Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Experimental Research

Загружено:

Rohanpawer PawarАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Experimental Research

Загружено:

Rohanpawer PawarАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Experimental Research

The major feature that distinguishes experimental research from other types of research is

that the researcher manipulates the independent variable. There are a number

of experimental group designs in experimental research. Some of these qualify as

experimental research, others do not.

In true experimental research, the researcher not only manipulates the

independent variable, he or she also randomly assigned individuals to the various

treatment categories (i.e., control and treatment).

In quasi experimental research, the researcher does not randomly assign subjects

to treatment and control groups. In other words, the treatment is not distributed

among participants randomly. In some cases, a researcher may randomly assigns

one whole group to treatment and one whole group to control. In this case, quasi-

experimental research involves using intact groups in an experiment, rather than

assigning individuals at random to research conditions. (some researchers define

this latter situation differently. For our course, we will allow this definition).

In causal comparative (ex post facto) research, the groups are already formed. It

does not meet the standards of an experiment because the independent variable in

not manipulated.

The statistics by themselves have no meaning. They only take on meaning within the

design of your study. If we just examine stats, bread can be deadly.

The term validity is used three ways in research…

1. In the sampling unit, we learn about external validity (generalizability).

2. In the survey unit, we learn about instrument validity.

3. In this unit, we learn about internal validity and external validity. Internal

validity means that the differences that we were found between groups on the

dependent variable in an experiment were directly related to what the researcher

did to the independent variable, and not due to some other unintended variable

(confounding variable). Simply stated, the question addressed by internal validity

is “Was the study done well?” Once the researcher is satisfied that the study was

done well and the independent variable caused the dependent variable (internal

validity), then the research examines external validity (under what conditions

[ecological] and with whom [population] can these results be replicated [Will I get

the same results with a different group of people or under different

circumstances?]). If a study is not internally valid, then considering external

validity is a moot point (If the independent did not cause the dependent, then there

is no point in applying the results [generalizing the results] to other situations.).

Interestingly, as one tightens a study to control for treats to internal validity, one

decreases the generalizability of the study (to whom and under what conditions

one can generalize the results).

There are several common threats to internal validity in experimental research. They are

described in our text. I have review each below (this material is also included in

the PowerPoint Presentation on Experimental Research for this unit):

Subject Characteristics (Selection Bias/Differential Selection) — The groups

may have been different from the start. If you were testing instructional strategies

to improve reading and one group enjoyed reading more than the other group, they

may improve more in their reading because they enjoy it, rather than the

instructional strategy you used.

Loss of Subjects (Mortality) — All of the high or low scoring subject may have

dropped out or were missing from one of the groups. If we collected posttest data

on a day when the honor society was on field trip at the treatment school, the mean

for the treatment group would probably be much lower than it really should have

been.

Location — Perhaps one group was at a disadvantage because of their

location. The city may have been demolishing a building next to one of the

schools in our study and there are constant distractions which interferes with our

treatment.

Instrumentation Instrument Decay — The testing instruments may not be

scores similarly. Perhaps the person grading the posttest is fatigued and pays less

attention to the last set of papers reviewed. It may be that those papers are from

one of our groups and will received different scores than the earlier group’s papers

Data Collector Characteristics — The subjects of one group may react

differently to the data collector than the other group. A male interviewing males

and females about their attitudes toward a type of math instruction may not receive

the same responses from females as a female interviewing females would.

Data Collector Bias — The person collecting data my favors one group, or some

characteristic some subject possess, over another. A principal who favors strict

classroom management may rate students’ attention under different teaching

conditions with a bias toward one of the teaching conditions.

Testing — The act of taking a pretest or posttest may influence the results of the

experiment. Suppose we were conducting a unit to increase student sensitivity to

prejudice. As a pretest we have the control and treatment groups watch Shindler’s

List and write a reaction essay. The pretest may have actually increased both

groups’ sensitivity and we find that our treatment groups didn’t score any higher

on a posttest given later than the control group did. If we hadn’t given the pretest,

we might have seen differences in the groups at the end of the study.

