahead of the conciliatory Even assuming arguendo that in the issuance of said guidelines RBS may have

meetings, and continuously refused to substantiate its allegations in its notice of strike violated some provisions in the collective bargaining agreement, there was no

thereafter, lends credence to the NLRC's observation that these charges were palpable showing that the same was a flagrant and/or malicious refusal to comply

indiscriminately hurled against RBS to give a semblance of validity to its notice of with its economic provisions. (Book V Implementing Rules of the Labor Code, Rule

strike. XIII, Section 1) Hence, the law mandates that said violation "shall not be considered

unfair labor practice and shall not be strikeable."

Under Rule XIII Sec. 4 Book V of the Implementing Rules of the Labor Code —

The bottom line is that the union should have immediately resorted to the grievance

. . . . . In cases of unfair labor practices, the notice of strike shall as far as machinery established in their agreement with RBS. In disregarding said procedure

practicable, state the acts complained of and the efforts to resolve the dispute the union leaders who knowingly participated in the illegal strike "have acted

amicably. unreasonably, and, as such, the law cannot interpose its hand to protect them from

the consequences of their behavior" (National labor Union v. Philippine Match

Upon the other hand, Rule III Sec. 6 provides that — Factory, 70 Phil. 300; United Seamen's Union v. Davao Shipowner's Association, 20

SCRA 1226)

xxx xxx xxx

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the petition is hereby DISMISSED, there being

no substantial evidence of grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of

During the (conciliation) proceeding, the parties shall not do any act which may jurisdiction on the part of the NLRC.

disrupt or impede the early settlement of the dispute. They are obliged, as part of

their duty to bargain collectively in good faith, to participate fully and promptly in

the conciliation meetings called by the regional branch of the board. . . . . SO ORDERED.

(emphasis supplied)

Petitioners plead that their contemporaneous acts, reckoned from their 26 June 1991

letter to RBS up to the actual strike held on 2 August 1991, were justified based on its

honest belief that RBS was committing unfair labor practices. Stated otherwise, "the

presumption of legality (of the strike) prevails even if the allegations of unfair labor

practices are subsequently found out to be untrue." (citing Muster Iron Labor Union v.

NLRC, 219 SCRA 47)

The Court is not unmindful of this rule, but in the case at bar the facts and the

evidence did not establish even at least a rational basis why the union would wield a

strike based on alleged unfair labor practices it did not even bother to substantiate

during the conciliation proceedings. It is not enough that the union believed that the

employer committed acts of unfair labor practice when the circumstances clearly

negate even a prima facie showing to warrant such a belief.

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 6

Specific ULP Acts of Employer attend the hearing of the petition for certification election. The management

refused to acknowledge receipt of said notice (Annex "E," Case 486-80).

Interference

6. On February 28, 1980, private respondent preventively suspended the union

G.R. No. L-67158, 67159, 67160, 67161, & 67162 May 30, 1988 officers and members who attended the hearing namely: Cornelio Pangilinan,

president; Leo Tropics, vice- president; Olimpio Gumin, treasurer; Buenaventura

CLLC E.G. GOCHANGCO WORKERS UNION, CORNELIO L. PANGILINAN, LEO Puno, director; Reynaldo Dayrit, sgt-at-arms; Ernesto Ramirez; Ernesto Galang;

TROPACIO, OLIMPIO GUMIN, JUANITO SUBA, ROLANDO SANTOS, RUBEN Odilon Lising; Jesus Daquigan; and Edilberto Quiambao. The common ground

BUELA, ODILON LISING, REYNALDO DAYRIT, ROGELIO MANGUERRA, alleged by private respondent for its action was "abandonment of work on

ORLANDO NACU, DIOSILINO PERDON, ERNESTO GALANG, ORLANDO February 27, 1980." On the same date, all the gate passes of all the above-

PANGILINAN, JESUS SEMBRANO, RENATO CASTANEDA, EDILBERTO mentioned employees to Clark Air Base were confiscated by a Base guard.

BINGCANG, ERNESTO CAPIO, RUFO A. BUGAYONG, RICARDO S. DOMINGO,

TERESITO CULLARIN, ISRAEL VINO, ERNESTO RAMIREZ, ROMEO S. GINA, 7. Claiming that private respondent instigated the confiscation of their gate

ARNEL CALILUNG, PEDRO A. SANTOS, RODOLFO CAPITLY, BUENAVENTURA passes to prevent them from performing their duties and that respondent firm did

B. PUNO, EDILBERTO QUIAMBAO, FERNANDO LISING, ERNESTO M. TUAZON, not pay them their overtime pay, 13th month pay and other benefits, petitioner

MARCELO LANGUNSAD, MARCELINO VALERIO, SERAFIN PAWA, JESUS S. union and its members filed a complaint for constructive lockout and unfair labor

DAQUIGAN, and ISMAEL CAYANAN, petitioners, vs. NATIONAL LABOR practice against private respondent, docketed as R03-AB Case No. 486-80 on

RELATIONS COMMISSION (NLRC), and e.g. GOCHANGCO, INC., respondents. March 10, 1980.

