Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Breastfeedin Works Kosmala

Загружено:

Elisa Maria WahyuniАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Breastfeedin Works Kosmala

Загружено:

Elisa Maria WahyuniАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Public Health | Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 183–191 | doi:10.

1093/pubmed/fdl012 | Advance Access Publication 22 July 2006

Breastfeeding works: the role of employers in supporting

women who wish to breastfeed and work in four

organizations in England

Joanna Kosmala-Anderson1, Louise M. Wallace2

1

Health Services Research Centre, CWG04, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry CV1 5FB, UK

2

Health Services Research Centre, GE404, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry CV1 5FB, UK

Address correspondence to Louise M. Wallace, E-mail: l.wallace@coventry.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

An important factor influencing duration of breastfeeding is mother’s employment status. The main aim of this study was to determine the experi-

ence and views of employees (n = 46) in four large public sector organizations concerning breastfeeding support at work. Participants were

recruited if they were employed by one of four public service employers and if they were planning to go on maternity leave in the next 6 months,

on maternity leave or within 6 months of return from maternity leave. They completed a questionnaire anonymously. Almost 80% of women

wanted to continue breastfeeding after returning to work. However, 90% of all respondents were not aware of any employer policy nor offered

any information concerning support to enable breastfeeding after returning to work, despite two organizations having a range of maternity- and

breastfeeding-related policies in development and some facilities in place. Almost 90% of respondents stated the employers should do more to

support breastfeeding. This should include providing pregnant staff with information about breastfeeding support that they should expect and

could therefore plan to use, including access to facilities to express and to store breast milk, to enable them to work flexible hours and to take rest

breaks during working hours. Recommendations are made for employers.

Keywords breastfeeding, emploment, infant feeding, infamt nutrition, maternal health

Introduction developing ovarian cancer, premenopausal breast cancer and

osteoporosis.6

The nutritional, immunological, psychological and economic

The early introduction of other foods is of public health

benefits of breastfeeding are well documented.1 Both

concern because it exposes infants to increased infection,

UNICEF and The World Health Organization2,3 recom-

particularly diarrhoeal diseases. In some cultures, it may lead

mend mothers should breastfeed exclusively for at least 6

to poorer infant nutrition and adversely affect growth rates.7

months. However, the full benefits of breastfeeding will not be

As work can be essential to economic survival for some famil-

realized if breastfeeding is curtailed by unsupportive employ-

ies, it is likely that work will take precedence over breastfeed-

ment practices. We report on a survey of the employees of

ing, leading to early introduction of artificial food and early

four public sector organizations in England and the recom-

weaning. Of interest to employers, however, is likely to be the

mendations made to address the deficiencies which may have

impact on staff absence resulting from higher rates of respira-

benefits to mothers and babies and to their employers.

tory, ear and gastrointestinal infections, often a cause of child-

There are important differences in health outcomes between

hood illness and maternal work absence.8 Potentially, enabling

those mothers and babies who breastfeed and those who artifi-

female employees to breastfeed when they return to work

cially feed.4 Babies who are breastfed are less likely than for-

could impact on absenteeism. Employers may also benefit

mula-fed babies to suffer from constipation or diarrhoea5 and

from retaining skilled female employees, who may consider

also are less prone to childhood diseases including juvenile

returning to work rather than leaving, if they are enabled to

diabetes, allergies, asthma, eczema, gastrointestinal, urinary

and respiratory tract infections. They are less likely to be

obese and have high blood pressure later in life.5 Breast-

Joanna Kosmala-Anderson, Research Fellow in Psychology

feeding also confers health advantages on the mother by

Louise M. Wallace, Professor of Psychology and Health, Director Health Services

helping her regain her figure and long-term reduction of risks of Research Centre

© The Author 2006, Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Faculty of Public Health. All rights reserved. 183

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

184 JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

continue breastfeeding when they work.9 Therefore, it is in the 94.1% breastfeeding, supported by opportunities to feed

interest of mothers, babies and employers that mothers are their child in breaks or while at work.17 Such flexible work

enabled to continue to breastfeed when they return to work. practices are generally not available in developed countries.

Yet, there is evidence from surveys of breastfeeding duration While allowing more flexibility in organizing the total hours

that employment status and associated employment practices worked and shortening the hours worked in the immediate

may adversely impact on breastfeeding duration. The UK period after return to work are obvious remedies open to most

national infant feeding survey10 found that 19% of those who employers, there are studies that describe the active health pro-

stopped breastfeeding by 4 months attributed this to the need to motion efforts of employers. It is suggested that women are

return to work, and it was the most often cited reason for cessa- more likely to continue to breastfeed after entering employ-

tion (19%) by those who breastfed but ceased between 4 and 6 ment when lactation rooms and breast pumps are available in

months (39%). A Scottish Infant Feeding Survey in 2002 found their workplace.8,21 Job-related stress may limit women’s ability

that 28% of new mothers stopped breastfeeding because of to express breast milk for an infant feeding.1 Cohen and Mrtek

returning to work.11 In a Spanish study by Escriba and col- describe the positive impact on breastfeeding of an employer

leagues, 32% of mothers attributed ‘occupational reasons’ as the providing lactation rooms and breast pumps as a part of sup-

