Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Admission of Term Infants To The Nicu

Загружено:

carlsonrenovatioОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Admission of Term Infants To The Nicu

Загружено:

carlsonrenovatioАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

original article

Admission of term infants to the neonatal

intensive care unit in a Saudi tertiary

teaching hospital: cumulative incidence and

risk factors

Heidi Al-Wassia, Mafaza Saber

From the Department of Pediatrics, King Abdulaziz University Faculty of Medicine, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Dr. Heidi Al-Wassia ∙ Department of Pediatrics, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 80215, Saudi Arabia ∙ T: +966-12-

6401000, ext 20208 ∙ halwassia@kau.edu.sa ∙ http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8208-4986

Ann Saudi Med 2017; 37(6): 420-424

DOI: 10.5144/0256-4947.2017.420

BACKGROUND: An increasing number of term infants of appropriate birthweight receive care in neonatal

intensive care units (NICUs).

OBJECTIVES: This study assessed the prevalence, patterns, and risk factors for admission of term infants to

a NICU to identify areas for quality improvement.

DESIGN: Cross-sectional analytical study.

SETTING: An academic and referral center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: The cases were all term infants (≥37 weeks gestational age) admitted to the

NICU between 1 January and 31 December 2015. The controls were term infants who were not admitted

to the NICU. Cases and controls were matched in a 1:1 ratio according to the date of birth (within one day).

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Prevalence, pattern, and risk factors for admission of term infants to the

NICU.

RESULTS: The rate of admission of term infants to the NICU during the study period was 4.1% (142 of 3314

live births in that year). Respiratory complications accounted for 36.6% (52/142) of admissions, followed by

hypoglycemia (23/142, 16.2%) and jaundice (11/142, 7.7%). Premature membrane rupture and non-Saudi

national status were the risk factors that remained significant after adjusting for confounders.

CONCLUSION: A growing number of term infants are admitted unexpectedly to the NICU. The risk factors

and pattern of admission of term infants to the NICU should receive more attention in quality improvement

and management agendas.

LIMITATIONS: This was a single-center study with limited access to information about unbooked mothers

and details of the hospital stay of the admitted neonates.

N

eonatal intensive care units (NICUs) provide age. Similarly, older audits undertaken in the United

life support to newborns; however, admis- Kingdom7 and Ireland8 have shown that the admission

sion to an NICU entails risks for both fami- of full-term neonates with ≥2500 gram (g) birthweight

lies and their admitted infants, including high costs.1,2 is not an infrequent event. The risk factors associated

Admission to the NICU interrupts the mother-infant with increased odds of admission of term infants to

bonding and establishment of breastfeeding.3-5 In an the NICU include the operative method of birth,9 elec-

epidemiologic time trend-analysis in of 38 units in the tive delivery before 39 weeks either vaginally or by ce-

United States between 2007 and 2012, the overall sarean section,10 maternal diabetes and hypertension,

admission rate increased by 23% after adjusting for ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status.11

maternal and neonatal characteristics.6 In the same co- The early identification of risk factors, with ensuing

hort, the admitted neonates were increasingly likely to synchronized interventions, may contribute to modify-

be full-term and of appropriate weight for gestational ing the effects associated with the admission of term

420 ANN SAUDI MED 2017 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER WWW.ANNSAUDIMED.NET

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT IN NICU original article

infants to the NICU. charts. Small for gestational age was defined as infants

To our knowledge, no previous national studies below the 10th centile for birthweight.13 Respiratory

have examined the patterns and risk factors of the distress requiring admission to the NICU was defined

admission of term infants to NICUs. In the face of na- by signs of labored breathing that required respiratory

tional and international neonatal bed crises, we be- support using oxygen or non-invasive or invasive ven-

lieve that it is crucial to evaluate this. Our objective tilation. Hypoglycemia was defined as blood glucose

was to ascertain the prevalence, describe the pattern, less than 2.6 mmol/L measured after two hours of life

and examine the risk factors for the admission of term that did not improve with feeding and which required

infants to the NICU at King Abdulaziz University (KAU) intravenous glucose infusion.14 Hypoxic-ischemic en-

Hospital between 1 January and 31 December 2015, cephalopathy was defined according to the American

in order to identify central areas to focus on for quality Academy of Pediatrics and American College of

improvement strategies. Obstetrics and Gynecology criteria that mandate the

use of hypothermia for management.15,16 Perinatal

PATIENTS AND METHODS depression was defined as the need for resuscitation

A retrospective chart review was performed to deter- beyond gentle stimulation, but did not fulfill the cri-

mine the prevalence and pattern of the admission of teria for the diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic encepha-

full-term neonates to the NICU. We also conducted lopathy. The unit of biomedical ethics at KAU Hospital

a case-control study to determine the risk factors as- approved the study.

sociated with the admission of full-term neonates to IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM

the NICU. The cases were full-term infants born and Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical anal-

admitted to the NICU at KAU Hospital. We randomly ysis. The prevalence of admission was calculated by

selected controls from all full-term infants who were dividing the number of term live births admitted to

not admitted to the NICU. Cases and controls were the NICU during the year assigned for data collection

matched in a 1:1 ratio according to the date of birth by the total number of term live births born in that

(within one day). The NICU at KAU Hospital contains year in KAU Hospital. The continuous variables were

36 beds and is a level III unit and referral center in the compared using the t-test and Mann-Whitney U tests

western region of Saudi Arabia, with approximately for normal and skewed data distributions, respectively.

