Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Appi Ajp 2007 07071079

Загружено:

Aaser AasdeИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Appi Ajp 2007 07071079

Загружено:

Aaser AasdeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Article

Systems Training for Emotional Predictability

and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for Outpatients With

Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized

Controlled Trial and 1-Year Follow-Up

Nancee Blum, M.S.W. Objective: Systems Training for Emo- analyzed. Subjects assigned to STEPPS

tional Predictability and Problem Solving plus treatment as usual experienced

(STEPPS) is a 20-week manual-based greater improvement in the Zanarini Rat-

Don St. John, M.A., P.A.C.

group treatment program for outpatients ing Scale for Borderline Personality Disor-

with borderline personality disorder that der total score and subscales assessing af-

Bruce Pfohl, M.D. combines cognitive behavioral elements fective, cognitive, interpersonal, and

and skills training with a systems compo- impulsive domains. STEPPS plus treat-

Scott Stuart, M.D. nent. The authors compared STEPPS plus ment as usual also led to greater improve-

treatment as usual with treatment as ments in impulsivity, negative affectivity,

Brett McCormick, M.A. usual alone in a randomized controlled mood, and global functioning. These dif-

trial. ferences yielded moderate to large effect

Jeff Allen, Ph.D. Method: Subjects with borderline person-

sizes. There were no differences between

groups for suicide attempts, self-harm

ality disorder were randomly assigned to

Stephan Arndt, Ph.D. acts, or hospitalizations. Most gains attrib-

STEPPS plus treatment as usual or treat-

uted to STEPPS were maintained during

ment as usual alone. Total score on the Za-

follow-up. Fewer STEPPS plus treatment

Donald W. Black, M.D. narini Rating Scale for Borderline Personal-

as usual subjects had emergency depart-

ity Disorder was the primary outcome

ment visits during treatment and follow-

measure. Secondary outcomes included

up. The discontinuation rate was high in

measures of global functioning, depres-

both groups.

sion, impulsivity, and social functioning;

suicide attempts and self-harm acts; and Conclusions: S T E P P S , an a dj u n c t i v e

crisis utilization. Subjects were followed 1 group treatment, can deliver clinically

year posttreatment. A linear mixed-effects meaningful improvements in borderline

model was used in the analysis. personality disorder-related symptoms

and behaviors, enhance global function-

Results: Data pertaining to 124 subjects

ing, and relieve depression.

(STEPPS plus treatment as usual [N=65];

treatment as usual alone [N=59]) were

(Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:468–478)

T he treatment of patients with borderline personality

disorder is challenging (1, 2). The use of medication has

acts (14, 15). STEPPS is easily learned and efficiently

delivered by therapists of varying educational and profes-

increased, but while several drugs have proven useful, sional backgrounds. The program supplements—but does

their benefit has been modest (3–4). A range of psycho- not replace—a patient’s ongoing treatment (e.g., medica-

therapies has been developed and several have garnered tion, individual therapy, case management). Data from

empirical support (5–12), including dialectical behavioral two uncontrolled studies have supported its use (16, 17).

therapy (5–7, 12), mentalization-based therapy (8, 9), cog- STEPPS is used in the United States (18) and was intro-

nitive behavioral therapy (10), schema-focused therapy duced in the Netherlands in 1998. By 2005, nearly 400

(11), and transference-focused therapy (12). Dutch therapists were trained in its use (18).

In 1995, Blum et al. developed Systems Training for In the present study, we report results of a 20-week ran-

Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) domized controlled trial and a 1-year follow-up. Outpa-

based on a program introduced by Bartels and Crotty (13). tients with borderline personality disorder were randomly

STEPPS is a group treatment that combines cognitive be- assigned to STEPPS plus treatment as usual or treatment as

havior elements and skills training with a systems compo- usual alone. We hypothesized the following: 1) STEPPS

nent for individuals with whom a patient regularly inter- plus treatment as usual would result in greater improve-

This article is featured in this month’s AJP Audio and is discussed in an editorial by Dr. Silk (p. 413).

468 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008

BLUM, ST. JOHN, PFOHL, ET AL.

ment in borderline traits, social functioning, global func- cient was 0.96 for the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Person-

tioning, and mood relative to treatment as usual alone; 2) ality Disorder total and 0.58 for the CGI severity ratings.

In addition to screening and baseline evaluations, subjects

STEPPS plus treatment as usual would result in fewer sui-

were assessed at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. The Client Satisfaction

cidal and self-harm acts and the use of fewer crisis re- Questionnaire-8 (32) was administered at week 20.

sources relative to treatment as usual alone; and 3) gains

resulting from STEPPS plus treatment as usual would be Treatment Assignment

maintained during the follow-up. Subjects were assigned by coin toss to either the STEPPS plus

treatment as usual group or treatment as usual alone group.

Whenever eight to 12 subjects were assigned to STEPPS plus

Method treatment as usual, they were notified that a group would begin.

Groups began a mean of 6.5 (SD=6.6) weeks after random assign-

Subjects ment. Eight treatment cohorts were recruited between 2002 and

2006.

Subjects with DSM-IV (19) borderline personality disorder

were recruited from the University of Iowa inpatient and outpa- STEPPS Program

tient psychiatric services (N=92); clinicians and mental health

centers in eastern Iowa (N=35); advertisements (N=29); word of STEPPS is a manual-based group treatment program for out-

mouth (N=8); and unspecified methods (N=8). We excluded sub- patients with borderline personality disorder that combines cog-

jects who 1) did not speak English; 2) had a psychotic or primary nitive behavioral elements with skills training; it does not include

neurological disorder; 3) were cognitively impaired; 4) had cur- individual therapy. The program involves 20 2-hour weekly ses-

rent (past month) substance abuse or dependence; or 5) partici- sions with two co-facilitators who follow a detailed lesson plan.

pated in STEPPS previously. Subjects were required to designate a Participants receive a packet of materials each week, including an

mental health professional and a friend or relative to serve as sys- agenda and homework assignments. STEPPS is systems-based in

tem members. The purpose was to ensure that an independent that family members, significant others, and health care profes-

mental health professional could be reached in a crisis and that a sionals are educated about borderline personality disorder and

friend or relative could participate in the systems component of instructed how best to interact with their relative or friend with

STEPPS. The designated individual was taught how to respond to the disorder. Participants are urged to share their notebooks and

the subject’s dysfunctional thoughts or behaviors. Subjects were lesson materials with system members.

not required to have recent suicidal or self-harm behavior. Sub- The STEPPS program has the following three main compo-

jects gave written informed consent according to procedures ap- nents: 1) psychoeducation about borderline personality disorder;

proved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. 2) emotion management skills training; and 3) behavior manage-

ment skills training. The first component teaches subjects to re-

Assessments place misconceptions about borderline personality disorder with

an awareness of the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that define

The diagnosis of borderline personality disorder was estab- it and to identify their own schemas (i.e., cognitive filters) that

lished using the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (20). drive their behaviors. The disorder is also reframed as an emo-

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (21) assessed tional intensity disorder, which patients find preferable to border-

current and lifetime DSM-IV axis I disorders. Efficacy assessments line personality disorder. The second component teaches the fol-

included the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Dis- lowing skills to better manage the cognitive and emotional effects

order (22) to assess affective disturbance, cognitive disturbance, of borderline personality disorder: distancing, communicating,

impulsivity, and disturbed relationships; the Borderline Evalua- challenging, distracting, and problem management. The third

tion of Severity Over Time (18) to assess thoughts, feelings, and be- component teaches the following behavioral skills, which sub-

haviors associated with borderline personality disorder; the Posi- jects are encouraged to master: goal setting, healthy eating be-

tive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (23) to assess positive haviors, sleep hygiene, regular exercise, leisure activities, health

and negative dispositions; the Beck Depression Inventory (24); the monitoring (e.g., medication adherence), avoiding self-harm, and

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (25); the Barratt Impulsiveness interpersonal effectiveness. A session-by-session description is

Scale (version 11a) (26); and the Social Adjustment Scale (27). Sui- provided in Table 1.

cide and self-harm behaviors, medication usage, physician visits, Sessions have the look and feel of a seminar. Participants sit at

other therapies, and crisis contacts were also assessed. a conference table facing a board. There is a short break between

Primary outcome was the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline the first and second hours. Each weekly session is organized