History — Something may happen at one site during our study that influences the

results. Perhaps a classmate dies in a car accident at the control site for a study

teaching children bike safety. The control group may actually demonstrate more

concern about bike safety than the treatment group.

Maturation –There may be natural changes in the subjects that can account for

the changes found in a study. A critical thinking unit may appear more effective if

it taught during a time when children are developing abstract reasoning.

Hawthorne Effect — The subjects may respond differently just because they are

being studied. The name comes from a classic study in which researchers were

studying the effect of lighting on worker productivity. As the intensity of the

factor lights increased, so did the work productivity. One researcher suggested that

they reverse the treatment and lower the lights. The productivity of the workers

continued to increase. It appears that being observed by the researchers was

increasing productivity, not the intensity of the lights.

John Henry Effect — One group may view that it is competition with the other

group and may work harder than than they would under normal circumstances.

This generally is applied to the control group “taking on” the treatment group. The

terms refers to the classic story of John Henry laying railroad track.

Resentful Demoralization of the Control Group — The control group may

become discouraged because it is not receiving the special attention that is given

to the treatment group. They may perform lower than usual because of this.

Regression (Statistical Regression) — A class that scores particularly low can be

expected to score slightly higher just by chance. Likewise, a class that scores

particularly high, will have a tendency to score slightly lower by chance. The

change in these scores may have nothing to do with the treatment.

Implementation –The treatment may not be implemented as intended. A study

where teachers are asked to use student modeling techniques may not show

positive results, not because modeling techniques don’t work, but because the

teacher didn’t implement them or didn’t implement them as they were designed.

Compensatory Equalization of Treatment — Someone may feel sorry for the

control group because they are not receiving much attention and give them special

treatment. For example, a researcher could be studying the effect of laptop

computers on students’ attitudes toward math. The teacher feels sorry for the class

that doesn’t have computers and sponsors a popcorn party during math class. The

control group begins to develop a more positive attitude about mathematics.

Experimental Treatment Diffusion — Sometimes the control group actually

implements the treatment. If two different techniques are being tested in two

different third grades in the same building, the teachers may share what they are

doing. Unconsciously, the control may use of the techniques she or he learned

from the treatment teacher.

When planning a study, it is important to consider the threats to interval validity as we

finalize the study design. After we complete our study, we should reconsider each of the

threats to internal validity as we review our data and draw conclusions.

Conclusion:

Considering the above, it is now to time to explore an example of experimental research

using those concepts. Let’s say that a researcher wanted to investigate the effects of

using flipped classroom teaching techniques in an American history course. The

hypothesis being tested is that the flipped classroom teaching style will result in higher

test scores among the students. The researcher will begin by randomly assigning students

into two different sections of the course. The first section will be taught using the

traditional lecture format. The second section will be taught used flipped classroom

teaching techniques. The learning objectives and content for both sections will be

identical. Both sections will be given identical exams throughout the semester and the

scores between the two sections will be compared to assess student learning. The flipped

classroom teaching style is the independent variable. The dependent variable is the test

scores. The experimental group is the section of the course where the flipped classroom

technique is being used and the control group is the section that continues to utilize the

traditional lecture format. This is a classic example of the use of experimental research

design. The following modules will delve deeper into various aspects of experimental

research

Reference:

Bernard, H. R., & Bernard, H. R. (2012). Social research methods: Qualitative and

quantitative approaches. Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed

methods approaches. Sage publications.

Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., & Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational research: An

introduction . Longman Publishing.

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (1993). How to design and evaluate

research in education (Vol. 7). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Keppel, G. (1991). Design and analysis: A researcher's handbook . Prentice-Hall,

Inc.

Lipsey, M. W. (1990). Design sensitivity: Statistical power for experimental

research (Vol. 19). Sage.

Neuman, W. L., & Neuman, W. L. (2006). Social research methods: Qualitative

and quantitative approaches.

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative

approaches. Sage.

