Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nerves 2

Загружено:

KS0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

7 просмотров3 страницыОригинальное название

nerves2.txt

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

TXT, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате TXT, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

7 просмотров3 страницыNerves 2

Загружено:

KSАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате TXT, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 3

The answer is D, nervous tissue.

So we'll start at a gross anatomical level,

and we won't actually see these parts of the nervous system in the gross anatomy

lab, but they are things that you could see.

Beginning at a gross anatomical level, the nervous system

consists of the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system.

So it's the peripheral nerves that we'll be seeing, but a lot of this module

is to give you the context for understanding the nerve

pathways that you'll actually see when we get to the cases.

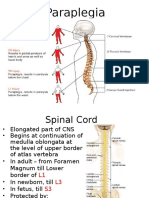

The central nervous system includes the brain and the spinal cord.

These are tender and delicate structures, and both of them,

both parts of the central nervous system,

are surrounded by bony cavities.

The brain is enclosed by the cranial cavity.

The spinal cord lies within the vertebral canal surrounded

by the spine, which consists of vertebrate and intervertebral disks.

When we're born, our vertebral column and our spinal cord

are approximately the same length.

As we grow, the vertebral column grows much faster than the spinal cord.

The spinal cord stops growing in childhood.

The result of this disparity in growth is

that the spinal cord is shorter in the adult

then the vertebral canal that surrounds it.

Also surrounding the central nervous system within the bony housing

are three meningeal membranes.

The closest to the central nervous system,

actually resting right on the surface, is the pia mater.

So the pia mater, which is right on the surface of the central nervous system,

means the dear mother.

So she's closely embracing the central nervous system.

The arachnoid mater lies outside the pia mater, and this the spidery mother.

You can actually see on the surface of the central nervous system

the spidery appearance of the arachnoid.

Between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater

is a space which contains the cerebrospinal fluid.

Cerebrospinal fluid is circulating throughout the brain

and through the central canal of the spinal cord,

and then entering the sub-arachnoid space.

It's continuously flowing, it's continuously circulating,

and in addition to providing metabolic support for the brain and spinal cord,

it also forms a nice hydraulic cushion which

can protect the central nervous system in case of trauma.

The outermost layer of the three meningeal membranes

is the dura mater, which means the tough or enduring mother.

This is the thickest of the layers.

This is dense connective tissue.

It's adherent to the skull, but not adherent to the vertebrae.

So this is the space if you require anesthesia

for either a surgical procedure or during childbirth,

anesthetic can be injected into the space between the dura

and the vertebrae, and that's an epidural anesthetic.

If a sample of cerebrospinal fluid needs to be withdrawn,

it can be taken from the sub-arachnoid space

between the arachnoid and the pia.

And as you'll see in a minute, the ending of the spinal cord

well above the ending of the vertebral canal

provides a useful space where needles can enter the vertebral canal

without injuring the spinal cord itself.

The two divisions of the central nervous system

are the brain and the spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system

is basically anything that leaves the central nervous system

and travels throughout the body.

There are two broad categories of peripheral nervous system,

cranial nerves and spinal nerves.

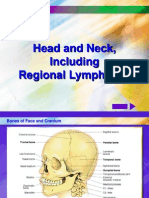

There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves.

Those leave the brain and travel across the cranial cavity,

through the meninges, taking layers of meninges with them,

and leaving the skull through small passages.

The 12 cranial nerves are supplying structures in the head primarily,

and they're numbered from 1 to 12, beginning with the olfactory nerve.

In addition to the cranial nerves, there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves.

The vertebral column consists of seven cervical vertebrae,

12 thoracic vertebrae, five lumbar vertebrae, five fused sacral vertebrae,

and a variable number of coccygeal vertebrae,

somewhere between three and five.

The spinal nerves, part of the peripheral nervous system,

leave the vertebral canal between pairs of individual vertebrae.

So eight cervical nerves leave between either the cervical vertebrae

or cervical vertebrae and the skull.

The thoracic nerves leave between the thoracic vertebrae, lumbar nerves

between the lumbar vertebrae, and the sacral nerves

come out through holes on both the anterior

and posterior surfaces of the sacrum.

There is usually one pair of coccygeal nerves, and they're small

and they don't do very much.

If we look now, instead of an en face view, an interior view

of the central nervous system at an axial section through it,

you can see right here is the formation of the spinal nerve,

and then just as it's leaving at the intervertebral foramema,

it divides into a relatively large ventral ramus and a relatively small

dorsal ramus.

A ramus means a branch, and so the ventral ramus

will supply most of the body wall and the limbs.

The dorsal ramus will supply the skin and muscles and sensation

from the bones of a stripe down the back of the head and down the back itself.

It's kind of like a skunk stripe extending from the head

down to the end of the sacrum.

All the dorsal primary rami have a segmental pattern of enervation.

They distribute like the stripes on the shirt that you can see in this diagram.

The dorsal rami will supply the central portion

of the back in a segmental fashion.

The ventral primary rami will do the same thing in the front.

So the trunk, including the back, will be supplied both sensation and motor

enervation by segmental nerves that run around in stripes.

There's some overlap in the sensory enervation of these regions.

In contrast, the limbs and structures in the neck are supplied through plexuses.

There are three major spinal nerve plexuses.

The cervical plexus is cervical spinal nerves that combine to form a network,

and the branches leaving the plexus will have

contributions from more than one spinal nerve.

It's basically a backup plan.

Instead of relying on input from just one spinal nerve,

they receive contributions from more than one spinal nerve.

The second plexus, one of the two that will be the most important to us,

is the brachial plexus.

As you know from the earlier introduction, the brachium is the arm,

and so the brachial plexus will be a combination of spinal nerves

that come together, form a network, exchange fibers, and then supply

the upper limb.