cause of stopping breastfeeding.12 Similar results were obtained port programme, such that breastfeeding duration among

by Ong and colleagues in a study conducted in Singapore. Work- employees matched women who do not work.8 Approximately

ing mothers were significantly more likely to stop breastfeeding 75% of mothers who took part in their survey were able to

than non-working mothers, and they most often attributed this maintain breastfeeding for at least 6 months after returning to

to the need to work.13 In a survey conducted in Turkey by Ylmaz work. A more intensive prenatal, perinatal and postnatal pro-

and colleagues, the two most important influences on duration gramme is described by Cohen and Mrtek, as summarized in

of breastfeeding were conditions at work and maternal leave Table 1.22 Five Californian companies provided lactation sup-

period.14 Results from a study in Brazil show that duration of port including a preparatory class about breastfeeding,

exclusive breastfeeding was longer among women with support information to supervisors, access to a lactation consultant and

for breastfeeding at work and shorter for those working week- access to rooms and equipment for pumping and storage of

ends or shifts.15 A recent study of female military personnel in breast milk. Results showed that 97.5% of those enrolled initi-

the United States showed that similar rates of initiation were ated breastfeeding and 57.8% continued for at least 6 months,

achieved by active and non-active duty personnel, but signifi- whereas maternity leave was on average 2.8 months. A pro-

cantly more active duty mothers stopped breastfeeding at 4 gramme to support fathers is described by Cohen and others.23

months.16 However, a cross-sectional study in Kenya showed Ortiz and colleagues describe a lactation programme offered to

that among the lowest socioeconomic group of working women, five corporations, which shows the positive impact of lactation

nearly all breastfed (99%), and 89% of the higher socioeconomic support and the provision of equipment and facilities.24 How-

group breastfed, but shift patterns compared with fixed hours ever, in none of these workplace intervention studies are there

influenced exclusivity of breastfeeding.17 These results show that baseline data nor were there control groups, limiting the con-

the issue of continuing breastfeeding after returning to work is clusions that can be drawn (see Table 1).

important in different countries. See Table 1. The regulatory framework of each country provides a con-

A national survey of family growth conducted in the text for employers’ duties towards the health of pregnant and

United States in 1988 showed that one-quarter of women lactating workers and employees rights. See Table 2 for a

employed post-partum made attempts to breastfeed; how- description of legislation in countries comparable to the

ever, most gave it up about a month after their return to United Kingdom. In the United States, breastfeeding legisla-

work.18 Another influential factor is the availability of mater- tion has been enacted in over a half of the states.25 In three

nity leave. Several studies show that women who breastfed states (Connecticut, Illinois and Minnesota), it is mandatory

also had longer maternity leave in comparison with women for employers to provide reasonable work time breaks for

who formula fed from the beginning.19–21 For examp1e, expressing milk, and they must provide a suitable room in

mothers who breastfed had averaged 3.4 months of mater- proximity to the employee’s work area. By contrast, in the

nity leave, whereas those who formu1a fed averaged 2.3 United Kingdom, there is less legislative support to protect

months.19 The duration of breastfeeding is also influenced by women’s right to breastfeed after returning to work. Women

the duration and flexibility of employment.14,15 Women who have the right to facilities to express at work, to reasonable

were employed part-time achieved longer duration rates than work time breaks, facilities to express and store breast milk

those who worked full-time.19,20 In Nairobi, Kenya, mothers and to rest to maintain breast milk production. More

surveyed between 4 and 12 months postpartum achieved recently, direct benefits to breastfeeding may be enabled

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

BREASTFEEDING WOMEN WORKERS IN THE ENGLISH MIDLANDS 185

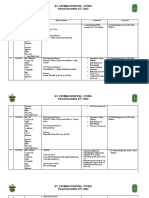

Table 1 The review of research regarding the relationship between duration of breastfeeding and support for breastfeeding at workplace

References Country Methods/sample Workplace intervention Results

Escriba et al.12 Spain 602 primiparous and None 32% of responding mothers report that they

secundiparous employed women stopped breastfeeding because of occupational

who delivered their babies in a reasons. The type of employment influences

large public hospital in Valencia. mother’s tendency to use her maternity leave:

Personal interviews were very few women employed in public sector

conducted in the hospital 2 days tend not to use their maternity leave (5%). This

after delivery figure increased among private sector (22%),

family businesses (55%) and domestic services

workers (51%)

Rea et al.15 Brazil Interviews of 69 factory workers None Duration of exclusive breastfeeding is longer

during pregnancy and after among women with support for breastfeeding

returning to work at work and shorter for those working

weekends or shifts

Lakati et al.17 Kenya Cross-sectional survey of 444 None Prevalence of breastfeeding was 94.1%, with

working mothers with infants aged lower social class 10% more likely to be

4–12 months breastfeeding. Logistic regression showed

mode of working (fixed versus shift hours) was

associated with exclusive breastfeeding at

1 month [odds ratio (OR) = 0.45 and at

2 months (OR = 0.39)]

Ylmaz et al.14 Turkey Descriptive study of 301 working None Two main factors influence duration of

mothers breastfeeding: conditions at work and

maternal leave period

Ong et al.13 Singapore Interviews of 2149 women who None Working mothers are significantly more likely

delivered in eight hospitals with to stop breastfeeding than non-working

obstetric services in Singapore mothers, citing need to return to work

conducted at 2 and 6 months

postpartum

Rischel and United States A sample of records of mothers None Significantly more active duty mothers stopped