The cases before the Court pit labor against management, in which, on not a few 8. On March 12, 1980, private respondent filed an application for clearance to

occasions, it is labor that has cause for complaint. dismiss Cornelio Pangilinan, Leo Tropics, Olimpio Gumin, Reynaldo Dayrit,

Odilon Lising, Edilberto Quiambao; Ernesto Ramirez, Ernesto Galang,

The Solicitor General states the facts as follows: Buenaventura Puno, Arnel Calilung, Romeo Guina, docketed as R03-AB Case

No. 556-80. Subsequently private respondent filed another clearance to dismiss

Jesus Daquigan, Serafin Pawa and Rufo Bugayong, docketed as R03-A-B Case

xxx xxx xxx No. 55780.

1. Petitioner union is a local chapter of the Central Luzon Labor Congress 9. On April 22,1980, petitioner Ricardo Dormingo who was preventively

(CLLC), a legitimate labor federation duly registered with the Ministry of Labor suspended on April 17, 1980 filed a complaint for unfair labor practice against the

and Employment (MOLE), while the individual petitioners are former employees latter, docketed as R03-AB Case No. 55880.

of private respondent who were officers and members of the petitioner union.

10. On April 30, 1980, the services of nine (9) more union members, namely:

2. Private respondent is a corporation engaged in packing and crating, general Ernesto Tuason, Israel Vino, Pedro Santos, Juanita Suba, Edilberto Sarmiento,

hauling, warehousing, sea van and freight forwarding, Diosalino Pandan, Antonio Razon, Benjamin Capiz and Jesus Sembrano, were

terminated by private respondent on the ground that its contract with the U.S. Air

3. Sometime in January 1980, the majority of the rank and file employees of Force had expired. The rune employees filed a complaint for illegal dismissal

respondent firm organized the e.g. Gochangco Workers Union as an affiliate of against private respondents on June 2, 1980. docketed as R03-AB Case No.

the CLLC. On January 23, 1980, the union filed a petition for certification election 663-80.

under R03-LRD (MA) Case No. 178-80. The MOLE Region 111 office set the

hearing for the petition on February 27,1980. 11. On May 9, 1980, private respondent filed with MOLE, Region III, a Notice of

Termination of Contract together with a list of employees affected by the

4. On February 7,1980, the CLLC national president wrote the general manager expiration of the contract, among them, the 39 individual petitioners herein.

of respondent firm informing him of the organization of the union and requesting

for a labor management conference to normalize employer-employee relations 12. All the aforementioned cases were consolidated and assigned to Labor

(Annex "D," Case 486-80). Arbiter Andres Palumbarit.

5. On February 26,1980, the, union sent a written notice to respondent firm 13. After heating, Labor Arbiter Federico S. Bernardo who took over the cases

requesting permission for certain member officers and members of the union to from Arbiter Palumbarit rendered a decision dated July 2, 1982, the dispositive

portion of which reads:

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 7

WHEREFORE, In view of all the foregoing, the instant complaint of complainants

is hereby granted and the respondent's application for clearance is hereby 18. Eduardo Alegado 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

denied.

19. Teresito Cullarin 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

The respondent is hereby ordered:

20. Rogelio Manguerra 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

1. To reinstate all the suspended/dismissed employees to their former 21. Ruben Buela 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

positions without loss of seniority rights and other privileges, with full

backwages including cost of emergency living allowance from the date of their 22. Rolando Santos 11,134 00 7,663.00 18,767.00

suspension/dismissal up to the supposed date of actual reinstatement, as

follows:

23. Ricardo Domingo 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

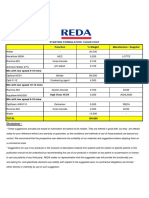

NAME BACK- WAGES ECOLA TOTAL 24. Serafin Pawa 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

1.Cornelio Pangilinan P 11,266.00 P 7,738.00 P 19,004.00 25. Rufo Bugayong 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

2. Leo Tropico 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 26. Ernesto Santos 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

3. Olimpio Gumin 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 27. Ismael Cayanan 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

4. Reynaldo Dayrit 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 28. Marcelo Lagansad 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

5. Buenaventura Puno 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 29. Marcelino Valerio 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00

6. Ernesto Galang 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 30. Ernesto M. Tuazon 10,618.00 7,225.00 18,767.00

7. Ernesto Ramirez 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 31. Israel Vino 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

8. Edilberto Quiambao 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 32. Pedro Santos 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

9 Jesus Daquigan 11,266.00 7,738.00 19,004.00 33. Juanita Suba 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

10. Renato Castaneda 11,134.00 7,633.00 19,004.00 34.Edilberto Sarmiento 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

11. Edilberto Bingcang 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00 35. Diosalino Pendon 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

12. Benedicto Capio 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00 36. Antonio Razon 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