Вам также может понравиться

- Types of Research Experimental Group DesignsДокумент15 страницTypes of Research Experimental Group DesignsChristian Catherine Laderas GonzaloОценок пока нет

- Experimental ResearchДокумент30 страницExperimental Researchharis budianaОценок пока нет

- Course ONE: Experimental ResearchДокумент17 страницCourse ONE: Experimental Researchliss missОценок пока нет

- 21.cpsy.34 Research MethodsДокумент14 страниц21.cpsy.34 Research MethodsVictor YanafОценок пока нет

- Types of Experiments Research DesignsДокумент30 страницTypes of Experiments Research DesignsNIkolai CastilloОценок пока нет

- Threats To ValidityДокумент5 страницThreats To ValidityAbhijeet DandageОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2Документ54 страницыChapter 2marg de jesusОценок пока нет

- Experimental ResearchДокумент7 страницExperimental Research0044 Muhammad Cikal HanafiОценок пока нет

- 1-2 PR2 Nature and Inquiry of Quantitative Research, Writes A Research TitleДокумент8 страниц1-2 PR2 Nature and Inquiry of Quantitative Research, Writes A Research TitleAngeline SiaОценок пока нет

- Phenomenology: Philosophy Husserl HeideggerДокумент14 страницPhenomenology: Philosophy Husserl Heideggerlinda kumala dewiОценок пока нет

- Causal Comparative Research - FullДокумент38 страницCausal Comparative Research - FullTừ Quỳnh NhưОценок пока нет

- Be Nish 8604Документ19 страницBe Nish 8604Sehar SultanОценок пока нет

- Shs Eapp q2 Module Week6Документ6 страницShs Eapp q2 Module Week6Rhea Tecson-Saldivar CastilloОценок пока нет

- Threats To Internal and External ValidityДокумент44 страницыThreats To Internal and External Validitynasz_alia100% (2)

- Exploratory and Formal StudiesДокумент3 страницыExploratory and Formal StudiesKnt Nallasamy Gounder100% (2)

- Psy 103 Chapter 2Документ7 страницPsy 103 Chapter 2maeveflavourОценок пока нет

- Draws A Conclusion Control Group Control: Naturalistic Observation Is ObservationalДокумент6 страницDraws A Conclusion Control Group Control: Naturalistic Observation Is ObservationalBushra MumtazОценок пока нет

- Experimental ResearchДокумент38 страницExperimental ResearchSuvrhy MuhajjiОценок пока нет

- Exercises: Chapter 9 ReviewДокумент21 страницаExercises: Chapter 9 ReviewAlma Ganas ArdenioОценок пока нет

- Module and AS Template in Practical Research 2week 2Документ10 страницModule and AS Template in Practical Research 2week 2erica lamsenОценок пока нет

- Correlational Research DefinitionДокумент23 страницыCorrelational Research DefinitionDon DiazОценок пока нет

- Internal and External ValidationДокумент14 страницInternal and External ValidationXiel John BarnuevoОценок пока нет

- Materi Experimental ResearchДокумент7 страницMateri Experimental ResearchGabriel Klinton ManikОценок пока нет

- Causal Comparative ResearchДокумент24 страницыCausal Comparative ResearchJuniSiburianОценок пока нет

- Types of Research MethodsДокумент3 страницыTypes of Research Methodsapi-369936185% (13)

- Between Subjects DesignДокумент4 страницыBetween Subjects Designterezki100% (1)

- Chapter Four - Research Design and Sampling-1Документ42 страницыChapter Four - Research Design and Sampling-1Sitra AbduОценок пока нет

- Confounding Exercise - Research Methods (Psychology)Документ17 страницConfounding Exercise - Research Methods (Psychology)Nardira NugrohoОценок пока нет

- Assignment ON Advance Research Methods and Statistics in Education (M.ED./3/CC/302)Документ7 страницAssignment ON Advance Research Methods and Statistics in Education (M.ED./3/CC/302)KC.LalmumpuiiОценок пока нет

