Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Three Areas of Concern For Art Criticism Instruction Theoretical and Research

Загружено:

emysamehОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Three Areas of Concern For Art Criticism Instruction Theoretical and Research

Загружено:

emysamehАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

National Art Education Association

Three Areas of Concern for Art Criticism Instruction: Theoretical and Research Foundations,

Sociological Relationships, and Teaching Methodologies

Author(s): Karen A. Hamblen

Source: Studies in Art Education, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Summer, 1986), pp. 163-173

Published by: National Art Education Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1320912 .

Accessed: 20/09/2013 05:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

National Art Education Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Studies in Art Education.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STUDIES in Art Education Copyright by the

A Journal of Issues and Research National Art Education Association

1986, 27 (4), 163-173

Three Areas of Concern for Art CriticismInstruction:

Theoreticaland ResearchFoundations, Sociological

Relationships, and Teaching Methodologies

Karen A. Hamblen

Louisiana State University

Despite current support in art education for an aesthetic education model, there has

been no consistent and widespread implementation of art criticism instruction. In

this paper, it is posited that research and foundational deficits, as these are revealed

in the literature, may be contributing factors. The need for the development of

theoretical and empirical frameworks and methods for implementation is suggested

by an investigation of the three following areas: (1) theoretical and research founda-

tions of art criticism, (2) sociological relationships, and (3) teaching methodologies.

Serious questions have been raised as to whether the traditional art program

concentrating primarily on studio production adequately develops aesthetic

discriminations, knowledge of art content, and analytical and evaluative skills

(Mittler, 1980). Increasingly, art educators are advocating an aesthetic model

that includes instruction in art history and art criticism in addition to studio

production. The use of an aesthetic education model by organizations such as

the Getty Center for Education and its use as the framework for numerous

state curriculum guidelines suggest that this is an auspicious time for the

widespread implementation of art criticism instruction. Such implementation

in the classroom is not occurring.

In addition to the much-expected and healthy debates on how art criticism

should be defined and approached (Geahigan, 1975; Nadaner, 1984), there are

basic conceptual and research deficits that, unless rectified, suggest that art

criticism instruction may remain peripheral in education.

Among the difficulties that might be ascribed to existing approaches is

the lack of an explicit foundation upon which to build critical

dialogue. .. Almost equally troublesome are theories and concepts that

constitute the ingredients of a foundation for criticism yet fail to provide

any correlative method for teachers or students of criticism to use.

(Lankford, 1984, p. 151)

The purpose of this paper is to examine three areas pertinent to art criticism

instruction: (1) theoretical and research foundations of art criticism, (2)

sociological relationships, and (3) teaching methodologies. It is proposed that

available literature in these areas needs to be analyzed and interpreted in rela-

tion to art criticism and that, where deficits occur, new theoretical and em-

pirical frameworks and methods for implementation should be developed.

Theoretical and Research Foundations of Art Criticism

The area of philosophical aesthetics provides the primary theoretical ra-

tionale for art criticism instruction. Art critical judgments are often based on

aesthetic criteria, and art critical procedures are linked to aesthetic theories

(Hamblen, in press; Mittler, 1982). Art criticism is, at its most basic, an ex-

ploration of the nature of art and aesthetic responses. By the same token,

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

164 KAREN A. HAMBLEN

through a reliance on aesthetic foundations, art criticism has inherited all the

controversy that seems to surround each and every aesthetic issue (Hamblen,

in press). Weitz (1962) argues that art is an open, contested concept inasmuch

as it eludes any stable definition or assurance of meaning that will command

consensus. "Aesthetic theory is a logically vain attempt to define what cannot

be defined, to state the necessary and sufficient properties, to conceive the

concept of art as closed when its very use reveals and demands openness" (p.

52).

Whether the focus of art criticism should be on making judgments, the ex-

tent to which the artist's intentions should or should not enter into one'e inter-

pretation, what constitutes artistic criteria, and other aesthetic issues, are cer-

tainly valuable concerns for art criticism instruction and deserve discussion.

Getting caught up in the intricacies of aesthetics can, however, easily divert at-

tention from pedagogical necessities. Granted, art criticism cannot exist

separate from aesthetic issues. When art criticism enters the classroom, other

concerns also develop, such as how students will respond to certain types of

art, what language they will use at certain ages and levels of readiness, how

their previous artistic background and their aesthetic tastes will influence

responses, and how personality types and learning styles relate to art inter-

pretations.

It is a major thesis of this paper that the bases of art criticism need to be

developed and expanded. This author believes that first and foremost art

criticism should be considered as an educational procedure that results in skills

for exploring aesthetic, sociological, personal, symbolic, and thematic mean-

ings of art. Rather than so constraining the art critical procedures within the

brackets of aesthetic integrity that they fail to have relevance to the student,

foundational rationales need to be developed beyond philosophic aesthetics to

a sociological aesthetic, and linkages need to be found to various types of

models for the very pragmatic purposes of facilitating classroom implementa-

tion.

Linguistic Development

Although Ecker (1967, 1972) has suggested that ultimately art critical

judgments occur through internalized responses to art, for practical and

pedagogical purposes, art criticism is a linguistic act entailing some form of

description, analysis, interpretation, and, often, judgment1 of an art object.