13. Orlando Nacu 11,134.00 7,633.00 18,767.00 37. Benjamin Capiz 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

14. Rodolfo Capitly 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00 38. Jesus Sembrano 10,618.00 7,225.00 17,843.00

15. Arnel Calilung 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00 GRAND TOTAL P 419,636.00 P 706,973.00 P267,337.00

2. To restore transportation privilege as being extended before the filing of the

16. Romeo Gina 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00 instant case; and

17. Orlando Pangilinan 11,134.00 7,663.00 18,767.00 3. If their reinstatement is no longer possible due to closure of the

establishment, in addition to the payment of their full backwages and cost of

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 8

living allowance, to pay their respective separation pay as provided for under why we should hold otherwise as far as labor cases are concerned. Accordingly, we

the Labor Code. yield to the respondent Commission's finding that the e.g. Gochangco, Inc. had filed

its appeal on time. It may be further noted that the petitioners themselves can offer no

14. Private respondent appealed to the NLRC which rendered the questioned proof, other than vague inferences from circumstances, of the belated appeal they

decision on May 31, 1983 as follows: allege.

WHEREFORE, in the light of foregoing premises, the appealed decision is This is not to say, however, that such an appeal has judgment. The Solicitor General

hereby set aside and another one issued dismissing the above-entitled cases himself urges that we grant that, petition and hence, reverse the respondent

filed by the complainants-appellees for lack of merit and granting the application Commission. But apart from such urgings, the records themselves show that a

for clearance to terminate the services of individual complainants-appellees filed reversal is in order.

by respondent-appellant.

We are convinced that the respondent company is indeed guilty of an unfair labor

15. Petitioners moved for a reconsideration of the above decision on July 12, practice. It is no coincidence that at the time said respondent issued its suspension

1983 which NLRC denied in a resolution dated December 6,1983. and termination orders, the petitioners were in the midst of a certification election

preliminary to a labor management conference, purportedly, "to normalize employer-

employee relations." 5 It was within the legal right of the petitioners to do so, 6 the

16. Hence, this petition. 1 exercise of which was their sole prerogative, 7 and in which management may not as

a rule interfere. 8 In this connection, the respondent company deserves our strongest

xxx xxx xxx condemnation for ignoring the petitioners' request for permission for some time out to

attend to the hearing of their petition before the med-arbiter. It is not only an act of

The petitioners assign three errors in support of their petition: arrogance, but a brazen interference as well with the employees right to self-

organization, contrary to the prohibition of the Labor Code against unfair labor

practices. 9

I. THAT PUBLIC RESPONDENT GRAVELY ABUSED ITS DISCRETION AND

SERIOUSLY COMMITTED ERRORS IN LAW IN CONSIDERING PRIVATE

RESPONDENTS EVIDENCE INTRODUCED FOR THE FIRST TIME ON APPEAL, But as if to add insult to injury, the company suspended the petitioners on the ground

AND PUBLIC RESPONDENT NLRC HAS SERIOUSLY COMMITTED ERRORS IN of "abandonment of work" 10on February 27, 1980, the date on which, apparently, the

GIVING DUE COURSE TO PRIVATE RESPONDENT APPEAL FROM THE pre-election conference had been scheduled. (The petitioners sought permission on

DECISION OF LABOR ARBITER FEDERICO S. BERNARDO, ALTHOUGH SAID February 26, 1980 while the suspension order was issued on February 28, 1980.)

APPEAL WAS NOT VALIDLY PERFECTED ON TIME; What unfolds here is a clear effort by management to punish the petitioners for their

union activities.

II. THAT PUBLIC RESPONDENT NLRC COMMITTED SERIOUS ERRORS IN LAW

IN RENDERING A DECISION THAT IS CONTRARY TO THE EVIDENCE ON As a consequence of such a suspension, the Clark Air Base guards confiscated the

RECORD(S); and employees' gate passes, and banned them from the base premises. We cannot be

befooled by the company's pretenses that "[t]he subsequent confiscation by the

Americans of the complainants' passes is beyond the powers of management." To

III. THAT PUBLIC RESPONDENT NLRC COMMITTED AN ERROR IN NOT start with, those passes would not have been confiscated had not management

AWARDING BACK WAGES TO THE INDIVIDUAL PETITIONERS FOR REFUSAL ordered the suspension. As put by the Solicitor General, "the U.S. Air Force

OF PRIVATE RESPONDENT TO REINSTATE THEM AFTER RENDERING OF THE authorities could not have known who were supposed to report for work on February

DECISION OF LABOR ARBITER FEDERICO S. BERNARDO AND AFTER SAID 27, 1980," 12and who were under suspension. Conversely, in the absence of such a

LABOR ARBITER ORDERED PRIVATE RESPONDENT TO REINSTATE THEM. 2 suspension order, there was no ground to seize such gate passes. Base guards, by

themselves, cannot bar legitimate employees without the 'proper sanction of such

On the first issue, the petitioners submit that the motion for reconsideration, treated employees'employers.