Sweeney16 delivered of live births in three breastfeeding at 4 months, compared with

military facilities. 261 records were non-active duty mothers (P < 0.05)

examined in two facilities with a

lactation consultant and one

without, 6 months after birth

Intervention studies

Cohen and United States 187 female employees of Los Lactation program involved support Mothers who breastfed had averaged 3.4

Mrtek22 Angeles Department of Water and by a lactation professional during months of maternity leave, whereas those who

Power and Space Corporation three phases: prenatal, perinatal and formula fed from the beginning averaged 2.3

completed a questionnaire on return to work. During prenatal months. When lactation rooms and breast

regarding breastfeeding classes, issues of parenting, pumps are available at work, breastfeeding

behaviours. The duration was breastfeeding and support services duration among employees matches women

reported by a lactation professional available in the workplace were who do not work. Approximately 75% of

discussed. During the perinatal phase, mothers who took part in their survey were

a corporate lactation consultant was able to maintain breastfeeding for at least 6

available to women and her family. months after returning to work. Inflexible work

Two weeks before return to work, hours and restrictive policy regarding using

women were provided with electric breaks by employees are the organizational

breast pump, visited lactation room. barriers for breastfeeding. Emotional and

On return to work, lactation educational workplace support is related to

consultant was available to mothers longer breastfeeding duration while employed

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

186 JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Table 1. Continued

References Country Methods/sample Workplace intervention Results

Cohen et al.23 United States 128 male employees of Los Angeles The Fathering Program offered fathers Infants of fathers who participated in the

Department of Water and Power and their partners breastfeeding Fathering Program breastfed for average of 8

and their partners. 66% of female education classes, full individual months; 69% of the infants were still breastfed

partners were employed either full- lactation counselling for both parents at 6 months

time or part-time and breast pumps to use at home and

at work for mothers

Ortiz et al.24 United States Retrospective records of 462 Lactation program included a choice Breastfeeding was initiated by 97.5% of the

women employed in five of (i) class on benefits of participants, with 57.8% continuing for at

corporations breastfeeding, (ii) access to lactation least 6 months. Of the 435 (94.2%) who

counsellor by visit and phone call in returned to work after giving birth, 343

pregnancy and throughout return to (78.9%) attempted pumping milk at work, and

work while breastfeeding and 336 (98%) were successful. They expressed

(iii) facilities and equipment to pump milk in the workplace for a mean of 6.3

at work months The mean postnatal maternity leave

was 2.8 months. The proportion of women

who chose to pump at work was higher

among women who were salaried than among

those who were paid hourly wages (P < 0.01)

through longer maternity leave. The Parental Rights Act fourth was a local University. It was ascertained before the

200326 guarantees that all pregnant employees are able to study that all the four organizations were developing prac-

take 26 weeks of paid ordinary leave followed by 26 weeks of tices to support breastfeeding, but that explicit statements of

unpaid additional maternity leave (but only for employees employees’ rights and the availability of facilities were not yet

who worked for the employer for 26 weeks by the 15th week enshrined in formally adopted policies at the time of the sur-

before the baby is due). Fathers are entitled to 2 weeks of vey. The results of the survey would therefore inform the

paid paternity leave. This legislation also states that parents adoption of such policies.

of children aged under 6 can apply for flexible working hours

that can be refused only if there is a clear business reason.

However, it is unlikely these measures will impact on Procedure

breastfeeding if employees are unaware of their rights, and

Permission for access to staff was sought from each organi-

employers do not publicize policies to support breastfeeding.

zation. A senior member of staff in each organization under-

Within a health scrutiny review of health services to support

took to distribute the survey to eligible staff. These were

breastfeeding undertaken by two local government authorit-

employees in the Coventry City Council who expressed an

ies in England,27 a survey was undertaken of four large public

interest and staff in the other organizations (Coventry Uni-

sector organizations to determine the awareness, experience

versity, South Warwickshire Primary Care National Health

and views of relevant female employees and their partners.

Service Trust and South Warwickshire General Hospitals

The aims of the study were to determine (i) the awareness of

National Health Service Trust) who were planning to go on

employees of their legal rights, (ii) the awareness of employees of

maternity leave in the next 6 months, on maternity leave or

their employer’s policies, where these existed, (iii) the views and

within 6 months of return from maternity leave. Those on

experiences of employees in relation to the breastfeeding sup-

paternity leave were included on a similar basis.

port provided by their employers, and (iv) to make recommen-

dations for changes in the policy and practice of the four large

public sector organizations surveyed to support the public health

Results

goals of the health services of Coventry and Warwickshire.