Again, then we have segmental enervation over the trunk.

For the lower limb, the lumbar and sacral nerves

will come together to form the lumbosacral plexus.

Same principle again.

Spinal nerves will enter the plexus, exchange fibers, and the nerves

leaving the plexus will have input from more than one spinal nerve.

So again, if there were an injury at a particular segment of the spinal cord,

there would still be contributions from other spinal nerves

that might make up for that.

So for your review question, all of the following statements are true except.

Вам также может понравиться

- Exams To Confirm and Negate Spinal Spondy and StenoДокумент5 страницExams To Confirm and Negate Spinal Spondy and StenoKSОценок пока нет

- Assist Tech by GRP Midterms ReportingДокумент10 страницAssist Tech by GRP Midterms ReportingKSОценок пока нет

- Reviewer in General Biology Ii - KmbsДокумент5 страницReviewer in General Biology Ii - KmbsKSОценок пока нет

- The Skeletal System: Elaine N. MariebДокумент87 страницThe Skeletal System: Elaine N. MariebKSОценок пока нет

- Mother To Son PoemДокумент3 страницыMother To Son PoemKSОценок пока нет

- The LotteryДокумент9 страницThe LotteryKSОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- 2020.03.10 AddendumДокумент2 страницы2020.03.10 AddendumStib BrionesОценок пока нет

- Dr. Tiago ScopelДокумент19 страницDr. Tiago ScopelDr. Tiago ScopelОценок пока нет

- UrinalysisДокумент32 страницыUrinalysiskholoud220Оценок пока нет

- F3 3.2Документ41 страницаF3 3.2amalina rohaizanОценок пока нет

- Antihuman Globulin (Ahg) TestДокумент38 страницAntihuman Globulin (Ahg) TestJerome ValerianoОценок пока нет

- Recent Advances in The Pathophysiology of Psoriasis: Dr. Mikhin George ThomasДокумент72 страницыRecent Advances in The Pathophysiology of Psoriasis: Dr. Mikhin George ThomasYudi FadilahОценок пока нет

- Thyroid 2Документ58 страницThyroid 2Seff CausapinОценок пока нет

- MarsiiДокумент35 страницMarsiiMariel Magtalas100% (1)

- Stretching: Mechanisms and Benefits For Sport Performance and Injury PreventionДокумент19 страницStretching: Mechanisms and Benefits For Sport Performance and Injury PreventionGeorge M. PamborisОценок пока нет

- Tooth Discolour at Ion PedoДокумент28 страницTooth Discolour at Ion PedoFourthMolar.comОценок пока нет

- Anatomy 1.1 Anatomy in MotionДокумент5 страницAnatomy 1.1 Anatomy in Motionlovelots1234100% (2)

- Dental Anatomy & Occlusion NOTESДокумент7 страницDental Anatomy & Occlusion NOTESyosman1000100% (1)

- Understanding Transfusion Reactions in Oncology by NurseДокумент6 страницUnderstanding Transfusion Reactions in Oncology by NursefitriОценок пока нет

- Mandibular Buccal Bifurcation Cyst: Case Report and Literature ReviewДокумент5 страницMandibular Buccal Bifurcation Cyst: Case Report and Literature Reviewboooow92Оценок пока нет

- RossДокумент436 страницRossAna Ion100% (1)

- Kumar: Robbins Basic Pathology, 9th EditionДокумент4 страницыKumar: Robbins Basic Pathology, 9th EditionAmar AlkhafajiОценок пока нет

- Quadri HeliceДокумент12 страницQuadri HeliceMartin AdriazolaОценок пока нет

- Dewi Maya S (P160 Hanifah Ambang F (P16025) Nurul Yuniartanti (P160 Roni Setyawan (P16043) Wildan Aulia A (P160Документ5 страницDewi Maya S (P160 Hanifah Ambang F (P16025) Nurul Yuniartanti (P160 Roni Setyawan (P16043) Wildan Aulia A (P160hanifa ambОценок пока нет

- Head & Neck A&pДокумент15 страницHead & Neck A&pJSeashark100% (6)

- KunyazaДокумент6 страницKunyazakaranjamm100% (9)

- ParaplegiaДокумент51 страницаParaplegiaChuah Wei HongОценок пока нет

- Anatomy and Physiology of The Immune System, Part 1: Lessons From The Miracle DoctorsДокумент16 страницAnatomy and Physiology of The Immune System, Part 1: Lessons From The Miracle DoctorsRhedge Asuncion-LittauaОценок пока нет

- Prepared By: Lyle Alexandra MondaresДокумент12 страницPrepared By: Lyle Alexandra MondaresLyle Alexandra MondaresОценок пока нет

- A Chimpanzee BrainДокумент21 страницаA Chimpanzee BrainKevin ChenОценок пока нет

- Jake C. Canapi, RN, MSN, Ph.D. Lily Ann C. Mallabo, RN, MSN Gail Ann Parel-Pascual, RMT Reymel B. Magora, RMTДокумент48 страницJake C. Canapi, RN, MSN, Ph.D. Lily Ann C. Mallabo, RN, MSN Gail Ann Parel-Pascual, RMT Reymel B. Magora, RMTAngelo LacisteОценок пока нет

- Pex 03 02Документ5 страницPex 03 02Jila Hafizi100% (1)

- The EyesДокумент9 страницThe EyesEmmanuel JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Medical Terminology 2Документ20 страницMedical Terminology 2khererer11Оценок пока нет

- The Temporomandibular Joint, Part II (Myofascial Techniques)Документ4 страницыThe Temporomandibular Joint, Part II (Myofascial Techniques)Advanced-Trainings.com100% (3)