Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tata Ace Story

Загружено:

Manav ManochaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tata Ace Story

Загружено:

Manav ManochaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Tata Ace was a small four-wheeled commercial vehicle launched by Tata Motors in

May 2005 at a price of 225,000 rupees (Rs.) ($5,000)1 with a payload capacity of 0.75 tons2

The Ace cost 50% less than any other four-wheeled commercial vehicle in India and was

significantly cheaper than pickup trucks with similar payload capacities found in

international markets. Unlike other commercial vehicles, the Ace, with its compact size

and shorter turning radius, could maneuver through India’s narrow urban streets and

cost-effectively transport small loads to villages and towns in rural areas.

By offering a niche vehicle that met the unique needs of the Indian transportation sector

at a price comparable with that of a three wheeler, the Ace created an entirely new

product category

The annual target of 30,000 vehicles was sold in less than a year, despite the product’s

being available in only approximately 25% of the country.

India had a nonmotorized- vehicle sector that included

bullock carts, bicycle rickshaws, horse-drawn carriages, and

manual pull carts. The size of this nonmotorized segment was

large but undocumented.

By world standards, India’s road network in 2006 was

considered to be inadequate and underdeveloped. While India

had 3.32 million kilometers of roads, only 2% were national

highways and only 12% of this 2% were four lanes (two lanes

in each direction) or more.12 Within urban areas, particularly

near commercial and retail markets, roads were very narrow

and congested. Traffic was further exacerbated by the lack of

adherence to traffic rules and the presence of multiple vehicle

types, pedestrians, and animals on the road. Road conditions

often prevented trucks from reaching retail markets, and final

goods delivery had to be completed via three wheelers, bullock

carts, or human labor. These delivery methods often resulted

in damaged goods, longer lead times, and shrinkage.

In 2001,18 Tata Motors posted a loss of Rs. 5 billion ($111 million), which was the largest

loss in the history of any Tata company and the largest loss ever recorded for any

private-sector company in India. This was due to cyclical downturn in the commercial-

vehicle segment and an economic recession.

Kant, head of Tata Motors’s Commercial Vehicle Division, and other executives realized

that the company would need to take drastic measures and outlined three focus areas:

cost reduction, quality improvement, and new-product introduction

The company realized that its core business could be

threatened by the absence of larger (greater than 45-ton) and

smaller (sub two-ton) vehicles in its product portfolio. The

smaller commercial vehicle would also be attractive to Tata

Motors in light of the financial loss of 2001, since smaller-

commercial-vehicle demand was historically less cyclical than

that of medium or large vehicles.

The Ace team was also the first at Tata Motors to implement cross-functional teams for

product development as well as the first to make extensive use of the production

preparation process (3P).

Wagh’s task would be further complicated by the strict cost controls for the project. The

total development budget was not to exceed Rs. 2.2 billion ($49 million). For

comparison, the budget for Tata Motors’s Indica was Rs. 17 billion ($378 million),

The Ace was conceived as a product “from the customer, for the customer.”

Interviewees were looking for a vehicle that offered the price, fuel efficiency, and

maneuverability of a three wheeler but with the safety, durability, additional payload,

and comfort of a four-wheeled truck. Ideally, the customer wanted a scaled-down

version of Tata’s four-ton 407 truck.

Market research suggested that being a three-wheeler driver was not a desirable

occupation.

With three wheelers selling in a price range of Rs. 100,000 to

Rs. 200,000 ($2,222 to $4,444), the team set a price target of Rs.

200,000 ($4,444) for the Ace. Above this level, market research

suggested that demand would fall off precipitously.

Combining this price target with the budgetary restrictions

would make designing the Ace even more challenging and

force the team to think creatively to create a product that

offered trucklike features at the contemplated price point.

One way the transportation market could be segmented was based on the functional

needs of different customers.

The Ace’s core market would be customers looking to

transport 750 to 1,500 kilograms over a distance of 100 to 200

kilometers. Based on this target market as well as the

opportunity to grow the total market pie, the team estimated

that 45% of the Ace’s customer base would come from people

planning to purchase three wheelers, 15% from potential

pickup and light-commercial-vehicle purchasers, and 40%

from first-time commercial-vehicle purchasers.

