Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Patients' Perceptions of Patient Education On Psychiatric Inpatient Wards: A Qualitative Study

Загружено:

avratОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Patients' Perceptions of Patient Education On Psychiatric Inpatient Wards: A Qualitative Study

Загружено:

avratАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

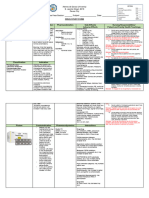

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2010, 17, 335–341

Patients’ perceptions of patient education on

psychiatric inpatient wards: a qualitative study jpm_1530 335..341

H . H Ä T Ö N E N 1 r n m n s c , R . S U H O N E N 2 r n p h d , H . WA R R O 3 r n m n s c ,

A. PITKÄNEN4 rn mnsc & M. VÄLIMÄKI5 rn phd

1

Doctoral student, University of Turku, Department of Nursing Science/Municipality of Imatra, Hospital District

of South Carelia, 2Professor (acting), 3Ward manager, University of Turku, Department of Nursing Science,

4

Doctoral student, University of Turku, Department of Nursing Science/Pirkanmaa Hospital District, and

5

Professor, University of Turku, Department of Nursing Science/Hospital District of South-West Finland,

Turku, Finland

Keywords: patient education, Accessible summary

psychiatric hospital, qualitative

study • A number of patient education programmes have been developed and implemented

in psychiatric nursing care to support patients’ information receiving. There is still

Correspondence:

a lack of knowledge about how patients themselves perceive patient education

H. Hätönen

programmes when they have been used on psychiatric inpatient wards.

University of Turku

Department of Nursing Science • In this study, patients with schizophrenia or related disorders described how they

Municipality of Imatra perceived IT-based patient education, conventional patient education with leaflets or

Hospital District of South Carelia patient education according to standard care during their hospital stay. In addition,

Sinivuokonkatu 10 areas for improvement were identified.

55100 Imatra • Patients’ perceptions of patient education varied depending on which patient

Finland education group they had participated in.

E-mail: heli.hatonen@utu.fi • Structured and systematically conducted patient education programmes on psychi-

Accepted for publication: 9 November atric wards were reportedly useful. However, no simple educational method suits

2009 every patient and therefore a combination of different education methods should be

used to meet patients’ individual needs. Moreover, nurse–patient interaction is still

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01530.x

an essential element of patient education whatever educational methods are used.

Abstract

This study describes patients’ perceptions of different types of patient education

interventions and areas where patient education should be improved on psychiatric

wards. Thematic interviews were conducted with 16 patients who had completed the

information technology (IT)-based patient education, conventional patient education

with leaflets or patient education according to ward standards during their hospital

stay. Data were analysed using inductive content analysis. Patients’ perceptions of

patient education varied depending on which patient education group they had par-

ticipated in. Patients participating in IT-based or conventional patient education per-

ceived education as a systematic and planned process. However, especially patients

in the patient education group applying ward standard education perceived patient

education as occasional information dissemination situations. To improve patient

education, patients suggested that it should be based on their individual needs and

offered with different methods systematically to all patients. The results indicate that

patients find structured and systematic patient education programmes useful. Different

educational methods should be used, not forgetting interaction between patient and

nurse, which was reportedly as an essential element of patient education.

© 2010 Blackwell Publishing 335

H. Hätönen et al.

study (RCT) with 311 patients randomly allocated to one

Introduction

of the three groups: (1) IT-based patient education; (2)

Schizophrenia is characterized by impaired ability to cope conventional patient education using standard leaflets; and

in daily life (Rossler et al. 2005). Together with medical (3) standard care. In the IT-based patient education group

treatment, patient education in addition to other psy- and conventional patient education group, five sessions

chosocial interventions is an essential method to support with staff were organized. In both groups, the sessions

patients’ capacity to manage their illness (Pekkala & Mer- focused on specific themes such as mental illness, treat-

inder 2002, Zygmunt et al. 2002). However, patients with ment, well-being, support and patients’ rights (Välimäki

schizophrenia in particular are dissatisfied with informa- et al. 2008).

tion provided during their treatment (Alexius et al. 2000, No patient education intervention itself is likely to

Ascher-Svanum et al. 2001). achieve positive outcomes if the education does not

A number of explanations have been proposed for respond to patients’ individual needs (Bodenheimer et al.

patients’ dissatisfaction with information provided. It has 2002). The key question that remains to be answered is

been assumed that the information offered by staff does not how patients themselves perceive the patient education

take account of patients’ individual needs (Feldmann et al. methods used on psychiatric wards. The aim of this quali-

2002, Sung et al. 2004). Moreover, there is a gap in the tative study to be reported here was to describe patients’

evidence supporting the benefits of tailored information for perceptions of different educational interventions and to

people with psychotic illness, because cognitive deficits due identify areas where patient education should be improved.

to schizophrenia and psychopharmaceutical medication

may impair patients’ capacity to receive and process new

information (Medalia & Lim 2004). In addition, various Method

other factors such as lack of insight (Aleman et al. 2006),

A descriptive qualitative approach was used to explore

motivation (Hill & Laugharne 2006) and support from

patients’ individual perceptions of what patient education

family members (Pharoah et al. 2006) have affected

contributes to patients (Clarke 2001, Grypdonck 2006).

patients’ information reception.