According to Feldman (1973), art criticism is "more or less informed, and

more or less organized, talk about art" (p. 50).

Despite language being the means through which art criticism is ex-

pressed, comparatively very little work has been done on children's re-

sponses to art. David Ecker, David Perkins, Ralph Smith and Brent Wil-

son have to some extent started to categorize the student's verbal re-

sponses to an art object or event, but any developmental schema for ver-

bal response to the work is still forthcoming. (Madeja, 1979, pp. 31-32).

Descriptions and collections of children's verbal responses to art do now exist

in the literature, but patterns of development have not been established nor

have such responses often been related specifically to art criticism (Kordich,

1982). A study by Winner, Rosenstiel, and Gardner (1976) indicates that

linguistic metaphors are developed along an age-based progression from the

'In this paper, these four steps serve as a generalized frame of reference.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ART CRITICISM INSTRUCTION 165

spontaneous generation of metaphors to an ability to explain metaphoric

meanings. This progression also exhibits an initial dependence on visual

similaritiesand later an abilityto form more abstractrelationships.In a study

of one preprimarychild, it was found that metaphorswere used in pretend

play duringage 2; by age4 metaphorswerebasedon perceptualqualities(Win-

ner, 1979). The use of metaphorsat these early ages appearsto be limitedto

functional and perceptual similarities. Not until the ages of 8 to 10 are

linguistic metaphors understood to describe psychological states, i.e., an

unkindperson as being icy, or used in a cross-sensorymanner,i.e., loud col-

ors. Significant to educators in the visual arts is the finding that when

presentedin the context of a picturedepictingthe linguisticmetaphor,early

primarychildrenare able to make correctselections. "The capacityto com-

prehendpsychologicalmetaphorsis a function of the measureused to assess

comprehension"(Winner,Wapner,Cicone, & Gardner,1979, p. 72). Not un-

til the middle years of childhood, however, do childrenspontaneouslynotice

expressive properties in works of art, and they do not talk about such

characteristicswithout promptinguntil early adolescence.This finding is of

significanceto art criticismin that "readingexpressionis essentialif a picture

is to be apprehendedin an aestheticmode" (Winner, 1982, p. 110).

Other findingssuggestthat a sensitivityto compositionis not evidentuntil

the middleelementaryyearsalthough6-year-oldscan classifyworksby style if

the distractionof conflicting subject matter is removed. Preferencesin 4-to

8-year-old children are based on color, representationalcontent, or both.

Judgments are based on whether or not they like the art work. Realism

becomes a determiningfactor of preferencefrom approximatelyage 8 until

adolescence,with judgmentsat these ages referredto experts.In adolescence,

a variety of styles is accepted, and aesthetic judgments become relative to

personaltaste or the artist'sintent. Accordingto Winner(1982),these changes

in preferenceand judgment parallelsimilar changes evidencedin cognitive,

personality,and moral development.

Parson, Johnston, and Durham(1978)have studiedthe developmentof ar-

tistic responsesdistinctfrom the more familiarstagesof logical-mathematical

or moral frameworks.Responsesto the topics of representation,subjectmat-

ter, feelings, artisticintent, color, and evaluationreveala developmentalsen-

sitivitytowardperceptualaspectsrelevantto the aestheticexperience.For ex-

ample, initially color in a painting is judged on the basis of personal

preference;in the secondstage, its realisticapplication;and in the thirdstage,

its expressiveaspects.

Despite these and other studies, there is, however, no widely accepted

developmental linguistic framework analogous to the familiar steps of

children'sgraphicexpressions.An often-statedpurposeof art criticismis to

wean childrenaway from literaland subjectiveresponsestowarda perception

of qualitiesintegralto the art object's physicalbeing. Thereis no formalized

linguistic framework that would indicate transitions along that route. In

developingart curriculafor elementarygrades,Chapman(1985)found ample

informationon "grade-by-gradeplacementof art conceptsand skillstypically

introducedthroughstudio work" (p. 207). For the sequencingof responsesto

art, she had to rely on teachingexperience,theoreticalwork, and the objec-

tives developed in other subject areas such as science, mathematics,social

studies, and languagearts.

The implementationof art criticisminstructionshould not be dependent

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

166 KAREN A. HAMBLEN

upon the existence of a linguistic developmental model. The inconsistencies,

errors, and problems that have come from relying on a model of children's

graphic expressions developing through a series of linear, age-referenced steps

is well-documented (Pariser, 1983; Wilson & Wilson, 1982). The lessons

learned from that experience need to be heeded. A general frame of reference

would be helpful, however.

Formalized talk about art, in addition to indicating what is perceived, re-

quires such conceptual skills as ordering, sequencing, and differentiating, as

well as the possession of language skills that allows for the written or verbal ex-

pression of those concepts. Just as a child's graphic expression is often not

congruent with what a child knows or is able to see, it is important to keep in

mind that what a child verbalizes in regard to art may lag far behind what is ac-

tually perceived and conceptually understood.