Two of these organizations provide hospital and com- Characteristics of the sample

munity health care to mothers and infants, one was one of Forty-six employees completed the questionnaire. They were

the two local authorities conducting the health scrutiny, the employed by four organizations: Coventry Council (n = 19),

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

BREASTFEEDING WOMEN WORKERS IN THE ENGLISH MIDLANDS 187

Table 2 The comparison of US, Australia, Europe and UK legislation regarding support for breastfeeding after returning to work

Country Legislative act Regulations

Australia National Breastfeeding Strategy The issue of breastfeeding at work is left up to the women to discuss with the employer on

to encourage breastfeeding awareness individual basis. However, employers are encouraged to support breastfeeding women and

and increase breastfeeding rate (2000)24 offered benefits (family friendly workplace status) if they decide to do so

The Equal Opportunity for Women in Employer can support women who want to combine breastfeeding and work in the context

Workplace Act, 199924 of an equal opportunity program. Employers who wish to do so are advised to develop a

breastfeeding and workplace policy and make it known to all employees. They are also

encouraged to consider offering mothers flexible return to work options, discussing lactation

breaks, offering flexible working hours and providing lactation rooms

United States Labor Code, Part 3 of Division 2, 200122 In over a half of the 52 states, mothers have right to breastfeed anywhere they go. In

Connecticut, Illinois and Minnesota, employers are obligated to support breastfeeding

mothers; in other states, employers are encouraged to do so (by making strong statements to

consider this a health choice, giving employers an opportunity to advertize themselves as

‘mother or infant friendly’)

Where supporting breastfeeding mothers is mandatory, employers are required to provide

reasonable amounts of break time for expressing milk and provide a room or other location

(other than a toilet stall) in proximity to employee’s work area

United Kingdom Management of Health and Safety at As long as an employee is breastfeeding, the employer’s duty is to consider whether working

Work Regulations, 1999 and Employment conditions are a risk to mother’s or baby’s health. Protective measures include access to a

Rights Act, 200229,30 private room where women can breastfeed and/or express milk, use of clean refrigerator for

storing expressed milk and facilities for washing, sterilizing and storing receptacles, as well as

time-off to express or breastfeed. If the risk cannot be avoided, the employer is obligated to

offer alternative work with similar terms and conditions

Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Mothers who work nights can negotiate different shifts while breastfeeding. There is no time

Regulations, 199929 limit on breastfeeding duration

EU Council Directive 92/85/EEC29 applies Employer must provide ‘suitable facilities’ (conveniently located near to sanitary facilities and

only to mothers who work in public sector with place to lie down if women wish to do so) for breastfeeding mothers to rest

Parental Rights, 200329 If work affects employee’s breastfeeding, the employer is obligated to temporarily alter her

working conditions and/or hours or give her alternative work to protect breastfeeding

All pregnant employees are entitled to 26 weeks of paid ordinary maternity leave followed by

26 weeks of unpaid additional maternity leave (only for employees who worked for the

employer for 26 weeks by the 15th week before the baby is due). Fathers are entitled to 2

weeks of paid paternity leave

Both parents of children aged <6 years can apply for flexible working hours that can be

refused only if there is clear business reason

EU countries The Maternity Protection Convention, Sets minimum standards for workplace maternity protection that include 14 weeks of

2000 (No. 183)31 maternity leave, rights to workplace health protection for the women and the child, including

breastfeeding and paid breaks or reductions in working time to breastfeed her child

The Maternity Protection This recommends that the employer should avoid providing compulsory night work if it is

Recommendation, 2000 (No. 191)31 incompatible with pregnancy or breastfeeding and allow one or more nursing breaks or a

daily reduction of working hours so that a woman can continue breastfeeding when she

returns to work after maternity leave, when practicable

South Warwickshire PCT (n = 11), Coventry University (n = 9) the range 30–35 years, and 72% aged 30–40 years, 61% had edu-

and South Warwickshire General Hospitals NHS Trust (n = 7). cation after they reached 18 years, and 61% of the respondents

Two-thirds of the sample (n = 30) were part-time employed and had taken maternity leave in the past 5 years, 31 of 44 women

so may have been benefiting from some flexibility in employed (70.5%) were currently on maternity leave, one woman was

hours to suit family circumstances. The sample was predomi- about to go on maternity leave, and for the two males, this last

nantly white (n = 41), with only two males, with an age spectrum question did not apply. In data presented below, relevant data

quite typical of the postpartum population,10 with a median in for breastfeeding are reported for the 44 women.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

188 JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Information and facilities offered by the employer Factors influencing the decision about returning to

about the availability of breastfeeding support on work after having a baby

return to work Eleven (25%) of women respondents stated that the support

A workplace nursery was available to 17 (37%) of respond- offered by the employer regarding breastfeeding would be an

ents, but only 14 (31%) expressed interest in using it, and important factor when considering the decision about return-

only nine women (20.5%) would want to visit their babies ing to work after having a baby. This may be a lower rate than

there during work to breastfeed. This suggests that provision if the sample was exclusively of those women surveyed before

of facilities to support expression and storage and rest breaks returning to work, because by definition, many respondents

to maintain breastfeeding may be more important for most had already decided to return to work in this sample. One

mothers. respondent reported: ‘I felt pressured into returning early

Only 1 of 44 respondents reported being offered informa- from my first spell of maternity leave so was unable to feed

tion about the support that she might be offered to enable after that – it just wasn’t an option according to my boss. The

breastfeeding to continue after returning to work, and she nursery at the hospital is very expensive and so I’ve decided

reported that she obtained this through her work role as a not to return to work after this spell of maternity leave’.