Qualitative research methods are appropriate when explor-

In general, patients desire information through diverse

ing social phenomena as perceived by individuals them-

methods together with discussions with staff (Proudfoot

selves (Malterud 2001).

et al. 2003). Patients themselves appreciate information on

illness and care in written format (Jorm et al. 2003).

However, written information alone with no chance to ask

Setting and sample

questions may confuse patients with cognitive deficits

(Strydom & Hall 2001). Thus, personal communication The data were collected at two psychiatric hospitals (nine

between patient and staff seems to be an important element study wards) in Southern Finland. The study population of

of patient education (Crowe et al. 2001). this qualitative study consisted of patients who had com-

More recently, patient education interventions using pleted the RCT study described above and its intervention

information technology (IT) have been used in mental (IT-based patient education, conventional patient educa-

health care (Lewis 2003) and patients have found them tion or standard care) while in hospital. Because the study

useful and convenient (Zabinski et al. 2004). IT-based sample consisted of patients from the RCT study, they

interventions offer patients self-paced learning, shorter- fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: age 18–65 years,

time involvement and more concise information com- able to speak Finnish and competent to give written

pared with face-to-face interventions (Jones et al. 2001, informed consent to participate in the study. All patients

Chou et al. 2004). They may also help compensate for had schizophrenia, schizotypal disorders or delusional dis-

cognitive deficits and enhance communication between orders (International Classification of Diseases – 10 criteria

patients and professionals (Bellucci et al. 2003, Ahmed & F20–29; WHO 1992).

Boisvert 2006). On the other hand, some patients have Convenience sampling was used to recruit patients dis-

reported deficiencies related to the individuality and cred- charged from psychiatric hospital during the middle period

ibility of information received by computer (Jones et al. of the RCT study (between August 2006 and January

2001). 2007). All eligible patients (n = 32) were systematically

This qualitative study is one part of a large research invited to participate in the study during data collection

project intended to generate information on IT use in period. They were contacted by letter and telephone and

mental health care. In this project, we implemented patient invited to participate in the interview about 3 months after

education programmes in a randomized controlled trial the patient education interventions.

336 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing

Patients’ perceptions of patient education

patient’s descriptions concerning ‘interaction’ were found

Patients interviewed

in the data set, a sentence or part of a sentence was coded

Out of the 32 eligible patients, seven were not reached and with a description of the thematic content characterizing

nine refused to participate in the study. Thus, 16 individu- the sentence. Subcategories were developed for these coded

als were willing to share their perceptions of patient edu- phrases by grouping together those with similar connota-

cation. Six patients had participated in IT-based patient tions. The set of main categories was established by group-

education, six in conventional patient education and four ing together subcategories with similar meaning (Silverman

in standard care. The patients interviewed were 11 men 2001). The analysis was carried out by the first author.

and 5 women, in the age range from 20 to 64 years (mean

35.7, SD 11.92). Half of the patients were on pension. The

duration of disorders varied between 1 month and 32 years Ethical considerations

(mean 12.3, SD 9.26).

The study procedure was evaluated by the local hospital

district’s ethics committee. Permission to conduct the study

Data collection was obtained from the organization’s directors. Written

The interviews were carried out by one researcher. Patients informed consent was obtained from each participant.

were interviewed at psychiatric outpatient clinics or public They received oral and written information about the

libraries. The individual interviews were conducted using purpose of the study and their rights as participants. It was

an open-ended thematic interview guide piloted with two emphasized that participation in the study was voluntary

interviews and not changed thereafter. The main themes and refusal would not affect their care. To ensure partici-

discussed were: (1) patients’ description of how education pants’ anonymity, the data were treated in confidence by

sessions were conducted and (2) suggestions for improving changing all identification data into numerical form during

patient education on the psychiatric ward. Each theme was the analysis (ETENE 2001, Declaration of Helsinki 2004).

followed up in the dialogue between patient and inter-

viewer (Silverman 2001). Interviews were tape-recorded

with patients’ permission. The duration of the interviews Findings

ranged between 8 and 29 min.

The key elements of patient education

Analysis The analysis of patients’ perceptions of patient education

formed five key elements identifying patient education:

The data were analysed in two phases using inductive (1) procedure; (2) interaction; (3) educational method; (4)

qualitative content analysis (Denzin & Lincoln 2000). In environment; and (5) benefits.

the first phase, the aim was to explore how patients Procedure for patient education described the structure

described patient education. The transcribed interviews and content of how patient education was conducted on

were read through to get a general picture of the material as psychiatric wards. Interaction of patient education was

a whole. Primary observations from the whole data set described through perceptions of communication and the

were then coded. Where the primary observations shared nurse–patient relationship. Educational method included

the same properties they were allocated to the same cat- descriptions of using educational methods as a part of

egory (Silverman 2001). This served to reveal the following patient education and possible additional support for

five key elements describing patient education identified receiving information. Environment was described in terms

from the data: (1) procedure; (2) interaction; (3) educa- of physical environment possibly affecting patients’ infor-

tional method; (4) environment; and (5) benefits. These mation receiving. Further, benefits described patients’ per-

elements were used as a framework for second analysis ceptions of the advantages of the patient education for

phase. everyday coping with their illness.