Personality Disorder total score. Zanarini Rating Scale for Border- around a particular skill. Some skills require more than one ses-

line Personality Disorder subscales were used as secondary effi- sion to teach. In addition to the use of a board and printed mate-

cacy measures. Other secondary measures included the rater-ad- rials, the program is facilitated by poetry, songs, art work, and re-

ministered Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Improvement and laxation exercises. Participants are encouraged to bring materials

Severity scales (28), patient CGI self-rating (28), Global Assess- or artwork to reinforce the skills and themes of the meetings.

ment Scale (29), Beck Depression Inventory (24), Symptom Participants are asked to monitor their thoughts, feelings, and

Checklist-90-Revised (25), Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (26), and behaviors over the course of the program; this enables them to

Social Adjustment Scale (27). The CGI and Global Assessment become aware of and to monitor improvements in the intensity

Scales were used in part because of their demonstrated utility in and frequency of their emotional episodes. They are introduced

medication studies of borderline personality disorder (30, 31). to the Emotional Intensity Continuum, a 1- to 5-point scale using

Secondary outcome measures also included crisis variables (hos- the metaphor of pots on a burner. At level 1, there is no heat under

pitalizations, emergency department visits, and crisis phone the pot; at level 5 the pot is boiling over. This allows participants

calls), suicide attempts, and self-harm acts. to recognize early warning signs of an impending outburst. New

To achieve reliability on interview measures, raters were skills become the tools to prevent the heat from getting too hot,

trained by Nancee Blum, who also provided ongoing supervision. thereby reducing the chance that the pot will boil over. With this

Excellent diagnostic agreement was achieved (kappa=1.0 for bor- and other metaphors, abstract concepts are made more concrete

derline personality disorder). The intraclass correlation coeffi- and understandable. As participants progress, they are asked to

Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 469

STEPPS FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER OUTPATIENTS

TABLE 1. Session-by-Session Description of Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for

Outpatients With Borderline Personality Disorder

Session Description

Session 1 Introduction of participants and co-facilitators.

Completion, scoring, and recording of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST) scale.

Review guidelines for participating in STEPPS program.

Review concept of borderline personality disorder, including diagnostic criteria and introduction of Emotional

Intensity Disorder as an alternate “diagnostic” label.

Identification of reinforcement team (members of support system with whom they choose to share information

about borderline personality disorder, the skills they are learning, and how the team can reinforce what they’ve

learned).

Each group member identifies his or her specific goals (e.g., personal, social, educational/vocational).

Session 2 Completion of the BEST. (From this point forward, participants complete the BEST prior to each subsequent session.)

Completion of schema questionnaire and education about schemas (cognitive filters) in borderline personality

disorder.

Session 3 Description of distancing from emotional intensity, and relaxation breathing; each subsequent session begins with

a different relaxation exercise.

Sessions 4 and 5 Introduction to the Emotional Intensity Continuum. These two sessions also teach the communicating of feelings,

physical sensations, thoughts, filters, behaviors, and action urges more accurately.

Beginning with session 5, the relaxation exercise is followed by a review of each participant’s use of the Emotional

Intensity Continuum and specific STEPPS skills.

Sessions 6–8 Teach the challenging of maladaptive filters by identifying common cognitive distortions and replacing them with

more accurate and functional alternative thoughts.

Sessions 9 and 10 Teach distracting behaviors and positive affirmations to reduce emotional intensity.

Sessions 11 and 12 Teach the management of problems using specific problem solving paradigms.

Session 13 Identify problematic lifestyle behaviors (eating, sleeping, exercise, etc.) and discuss the need for balance.

Participants complete a questionnaire to identify areas of difficulty. Each participant identifies a problem area on

which to work.

Session 14 Specific goals are set for one previously identified problematic behavior, which are worked on in the remaining

weeks.

Session 15 Healthy eating and sleep behaviors are reviewed.

Session 16 Healthy exercise, leisure, and physical health behaviors are reviewed.

Session 17 Skills to reduce self-harm behaviors are taught.

Participants use the Emotional Intensity Continuum to identify antecedents to self-harm and other abusive

behaviors.

Sessions 18 and 19 Discussion of interpersonal boundaries and solicitation of relationships.

Session 20 Comparison of initial and termination schema (i.e., cognitive filters) questionnaire.

Evaluation of the group’s progress and use of skills. Celebration of completion.

monitor the new skills employed to manage their emotional in- Treatment as Usual

tensity. Patients gradually become more aware of emotional trig-

Subjects assigned to either STEPPS plus treatment as usual or

gers that may lead to outbursts. to treatment as usual alone were encouraged to continue their

Participants are encouraged to continue with ongoing con- usual care, including individual psychotherapy, medication, and

comitant treatment. Those participating in individual therapy are case management. Subjects received no instructions or advice

asked to familiarize their therapist with STEPPS, thereby enabling about other pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatments.

all members of the treatment team to employ a consistent ap- Subjects assigned to treatment as usual alone could not attend

proach and terminology. Participants are encouraged to show a any STEPPS group until they completed the 20-week trial.

copy of the handouts to their therapist and to review their home-

work assignments during their individual sessions. Follow-Up

A 2-hour evening session is held for family members or signifi- At the end of the 20-week treatment period, subjects entered a

cant others as part of the program. These individuals are edu- 1-year follow up. Assessments were made at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and

cated about borderline personality disorder and how best to re- 12. These included the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over

spond to their relative or friend with the disorder. STEPPS Time, Beck Depression Inventory, PANAS, CGI severity and im-

attendees are encouraged to share their lessons with their indi- provement ratings, Global Assessment Scale, and Social Adjust-

vidual therapist and significant others. This constitutes the sys- ment Scale. Data on crisis variables, medication use, psychother-

tems component of the program. apy visits, suicide attempts, and self-harm acts were also

collected.

STEPPS was administered by two of the authors of the present

study (Ms. Blum and Mr. St. John). Adherence to the manual was Statistical Analysis

rated on a 5-point scale, with a score of 5 denoting excellent ad-

Subjects with at least one postbaseline assessment were in-

herence (unpublished data of Donald W. Black, 2002). A score of 4

cluded in the analyses. To test for treatment group imbalances,

(good) or higher was considered acceptable. Two Ph.D.-level psy- baseline demographic characteristics and clinical variables were

chologists who were not involved with the randomized controlled compared using Pearson’s chi-square tests or Student’s t tests.

trial but familiar with STEPPS rated 43 randomly selected video- A linear mixed-effects model was used for primary and second-

taped sessions. The mean adherence score was 4.4 (SD=0.8). ary outcomes. Each subject’s trajectory of scores from baseline to

Additional information about the STEPPS program may be week 20 was summarized with a subject-specific intercept and

found at www.steppsforbpd.com. The website contains a sum- slope, thus allowing STEPPS efficacy to be tested by examining the

mary of the program, literature references, author information, difference between the mean slopes of the two groups. To adjust for

and contact instructions. possible bias from informative right censoring (which occurs, for

470 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008

BLUM, ST. JOHN, PFOHL, ET AL.

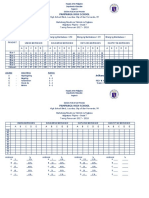

TABLE 2. Baseline Social, Demographic, and Clinical Characteristics of 124 Outpatients With Borderline Personality Disor-

der, by Treatment Assignment

Treatment Assignment

STEPPS Plus Treatment as Usual Treatment as Usual Alone All Subjects

Characteristic (N=65) (N=59) (N=124)

N % N % N %

Gender

Female 52 80 51 86 103 83

Male 13 20 8 14 21 17

Race/ethnicity

Caucasian 62 95 55 93 117 94

African American 1 2 2 3 3 2

Other 2 3 2 3 4 3

Marital status

Never married 27 42 23 39 50 40

Married/living together 21 32 20 34 41 33

Divorced/separated 17 26 16 27 33 27

Education

<High school 2 3 4 7 6 5

High school 10 15 15 25 25 20

Some college 38 59 27 46 65 52

College degree 9 14 11 19 20 16

Graduate degree 6 9 2 3 8 6

Employment

Employed 28 43 20 34 48 39

Disabled 18 28 14 24 32 26

Other (e.g., student) 19 29 25 42 44 35

Past psychiatric hospitalizationa 38 69 30 75 68 72

Prior suicide attempts 47 72 44 75 91 73

Prior self-harm 45 69 44 75 89 72

Current individual therapy 41 63 32 54 73 59

Current major depressive disorder 44 68 46 78 90 73

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

Age (years) 31.4 8.8 31.6 10.3 31.5 9.5

Psychotropic medications 3.0 2.5 2.7 2.1 2.9 2.3

Lifetime DSM-IV axis I disorders 4.8 2.4 5.0 2.6 4.9 2.5

DSM-IV personality disorders 3.1 1.7 3.7 1.9 3.4 1.8

DSM-IV borderline personality 7.6 1.3 7.7 1.2 7.6 1.2

disorder criteria

a Total N=95 (55 in STEPPS plus treatment as usual, 40 in treatment as usual alone).

