Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Dilemmas Posed by Self-Represented Litigants - The Dark Side

Загружено:

Justine ZhouОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Dilemmas Posed by Self-Represented Litigants - The Dark Side

Загружено:

Justine ZhouАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Australian Centre for Justice Innovation

Civil Justice Research Online

Access to Justice

4-15-2014

The Dilemmas Posed by Self-Represented Litigants

– The Dark Side

Tania Sourdin

Monash University, tania.sourdin@monash.edu

Nerida Wallace

Monash University

Follow this and additional works at: http://www.civiljustice.info/access

Part of the Civil Law Commons

Recommended Citation

Sourdin, Tania and Wallace, Nerida, "The Dilemmas Posed by Self-Represented Litigants – The Dark Side" (2014). Access to Justice.

Paper 32.

http://www.civiljustice.info/access/32

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Civil Justice Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Access to Justice by an

authorized administrator of Civil Justice Research Online. For more information, please contact alan.shanks@monash.edu.

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2713561

T. SOURDIN AND N. WALLACE 1

AUSTRAL IAN CENTRE FOR JUST ICE SYSTEM INNOVATION (ACJI)

MONASH UNIVERSITY

The Dilemmas Posed by

Self-Represented Litigants

– The Dark Side

1

Professor Tania Sourdin, Australian Centre for Justice Innovation (ACJI) at Monash University contact

Tania.Sourdin@Monash.edu and Nerida Wallace of Transformation Management Services contact

nerida.wallace@transformation.com.au Parts of this paper are drawn from E. Richardson, T. Sourdin

and N. Wallace, Self-Represented Litigants: Gathering Useful Information, Final Report (ACJI, Monash

University, Melbourne, 2012), available at http://www.civiljustice.info/srl/2/; and Self-Represented

Litigants: Literature Review (ACJI, Monash University, Melbourne, 2012.), available at

http://www.civiljustice.info/srl/1/.

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2713561

Introduction

There is limited information about self-represented litigants (SRLs) in Australia. Past

research has highlighted significant and continuing data and research gaps about the

demographics of those involved in court and tribunal processes and among those who

are without representation. 2 Some reports reveal information about SRLs, although

much available information is dated. For example, research conducted more than a

decade ago in the Family Court of Australia found that, 79 per cent of applicants and

88.4 per cent of respondents in children’s matters were SRLs. 3 In terms of family law

matters in the Federal Magistrate’s Court of Australia, by the year 2003, 70 per cent

of divorce matters concerned SRLs, and there are high numbers of SRLs in child

support and contravention applications. 4

More recent court reports suggests that SRLs are more likely to be active in certain

types of matters, for example the Federal Court of Australia, the majority of SRLs are

involved in migration appeals. 2 Overseas, more recent studies by Macfarlane in

Canada in 2012/13 indicate that 60 per cent of family litigants and 31 per cent of civil

litigants were self-represented, and of these, almost 40 per cent had income levels

above $CAN50,000. 5 The same Canadian research suggests that self-representation is

increasing in respect of litigated matters around the world. 6

Whilst many SRLs appear to be able to represent themselves with some limited

support it is not known how many ‘give up’ because they are unable to continue with

the often difficult task of continuing with litigation. The lack of demographic

information about SRLs (or indeed litigants in general) means that the issues

confronting this population are not adequately explored and there is little comparable

material collected across courts and tribunals to provide guidance about the support

required by this population. 7 The population may also be very diverse and made up of

those who have low levels of literacy or who confront significant access issues

because of their backgrounds and special needs.

2

See E. Richardson, T. Sourdin and N. Wallace, Self-Represented Litigants: Gathering Useful Information,

Final Report (ACJI, Monash University, Melbourne, 2012), available at http://www.civiljustice.info/srl/2/;

and Self-Represented Litigants: Literature Review (ACJI, Monash University, Melbourne, 2012.), available

at http://www.civiljustice.info/srl/1/. See also E. Richardson and T. Sourdin, ‘Mind the gap: making

evidence-based decisions about self-represented litigants’ (2013) 22(4) Journal of Judicial Administration

191–206.

3

ALRC, Part two: The costs of litigation in the Family Court of Australia (Australian Law Reform

Commission, Sydney, June 1999); see alsoJ. Dewar, B. Smith and C. Banks, Litigants in Person in the

Family Court of Australia – Research Report No 20 (Family Court of Australia, Canberra, 2000).

4

Federal Magistrates Court of Australia, Annual Report 2002–2003 (Canberra: Federal Magistrate’s

Court of Australia, 2003).

2

Federal Court of Australia, Annual Report 2010–2011 (Federal Court of Australia, Canberra, 2011), 43.

5

J. MacFarlane, National Research Study – Self Represented Litigant Project (2013) Canada, 2013),

available at www.representingyourselfcanada.com (accessed 4 April 2014)).

6

J. MacFarlane, National Research Study – Self Represented Litigant Project (2013) Canada, 2013),

available at www.representingyourselfcanada.com (accessed 4 April 2014)).

7

See E. Richardson, T. Sourdin and N. Wallace, Self-Represented Litigants: Gathering Useful Information,

Final Report (ACJI, Monash University, Melbourne, 2012), available at http://www.civiljustice.info/srl/2/;

and Self-Represented Litigants: Literature Review (ACJI, Monash University, Melbourne, 2012.), available

at http://www.civiljustice.info/srl/1/. See also E. Richardson and T. Sourdin, ‘Mind the gap: making

evidence-based decisions about self-represented litigants’ (2013) 22(4) Journal of Judicial Administration

191–206.