Developmental Model Parallels

Human development studies have been primarily linked with art produc-

tion, and artistic development has been used almost exclusively to mean ar-

tistic expression. In regard to art criticism, developmental theories have

primarily found application to the actual format and character of the art

criticism procedure itself rather than to age-based developmental patterns of

art critical response. The art critical levels of description, analysis, interpreta-

tion, and judgment are often considered to be developmental, paralleling, for

example, the cognitive stages of Piaget (Kordich, 1982), the steps of perceptual

models such as those of Arnheim (1969) and Bruner (1958), and the hier-

archical categories of learning models such as those of Bloom and Gagne (Arm-

strong & Armstrong, 1977; Hamblen, 1984). These developmental and hier-

archical models have in common the movement from lower levels of undifferen-

tiated, spontaneous, and concrete ways of responding toward higher levels of

differentiated, abstract, and internally constructed interpretations of reality.

The art criticism format serves as a miniature model of conceptual, perceptual,

and learning skill development. Movement through an art criticism format is

discussed as both an instructional procedure and as a developmental pattern

that occurs over time.

Ascertaining conceptual and structural similarities between cognitive stages

and art critical formats provides a valuable theoretical foundation for art

criticism in terms of empirical studies and actual classroom applications. Kor-

dich (1982) tested the cognitive levels of children and found that achievement

in art critical levels was commensurate with the attainment of parallel

cognitive levels. It was not that younger children could not act within the

higher levels of art criticism, but rather that they responded in less detail, ex-

pressed fewer discriminations, and clung to interpretations based on literal

qualities. Most developmental studies have neither a direct art criticism in-

structional application nor are conducted, as in the Kordich example,

specifically in relationship to art criticism instruction.

Perceptual Development

The perceptual foundations of art criticism follow essentially the same pat-

tern as that of relationships made to theories of conceptual development and

learning. Madeja (1979) finds Arnheim's (1969) categories of perception to be

helpful in explaining the perceptual process entailed in art criticism, i.e.,

observation, description, selection, and generalization. In addition to referen-

cing the steps of the art critical process to aesthetic theories, i.e., description-

imitationalism, analysis-formalism, interpretation-expressionism, Mittler

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ART CRITICISM INSTRUCTION 167

(1976) bases much of his art critical rationale on Bruner's (1958) four stages of

discriminate perceptual decision-making. This perceptual process is initiated

by a cursory primitive scanning, proceeds to a seeking of relevant cues, is

followed by the formation of a tentative categorization, and concludes with a

confirmation that results in a final categorization. As in art criticism, Bruner's

perceptual process involves a progression away from merely subjective, cur-

sory responses to greater discriminatory powers that result in a judgment

based on evidence that has been examined. The art criticism process is a

distillation and a consciously heightened perceptual experience of what occurs

on an often preconscious level throughout one's everyday perceptions.

Sociological Relationships

With aesthetics forming the most pervasive foundational area of art

criticism theory and practice, it is not surprising that sociological relationships

in the art critical process, the social significance of art objects studied, and

students' socio-economic background have received short shrift in the

literature. With little work done on the more traditional dimensions of in-

dividual differences as these relate to art critical responses, sociological im-

plications essentially are ignored. The overarching goal for art criticism in-

struction appears to be to wean students away from responses rooted in their

life world.

Sociology of the Art Critical Process

Art criticism, as a formalized procedure, is a learned skill; it is not how one

normally responds to art. It, thereby, represents a particular class of responses

to art not experienced by all citizens. The specialized language skills acquired

through art critical instruction enables one to communicate meanings specific

to art that can be shared with others similarly schooled.

Based on the socio-economic theory of Gouldner (1979), who has examined

the social implications of speech community membership, Hamblen (1984) has

termed the specialized linguistic codes of art criticism as constituting the

Culture of Aesthetic Discourse (CAD). Hamblen questions whether participa-

tion in the CAD might not unduly separate students' responses to art from

their biographical life worlds. In a similar vein, Nadaner (1985) questions the

formalist approach that is "commonly used in art classes, . . . restricts itself

to formal relations in the work and de-emphasizes the content of the work and

its socially-constructed meaning" (p. 11). Nadaner (1984, 1985) presents a

strong case for including social and subjectively constructed meanings in art

criticism. He advocates two types of criticism: historical criticism which "at-

tends to the 'world views' of the observer at a specific moment in history under

specific social conditions, [and] semiotic criticism [which] attends to the

'cultural codes' used by observers to understand signs in a visual work" (1985,

p. 11). Others have also lamented the general emphasis on formalistic

aesthetics throughout the art curriculum and have proposed inclusion of

sociological content (Bersson, 1982). There is a lack of prescribed, easily

replicated teaching strategies that would facilitate the implementation of

socially relevant art criticism.