350-400 admissions per year. Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categori-

All term infants (≥37 weeks gestation age) admit- cal variables between groups. In a multivariate logistic

ted to the NICU at KAU Hospital between 1 January regression, NICU admission was the dependent vari-

and 31 December 2015 were eligible for inclusion. able. Variables that were significant in the univariate

The gestational age was determined according to the analysis, and which may have differed between the

first day of last menstrual period if known or/and first- groups, were used as independent variables in the

trimester ultrasound.12 There were no exclusion criteria multivariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression

for participation in this study. The admission book of was used to determine potential risk factors for admis-

the NICU and the nursery’s admission records were re- sion of term infants to the NICU. P values <.05 were

viewed to determine the admission rate. The hospital considered statistically significant.

records of the admitted and nonadmitted infants were

reviewed to determine the reasons for admission and RESULTS

the risk factors associated with an increased odds of Of 3314 full-term infants were born at KAU Hospital

admission. The collected data included maternal age, between 1 January and 31 December 2015, 142 were

nationality, parity, history of diabetes or hypertension, admitted to the NICU, for a cumulative incidence of

premature rupture of membrane (PROM) before 37 4.1% (142/3314). Only 16% of the term infant admis-

weeks of gestation, mode of delivery, and whether sions were expected (23/142) (Table 1). There were

the delivery was spontaneous or elective. We also no significant differences in maternal age, parity, and

collected information from maternal charts about any body mass index between groups. Furthermore, the

associated pregnancy complications or fetal anoma- rates of hypertension, use of assisted reproductive

lies for which postnatal admission to the NICU was technology, and multiple pregnancies were compa-

expected. Unbooked mothers were those who did not rable between groups. Infants admitted to the NICU

attend the prenatal clinic in the hospital or any other were more often the children of non- Saudi national

healthcare facility. The reasons for admission were (P=.001) and unbooked mothers (P<.001). The moth-

determined from the admission notes in the infants’ ers of infants admitted to the NICU had a significantly

ANN SAUDI MED 2017 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER WWW.ANNSAUDIMED.NET 421

original article QUALITY IMPROVEMENT IN NICU

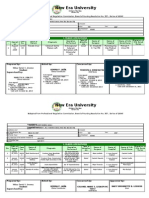

Table 1. Maternal and Infants demographic and clinical characteristics. significant correlation between non-national and un-

booked mothers (r=1, P<.001); therefore, only non-na-

Maternal characteristics Cases Controls

P value tional status was used in the regression model in order

Variable n=142 n=142

to avoid multicollinearity. When we adjusted for vari-

Maternal age (years), ables that differed statistically between the two groups,

30.5 (6.1) 29.6 (6.4) .78

mean (SD) only non-national status and patients presenting with

Non-national 60 (42.2) 33 (23.2) .001 PROM remained statistically significant (Table 3).

Unbooked 32 (22.5) 0 (0) <.001

DISCUSSION

Body mass index (mg/kg ) 2

29.4(7.5) 28.4 (5.9) .51 In the present study, the prevalence of admission of

Parity >2 73 (51.4) 76 (53.5) .72 term infants to the NICU was 4.1%, less than that re-

ported in other units.9,17-20 Only 16% of those admis-

Diabetes 36 (25.4) 19 (13.4) .01

sions were expected, similar to that reported previ-

Hypertension 7 (4.9) 6 (4.2) .78 ously.21 Admission of term or normal birthweight in-

Preeclampsia 3 (2.1) 4(2.8) .70 fants can be considered as low risk; however, several

studies have reported the opposite.6,18 In a popula-

Premature rupture of

9 (6.3) 1(0.7) .01 tion-based study of infants born to residents of 38

membrane

US states, approximately half of all NICU admissions

Chorioamnionitis 2 (1.4) 0 (0.0) .16

were for infants born ≥37 weeks of gestational age

Assisted reproductive and/or of normal weight even after adjusting for con-

4 (2.8) 2 (1.4) .41

technology

founders.6

Multiple pregnancy 3 (2.1) 0 (0.0) .13 In our study, PROM occurred significantly more fre-

Induced labor 79 (55.6) 47 (33.1) <.001 quently in mothers of infants admitted to the NICU

compared to the frequency among the infants who

Cesarean section 76 (53.5) 43 (30.3) <.001

were not admitted. The risk of PROM persisted after

Elective cesarean section 33 (23.2) 19 (13.4) .03 adjusting for confounders. This finding is in agree-

Expected admission 23 (16.2) 0 (0) <.001 ment with previous studies.19,22 Similar to previ-

ous studies, the mothers of infants admitted to the

Born outside the hospital 1 (0.7) 0 (0) .32

NICU had a higher rate of elective cesarean sections.