- EDD3101 GROUP 9em COURSEWORK 1Документ8 страницEDD3101 GROUP 9em COURSEWORK 1SadaticloОценок пока нет

- Research Project Physical Experiment: Submitted To: Mam Nadia Bakhtawer Course: Intro To Psychology Submitted By: Group 6Документ14 страницResearch Project Physical Experiment: Submitted To: Mam Nadia Bakhtawer Course: Intro To Psychology Submitted By: Group 6nad101Оценок пока нет

- Types of ResearchДокумент3 страницыTypes of ResearchMariz Natividad Gappe-RivasОценок пока нет

- Field Method in PsychДокумент16 страницField Method in PsychChin Dela CruzОценок пока нет

- Experimental Research 4Документ3 страницыExperimental Research 4Dendi DarmawanОценок пока нет

- Journal Club 4: Intervention StudiesДокумент4 страницыJournal Club 4: Intervention StudiesSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeОценок пока нет

- EbookДокумент8 страницEbookod armyОценок пока нет

- Abouot ResearchДокумент21 страницаAbouot ResearchJames Darrel LansanganОценок пока нет

- Chapter Two Revision: Exam Type QuestionДокумент7 страницChapter Two Revision: Exam Type QuestionNaeemaKraanОценок пока нет

- The Quantitative Research DesignДокумент30 страницThe Quantitative Research Designnv471646Оценок пока нет

- Research MethodsДокумент10 страницResearch MethodsphamhieniolОценок пока нет

- Capstone 2Документ3 страницыCapstone 2Ma.Dulce ManalastasОценок пока нет

- RESEARCHДокумент10 страницRESEARCHMarvel FabroОценок пока нет

- Research Methods 1Документ25 страницResearch Methods 1Timothy AkaasiОценок пока нет

- Experimental Psychology For BAДокумент14 страницExperimental Psychology For BAAAkancha SinghОценок пока нет

- Techniques Used in Studying Behaviour/Conduct Research in Educational PsychologyДокумент33 страницыTechniques Used in Studying Behaviour/Conduct Research in Educational PsychologyFatiha IsmadiОценок пока нет

- Activity Sheet in Research 9Q1W2finalДокумент6 страницActivity Sheet in Research 9Q1W2finalAsh AbanillaОценок пока нет

- Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad: Course Code: 8629Документ9 страницAllama Iqbal Open University Islamabad: Course Code: 8629Hamid ShahОценок пока нет

- Psychology NotesДокумент17 страницPsychology NotesBasira ZolmayОценок пока нет

- Choosing The Appropriate Research DesignДокумент49 страницChoosing The Appropriate Research DesignAngelito MayoОценок пока нет

- Identifying Threats To Internal Validity WorksheetДокумент2 страницыIdentifying Threats To Internal Validity Worksheetmark leeОценок пока нет

- Quantitative Reseearch Its Characteristics, Strengths & Weaknesses and KindsДокумент26 страницQuantitative Reseearch Its Characteristics, Strengths & Weaknesses and KindsIvy Luz100% (1)

- Pr2 HandoutДокумент6 страницPr2 HandoutShahanna GarciaОценок пока нет

- Basic Concepts in Research: Objective SДокумент6 страницBasic Concepts in Research: Objective Sbon jonard sayoОценок пока нет

- CHP 8 - Research - Methods - Part - IДокумент27 страницCHP 8 - Research - Methods - Part - Isinghyashwant102Оценок пока нет

- Assignment For Research Methodology Vop202 MyДокумент6 страницAssignment For Research Methodology Vop202 MyTirusew ChekolОценок пока нет

- Experimental Research DesignДокумент26 страницExperimental Research DesignAmitSolanki100% (1)

- Child and Adolescent Development: A NarrationДокумент6 страницChild and Adolescent Development: A NarrationLeowens VenturaОценок пока нет