Social Benefits of Art Criticism Study

Art criticism proponents have been fond of extolling the virtues of art

critical study, ranging from the intrinsic value of art study to statements on the

social benefits of an aesthetically enlightened populace, with all shades of

cognitive development and aesthetic literacy benefits in between. Similar to the

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168 KAREN A. HAMBLEN

many benefits imputed to art production, it is often assumed that art criticism

study itself will result in social improvement rather than the process specifical-

ly being concerned with social meanings or the object of study necessarily em-

bodying social content. It has been proposed that art criticism will result in an

enlightened populace which has an expanded repertoire of feeling (Broudy,

1972; Smith, 1967) and that art critical skills may develop a type of visual

literacy that will counter the invidious effects of the mass media (Feldman,

1973). Broudy (1972), Johansen (1982), and Smith (1967) believe that ex-

emplars of art should constitute the objects of art critical study; Feldman

(1973) proposes that all types of humanmade objects be studied, "the meaning

of clothing, furniture, domestic architecture, and product design" (p. 55). The

critical act, according to Feldman, completes the aesthetic experience by

socializing it, by making it public. It should be noted that these same gen-

eralized social benefits have, at various times, been attributed to the art pro-

duction process, too.

As elsewhere in the art curriculum, questions on the appropriateness of in-

cluding social dimensions in the art study process will, in all probability, con-

tinue to be debated. However, as long as aesthetic theory forms the primary

foundation of art criticism instruction, with commensurate goals of

eliminating subjective responses and of developing sophisticated aesthetic

linguistic codes, it is doubtful that sociological implications will make any ma-

jor inroads.

Cognitive Learning Styles and Personality Types

Art criticism is in its infancy with regard to the psychology of the learner.

Other than the most general of comments, such as that the assumptive world

of students should be taken into consideration, few concessions and

allowances are made for the individual student in terms of learning styles and

personality types. There are few studies that look at art criticism in terms of

student differences. In a noteworthy exception, Hollingsworth (1983) tested

whether a counterattitudinal approach, habituation and/or art criticism were

efficacious ways in which to increase preferences of students of different grade

levels. It was found that for elementary students art criticism was most effec-

tive. A combination treatment was best for junior high, and a counterat-

titudinal approach might be useful to bring about a specific change in regard

to a particular work.

Lovano-Kerr (1983) relates art criticism methodologies and aesthetic percep-

tion to cognitive style.

The various approaches to art criticism and aesthetic perception may be

favoring one mode of processing information over the other. The em-

phasis of parts to the whole, restructuring, and hypotheses-testing may

exclude persons with a global style (field-dependent). Conversely, ap-

proaches focusing on mood, feeling, and intuition may exclude persons

with a more articulated style (field-independent). A better understanding

of these influences in responding to art could be basic to instructional

development, teaching, and learning. (p. 202)

In a study of museum tours, Housen (1980) found that visitors could be

classified into five types, ranging from the naive to the knowledgeable. Not

only could types of responses be correlated with level of sophistication, but

tour methodologies could also be prescribed. For example, those visitors with

a subjective or utilitarian focus on the object benefit from an exploratory, par-

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ART CRITICISM INSTRUCTION 169

ticipatory tour. Those visitors concerned with categorical placement and

knowledge about the artist, style, and period preferred a lecture mode.

In providing a general art education text, Chapman (1978) does not endorse

any one art critical procedure, but, rather, presents the steps and applications

of four different methods: inductive, deductive, interactive, and empathic.

These are discussed in terms of the art critical outcomes that result from using

these different approaches, not how certain types of students might be com-

patible with certain types of approaches. There are admonitions in art educa-

tion literature against believing that art critical judgments are either final or

definitive, or that students should be required to conform to any standards

during analysis and interpretation other than referential adequacy (Broudy,

1972; Smith 1967). But, as Lanier (1985) notes, the focus of art criticism is

foremost on the art object, not the perceiver of the object. Mittler (1982), in

addition to finding parallels between art theories and the steps of art criticism,

proposes that different theories be selected to guide the art critical process

depending upon the character of the object being analyzed. Art theories and

art critical approaches are selected as to their applicability to the art object

under consideration, not how the student might best be able to relate to the ob-

ject on the basis of his/her learning style or personality type.

Art criticism is not an exercise in self-expression as art production has often

been; yet, student factors such as age, experience, and background will have

an impact on the art critical learning that takes place. How those personal and

learning factors relate to the linguistic, conceptual, and perceptual complex of

processes that make up art criticism remain essentially unexplored. Studies on

individual differences from a variety of areas will need to be culled for relevant

findings and put within the art criticism perspective.

Teaching Methodologies

Instructional Cues

Examples of student-teacher dialogues abound in the literature and make

for interesting reading, but they provide few practical cues for actual im-

plementation. Feldman (1973) mentions the Socratic questioning method, yet

whether a teacher could implement this methodology from Feldman's book is

doubtful. Some authors present fairly precise and clearly outlined procedural

formats (Feinstein, 1983; Lankford, 1984), and others have presented infor-

mation on how classroom questions can be generated (Armstrong & Arm-

strong, 1977; Hamblen, 1984; Taunton, 1983).