Infant characteristics Delivery after cesarean section is a risk factor for the

Birth weight (g), mean (SD) 2876 (693) 3033 (458) <.001 admission of term infants.9,17,23 However, the effect of

cesarean section as a risk factor for NICU admission

Male 88 (62) 74 (52.1) .09

in our study disappeared after adjusting for other risk

Small for gestational age 36 (25.4) 22 (15.5) .04 factors.

Apgar score at 1 min, Non-Saudi national mothers were mostly un-

8 (6,9) 9 (8,9) <.001

median (IQR) booked mothers; their infants constituted more than

half of those admitted to the NICU. KAU Hospital is

Apgar score at 5 min,

9 (8,10) 10 (9,10) <.001 a public hospital and mothers present to the hospital

median (IQR)

at the time of delivery for financial reasons. We had

Values are n (%) unless noted otherwise. Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation

limited information about the pregnancy of the un-

booked mothers; however, this risk factor remained

higher rate of diabetes (P=.01), PROM (P=.01) cesar- significant after controlling for other confounders.

ean delivery (P<.001) and induction of labor (P<.001). Low socioeconomic status is an independent risk

Fourteen of the 32 unbooked mothers underwent ce- factor for NICU admission.24 Unbooked mothers are

sarean delivery (43.8%). Infants admitted to the NICU reportedly of lower socioeconomic status and are

had a significantly lower birthweight and more were considered to have higher risks of pregnancy com-

small for gestational age. The reasons for the admis- plications including pre-eclampsia, postpartum hem-

sion of term infants to the NICU are depicted in Table orrhage, uterine rupture, and mortality compared to

2. Respiratory distress was most common, with a fre- booked mothers.25 Moreover, in our study and consis-

quency of 36.6% (52/142) of all admitted term infants, tent with other studies, there was a high rate of un-

followed by hypoglycemia (23/142, 16.2%) and hyper- booked mothers who underwent emergency cesarean

bilirubinemia (11/142, 7.7%). There was a statistically sections (43.8%), highlighting the importance of this

422 ANN SAUDI MED 2017 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER WWW.ANNSAUDIMED.NET

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT IN NICU original article

variable as a risk factor for the admission of term in- Table 2. Reasons for admission of term infants to NICU

fants to ICUs. In addition, infants born to unbooked between 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015.

mothers have a higher risk of low birthweight, pre- Reason for NICU admission Number (%)

maturity, and birth asphyxia.26 In our study, one of the

Respiratory distress 52 (36.6)

three infants with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

was born to an unbooked mother. Hypoglycemia 23 (16.2)

In our study, we were able to discern the cause Jaundice 11 (7.7)

of admission in most infants. Analogous to previ-

ABO incompatibility 10 (7)

ous studies, respiratory complications were the pre-

dominant causes of NICU admissions, accounting for Rh incompatibility 1 (0.7)

36.6% of all term admissions in our unit.20 Similarly, in Congenital anomalies 27 (19)

a retrospective cohort study of infants more than 36

Congenital heart disease 6 (4.2)

weeks gestational age, 49.3% were admitted to the

NICU because of respiratory distress.19 Hypoglycemia Surgical anomalies 6 (4.2)

and jaundice were responsible for 16.2% (23/142) and Diaphragmatic hernia 2 (1.4)

7.7% (11/142) of admissions, respectively. Unspecified

Imperforate anus 2 (1.4)

reasons accounted for almost 6% (8/142) of admis-

sions in our study; these included infants admitted Duodenal atresia 1 (0.7)

for less than 24 hours for observing hypoglycemia, Others 10 (7)

respiratory distress, or perinatal depression and those

Intrauterine growth

who received no intervention. In a retrospective co- retardation

10 (7)

hort study of all term admissions over one year in a

NICU in the United Kingdom, only 20 infants out of Necrotizing enterocolitis 1 (0.7)

174 (11.5%) admitted with hypoglycemia met the rec- Sepsis 4 (2.8)

ommended standard for a level III NICU admission.21

Hypoxic ischemic

Moreover, and in the same study, 105 of 389 (27%) encephalopathy

3 (2.1)

admitted infants at term were discharged or trans-

ferred within six hours of admission.21 Similarly, in a Perinatal depression 2 (1.4)

retrospective cohort study of 19 NICUs in the United Thrombocytopenia 1 (0.7)