Self -Represented Litigants –The Dark Side 3

THE DILEMMAS POSED BY

SELF-REPRESENTED LITIGANTS

– THE DARK SIDE

There are other issues as the needs of this broad SRL population may be obscured by

a currently unknown, but probably small, proportion of the SRL population that is

regarded as ‘obsessive’,’ difficult’, engaged in ‘high conflict behaviour’ or more

simply as ‘mad, bad and dangerous.’ 8 It is this proportion of SRLs – according to many

commentators and people working in the justice sector - that appears to be resistant

to or unable to engage in litigation in a respectful, fair or timely manner and which

require more time, more energy are a greater focus of attention by those working

within courts and tribunals.

This paper is concerned with this group of SRLs, who may not be represented for a

range of reasons but who may, because of their behaviour, raise particular issues for

judicial officers, courts and tribunals and most importantly for the administration of

justice in the whole community. There is no specific or definitive data in Australia

about the size of this group or the impacts. However, there is some data about

mental health issues in the general community that is helpful. For example, large

scale studies in the United States in 2002 and 2008 9 suggest that more than 14% of

the United States population has a personality disorder and another 10% have

maladaptive personality traits.

Whilst many people with mental health issues may be able to represent themselves

successfully and others may be less likely to commence court proceedings

(particularly if suffering from depression and anxiety), some with personality

disorders or maladaptive traits may be more likely to be involved in conflict and be

less able to negotiate agreed outcomes.

In particular, the cohort with high conflict behaviours is more likely to be involved in

court proceedings because they are less likely to resolve issues at an early time or act

in a rational manner. It is also possible that some in this group are more likely to be

self represented because they are unable to afford representation or may be less

likely to maintain relationships with legal practitioners. In order to explore this

cohort, and in the absence of definitive data on the size of this group, it is necessary

to explore the reasons behind self-representation, common perceptions about SRLs

and the impacts on the judiciary as well as possible responses.

Reasons for Self-Representation

There are multiple terms used to describe those who do not have representation,

including litigants in person, pro se litigants, unrepresented litigants, and of course,

self-represented litigants. At times, a distinction is made between those who choose

8

Lady Caroline Lamb referring to Lord Byron in 1812.

9

Recent studies suggest that these figures may be higher although many personality disorders will not

generate high conflict behaviours. See B. Eddy, High conflict people in legal disputes (HCI Press, 2009.

See also US National Institute of Mental Health at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-

numbers-count-mental-disorders-in-america/index.shtml#Intro (accessed 11 April 2014).The 2007

Australian Mental Health Study in 2007 suggested the figure in Australia was 20% - See

http://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/ (accessed 11 April 2014).

4 Self Represented Litigants –The Dark Side

or prefer self-representation and those who are self-represented by circumstances

beyond their control, such as a lack of financial resources. In the latter case, a litigant

may be described as ‘unrepresented’, rather than ‘self-represented’. However, this

distinction is not consistently made in studies and reports on SRLs. Another issue with

terms is that some litigants may have partial assistance or be represented from time

to time, and these nuances may not be recorded by courts or support agencies, and

even if recorded, are rarely reported on.

Little is known about the characteristics of SRLs and the reasons why some litigants

are -self-represented. In Canada, attempts have been made to identify the following

types of SRLs: 10

1. SRLs with an overall lack of social (such as, education, financial, and

community/family support) resources;

2. Low-income SRLs with some social resources;

3. SRLs living with additional social barriers that interfere with accessing

justice;

4. SRLs unable to find an available lawyer and who wish to hire a lawyer;

5. SRLs who were previously represented;

6. SRLs in cases where representation is supposed to be unnecessary;

7. SRLs who could access representation but prefer to self-represent. 11

There is a perception that the number of SRLs is increasing and has been increasing

over the past 15 years, largely attributed in the literature to increased legal costs and

changes to legal aid funding. 12 Australia is not alone in reporting this perception, with

other countries, such as the United States, New Zealand, Canada and the United

10

M. Stratton, Alberta self-represented litigants mapping project – Final Report (Canadian Forum on Civil

Justice, Edmonton, Alberta, 2007)), cited in Canadian Forum on Civil Justice, Alberta Legal Services

Mapping Project, An Overview of Findings from the Eleven Judicial Districts Final Report (Canadian Forum

on Civil Justice, Edmonton, Alberta, July 2011), 89–91.

11

Canadian Forum on Civil Justice, Alberta Legal Services Mapping Project, An Overview of Findings from

the Eleven Judicial Districts Final Report (Canadian Forum on Civil Justice, Edmonton, Alberta, July 2011),

89–91.

12

Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee, Access to Justice (Commonwealth of

Australia, Canberra, December 2009); Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee,

Inquiry into the Australian Legal Aid System: First Report (Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 26

March 1997); Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee, Inquiry into the Australian

Legal Aid System: Second Report (Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, June 1997); Senate Legal and

Constitutional Affairs References Committee, Inquiry into the Australian Legal Aid System: Third Report

(Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, July 1998); Senate Legal and Constitutional References

Committee, Inquiry into Legal Aid and Access to Justice (Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, June

2004.). It was noted in by Australian Law Reform Commission in Managing Justice – A review of the

Federal Civil Justice System Report No 89 (Australian Government Print Services, Canberra, 2000) that

there was no clear statistical data to support the claim that SRLs were increasing. However, the Law

Council of Australia in Erosion of Legal Representation in the Australian Justice System Research Report

(February 2004) found that there had been a rise in SRLs based on a survey conducted and some

statistical data. This finding can be contrasted with an earlier report by the Family Court of Australia in

which it was reported that the number of SRLs who are unrepresented throughout the entire court

process are low: Self-represented Litigants – A Challenge Project Report December 2000–December 2002

(Family Court of Australia, 2003), 3.