example, when subjects with more favorable response are more emergency department visits, and crisis calls) was utilized (y). As-

likely to be assessed), last assessment time was used as a covariate suming a binomial model (y is a binomial random variable with

for intercepts and slopes. For the primary outcome variable (Za- parameters n and p) with logistic link function, we tested whether

narini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder total), last the probability of monthly utilization (p) differed for the groups.

assessment time was not related to baseline score (intercept) or Using the Cox proportional hazards model, the study groups were

level of improvement (slope), and therefore this adjustment had lit- compared on times to first suicide attempt and self-harm act.

tle effect on the test of STEPPS efficacy. To ensure that a significant Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (33). The linear

baseline difference with respect to avoidant personality disorder mixed-effects and repeated measure models were fit using the

did not confound the test of STEPPS efficacy, the disorder was used MIXED procedure; the binomial models were fit using the NL-

as a covariate for intercepts and slopes. Avoidant personality disor- MIXED procedure; and the Cox proportional hazards model was

der was associated with baseline severity (intercept) for the pri- fit using the PHREG procedure. All tests were performed using a

mary outcome but not level of improvement (slope), an adjust- two-sided significance level of p=0.05.

ment that had little effect on the test of STEPPS efficacy.

Group differences were also tested across the 1-year follow-up. Results

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) model was

used to compare group changes from week 20 with week 72 (1- One hundred seventy-two men and women 18 years

year follow-up). By utilizing the correlation of subjects’ responses

and older were screened; 165 were enrolled and randomly

over time, this model accommodates subjects with incomplete

data. The correlation of subjects’ responses was assumed to have assigned to STEPPS plus treatment as usual or treatment

a first-order autoregressive structure, which assumes that the cor- as usual alone. One hundred twenty-five subjects received

relation of a subject’s responses decreases as the time between the allocated interventions. Of these, data from 124 were

the assessments increases. For this analysis, week 20 was consid- analyzed (Figure 1). (One subject was excluded because of

ered the baseline. a primary neurological disorder.) The groups were bal-

Groups were compared on the use of crisis services throughout anced on baseline demographic and clinical variables (Ta-

the treatment and follow-up periods. For these variables, subjects

were asked to report utilization during the last month. For each

ble 2), except avoidant personality disorder was more fre-

subject, we counted the number of follow-up months (n) and quent in the treatment as usual alone group (66% versus

number of months for which each crisis service (hospitalizations, 45%; χ2=5.8, df=1, p=0.016).

Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 471

STEPPS FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER OUTPATIENTS

FIGURE 1. Consort Diagram of Patient Flow in the Random- greater relative to the treatment as usual alone group for

ized Controlled Trial the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disor-

der total and all four subscales, CGI severity and improve-

Assessed for Excluded for ment ratings, Global Assessment Scale, Borderline Evalua-

eligibility (N=172) not meeting tion of Severity Over Time (thoughts/feelings subscale),

inclusion

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, PANAS (negative affectivity

criteria (N=7)

subscale), Beck Depression Inventory, Symptom Checklist-

90-Revised (depression, psychoticism, and global severity

Randomly assigned to STEPPS subscales), and Social Adjustment Scale (social/leisure

plus treatment as usual or to

treatment as usual alone (N=165)

subscale and total score). For other outcomes, improve-

ment observed in the STEPPS plus treatment as usual

group was greater than the treatment as usual alone group,

Allocated to STEPPS plus Allocated to treatment but differences were not statistically significant.

treatment as usual (N=93) as usual alone (N=72)

Effect sizes for the STEPPS program at 20 weeks repre-

sent group differences in mean improvement divided by

Received Did not Received Did not the pooled standard deviations at baseline. While some

allocated receive allocated receive

allocated allocated assessment scales were reverse-coded (lower scores more

intervention intervention

(N=66) intervention (N=59) intervention favorable), we report all effect sizes in a positive direction.

(N=27) (N=13) For the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality

Disorder total, estimated effect size was 0.84, indicating a

Excluded because of large effect of the STEPPS program on the primary out-

primary neurological come. For secondary outcome measures, effect size esti-

disorder (N=1)

mates ranged from 0.12–1.09. Generally, those of 0.50 and

greater were statistically significant.

Included in data analysis Included in data analysis

(N=65): (N=59): Figure 2 shows estimated means over the treatment pe-

Completed intervention Completed intervention riod for the primary and selected secondary outcomes.

(N=45) (N=51)

Lost to follow-up (N=12)

Improvements for the STEPPS plus treatment as usual

Lost to follow-up (N=8)

Discontinued group appear to be monotonic and roughly linear. Im-

intervention (N=8): provements for the treatment as usual alone group appear

Lack of efficacy (N= 2)

Other (N=6)

mostly confined to the first half of the treatment period.

Subjects randomly assigned to STEPPS plus treatment

as usual had greater change in CGI severity and improve-

ment ratings relative to those randomly assigned to treat-

Forty-five (69%) subjects assigned to STEPPS plus treat- ment as usual alone. Using each subject’s last observation

ment as usual and 51 (86%) subjects assigned to treatment within the treatment period, those randomly assigned to

as usual alone completed the week 20 assessment (χ2=5.2, STEPPS plus treatment as usual were more likely to be

df=1, p=0.022). Baseline variables—age, gender, severity rated “very much” or “much” improved (40.0% versus

(Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time), and depres- 5.1%; χ2=21.0, df=1, p<0.001); subjects’ own global self-rat-

sion (Beck Depression Inventory)—were not predictive of ings showed similar results, with 58.5% of STEPPS plus

having at least one postbaseline assessment or early dis- treatment as usual recipients rating themselves as “very

continuation. Subjects completed a mean of 4.2 (SD=1.3) much” or “much” improved, compared with 22.0% for

assessments, with no significant differences between those assigned to treatment as usual alone (χ2=16.9, df=1,

treatment conditions (Mann-Whitney test: χ2=1.6, df=1, p<0.001). STEPPS plus treatment as usual recipients were

p=0.213). Overall, 82 (66%) subjects were assessed at least more likely to reach the clinically relevant Global Assess-

once during the 1-year follow-up. During follow-up, the ment Scale cutoff (>60) (18.5% versus 5.1%; χ2=5.2, df=1,

mean number of assessments was 3.0 (SD=1.6) for STEPPS p=0.023).

plus treatment as usual recipients and 2.8 (SD=1.3) for

treatment as usual alone recipients (Mann-Whitney test:

Assessment of Efficacy: 1-Year Follow-Up

χ2=0.4, df=1, p=0.549). STEPPS recipients attended a mean There were no statistically significant group differences

of 12.9 (SD=5.4) group treatment sessions. across the 1-year follow-up (Table 4), suggesting that treat-

ment period gains attributed to STEPPS were maintained.

Assessment of Efficacy: Treatment Period Because not all subjects were assessed through the follow-

STEPPS plus treatment as usual recipients improved up period, these analyses were less powerful than the pri-

from baseline through week 20 on primary and secondary mary analyses through week 20.

outcome measures (Table 3). The mean rate of change for Using each subject’s last observation within the follow-

the STEPPS plus treatment as usual group was significantly up period, those subjects randomly assigned to STEPPS

472 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008

BLUM, ST. JOHN, PFOHL, ET AL.