States that evaluated the admission of infants be-

Unspecified 8 (5.6)

tween 35 and 42 weeks gestational age, the mean

frequency of admissions without a perceptible cause

was 10.8%.27 Table 3. Adjusted and crude odds ratios for NICU admission of term infants

The present study had several limitations. First, it and associated factors.

was a single-center experience. A single center serves Crude OR Adjusted OR

Covariate P value P value

a population that might have different characteristics (95% CI) (95% CI)*

from others, thus limiting the generalizability of the National 0.41 0.39

results of this study. Furthermore, gestational age .001 .001

(Saudi citizen) (0.25, 0.69) (0.23, 0.68)

was not included in the regression model to test its

2.19 1.88

confounding effect on the risk of NICU admission. We Diabetes .01 .06

(1.19, 4.06) (0.98, 3.59)

also had limited access to information about the un-

Premature

booked mothers and could not ascertain whether they 9.54 10.27

rupture of .03 .03

(1.19, 76.32) (1.21, 86.92

received antenatal care in another center in order to membrane

better understand how the booking status affected

2.54 1.43

the risk of admission of infants to the NICU. Moreover, Induced labor <.001 .65

(1.57, 4.10) (0.29, 6.89)

we also did not have details about the neonatal hos-

Cesarean 2.65 1.96

pital stay and interventions received. This information <.001 .41

section (1.63, 4.31) (0.40, 9.57)

would help in identifying key areas on which to focus

*Adjusted for being non--Saudi, diabetes, premature rupture of membrane, induction of labor and

on when carrying out quality improvement plans. cesarean delivery. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. Comparing the observed and

In conclusion, we identified areas that should be predicted numbers of observation in each group using Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test was

not significant (chi-sqaure 9.46, P=.09) indicating that the model fit the observed data well.

targeted for the improvement of care as well as more

effective and efficient utilization of resources. First,

ANN SAUDI MED 2017 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER WWW.ANNSAUDIMED.NET 423

original article QUALITY IMPROVEMENT IN NICU

the population of non-nationals and unbooked moth- care or observation unit in order to alleviate some of

ers should be embraced by a health care system that the workload in the NICU, free more beds for admit-

can accommodate them and afford appropriate ante- ting high-risk neonates, and reduce the associated

natal and perinatal care for better outcomes. Second, costs.28,29

we believe that NICUs must review all admissions

and audit potentially avoidable admissions. Those Conflict of interest

admissions might be managed in an intermediate None.

REFERENCES

1. Hynan MT, Mounts KO, Vanderbilt DL. 2012 Jul;16(5):1053-62. frequency and obstetric risk factors associat-

Screening parents of high-risk infants for 11. Horowitz K, Feldman D, Stuart B, Borgida ed with term neonatal admissions to special

emotional distress: rationale and recommen- A, Ming Victor Fang Y, Herson V. Full-term care units. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013

dations. J Perinatol. 2013 Oct;33(10):748-53. neonatal intensive care unit admission in an Jun;53(3):277-82.

2. Polin RA, Denson S, Brady MT, Commit- urban community hospital: the role of respi- 21. Granger C, Okpapi A, Peters C, Camp-

tee on F, Newborn, Committee on Infectious ratory morbidity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal bell M. G578(P) Potentially preventable

D. Epidemiology and diagnosis of health Med. 2011 Nov;24(11):1407-10. unexpected term admissions to neonatal

care-associated infections in the NICU. Pedi- 12. Lynch CD, Zhang J. The research impli- intensive care (nicu). Archives of Disease in

atrics. 2012 Apr;129(4):e1104-9. cations of the selection of a gestational age Childhood. 2015;100:A263.

3. Crenshaw JT. Healthy Birth Practice #6: estimation method. Paediatr Perinat Epide- 22. Dare MR, Middleton P, Crowther CA,

Keep Mother and Baby Together- It’s Best for miol. 2007 Sep;21(Suppl 2):86-96. Flenady VJ, Varatharaju B. Planned early

Mother, Baby, and Breastfeeding. J Perinat 13. Battaglia FC, Lubchenco LO. A prac- birth versus expectant management (waiting)

Educ. 2014 Fall;23(4):211-7. tical classification of newborn infants by for prelabour rupture of membranes at term

4. Bigelow A, Power M, MacLellan-Peters J, weight and gestational age. J Pediatr. 1967 (37 weeks or more). Cochrane Database Syst

Alex M, McDonald C. Effect of mother/infant Aug;71(2):159-63. Rev. 2006 Jan 25(1):CD005302.

skin-to-skin contact on postpartum depres- 14. Screening guidelines for newborns at risk 23. Grace L, Greer RM, Kumar S. Perina-

sive symptoms and maternal physiological for low blood glucose. Paediatr Child Health. tal consequences of a category 1 caesar-

stress. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004 Dec;9(10):723-40. ean section at term. BMJ Open. 2015 Jul