- PR2 Week 6Документ10 страницPR2 Week 6Camille CornelioОценок пока нет

- English PaperДокумент8 страницEnglish PaperRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- MicroДокумент1 страницаMicroRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- SL - No Date Name of The Agency Time SingДокумент1 страницаSL - No Date Name of The Agency Time SingRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Front SheetДокумент1 страницаFront SheetRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- ABSTRACTДокумент1 страницаABSTRACTRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- HRDPPPДокумент4 страницыHRDPPPRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Application FormДокумент2 страницыApplication FormRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Exchange Board of India (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 1992 ( SEBIДокумент14 страницExchange Board of India (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations, 1992 ( SEBIRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Curriculum Vitae: DARSHAN E.J (Diploma in Agriculture)Документ3 страницыCurriculum Vitae: DARSHAN E.J (Diploma in Agriculture)Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Mass Wasting2Документ45 страницMass Wasting2Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- In Sid e R T Rad in G-An Alysin G T H e Ind Ian Persp Ect I Ve - Arjun Nihal SinghДокумент14 страницIn Sid e R T Rad in G-An Alysin G T H e Ind Ian Persp Ect I Ve - Arjun Nihal SinghRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Resume: Avesha N D/o Nagaraj Kanagalasara Umblebylu Post Shivamogga TQ and Dist Pin 577115 Phone No: 6360901109Документ2 страницыResume: Avesha N D/o Nagaraj Kanagalasara Umblebylu Post Shivamogga TQ and Dist Pin 577115 Phone No: 6360901109Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Curriculam VitaДокумент4 страницыCurriculam VitaRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Project 22Документ11 страницProject 22Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- SandeepДокумент7 страницSandeepRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Project 22Документ11 страницProject 22Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

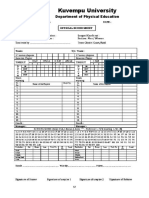

- Kuvempu University: Department of Physical EducationДокумент2 страницыKuvempu University: Department of Physical EducationRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Furnishing of Report of An AccountantДокумент2 страницыFurnishing of Report of An AccountantRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- (To Be Retained by The Bank) (To Be Sent by The Applicant To CSIR) (To Be Retained by The Applicant)Документ1 страница(To Be Retained by The Bank) (To Be Sent by The Applicant To CSIR) (To Be Retained by The Applicant)Pankaj GuptaОценок пока нет

- Project 22Документ3 страницыProject 22Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- ID CardДокумент1 страницаID CardRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- (To Be Retained by The Bank) (To Be Sent by The Applicant To CSIR) (To Be Retained by The Applicant)Документ1 страница(To Be Retained by The Bank) (To Be Sent by The Applicant To CSIR) (To Be Retained by The Applicant)Pankaj GuptaОценок пока нет

- University Grants Commission Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg NEW DELHI - 110002 Final Project Report From 1/7/2012 To 31/12/2015Документ2 страницыUniversity Grants Commission Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg NEW DELHI - 110002 Final Project Report From 1/7/2012 To 31/12/2015Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Certificate 1111Документ1 страницаCertificate 1111Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- CoverДокумент1 страницаCoverRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Unit - 2 Multimedia Building Blocks: Thontadari C., Dept. of B.C.A., S.M.R.F.G College 1Документ1 страницаUnit - 2 Multimedia Building Blocks: Thontadari C., Dept. of B.C.A., S.M.R.F.G College 1Rohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Soniya H. S.: ObjectiveДокумент2 страницыSoniya H. S.: ObjectiveRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- BorderДокумент1 страницаBorderRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Provogue: Gama' Is A Study in Leadership and Resourcefulness in Your Interest LaysДокумент2 страницыProvogue: Gama' Is A Study in Leadership and Resourcefulness in Your Interest LaysRohanpawer PawarОценок пока нет

- Excellence For All: ChildrenДокумент100 страницExcellence For All: ChildrenJulie Millard-EnglishОценок пока нет

- Punjabi AДокумент7 страницPunjabi AKaran GillОценок пока нет

- 6 DLL HOPE 3 2019-2020 JulyДокумент2 страницы6 DLL HOPE 3 2019-2020 JulyCelia BautistaОценок пока нет