In the second analysis phase, the aim was to describe

patients’ perceptions in different educational groups (IT-

based patient education, conventional patient education,

Patients’ perceptions of patient education methods

standard care) and to explore patients’ suggestions for

improvements in patient education. The analysis was per- The five key elements of patient education were used as a

formed separately for each patient education group to framework to describe patients’ perceptions of IT-based

examine how each of the five key elements of patient patient education, conventional patient education and

education was described in the data. For example, when a patient education according to the standard care.

© 2010 Blackwell Publishing 337

H. Hätönen et al.

IT-based patient education Yes there was it [patient education] sometimes. I do not

The procedure for IT-based patient education was remember details right now.

described by patients in terms of systematic patient educa- Some patients reported that they did not receive any

tion sessions. This meant that the timing and content of information at all.

patient education were planned in advance and it was a The nurse–patient interaction reportedly lacked discus-

step-by-step process as stated in following quotation: sions on patients’ situation. Some patients reported that the

We had a schedule and in each session a specific topic interaction lacked appropriate respect and individuality.

was discussed. They felt that their information receiving was not sup-

The nurse–patient interaction was described in terms of ported with any educational method and the patients did

individual discussions when the content of patient educa- not mention if the environment had any effect on how they

tion was integrated into the patient’s life situation through received information. Considering the benefits of patient

cooperative discussions. By contrast, interaction was education, patients reported that the information received

described as mechanical information dissemination when was mainly meaningless to them.

it was perceived as delivery of information from nurse to

patient rather than a process responding to patients’ needs.

Suggestions for the further development of

The use of a computer was perceived to give additional

patient education

support to patients’ information receiving, but some

patients were concerned if the use of computer affected the The key elements of patient education were used as a

confidentiality. Patients described an environment that was framework to describe patients’ suggestions for improving

peaceful and suitable for the purpose as supportive for IT-based patient education, conventional patient education

information receiving while an environment with interrup- and patient education according to the standard care.

tions and disturbances was perceived to hinder patients’

information receiving. Considering the benefits of patient IT-based patient education

education, some patients thought that the focus was on Patients’ suggestions related to the development of pro-

patients’ independent coping with illness. However, some cedure were described in terms of individual planning

patients considered the information received to be impor- and more extensive content of patient education. Patients

tant, but useless for everyday coping. reported that their individual situation should be consid-

ered in planning patient education as described in the fol-

Conventional patient education

lowing quotation:

Patients who participated in the conventional patient

In what situation someone is, it is important. If someone

education described the procedure of patient education

is very tired or something, there should be a change to

in terms of planned patient education sessions with the

rest before those sessions.

content based on leaflets as described by one patient:

More extensive content meant including more examples

We had several sessions where we had certain time to go

of patients descriptions in the content.

through those leaflets.

To develop the educational method, patients suggested

The nurse–patient interaction was described by some

that the options of IT should be utilized more widely. This

patients as helpful. This meant open and confidential dis-

meant using more pictures, voice clips and interactive tasks

cussions. By contrast, some patients in this group reported

in the portal. Environment for patient education should be

that interaction was rather passive, a one-way informing

peaceful and undisturbed. Moreover, having computers on

situation. The use of the leaflets was perceived to give

the ward was suggested to support patients’ independent

additional support to patients’ information receiving.

information seeking. No suggestions on interaction or

Patients reported that it was useful to recap information

benefits were mentioned by patients in this group.

received independently from leaflets. The patients did not

mention any effect of the environment on receiving infor-

Conventional patient education

mation. Regarding the benefits of patient education, some

Regarding procedure, patients’ suggestions included

patients thought that the information received was useful

involving patients in planning, recapping of content and

for their independent coping with illness, while some

detailed information. Patients reported that involving them

patients reported that the information seemed rather super-

in the planning of the patient education integrates this into

ficial to them.

their life situations.

Standard care Nurses should actively offer this [patient education] and

The procedure of patient education was described as occa- ask if the patient is ready for it. Then it is easier to

sional informing sessions as one patient put it: participate and think about those different topics.

338 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing

Patients’ perceptions of patient education

Patients perceived it as useful that the content of the the impact of organizational factors, professional values

previous patient education session should be recapped at and skills on successful patient education (Deccache &

the beginning of the new session, and requested more Aujoulat 2001).

detailed information. In order to support patients to receive information in

Patients noted that interaction could be improved by psychiatric care, guidelines have been developed to enhance

creating active interaction through open communication the integration of patient education into treatment (NICE

and clearing up issues about which patients may be con- 2002, APA 2004, Duodecim 2008). However, the use of

cerned. They suggested that different educational materials standardized treatment procedures has emerged as a

should be used to support their information receiving. No concern about the loss of individuality (Miller & Kearney

suggestions for improving the environment and benefits 2004), which may put patients in a passive role. This is an

were made. important aspect in psychiatric care, where patients often

have problems in actively participating in their own treat-

Standard care ment (Hill & Laugharne 2006). In this study, patients

Patients’ suggestions for improving patient education pro- perceived interaction to be passive if information was

cedure were described in terms of systematic individual delivered to them through one-way mechanical sessions. As

practices. The patients were of the opinion that patient other studies have shown, interaction between patient and

education should be offered systematically to all patients nurse is an essential element of patient education (Crowe

taking into account their individual situation. Development et al. 2001, Pollock et al. 2004). Building a unique, thera-

of interaction included descriptions of individual interac- peutic and trusting relationship with each patient is crucial

tion. Patients considered that nurses should be active in in nursing (McQueen 2000). Therefore, staff’s skills in

creating respectful communication based on patients’ indi- providing systematic patient education through patient-

vidual situations. centred communication demands attention (Maguire &

To develop educational methods, patients wanted to Pitcheathly 2002).