2012 May-Jun;41(3):369-82. 15. Executive summary: Neonatal encepha- 29;5(7):e007248.

5. Dumas L, Lepage M, Bystrova K, Matthie- lopathy and neurologic outcome, second 24. Ruth CA, Roos N, Hildes-Ripstein E,

sen AS, Welles-Nystrom B, Widstrom AM. edition. Report of the American College of Brownell M. The influence of gestational

Influence of skin-to-skin contact and room- Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force age and socioeconomic status on neonatal

ing-in on early mother-infant interaction: a on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Obstet Gyne- outcomes in late preterm and early term

randomized controlled trial. Clin Nurs Res. col. 2014 Apr;123(4):896-901. gestation: a population based study’. BMC

2013 Aug;22(3):310-36. 16. Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Pap- Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012 Jun 29;12:62.

6. Harrison W, Goodman D. Epidemiologic ile LA, Baley JE, Benitz W, Cummings J, et al. 25. Chigbu B, Onwere S, Kamanu CI, Aluka

Trends in Neonatal Intensive Care, 2007- Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. C, Okoro O, Adibe E. Pregnancy outcome

2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 Sep;169(9):855- Pediatrics. 2014 Jun;133(6):1146-50. in booked and unbooked mothers in South

62. 17. Quinn CE, Sivasubramaniam P, Blevins Eastern Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2009

7. Hubbard M. Reducing admissions to the M, Al Hajajra A, Znait AT, Khuri-Bulos N, et Jun;86(6):267-71.

neonatal unit: A report on how one neonatal al. Risk factors for neonatal intensive care unit 26. Tucker A, Ogutu D, Yoong W, Nauta M,

service has responded to the ever increasing admission in Amman, Jordan. East Mediterr Fakokunde A. The unbooked mother: a co-

demand on neonatal cots. Journal of Neona- Health J. 2016 Jun 15;22(3):163-74. hort study of maternal and foetal outcomes

tal Nursing. 2006;12(5):172-76. 18. Battersby C, Michaelides S, Upton M, in a North London Hospital. Arch Gynecol

8. Rohininath T, O’Connell LA, Sheehan Rennie JM. On behalf of the Jaundice Work- Obstet. 2010 Apr;281(4):613-6.

K, Corcoran D, Matthews TG, Clarke TA. ing Group of the Atain (Avoiding Term Ad- 27. Ziegler KA, Paul DA, Hoffman M, Locke

Workload and short-term outcome of babies missions Into Neonatal units) programme, R. Variation in NICU Admission Rates With-

weighing 2,500 grams or more at birth ad- led by the Patient Safety team in NHS Im- out Identifiable Cause. Hosp Pediatr. 2016

mitted to the paediatric unit of the Rotunda provement. Term admissions to neonatal May;6(5):255-60.

Hospital. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005 units in England: a role for transitional care? 28. Busse M, Stromgren K, Thorngate L,

Feb;17(2):139-43. A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. Thomas KA. Parents’ responses to stress in

9. Tracy SK, Tracy MB, Sullivan E. Admis- 2017;7:e016050. the neonatal intensive care unit. Crit Care

sion of term infants to neonatal intensive 19. Burgess AP, Katz J, Pessolano J, Ponterio Nurse. 2013 Aug;33(4):52-9 (quiz 60).

care: a population-based study. Birth. 2007 J, Moretti M, Lakhi NA. Determination of an- 29. Vanderbilt D, Bushley T, Young R, Frank

Dec;34(4):301-7. tepartum and intrapartum risk factors associ- DA. Acute posttraumatic stress symptoms

10. Hoffmire CA, Chess PR, Ben Saad T, ated with neonatal intensive care unit admis- among urban mothers with newborns in

Glantz JC. Elective delivery before 39 weeks: sion. J Perinat Med. 2016 Jul 01;44(5):589-96. the neonatal intensive care unit: a pre-

the risk of infant admission to the neonatal 20. Alkiaat A, Hutchinson M, Jacques A, liminary study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009

intensive care unit. Matern Child Health J. Sharp MJ, Dickinson JE. Evaluation of the Feb;30(1):50-6.

424 ANN SAUDI MED 2017 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER WWW.ANNSAUDIMED.NET

Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction

prohibited without permission.