subsequently as an appeal, 3 of the private respondent had been filed beyond the ten-

day period prescribed by the Labor Code, in the absence of any statement thereon as What disturbs us even more, however, is the perplexing gullibility with which the

to material dates. The respondent Commission ruled that it was, on the strength of respondent National Labor Relations Commission would fall for such an indefensible

receipts in possession of the Labor Department disclosing such dates and showing position. Said the Commission: "So, with their gate passes confiscated, even if

that said appeal had been seasonably filed. As a matter of practice, and in connection management will reinstate them, without the gate passes, they cannot enter the US

with ordinary civil cases, this Court has assumed a stance of liberality towards the Clark Airforce Base and perform their jobs, for the gate pass is a pre-requisite for their

application of the material data rule, if it in be otherwise verified from other evidence entrance for employment." 13 For surely, and as we stated, the petitioners were

that the appeal had been perfected within the time prescribed. 4 We see no reason dispossessed of those gate passes precisely because of the suspension meted out

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 9

against them. It is not the other way around, as the Commission would have us

behave, for the confiscation of such passes would not furnish a ground for 15. Renato Castaneda May 1976 Packer

suspension. Reinstatement then would have deprived the base gullibility guards any

right to hold on to such passes any further. In the absence of superior orders, mere 16. Edilberto Sarmiento Aug. 1977 Packer

base guards are bereft of any discretion to act on such matters.

17, Eduardo Alegado Dec. 1977 Packer

In finding the petitioners' suspension illegal, with more reason do we hold their

subsequent dismissal to be illegal. We are not persuaded by the respondent firm's 18. Benjamin Capiz June l978 Packer

argument that final termination should be effected as the contract has

expired." 14 What impresses us is the Solicitor General's submission that the 19. Antonio Razon Nov. 1978 Packer

petitioners were regular employees and as such, their tenure did not end with the

expiration of the contract. We quote: 20. Edilberto Bingcang May 1978 Packer

The records show that petitioners were do so, 6 The ar employees whose 21. Ernesto Santos June 1978 Packer

employment did not terminate with the expiration of private respondent's contract

with the U.S. Air Force. In their position paper in the arbitration proceedings, they 22. Benedicto Capio Oct. 1978 Packer

averred that been employer employed by private respondent for six (6) months or

more before they were terminated as follows: 23. Rufo Bugayong May 1977 Packer

24. Ricardo S. Domingo Dec. 1978 Packer

NAMES DATE EMPLOYED POSITION

25. Teresito Cullarin Mar. 1978 Packer

1. Cornelio Pangilinan Jan. 1976 Driver

26. Israel Vino May 1979 Packer

2. Leo Tropico Mar. 1977 Driver

27. Ernesto Ramirez Mar. 1979 Packer

3. Olimpio Gumin Jan. 1977 Driver

28. Romeo S. Gina Sept. 1979 Packer

4. Juanita Suba June l976 Driver

29. Arnel Calflung Sept. 1979 Packer

5. Rolando Santos Oct. 1978 Driver

30. Pedro A. Santos May 1979 Packer

6. Ruben Buela Jan. 1975 Packer

31. Rodolfo Capitly Nov. 1978 Packer

7. Odilon Lising May 1975 Packer

32. Buenaventura B. Puno Sept. 1979 Packer

8. Reynaldo Dayrit May 1976 Packer

33. Edilberto Quiambao Nov. 1978 Packer

9. Rogelio Manguerra Mar. 1977 Packer

34. Fernando Lising Jan. 1975 Checker

10. Orlando Nacu May 1977 Packer

35. Ernesto M. Tuazon Feb. 1975 Mechanic

11. Diosalino Perdon May 1977 Packer

36. Marcelo Lagansad Jan. 1963 Mechanic

12. Ernesto Galang June 1977 Packer

37. Marcelino Valerio May 1979 Mechanic

13. Orlando Pangilinan June l977 Packer

38. Serafin Pawa Feb. 1979 Packer

14. Jesus Sembrano May 1977 Packer

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 10

alleged president of complainant-appellee union Benigno Navarro, Sr., contends

39. Jesus S. Daquigan May 1977 Packer that Id Atty. Solomon has no authority to appear floor and in behalf of individual

complainants-appellees who waived their rights and interests in these cases

40. Ismael Cayanan May 1978 Packer 15 since there was no authority from him. Records, however, disclose that said Atty.

Solomon had been the attorney of record for complainants-appellees since the

inception of these cases, and, therefore, is authority to represent them cannot be

As regular employees, the petitioners' tenure are secure, and their dismissal must be questioned- not even by Ministry. Navarro who allegedly took over the

premised on a just cause. 16 presidency of complainant-appellee union after the disappearance of the former

president, Mr. Ficardo Alconga, Sr. And besides, the waiver of rights and

We find none here. What we find, instead, are flimsy attempts by the respondent interests were personally executed by the signatories therein and all that Atty.