TABLE 3. Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures in Outpatients With Borderline Personality Disorder Randomly

Assigned to STEPPS Plus Treatment as Usual or Treatment as Usual Alone

Treatment Assignment

STEPPS Plus Treatment Treatment as Usual

as Usual (N=65) Alone (N=59)a Analysis of Difference in Rate of Change

Outcome Measure Mean SD/SEb Mean SD/SEb F df p Effect Sizec SE

Primary measure

Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline

Personality Disorder (total score) 11.0 1, 89 0.001 0.84 0.25

Baseline 18.9 6.8 17.3 7.0

Week 20 9.8 1.0 13.4 1.0

Secondary measures

Affective subscaled 7.6 1, 89 0.007 0.70 0.25

Baseline 10.8 2.7 10.1 2.8

Week 20 3.9 0.4 4.9 0.4

Cognitive subscaled 5.1 1, 89 0.027 0.51 0.23

Baseline 6.1 2.3 6.2 2.2

Week 20 2.0 0.3 3.0 0.3

Impulsivity subscaled 6.9 1, 89 0.010 0.65 0.25

Baseline 5.0 2.1 4.3 2.0

Week 20 1.9 0.3 2.3 0.3

Disturbed relationships subscaled 5.1 1, 88 0.026 0.61 0.27

Baseline 6.0 2.0 5.8 2.0

Week 20 2.2 0.3 3.2 0.3

CGI severity rating 14.1 1, 398 <0.001 0.75 0.20

Baseline 5.1 0.8 4.9 0.9

Week 20 4.4 0.1 4.7 0.1

CGI improvement rating 11.6 1, 277 <0.001 1.09 0.32

Baseline 3.8 1.0 4.0 1.1

Week 20 2.7 0.2 3.8 0.2

CGI patient self-rating 9.0 1, 254 0.003 0.90 0.30

Baseline 3.6 1.3 3.7 1.4

Week 20 2.4 0.2 3.3 0.2

Global Assessment Scale 12.1 1, 84 <0.001 0.65 0.19

Baseline 39.7 11.2 39.6 11.4

Week 20 50.5 1.6 43.5 1.6

Thoughts/feelingse 4.9 1, 379 0.027 0.51 0.23

Baseline 23.1 6.6 23.6 7.7

Week 20 18.7 1.0 20.6 1.1

Negative behaviorse 0.3 1, 375 0.578 0.12 0.22

Baseline 9.3 3.3 9.6 4.3

Week 20 8.2 0.5 7.9 0.5

Positive behaviorse 2.6 1, 368 0.110 0.41 0.26

Baseline 8.5 2.7 8.6 2.8

Week 20 10.1 0.4 9.3 0.4

Total scoree 3.5 1, 364 0.063 0.47 0.25

Baseline 39.0 9.7 39.8 12.6

Week 20 31.8 1.7 34.1 1.8

Positive affectivity (PANAS) 0.6 1, 374 0.440 0.15 0.19

Baseline 21.6 9.3 22.3 7.9

Week 20 23.4 1.1 22.4 1.1

Negative affectivity (PANAS) 4.3 1, 376 0.038 0.43 0.21

Baseline 28.9 9.4 29.9 9.0

Week 20 23.6 1.2 26.1 1.2

Beck Depression Inventory 4.6 1, 377 0.033 0.50 0.23

Baseline 29.0 11.6 29.7 15.0

Week 20 22.0 2.0 25.8 2.0

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale 9.0 1, 80 0.004 0.54 0.18

Baseline 80.6 12.6 77.4 12.8

Week 20 72.7 1.8 76.8 1.8

Sympton Checklist-90-Revised Global

Severity Indexf 4.8 1, 78 0.031 0.44 0.20

Baseline 16.0 7.2 16.8 6.0

Week 20 12.5 1.0 14.9 1.1

Social Adjustment Scale total scoref 3.5 1, 80 0.065 0.43 0.23

Baseline 27.8 5.0 28.2 5.0

Week 20 24.6 0.8 26.3 0.8

a Estimated mean and standard error from linear mixed-effects model adjusted for last assessment time and avoidant personality disorder. All

subjects with postbaseline assessment contributed to the estimation of baseline and week 20 means.

b Standard deviation was used at baseline, and standard error was used at week 20.

c Effect size is estimated as the group difference in week 20 mean improvement divided by the pooled standard deviation at baseline.

d From the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder.

e From the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time scale.

f To facilitate the reporting of significant digits, we scaled this measure by multiplying item means by 10.

Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 473

STEPPS FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER OUTPATIENTS

FIGURE 2. Mean Primary and Secondary Outcome Measure Scoresa

Subjects in data analysis of

treatment as usual alone (N=59) 40

19

Borderline Personality Disorder

Subjects in data analysis of STEPPS

Borderline Evaluation of

Zanarini Rating Scale for

plus treatment as usual (N=65)

Mean Total Score on

38

Severity Over Time

Mean Total Score on

17

36

15

34

13

32

11

30

9

5.25 30

Beck Depression Inventory

Impression Severity Rating

Mean Total Score on

Mean Clinical Global

28

5.00

26

4.75

24

4.50

22

4.25 20

Baseline 4 8 12 16 20 Baseline 4 8 12 16 20

Time (weeks) Time (weeks)

a The Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder was obtained at baseline, week 8, and week 20. The Borderline Evaluation of

Severity Over Time, CGI ratings, and Beck Depression Inventory were obtained at baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20.

plus treatment as usual were still more likely to be rated psychotherapy at baseline. These percentages remained

“very much” or “much” improved (40.0% versus 15.6%; χ2= relatively static during the 20-week treatment period.

5.5, df=1, p=0.019). However, subjects’ global self-ratings

Indirect Indicators of Efficacy

were not significantly different during the follow-up, with

55.1% of STEPPS plus treatment as usual recipients rating Subjects were asked to report crisis care utilization

within the last month. Because subjects varied in their

themselves “very much” or “much” improved, compared

number of assessments, we report utilization statistics in

with 43.8% of those assigned to treatment as usual alone

terms of the number of months per year in which utiliza-

(χ2=1.0, df=1, p=0.318). Within the follow-up period, sub-

tion occurred. Thus, for example, we can distinguish a

jects in STEPPS plus treatment as usual were still more

subject with three utilizations over 3 months (i.e., 12

likely to reach the Global Assessment Scale score cutoff

months per year with utilization) from a subject with three

(>60) (28.0% versus 9.7%; χ2=3.9, df=1, p=0.049).

utilizations over 6 months (i.e., 6 months per year with uti-

Medication and Individual Psychotherapy lization). Overall, 35 (28.2%) subjects had at least one hos-

pitalization during the treatment period or follow-up.

Ninety percent of subjects reported at least one psycho- Subjects randomly assigned to STEPPS plus treatment as

tropic medication at baseline. Antidepressants were re- usual averaged 1.13 months per year during which hospi-

ported by 42 (65%) of the STEPPS plus treatment as usual talization occurred, and subjects randomly assigned to

recipients and 33 (56%) of the treatment as usual alone treatment as usual alone averaged 1.24; the difference was

group (χ2=1.0, df=1, p=0.323). Psychotropic usage signifi- not significant (binomial test: p=0.670). In addition, 43

cantly decreased during the 20-week treatment period for (34.7%) subjects had at least one emergency department

both groups (from 2.9 to 1.3 medications per subject), but visit during the treatment period or follow-up. Subjects

there was no group difference in level of change (Mann- randomly assigned to STEPPS plus treatment as usual av-

Whitney test: χ2=0.1, df=1, p=0.782). Thus, medication us- eraged 0.97 months per year with at least one emergency

age did not confound study results. Additionally, 63% of department visit, and subjects randomly assigned to treat-

STEPPS plus treatment as usual subjects and 54% of treat- ment as usual alone averaged 1.52; the difference was sig-

ment as usual alone subjects were receiving individual nificant (binomial test: p=0.040). Finally, 60 (48.4%) sub-

474 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008

BLUM, ST. JOHN, PFOHL, ET AL.