There are numerous studies throughout the literature that have implications

for art criticism instruction. For example, as mentioned earlier, many studies

indicate that young children classify and make preference judgments about art

on the basis of subject matter, while older children tend to be able to differen-

tiate according to style. Questioning these broad generalizations, Hardiman and

Zernich (1977) suggested that a work's degree of realism may be a determining

factor for preference at all grade levels. Findings from other studies suggest

that the perception of aesthetic qualities may require a knowledge of artistic

conventions, the learning of stylistic rules, and an awareness of artistic inten-

tions (D'Onofrio & Nodine, 1981; Rush & Sabers, 1981). Perceptual studies re-

quiring art-based qualitative responses may also provide information on

linguistic patterns relevant to art criticism (Evans, 1984). Application of data

from such studies will, of course, require careful attention to the qualifying

variables of respondents' ages, personality types, cognitive styles, and past ar-

tistic experiences.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

170 KAREN A. HAMBLEN

Learning Theory

Authors have not overlooked similarities among the traditional art criticism

four-step format, hierarchies of learning, and instructional taxonomies. These

relationships are particularly valuable in that they not only furnish a

theoretical foundation for art criticism but also provide clues for classroom

implementation. Hamblen (1984) has developed an art criticism questioning

strategy within the framework of Bloom's taxonomy, with further similarities

noted to the models of Gagne, Guilford, Harrow, Krathwohl, and Piaget.

Armstrong and Armstrong (1977) refer to Gagne's hierarchy of learning, Par-

sons' analysis of teachers' questions, and Ausubel's use of advanced

organizers to generate questions toward increasingly higher cognitive levels;

Taunton (1984) finds Gallagher and Aschner's categories helpful for shaping

questions to be used in art dialogues. Learning hierarchies not only provide an

instructional format but also indicate the patterned progression through

which, it is often believed, learners progress over a period of time.

Format Validity

An art criticism format is the outward, formal manifestation of its author's

goals and perspectives and is indicative of a particular philosophical or foun-

dational perspective. With reference to the steps involved in the scientific

method, Clements (1979) proposes an inductive art criticism methodology con-

sisting of engaging in analysis, forming an hypothesis, and confirming the

hypothesis. In a different manner, Lankford (1984) advocates a

phenomenological approach and includes three preliminary steps to prepare

the student for the art criticism experience. The steps of receptiveness, orien-

ting, and bracketing are followed by interpretative analysis and synthesis.

Art criticism derives not only its formal characteristics but, concomitantly,

its foundational rationale through the adaptation of a particular type of pro-

cedure. Although an art criticism format's formal qualities should not be con-

sidered equivalent to its substance, a particular procedure often has

antecedents in foundational areas. The art criticism process itself might

replicate conceptual development, modes of perception, learning procedures,

and patterns of awareness in the aesthetic experience. Such linkages suggest

theoretical validity as well as form the framework for further inquiry and pro-

vide clues for instructional implementation. As an art content area, art

criticism has the distinction of having a procedural format integral to its being

and a format explanatory of some type of human activity.

A note of caution against an uncritical enthusiasm for this type of format

validity is in order. Similarities between an art criticism format and a learning

hierarchy may merely indicate a pedagogical compatibility that can be pro-

fitably combined in an educational system in which there is a familiarity with,

and receptivity to, hierarchical constructs. This author believes that the art

criticism process should be about educational outcomes and artistic meanings

rather than about how one believes human inquiry and behavior, on a pan-

social and panindividual level, are organized. In proposing art criticism for-

mats that have overarching implications, as does, for example, the inductive

scientific approach, a truth may be implied above and beyond the analysis of

such and such art objects.

Art criticism certainly can be enlightening and even provide the thrills that

accompany expanded consciousness, yet art criticism is not a quest for eternal

verities. Assumptions of format validity can easily obscure the need for multi-

ple art critical approaches, differences students exhibit in their responses to

art, how students process information, and how they proceed to understand

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ART CRITICISM INSTRUCTION 171

any phenomenon, art included. Essentially, art criticism involves organizing

responses to, and ideas about, art. How those responses and ideas are or-

ganized in an art criticism format is a matter of choice indicative of values

placed on how it is believed students might best perceive and understand art.

An art criticism format is merely a curriculum option rather than an exclusive-

ly correct view on art.

Recommendations

Studio instruction is supported by a less than perfectly organized and

coherent pattern of inquiry (Rush, 1984). Nonetheless, artistic expression has a

respectable record of theory and research in foundational areas that provides

clues for actual classroom application. The proponents of art criticism need to

look beyond their philosophical-aesthetic horizons to establish a more firm

and varied empirical and theoretical foundation. Efforts need to be made to

establish a foundation for art criticism based on psychological studies, learn-

ing theory, perceptual theory, sociology, and cross-cultural aesthetics. An in-

itial, basic model of the psychological foundations of art criticism will need to

incorporate findings in the four areas of language development, conceptual

development, perceptual theory, and learning theory. Information in these

four areas will need to be assessed in terms of development over time as well as

in terms of responses within an art criticism format procedure at a given time.

As has been done with graphic expression, a series of vertical and longitudinal

studies need to be conducted wherein art-related comments made by

preprimary children and children of other ages are collected and analyzed for

their semantic content.

Parallels among art criticism formats, learning taxonomies, and

developmental models need to be investigated beyond the theoretical realm

and obvious conceptual similarities. Primary research in art criticism will need

to be heavily supplemented by data from relevant studies carried out in

linguistics, developmental psychology, experimental aesthetics, learning

theory, and perceptual investigations. Primarily, the many art criticism for-

mats now available will need to be thoroughly catalogued and evaluated as to

their applicability to specific contexts, goals, and student readiness levels

(Hamblen, 1985). As Geahigan (1980) notes in regard to art critical methods

and goals, "It is significant that questions such as these have yet to be asked in

the literature. Instead, the literature has grown in an incremental manner by

writers simply adding to the body of existing method and goal prescriptions"

(p. 64).