midwife, not directly as an employee. She obtained informa- Thirty-five women (79.5%) regarded it as important to con-

tion about the benefits of breastfeeding and voluntary tinue to breastfeed on their return to work, for example: ‘I

groups such as National Childbirth Trust, La Leche League took eight months maternity leave and was able to breastfeed

and Maternity Alliance, rather than specific workplace pol- my babies for this long. Flexible working hours on return

icies or facilities available to all employees. She did, however, allowed me to continue one out of three feeds a day, either

report that she was offered a free loan of a breast pump for before work or on return home’. But some women reported

use at work and a milk storage flask usually available to they decided not to breastfeed to avoid anticipated problems

patients. on their return to work: ‘I would have breast fed if I had more

Only seven respondents (15.9%) were aware of facilities info and support, however, as none was given I chose to bot-

such as prebooked rooms, where mothers could express and tle feed as I felt it would be easier knowing I had to return to

store breast milk while at work, and only three (6.8%) had work’. Of greater concern is where health and safety issues for

used it. However, no participants, men included, were aware the mother as an employee arose that appeared to influence

of information about formula feeding from their employer her decision to breastfeed: ‘I was asked to work in [the] isola-

nor did they receive promotional literature through work. tion ward, so [I was] looking forward to it. [But] I had to

None of the respondents were made aware of arrangements wean my baby off the breastfeeding because I did not want to

to support flexible working hours or flexible working within introduce any infections which I may carry in my body to my

the working day to accommodate childcare and breastfeed- baby. I was/am very unhappy about it’.

ing nor information about breast pumps for home use. Just On considering whether to return to work, flexible hours

seven women (15.9%) were aware of some prebookable were considered important for 40 (90.7%) of respondents,

rooms in which they could express, and three made use of and 16 (36.4%) wanted breaks to express and store milk dur-

them, but comments reveal that these were mostly those ing the working day. For example: ‘I was keen to breastfeed

facilities that they found for themselves. One woman stated: each child which I did till they were 15 and 18 months. I

‘I used to sneak into my boss’s office and quickly express think because of this determination nothing would stand in

hoping nobody would come in’. my way. Practical things like finding space in a fridge to store

Some mentioned that if the facilities had been available, milk and of course a room where there was no school chil-

they would maintain breastfeeding after returning to work, dren was important. With my second child there was a new

for example: ‘I was not aware of this availability, this would Head teacher and she kindly gave me her office at lunch

have encouraged me to continue breastfeeding’. Three time. I carried on expressing’. A further 14 (31.8%) wanted

women mentioned finding the sole-designated room in the breaks to breastfeed the child directly, which required access

University by accident, for example: ‘Just because there is a to affordable and local childcare.

sign on the door where I walk by daily’. Some women who

decided to express breast milk at work had to do it in Awareness of workplace policies that support

unsuitable places and in stressful conditions: For example: breastfeeding by employees

‘I asked for somewhere to express milk, I was offered a toi- Only four (8.7%) of all respondents were aware of any work-

let cubicle or a shower room which didn’t have a lock on place policies related to breastfeeding, covering employer

the door’. and employees’ rights and duties.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

BREASTFEEDING WOMEN WORKERS IN THE ENGLISH MIDLANDS 189

Organizational support for breastfeeding to return to work – maternity pay does not last that long!;

Forty-one (91%) of all participants thought that their Babies [were] transferred to formula milk for 2/3 feeds on

employer should do more to support employees regarding return to work. [I] Did not fancy the idea of expressing at

breastfeeding. Some 38 (82.6%) believed this should include work’. Four respondents did not feel confident to express

information in advance of maternity/paternity leave about milk at work because of poor facilities, for example, ‘As the

how breastfeeding can be managed at work, for example, rooms offered to me to express milk were not private or

‘More information provided earlier on to ensure an informed were not suitable, this meant that I stopped breastfeeding/

choice’. Although some participants were very specific about offering expressed breast milk on my return to work. The

what they thought the employer should provide: ‘I don’t lack of facilities to express milk was the only reason that I

think it is the employer’s responsibility to provide informa- moved to formula milk for my daughter’. Another added...

tion/advice about benefits/practicalities of either breast or ‘My husband used to collect my milk in his lunch hour to

bottle feeding. There are plenty of other agencies who take it home to the fridge as there was no storage facilities

already do this. However, the availability of a bookable, pri- either’.

vate room and fridges for storage of breast milk would be

useful should women wish to express milk whilst at work’.

Discussion

Such facilities and equipment were welcomed by 34 (73.9%)

of all respondents. Health promotion information about the Limitations of this study

benefits of breastfeeding were welcomed by 22 (48%) of The sample was relatively small, although it does represent

all participants, but only seven out of all participants were over a half of the eligible employees in each organization,

interested in knowing about formula feeding and five according to the personnel departments’ figures. As the

were interested in the role fathers could take in supporting study was mainly concerned with breastfeeding, employees

breastfeeding. who did not intend to breastfeed may be under-represented,

although some questions such as those concerning childcare

The best and the worse aspect of experience of the were relevant to all. Generalization to the circumstances of

current employer that affected breastfeeding those employed in other organizations is not possible to