TABLE 4. Follow-Up Comparison of Outcome Measures in Outpatients With Borderline Personality Disorder Randomly As-

signed to STEPPS Plus Treatment as Usual or Treatment as Usual Alone

Treatment Assignment

STEPPS Plus Treatment as Treatment as Usual Alone

Usual (N=65) (N=59) Analysis

Outcome Measure Meana SE Meana SE F df p

CGI severity rating 0.1 1, 761 0.759

Week 20 4.3 0.1 4.8 0.1

1 year 4.4 0.2 4.9 0.2

CGI improvement rating 1.4 1, 616 0.240

Week 20 2.7 0.2 3.9 0.2

1 year 3.1 0.2 3.8 0.3

CGI patient self-rating 3.6 1, 572 0.058

Week 20 2.4 0.2 3.3 0.2

1 year 2.8 0.3 2.7 0.4

Global Assessment Scale 0.1 1, 427 0.743

Week 20 50.0 1.6 43.0 1.6

1 year 53.0 2.0 47.1 2.7

Thoughts/feelingsb 2.4 1, 718 0.121

Week 20 18.3 1.1 20.9 1.1

1 year 20.5 1.4 18.8 2.1

Negative behaviorsb 0.1 1, 714 0.783

Week 20 7.9 0.5 8.0 0.5

1 year 7.9 0.7 7.5 1.0

Positive behaviorsb 0.3 1, 704 0.587

Week 20 9.9 0.4 9.4 0.4

1 year 10.2 0.6 9.1 0.8

Total scoreb 0.7 1, 700 0.410

Week 20 31.3 1.8 34.5 1.8

1 year 33.0 2.3 32.4 3.4

Positive affectivity (PANAS) 0.2 1, 710 0.687

Week 20 23.5 1.3 23.0 1.3

1 year 25.1 1.7 26.0 2.5

Negative affectivity

(PANAS) 0.1 1, 713 0.750

Week 20 23.4 1.3 26.2 1.3

1 year 25.8 1.8 27.4 2.6

Beck Depression Inventory 0.5 1, 712 0.462

Week 20 22.1 2.0 25.3 2.0

1 year 24.0 2.6 23.4 3.8

Social Adjustment Scale

total scorec 0.8 1, 415 0.371

Week 20 25.2 0.8 26.2 0.8

1 year 24.3 1.0 27.1 1.5

a Estimated mean if groups were balanced on avoidant personality disorder and last visit time (hence the week 20 mean estimates will differ

somewhat from those presented in Table 3). All subjects with follow-up assessment (N=50 for STEPPS plus treatment as usual, N=32 for treat-

ment as usual alone) contributed to the estimation of week 20 and week 72 means.

b From the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time scale.

c To facilitate the reporting of significant digits, we scaled this measure by multiplying item means by 10.

jects made at least one crisis call during the treatment and the mean was 16.6. Using the Cox proportional haz-

period or follow-up. Subjects randomly assigned to ards model, treatment group was not associated with time

STEPPS plus treatment as usual averaged 2.49 months per to first suicide attempt (χ2<0.1, df=1, p=0.994) or first self-

year during which at least one crisis call was made, and harm act (χ2<0.1, df=1, p=0.902).

subjects randomly assigned to treatment as usual alone Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 total scores at week

averaged 2.31; the difference was not significant (binomial 20 were significantly higher for the STEPPS plus treatment

test: p=0.603). as usual group relative to the treatment as usual alone

group (t=4.7, df=71, p<0.001), with means of 28.2 (SD=4.9)

Suicide attempt and self-harm data were available for

and 22.6 (SD=5.2), respectively, indicating greater satisfac-

108 of the 124 subjects. Suicide attempts were reported by

tion.

24 subjects (22.2%), and self-harm acts were reported by

56 (45.2%) subjects during treatment and follow-up.

Nearly all who attempted suicide (88%) also reported self- Discussion

harm acts. Among those who attempted suicide, the me- STEPPS plus treatment as usual was superior to treat-

dian number of attempts was 1.75 per year, and the mean ment as usual alone in the treatment of outpatients with

was 2.60. Among those who reported acts of deliberate borderline personality disorder across a spectrum of ill-

self-harm, the median number of acts was 9.8 per year, ness-specific and global measures. These results are en-

Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 475

STEPPS FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER OUTPATIENTS

Patient Perspective

“Jenny,” a 43-year-old married, Caucasian woman, was and none during the past year. Likewise, there was one

referred to the research study by her psychiatrist. She had non-serious suicide attempt during the program and none

a history of physical and emotional abuse in childhood, during the following 2 years, a record for her.

repetitive self-harm (mainly cutting and head banging), With STEPPS, Jenny learned new emotion and behavior

and multiple non-serious suicide attempts. She had been management skills. When she reached a “5” on the

psychiatrically hospitalized more than 200 times, and she Emotional Intensity Continuum (indicating that she felt out

had from 5 to 10 admissions annually in recent years. She of control), the group facilitators and members helped her

was taking nefazodone, quetiapine, gabapentin, and identify the cognitive filters and related distorted thoughts

carbamazepine for symptom management and was that were triggered; she was then encouraged to choose

engaged in individual psychotherapy. She screened and implement a skill to reduce her emotional intensity.

positive for recurrent major depression, posttraumatic Social undesirability, for example, was a strong cognitive

stress disorder, past panic disorder, and past anorexia filter that often led to acts of self-harm. In response, Jenny

nervosa in addition to her borderline personality disorder. learned to use the skills of distancing and distracting to

Jenny was randomly assigned to the active treatment decrease her emotional intensity and to use the skill of

arm and attended all 20 STEPPS sessions, despite having to communicating her thoughts to others and accepting

drive a considerable distance and experiencing financial, feedback. As the group progressed, she was able to

marital, and school-related stressors. Her reinforcement challenge her cognitive distortions more effectively and

team consisted of her psychiatrist and therapist but respond to stressful situations in a more positive way.

eventually expanded to include other members of the Jenny has since completed her schooling and is

group. She gradually became less symptomatic. For employed as a part-time school teacher and mental health

example, her Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time advocate. She uses her STEPPS skills on a daily basis:

score fell from 50 at baseline to 17 at week 20. Instead of “Although I often feel like hurting myself, I rarely act

near monthly hospitalizations, there were only three out....It’s much easier for me to bring myself down to a

during the STEPPS program, two during the following year, lower intensity level, often without the help of others.”

couraging because they suggest that a relatively brief Importantly, improvements were generally maintained

adjunctive program can deliver clinically meaningful ben- during the follow-up, suggesting that subjects learned new

efits to persons with this disorder and improve their qual- skills that they used beyond the treatment period to en-

ity of life. STEPPS now joins several other treatment pro- hance their quality of life. Nonetheless, there was regres-

grams supported by empirical evidence and is a reminder sion in some scores during the follow-up for STEPPS re-

that earlier pessimism regarding the treatment of border- cipients. Without the support and structure of the group,

line personality disorder was misplaced (5–12). mild regression may be inevitable in some persons.

This treatment program helped subjects to better un- Subjects assigned to STEPPS plus treatment as usual

derstand their personality disorder and gave them skills to had moderate to high levels of satisfaction with the pro-

cope with it. It may also have provided social support, gram based on their Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8

hope, and therapeutic alliance, which are common factors scores, findings congruent with our preliminary data (16).

that may be responsible for benefit from many forms of Of course, these ratings were obtained from subjects who

therapy (34–36). Further, our test of STEPPS employed fea- completed the treatment study, and those who did not

tures of an effectiveness study suggesting that STEPPS may have been less satisfied.

provides “real-world” benefit. For example, subjects were We were unable to confirm our a priori hypotheses re-

allowed to take psychotropic medication or receive indi- garding a reduction in suicidal and self-harm acts during

vidual therapy and case management. the 20-week treatment or follow-up, although there were

STEPPS led to broad-based improvements that in- no suicides. Additionally, while there was less crisis utiliza-

cluded the affective, cognitive, impulsive, and disturbed tion among those individuals receiving STEPPS, only the

relationship domains assessed by the Zanarini Rating reduction of emergency department visits was statistically

Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder; it also had a ro- significant. It may be that a positive effect on these behav-

bust antidepressant effect. Impulsivity, as measured by iors requires more than a 20-week program or that more

the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, was significantly reduced, intensive follow-up is needed. To this end, we have devel-

as were negative thoughts and feelings and negative affec- oped an adjunctive program designed to follow STEPPS,

tivity, the latter findings indicating that STEPPS recipients which we plan to investigate. Reductions in crisis utiliza-

were less likely to feel hopeless and helpless or to have tion, suicide attempts, and self-harm acts reported by

negative self-impressions. These changes reflect the em- other researchers have generally followed at least 12 to 18

phasis of the program in that subjects are taught to regu- months of active treatment (6–10). In addition, unlike

late their intense emotions and maladaptive behaviors. some studies (5, 6), we did not require subjects to be sui-

476 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008

BLUM, ST. JOHN, PFOHL, ET AL.

cidal at intake, and the low base rate of suicidal behaviors Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA 52242; donald-

black@uiowa.edu (e-mail).

may have made it difficult to show a treatment effect.