Within the functional market segment above, one could

further segment customers into four groups (estimated percent

of the market): performance sensitive (7%), balanced

perspective (25%), return-on-investment (ROI) sensitive (55%),

and acquisition price constrained (13%) (see Exhibit 5).

The Ace team faced three major challenges in creating a

vehicle that met customer needs and the price target.

Overloading capability As part of its market research,

the team conducted tests to see how three-wheeled vehicles

were being used in the field. Based on these results, the team

created a “duty cycle” that represented the aggregate

hypothetical usage for the vehicle (see Exhibit 7 for duty-cycle

data). Average tonnage and speeds were measured. The data

suggested that the vehicle would be overloaded, since quick

acceleration was not of prime importance on India’s slow-

moving roads and speed considerations were outweighed by

the desire to reduce the per unit cost of transportation through

large loads. As a result, the team focused on how to design a

product that could withstand the strain of overloading. Using a

computer-aided design (CAD) prototyping system, the design

team, guided by R. R. Akarte, vice president of the Engineering

Research Center, was able to rapidly iterate and isolate stress

points. By limiting the use of higher-strength steel to just these

stress points, the team was able to ensure a lower-cost yet

durable design. Overloading considerations also determined

the selection of a rigid front-axle design and rear-wheel drive.

While most Indian vehicles, including three wheelers, offered

body-on-frame construction (the cabin was a separate structure

and bolted to the frame), the Ace would offer a

semimonocoque body that would provide the ride quality of a

car or Japanese minitruck but prevent the cracks that typically

resulted when monocoque vehicles were overloaded.

Engine selection Customers had indicated a preference

for a diesel-engined vehicle due to the fuel’s greater efficiency

and lower per gallon cost in India. One option would be to

offer a one- cylinder engine similar to that found in a three

wheeler. However, this engine would not be powerful enough

for the contemplated payloads and desired speed and would

also fail in meeting the stringent emissions and noise,

vibration, and harshness (NVH) targets for four wheelers. At

the other end of the spectrum, the company considered

sourcing a four-cylinder diesel engine from a multinational

company. Using an existing engine would save time and

would already be proven in the field. However, even the

smallest foreign-made engines were 40–50 horsepower, which

was more than twice the level needed in the Ace, as well as

double the cost target.

Under the guidance of Akarte and P.M. Telang, president of

Light and Small Commercial Vehicles, A.V. Lakshmi Pati, a

veteran in engine design and development, created an

innovative two- cylinder diesel engine concept based on the

Indica passenger car’s four-cylinder engine. Costs would be

minimized due to parts sharing, and the performance levels

would be just right for the vehicle. The team then altered this

engine to fix the excessive noise and vibration levels and

worked with a supplier to develop a rotary fuel-injection

pump that could meet emissions standards without electronic

systems, thereby reducing costs and after-sales service

complexity.

Safety, comfort, and aesthetic considerations Early in

the design process, the team decided that the Ace should meet

the higher M1/N1 class safety norms instead of the less

stringent quadricycle norms on which most of the European

minitrucks were based. Since the Ace would be a Tata-brand

vehicle, it was decided early on that it should conform to the

highest safety standards. Furthermore, if Tata Motors could

offer a safer product to the consumer, the Indian government

would have no reason to adopt the quadricycle norms for its

highways and could take a positive step in vehicle-safety

standards.

The most straightforward way to meet these safety norms

would be to design a vehicle with a semiforward face (engine

in front of the cabin akin to a passenger car). However, market

research indicated that customers preferred a flat-face vehicle

that looked more like a large commercial vehicle and allowed a

greater percentage of the length of the vehicle to be used for

goods transport without “wasted” space. The engineering

team used crash-test computer simulations and developed a

cabin that met full-frontal-crash requirements while still

maintaining a flat-faced stance. In addition, the front

windshield was pasted to the steel window frame instead of

attached using a rubber seal so that it could add structural

strength.