Thirty-one women respondents submitted their comments determine. However, a brief search of the web pages we were

on the best experience and 22 on the worst experience. The given access to by the personnel departments of three major

most often mentioned best experience was long maternity local private employers (e.g. an automotive manufacturer)

leave that enabled mothers to finish breastfeeding before showed no mention at all of breastfeeding on the employee

they came back to work, for example, from a healthcare welfare aspects of these sites. We have some foundation

employee: ‘Employer has shown no interest but I never therefore for believing the absence of policies may reflect

expected it! Just pleased that maternity leave has increased. absence of work site support for breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding [was] finished by [my] return to work after 6

months’. Six participants commented on the support from Main findings of this study

their employer (such as access to lactation rooms, breaks for The results show that despite the efforts of the four employ-

storing and expressing milk), and three participants men- ing organizations to develop general policies for mothers’

tioned flexible work hours after returning from maternity well-being and two of them having some facilities and breast-

leave, as the best experience affecting breastfeeding. feeding policies in development, forty-two participants

The most often mentioned worst experience, reported by (91%) were unaware of any support that might be offered to

21 women, was the apparent lack of interest, information enable breastfeeding after returning to work, yet this is

and support from their employer. For example, ‘I had to sort widely available to employers and the public.28-31 Those

out a lot of things myself – a room, fridge etc. Surprise was women who accessed bookable rooms and equipment largely

shown that I was planning to breastfeed for longer than six did so through their own efforts, and many experienced

months – I got the feeling that they expected me to only be unhealthy conditions in their use. Access to workplace child-

expressing at work for a couple of weeks until my son care was only available for a minority. But for three-quarters

reached 6 months. Women should be encouraged to breast- of the sample it was or would have been important to con-

feed for as long as they/baby wants!’ Four participants felt tinue breastfeeding after returning to work. It is clear that

pressured to come back to work early after having a baby. these employers are failing to meet their health and safety

For example, ‘It would have been ideal to have had a year off obligations and are indirectly hampering public health efforts

work to breastfeed the babies for this long – however, [I] had to improve the duration of breastfeeding.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

190 JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

What is already known on this topic Resources relevant to employers and employees in relation

The research reviewed above suggests that many women per- to breastfeeding and maternity rights and safety: http://

ceive work and the continuation of breastfeeding to be www.hse.gov.uk/pubns.

incompatible and that they have low expectations of support.

However, skilled lactation support and workplace policies can

References

enable many mothers to plan to breastfeed on return to work.

1 Barber-Madden R, Petschek MA, Pakter J. Breastfeeding and the

working mother: barriers and intervention strategies. J Public Health

What this study adds

Policy 1987;436:531–41.

In the UK public sector, there are many skill shortages in

2 UNICEF. UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative: Health Benefits of Breast

professional posts, so it may be of intrinsic interest to Feeding. http://www.babyfreindly.org.uk (2002).

employers to know that a lack of employer support was per-

3 WHO. The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding: Results of a WHO

ceived to be a major source of dissatisfaction and in some Systematic Review. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

cases a reason for leaving the employer after maternity leave. 4 Walker M. A fresh look at the risk of artificial infant feeding. J Hum

Also, some respondents stayed away from work longer than Lact 1993;9(2):97–107.

they would have wished because they anticipated poor 5 Lawrence R. Maternal and Child Health Information Bulletin: A Review of

support on their return. The survey shows that the required Medical Benefits and Contra-Indications to Breastfeeding in the United States.

support is within the grasp of most employers if they were to Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1997.

make their existing policies and practices better known, 6 Labbok M. Health sequelae of breastfeeding for mothers. Clin Perinatol

provide simple prebookable rooms and equipment and provide 1999;26(2):491–503.

active encouragement of breastfeeding as the norm. This may 7 Lakati A, Binns CW, Stevenson M. The effect of work status on

take leadership, because one respondent noted ‘It’s not {just} exclusive breastfeeding in Nairobi. Asia Pac J Public Health

2002;14:85–90.

the employer but the staff members which need educating!’

8 Cohen R, Mrtek MB, Mrtek RG. Comparison of maternal absen-

teeism and infant illness rate among breastfeeding and formula-

feeding women in two corporations. Am J Health Promot

Recommendations

1995;10(2):148–53.

(i) Employees should have access to information on sup- 9 Work and Family Unit. Combining Breastfeeding and Employment.

port that is offered by their employer, and by local organizations, Work and Family Unit Newsletter insert, April 1998.

to enable breastfeeding to continue after returning to work. 10 Hamlyn B, Brooker S, Oleininkova K et al. Infant Feeding 2000. London:

(ii) Suitable, comfortable and stress-free facilities to TSO, 2002.

express and store breast milk should be provided. 11 Support for Breastfeeding at Work. Guidance Note. Health and

(iii) More flexible arrangements in working within time at Safety Services. University of Paisley, Scotland, 2004.

work and in overall working hours are necessary to give 12 Escriba V, Colomer C, Mas R et al. Work conditions and the decision

to breastfeed in Spain. Health Promotion Int 1994;9(4):251–8.

mothers the opportunity to express breast milk or to breast-

feed their baby at local childcare facilities. 13 Ong G, Mabel Y, Li FL et al. Impact of working status on breastfeed-

ing in Singapore. Evidence from the National Breastfeeding Survey

Addressing these issues may benefit employees and 2001. Eur J Public Health 2005;15(4):424–30.