Dr. Black has received research support from Shire and Forest Labo-

There are several methodological limitations. First, we ratories; speaker’s bureau honoraria from Pfizer; and honoraria for

experienced a relatively high discontinuation rate. High other consulting from Forest Laboratories and Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Mr. St. John has received honoraria for consulting from AstraZeneca

drop-out rates are the bane of borderline personality disor- and Wyeth. Ms. Blum, Mr. St. John, and Dr. Pfohl have received royal-

der treatment trials. Bateman and Fonagy (8, 9) claimed a ties from Ms. Blum’s books for sales of the STEPPS CD-ROM. Drs. Allen,

rate of only 12%, as did Linehan et al. (6) in their recent di- Arndt, and Stuart and Mr. McCormick report no competing interests.

Supported by grant MH-63746 from NIMH (Dr. Black).

alectical behavioral therapy trial, yet substantially higher

The authors thank Wayne Bowers, Ph.D., and Scott Temple, Ph.D.,

rates have been reported by others. Verheul et al. (7) re- for their contributions to the study. The authors also thank Jo Ann

ported that 34 of 58 subjects (59%) assigned to dialectical Franklin, B.A., and Rebecca Hansel for data collection and data en-

try; Peggy Loveless, Ph.D., for help with data analysis; and Russell

behavioral therapy or treatment as usual dropped out. Noyes, M.D., for editorial suggestions.

While we encouraged patients to remain in the study, we Clinical Trials Registry number 00055315.

neither sought a commitment nor made a systematic at-

tempt to reduce nonattendance. Most subjects assigned to

STEPPS plus treatment as usual were not regular attendees References

of our clinic, and lack of “clinic loyalty” may have contrib- 1. Paris J: Social Factors in Personality Disorders: A Biopsychoso-

uted to dropping out. Additionally, for some subjects, cial Approach to Etiology and Treatment. New York, Cam-

travel to Iowa City for the program, particularly during win- bridge University Press, 1996

ter months, may have played a role. Subjects assigned to 2. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guidelines for the

Treatment of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder.

treatment as usual alone only had to complete periodic as-

Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158(suppl 1):1–52

sessments, often conducted by telephone. While we in- 3. Soloff PH: Psychopharmacology of borderline personality dis-

tended to conduct blind assessments, we found it nearly order. Psychiatr Clin North Am: 2000; 23:169–191

impossible to maintain blindness. The convergence of 4. Zanarini MC: Update on pharmacotherapy of borderline per-

both rater- and patient-administered scales suggests that sonality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2004; 6: 66–70

this may not have been an important deficiency. 5. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL:

Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal bor-

Another concern is the possible confounding of results derline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060–1064

by psychotropic medication. Zanarini (4) noted that 6. Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ,

nearly all patients treated for borderline personality disor- Heard HL, Korslund KE, Tutek DA, Reynolds SK, Lindenboim N:

der receive psychotropic medication. This was true of our Two year randomized controlled trial and follow up of dialecti-

cal behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behav-

subjects. Yet, there were no differences between groups in-

iors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry

dicating that results favoring STEPPS plus treatment as 2006; 63:757–766

usual were not because of medication. Similarly, individ- 7. Verheul R, Van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, De Ridder MAJ,

ual psychotherapy did not appear to confound the results. Stijnen T, Van den Brink W: Dialectical behavior therapy for

The paucity of men and minorities does not allow firm women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month ran-

domized clinical trial in the Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry 2003;

conclusions about the effectiveness of STEPPS in these 182:135–140

groups. Nor does the study design allow conclusions 8. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in

about the effectiveness of STEPPS relative to other man- the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a random-

ual-based treatment programs. Additionally, the fact that ized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1563–1569

we did not seek subjects with recent suicidal or self-harm 9. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Treatment of borderline personality dis-

order with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization:

behaviors limits comparison with studies that have ac-

an 18-month follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:36–42

tively recruited such persons (5, 6, 10). 10. Davidson K, Norrie J, Tyrer P, Gumley A, Tata P, Murray H,

Additional trials of STEPPS by independent research Palmer S: The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for

groups and testing STEPPS in other patient populations borderline personality disorder: results from the Borderline

Personality Disorder Study of Cognitive Therapy (BOSCOT) trial.

should be considered. Future studies should also address

J Person Disord 2006; 20:450–465

premature discontinuation and develop strategies to min-

11. Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, van Tilburg W, Dirksen

imize this limitation. C, van Asselt T, Kremers I, Nadort M, Arntz A: Outpatient psy-

chotherapy for borderline personality disorder-randomized

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiat- trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused ther-

ric Association, San Diego, Calif., May 2007, and the 10th Meeting of apy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:649–658

the International Society for the Study of Personality Disorders, 12. Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF: Evaluating

Hague, the Netherlands, Sept. 2007. Received July 9, 2007; revisions three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multi-

received Oct. 8 and Nov. 19, 2007; accepted Nov. 26, 2007 (doi: wave study. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:922–928

10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071079). From the Department of Psychia-

13. Bartels N, Crotty T: A Systems Approach to Treatment: The Bor-

try, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine,

derline Personality Disorder Skill Training Manual. Winfield, Ill,

Iowa City, Iowa; Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Health

Care, Iowa City, Iowa; and the Department of Biostatistics, University EID Treatment Systems, Inc, 1992

of Iowa College of Public Health, Iowa City, Iowa. Address correspon- 14. Blum N, Bartels N, St. John D, Pfohl B: STEPPS: Systems Training

dence to Dr. Black, Psychiatry Research / 2-126b MEB, University of for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving: Group Treat-

Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 477

STEPPS FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER OUTPATIENTS

ment for Borderline Personality Disorder. Coralville, Iowa, 25. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R Administration, Scoring, and Proce-

Blum’s Books, 2002 dures Manual II. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometric Research,

15. Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, St. John D: The STEPPS group treat- 1983

ment program for outpatients with borderline personality dis- 26. Barratt E: Anxiety and impulsiveness related to psychomotor

order. J Contemp Psychotherapy 2004; 34:193–210 efficiency. Percept Mot Skills 1959; 9:191–198

16. Blum N, Pfohl B, St. John D, Monahan P, Black DW: STEPPS: A 27. Weissman MM, Bothwell S: Assessment of Social Adjustment by

cognitive behavioral systems based group treatment for outpa- Patient Self-Report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1111–1115

tients with borderline personality disorder: a preliminary re- 28. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology.

port. Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:301–310 Washington, DC, United States Department of HEW Publica-

17. Freije H, Dietz B, Appelo M: Behandling van de borderline per- tions, 76–338, 1976, pp 217–222

soonlijk heidsstoornis met de vers: de vaardigheidstraining 29. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment

emotionele regulatiestoornis. Direct Therapies 2002; 4:367– Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric

378 disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771

18. Van Wel B, Kockmann I, Blum N, Pfohl B, Black DW, Heester- 30. Cowdry RW, Gardner DL: Pharmacotherapy of borderline per-

man W: STEPPS group treatment for borderline personality dis- sonality disorder: alprazolam, carbamazepine, trifluoperazine,

order in the Netherlands. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2006; 18:63–67 and tranylcypromine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:111–119

19. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical 31. Benedetti F, Sforzini L, Colombo C, Maffei C, Smeraldi E: Low-

Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. Washington, DC, dose clozapine in acute and continuation treatment of severe

American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994 borderline personality disorder. J Clin Pychiatry 1998; 59:103–

20. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M: Structured Interview for DSM- 107

IV Personality (SIDP-IV). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric 32. Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK: The UCSF Client Satisfaction Ques-

Publishing, 1997 tionnaire (CSQ) Scales: the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8,

21. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Inter- in Psychological Testing: Treatment Planning and Outcome As-

view for DSM-IV. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, sessment, 2nd edition. Edited by Maruish ME. Hillsdale, NJ, Er-

Biometrics Research, 1994 lbaum, 1999

22. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Fran- 33. SAS: SAS/STAT User’s Guide: Version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute,

kenburg FR, Hennen J: Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Per- Inc, 1999

sonality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV 34. Gabbard GO: Do all roads lead to Rome? New findings on bor-

borderline psychopathology. J Person Disord 2003; 17:233– derline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:853–

242 855

23. Watson D, Clark LA: The PANAS-Manual for the Positive and 35. Frank JD, Frank JB: Persuasion and Healing: A Comparative

Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form. Iowa City, Univer- Study of Psychotherapy. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1991

sity of Iowa, 1994 36. Wampold BE: The Great Psychotherapy Debate: Models, Meth-

24. Beck AT: Depression Inventory. Philadelphia, Philadelphia Cen- ods, and Findings. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

ter for Cognitive Therapy, 1978 Publishers, 2001

478 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 165:4, April 2008

Вам также может понравиться

- Trading SecretsДокумент99 страницTrading SecretsGary100% (3)

- STEPPS For NEA-BPD Call-In Series June 8 2014 - Part 1Документ24 страницыSTEPPS For NEA-BPD Call-In Series June 8 2014 - Part 1Aaser Aasde100% (2)

- Baby Romper Pattern and Sewing Tutorial 2014Документ18 страницBaby Romper Pattern and Sewing Tutorial 2014Carolina Ribeiro100% (1)

- Treatment For Eating DisordersДокумент13 страницTreatment For Eating DisordersPsihoterapeut Alina VranăuОценок пока нет

- Sergei Soloviov - Jose Raul Capablanca Games 1901-1924 (Chess Stars 2004) - EditableДокумент368 страницSergei Soloviov - Jose Raul Capablanca Games 1901-1924 (Chess Stars 2004) - EditableHernanArrondoОценок пока нет

- Technical Analysis CourseДокумент51 страницаTechnical Analysis CourseAkshay Chordiya100% (1)

- Indian Banking - Sector Report - 15-07-2021 - SystematixДокумент153 страницыIndian Banking - Sector Report - 15-07-2021 - SystematixDebjit AdakОценок пока нет

- Intensive Care Fundamentals: František Duška Mo Al-Haddad Maurizio Cecconi EditorsДокумент278 страницIntensive Care Fundamentals: František Duška Mo Al-Haddad Maurizio Cecconi EditorsthegridfanОценок пока нет

- Short-Term Memory and Working MemoryДокумент32 страницыShort-Term Memory and Working Memorysiempreviva84Оценок пока нет

- DBT For PTSD Related To Childhood Sexual AbuseДокумент5 страницDBT For PTSD Related To Childhood Sexual Abusecameronanddianne3785Оценок пока нет

- Grade 10 - SharmajiДокумент8 страницGrade 10 - Sharmajijuned ansariОценок пока нет

- EMDR Therapy of Panic Disorder and AgoraphobiaДокумент11 страницEMDR Therapy of Panic Disorder and AgoraphobiaMarta Llave AguileraОценок пока нет

- Hard Rock Miner - S Handbook - Jack de La Vergne - Edition 3 - 2003Документ330 страницHard Rock Miner - S Handbook - Jack de La Vergne - Edition 3 - 2003Adriel senciaОценок пока нет

- Polymer ConcreteДокумент15 страницPolymer ConcreteHew LockОценок пока нет

- Intensive Short Term Dynamic Psychotherapy For GeneralizedДокумент10 страницIntensive Short Term Dynamic Psychotherapy For GeneralizedNéstor X. PortalatínОценок пока нет

- Top German AcesДокумент24 страницыTop German AcesKlaus Richter100% (1)

- INECO Desregulación-Emocional Clase3 Stepps PDFДокумент12 страницINECO Desregulación-Emocional Clase3 Stepps PDFAgus BlancoОценок пока нет

- John F. Clarkin Et Alia (2007) - Evaluating Three Treatments For Bordeline Personality Disorder A Multiwave StudyДокумент7 страницJohn F. Clarkin Et Alia (2007) - Evaluating Three Treatments For Bordeline Personality Disorder A Multiwave StudyDaniel MaldonadoОценок пока нет

- Geront/gnu 018Документ10 страницGeront/gnu 018Cristina MPОценок пока нет

- Prediction of Treatment Discontinuation and Recovery From Borderline Personality DisorderДокумент12 страницPrediction of Treatment Discontinuation and Recovery From Borderline Personality DisorderDaniela Saralegui FОценок пока нет

- Bradley Et Al. (2006)Документ14 страницBradley Et Al. (2006)jehonol883Оценок пока нет

- Linehan 1991Документ5 страницLinehan 1991Ekatterina DavilaОценок пока нет

- Beneficios Terapia BuenaДокумент1 страницаBeneficios Terapia BuenaCristina MPОценок пока нет

- Metaanalisis CBT Vs TauДокумент14 страницMetaanalisis CBT Vs TauIndrawaty SuhuyanliОценок пока нет

- Stephan Doering Et Alia (2010) - Transference-Focused Psychotherapy v. Treatment by Comunity Psychotherapist For BPDДокумент9 страницStephan Doering Et Alia (2010) - Transference-Focused Psychotherapy v. Treatment by Comunity Psychotherapist For BPDDaniel MaldonadoОценок пока нет

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy Compared With General Psychiatric Management For Borderline Personality Disorder Clinical Outcomes and Functioning Over A 2-Year Follow-UpДокумент12 страницDialectical Behavior Therapy Compared With General Psychiatric Management For Borderline Personality Disorder Clinical Outcomes and Functioning Over A 2-Year Follow-UpPechopalomo 90Оценок пока нет

- McEvoy 2015 MCT Group For GADДокумент9 страницMcEvoy 2015 MCT Group For GADmarggiОценок пока нет

- Comparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderДокумент8 страницComparison of Clinical Significance of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy For Major Depressive DisorderAnanda Amanda cintaОценок пока нет

- Cognitive Enhancement Therapy For SchizophreniaДокумент11 страницCognitive Enhancement Therapy For SchizophreniaPsikiatri 76 UndipОценок пока нет

- NIH Public AccessДокумент31 страницаNIH Public AccessLuciana MarinОценок пока нет

- Changes in Neuropsychological Functioning Following Treatment For Late-Life Generalised Anxiety DisorderДокумент9 страницChanges in Neuropsychological Functioning Following Treatment For Late-Life Generalised Anxiety DisorderAnais UrdanetaОценок пока нет

- Kroenke2007 GAD7Документ10 страницKroenke2007 GAD7Imam AbidinОценок пока нет

- Behavior TherapyДокумент29 страницBehavior TherapyKrisztina MkОценок пока нет

- Cognitive-Behavioraltherapy Fordepression in Parkinson'Sdisease:A Randomized, Controlled TrialДокумент9 страницCognitive-Behavioraltherapy Fordepression in Parkinson'Sdisease:A Randomized, Controlled TrialAleja ToPaОценок пока нет

- Velligan Et Al 2000 Randomized Controlled Trial of The Use of Compensatory Strategies To Enhance Adaptive FunctioningДокумент7 страницVelligan Et Al 2000 Randomized Controlled Trial of The Use of Compensatory Strategies To Enhance Adaptive FunctioningKaterina ChatzОценок пока нет

- Boston Medical and Surgical Journal Volume 359 Issue 26 2008 (Doi 10.1056/nejmoa0804633) Walkup, John T. Albano, Anne Marie Piacentini, John Birmaher, - Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, SertralineДокумент14 страницBoston Medical and Surgical Journal Volume 359 Issue 26 2008 (Doi 10.1056/nejmoa0804633) Walkup, John T. Albano, Anne Marie Piacentini, John Birmaher, - Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, SertralineKharisma FatwasariОценок пока нет

- DBT Vs CBT On Emotion Regulation and Minfduness in Patients With Generalized Anxiety DisorderДокумент8 страницDBT Vs CBT On Emotion Regulation and Minfduness in Patients With Generalized Anxiety DisorderRAQUEL MENDOZA LOPEZОценок пока нет

- The Choice Point Model of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy With Inpatient Substance Use and Co-Occurring PopulationsДокумент14 страницThe Choice Point Model of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy With Inpatient Substance Use and Co-Occurring PopulationsGustavo PaniaguaОценок пока нет

- Management of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Atypical AntipsychoticsДокумент17 страницManagement of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Atypical Antipsychoticsnithiphat.tОценок пока нет

- Anxiety Disorders in Primary CareДокумент10 страницAnxiety Disorders in Primary CareJuan Carlos LrОценок пока нет

- Tugas 1Документ10 страницTugas 1Siti QomariaОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Anxiety Disorders by Psychiatrists From The American Psychiatric Practice Research NetworkДокумент6 страницTreatment of Anxiety Disorders by Psychiatrists From The American Psychiatric Practice Research NetworkStephОценок пока нет

- Depressão e Atividade FisicaДокумент8 страницDepressão e Atividade FisicaAdriana DavoglioОценок пока нет