Self -Represented Litigants –The Dark Side 5

THE DILEMMAS POSED BY

SELF-REPRESENTED LITIGANTS

– THE DARK SIDE

Kingdom, reporting an increase in the population of SRLs. 13 Studies conducted in

Australia provide data and evidence supporting the increase; however they provide

little information about why the increase is occurring and its impact on the courts. 13

Dewar et al suggest that a number of factors may lead to a person’s decision to

represent themselves in the Family Court:

difficulty obtaining legal aid either at all or for representation in court

proceedings;

the cost of legal services: these may be such that a litigant is unable to

afford them at all or that an individual may be encouraged to make a

cost/benefit calculation that the costs incurred in employing a legal

representative outweigh the risks of pursuing litigation without a lawyer;

disenchantment with lawyers;

related to the above, a view that family law is not ‘real law’ and therefore

the skills of a lawyer are not necessary;

a wish to use the court as a forum to air grievances or seek revenge or as

an instrument of harassment;

the growth in other sources of advice or assistance, such as Community

Legal Centres, support groups or Legal Aid bodies; or

the simplification of court procedures. 14

Other reasons for self-representation may include a belief in the merits of the case

and a person’s view that they are the best person to present their case instead of a

lawyer. 15 Some SRLs may choose to represent themselves even when holding a grant

13

R. Moorhead and M. Sefton, Litigants in person. Unrepresented litigants in first instance proceedings

(Department of Constitutional Affairs Research Series 2/05, England & Wales, 2005), available at

http://www.familieslink.co.uk/download/july07/DCA%20view%20of%20LIPs.pdf (accessed 19 March 2014);

K. Williams, Litigants in person: a literature review – Research Summary 2/11 (Ministry of Justice, United

Kingdom, June 2011); M. Smith, E. Banbury and S. Ong, Self-Represented Litigants: An Exploratory Study

of Litigants in Person in the New Zealand Criminal Summary and Family Jurisdictions (Ministry of Justice,

Wellington, New Zealand, July 2009); New Zealand Law Commission, Dispute Resolution in the Family

Court Report 82 (Wellington, New Zealand, 2003); M. Barrett-Morris, M. Aujla and H. Landerkin, The Self-

Represented Litigant in the Courts: An Annotated Bibliography (Royal Roads University, 2004); M.

Stratton, Alberta self-represented litigants mapping project – Final Report (Canadian Forum on Civil

Justice, Edmonton, Alberta, 2007); Canadian Forum on Civil Justice, Alberta Legal Services Mapping

Project, An Overview of Findings from the Eleven Judicial Districts Final Report (Canadian Forum on Civil

Justice, Edmonton, Alberta, 2011).

13

R. Hunter, A. Genovese, A. Chrzanowski and C. Morris, The changing face of litigation: unrepresented

litigants in the Family Court of Australia (Research Report) (Law and Justice Foundation, August 2002);

Hunter et al found that there was an increase in SRLs in first instance matters, but that numbers of SRLs

on appeal remained consistent for the period of the study for the years 1995–1999.

14

J. Dewar, B. Smith and C. Banks, Litigants in Person in the Family Court of Australia – Research Report

No 20 (Family Court of Australia, Canberra, 2000), 11–12. See also Victorian Law Reform Commission,

Civil Justice Review: Report (Victorian Law Reform Commission, Melbourne, 2008), 564.

15

Family Law Council, Litigants in Person: A Report to the Attorney-General (Family Law Council,

Canberra, August 2000).

6 Self Represented Litigants –The Dark Side

of legal aid. 16 Changes to particular legislation over time may give rise to increases in

litigation in particular areas, a proportion of which will be instigated or defended by

SRLs. 17 Cultural changes may also have led to an increase in SRLs, with self-help and

internet resources more widely accessible, coupled with an emerging ‘do-it-yourself’

culture. 18

Many attempts have been made to support SRLs in Australian and overseas

jurisdictions. The development of more focused legal assistance programs (such as

QPILCH 19), educational resources for judicial officers (discussed further below), the

establishment of court-based programs and information sessions and the

development of SRL-specific materials 20, have all contributed to support for ‘do-it-

yourself’ approaches as well as to mitigating the impact on court resources. However,

understanding of SRL's needs is not universal and in any jurisdiction specific SRL

supports may or may not be available to, or adequate for the needs of, all SRLs.

Judicial officers and court staff report that many SRLs may approach litigation using a

‘Google it’ approach, with limited success or effectiveness.

Perceptions About SRLs

Although SRLs are often consigned to one homogenous (largely problematic) group 21

and it is assumed that they place a strain on the civil justice system, 22 there is little

evidence to support this view and many instances of positive accounts about SRLs. 23

In court publications, for example, there is evidence of a cultural shift towards

recognising SRLs as a legitimate client group that courts need to accommodate. 24

However, the perception that these litigants pose a problem for courts is widespread.

This gives rise to assumptions about SRLs common in most literature and in journal

and other articles, including that SRLs:

require more court time; 24

are more likely to require a hearing; 25 and

16

R. Hunter, J. Giddings and A. Chrzanowski, Legal Aid and Self-Representation in the Family Court of

Australia (Griffith University, May 2003).