receive information from different sources such as leaflets In this study, patients mentioned a need to use different

and the Internet as stated by one patient: patient education methods to support their information

And more different leaflets and new technology could receiving. This has already been found to be an effective

be used. (Murray et al. 2005, Haynes et al. 2008) and accepted

Patients also wanted to receive information from differ- method among patients (Jorm et al. 2003, Chou et al.

ent professionals and from other patients to get different 2004). IT especially as a part of patient education is quite

viewpoints. Patients in this group did not provide sugges- new in the field of psychiatric care (Lewis 2003). In good

tions for development of environment and benefits. hands the use of IT may shift the role of the patient from

that of a passive recipient to that of an active consumer of

health information. Therefore, it is important that health

Discussion

professionals are ready for this transformation and have

Patients’ perceptions of the patient education intervention the skills to guide patients to use the health information

varied depending on whether they had participated in available on the Internet safely (Mc Mullan 2006).

IT-based patient education, conventional patient educa- Regarding the limitations of this study, the number of

tion or standard care. Earlier studies have also shown that patients who refused to participate in this study was high

patients’ experiences of patient education vary (Feldmann (50%). Thus, the patient selection may have been biased

et al. 2002). In the present study, patients participating in that less motivated and incompetent patients were

in IT-based or conventional patient education perceived excluded from the study. Participants were also younger

education as a systematic and planned process. However, than patients in psychiatric hospitals in general (National

especially patients in the patient education group applying Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health

standard care perceived patient education as occasional 2008) and age-related computer literacy might contribute

information dissemination situations. These results may be to the successful realization of IT-based patient education

signs of psychiatric illness and poor insight (Zygmunt et al. (Or & Karsh 2009). These results might therefore give too

2002). On the other hand, our study showed that patients positive impression of patient education methods used in

with similar psychiatric illness in the same patient educa- this study. Additionally, the length of the interviews varied

tion group perceived patient education differently. We may a lot, potentially affecting the quality and depth of data.

therefore assume that there are aspects, other than the Patients with schizophrenia may also have severe manifes-

illness itself, affecting patients’ perceptions of patient edu- tations of psychiatric illness affecting their responses in the

cation. This is also supported by literature mentioning interviews. However, to ensure the quality of the data, the

© 2010 Blackwell Publishing 339

H. Hätönen et al.

interviews were carried out by one research assistant with Bodenheimer T., Lorig K., Holman H., et al. (2002) Patient self-

extensive experience in psychiatric nursing and trained in management of chronic disease in primary care. The Journal of

the American Medical Association 288, 2469–2475.

data collection. The analysis was carried out by the first

Chou M.H., Lin M.F., Hsu M.C., et al. (2004) Exploring the

author, which may affect the results because of an emphasis self-learning experiences of patients with depression participat-

on the researchers’ own perceptions. To overcome this, the ing in a multimedia education program. Journal of Nursing

results were read by all members of the research group and Research 12, 297–306.

analysis was corroborated with quotations from the origi- Clarke A. (2001) Evaluation research in nursing and health care.

nal data. Because of these limitations, the findings remain Nurse Researcher 8, 4–14.

Crowe M., O’Malley J. & Gordon S. (2001) Meeting the needs of

tentative. Despite the limitations, the results still provide

consumers in the community: a working partnership in mental

valuable knowledge about the elements and the variations health in New Zealand. Journal of Advanced Nursing 35,

in patients’ perceptions of patient education carried out on 88–96.

psychiatric wards. Deccache A. & Aujoulat I. (2001) A European perspective:

common developments, differences and challenges in patient

education. Patient Education and Counseling 44, 7–14.

Conclusions Declaration of Helsinki (2004) Ethical principles for medical

research involving human subjects. Available at: http://

We can conclude that patients perceive structured and www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm (accessed 14 May 2009).

systematically conducted patient education programmes Denzin K.N. & Lincoln Y.S. (2000) Handbook of Qualitative

useful. Different educational methods should be used not Research. SAGE Publications, London.

ETENE (2001) Shared values in health care, common goals and

forgetting interaction between patient and nurse, which

principles. ETENE – publications 3. Available at: http://

patients perceived to be essential element of patient educa- www.etene.org/dokumentit/EteneENG.pdf (accessed 14 May

tion. However, one educational method alone may not be 2009).

sufficient for every patient and therefore different educa- Feldmann R., Hornung W.P., Prein B., et al. (2002) Timing of

tion methods should be used according to patients’ indi- psychoeducational psychotherapeutic interventions in schizo-

vidual needs. phrenic patients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical

Neuroscience 252, 115–119.

Grypdonck M.H.F. (2006) Qualitative health research in the era

of evidence-based practice. Qualitative Health Research 16,

Acknowledgments

1371–1385.