Through a process called aggregate outsourcing, Tata

Motors would source the entire rear axle, frame, and

front axle from third parties instead of assembling these

modules in-house from outsourced parts

The team also leveraged the power of the Internet by

making the Ace the first Tata Motors product to

extensively use e-sourcing with its suppliers.

In order to control costs, the team decided to manufacture

the Ace at an existing underutilized Tata Motors plant in the

western city of Pune. Locating in Pune would also allow the

Ace to tap into Tata Motors’s existing vendor base and save on

outbound freight costs, since it was estimated that 70% of the

demand for the Ace would come from the western and

southern states of India. The entire Ace production line would

be built within the existing commercial-vehicle plant.

Through creative design, using existing facilities and

aggregate outsourcing, the team was able to meet the Rs. 2.2

billion ($49 million) budget.

Based on these rational and emotional considerations,

the marketing team developed a few key messages that it

believed would resonate with customers. The Ace would

be advertised as “India’s first minitruck.”

The team decided that the Ace rollout should be conducted

in phases beginning with five states in the western and

southern parts of India. These regions were selected because

market research suggested they were regions where three-

wheeler demand was strongest.

Based on this data, the company developed a new

dealership format called 1S (3S was the traditional

dealership that offered sales, service, and spares). The

dealership would only be responsible for sales and

included a 400-square-foot building, one or two vehicles,

plus a desk and a phone (no additional vehicle inventory

would be on the premises).

In order to avoid the cost of providing service bays at

its dealerships, the company created a program called

“Suvidham,” which means “convenience” in Hindi.

Through this program, Tata Motors trained existing rural

mechanics free of charge on how to complete simple

maintenance procedures on the Ace. In addition, each

mechanic received a free set of tools and a sign to display

at their garage. The company also launched a “mobile

workshop” that would travel to small villages and

construction sites on a predetermined schedule to

provide spare parts and lubricants to mechanics and

customers.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Steel Structure ErectionДокумент33 страницыSteel Structure ErectionAhmed ImranОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Road Signs in JapanДокумент7 страницRoad Signs in JapanMicha100% (5)

- Parts Book: TR35 Off-Highway TruckДокумент348 страницParts Book: TR35 Off-Highway TruckMartinezОценок пока нет

- Manual Tractor Comet 3 - 08F023948 - eДокумент88 страницManual Tractor Comet 3 - 08F023948 - eTina Manz100% (1)

- Manual de Utilizare Case Ih 956 XL 1 TransДокумент204 страницыManual de Utilizare Case Ih 956 XL 1 TransArpad Szollosi80% (5)

- Sterling Cargo Workshop ManualДокумент20 страницSterling Cargo Workshop Manualcharles97% (35)

- Cat Forklift Gp30 Schematic Service Operation Maintenance ManualДокумент27 страницCat Forklift Gp30 Schematic Service Operation Maintenance Manualfrankstewart270488qny99% (77)

- Mindex vs. MorilloДокумент2 страницыMindex vs. MorilloRiva Mae CometaОценок пока нет

- TMNДокумент37 страницTMNManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- H2S FatalityДокумент3 страницыH2S FatalityAhmedAmer1Оценок пока нет

- Manav Manocha,: Nmims M - HCL T - S & M - CДокумент2 страницыManav Manocha,: Nmims M - HCL T - S & M - CManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- Operation ProjectsДокумент4 страницыOperation ProjectsManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- Ice-Cold Refrigerator: Financial Data ($1000s) Capital AvailableДокумент3 страницыIce-Cold Refrigerator: Financial Data ($1000s) Capital AvailableManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- Notes - Social Media LaunchДокумент2 страницыNotes - Social Media LaunchManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- Advertising Media Planning: A PrimerДокумент29 страницAdvertising Media Planning: A PrimerManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- NMIMS - SBM: Teaching Plan Financial Management Academic Year: 2017-18 Course Code Course Title Course Instructor/sДокумент3 страницыNMIMS - SBM: Teaching Plan Financial Management Academic Year: 2017-18 Course Code Course Title Course Instructor/sManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- Corporate Social Responsibility - PolicyДокумент5 страницCorporate Social Responsibility - PolicyManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- Amn Asnd Asd Kjasn Djkasndiubaszkjbihzbjbijjbksd Sdjhbjhasdanb AsjkjaДокумент1 страницаAmn Asnd Asd Kjasn Djkasndiubaszkjbihzbjbijjbksd Sdjhbjhasdanb AsjkjaManav ManochaОценок пока нет