17

For example, changes to Part VII the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) led to an increase in residence and

contact orders: see Family Law Council, Litigants in Person: A Report to the Attorney-General (Family Law

Council, Canberra, August 2000)), 13.

18

M. Hawkins, Emerging Trends in the Provision of Legal Services: Some Australian Experiences (Speech

presented to the Commonwealth Law Association Conference, Nairobi, 7 September 2007).

19

See http://www.qpilch.org.au/ (accessed 19 March 2014)).

20

See the extensive work in Canada at http://www.representing-yourself.com/ (accessed 19 March

2014)

21

Australian Institute of Judicial Administration and the Federal Court of Australia, Forum on Self-

Represented Litigants (Sydney, 17 September 2004).

22

D. Webb, ‘The right not to have a lawyer’ (2007) 16 Journal of Judicial Administration 165–178.

23

D. Webb, ‘The right not to have a lawyer’ (2007) 16 Journal of Judicial Administration 165–178.

24

Family Court of Australia, Self-represented litigants: A challenge – Project Report December 2000–

December 2002 (Family Court of Australia, 2003). Many Australian courts have developed Litigants in

Person plans and improved information and processes for SRLs.

24

Federal Magistrate’s Court of Australia, Annual Report 2003–2004 (Federal Magistrate’s Court of

Australia, Canberra, 2004).

25

Federal Magistrate’s Court of Australia, Annual Report 2003–2004 (Federal Magistrate’s Court of

Australia, Canberra, 2004).

Self -Represented Litigants –The Dark Side 7

THE DILEMMAS POSED BY

SELF-REPRESENTED LITIGANTS

– THE DARK SIDE

increase costs for all parties due to a need for more pre-trial proceedings,

poor issue identification, greater time responding to unclear and

irrelevant evidence and more time spent in hearings. 26

Despite these reports, recent research in the United Kingdom suggests that SRLs with

difficult behaviours are a ‘very small minority’, 25 at least in the lower courts.

It seems likely, and some court decisions report this, that there is a small number of

SRLs who require more court time and are difficult to deal with and that this

population may be greater in higher courts. These SRLs may be difficult to deal with

because of personality disorders and behavioural factors, which may mean that a

particular SRL is more likely to be in dispute and less likely to act in a rational, logical

or helpful manner. It is also possible that some SRLs may initially engage in litigation

in a rational way, however, repeated interactions with other litigants and with the

litigation system may in fact affect the physical and mental health of the SRL, making

it less likely they can continue to engage in a positive, constructive or rational way in

other court-related interactions. 26

Courts indicate that they may have repeated interactions and long-lasting

connections, often over years or decades, with some SRLs who might be regarded as

‘obsessive’. There is evidence that some SRLs will launch multiple actions across many

jurisdictions and appeal most if not all of the decisions made in respect of the

litigation they are involved in. Attempts to control these SRLs through a declaration

that they are ‘vexatious’ can be difficult, time consuming and onerous for those

involved in making the applications. The typical legislative frameworks mean that

there are few cases where such proceedings are taken. 27

In addition sometimes the behaviour can be difficult or problematic but it may not be

‘vexatious’ (or cannot yet be defined in that way) in that the proceedings may not be

‘untenable’ or may lack some other quality. 28 In addition, Australian case law relating

to vexatious declaration suggests that the process is time consuming and difficult in

26

Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, Review of the criminal and civil justice system in

Western Australia – Final Report Project 92 (Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, 1999), 153.

25

See R. Moorhead and M. Sefton, M. Litigants in person. Unrepresented litigants in first instance

proceedings (Department for Constitutional Affairs Research Series 2/05, England & Wales), 2005),

available at http://www.familieslink.co.uk/download/july07/DCA%20view%20of%20LIPs.pdf (accessed 19

March 2014)).

26

See, for example, G. M. Grant. and D. M., Studdert, ‘Poisoned chalice? A critical analysis of the

evidence linking personal injury compensation processes with adverse health outcomes,outcomes’

(2009) 33(3) Melbourne University Law Review 865–885. On litigation neurosis, see F. Campbell,

‘Litigation Neurosis: Pathological responses or rational subversion’ (2006) 26(1) Disability Studies

Quarterly, available at http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/655/832 (accessed 5 April 2014).

27

See Mr R. Clark, Attorney-General, ‘Second Reading Speech Vexatious Proceedings Bill Bill’ in

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) (Parliament of Victoria, Melbourne, 2014), 371, available at

http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/images/stories/daily-

hansard/Assembly_2014/Assembly_Daily_Extract_Wednesday_19_February_2014_from_Book_2.pdf.

28

See Kowalski v MMAL Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1069 at [44]; Ramsey v Skyring

(1999) 164 ALR 378 at [51]. See also Soden v Kowalski [2011] FCA 318 “For practical purposes, the test

of whether a proceeding is vexatious is whether it is, in Roden J’s words, “so obviously untenable or

manifestly groundless as to be utterly hopeless”.”

8 Self Represented Litigants –The Dark Side

that judges may need to spend a considerable amount of time reviewing complex fact

and legal issues.

In the UK, some limited attention has been paid to this ‘difficult and obsessive’

group, particularly in the appellate area. Decisions dealing with obsessive litigants

include Bhamjee v Forsdick (No 1) 29 and Bhamjee v Forsdick (No 2). 30

In a UK report 31 that was more focused on lower courts, the Master of the Rolls

stated:

There has been a significant increase of obsessive litigants determined

to have no procedural stone unturned, regardless of whether they have

any arguable ground of appeal. Nearly 40% of all who apply for

permission to appeal are litigants in person, of whom only one tenth

can demonstrate that they have arguable grounds of appeal. Yet each of

them is entitled to an oral permission hearing. Each hearing takes about

half an hour.