company to discredit the person of the petitioners' counsel, or their officers, and other Solomon did was to assist them. 21

resorts to argumenta ad hominem. 17

xxx xxx xxx

There is no merit in the claim that the petitioners' terms were coterminous with the

duration of the contract. There is nothing in the records that would show that the We find this puzzling for clearly, Labor Arbiter Aquino's resolution refers to other

petitioners were parties to that contract. It appears furthermore that the cases22 and not the instant unfair labor practice controversy. The Commission cannot

petitioners 18 were in the employ of the respondent company long before that contract feign simple mistake for such a lapse. Wittingly or unwittingly, it had made itself a

was concluded. They were not contract workers whose work terms are tied to the Dawn of the respondent corporation or otherwise had yielded to its influence. The

agreement, but were, rather, regular employees of their employer who entered into Court rebukes Atty. Isagani M. Jungco counsel for the respondent company, for his

that contract. unbecoming act and the individual members of the Commission itself, for besmirching

the integrity of the Commission.

But even if dismissal were warranted, the same nonetheless faces our disapproval in

the absence of a proper clearance then required under the Labor Code. 19 It is true In any event, we have held that unfair labor practice cases are not, in view of the

that efforts were undertaken to seek such a clearance, yet there is no showing that it public interest involved, subject to compromises. 23 Furthermore, these alleged

was issued. That still taints the dismissal with the vice of illegality. waivers do not appear to have been presented in the first instance. They cannot be

introduced for the first time on appeal.

The Court likewise rejects the claims of an alleged waiver by the petitioners of their

economic demands, in the light of an alleged order issued by Labor Arbiter Luciano We come, finally, to the respondent company's liability for backwages and for

Aquino in connection with another case(s) involving the same parties. (It was Labor emergency cost of living allowances (ECOLA). In its appeal, the company denies any

Arbiter Federico Bernardo who penned the unfair labor practice/illegal dismissal liability, pointing to "[r]epresentative samples of the documents evidencing payment

case.) The Honorable Aquino's disposition reads: was likewise submitted due to the voluminous records which cannot be all

produced." 24 The Commission accepted this argument, noting that 'these xerox

The records show that a "Waiver of Claims, Rights and Interest" was filed by copies of payment of allowances, were never spurned by complainants-

above-named petitioners stating, among other things, that said petitioners are appellees." 25 The Solicitor General observes, on the other hand, that these alleged

waiving their claims, rights and interests against the respondents. documents were never presented at the hearing but surfaced only on

appeal. 26 Indeed, there is no reference in the Labor Arbiter's decision to these

ACCORDINGLY, let the above-entitled cases be DISMISSED in view of the documents, and apparently, the respondent firm entered the same in evidence at the

waiver made by the petitioners. 20 appeal level only. As we have declared, a party is barred from introducing fresh

matters at the appellate stage. Besides, and as the Solicitor General points out, "the

ECOLA awarded to petitioners in the decision of the Labor Arbiter include only those

Acting on these allegations, the respondent Commission, baring its clear bias for that pertain to them from the time of their dismissal up to July 1, 1982 " 27 the date the

management, ruled that the petitioners had waived their claims. Thus: Labor Arbiter ordered their reinstatement. 28 Accordingly, we rule the respondent

corporation liable for such unpaid claims.

xxx xxx xxx

Before Batas Blg. 70 29 was enacted into law, unfair labor practices were considered

With respect to the second issue, that is, whether or not the waiver of rights and administrative offenses, 30 and have been held akin to tort, 31 wherein damages are

interests executed by Fernando do so, 6 The G Lising, Odilon do so, 6 The G payable. We therefore not only order herein the reinstatement of the petitioners and

Lising, Jose C. Tiamzon, Ernesto Tuazon, Pedro Santos, Ruben Buela, Eduardo the payment of backwages (including cost-of-living allowances) to them, but impose

Alegado, Estrael Vino, Rogelio Manguerra, Edilberto Bingcang, Olimpio Gumin, as well moral and exemplary damages. With respect to backwages, we hold the

Leo Tropico, Orlando Nacu, Rodolfo T. Capitly and Juanito Suba, are valid, the respondent e.g. Gochangco, Inc. liable, in line with the recommendation of the

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 11

Solicitor General and in accordance with accepted practice, for backwages equivalent G.R. No. 90519 March 23, 1992

to three (3) years without qualification or deduction. 32

UNION OF FILIPINO WORKERS (UFW), petitioners, vs. NATIONAL LABOR

As for moral damages, we hold the said respondent liable therefor under the RELATIONS COMMISSION, SIMEX INTERNATIONAL INC., LILIA SANTANDER,

provisions of Article 2220 of the Civil Code providing for damages for "breaches of GEORGE SANTANDER and JOSEPH SANTANDER, respondents.

contract where the defendant acted fraudulently or in bad faith." We deem just and

proper the sum of P5,000.00 each in favor of the terminated workers, in the concept This Petition for Certiorari seeks to set aside the Decision of public respondent

of such damages. National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC), dated 26 August 1989, which

reversed the Decision of the Labor Arbiter, dated 27 June 1988, and sustained the