- Poulin Pro PP208EPS24L Snowblower Owners ManualДокумент40 страницPoulin Pro PP208EPS24L Snowblower Owners ManualMelОценок пока нет

- 3118 TP Tipper TruckДокумент2 страницы3118 TP Tipper TruckYernena NareshОценок пока нет

- 1109 KW 1,487 HP: Gross HorsepowerДокумент12 страниц1109 KW 1,487 HP: Gross HorsepowerGino Chavez ValenciaОценок пока нет

- Kerax 380.34 6x4 HD LeДокумент5 страницKerax 380.34 6x4 HD LeIlvan AlvandiОценок пока нет

- Procedures For Excavation, Pipe Laying & Jointing - Mechanical Engineering Notes & Pipe Laying ProceduresДокумент15 страницProcedures For Excavation, Pipe Laying & Jointing - Mechanical Engineering Notes & Pipe Laying ProceduresPasubulaОценок пока нет

- Material Handler: 91,040 Lbs. (41 295 KG) Operating WeightДокумент4 страницыMaterial Handler: 91,040 Lbs. (41 295 KG) Operating WeightBart JohnОценок пока нет

- Dannmar: Sx-6/Xl User ManualДокумент36 страницDannmar: Sx-6/Xl User Manuallalit PatilОценок пока нет

- Law in PhilippinesДокумент2 страницыLaw in PhilippinesSterling CañeteОценок пока нет

- KF760 Touring Usage GuideДокумент12 страницKF760 Touring Usage GuideLeo PortillaОценок пока нет

- Economic Viability Report For Industrial Mining License-Category BДокумент8 страницEconomic Viability Report For Industrial Mining License-Category Bnadula2008Оценок пока нет

- Azzurro Aug PetroserveДокумент1 страницаAzzurro Aug PetroserveKalpesh MistryОценок пока нет

- 310E Articulated Dump Truck PIN 1DW310EX F677827 708124 IntroductionДокумент6 страниц310E Articulated Dump Truck PIN 1DW310EX F677827 708124 IntroductionNelson Andrade VelasquezОценок пока нет

- 03 FaqДокумент3 страницы03 FaqjobesmindОценок пока нет

- Спецификации toyota-bt-reflex-rre140 rre160Документ4 страницыСпецификации toyota-bt-reflex-rre140 rre160YakupovmmОценок пока нет

- DSB 2 Technical-DataДокумент2 страницыDSB 2 Technical-DataY.EbadiОценок пока нет

- TB43-0147 Color, Markings and Camouflage 1975Документ163 страницыTB43-0147 Color, Markings and Camouflage 1975dieudecafe100% (2)

- 5 1 Mine Dump Truck Wheel Spindle REMANДокумент2 страницы5 1 Mine Dump Truck Wheel Spindle REMANSACHIDHANANDHAM AОценок пока нет

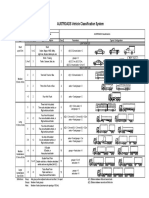

- AUSTROADS Vehicle Classification System: Level 1 Level 3 Level 2Документ1 страницаAUSTROADS Vehicle Classification System: Level 1 Level 3 Level 2zeipoibjasОценок пока нет

- MIlitarised Truck MAN - TG SeriesДокумент24 страницыMIlitarised Truck MAN - TG Seriesraja Ali100% (1)

- Minetruck MT436B: Underground Articulated Truck With 32.6-Metric Tonne Load CapacityДокумент5 страницMinetruck MT436B: Underground Articulated Truck With 32.6-Metric Tonne Load CapacityДмитрий ПодвигинОценок пока нет

- EU Pocketbook 2023/2024Документ48 страницEU Pocketbook 2023/2024The International Council on Clean TransportationОценок пока нет