In addition to this the two Deputy Masters of the court have to spend

about two hours each day on utterly unproductive Registry work:

determining and dealing with appellants notices which the court has no

jurisdiction to entertain, dealing with groundless applications under

Taylor v Lawrence which are flooding in at the rate of 200 a year and

dealing with correspondence relating to defective applications. Four

officers man the relevant section in the Civil Appeals Office. They handle

matters which take up an inordinate amount of the court’s time for very

little advantage.

Further reform of our procedure is required to ensure that our energies

can be directed to providing justice for those who have a valid claim on

our services.

The dimensions of the issue are difficult to determine; however, the same UK

Research Report noted that such litigants could be described as ‘difficult’ and/or

obsessive and that ‘vexatious’ was not a term that could be usefully applied:

There are three main species of behaviour which, although not

uncommonly found in the same litigant, can individually or collectively

lead to the judgment that a litigant is difficult or obsessive:

• The making of far fetched or totally meritless claims;

• The making of repeated claims (or applications within cases)

of a similar type and/or against the same or similar litigants

(re litigation or harassment of individuals);

• Behaving in an abusive and/or uncooperative manner.

29

Bhamjee v Forsdick (No 1) [2003] EWCA Civ 799.

30

Bhamjee v Forsdick (No 2) [2003] EWCA Civ 1113.

31

See R. Moorhead and M. Sefton, Litigants in person. Unrepresented litigants in first instance proceedings

(Department for Constitutional Affairs Research Series 2/05, England & Wales), 2005), available at

http://www.familieslink.co.uk/download/july07/DCA%20view%20of%20LIPs.pdf (accessed 19 March

2014)).

Self -Represented Litigants –The Dark Side 9

THE DILEMMAS POSED BY

SELF-REPRESENTED LITIGANTS

– THE DARK SIDE

Vexatious litigant is a term of legal art and for that reason we avoid

using the term here, though such litigants usually have to have indulged

repeatedly in the inappropriate issuing of claims or applications.

Within the legal system, principles of fairness, legitimacy and efficiency require that

court and tribunal processes are conducted fairly, and many judicial officers indicate

that this minority group of SRLs makes it difficult to conduct processes in these cases,

in a fair manner. It has been suggested that the Australian legal system itself is ill-

equipped to deal with SRLs and is an alienating environment for many. This literature

suggests that much of the Australian litigation system is based on professionalism,

and many SRLs could find themselves at a disadvantage to adequately understand

court procedures, rules of court, the language of the law and to represent their cases

in court. 32

It remains unclear what proportion of SRLs are disadvantaged because the legal

system is poorly designed to accommodate SRLs or whether the difficulties arise as a

result of the attributes of the litigants themselves. 33 For example, as previously noted,

there is proportion of SRLs who successfully navigate the court system relying on their

own resources. A further group may do quite well with only minimal coordination and

navigation assistance from the court. However either explanation may hide a smaller

group that distorts the system to the detriment of those whom they oppose in court

actions and consumes more court time and more resources. In Canada, this small

group has been called ’celebrity’ SRLs 34 –They may often be the focus of judicial and

court concern although they may represent only a tiny proportion of the SRL

population.

Impacts on the Judiciary

When dealing with SRLs, judicial officers may be required to spend more time

conducting a hearing and may face more uncertainty as well as differing and often

higher levels of judicial involvement and commitment. 35 For example, in the context

of the judicial engagement required, although a judge is the impartial arbiter in the

system in which Australian courts operate, the judge may need to depart from this

role when dealing with SRLs. Recent discussion relating to this topic suggests that

when a judge deals with an SRL they may need to apply ‘substantive impartiality’, that

is, adjudicators need to engage with SRLs and ensure they are informed about their

32

D. Webb, ‘The right not to have a lawyer’ (2007) 16 Journal of Judicial Administration 165–178.

33

Lord Woolf, Access to Justice: Interim Report to the Lord Chancellor on the Civil Justice System in

England and Wales (HMSO, London, June 1995), 119; D. Webb, ‘The right not to have a lawyer’ (2007) 16

Journal of Judicial Administration 165–178.

34

J. MacFarlane, ‘Self-Represented Litigants in Family Law’, Paper presented at ABA Conference, Miami,

3 April 2014.

35

See E. Richardson, Self-represented parties: A trial management guide for the judiciary (County Court

of Victoria, Melbourne, 2004). Case duration is likely to be longer in most cases where the SRL is

‘difficult and/ or obsessive and this is the most reported impact on the judiciary. Where the SRL is

inactive, cases may be shorter than average. However, a just outcome does not seem to be related to

SRL activity.

10 Self Represented Litigants –The Dark Side

rights, procedural options and the possible detriment they may face. 36 This approach

will necessarily take more time than a hearing process where representatives can be

relied upon to support litigants and provide external explanations.

However, the extent to which judges depart from processes that are used when

dealing with represented litigants or the impact of more difficult SRL behaviour is not

well understood and there are clear and significant differences between different

courts, registries and jurisdictions partly because some are better able to refer to

support agencies or supportive material and processes. 37

There are other issues that can arise with SRLs and make it difficult for a ‘fair’ hearing

to be conducted. For example, a party opposing an SRL or a witness for that party may

be required to undergo cross-examination by an SRL, which may be traumatic in some

instances. 38 In addition, the party opposing the SRL may expend or incur more legal

costs as a result of delays or time taken at trial by the SRL, 39 and may be more likely to

feel a sense of injustice and may be left feeling aggrieved with the court process

because of the assistance provided to the SRL. 40

These issues may be magnified where obsessive or difficult behaviour is present and

where the SRL is using the hearing process as a means to cause harm to the other

party and potentially causing additional cost with limited court supervision.