This project was supported by the Academy of Finland Haynes R.B., Ackloo E., Sahota N., et al. (2008) Interventions for

enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Sys-

(207384), the Hospital District of South Carelia special

tematic Reviews, Issue 2. Art. No. CD000011. DOI: 10.1002/

grant-in-aid (EVO 77), the Medical Research Fund of 14651858.CD000011.pub3.

Tampere University Hospital, the South Carelian Cultural Hill S.A. & Laugharne R. (2006) Decision making and informa-

Foundation and the Finnish Foundation of Nursing Edu- tion seeking preferences among psychiatric patients. Journal of

cation that are gratefully acknowledged. Mental Health 15, 75–84.

Jones R.B., Atkinson J.M., Coia D.A., et al. (2001) Randomised

trial of personalised computer based information for patients

References with schizophrenia. British Medical Journal 322, 835–840.

Jorm A.F., Griffiths K.M., Christensen H., et al. (2003) Providing

Ahmed M. & Boisvert C.M. (2006) Using computers as visual aids information about the effectiveness of treatment options to

to enhance communication in therapy. Computers in Human depressed people in the community: a randomized controlled

Behavior 22, 847–855. trial of effects on mental health literacy, help-seeking and symp-

Aleman A., Agrawal N., Morgan K.D., et al. (2006) Insight in toms. Psychological Medicine 33, 1071–1079.

psychosis and neuropsychological function: meta-analysis. Lewis D. (2003) Computers in patient education. Computers,

British Journal of Psychiatry 189, 204–212. Informatics, Nursing 21, 88–96.

Alexius B., Berg K. & Åberg-Wistedt A. (2000) Patient satisfac- Mc Mullan M. (2006) Patients using the Internet to obtain health

tion with the information provided at a psychiatric emergency information: how this affects the patient–health professional

unit. Patient Education and Counseling 40, 51–57. relationship. Patient Education and Counseling 63, 24–28.

American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2004) Practice Guide- McQueen A. (2000) Nurse–patient relationships and partnership

line for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. American in hospital care. Journal of Clinical Nursing 9, 723–731.

Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA. Maguire P. & Pitceathly C. (2002) Key communication skills and

Ascher-Svanum H., Rochford S., Cisco D., et al. (2001) Patient how to acquire them. British Medical Journal 325, 697–700.

education about schizophrenia: initial expectations and later Malterud K. (2001) Qualitative research: standards, challenges,

satisfaction. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 22, 325–333. and guidelines. Lancet 358, 483–488.

Bellucci D., Glaberman K. & Haslam N. (2003) Computer- Medalia A. & Lim R. (2004) Treatment of cognitive dysfunction

assisted cognitive rehabilitation reduces negative symptoms in in psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 10,

the severely mentally ill. Schizophrenia Research 59, 225–232. 17–25.

340 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing

Patients’ perceptions of patient education

Miller M. & Kearney N. (2004) Guidelines for clinical practice: anxiety and depression in general practice. Psychological

development, dissemination and implementation. International Medicine 33, 217–227.

Journal of Nursing Studies 41, 813–821. Rossler W., Salize H.J., van Os J., et al. (2005) Size of burden of

Murray E., Burns J., See Tai S., et al. (2005) Interactive Health schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. European Neuropsy-

Communication Applications for people with chronic disease. chopharmacology 15, 399–409.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 4. Art. No. Silverman D. (2001) Interpreting Qualitative Data. Methods for

CD004274. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004274.pub4. Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. SAGE Publications,

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2002) Schizo- London.

phrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management Strydom A. & Hall I. (2001) Randomized trial of psychotropic

of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care. Algorithms medication information leaflets for people with intellectual

and Pathways to Care. National Institute for Clinical Excel- disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 45, 146–

lence, London. 151.

National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Sung S., Hixson A. & Yorker B.C. (2004) Predischarge psy-

Health (2008) In-patient specialized psychiatric services 2006. choeducational needs in Taiwan: comparisons of psychiatric

[Psykiatrian erikoisalan laitoshoito 2006] Official Statistics of patients, relatives, and professionals. Mental Health Nursing

Finland, Health 8/2008. National Research and Development 25, 579–588.

Centre for Welfare and Health. Available at: http://www. The Finnish Medical Society Duodecim and the Finnish Psychiat-

stakes.fi/tilastot/tilastotiedotteet/2008/Tt08-08.pdf (accessed 16 ric Association (Duodecim) (2008) Schizophrenia. Current care

September 2009). summary. Available at: http://www.kaypahoito.fi/ (accessed 14

Or C. & Karsh B.-T. (2009) A systematic review of patient accep- May 2009).

tance of consumer health information technology. Journal of Välimäki M., Anttila M., Hätönen H., et al. (2008) Design and

the American Medical Informatics Association 16, 550–560. development process of patient-centered computer-based

Pekkala E. & Merinder L. (2002) Psychoeducation for schizophre- support system for patients with schizophrenia spectrum psy-

nia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 2. Art. choses. Informatics for Health and Social Care 33, 113–123.

No. CD002831. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002831. WHO (1992) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behav-

Pharoah F., Mari J., Rathbone J., et al. (2006) Family intervention ioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guide-

for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, lines. World Health Organisation, Geneva.