employers alike, at very low cost to the employer, and sup- 14 Ylmaz G, Gurakan B, Akgun S et al. Factors influencing breastfeeding

port local public health initiatives to improve breastfeeding for working mothers. Turk J Paediatr 2002;44(1):30–4.

rates. Research on a wider spectrum of organizations, includ- 15 Rea MF, Venancio SI, Batista LE et al. Determinants of the breast-

ing those operating with similar policies in different coun- feeding pattern among working women in Sao Paulo. J Hum Lact

1999;15(3):233–9.

tries, would help show how workplace welfare and health

promotion activities can improve breastfeeding, the com- 16 Rishel PEN, Sweeney P. Comparison of breastfeeding rates among

women delivering infants in military treatment facilities with and

pany and the local economy.

without lactation consultants. Mil Med 2005;170(5):435–8.

Resources relevant to expressing and storing breast milk:

17 Lakati A, Binns C, Stenson M. Breast-feeding and the working

http://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/pdfs/BFNExpress- mother in Naorobi. Public Health Nutr 2002;5(6):715–8.

ing&Storing.pdf; http://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/

18 Lindberg LD. Trends and relationship between breastfeeding and

pdfs/BreastfeedingAndReturningToWork.pdf. postpartum employment in the United States. Soc Biol

Resources relevant to maternity rights, flexible working 1996;43:191–202.

and other employment rights: http://www.workingfamiliies. 19 Duckett L. Maternal employment and breastfeeding. NAACOG’S

org.uk. Clin Issu Perinat Womens Health Nurs 1992;3:701–11.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

BREASTFEEDING WOMEN WORKERS IN THE ENGLISH MIDLANDS 191

20 Yocca Ch. Workplace support for lactating mothers: a study of the 26 Breastfeeding and Returning to Work. Off for a Good start. Published by

benefits provided by employers in the Hudson Wisconsin area. The Health Education Board for Scotland. http://www.hebs.scot.nhs.uk/

research paper. The Graduate College University of Wisconsin, topics/childhealth/index.htm (2003).

Stout, USA, 2000. 27 Wallace LM, Jardine J. A health scrutiny of services to support the

21 Katcher A, Lanese M. Breastfeeding by employed mothers: a reason- initiation and duration of breastfeeding in Coventry and Warwickshire.

able accommodation in work place. Pediatrics 1985;88:728–36. Coventry and Warwickshire Councils, England, 2006.

22 Cohen M, Mrtek M. The impact of two corporate lactation programs 28 Balancing Breastfeeding at Work – Important Information for Workplaces.

on the incidence and duration of breastfeeding by employed moth- Commonwealth of Australia. http://www.health.gov.au (2000).

ers. Am J Health Promot 1994;8:436–41. 29 A Guide for New and Expectant Mothers who Work. Published by Health

23 Cohen R, Lange L, Slusser W. A description of male – focused and Safety Executive. http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg373.pdf

breastfeeding promotion corporate lactation program. J Hum Lact (2005).

2002;18(1):61–5. 30 New and Expectant Mothers at Work. A Guide for Health Professionals.

24 Ortiz J, Mcgilligan K, Kelly P. Duration of breast milk expression Published by Health and Safety Executive. http://www.hse.gov.uk/

among working mothers enrolled in an employer-sponsored lacta- pubns/indg373hp.pdf (2003)

tion program. Pediatr Nurs 2004;30(2):111–9. 31 Paul J. Healthy Beginnings: Guidance on Safety Maternity at Work. Geneva:

25 Baldwin EN, Freidman KA. A Current Summary of Breastfeeding Legislation International Labour Organization. http://www.ilo.org/public/

in the U.S. http://www.lalecheleague.org (2005). english/protection/condtrav/pdf/wf-jp-04.pdf (2004)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article-abstract/28/3/183/1515898

by Airlangga University user

on 03 April 2018

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Antepartum HaemorrhageДокумент18 страницAntepartum HaemorrhageOjambo Flavia100% (1)

- 1.maternal and Child Health NursingДокумент33 страницы1.maternal and Child Health NursingBhie Bhie100% (1)

- Inspirational Birth StoriesДокумент377 страницInspirational Birth Storiescris_c3100% (4)

- Partograph DR OdofinДокумент61 страницаPartograph DR OdofinEkiran BabajideОценок пока нет

- IMPAC Tool for Making Pregnancy SaferДокумент16 страницIMPAC Tool for Making Pregnancy SaferLea Foy-os CapiliОценок пока нет

- Case Presentation On AphДокумент20 страницCase Presentation On AphDeepti Kukreti86% (14)

- Prenatal Factors Influencing Growth and Development of FetusДокумент15 страницPrenatal Factors Influencing Growth and Development of FetusSrd Rch100% (1)

- Diagnosing: BY Tiyas K Maternity-Child Nursng Department Airlangga UniversityДокумент25 страницDiagnosing: BY Tiyas K Maternity-Child Nursng Department Airlangga UniversityElisa Maria WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Resume DiagnosisДокумент4 страницыResume DiagnosisElisa Maria WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Emerging Diseases: Mers Cov Dan Ebola Virus: Agung Dwi Wahyu WidodoДокумент54 страницыEmerging Diseases: Mers Cov Dan Ebola Virus: Agung Dwi Wahyu WidodoElisa Maria WahyuniОценок пока нет