In such circumstances, it is also more likely that a judicial officer will be required to

spend time explaining court procedures, rules of evidence and issue identification.

They may need to spend more time crafting judgements that reduce opportunities for

further litigation. Court staff may be required to perform more work in explaining

processes and assisting with filling out and lodging of court forms. 41 In addition,

working with SRLs can increase the pressure on the judicial officer to ensure justice is

served through the provision of assistance and information, 42 and this impact can be

magnified where difficult or obsessive behaviour is present and where judicial stress

may be a reality. 43

36

See M. Flaherty, ‘Self-litigants and Represented Litigants: A Sea Change in Adjudication’, in P. Oliver

and G. Mayeda (eds), Principles and Pragmatism: Essays in Honour of Louise Charron (LexisNexis, 2014),

Ottawa Faculty of Law Working Paper No. 2013-07 (October 2013), available at

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2348708 (accessed on 19 March 2014).

37

R. Hunter, Family Law Case Profiles, (Justice Research Centre, Law Foundation of New South Wales,

Sydney, June 1999.).

38

Family Law Council, Litigants in Person: A Report to the Attorney-General (Family Law Council,

Canberra, August 2000); Law Council of Australia, Erosion of Legal Representation in the Australian

Justice System Research Report (February 2004).

39

Family Law Council, Litigants in Person: A Report to the Attorney-General (Family Law Council,

Canberra, August 2000).

40

Law Council of Australia, Erosion of Legal Representation in the Australian Justice System Research

Report (February 2004).

41

Family Law Council, Litigants in Person: A Report to the Attorney-General (Family Law Council,

Canberra, August 2000). Note Court staff may inadvertently extend time for further lodgements without

understanding the cost implications or the previous record of the applicant.

42

Law Council of Australia, Erosion of Legal Representation in the Australian Justice System Research

Report (February 2004).

43

J. Dewar, B. Smith and C. Banks, Litigants in Person in the Family Court of Australia – Research Report

No 20 (Family Court of Australia, Canberra, 2000).

Self -Represented Litigants –The Dark Side 11

THE DILEMMAS POSED BY

SELF-REPRESENTED LITIGANTS

– THE DARK SIDE

Techniques Available to the Judiciary

There is some material about judicial interventions and approaches that judges can

use to assist those SRLs described as ‘obsessive’ and ‘difficult’. In some jurisdictions,

much can be done outside the courtroom to provide support and ‘link in’ with other

services to promote earlier resolution and understanding of processes and outcomes.

For example, there are many examples of problem-solving courts where judges are

actively involved in ensuring that an SRL understands and can refer litigants to

external services. Such interventions can be useful where alcohol and substance

abuse is an issue and also to ensure that follow-up reporting and management take

place. 44 Therapeutic justice is oriented towards using integrated approaches to focus

on improving the well-being and mental health of those with legal issues and

supporting the interpersonal skills of lawyers, judges and others.

In addition, in some cases it may be that Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) can

assist at least in narrowing issues or with planning and this can assist the judiciary as

SRLs are better prepared to discuss issues and concerns. However, routinely, in many

jurisdictions, SRLs are not referred to ADR (which can be coupled with unbundled

legal or related services to support decision-making). While ADR may not necessarily

result in complete resolution, it can be coupled with conflict coaching and dispute

management interventions that can assist litigants to focus on long-term interests

and goals.

There may be specific behavioural interventions that can assist. 45 Although there is

material that suggests that there is some evidence to show that therapeutic

approaches are ineffective unless used in tandem with cognitive therapy focusing on

consequences rather than the rights and wrongs of the issue, 46 there is a wealth of

literature suggesting that careful attention to procedural justice and therapeutic

interventions can support SRLs. In addition, in the mental health court area, there is

work that suggests that those with mental health problems can experience

improvement in their symptoms and health if court interactions support procedural

justice. 47

Procedural justice in this context requires that the litigant’s ‘voice’ is heard and that

there is an emphasis on respectful, courteous communication and on dignity. Some

44

Videos and supportive documentation relating to techniques used in court through the

Neighbourhood Justice Centre initiatives area available at

http://www.civiljustice.info/do/search/?q=NJC&start=0&context=2785725 (accessed 4 April 2014).are

available at http://www.neighbourhoodjustice.vic.gov.au/. See also http://www.civiljustice.info/njc/

(accessed 8 April 2014).

45

See B. Eddy, High conflict people in legal disputes (HCI Press, 2009.).

46

PaulP. E. Mullen and GrantG. Lester, ‘Vexatious Litigants andUnusually PersistentComplainantsand

Unusually Persistent Complainants and Petitioners: From Querulous ParanoiatoParanoia to Querulous

BehaviourBehav.Behaviour’ (2006) 24 Behav. Sci. Law 333–349.

47

K. A. Beijersbergen, A. J. Dirkzwager, V. I. Eichelsheim, P. H. van der Laan and P.

Nieuwbeerta, (accessed 5 April 2014)Procedural justice and prisoners’ mental health problems:

A longitudinal study (2013) Crim Behav Ment Health, available at

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24009140 (accessed 5 April 2014).