Вам также может понравиться

- Care NewbornДокумент17 страницCare NewbornAndrea EusebiОценок пока нет

- Harriet Lane - NeonatologyДокумент27 страницHarriet Lane - Neonatologyrichardcypher12Оценок пока нет

- Ukite 2009Документ69 страницUkite 2009pikacu196100% (1)

- Picu Ready RecknerДокумент2 страницыPicu Ready RecknerPranitha Reddy0% (1)

- Care of The Well NewbornДокумент17 страницCare of The Well NewbornGermán López Valencia100% (1)

- Follow-upoftheNICUPatient Medscape FormatДокумент65 страницFollow-upoftheNICUPatient Medscape FormatJohn ParudaОценок пока нет

- Bob Peripheral Nerve Blocks AspanДокумент70 страницBob Peripheral Nerve Blocks AspanPrunaru BogdanОценок пока нет

- Pediatrics 2012 Yee E298 304Документ9 страницPediatrics 2012 Yee E298 304Amber CarterОценок пока нет

- DownloadДокумент6 страницDownloadKai GgОценок пока нет

- Pediatrics 2002 Mortality in Low Birth Weight Infants According To Level of Neonatal Care at Hospital BirthДокумент7 страницPediatrics 2002 Mortality in Low Birth Weight Infants According To Level of Neonatal Care at Hospital Birthafrizal_deafzОценок пока нет

- Effect of SSCДокумент7 страницEffect of SSCgarethОценок пока нет

- HIV Cohorte UgandaДокумент10 страницHIV Cohorte UgandaMaluОценок пока нет

- 33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831Документ6 страниц33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831AnggaОценок пока нет

- R. Irvian1Документ5 страницR. Irvian1Ermawati RohanaОценок пока нет

- Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Admissions and Their Associations With Late Preterm Birth and Maternal Risk Factors in A Population-Based StudyДокумент1 страницаNeonatal Intensive Care Unit Admissions and Their Associations With Late Preterm Birth and Maternal Risk Factors in A Population-Based StudyRizky D'zul GranaОценок пока нет

- Knowledge Level and Determinants of Neonatal Jaundice A Cross-Sectional Study in The Effutu Municipality of GhanaДокумент10 страницKnowledge Level and Determinants of Neonatal Jaundice A Cross-Sectional Study in The Effutu Municipality of GhananicloverОценок пока нет

- Early Enteral Feeding and Nosocomial Sepsis in Very Low Birthweight InfantsДокумент4 страницыEarly Enteral Feeding and Nosocomial Sepsis in Very Low Birthweight InfantsaripbudiboyОценок пока нет

- Clinical Pathway Effectiveness: Riginal RticleДокумент5 страницClinical Pathway Effectiveness: Riginal RticleWynda NolaОценок пока нет

- Antenatal Fetal AssessmentДокумент7 страницAntenatal Fetal AssessmentFitriana Nur RahmawatiОценок пока нет

- Vaccination Information Fathers Receive During Pregnancy and Determinants of Infant Vaccination TimelinessДокумент13 страницVaccination Information Fathers Receive During Pregnancy and Determinants of Infant Vaccination TimelinessMěđ SimoОценок пока нет

- Pediatrics: DigestДокумент9 страницPediatrics: Digestdknight231Оценок пока нет

- Martin 2017Документ6 страницMartin 2017Peregrine Albertus Ricco AzaliОценок пока нет

- 9 JurnalДокумент83 страницы9 JurnalWanda AndiniОценок пока нет

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Among Premature Neonates: Prevalence, Mortality Rate and Risk Factors of MortalityДокумент5 страницAcute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Among Premature Neonates: Prevalence, Mortality Rate and Risk Factors of MortalityInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Low Birth Weight Prevalence, Risk Factors, Outcomes in Primary Health Care Setting: A Cross-Sectional StudyДокумент5 страницLow Birth Weight Prevalence, Risk Factors, Outcomes in Primary Health Care Setting: A Cross-Sectional Studyyubi arsanaОценок пока нет

- Study of Clinical Profile of Late Preterms at Tertiary Care Hospital, BangaloreДокумент11 страницStudy of Clinical Profile of Late Preterms at Tertiary Care Hospital, BangaloreInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Dehydration of NewbornДокумент7 страницJurnal Dehydration of NewbornRSU Aisyiyah PadangОценок пока нет

- Neonatal Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infants From The NICHD Neonatal Research NetworkДокумент14 страницNeonatal Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infants From The NICHD Neonatal Research NetworkKattia FloresОценок пока нет

- PYMS TamizajeДокумент6 страницPYMS TamizajeKevinGallagherОценок пока нет

- Impact of Staffing On Bloodstream Infections in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitДокумент5 страницImpact of Staffing On Bloodstream Infections in The Neonatal Intensive Care Unitزينب محمد عبدОценок пока нет

- InformaciónДокумент6 страницInformaciónVIOLETA JACKELINE ARMAS CHAVEZОценок пока нет

- 2018 Article 1130Документ9 страниц2018 Article 1130Naman KhalidОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S1028455919300178 Main PDFДокумент5 страниц1 s2.0 S1028455919300178 Main PDFRadinal PrayitnoОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Risk FX SepsisДокумент7 страницJurnal Risk FX SepsiswilmaОценок пока нет

- Hypospadias and Early Gestation Growth Restriction in InfantsДокумент8 страницHypospadias and Early Gestation Growth Restriction in InfantsNaveed HussainОценок пока нет