Issue 4. Art. No. CD000088. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. Zabinski M.F., Wilfley D.E., Calfas K.J., et al. (2004) An interac-

CD000088.pub2. tive psychoeducational intervention for women at risk of devel-

Pollock K., Grime J., Baker E., et al. (2004) Meeting the informa- oping an eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

tion needs of psychiatric inpatients: staff and patient perspec- Psychology 72, 914–919.

tives. Journal of Mental Health 13, 389–401. Zygmunt A., Olfson M., Boyer C.A., et al. (2002) Interventions

Proudfoot J., Goldberg D., Mann A., et al. (2003) Computerized, to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American

interactive, multimedia cognitive-behavioural program for Journal of Psychiatry 159, 1653–1664.

© 2010 Blackwell Publishing 341

Copyright of Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Вам также может понравиться

- NURS - FPX 5005 - Brendan Madden - Assessment - 2-1Документ9 страницNURS - FPX 5005 - Brendan Madden - Assessment - 2-1SohaibОценок пока нет

- Patient Education Practices in Psychiatric Hospital Wards: A National Survey in FinlandДокумент7 страницPatient Education Practices in Psychiatric Hospital Wards: A National Survey in FinlanddeeОценок пока нет

- Annales D 891 HÃ Tã Nen DissДокумент85 страницAnnales D 891 HÃ Tã Nen DissDen SinyoОценок пока нет

- Patient ParticipationДокумент8 страницPatient ParticipationJumania SeptarianiОценок пока нет

- Attitudes of US Medical Trainees Towards Neurology Education: "Neurophobia" - A Global IssueДокумент7 страницAttitudes of US Medical Trainees Towards Neurology Education: "Neurophobia" - A Global Issuealikhanomer5Оценок пока нет

- 182 604 1 PBДокумент10 страниц182 604 1 PBAngel Nikiyuluw100% (1)

- تنزيلДокумент9 страницتنزيلrazanyahya440Оценок пока нет

- Rapid Critical Appraisal 4Документ6 страницRapid Critical Appraisal 4api-316574434Оценок пока нет

- The Nurses' Knowledge and Attitudes Towards The Palliative CareДокумент10 страницThe Nurses' Knowledge and Attitudes Towards The Palliative CareZein AhmadОценок пока нет

- Informatics Final PaperДокумент8 страницInformatics Final Paperapi-500286673Оценок пока нет

- Nurses' Activities and Time Management During Home Healthcare VisitsДокумент10 страницNurses' Activities and Time Management During Home Healthcare VisitsEli LОценок пока нет

- Am I Doing The Right Thing Provider Perspectives On Improving Palliative Care in The Emergency Department 2009 Annals of Emergency MedicineДокумент9 страницAm I Doing The Right Thing Provider Perspectives On Improving Palliative Care in The Emergency Department 2009 Annals of Emergency MedicineTUTIK SISWATIОценок пока нет

- Doctor-Patient Knowledge Transfer Innovative Technologies and Policy ImplicationsДокумент9 страницDoctor-Patient Knowledge Transfer Innovative Technologies and Policy ImplicationsAlexander DeckerОценок пока нет

- European Journal of Oncology Nursing: A B C AДокумент8 страницEuropean Journal of Oncology Nursing: A B C AfitrilihawaОценок пока нет

- archivev3i3MDIwMTMxMDIy PDFДокумент9 страницarchivev3i3MDIwMTMxMDIy PDFLatasha WilderОценок пока нет

- TOPICДокумент8 страницTOPICKeep smileОценок пока нет

- Tutor - Critical AppraisalДокумент8 страницTutor - Critical AppraisalPriyanka TanwarОценок пока нет

- Writing AbstractДокумент9 страницWriting AbstractDeva FaradinaОценок пока нет

- Infeksi Nifas PublisherДокумент4 страницыInfeksi Nifas PublisherYayha AgathaaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ11 страницChapter 1Yuuki Chitose (tai-kun)Оценок пока нет

- Health Education and The Pedagogical Role of The NДокумент9 страницHealth Education and The Pedagogical Role of The NJonah Micah Milan MangacoОценок пока нет

- Nurses' Knowledge About End-of-Life Care: Where Are We?Документ6 страницNurses' Knowledge About End-of-Life Care: Where Are We?Ritika AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Nurse Education Today: Ana M. Grilo, Margarida C. Santos, Joana S. Rita, Ana I. GomesДокумент5 страницNurse Education Today: Ana M. Grilo, Margarida C. Santos, Joana S. Rita, Ana I. GomesShiee Nevhie ParaDinata WapersОценок пока нет

- Determinants of Medical Students' Empathy During Clinical RotationДокумент9 страницDeterminants of Medical Students' Empathy During Clinical RotationIJPHSОценок пока нет

- Nurse Education in Practice: Nicole Defenbaugh, Noreen E. ChikotasДокумент6 страницNurse Education in Practice: Nicole Defenbaugh, Noreen E. ChikotasjovanaОценок пока нет

- Surgery Ward Journal ArticleДокумент23 страницыSurgery Ward Journal ArticleJonathan MangawiliОценок пока нет

- Communication Skills in Medical Education: An Integrated ApproachДокумент13 страницCommunication Skills in Medical Education: An Integrated ApproachMedicina IcesiОценок пока нет