12 Self Represented Litigants –The Dark Side

studies report that judicial interactions that take place with respect and dignity affect

litigants in that they may be more likely to perceive the court as ‘legitimate’ and more

likely to consider that the goals expressed by the court are also their own. 48

Other judicial intervention options can include clearly breaking the dispute into issues

and ‘hearing’ the issues. In addition, judicial officers can:

provide preliminary explanations of the process and use these as a

reference point. There is extensive research about procedural justice and

what can support positive engagements in court and explanations

supporting positive perceptions about procedural justice. 51 There is also

a wealth of research that shows that procedural explanation can reduce

stress and anxiety and that this effect may be more significant where

mental illness or high-conflict behaviour is present. 49

adopt and use particular communication techniques – to model, where

appropriate, responses that demonstrate empathy, attention and

respect. 50

support short adjournments, encourage SRL list making (which can

promote more rational behaviour), and early issue identification with

visual cues and printed resource and other materials.impose firm overall

time limits that set expectations while noting that a propensity to argue

about the fairness of deadlines may ensue. Where obsessive behaviour is

present there may be a greater need to set guidelines and limits as the

SRL may have difficulty imposing what may appear to be rational limits

on their own behaviour. Overall, the approaches used will require

cohesive court wide approaches and training of court staff.

Communications with the court should be managed and protocols should

be in place and published to deter inappropriate behaviour and contact. 51

join the SRL in problem-solving about resolution of the case, encourage

positive approaches while pointing out the legal consequences and

constraints.

indicate to the representative for the other side the extent of assistance

that will be offered to the SRL and ask for feedback before providing that

48

See H. W. Wales, V. A. Hiday and B. Ray, ‘Procedural justice and the mental health court judge’s role in

reducing recidivism’ (2010) International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, available at

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.06.009. See also http://big.assets.huffingtonpost.com/gtown.pdf.

51

See T. Sourdin and A. Zariski (eds), The Multi-Tasking Judge (Thomson Reuters, Sydney. 2013) and in

particular Chapters 2, 3 and 4.

49

See T Sourdin and A Zariski (eds), The Multi Tasking Judge (2013, Thomson Reuters) and in particular

Chapters 2, 3 and 4.

50

See B. Eddy, High conflict people in legal disputes, (HCI Press, 2009.).

51

Justice E. Kyrou, ‘Litigants in Person’, Paper presented at the Managing People in Court Conference,

National judicial College, Canberra, 10 February 2013, available at http://njca.com.au/wp-

content/uploads/2013/07/Justice-Kyrou-.pdf.

Self -Represented Litigants –The Dark Side 13

THE DILEMMAS POSED BY

SELF-REPRESENTED LITIGANTS

– THE DARK SIDE

assistance to maintain a perception of fair treatment for the other

parties. Brief standardised checklists may be helpful 52

Importantly, judicial interventions need to be coupled with consistent messages and

processes across courts. Cost disincentives in the context of difficult behaviour may

also need to be carefully considered so that cost sanctions occur quickly and are

closely related in time to the instances of behaviour that lead to the cost order being

made. Current cost sanction approaches employed by Judges within existing

arrangements may not operate as a disincentive if not sufficiently proximate in time

to an event.

Conclusion

The challenges posed by SRLs have resulted in numerous programming and policy

responses within Australian courts at both the state and federal levels. These

responses include increased assistance and written information for SRLs (for example,

the outreach services provided at the Administrative Appeals Tribunal), development

of self-help services (including internet-based resources, online and off-line videos),

legal advice services, 55 education specifically targeting at judicial skills, 53 bench books

for judicial officers and the commissioning of a small number of studies on the impact

of SRLs. 54 Legal aid funding has been supported for certain types of hearings, 55 and

pro bono service support is also a feature of some courts and tribunals and supported

by legal clinic work.

Many court and tribunal services have been adapted to support SRLs and some

tribunals and courts increasingly cater to this group of litigants. However despite this

work, it is clear that some SRLs are not supported adequately and require more

support if they are to pursue legal rights. In addition, some SRLs may be treated

differently from other represented litigants and this may not necessarily be

advantageous or helpful. For example, although many matters involving SRLs are

resolved prior to hearing, it is not known how many settle with the assistance of an

ADR process and whether cases involving SRLs may settle ‘later’ because ADR is not

always available for this cohort. In some courts and tribunals, SRLs are specifically

excluded from ADR programs.

52

Justice E. Kyrou, ‘Litigants in Person’, Paper presented at the Managing People in Court Conference,

National judicial College, Canberra, 10 February 2013, 47, available at http://njca.com.au/wp-

content/uploads/2013/07/Justice-Kyrou-.pdf.

55

An example is the Self-Representation Civil Law Service (SRCLS) in Queensland. The SRCLS is modelled

on the Citizens Advice Bureau, which operates in the Royal Courts of Justice in London.

53

As with the Judicial College of Victoria from 2011 to 2014.

54

The extent to which these various initiatives have assisted SRLs or courts in dealing with SRLs is not

known: see, for example, Victorian Law Reform Commission, Civil Justice Review: Report (Victorian Law

Reform Commission, Melbourne, 2008), 564, regarding a discussion on the impact on pro-bono schemes.

See also M. Dye, An Evaluation of Services for Self-Represented Litigants in the Federal Magistrate’s

Court (Federal Magistrate’s Court of Australia, Canberra, October 2004) for a discussion of the various

materials and services provided to SRLs and whether SRLs found them helpful.

55

Family Court of Australia, Self-represented litigants: A challenge – Project Report December 2000–

December 2002 (Family Court of Australia, 2003).