We likewise grant unto said workers another P5,000.00 each to answer for exemplary closure of private respondent company, SIMEX International Inc., as valid.

damages based on the provisions of Articles 2229 and 2231 and/or 2232 of the Civil

Code. For "act[ing] in gross and evident bad faith in refusing to satisfy the On 4 September 1987, a Petition for Direct Certification among the rank-and-file

[petitioners'] plainly valid, just and demandable claim[s] " 33 the respondent firm is workers of SIMEX was filed before the Med Arbiter, docketed as Case No. 00-09-634-

further condemned to pay attorney's fees. The Court considers the total sum of 87 (Petition for Direct Certification), with the hearing thereof set for 18 September

P20,000.00 fair and reasonable. 1987. These workers subsequently affiliated with petitioner Union of Filipino Workers

(UFW).

If only for emphasis, the new Constitution considers "labor as a primary social

economic force." 34 As the conscience of the government, it is this Court's sworn duty On 19 September 1987, thirty-six (36) workers of the "lumpia" department were not

to ensure that none trifles with labor rights. given their usual working materials and equipment for that day and, instead, were

asked to clean their respective working areas. Since these workers were employed

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED. The decision of the public respondent, the on a "pakiao" basis, they refused. Nevertheless, they still reported for work on 21

National Labor Relations Commission, is REVERSED and SET ASIDE. Judgment is September 1987 but to their surprise, they found out that SIMEX had removed all

hereby rendered: materials and equipments from their workplaces. The Union claims that its members

were, therefore, effectively locked out.

1. Ordering the private respondent, e.g. Gochangco, Inc., to REINSTATE the

terminated workers; From 1 October 1987 to 7 October 1987, sixteen (16) more workers from the other

departments were similarly refused employment. As a consequence, these workers,

2. Ordering the private respondent to PAY them backwages equivalent to three (3) through UFW, instituted a Complaint for Unfair Labor Practices and violation of labor

years without qualification or deduction; standard laws against SIMEX and its principal officers and stockholders, namely

private respondents Lilia, George and Joseph, all surnamed SANTANDER, docketed

as NLRC-NCR-00-09-03329-87 (for Illegal Dismissal/Lockout of 36 "lumpia"

3. Ordering it to PAY them the sum of FIVE THOUSAND (P5,000.00) PESOS EACH, department workers and 16 others, etc.).

as and for moral damages;

On 9 October 1987, however, SIMEX had filed a Notice of "Permanent

4. Ordering it to PAY them the sum of FIVE THOUSAND (P5,000.00) PESOS EACH, Shutdown/Total Closure of All Units of Operation in the Establishment" with the

as and for exemplary damages; and Department of Labor and Employment to take effect on 9 November 1987, allegedly

due to business reverses brought about by the enormous rejection of their products

5. Ordering it to PAY them the sum of TWENTY THOUSAND (P20,000.00) PESOS for export to the United States. This notice of closure rendered the Petition for Direct

as and for attorney's fees. Certification moot and academic. Notices of Closure were placed in conspicuous

places around the company premises.

This Decision is IMMEDIATELY EXECUTORY.

Meanwhile, in sympathy with their fifty-two (52) co-workers who were allegedly

Costs against the private respondent. illegally dismissed by SIMEX and in "protest to the continued acts of unfair labor

practices committed" by SIMEX, thirty-nine (39) other workers staged a picket outside

the company premises from 10 October 1987 to 27 October 1987. By reason thereof,

IT IS SO ORDERED. SIMEX's supposed offer of separation pay totalling P280,000.00 was withdrawn.

When these workers lifted their picket on 27 October 1987 and voluntarily reported for

work, SIMEX refused to give them their usual work. They were dismissed effective 1

November 1987.

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 12

Another Complaint for Unfair Labor Practice was, therefore, filed against the same P500,000.00 in cash and

respondents, this time involving the thirty-nine (39) workers who picketed the P50,000.00 PCIB check No. 496869 dated Sept. 9, 1989

company premises in sympathy with their other co-workers, docketed as NLRC-NCR- P50,000.00 PCIB check No. 496870 dated Dec. 9, 1989

11-03887-87 (for Unfair Labor Practice, Illegal Dismissal/Lockout of thirty-nine P50,000.00 PCIB check No. 496871 dated March. 9, 1990

[39]workers). It is this case that is the subject of this Petition for Certiorari. P50,000.00 PCIB check No. 496872 dated June 9, 1990

On 27 June 1988, the Labor Arbiter rendered his verdict declaring that the closure of in full and complete settlement of NLRC-NCR-CASE NOS. 00-09-03329-87, 00-

SIMEX was a mere subterfuge in order to discourage the formation of the union. The 11-3887-87 and 00-01-00255-88.

respondents, SIMEX and the SANTANDERs, were found guilty of unfair labor

practice and were ordered, jointly and solidarily, to reinstate the 39 workers without I undertake to take charge of obtaining the signatures of the proper officers of the

loss of seniority rights, benefits and privileges, with full backwages from 1 November union to sign the Motion to Dismiss in order to implement the full and final

1987 until such time that these workers are actually reinstated. They were also settlement of said cases between complainant and respondents.

ordered to pay ten per cent (10%) of the total awards as attorney's fees.