- (2009) Mazzucchelli, Kane and Ress. BA Treatments For Depression in Adults A Meta Analysis and ReviewДокумент29 страниц(2009) Mazzucchelli, Kane and Ress. BA Treatments For Depression in Adults A Meta Analysis and ReviewJoão Gabriel Ferreira ArgondizziОценок пока нет

- Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For CHДокумент13 страницTrauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For CHLuis BernardoОценок пока нет

- Exercise and AnxietyДокумент11 страницExercise and AnxietyPelina LazariОценок пока нет

- Rou Saud 2007Документ11 страницRou Saud 2007healliz36912Оценок пока нет

- Integrative ReviewДокумент15 страницIntegrative Reviewapi-433917537Оценок пока нет

- (Stanley) Joc90025 - 1460 - 1467Документ8 страниц(Stanley) Joc90025 - 1460 - 1467niia kurniiasihОценок пока нет

- The Treatment For Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) : Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety OutcomesДокумент14 страницThe Treatment For Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) : Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety OutcomesioanaОценок пока нет

- We Therell 2009Документ10 страницWe Therell 2009Oslo SaputraОценок пока нет

- Mehlum Et Al., 2014Документ10 страницMehlum Et Al., 2014jesusОценок пока нет

- JURNAL 2 Augmentation Strategies For Treatment-Resistant Anxiety Disorders A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis-dikonversiДокумент15 страницJURNAL 2 Augmentation Strategies For Treatment-Resistant Anxiety Disorders A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis-dikonversiNixal KurniawanОценок пока нет

- The Promise of Symptom-Targeted Intervention To Manage Depression in Dialysis PatientsДокумент8 страницThe Promise of Symptom-Targeted Intervention To Manage Depression in Dialysis Patientsmelissa dannyОценок пока нет

- Meta-Analysis of The Efficacy of Treatments For PTSDДокумент10 страницMeta-Analysis of The Efficacy of Treatments For PTSDJulianaОценок пока нет

- Description CBT To Adhd AdultsДокумент17 страницDescription CBT To Adhd AdultsryanqiuyОценок пока нет

- Terapias No Farmacológicas de Tratamiento Del Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático en Emergencistas Revisión de AlcanceДокумент11 страницTerapias No Farmacológicas de Tratamiento Del Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático en Emergencistas Revisión de AlcanceMelissaОценок пока нет

- Practice Parameter: Management of Dementia (An Evidence-Based Review)Документ13 страницPractice Parameter: Management of Dementia (An Evidence-Based Review)Jeni JimОценок пока нет

- Psychosocial Treatments For Bipolar Depression A 1-Year Randomized Trial From The Systematic Treatment Enhanced Program PDFДокумент9 страницPsychosocial Treatments For Bipolar Depression A 1-Year Randomized Trial From The Systematic Treatment Enhanced Program PDFMichael Spike LevinОценок пока нет

- Benefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseДокумент6 страницBenefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseLaura Alvarez AbenzaОценок пока нет

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptДокумент17 страницNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptjindgi23Оценок пока нет

- Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamental em Grupo No TOC Ensaio Randomizado Cordioli 2003Документ6 страницTerapia Cognitivo-Comportamental em Grupo No TOC Ensaio Randomizado Cordioli 2003Hocus PocusОценок пока нет

- Mentalization-Based Treatment For Self-Harm in Adolescents - A Randomized Controlled TrialДокумент13 страницMentalization-Based Treatment For Self-Harm in Adolescents - A Randomized Controlled TrialManya DhuparОценок пока нет

- Art Taa3Документ5 страницArt Taa3CristinaОценок пока нет

- Evaluating Three Treatments For Borderline Personality Disorder: A Multiwave StudyДокумент7 страницEvaluating Three Treatments For Borderline Personality Disorder: A Multiwave StudyPamela Cortés PeñaОценок пока нет

- 10 1016@j Jocn 2018 10 042Документ11 страниц10 1016@j Jocn 2018 10 042RavennaОценок пока нет

- Dolan 1996Документ7 страницDolan 1996Ainia TaufiqaОценок пока нет

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofДокумент12 страницNew England Journal Medicine: The ofwardahОценок пока нет

- PP + CBTДокумент8 страницPP + CBTLev FyodorОценок пока нет

- Efficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological Treat-Ments For Depressive Disorders in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Network Meta-AnalysisДокумент11 страницEfficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological Treat-Ments For Depressive Disorders in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Network Meta-AnalysisPutri YingОценок пока нет

- Research 3Документ12 страницResearch 3Pratxxm PatelОценок пока нет

- Psychological Approaches to Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Clinician's Guide to Assessment and TreatmentОт EverandPsychological Approaches to Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Clinician's Guide to Assessment and TreatmentОценок пока нет

- Drug Use and Abuse in Sport Ver CocainaДокумент37 страницDrug Use and Abuse in Sport Ver CocainaAaser AasdeОценок пока нет

- Tribunal Arbitral Du Sport Court of Arbitration For SportДокумент19 страницTribunal Arbitral Du Sport Court of Arbitration For SportAaser AasdeОценок пока нет

- Schizophrenia Research: Gordon L.F. Cheng, Joey C.Y. Tang, Frendi W.S. Li, Esther Y.Y. Lau, Tatia M.C. LeeДокумент6 страницSchizophrenia Research: Gordon L.F. Cheng, Joey C.Y. Tang, Frendi W.S. Li, Esther Y.Y. Lau, Tatia M.C. LeeAaser AasdeОценок пока нет

- Renner 2005Документ11 страницRenner 2005Aaser AasdeОценок пока нет

- Drug and Alcohol DependenceДокумент8 страницDrug and Alcohol DependenceAaser AasdeОценок пока нет

- Forum Discussion #7 UtilitarianismДокумент3 страницыForum Discussion #7 UtilitarianismLisel SalibioОценок пока нет

- Carr v. NH State Prison, Warden - Document No. 2Документ5 страницCarr v. NH State Prison, Warden - Document No. 2Justia.comОценок пока нет

- Communique Supply Teacher (Oriental Languages) (Primary) 2021-2022Документ4 страницыCommunique Supply Teacher (Oriental Languages) (Primary) 2021-2022nishiОценок пока нет

- Rostam and SohrabДокумент16 страницRostam and Sohrabronnel100% (1)

- A Descriptive-Comparative StudyДокумент32 страницыA Descriptive-Comparative StudyJanelle DionisioОценок пока нет

- Grade Up CurrentsДокумент273 страницыGrade Up CurrentsAmiya RoyОценок пока нет

- DRTA-directed Reading Thinking Activity: M. Truscott Staff Development 9-24-10Документ13 страницDRTA-directed Reading Thinking Activity: M. Truscott Staff Development 9-24-10ehaines24Оценок пока нет

- Cambridge IGCSE: PHYSICS 0625/63Документ16 страницCambridge IGCSE: PHYSICS 0625/63...Оценок пока нет

- Lee Meisel 2002 Adsorption and Surface Enhanced Raman of Dyes On Silver and Gold SolsДокумент5 страницLee Meisel 2002 Adsorption and Surface Enhanced Raman of Dyes On Silver and Gold SolsGabriel FernandesОценок пока нет

- Silent Reading With Graph1Документ2 страницыSilent Reading With Graph1JonaldSamueldaJoseОценок пока нет

- Industrial Thread (Sewing Thread)Документ8 страницIndustrial Thread (Sewing Thread)sandhyaishtaОценок пока нет

- FOR of Tution Fee: Application ReimbursementДокумент1 страницаFOR of Tution Fee: Application ReimbursementBhavithavОценок пока нет

- 2014 Price ListДокумент17 страниц2014 Price ListMartin J.Оценок пока нет

- Further Investigations of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehy PDFДокумент7 страницFurther Investigations of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehy PDFrabin1994Оценок пока нет

- Preview ISO+15613-2004Документ6 страницPreview ISO+15613-2004Brijith0% (1)

- Entrep 1st PerioДокумент5 страницEntrep 1st PerioMargarette FajardoОценок пока нет

- Applied Chemistry-IДокумент16 страницApplied Chemistry-Islm.sbipОценок пока нет

- Working Capital Management by Birla GroupДокумент39 страницWorking Capital Management by Birla GroupHajra ShahОценок пока нет

- Best Neurologist in BangaloreДокумент3 страницыBest Neurologist in BangaloreAlgoTrends AlgoTrendsОценок пока нет