- HRDДокумент62 страницыHRDTedwinThomasОценок пока нет

- Mini Lesson Plan 1Документ4 страницыMini Lesson Plan 1api-392426520Оценок пока нет

- Fields of NursingДокумент10 страницFields of NursingSj EclipseОценок пока нет

- AERO462 - Outline - F2020Документ8 страницAERO462 - Outline - F2020Navjot SinghОценок пока нет

- Minutes of The MeetingДокумент4 страницыMinutes of The MeetingRowella CatugasОценок пока нет

- Why English Should Be The Medium of InstructionДокумент3 страницыWhy English Should Be The Medium of InstructionLia CambangayОценок пока нет

- NAAC 10.12.1888888 NewДокумент48 страницNAAC 10.12.1888888 Newచిమ్ముల సందీప్ రెడ్డిОценок пока нет

- Title - An Indonesian Assignment Author - Bio - : Graham PatersonДокумент14 страницTitle - An Indonesian Assignment Author - Bio - : Graham PatersonGraham PatersonОценок пока нет

- Treatment Approaches in Management of StutteringДокумент46 страницTreatment Approaches in Management of StutteringKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHN100% (1)

- RBT 40 Hour Training Packet 201117Документ4 страницыRBT 40 Hour Training Packet 201117hp50% (2)

- Angela Graziano ResumeДокумент1 страницаAngela Graziano Resumeapi-314425210Оценок пока нет

- Prof Ed 5 Lesson 7 Preparing For Quality Teaching 20231022 003225 0000Документ17 страницProf Ed 5 Lesson 7 Preparing For Quality Teaching 20231022 003225 0000anniejill15Оценок пока нет

- Biotechnology Course Syllabus Form Bt.S020: Biology (Code: Bt155Iu)Документ10 страницBiotechnology Course Syllabus Form Bt.S020: Biology (Code: Bt155Iu)Quan ThieuОценок пока нет

- Wetsus Academy FolderДокумент4 страницыWetsus Academy FolderDavid ParionaОценок пока нет

- Tpack SamrДокумент17 страницTpack Samrapi-245872335Оценок пока нет

- Resume SidharthДокумент2 страницыResume SidharthSidharth SatpathyОценок пока нет

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review Form (Ipcrf)Документ12 страницIndividual Performance Commitment and Review Form (Ipcrf)Maggie JoloyohoyОценок пока нет

- Test Bank For Berry and Kohns Operating Room Technique 13th Edition by PhillipsДокумент3 страницыTest Bank For Berry and Kohns Operating Room Technique 13th Edition by Phillipsa522345415100% (3)

- Franklin Watts Downloadables For Every Child's Learning JourneyДокумент3 страницыFranklin Watts Downloadables For Every Child's Learning JourneyMarija GruncheskaОценок пока нет

- DEPED School FormsДокумент30 страницDEPED School FormsMayette ManigosОценок пока нет

- AccaДокумент15 страницAccaAvinash AcharyaОценок пока нет

- Template For Grades AnalysisДокумент11 страницTemplate For Grades AnalysisTarbz, MAEDОценок пока нет

- Guide Question Answer: Reflection Paper/Questionnaire TemplateДокумент2 страницыGuide Question Answer: Reflection Paper/Questionnaire TemplateJoris SulimaОценок пока нет

- Solid EdgeДокумент5 страницSolid EdgesumikannuОценок пока нет

- Using Tic Tac Toe Game To ImproveДокумент120 страницUsing Tic Tac Toe Game To ImproveDewa KagamineОценок пока нет

- Capstone Project ModuleДокумент12 страницCapstone Project ModuleJeffrey MasicapОценок пока нет

- Dr. Wolf and The "Ancient Roots": Neoshamanism in SerbiaДокумент20 страницDr. Wolf and The "Ancient Roots": Neoshamanism in SerbiaNoel PutnikОценок пока нет