I further undertake and warrant that with this payment by the respondents, the

On appeal, the NLRC, in a Decision dated 28 August 1989, set aside the Labor complainant Union and each of their members, hereby RELEASE AND

Arbiter's Decision when it held that the "determination of the wisdom or expediency to DISCHARGE the SIMEX INTERNATIONAL INC., each (sic) Officers, agents and

close a department in a corporation, e.g., the 'lumpia' department in this case, due to representative (sic) fro any demands, claims and liabilities from any cause

financial reverses, is the sole prerogative of the corporation." It ruled that since whatsoever, arising out of their employment with the said respondents (sic)

SIMEX had filed a Notice of Closure on 9 October 1987 and had complied with the corporation.

requirements of the applicable rules and regulations when it posted in their main gate

the aforesaid Notice, its failure to accept the workers of UFW did not constitute unfair

labor practice considering that SIMEX had already closed the "lumpia" department. UFW maintains, however, that the settlement did not materialize because of its

Hence, SIMEX was merely ordered to pay the workers affected a separation pay objections as shown by the fact that it had not filed a Motion to Dismiss and Quitclaim

equivalent to one (1) month's salary for every year of service rendered. in this case.

Petitioner UFW has thus elevated its cause before us in this Petition for Certiorari, The issues for determination then are: 1) whether or not a compromise had been

seeking the reversal of the NLRC Decision, for having been rendered with grave reached by the parties; and 2) whether or not there was a valid closure of SIMEX that

abuse of discretion, and the reinstatement instead of the Decision of the Labor Arbiter entitled it to terminate the employment of its thirty-nine (39) employees. A plea is also

and its affirmance in toto. made that the individual private respondents SANTANDERs be dropped from the suit

since they only acted within the scope of their authority.

The public and private respondents in this case were required to file their respective

Comments. Since the Solicitor General adopted a position contrary to that of the We incline to the view that no valid compromise agreement was arrived at in this

NLRC, the Court required the latter to file its own Comment, which it has done. case.

After the Comments, Reply, Rejoinders and the parties' respective Memoranda were The alleged settlement involved three (3) cases, one of which charges alleged

submitted, private respondents SIMEX and the SANTANDERs filed a Manifestation, violation of labor standards. Compromise agreements involving labor standards cases

dated 10 December 1990 (p. 212, Rollo), signed by Atty. Julio F. Andres, Jr., stating must be reduced to writing and signed in the presence of the Regional Director or his

that after they had manifested to the Court on 9 December 1990 that they were duly authorized representative (Atilano v. De la Cruz, G.R. No. 82488, 28 February

adopting their Memorandum, they discovered that an "Acknowledgment Receipt and 1990, 182 SCRA 886). Section 8, Rule II of the Rules on the Disposition of Labor

Undertaking," dated 9 June 1989, had already been signed between private Standards Cases in the Regional Offices provides:

respondent George SANTANDER and petitioner's former counsel, Atty. Modesto S.

Mendoza, whereby this case as well as two (2) others had already been settled and Sec. 8. Compromise Agreement. — Should the party arrive at an agreement as

compromised. Thereby, this controversy has become moot and academic. Said to the whole or part of the dispute, said agreement shall be reduced [to] writing

Undertaking reads: and signed by the parties in the presence of the regional director or his duly

authorized representative.

I, MODESTO S. MENDOZA, . . ., have today RECEIVED FROM SIMEX

INTERNATIONAL, INC., through its Vice-President, MR. GEORGE The questioned "Acknowledgment Receipt and Undertaking" did not comply with this

SANTANDER, the following amounts: requisite. It was not, therefore, duly executed.

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 13

Even assuming arguendo that it was, Atty. Modesto Mendoza, counsel for petitioner year of service, whichever is higher. A fraction of at least six (6) months shall be

UFW, whose services were subsequently terminated, was not duly authorized to considered one (1) whole year. (Emphasis in text supplied).

enter into a compromise with SIMEX and the SANTANDERs. As aptly pointed out by

the Solicitor General, Article 1878 of the Civil Code provides that a Special Power of Under this provision, the closure of a business establishment is a ground for the

Authority is required before an agent can be authorized to enter into a compromise. It termination of the services of any employee unless the closing is for the purpose of

reads: circumventing the provisions of law. But, while business reverses can be a just cause

for terminating employees, they must be sufficiently proven by the employer (Indino v.