- MAP ShakeRecipes Flyer PDFДокумент1 страницаMAP ShakeRecipes Flyer PDFElisa Maria WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Elder Abuse Class Plan and Activities-1Документ2 страницыElder Abuse Class Plan and Activities-1Laila Turrohmah KurniawatiОценок пока нет

- Vancouver Citation Style GuideДокумент3 страницыVancouver Citation Style GuideElisa Maria WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Essay and Paragraph OrganizationДокумент31 страницаEssay and Paragraph OrganizationElisa Maria WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Harvard CompleteДокумент15 страницHarvard CompleteFahmi Muhammad AbdillahОценок пока нет

- Hypopituitarism: Cachexia Is Present. The Patient Has Muscle and Organ Wasting and Disruptions ofДокумент7 страницHypopituitarism: Cachexia Is Present. The Patient Has Muscle and Organ Wasting and Disruptions ofElisa Maria WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Society For Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #52: Diagnosis and Management of Fetal Growth RestrictionДокумент16 страницSociety For Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #52: Diagnosis and Management of Fetal Growth RestrictionRaul DoctoОценок пока нет

- Supervisor: Dr. Agus Thoriq, Spog DM: AkbarДокумент31 страницаSupervisor: Dr. Agus Thoriq, Spog DM: AkbarAkbar GazaliОценок пока нет

- Baby ScheduleДокумент1 страницаBaby ScheduleHenrique LeandroОценок пока нет

- Pengaruh Prenatal Gentle Yoga Dalam Menurunkan TinДокумент7 страницPengaruh Prenatal Gentle Yoga Dalam Menurunkan TinYuliОценок пока нет

- Intrauterine Growth Restriction IUGRДокумент8 страницIntrauterine Growth Restriction IUGRJyoti Prem UttamОценок пока нет

- PDF Ijwhr 106Документ6 страницPDF Ijwhr 106hendraОценок пока нет

- E-ISSN: 2347-8640 P-ISSN: 2454-2660, Issue JETIR, (JULY September 2016)Документ9 страницE-ISSN: 2347-8640 P-ISSN: 2454-2660, Issue JETIR, (JULY September 2016)VaishaliОценок пока нет

- 432 Exam 1: Topic 1Документ24 страницы432 Exam 1: Topic 1Stephanie SuruОценок пока нет

- Aau, Management Guideline On Gyn-ObsДокумент202 страницыAau, Management Guideline On Gyn-ObsNaol Abdi100% (10)

- Cesarean SectionДокумент14 страницCesarean Sectionمؤمن شطناويОценок пока нет

- Cord ProlapseДокумент16 страницCord ProlapseMike Evangelista100% (1)

- Ob-Gyn Practice Changers: Folic Acid, Omega-3s, Pre-eclampsia ManagementДокумент57 страницOb-Gyn Practice Changers: Folic Acid, Omega-3s, Pre-eclampsia ManagementVirginia AbalosОценок пока нет

- Acolher e Escutar o Silêncio: o Cuidado de Enfermagem Sob A Ótica Da Mulher Surda Durante A Gestação, Parto e PuerpérioДокумент7 страницAcolher e Escutar o Silêncio: o Cuidado de Enfermagem Sob A Ótica Da Mulher Surda Durante A Gestação, Parto e PuerpérioGiulia VianaОценок пока нет

- WW.05.21 Forceps Assisted Vaginal DeliveryДокумент3 страницыWW.05.21 Forceps Assisted Vaginal DeliveryLani Munawir Holis HolisОценок пока нет

- Antepartum BleedingДокумент7 страницAntepartum Bleedingbluecrush1Оценок пока нет

- Efektifitas Aromatherapy Uap Lavender Dan Pijat Oksitosin Terhadap Produksi Asi Pada Ibu NifasДокумент7 страницEfektifitas Aromatherapy Uap Lavender Dan Pijat Oksitosin Terhadap Produksi Asi Pada Ibu NifasBAnfalia Dina ClaudiaОценок пока нет

- Jo Roby Statement of HarmДокумент13 страницJo Roby Statement of HarmMichael_Lee_RobertsОценок пока нет

- 33219-Article Text-97197-1-10-20201204Документ6 страниц33219-Article Text-97197-1-10-20201204ZisuhОценок пока нет

- Difficult Labor (Dystocia) : Disproportion Between The Presenting Part of The Fetus and The Birth CanalДокумент9 страницDifficult Labor (Dystocia) : Disproportion Between The Presenting Part of The Fetus and The Birth CanalMohammad Hadi AlghuraifiОценок пока нет

- Maternal and Child Health Schemes in IndiaДокумент37 страницMaternal and Child Health Schemes in Indiasasmita nayakОценок пока нет

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education Part 1Документ10 страницStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education Part 1Sheilla Tania MarcelinaОценок пока нет

- Maternal and Child Nursing Practice Quiz #8Документ25 страницMaternal and Child Nursing Practice Quiz #8Ayeza DuaОценок пока нет

- Morning Report Fatimah Kamis, 1 Desember 2022Документ8 страницMorning Report Fatimah Kamis, 1 Desember 2022Kevin NoyaОценок пока нет