- Congenital Anomalies Parents Concerns and Opinions To - 2018 - European JournaДокумент1 страницаCongenital Anomalies Parents Concerns and Opinions To - 2018 - European Journaburak yolcuОценок пока нет

- Maternal and Neonatal Risk Factors For Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Term Neonates in Cyprus - A Prospective Case-Control StudyДокумент9 страницMaternal and Neonatal Risk Factors For Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Term Neonates in Cyprus - A Prospective Case-Control StudyAnapaolaОценок пока нет

- Hypoglycemia and Associated Comorbidities Among Newborns of Mothers With Diabetes in An Academic Tertiary Care CenterДокумент15 страницHypoglycemia and Associated Comorbidities Among Newborns of Mothers With Diabetes in An Academic Tertiary Care CenterrimzeenafeeshaОценок пока нет

- Endoscopic Intervention and Cholecystectomy in Pregnant Women With Acute Biliary Pancreatitis Decreases Early ReadmissionsДокумент19 страницEndoscopic Intervention and Cholecystectomy in Pregnant Women With Acute Biliary Pancreatitis Decreases Early ReadmissionsCarlos Altez FernandezОценок пока нет

- Risk Factors For Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia: A Case Control StudyДокумент5 страницRisk Factors For Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia: A Case Control StudyRajba NazalahОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Investigation 2022 Abdul Hamid Impact of The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic On Breastfeeding During and PDFДокумент8 страницPediatric Investigation 2022 Abdul Hamid Impact of The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic On Breastfeeding During and PDFHaslina Abdul HamidОценок пока нет

- Predicting In-Hospital Length of Stay For Very-Low-Birth-Weight Preterm Infants Using Machine Learning TechniquesДокумент8 страницPredicting In-Hospital Length of Stay For Very-Low-Birth-Weight Preterm Infants Using Machine Learning TechniquesGabriel Ferreira MassonОценок пока нет

- Keac 372Документ12 страницKeac 372Abi ArifiОценок пока нет

- Expectant Versus Aggressive Management in Severe Preeclampsia Remote From TermДокумент6 страницExpectant Versus Aggressive Management in Severe Preeclampsia Remote From Termmiss.JEJEОценок пока нет

- Antenatal and Intrapartum Care of The High-Risk Infant: Avroy A. FanaroffДокумент44 страницыAntenatal and Intrapartum Care of The High-Risk Infant: Avroy A. FanaroffwilmaОценок пока нет

- Service Excellence 2012Документ8 страницService Excellence 2012FifiОценок пока нет

- Neonatal and Obstetric Risk Assessment (NORA) Pregnancy Cohort Study in SingaporeДокумент7 страницNeonatal and Obstetric Risk Assessment (NORA) Pregnancy Cohort Study in SingaporePremier PublishersОценок пока нет

- Feto-Maternal Outcomes Following Caesarean SectionДокумент6 страницFeto-Maternal Outcomes Following Caesarean Sectionkirandhami1520Оценок пока нет

- Outcome of Teenage PregnancyДокумент5 страницOutcome of Teenage PregnancyKN DumpОценок пока нет

- Fetomaternal Outcome in Twin Pregnancies - A Retrospective Analysis From A Tertiary Care CentreДокумент5 страницFetomaternal Outcome in Twin Pregnancies - A Retrospective Analysis From A Tertiary Care CentreLouis HadiyantoОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0022347621002900 MainДокумент10 страниц1 s2.0 S0022347621002900 MainFarah PramestyОценок пока нет

- Del 153Документ6 страницDel 153Fan AccountОценок пока нет

- Impact On Delayed Newborn Bathing On Exclusive Breastfeed - 2019 - Journal of NeДокумент6 страницImpact On Delayed Newborn Bathing On Exclusive Breastfeed - 2019 - Journal of NeCarol HОценок пока нет

- Articulo de Tarea Grupo Seguridad VialДокумент10 страницArticulo de Tarea Grupo Seguridad VialAlexander ZapataОценок пока нет

- 2016 Relacion ANEMIA Con NEC y TransfusionesДокумент9 страниц2016 Relacion ANEMIA Con NEC y TransfusionesnadisjaviОценок пока нет

- Neonatal Complications of Term Pregnancy: Rates by Gestational Age Increase in A Continuous, Not Threshold, FashionДокумент6 страницNeonatal Complications of Term Pregnancy: Rates by Gestational Age Increase in A Continuous, Not Threshold, FashionAndreea BorislavschiОценок пока нет

- Prevalence and Association of Cost of Hospital Malnutrition in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of Sanglah Hospital During 2015Документ7 страницPrevalence and Association of Cost of Hospital Malnutrition in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of Sanglah Hospital During 2015Inez Ann Marie TumbelakaОценок пока нет