Art. 1878. Special powers of attorney are necessary in the following cases: NLRC, G.R. No. 80352, 29 September 1989, 178 SCRA 168).

xxx xxx xxx In the case at bar, SIMEX alleged that it suffered export rejections amounting to

$78,959.54 for 1985, $1,654.00 for 1986 and $28,414.11 for 1987, respectively. It

(3) To compromise, to submit questions to arbitration, to renounce the right to alleged that these export rejections resulted in huge financial losses to the company

appeal from a judgment, to waive objections to the venue of an action or to (Rollo, p. 96) so much so that remedial measures were instituted as suppliers

abandon a prescription already acquired. (Emphasis ours). hesitated to given the company their usual credit terms (ibid, p. 97).

No evidence was adduced that would show that the aforementioned counsel for UFW The audited financial statement of SIMEX, however, clearly depicted that for 1985

was authorized to enter into a compromise. Correspondingly, he cannot release and and 1986, the company actually derived retained earnings of P35,593.21 and P73,

discharge SIMEX and the SANTANDERs from their obligation. A perusal of the 241.25, respectively. The private respondents never refuted this fact. Instead, they

"Acknowledgment Receipt and Undertaking" reveals that no representative of UFW merely insisted that these export rejections resulted in heavy losses for the company.

signed the alleged settlement. These export rejections may have, indeed, contributed to a reduction of SIMEX's

earnings. The company, however, was not suffering from business losses, as

claimed, at the time of application for closure.

The fact that said counsel undertook to obtain the signatures of the proper officers of

UFW shows that his action was still subject to ratification by the union members. This

confirmation was never secured as shown by the fact that no motion for the dismissal Indeed, there is no question that an employer may reduce its work force to prevent

of the case at bar had been filed by UFW or on its behalf "in order to implement the losses. However, these losses must be serious, actual and real (Lopez Sugar

full and final settlement of said case," unlike in NLRC-NCR Case No. 00-01-00255-88 Corporation v. Federation of Free Workers, G.R. No. 75000-01, 30 August 1990, 189

where such a Motion had been filed. In an Affidavit, dated 6 May 1991 (p. 258, Rollo), SCRA 179). Otherwise, this "ground for termination would be susceptible to abuse by

Atty. Mendoza also declared that respondent George Santander had stopped the scheming employers who might be merely feigning business losses or reverses in

payment of the three (3) postdated checks, which statement has not been refuted by their business ventures in order to ease out employees (Garcia v. NLRC, G.R. No. L-

private respondents. 67825, 4 September 1987, 153 SCRA 639).

We now shift to the issue bearing on the legality of the closure of SIMEX. Article 283 In this regard, then, SIMEX failed to prove its claim. What were submitted as

(then Article 284) of the Labor Code provides: evidence were mere receipts of export rejections, nothing more. SIMEX never

adduced evidence that would reflect the extent of losses suffered as a result of the

export rejections, which failure is fatal to its cause.

Art. 283. Closure of the establishment and reduction of personnel. — The

employer may also terminate the employment of any employee due to the

installation of labor saving devices, redundancy, retrenchment to prevent losses The Notice of Closure filed by SIMEX had indicated that it will have a permanent

or the closing or cessation of operation of the establishment or undertaking shutdown and/or total closure of all its units of operation. This was not so. Workers

unless the closing is for the purpose of circumventing the provisions of this belonging to the Marketing and Export Divisions were never laid off. A SEC

Title, by serving a written notice on the workers and the Ministry of Labor and Certification, dated 4 February 1988, shows that SIMEX never applied for dissolution.

Employment at least one (1) month before the intended date thereof. In case of The Labor Arbiter also found as a fact that SIMEX continued to export its products,

termination due to the installation of labor saving devices or redundancy, the including "eggroll wrap," long after its target date of closure.

worker affected thereby shall be entitled to a separation pay equivalent to at least

his one (1) month pay or at least one (1) month pay for every year of service, In explaining this discrepancy, SIMEX merely alleged that not all its operations were

whichever is higher. In case of retrenchment to prevent losses and in cases of closed. Even on this score alone, therefore, private respondents' position must be

closures or cessation of operations of establishment and undertaking not due to rejected.

serious business losses or financial losses, the separation pay shall be

equivalent to one (1) month pay or at least one half (1/2) month pay for every These factors strongly give more credence to the Solicitor General and UFW's

contention that the alleged closure of business of SIMEX was "but a subterfuge to

LABOR LAW 2- SESSION 2 CASES Page 14

discourage formation of a union" and that SIMEX was guilty of union busting. To all

appearances, the company had filed a Notice of Closure simply to pre-empt the

employees from forming a union within the company.

The SANTANDERs' prayer that they be dropped from this case must also be rejected.

They should have adopted that recourse during the earlier stages. Moreover, UFW

has adequately shown that the individual private respondents were not only officers of

the company but its major stockholders as well (see Carmelcraft Corporation v.

NLRC, G.R. Nos. 90634-35, 6 June 1990, 186 SCRA 393).

Lastly, if SIMEX has not yet recovered the balance of the compromise money given to

then counsel for petitioner, its recourse is to file the appropriate civil or criminal case

against the latter. After all, in said counsel's Affidavit, he has stated that he is ready to