Conclusions

The general state of art criticism as it appears in the literature is one of dif-

fused aesthetic foundations and psychological foundational rationales built on

model-format similarities. There are vague allusions to individual differences,

an indifference to sociological foundations, and few explicit cues for

classroom implementation. These theoretical and research deficits are com-

pounded by the educational milieu art criticism instruction must enter. Artistic

production has served as not only the cornerstone of art education since its in-

ception, but has constituted, for all practical purposes, the entire edifice.

There are no periodicals devoted to art criticism lessons and projects, no full-

color advertisements displaying instructional procedures and the written

results of students' art criticism efforts, and no scholarships given for the most

insightful art critical analysis produced by a high school student.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

172 KAREN A. HAMBLEN

There are some fairly positive prospects for art criticism that might counter-

balance the bleak state of current foundational and research development.

Whereas a decade or so ago Smith (1973) noted a climate unfavorable to art

criticism due to its intellectualized approach, Grieder (1985) now believes that

"a form of education that is opposed to the intellect is sure to meet opposition

or neglect" (p. 7). Art criticism has the potential for being the most clear-cut

instructional area in the aesthetic education model. No other area has an in-

structional format integral to its very being.

References

Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual thinking. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Armstrong, C.L., & Armstrong, N.A. (1977). Art teacher questioning strategy. Studies in Art

Education, 18 (3), 53-64.

Bersson, R. (1982). Against feeling: Aesthetic experience in technocratic society. Art Education,

35 (4), 34-39.

Broudy, H.S. (1972). Enlightened cherishing: An essay on aesthetic education. Urbana. IL:

University of Illinois Press.

Bruner, J.S. (1958). On perceptual readiness. In D.C. Beardslee & M. Wertheimer, (Eds.),

Readings in perception. Princeton, N.J.: D. Van Nostrand.

Chapman, L.H. (1978). Approaches to art in education. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Chapman, L.H. (1985). Curriculum development as process and product. Studies in Art Educa-

tion, 26 (4), 206-211.

Clements, R.D. (1979). The inductive method of teaching visual art criticism. Journal of

Aesthetic Education. 13 (3), 67-78.

D'Onofrio, A., & Nodine, C.F. (1981). Children's responses to paintings. Studies in Art Educa-

tion, 23 (1), 14-23.

Ecker, D.W. (1967). Justifying aesthetic judgment. Art Education, 20, 5-8.

Ecker, D.W. (1972). Teaching art criticism as aesthetic inquiry. New York University Education

Quarterly, 3 (4), 20-26.

Evans, E.D. (1984). Children's aesthetics. Current topics in early childhood education, Vol. V.

Lilian G. Katz, Ed. Norwood, NJ: Abex.

Feinstein, H. (1983). The therapeutic trap in metaphoric interpretation. Art Education, 36 (4),

30-33.

Feldman, E. (1973). The teacher as model critic. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 7(1), 50-57.

Geahigan, G. (1975). Feldman on evaluation. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 9 (4), 29-42.

Geahigan, G. (1980). Metacritical inquiry in arts education. Studies in Art Education, 21 (3),

54-67.

Gouldner, A.W. (1979). The future of intellectuals and the rise of the new class. New York:

Seabury.

Grieder, T. (1985). A post-modern theory of art education. Art Education, 37(1), 6-8.

Hamblen, K.A. (1984). An art criticism questioning strategy within the framework of Bloom's

taxonomy. Studies in Art Education, 26 (1), 41-50.

Hamblen, K.A. (1985). A descriptive and analytical study of art criticism formats with implica-

tions for curricular implementation. American Educational Research Association Arts and

Learning SIG Proceedings, 1-14.

Hamblen, K.A. (in press) Exploring contested concepts for aesthetic literacy. Journal of Aesthetic

Education.

Hardiman, G.W., & Zernich, T. (1977). Influence of style and subject matter on the development

of children's art preferences. Studies in Art Education, 19 (1), 29-35.

Hollingsworth, P.C. (1983). The combined effect of mere exposure, counterattitudinal advocacy,

and art criticism methodology on upper elementary and junior high students' affect toward

art works. Studies in Art Education, 24 (2), 101-110.

Housen, A. (1980). What is beyond, or before, the lecture tour? A study of aesthetic modes of

understanding. Art Education, 33 (1), 16-18.

Johansen, P. (1982). Teaching aesthetic discerning through dialog. Studies in Art Education, 23

(2), 6-13.

Kordich, D.D. (1982). An instructional strategy in art criticism for the middle school: A game

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ART CRITICISM INSTRUCTION 173

approach focusing on the stages of analysis (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, 1982),

Dissertation Abstracts International, 43, 1016A.

Lanier, V. (1985). Discipline-based art education: Three issues. Studies in Art Education, 26

(4), 253-256.

Lankford, E.L. (1984). A phenomenological methodology for art criticism. Studies in Art Educa-

tion, 25 (3), 151-158.