- Less Is More Modern NeonatologyДокумент11 страницLess Is More Modern NeonatologyEN BUОценок пока нет

- Risk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyДокумент9 страницRisk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyAhmad SyaukatОценок пока нет

- Relation Between Infant Feeding and Infections During The First Six Months of LifeДокумент7 страницRelation Between Infant Feeding and Infections During The First Six Months of Lifeserdar günübirlikОценок пока нет

- Maternal & Perinatal Outcome of Fever in Pregnancy in The Context of DengueДокумент5 страницMaternal & Perinatal Outcome of Fever in Pregnancy in The Context of DengueLola del carmen RojasОценок пока нет

- Al Riyami-2020-Respiratory Distress Syndrome IДокумент6 страницAl Riyami-2020-Respiratory Distress Syndrome IHidayatt NurulОценок пока нет

- Common Problems in the Newborn Nursery: An Evidence and Case-based GuideОт EverandCommon Problems in the Newborn Nursery: An Evidence and Case-based GuideGilbert I. MartinОценок пока нет

- Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementОт EverandDiabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementОценок пока нет

- Jurnal NeuroДокумент6 страницJurnal NeuroSiti WahyuningsihОценок пока нет

- Amelia Sung MAternity VSIM Guided ReflectionДокумент2 страницыAmelia Sung MAternity VSIM Guided Reflectionmeisha thompsonОценок пока нет

- Section - 028 - Edentulous Histology - Tissue ConditioningДокумент13 страницSection - 028 - Edentulous Histology - Tissue ConditioningDentist HereОценок пока нет

- How To Make Hospital Noise FreeДокумент4 страницыHow To Make Hospital Noise FreeDebobrota K. SarkerОценок пока нет

- Oral Histology NotesДокумент18 страницOral Histology NotesKhalil Raziq100% (1)

- Hospital Research Doh Requirements - PadilloДокумент15 страницHospital Research Doh Requirements - PadilloMaylene PadilloОценок пока нет

- Nursing Gynaecology Dissertation TopicsДокумент5 страницNursing Gynaecology Dissertation TopicsWriteMyCollegePaperCanada100% (1)

- Gestational Hypertension (Preeklampsia) - Dr. Yudianto Budi Saroyo, SpOG (K)Документ44 страницыGestational Hypertension (Preeklampsia) - Dr. Yudianto Budi Saroyo, SpOG (K)Feny renitaОценок пока нет

- R633199 PDFДокумент1 страницаR633199 PDFChirag RohitОценок пока нет

- Diatermo MB 122 and MB 160 Mono-Bipolar: Cautery & ElectrosurgeryДокумент13 страницDiatermo MB 122 and MB 160 Mono-Bipolar: Cautery & ElectrosurgeryDani Daniela100% (1)

- Transvaginal Scan Transabdominal ScanДокумент4 страницыTransvaginal Scan Transabdominal ScanJudy Ann CristeОценок пока нет

- Surgical Management of Yoke Gall in A Bull - 2 PDFДокумент1 страницаSurgical Management of Yoke Gall in A Bull - 2 PDFMudassar Gujjar100% (1)

- Guidelines For Surfactant AdministrationДокумент4 страницыGuidelines For Surfactant AdministrationDella Elvina RoeslandОценок пока нет

- CABG - On Pump Vs Off Pump - AHA 2005Документ7 страницCABG - On Pump Vs Off Pump - AHA 2005odiseu81Оценок пока нет

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris PertemuanДокумент3 страницыTugas Bahasa Inggris PertemuanNova Sri MugiyantiОценок пока нет

- ASQ1Документ14 страницASQ1janakaОценок пока нет

- Epithelial Ovarian CancerДокумент14 страницEpithelial Ovarian Cancernautilus81Оценок пока нет

- TMH ResumeДокумент2 страницыTMH Resumeapi-257873078Оценок пока нет

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris IISДокумент3 страницыTugas Bahasa Inggris IISenaf fantiahОценок пока нет

- INISS Prospectus Part A JULY-2023Документ37 страницINISS Prospectus Part A JULY-2023Vaibhav TrivediОценок пока нет

- OD DR New TemplateДокумент9 страницOD DR New TemplateJean MoralesОценок пока нет

- In Vitro FertilizationДокумент10 страницIn Vitro FertilizationMoe AboamОценок пока нет

- Perfect-Use and Typical-Use Pearl Index of A Contraceptive Mobile AppДокумент6 страницPerfect-Use and Typical-Use Pearl Index of A Contraceptive Mobile AppRaven DelargeОценок пока нет

- Children 10 00784 v2Документ11 страницChildren 10 00784 v2Carmela ParasОценок пока нет

- Lesson 13Документ108 страницLesson 13Rizalyn Padua ReyОценок пока нет

- Levothyroxine SodiumДокумент4 страницыLevothyroxine SodiumJasmine LarsenОценок пока нет