- Patient Education As An Information System, Healthcare Tool and InteractionДокумент7 страницPatient Education As An Information System, Healthcare Tool and InteractionARPINAОценок пока нет

- It Is What It IsДокумент9 страницIt Is What It IsWU CHANGОценок пока нет

- Annalsofoncology Resumo Munique 2018Документ2 страницыAnnalsofoncology Resumo Munique 2018Fatima AlchadlaouiОценок пока нет

- Religious and Spiritual Assessment: A Standardized Patient Curriculum InterventionДокумент7 страницReligious and Spiritual Assessment: A Standardized Patient Curriculum InterventiondeniОценок пока нет

- Communicative and Pedagogical Strategies in Nurses' andДокумент11 страницCommunicative and Pedagogical Strategies in Nurses' andBheru LalОценок пока нет

- 13 Gentry Nursing PDFДокумент14 страниц13 Gentry Nursing PDFIstiqomahsejatiОценок пока нет

- Effectofcarereducationon Functionalabilitiesofpatients WithstrokeДокумент7 страницEffectofcarereducationon Functionalabilitiesofpatients WithstrokeDan Gerald Alcido SalungaОценок пока нет

- A Systematic Review of The Literature On Health Literacy in Nursing EducationДокумент5 страницA Systematic Review of The Literature On Health Literacy in Nursing EducationKusrini Kadar SyamsalamОценок пока нет

- Research ProposalДокумент17 страницResearch Proposalapi-542965039Оценок пока нет

- Exploring Islamic Based Caring Practice in Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative StudyДокумент10 страницExploring Islamic Based Caring Practice in Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative StudyineОценок пока нет

- The Importance of Health Literacy in Physiotherapy Practice: Andrew M Briggs and Joanne E JordanДокумент3 страницыThe Importance of Health Literacy in Physiotherapy Practice: Andrew M Briggs and Joanne E JordanMhmd IrakyОценок пока нет

- JHPN 24 E151Документ8 страницJHPN 24 E151MentiEndah dwi SeptianiОценок пока нет

- Realizing The Potential of Nurses Role in Genetics and Genomic Health Care - An Integrated Review of The LiteratureДокумент5 страницRealizing The Potential of Nurses Role in Genetics and Genomic Health Care - An Integrated Review of The LiteratureIOSRjournalОценок пока нет

- Comparison of Nursing Care Perceptions Between Patients Who Had Surgical Operation and Nurses Who Provided Care To Those PatientsДокумент8 страницComparison of Nursing Care Perceptions Between Patients Who Had Surgical Operation and Nurses Who Provided Care To Those PatientsnasimhsОценок пока нет

- Part B Paper For Publication Including ReferencesДокумент22 страницыPart B Paper For Publication Including ReferencesNu DiouОценок пока нет

- Effective Healthcare Worker-Patient Communication in Hong Kong Accident and Emergency DepartmentsДокумент15 страницEffective Healthcare Worker-Patient Communication in Hong Kong Accident and Emergency Departmentssel selОценок пока нет

- Artikel Bahasa Inggris Alda Depi ArieДокумент7 страницArtikel Bahasa Inggris Alda Depi ArieAlda DepiariОценок пока нет

- A Cross-Sectional Study On Person-Centred Communication in The Care of Older People: The COMHOME Study ProtocolДокумент9 страницA Cross-Sectional Study On Person-Centred Communication in The Care of Older People: The COMHOME Study Protocolgladeva yugi antariОценок пока нет

- Noor StoryboardДокумент1 страницаNoor Storyboardapi-215323958Оценок пока нет

- ACC Comunicare LiljeroosДокумент8 страницACC Comunicare LiljeroosMiss OanaОценок пока нет

- BNur General - Paper 2 - Assignment - Qualitative Phenomenological Study Untold and Unexpected Clinical Practice StressДокумент7 страницBNur General - Paper 2 - Assignment - Qualitative Phenomenological Study Untold and Unexpected Clinical Practice StressywnngdchjbОценок пока нет

- Directing Student Response To Early Patient Contact by QuestionnaireДокумент7 страницDirecting Student Response To Early Patient Contact by QuestionnaireDagma V M AbramidesОценок пока нет

- Canadian Medical Education JournalДокумент10 страницCanadian Medical Education JournaldradeyasantosОценок пока нет

- Self-Efficacy of Internship Nursing Students in Dealing With Palliative PatientsДокумент8 страницSelf-Efficacy of Internship Nursing Students in Dealing With Palliative PatientsIntanAgustiFernandesОценок пока нет

- Health Case Studies 1512494009Документ258 страницHealth Case Studies 1512494009lisa weareОценок пока нет

- Application of Watson Caring Theory For Nurses in Pediatric Critical Care UnitДокумент12 страницApplication of Watson Caring Theory For Nurses in Pediatric Critical Care UnitLOUIS AUSTINE MORAN VILLADARESОценок пока нет