Lovano-Kerr, J. (1983). Cognitive style revisited: Implications for research in art production and

art criticism. Studies in Art Education, 24 (3), 195-205.

Madeja, S. (1979). The child and aesthetic development. The arts and handicapped people:

Defining the national direction. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Education for the Handicapped,

Division of Innovation and Development, National Committee, Arts for the Handicapped.

(ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 158 445)

Mittler, G.A. (1976). Perceptual thoroughness as a prelude to discriminate decision making in art.

Viewpoints: Bulletin of the School of Education at Indiana University, 52 (3), f5-29.

Mittler, G.A. (1980). Learning to look/looking to learn: A proposed approach to art appreciation

at the secondary school level. Art Education, 33 (3), 17-21.

Mittler, G.A. (1982). Teaching art appreciation in the high school. School Arts, 82 (3), 36-41.

Nadaner, D. (1984). Critique and intervention: Implications of social theory for art education.

Studies in Art Education, 26 (1), 20-26.

Nadaner, D. (1985). Responding to the image world: A proposal for art curricula. Art Education,

37 (1), 9-12.

Parsons, M., Johnston, M., & Durham, R. (1978). Developmental stages in children's aesthetic

respohses. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 12 (1), 83-104.

Pariser, D. (1983). The pitfalls of progress: A review and discussion of Gablik's Progress in art.

Visual Arts Research, 9 (1), 41-54.

Rush, J.C. (1984). Does anyone read Studies any more? Studies in Art Education, 25 (3),

139-140.

Rush, J.C., & Sabers, D.L. (1981). The perception of artistic style. Studies in Art Education, 23

(1), 24-32.

Smith, R. (1967). An exemplar approach to aesthetic education. Bureau of Educational Research,

Project No. 6-3-6-06127-1609, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Office of Education and Department of

Health, Education and Welfare.

Smith, R. (1973). Teaching aesthetic criticism in the schools. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 7

(1), 38-49.

Taunton, M. (1983). Questioning strategies to encourage young children to talk about art. Art

Education, 36 (4), 40-43.

Taunton, M. (1984). Reflective dialogue in the art classroom: Focusing on the art process. Art

Education, 37 (1), 15-16.

Weitz, M. (1962). The role of theory in aesthetics. In J. Margolis, (Ed.), Philosophy looks at the

arts: Contemporary readings in aesthetics. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Wilson, B.G., & Wilson, M. (1982). The persistence of the perpendicular principle: Why, when

and where innate factors determine the nature of drawings. Visual Art Research, 15 1-18.

Winner, E. (1979). New names for old things: The emergence of metaphoric language. The

Journal of Child Language, 12 (4), 289-297.

Winner, E. (1982). Invented worlds: The psychology of the arts. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press.

Winner, E., Rosenstiel, A., & Gardner, H. (1976). The development of metaphoric understand-

ing. Developmental Psychology, 12, 289-297.

Winner, E., Wapner, W., Cicone, M., & Gardner, H. (1979). Measures of metaphor. In E. Win-

ner and H. Gardner (Eds.), New directions for child development: Fact, fiction, and fantasy in

childhood. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

This content downloaded from 193.227.1.43 on Fri, 20 Sep 2013 05:24:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

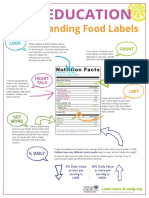

- Nutrition LabelДокумент2 страницыNutrition LabelemysamehОценок пока нет

- Label ReadingДокумент4 страницыLabel ReadingemysamehОценок пока нет

- Understanding Food and CN LabelsДокумент2 страницыUnderstanding Food and CN LabelsemysamehОценок пока нет

- Nutrition BookДокумент5 страницNutrition Bookemysameh100% (1)

- Engagement Inventory Teacher RecordДокумент1 страницаEngagement Inventory Teacher Recordapi-369324244Оценок пока нет

- Norman Holland Willing Suspension of DisbeliefДокумент12 страницNorman Holland Willing Suspension of DisbeliefemysamehОценок пока нет

- Authorizing Readers Resistance and Respect in Teaching Literary Reading ComprehensionДокумент2 страницыAuthorizing Readers Resistance and Respect in Teaching Literary Reading ComprehensionemysamehОценок пока нет

- Vocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 10 Test AДокумент4 страницыVocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 10 Test Aemysameh100% (2)

- Vocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test AДокумент5 страницVocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test Aemysameh100% (5)

- Revision Exercises Relative ClausesДокумент3 страницыRevision Exercises Relative ClausesemysamehОценок пока нет

- Language TeachingДокумент9 страницLanguage TeachingemysamehОценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Narrative and EngagementДокумент54 страницыRelationship Between Narrative and EngagementemysamehОценок пока нет

- Vocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test BДокумент5 страницVocabulary & Grammar Test Unit 9 Test Bemysameh50% (4)

- Cumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test AДокумент5 страницCumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test AemysamehОценок пока нет

- Cumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test BДокумент5 страницCumulative Skills Test Units 1-5 Test BemysamehОценок пока нет

- Passivity and MotivationДокумент10 страницPassivity and MotivationemysamehОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Pta CtdisrДокумент62 страницыPta CtdisrMuhammad HasnainОценок пока нет