14 Self Represented Litigants –The Dark Side

Initial screening and triaging of cases could be introduced as a preliminary step in

court processes, and all parties could be given the opportunity to be involved in ADR

processes that could be oriented towards case management and greater issue

identification. New technology solutions may be adapted such as telephone and

video-conferencing if screening indicates these or other approaches might be

appropriate. In addition, information, DIY and technology supports must become

commonplace in the court system, and with difficult and obsessive litigants, specialist,

‘joined-up’ services and case management meetings may assist to meet underlying

needs and provide more supportive frameworks.

For those SRLs that pose particular issues in terms of their obsessive and difficult

behaviours, it is critical to determine the extent, nature and impact of these

behaviours. A reliable database on the instance of SRLs in Australian courts is

required, together with demographic information and a new categorisation that

reflects the adverse impacts of these behaviours. Measuring these categories will

enable new and tested strategies to be targeted where they are needed most.

Possible categories could recognise more readily those who have been referred to

other services, those who have not, those who raise safety or related issues, those

who are declared vexatious and those who have a number of actions (including in

other jurisdictions -to determine whether more holistic cross-jurisdictional responses

could assist).

Securing strong interfaces with support agencies, technological innovation that can

help to support, inform, manage and monitor (and may build more ‘ownership’) as

well as better survey data about how justice systems are working from the SRL

perspective will all serve to improve the overall SRL experiences, assist with future

system design issues and assist to ensure that effective processes are in place for

those SRLs who may have more difficult and obsessive behaviours.

Self -Represented Litigants –The Dark Side 15

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Understanding Abdominal TraumaДокумент10 страницUnderstanding Abdominal TraumaArmin NiebresОценок пока нет

- EB - Lecture 2 - ECommerce Revenue Models - HДокумент8 страницEB - Lecture 2 - ECommerce Revenue Models - HXolani MpilaОценок пока нет

- Grade 2 - PAN-ASSESSMENT-TOOLДокумент5 страницGrade 2 - PAN-ASSESSMENT-TOOLMaestro Varix100% (4)

- Zsoka PDFДокумент13 страницZsoka PDFMasliana SahadОценок пока нет

- Information BulletinДокумент1 страницаInformation BulletinMahmudur RahmanОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Manajemen IndonesiaДокумент20 страницJurnal Manajemen IndonesiaThoriq MОценок пока нет

- Khandelwal Intern ReportДокумент64 страницыKhandelwal Intern ReporttusgОценок пока нет

- Office of The Court Administrator v. de GuzmanДокумент7 страницOffice of The Court Administrator v. de GuzmanJon Joshua FalconeОценок пока нет

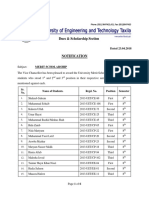

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationДокумент6 страницDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDОценок пока нет

- Centre's Letter To States On DigiLockerДокумент21 страницаCentre's Letter To States On DigiLockerNDTVОценок пока нет

- City Government of San Juan: Business Permits and License OfficeДокумент3 страницыCity Government of San Juan: Business Permits and License Officeaihr.campОценок пока нет

- Safety Moment Manual LiftingДокумент1 страницаSafety Moment Manual LiftingEvert W. VanderBerg100% (1)

- Kepler's Law 600 Years Before KeplerДокумент7 страницKepler's Law 600 Years Before KeplerJoe NahhasОценок пока нет

- IOT Liquid Level Monitoring SystemДокумент5 страницIOT Liquid Level Monitoring SystemNegmОценок пока нет

- Arcmap and PythonДокумент29 страницArcmap and PythonMiguel AngelОценок пока нет

- Julian's GodsДокумент162 страницыJulian's Godsअरविन्द पथिक100% (6)

- MAY-2006 International Business Paper - Mumbai UniversityДокумент2 страницыMAY-2006 International Business Paper - Mumbai UniversityMAHENDRA SHIVAJI DHENAKОценок пока нет

- Kargil Untold StoriesДокумент214 страницKargil Untold StoriesSONALI KUMARIОценок пока нет

- Common Application FormДокумент5 страницCommon Application FormKiranchand SamantarayОценок пока нет

- Intentional Replantation TechniquesДокумент8 страницIntentional Replantation Techniquessoho1303Оценок пока нет

- Chemistry Sample Paper 2021-22Документ16 страницChemistry Sample Paper 2021-22sarthak MongaОценок пока нет

- Alphabet Bean BagsДокумент3 страницыAlphabet Bean Bagsapi-347621730Оценок пока нет

- Platform Tests Forj Udging Quality of MilkДокумент10 страницPlatform Tests Forj Udging Quality of MilkAbubaker IbrahimОценок пока нет

- Category Theory For Programmers by Bartosz MilewskiДокумент565 страницCategory Theory For Programmers by Bartosz MilewskiJohn DowОценок пока нет

- GravimetryДокумент27 страницGravimetrykawadechetan356Оценок пока нет

- Solar Presentation – University of Texas Chem. EngineeringДокумент67 страницSolar Presentation – University of Texas Chem. EngineeringMardi RahardjoОценок пока нет

- Your Porsche CodeДокумент10 страницYour Porsche Codemahmut ezikОценок пока нет

- GPAOДокумент2 страницыGPAOZakariaChardoudiОценок пока нет

- Network Profiling Using FlowДокумент75 страницNetwork Profiling Using FlowSoftware Engineering Institute PublicationsОценок пока нет

- Simptww S-1105Документ3 страницыSimptww S-1105Vijay RajaindranОценок пока нет