- BEME Guide 68Документ14 страницBEME Guide 68Malak ShaheenОценок пока нет

- 03 Kianian 2Документ7 страниц03 Kianian 2awaluzzikryОценок пока нет

- Knowledge Deficit Theory: Submitted By: Alex Kate Dela BSN 1 STEM A Submitted To: Ms. Rubilyn SumayloДокумент4 страницыKnowledge Deficit Theory: Submitted By: Alex Kate Dela BSN 1 STEM A Submitted To: Ms. Rubilyn Sumaylokassy yeonОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Medical Sciences 2011 8 (5) :397-401 Research Paper Communication Skills Training For Emergency NursesДокумент10 страницInternational Journal of Medical Sciences 2011 8 (5) :397-401 Research Paper Communication Skills Training For Emergency Nursesanon_543702124Оценок пока нет

- Patient Edu N Health LiteracyДокумент30 страницPatient Edu N Health LiteracyLaras Adythia PratiwiОценок пока нет

- Propedeutik 2 3 Dental FacultyДокумент214 страницPropedeutik 2 3 Dental FacultyVimal SuseeОценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationОт EverandRelationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationОценок пока нет

- Do's and Dont's in Writing Research QuestionsДокумент2 страницыDo's and Dont's in Writing Research QuestionsLisandrea BrownОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting Sleep: The Quality and Quantity of Sleep AreДокумент3 страницыFactors Affecting Sleep: The Quality and Quantity of Sleep AreBijali sinha100% (3)

- VSO Our Side of The Story Uganda - Full ReportДокумент68 страницVSO Our Side of The Story Uganda - Full ReportVSOОценок пока нет

- National Geographic March 2016Документ148 страницNational Geographic March 2016Anonymous Azxx3Kp9Оценок пока нет

- Soal PAS BIG Xi, SMT 3, OnlineДокумент10 страницSoal PAS BIG Xi, SMT 3, OnlineRivaldi Lukman HakimОценок пока нет

- NOFRNCompetencies Updated March2016 PDFДокумент63 страницыNOFRNCompetencies Updated March2016 PDFamandeep kaurОценок пока нет

- Treatment and Prevention of LeptospirosisДокумент7 страницTreatment and Prevention of LeptospirosisSherry FeliciaОценок пока нет

- LESSON 1 Occupational Health and Safety Policies and ProceduresДокумент11 страницLESSON 1 Occupational Health and Safety Policies and Procedurescky yarteОценок пока нет

- Risk Assessment - Working Ship SideДокумент3 страницыRisk Assessment - Working Ship SideSatya SatishОценок пока нет

- InvaginasiДокумент10 страницInvaginasimelchiadiОценок пока нет

- Test Bank Health Assessment in Nursing 6th Edition Weber KelleyДокумент9 страницTest Bank Health Assessment in Nursing 6th Edition Weber KelleyPhyllis Vandenberge100% (25)

- Child - AsthmaДокумент2 страницыChild - AsthmaCleoanne Gallegos0% (1)

- Effective Exercises For A Short FrenumДокумент2 страницыEffective Exercises For A Short FrenumlblessingerОценок пока нет

- Carmen Best Background InformationДокумент15 страницCarmen Best Background InformationKING 5 NewsОценок пока нет

- SF2 - NovemberДокумент9 страницSF2 - NovemberbethuelОценок пока нет

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases in MalesДокумент15 страницSexually Transmitted Diseases in MalesSam Raven AndresОценок пока нет

- Diabetes and Its Management: Rohit ThanageДокумент10 страницDiabetes and Its Management: Rohit ThanageRohit ThanageОценок пока нет

- q2 Grade 7 Health DLL Week 1Документ8 страницq2 Grade 7 Health DLL Week 1johann reyes0% (1)

- Moshi PDFДокумент109 страницMoshi PDFBillyjeTadlas100% (2)

- Physical Education Cambridge Progression Test P1 - ST6 (2022)Документ14 страницPhysical Education Cambridge Progression Test P1 - ST6 (2022)Givemore MuromboОценок пока нет

- IMPaCCT EU - Standards For Paediatric Palliative Care in EuropeДокумент8 страницIMPaCCT EU - Standards For Paediatric Palliative Care in EuropeSaraОценок пока нет

- Neerland2018 (Physiolo)Документ11 страницNeerland2018 (Physiolo)Noah Borketey-laОценок пока нет

- Renal Drug StudyДокумент3 страницыRenal Drug StudyRiva OlarteОценок пока нет

- Hygiene Funda 1 2nd SemДокумент22 страницыHygiene Funda 1 2nd Semlegion alexandersОценок пока нет

- Meperidine Hydro ChlorideДокумент4 страницыMeperidine Hydro Chlorideapi-3797941Оценок пока нет

- Cognitive - Behavioural Strategies in Crisis InterventionДокумент3 страницыCognitive - Behavioural Strategies in Crisis InterventionHugo Gonzalez EnriquezОценок пока нет

- Droplet InfectionsДокумент11 страницDroplet InfectionsdevОценок пока нет

- Service Quality Patient Satisfaction and Loyalty in The Bangladesh Healthcare SectorДокумент14 страницService Quality Patient Satisfaction and Loyalty in The Bangladesh Healthcare Sectorgubbare86Оценок пока нет

- Precision Medicine OncologyДокумент18 страницPrecision Medicine Oncologyaminudinrahman100% (1)

- Minimal Invasive Dentistry: Review ArticleДокумент4 страницыMinimal Invasive Dentistry: Review ArticleKarissa NavitaОценок пока нет