- Fundamentals of Pharmacology 9Th Edition Bullock Full ChapterДокумент51 страницаFundamentals of Pharmacology 9Th Edition Bullock Full Chapterbetty.tavares510100% (11)

- Presentation Skills GESTДокумент10 страницPresentation Skills GESTLamin KamaraОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan 8 SementaraДокумент43 страницыLesson Plan 8 SementaratengttongtungОценок пока нет

- English 5 - Q1 - W1 - 2023-2024Документ8 страницEnglish 5 - Q1 - W1 - 2023-2024Chiara Margarita Dogos RosaОценок пока нет

- Universal Law of Success - by Brian Tracy - Doc 1-11 9/4/2008Документ11 страницUniversal Law of Success - by Brian Tracy - Doc 1-11 9/4/2008Sahadevan Nair100% (4)

- Positioning Yourself Through Effective Communication and Public SpeakingДокумент32 страницыPositioning Yourself Through Effective Communication and Public SpeakingElizabeth MlelwaОценок пока нет

- About DPSA Personality StylesДокумент13 страницAbout DPSA Personality Stylesgenebaba100% (1)

- This Is Hybrid - Texts - ArchitectureДокумент38 страницThis Is Hybrid - Texts - ArchitectureivicanikolicОценок пока нет

- Unit 5 Topic 1 Developing and Delivering An Informative SpeechДокумент6 страницUnit 5 Topic 1 Developing and Delivering An Informative SpeechNoraima100% (1)

- Consumer Psychology Review - 2020 - Schwarz - Metacognitive Experiences As Information Processing Fluency in ConsumerДокумент22 страницыConsumer Psychology Review - 2020 - Schwarz - Metacognitive Experiences As Information Processing Fluency in ConsumerXmai LeeОценок пока нет

- Group 4 Royal JetДокумент20 страницGroup 4 Royal JetPatrick MaliksiОценок пока нет

- Semantic NetworkДокумент60 страницSemantic NetworkAsif AliОценок пока нет

- ISO 27001 2013 Statement of ApplicabilityДокумент21 страницаISO 27001 2013 Statement of Applicabilitymrehan2k2Оценок пока нет

- Theory of Information ScienceДокумент45 страницTheory of Information ScienceriteshyuvarajОценок пока нет

- Bellinger and DeCaro (2019) Note-Taking Format and Difficulty Impact Learning From Instructor-Provided Lecture NotesДокумент13 страницBellinger and DeCaro (2019) Note-Taking Format and Difficulty Impact Learning From Instructor-Provided Lecture NotesSergio Andrés Quintero MedinaОценок пока нет

- KSSMPK Scheme of Work English For Communication Form 5 Special Education Week Theme Learning Standard Listening and Speaking Reading WritingДокумент4 страницыKSSMPK Scheme of Work English For Communication Form 5 Special Education Week Theme Learning Standard Listening and Speaking Reading Writingmahesi magenОценок пока нет

- Situated Algorithms: A Sociotechnical Systemic Approach To BiasДокумент18 страницSituated Algorithms: A Sociotechnical Systemic Approach To BiasPremОценок пока нет

- Types of BuildingsДокумент13 страницTypes of BuildingsChilupuri Sreeya100% (1)

- Literature Review Interpersonal SkillsДокумент7 страницLiterature Review Interpersonal Skillsea8r2tyk100% (1)

- Dlp-English 8 - March 02, 2023Документ8 страницDlp-English 8 - March 02, 2023Kerwin Santiago ZamoraОценок пока нет

- Cyclone Nivar, November 2020: Analysis and MapsДокумент3 страницыCyclone Nivar, November 2020: Analysis and Mapsm_sachuОценок пока нет

- Udlg Graphicorganizer v2-2 Numbers-YesДокумент1 страницаUdlg Graphicorganizer v2-2 Numbers-YesIGNACIO MOREIRAОценок пока нет

- Evaluating A Framework For Information Management in E-Agriculture Using Expert OpinionДокумент8 страницEvaluating A Framework For Information Management in E-Agriculture Using Expert OpinionInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Daily Irradiance Data: PVGIS-5 Geo-Temporal Irradiation DatabaseДокумент1 страницаDaily Irradiance Data: PVGIS-5 Geo-Temporal Irradiation DatabaseIon PleșcaОценок пока нет

- BattlespaceAwareness PDFДокумент17 страницBattlespaceAwareness PDFYesika RamirezОценок пока нет

- Marketing Management MCQsДокумент133 страницыMarketing Management MCQsHuy Ha HoangОценок пока нет

- DSS SummaryДокумент47 страницDSS SummarywanderaОценок пока нет

- Quality Assurance & School-Based Support Division Education Bureau 2016Документ14 страницQuality Assurance & School-Based Support Division Education Bureau 2016Sobia AliОценок пока нет

- As 2609.1-2005 Methods For Assessing Modifications To The Flavour of Foodstuffs Due To Packaging Sensory AnalДокумент10 страницAs 2609.1-2005 Methods For Assessing Modifications To The Flavour of Foodstuffs Due To Packaging Sensory AnalSAI Global - APACОценок пока нет